Jacques Necker

Jacques Necker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chief Minister of the French Monarch | |

| In office 29 July 1789 – 3 September 1790 | |

| Monarch | Louis XVI |

| Preceded by | Baron of Breteuil |

| Succeeded by | Count of Montmorin |

| In office 25 August 1788 – 11 July 1789 | |

| Monarch | Louis XVI |

| Preceded by | Archbishop de Brienne |

| Succeeded by | Baron of Breteuil |

| Controller-General of Finances | |

| In office 25 August 1788 – 11 July 1789 | |

| Monarch | Louis XVI |

| Preceded by | Charles Alexandre de Calonne |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Foullon de Doué |

| Director-General of the Royal Treasury | |

| In office 29 June 1777 – 19 May 1781 | |

| Monarch | Louis XVI |

| Preceded by | Louis Gabriel Taboureau des Réaux |

| Succeeded by | Jean-François Joly de Fleury |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 30 September 1732 Geneva,[1] Republic of Geneva |

| Died | 9 April 1804 (aged 71) Geneva, Léman (department), France |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Germaine |

Jacques Necker (IPA: [ʒak nɛkɛʁ]; 30 September 1732 – 9 April 1804) was a banker of Genevan origin who became a finance minister for Louis XVI and a French statesman. Necker played a key role in French history before and during the first period of the French Revolution.[2]

Necker held the finance post between 1777 and 1781 and "is remembered today for taking the unprecedented step in 1781 of making public the country’s budget, a novelty in an absolute monarchy where the state of finances had always been kept a secret."[3] Necker was dismissed within a few months. By 1788 the inexorable compounding of interest on the national debt brought France to a fiscal crisis.[4] Necker was recalled to royal service. When he was dismissed on 11 July 1789, it was a factor in causing the Storming of the Bastille. Within two days Necker was recalled by the king and the assembly. Necker entered France in triumph and tried to accelerate the tax reform process. Faced with the opposition of the Constituent Assembly he resigned in September 1790 to a reaction of general indifference.

Necker was a constitutional monarchist, a political economist, and a moralist, who wrote a severe critique of the new principle of equality before the law. Necker fully embraced the label of moderate and the concept of the golden mean.[5]

Early life

Necker was born in Geneva in a Calvinist household. In 1747 Jacques became a clerk in the bank of Thellusson and Vernet. In 1750 he was sent to Paris and worked for the bank Girardot. Soon after he managed to learn Dutch and English. On one day, he replaced the first clerk in charge of trading on the stock exchange and through a sequence of trades, he made a quick profit of half a million.[6] In 1762, Vernet retired and Necker became a partner in the bank with Peter Thellusson who managed the bank in London, while Necker served as his managing partner in Paris. In 1763, before the end of the Seven Years' War, he successfully speculated in British debentures or bonds, wheat, and possibly Canadian shares, which he sold at a good profit in the next few years.[7]

Necker had fallen in love with Madame de Verménou, the widow of a French officer. When she went to see Théodore Tronchin, she became acquainted with Suzanne Curchod. In 1764, Madame de Verménou brought Suzanne to Paris as a companion for Thelusson's children. Suzanne was engaged to British writer Edward Gibbon, but he was forced to break the engagement. Necker transferred his love from the wealthy widow to the ambitious Swiss governess. They married before the end of the year. In 1766, they moved to Rue de Cléry and had a daughter, Anne Louise Germaine, later the famed author and salonnière Madame de Staël.

Madame Necker encouraged her husband to try to find himself a public position. He accordingly became a syndic (or director) of the French East India Company, around which a fierce political debate revolved in the 1760s between the company's directors and shareholders and the royal ministry over its administration and the company's autonomy.[8] "The ministry, concerned about the financial stability of the company, employed the Abbé Morellet to shift the debate from the rights of the shareholders to the advantages of commercial liberty over the company's privileged trading monopoly."[9] After showing his financial ability in its management, Necker defended the company's autonomy in an able memoir against the attacks of Morellet in 1769.[10] As the company never made any profit during its existence, the monopoly ended.[11] The era of free trade had begun.[12] Necker bought up the company's ships and stock of unsold goods when it went bankrupt in 1769.

From 1768 till 1776 he made loans to the French government in the form of life annuities and by lottery operations.[13][14] His wife made him give up his share in the bank, which he transferred to his brother Louis Necker and Jean Girardot in 1772. In 1773, Necker won the prize of the Académie Française for a defense of state corporatism framed as an eulogy in honor of Louis XIV's minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert. Necker was envied by his contemporaries for his fabulous wealth.[15] His capital amonunted to six or eight million livres, and he used Château de Madrid as a summer house. In 1775, in Essai sur la législation et le commerce des grains, he attacked the physiocrats, like Ferdinando Galiani, and questioned the laissez-faire policies of Turgot, the Controller-General of Finances. Turgot had made too many enemies; in May 1776, he was dismissed. But his successor, Clugny de Nuis, died in October.[16][17] Therefore, on 22 October 1776, on the recommendation of Maurepas, Necker was appointed "Directeur du trésor royal". (As a Protestant, Necker could not serve as Controller.)[18]

Finance Minister of France

On 29 June 1777, according to his daughter in her "Vie privée de Mr. Necker" he was made director-general of the royal treasury and not Controller-General of Finance which was impossible because of his Protestant faith.[19][20] Necker refused a salary, but he was not admitted to the Royal Council. He gained popularity through regulating the government's finances by attempting to divide the taille and the capitation tax more equally, abolishing a tax known as the vingtième d'industrie, (a value-added tax) and establishing monts de piété (pawnshop-like establishments for loaning money on security). Necker tried through careful reforms (abolition of pensions, mortmain, droit de suite and more fair taxation) to rehabilitate the disorganized state budget. He abolished over five hundred sinecures and superfluous posts.[21] Together with his wife, he visited and improved life in hospitals and prisons. In April 1778 he remitted 2.4 million livres from his own fortune to the royal treasury.[22][23] Unlike Turgot - in his Mémoire sur les municipalités - Necker tried to install provincial assemblies and hoped they could serve as an effective means of reforming the Ancien régime. Necker succeeded only in Berry and Haute-Guyenne installing assemblies with an equal number of members from the Third estate.

Necker won a substantial victory by inducing the King to free all remaining serfs on the royal domain, and to invite all feudal lords to do likewise. When they refused, Necker advised Louis to abolish all serfdom in France, with indemnities to the masters, but the King, imprisoned in his traditions, replied that property rights were too basic an institution to be annulled by a decree.[24]

His greatest financial measures were his use of loans to help fund the French debt and his use of high interest rates rather than raising taxes.[25] The collection of indirect taxes was restored to the farmers-general (1780), but Necker reduced their number by a third and subjected them to sharper scrutiny and control.[26] The American War of independence was popular with almost every Frenchman, except Necker.[27] For the first time the king waged a war without raising the taxes.[28] As France in the American Revolutionary War had financed its participation almost exclusively by municipal bonds, Necker warned of the consequences for the French national budget as the war continued. (The war had cost the state already ca. 1.5 billion livres.) The ministers of War and Navy were especially hostile towards him.[29] In September 1780 Necker asked for his dismission, but the King refused to let him go.[30]

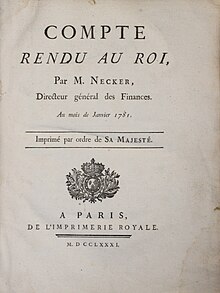

Compte rendu au roi

By 1781, France was suffering financially, and as director-general of the royal treasury he was blamed for the rather high debt accrued from the American Revolution.[31] A series of pamphlets appeared.[32] Jacques-Mathieu Augeard attacked him on his foreign origin, his faith, and economic choices.[33] The main reason behind this was the action of Necker "cooking the books" or falsifying the records.[34][35] He brightened the picture by excluding military outlays and other 'extraordinary' charges and ignoring the national debt.[36][37] Both Necker and Calonne were deceived with the amount of pensions and gratifications.[38] The king was as extravagant in expenditure on horses and palaces (he had more of both than Louis XIV) as his wife was on clothes and parties; the king spent much more on his brothers than on public health. After Necker had shown Louis XVI his annual report, the king tried to keep its contents secret. Necker met the challenge aggressively by asking the King to bring him into the royal council. In revenge, Necker made the Compte rendu au roi public; in no time between 200,000 copies were sold.[39] It was rapidly translated into Dutch, German, Danish, Italian and English.

In his most influential work, which brought him instant fame, Necker summarized governmental income and expenditures to provide the first record of royal finances ever made public. The Account was meant to be an educational piece for the people, and in it, he expressed his desire to create a well-informed, interested populace.[40] Before, the people had never considered governmental income and expenditure to be their concern, but the Compte rendu made them more proactive.

Maurepas became jealous and Vergennes called him a revolutionist. Necker declared that he would resign unless given the full title and authority of a minister, with a seat on the Conseil du Roi. Both Maurepas and Vergennes replied that they would resign if this was done.[41] When Necker was dismissed on 19 May 1781, people of all stations flocked to his home at St. Ouen. Joseph II sent his condolences and Catherine the Great invited him to Russia.[42] In August 1781 Madame Necker went as far as Utrecht to buy the libels that appeared in the name of Turgot against her husband. She even tried to have the booksellers arrested.[43][44][45] Did Necker and his brother receive annually 8 million livres as a pension?[46] In any case Jacques bought an estate in Coppet and Louis in Cologny, both near Lake Geneva. In retirement, Necker, believing in "credible policy", occupied himself with law and economics, producing his famous Traité de l'administration des finances de la France (1784). Calonne tried to prevent the spread in Paris.[47] Never had a work on such a serious a subject obtained such general success; 80.000 copies were sold.[48]

Louis XVI’s greatest problem was the French national debt. It had reached four billion livres — accumulated over many wars — and there was an annual deficit of 100 million livres. As a result, Hardman points out, in the 1780s, whereas the British government could borrow at 3. 5 per cent, the French government had to pay 6 per cent, and often more. Unless its finances were reformed, France would be unable to fight more wars.[49]

The family returned to the Paris region, supposing they were present at the wedding of their only daughter Germaine in January 1786. The impending national bankruptcy of France caused Calonne to convene an Assembly of notables under the elimination of parlements in order to enforce tax reforms. It had not met since 1626. One could not issue new loans without the Parlements' approval.[50] In his speech Calonne expressed doubts about Necker's statistics in the Compte rendu. According to him they were false and misleading,[51][52] as the state revenues had been revised upwards. For Calonne the French deficit was caused by Necker, who had not raised the taxes. However, Calonne got involved in several financial scandals regarding the "Calonne Company" and was dismissed by the king on 8 April 1787.[53] On 11 April Necker replied on the charges made by Calonne. Two days later Louis XVI banished Necker by a lettre de cachet for his very public exchange of pamphlets.[54]

[55] After two months Necker was allowed to return to Paris. Necker published his: Nouveaux éclaircissement sur le compte rendu. The next minister of finance Loménie de Brienne resigned within fifteen months, on 24 August 1788; the king allowed him an enormous pension.

On 25 or 26 August Necker was called back to office accompanied by fireworks. According to John Hardman Marie-Antoinette helped to organise Necker's return to power. This time he insisted on the title of Controller-General of Finances and access to the royal council.[56][57][58] Necker was appointed as Chief minister of France. He revoked the order of 16 August requiring bondholders to accept paper instead of money; government bonds rose 30% on the market. On 7 September Necker forbade the export of grain.[59] The bankers advanced the treasury sufficient funds to forestall a crisis over the next year. The winter of 1788-89 was one of the bitterest in history. In the summer of 1789 when the population suffered from famine Necker intervened personally and successfully at the Amsterdam bank Hope & Co. to supply the 'King of France' with grain.[60][61] The 2.4 million in the royal treasury he used as a collateral.[62] Necker's method sought a more limited monarchy along the English constitutional and financial model.[63]

The one non-noble minister

Necker succeeded in doubling the representation of the Third Estate to satisfy the nation's people. The Third Estate had as many deputies as the other two orders together. His address at the Estates-General on 5 May 1789 about the fundamental problems as financial health, constitutional monarchy, and institutional and political reforms lasted three hours. Necker suffered from a cold and after fifteen minutes he asked the secretary of the Agricultural Society to read the remainder.[64] He invited the representatives to leave aside their factional interests and take into consideration the general, long-term interests of the nation. Personal rivalries and radical claims had to give way to a pragmatic spirit of moderation and conciliation.[65] Necker's last sentence of the speech:

"Finally, gentlemen, you will not be envious of what only time can achieve, and you will leave something for it to do. For if you attempt to reform everything that seems imperfect, your work will lead to poor results."[66]

According to Simon Schama he "appeared to consider the Estates-General to be a facility designed to help the administration rather than to reform government".[67] Two weeks later Necker seems to have sought to persuade the king to adopt a constitution similar to that of England and advised him in the strongest possible terms to make the necessary concessions before it was too late.[68] According to François Mignet "He hoped to reduce the number of orders, and bring about the adoption of the English form of government, by uniting the clergy and nobility in one chamber, and the third estate in another."[69] By this refusal he became the ally of the assembly, which determined to support him. Necker warned the king that unless the privileged orders yielded, the States-General would collapse, taxes would not be paid, and the government would be bankrupt.[70]

On 17 June 1789, the first act of the new National Assembly in revolutionary France declared all existing taxes illegal. Necker had legitimate reasons to be concerned about the implications of this unprecedented decision.[71] On 23 June the king proposed to the royal council the dissolution of the Assembly. On the 11th of July, Necker received a note from the king enjoining him to leave the country within a day. He finished dining very calmly, without communicating the purport of the order he had received. According to Jean Luzac they went for a walk in a parc and from there got into their carriage to drive to their estate in Saint-Ouen at seven in the evening.[72] When the news became known the next day it enraged Camille Desmoulins. A wax-head of Necker by Philippe Curtius was taken through the streets to the Tuileries. The Royal Guard allegedly refused to salute the wax portraits and, instead, opened fire, initiating the first bloodshed of the Revolution.[73] The threat of a counter-revolution caused citizens to take up arms and storm the Bastille on 14 July.[74] The king and the Assembly recalled the immensely popular Necker to a third ministry in a letter dated 16 July.[75] Necker replied from Basle on the 23rd.[76] He wrote his brother that he was going back to the abyss. His successor,the 74-years-old Joseph Foullon de Doué was hanged from a lamppost on the 22nd. His entry into Versailles on the 29th was a day of festivity;[77] he demanded a pardon for Baron de Besenval, who was imprisoned after given command of the troops concentrated in and around Paris early July.[78]

Assignats

Necker proved to be powerless as tax-revenue dropped quickly. A first loan of thirty millions (1,200,000 livres), voted the 9th of August, had not succeeded; a subsequent loan of eighty millions (3,200,000 livres), voted the 27th of the same month, had been insufficient.[79] Credit was wrecked, according to Talleyrand; for Mirabeau "the deficit was the treasure of the nation" as it had made many changes possible. In September the treasury was empty.[80] According to Marat the whole famine was the work of one man, accusing Necker of buying up all the corn on every side, in order that Paris had none.[81] Talleyrand, the bishop of Autun proposed “national goods” should be given back to the nation.[82] In November 1789 ecclesiastical possessions were confiscated. Necker proposed to borrow from "Caisse d'Escompte", but his intention to change the private bank into a national bank as the Bank of England failed.[83][84] A general bankruptcy seemed certain.[85][86] Mirabeau proposed to LaFayette to overthrow Necker.[87] On 21 December 1789 a first decree was voted through, ordering the issue (in April 1790) of 400 million assignats, certificates of indebtedness of 1,000 livres each, with an interest rate of 5%, secured and repayable based on the auctioning of the "Biens nationaux".[88] Once the assignats were paid, they had to be destroyed or burnt. On 10 March 1790, on the proposition Pétion, the administration of the church property was transferred to the municipalities.[89] In the past few months Étienne Clavière lobbied for large issues of assignats representing national wealth and operating as legal tender.[90] For daily life smaller denominations were needed and extended to the whole of France.[91] On 17 April 1790, the new notes of 200 and 300 livres were declared legal tender but their interest was reduced to 3%.[92] The assignats would compensate for the scarcity of coin and would revive industry and trade.[93]

In May 1790 the feudal and ecclesiastical properties were sold against assignats. Constitutional monarchists such as Maury, Cazalès, Bergasse and d'Eprémesnil opposed it. The deputies in the Convention prepared a surety for future issues of paper money (on 19 June, 29 July).[94] In July, Necker proposed, as the only means, a patriotic contribution of a fourth of the revenue, to be paid at once.[95] Half of the taxes over the preceding year were still not received. People who earned more than 400 livres were invited to go to their municipality and fulfill their duty. As it was not the final cure he asked his friends, the Geneva "banquiers", to pay the arrears the Assembly turned it down.[96] The political scene came to be dominated by "clamorous spectators, passionate judges, and ungovernable agitators".[97] Necker was continuously attacked by Jean-Paul Marat in his pamphlets and by Jacques-René Hébert in his newspaper. Count Mirabeau, who played a decisive role in the Assembly, accused him of complete financial dictatorship.[98] For Mirabeau, to express doubts in the assignats, was to express doubts in the revolution.[99]

At the end of August the government was again in distress; four months after the first issue the money was spent. Montesquiou-Fézensac, the teacher of Mirabeau, presented a report in the Assembly. Assignats should be used not only for payment of church property.[100]

Necker himself argued at the National Assembly on 27 August that the assignats were a paper money which would bankrupt France.[101] Talleyrand had also attacked them on the grounds that they risked the same fate as Law's schemes. Camus stressed what he believed was the lesson of American experience of paper, which had undermined metal money and sent prices spiralling.[102] Condorcet and Dupont de Nemours argued that the assignats would drive out silver and other forms of coin, raise prices relative to paper, and thereby dangerously restrict commerce. All of these writers preferred the issue of treasury bills at interest through the Caisse d'Escompte, a revised tax-system, and increased loans.[103]

Montesquiou had massively exaggerated the amount of the redeemable debt, probably to convince the Assembly.[104] On 27 August 1790 the Assembly decided another issue of 1,9 billion assignats which would become legal tender before the end of the year. Necker endeavored to dissuade the Assembly from the proposed issue; suggesting that other means could be found for accomplishing the result, and he predicted terrible evils. Necker was not backed by Comte de Mirabeau, his strongest opponent who called for "national money" and won that day.[105] A few crowds were sent to shout and threaten him.[106] When all resources were exhausted, the Assembly created paper money, according to Necker.[107] He handed in his resignation on 3 September.[108] The massive and dangerous issue of 1,9 billion he succeeded to get down to 800 million, but the attacks influenced his resignation.[109][110] Necker did not step down on the decision to make the assignat legal tender, but on the choice to issue the paper money for the full value of the land instead of one-quarter of it, and a foul campaign against his person, and the loss of confidence in parliament.[111]

By September 1790, all authorized assignats had been paid out by the government. Supporters of the paper money argued that since the assignats were secured by land, more notes could be safely issued as long as they were retired and burned at the same rate that the lands securing them were sold. On September 29, 1790, the National Assembly authorized a further issue of 800 million livres and abolished interest on the assignats altogether.[112])

The Assembly decreed that it would itself direct the public Treasury.[113] Necker foretold that the paper money, with which the dividends were about to be paid, would soon be of no value. Du Pont de Nemours feared the emission of assignats would double the price of bread.[114][115] Since no one had truly the right to make assignats, everyone would soon begin to do so.[116] Montesquiou-Fézensac, charged with the issue of assignats, feared stockjobbing and greed.[117] A declaration (Oct 14) suspending all interest payments turned the assignats into fiat paper money proper.[118]

By September 1790, the assignat had become a true circulating paper currency, and 800 million livres worth of non-interest bearing notes were added to the initial issue, in denominations of 50, 60 70, 80, 90, 100, 500, and 2000 livres with legal-tender status. The lower denominations [25, 10, 5] were produced in large numbers in order to ensure wide circulation.[119] This change stimulated the economy but also increased inflationary pressures.[120][121]

Necker's efforts to keep the financial situation afloat were ineffective. His popularity vanished and he resigned with a damaged reputation.[122] [123] Necker left leaving two million livres in the public treasury; he took 1/5 of the amount with him.[124]

Retirement

Necker, suspected of reactionary tendencies, traveled east to Arcis-sur-Aube and Vesoul, where he was arrested and scared to death, but on 11 September he was allowed to leave the country.[125] At Coppet Castle he occupied himself with political economy, and law. At the end of 1792, he published a brochure on the trial against Louis XVI. The Neckers were far from welcome in Geneva. Many of the French émigrés considered them Jacobins, and many of the Swiss Jacobins thought them conservative.[126] Initially living in Rolle, the Necker's moved to an apartment in Beaulieu Castle.[127] (In 1793 Necker moved because of the installation of a revolutionary government in Geneva?) After being put on the list of Émigrés Necker was not paid any interest on the money he had left in the treasury.[128] His house in Rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin, his estate in Saint-Ouen sûr Seine and the two million livres were confiscated by the French government?[129] Mme Necker, who had always seen herself as ill, sank into mental illness. Since the birth of Germaine she was correcting the most morbid clauses of her will and insisted to be embalmed by Samuel-Auguste Tissot, preserved and exhibited in a bedroom for four months. [130] He continued to live under the care of his daughter. By 1794 France would be flooded by false assignats. But his time was past, and his books had except abroad no political influence.[citation needed] In 1795 Germaine moved to Paris with Benjamin Constant, but she came back, sometimes involuntary and founded the Cercle de Coppet.

In March 1798 a momentary excitement was caused by the French invasion of Switzerland when the city of Berne was attacked. Necker was treated with respect, when the army passed his mansion. In July 1798 he was removed from the list of Émigrés.[131][132] His house in the 9th arrondissement of Paris was sold to (or occupied by?) the husband of Juliette Récamier. Early June 1802 Necker met with Napoleon on his way to Marengo. In confidence, Napoleon told him about his plans to reestablish a monarchy in France. The publication of Necker's "Last Views on Politics and Finance" in 1802 upset the first consul. He threatened to exile Madame de Staël from Paris because of this book.[133][134] Although Necker had never been a republican before, toward the end of his life, he engaged seriously with the project of creating and consolidating a republic "one and indivisible" in France.[135] Necker then foretold the suppression of the Tribunat as it took place under the French Consulate. His claim of two million on the state treasury was not recognized by the French Senate.[136] Necker was buried next to his wife in the garden of Coppet Castle; the mausoleum was sealed in 1817 after Germaine had been buried there too. The Charter of 1814 signed by Louis XVIII at Saint-Ouen sûr Seine contained almost all the articles in support of liberty proposed by Necker before the Revolution of 14 July 1789.[137] Therefore, George Armstrong Kelly called him the "grandfather of Restoration Liberalism."[138]

Posterity has not been fair to Necker according to Aurelian Craiutu.[139] On 11 August 1792, the day after the Storming of the Tuileries, all the busts were removed from the town hall, including the one of Necker by Jean-Antoine Houdon and smashed.[140] Like Mirabeau, the Marquis De Lafayette, Barnave and Pétion Necker was only temporarily supported by the people.[141][142]

Personal life

His father, Karl Friedrich Necker, was a native of Küstrin in Neumark, Prussia (now Kostrzyn nad Odrą, Poland). After publishing some works, Karl Friedrich was appointed in Geneva in 1724 as a professor in public law. He started a boarding school for young Englishmen, later assisted by his son Louis Necker, a mathematician and banker.

In 1786 Necker's daughter Germaine married Erik Magnus Staël von Holstein; she was to become a prominent figure in her own right and a leading opponent of Napoleon Bonaparte. On 22 March 1814, she was promised 21 years of interest on her father's investment in the public treasury.[143] After his death his daughter published "Vie privée de Mr. Necker". His grandson Auguste de Staël (1790 – 1827) edited the Complete Oeuvres by Jacques Necker.

His nephew Jacques Necker (1757-1825), a botanist, married Albertine Necker de Saussure. They took care of their uncle after his wife had died in 1794. Their son was the geologist and crystallographer Louis Albert Necker de Saussure.[144]

Places named after Jacques Necker

Works

- Réponse au mémoire de M. l’abbé Morellet sur la Compagnie des Indes, 1769

- Éloge de Jean-Baptiste Colbert, 1773

- Sur la Législation et le commerce des grains, 1775

- Mémoire au roi sur l’établissement des administrations provinciales, 1776

- Lettre au roi, 1777

- Compte rendu au roi, 1781

- De l’Administration des finances de la France, 1784, 3 vol. in-8°

- Correspondance de M. Necker avec M. de Calonne. (29 janvier-28 février 1787), 1787

- De l’importance des opinions religieuses, 1788

- De la Morale naturelle, suivie du Bonheur des sots, 1788

- Supplément nécessaire à l’importance des opinions religieuses, 1788

- Sur le compte rendu au roi en 1781 : nouveaux éclaircissements, 1788

- Rapport fait au roi dans son conseil par le ministre des finances, 1789

- Derniers conseils au roi, 1789

- Hommage de M. Necker à la nation française, 1789

- Observations sur l’avant-propos du « Livre rouge », v. 1790

- Opinion relativement au décret de l’Assemblée nationale, concernant les titres, les noms et les armoiries, v. 1790

- Sur l’administration de M. Necker, 1791

- Réflexions présentées à la nation française sur le procès intenté à Louis XVI, 1792

- Du pouvoir exécutif dans les grands États, 1792.

- De la Révolution française, 1796. Tome 1 Tome 2

- Cours de morale religieuse, 1800

- Dernières vues de politique et de finance, offertes à la Nation française, 1802

- Manuscrits de M. Necker, publiés par sa fille (1804)

- Histoire de la Révolution française, depuis l’Assemblée des notables jusques et y compris la journée du 13 vendémiaire an IV (18 octobre 1795), 1821

Notes

- ^ Othénin d’Haussonville, p. 4

- ^ A Voice of Moderation in the Age of Revolutions: Jacques Necker’s Reflections on Executive Power in Modern Society by Aurelian Craiutu

- ^ Stael and the French Revolution Introduction by Aurelian Craiutu

- ^ Macroeconomic Features of the French Revolution, by T.J. Sargent & F.R. Velde, p. 481

- ^ A Voice of Moderation in the Age of Revolutions: Jacques Necker’s Reflections on Executive Power in Modern Society, p. 6 by Aurelian Craiutu

- ^ Brewster, David. The Edinburgh Encyclopædia, p. 316

- ^ Zeitgenossen. Biographieen und Charakteristiken p. 72

- ^ Lüthy, Herbert. Necker et la Compagnie des Indes

- ^ Margerison, Kenneth. "The Shareholders' Revolt at the Compagnie des Indes: Commerce and Political Culture in Old Regime France" in French History 20. 1, pp. 25–51. Abstract.

- ^ Réponse au Mémoire de M. l'Abbé Morellet, sur la Compagnie des Indes

- ^ Gordon, Daniel. Citizens without Sovereignty: Equality and Sociability in French Thought, p. 197

- ^ Keber, Martha L. Seas of Gold, Seas of Cotton: Christophe Poulain DuBignon of Jekyll Island p. 68

- ^ De Lapouge, Claude Vacher. Necker économiste, p.48

- ^ F. Aftalion, p. 23

- ^ Craiutu, Aurelian. A Voice of Moderation in the Age of Revolutions: Jacques Necker's Reflections on Executive Power in Modern Society

- ^ Durant, Will and Ariel (1967) Rousseau and Revolution, p. 865

- ^ F. Aftalion, p. 22

- ^ NECKER’S FIRST MINISTRY: 1776-81

- ^ Neckers Charakter und Privatleben: nebst seinen nachgelassenen ..., Band 1, p. 32

- ^ Simon Schama, Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution (New York: Random House, 1989), p. 94.

- ^ Will and Ariel Durant (1967) Rousseau and Revolution, p. 866-867

- ^ Othénin d’Haussonville (2004) “La liquidation du ‘dépôt’ de Necker: entre concept et idée-force,”, p. 154-155 Cahiers staëliens, 55

- ^ Sur l’administration de M. Necker, p. 365

- ^ Will and Ariel Durant (1967) Rousseau and Revolution, p. 866-867

- ^ Donald F. Swanson and Andrew P. Trout, "Alexander Hamilton, 'the Celebrated Mr. Neckar,' and Public Credit," The William and Mary Quarterly 47, no. 3 (1990): 424.

- ^ Will and Ariel Durant (1967) Rousseau and Revolution, p. 866-867

- ^ Will and Ariel Durant (1967) Rousseau and Revolution, p. 870

- ^ The French Revolution: An Economic Interpretation by Florin Aftalion, p. 23

- ^ F. Aftalion, p. 24

- ^ Jean-Denis Bredin (2004) “Necker, La France et la Gloire,”, p. 15 Cahiers staëliens, 55

- ^ George Taylor, review of Jacques Necker: Reform Statesman of the Ancien Regime, by Robert D. Harris, Journal of Economic History 40, no. 4 (1980): 878.

- ^ Annie Duprat, " Leonard Burnand, The pamphlet against Necker. Media and political imaginary to the xviiie century ", historical Record of the French Revolution [online], 361 | July–September 2010, published online march 22, 2011, accessed November 14, 2018. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ahrf/11742

- ^ Annie Duprat, " Leonard Burnand, The pamphlet against Necker. Media and political imaginary to the xviiie century ", historical Record of the French Revolution [online], 361 | July–September 2010, published online march 22, 2011, accessed November 14, 2018. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ahrf/11742

- ^ F. Aftalion, p. 24-25

- ^ Taylor, Jacques Necker: Reform, p. 877f.

- ^ Will and Ariel Durant (1967) Rousseau and Revolution, p. 870

- ^ S. Schama, p. 92-93

- ^ Francis Page (1797) Secret History of the French Revolution from the Convocation of the Notables ... p. 271-273

- ^ The Edinburgh Encyclopædia; Conducted by David Brewster, p. 316

- ^ Schama, Citizens, 95.

- ^ S. Schama, p. 93

- ^ Considerations on the principal events of the French Revolution Germaine de Staël

- ^ Tweede briev van Jan van Utrecht, p. 54

- ^ Annie Duprat, " Leonard Burnand, The pamphlet against Necker. Media and political imaginary to the xviiie century ", historical Record of the French Revolution [online], 361 | July–September 2010, published online march 22, 2011, accessed November 14, 2018. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ahrf/11742

- ^ The End of the Old Regime in Europe, 1776-1789, Part I: The Great States of ... by Franco Venturi, p. 348

- ^ Othénin d’Haussonville (2004) “La liquidation du ‘dépôt’ de Necker: entre concept et idée-force,”, p. 204 Cahiers staëliens, 55

- ^ Zeitgenossen: Biograhien und Charakteristiken, Ausgaben 1-4, p. 6

- ^ Considerations on the principal events of the French Revolution Germaine de Staël

- ^ How a Swiss banker’s bungling led to the French Revolution

- ^ The French Revolution: An Economic Interpretation by Florin Aftalion, p. 25

- ^ The Problem with Necker’s Compte Rendu au roi (1781) by Joël Félix

- ^ From Virtue to Surplus: Jacques Necker's Compte Rendu (1781) and the Origins of Modern Political Discourse by Jacob Soll

- ^ The French East India Company

- ^ John Hardman (2016) The life of Louis XVI

- ^ Madame de Stael by Maria Fairweather

- ^ Will and Ariel Durant (1967) Rousseau and Revolution, p. 948

- ^ Madame de Stael by Maria Fairweather

- ^ Jacques Necker

- ^ Will and Ariel Durant (1967) Rousseau and Revolution, p. 949

- ^ At Spes non Fracta: Hope & Co. 1770–1815, p. 46 by M.G. Buist

- ^ Othénin d’Haussonville (2004) “La liquidation du ‘dépôt’ de Necker: entre concept et idée-force,”, p. 156 Cahiers staëliens, 55

- ^ Neckers Charakter und Privatleben: nebst seinen nachgelassenen ..., Band 1, p. 83

- ^ Overture to Revolution: The 1787 Assembly of Notables and the Crisis of France's Old Regime. By John Hardman. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- ^ Wikisource

- ^ Aurelian Craiutu (2012) A Virtue for Courageous Minds: Moderation in French Political Thought, 1748-1830, p. 119-121

- ^ R.D. Harris (1986) Necker and the Revolution of 1789, p. 433-434

- ^ Schama, Citizens, 345–46.

- ^ Aurelian Craiutu (2012) A Virtue for Courageous Minds: Moderation in French Political Thought, 1748-1830, p. 123

- ^ History of the French Revolution from 1789 to 1814 by M. Mignet

- ^ Will and Ariel Durant (1967) Rousseau and Revolution, p. 958

- ^ Aurelian Craiutu (2012) A Virtue for Courageous Minds: Moderation in French Political Thought, 1748-1830, p. 124

- ^ Gazette de Leyde - Livraison n° 58 du 21 juillet 1789

- ^ Paris Amanda Spies-Gans, “‘The Fullest Imitation of Life’: Reconsidering Marie Tussaud, Artist-Historian of the French Revolution,” Journal 18, Issue 3 Lifelike (Spring 2017), http://www.journal18.org/1438. DOI: 10.30610/3.2017.8

- ^ Godechot, Jacques. The Taking of the Bastille July 14, 1789.

- ^ De la Révolution française, Band 2 by Jacques Necker, p. 13

- ^ Briefe und Urkunden von Ludwig XVI., Marie Antoinette und Madame Elisabeth, p. 410

- ^ Gazette de Leyde - Livraison n° 63 du 7 août 1789

- ^ History of the French revolution of 1789, Band 1 , p. 568

- ^ History of the French Revolution from 1789 to 1814 by M. Mignet

- ^ François Crouzet (1993) La grande inflation : La monnaie en France de Louis XVI à Napoléon, p. 97-98

- ^ Historical View of the French Revolution: From Its Earliest Indications to ... by Jules Michelet, p. 248

- ^ Crouzet, F. (1993) La grande inflation, p. 101

- ^ Crouzet, F. (1993) La grande inflation, p. 104-105

- ^ F. Aftalion, p. 64

- ^ The French Revolution: An Economic Interpretation by Florin Aftalion, p. 59

- ^ Stuff and Money in the Time of the French Revolution by Rebecca L. Spang

- ^ Historical View of the French Revolution: From Its Earliest Indications to ... by Jules Michelet, p. 288

- ^ THE FRENCH REVOLUTION, THE ASSIGNATS, AND THE COUNTERFEITERS

- ^ Crouzet, F. (1993) La grande inflation, p. 110

- ^ Whatmore, Richard (1996) “Commerce, Constitutions, and the Manners of a Nation: Etienne Clavière's Revolutionary Political Economy, 1788–1793.” History of European Ideas 22.5-6 (1996): 351–368. Web.

- ^ F. Aftalion, p. 95

- ^ The French Revolution: An Economic Interpretation by Florin Aftalion, p. xii

- ^ The French Revolution: An Economic Interpretation by Florin Aftalion, p. 80, 95

- ^ The French Revolution: An Economic Interpretation by Florin Aftalion, p. 76

- ^ History of the French Revolution from 1789 to 1814 by M. Mignet

- ^ Crouzet, F. (1993) La grande inflation, p. 99

- ^ Aurelian Craiutu (2012) A Virtue for Courageous Minds: Moderation in French Political Thought, 1748-1830, p. 130

- ^ Simon Schama (1989) Citizens, p. 499, 536

- ^ E. Levasseur (1894) The Assignats: A Study in the Finances of the French Revolution, p. 183. In: Journal of Political Economy. Vol. 2, No. 2

- ^ F. Aftalion, p. 77

- ^ 'Contre l'émission de dix-neuf cents millions d'assignats', Œuvres complètes de Jacques Necker (Paris, 1821), vii, 430-447.

- ^ De l'opinion de M. Camus, (Paris, 1789)

- ^ Whatmore, Richard (1996) “Commerce, Constitutions, and the Manners of a Nation: Etienne Clavière's Revolutionary Political Economy, 1788–1793.” History of European Ideas 22.5-6 (1996): 351–368. Web.

- ^ F. Aftalion, p. 78

- ^ A.D. White (1878) The Assignat|Ann Arbor Library

- ^ Historical View of the French Revolution: From Its Earliest Indications to ... by Jules Michelet, p. 487

- ^ F. Aftalion, p. 84-85

- ^ Considerations on the principal events of the French Revolution Germaine de Staël, p. 256-258

- ^ Crouzet, F. (1993) La grande inflation, p. 115

- ^ Histoire de la révolution française: depuis l'Assemblée des notables ... by Jacques Necker, p. 35

- ^ Histoire de la Révolution française par Henri Martin, p. 214

- ^ Guide to the French Currency Collection 1791-1796. University of Chicago Library (2012)

- ^ Historical View of the French Revolution: From Its Earliest Indications to ... by Jules Michelet, p. 487

- ^ The Money and the Finances of the French Revolution of 1789: Assignats and Mandats: A True History: Including an Examination of Dr. Andrew D. White's Paper Money Inflation in France by Stephen Devalson Dillaye, p. 18

- ^ F. Aftalion, p. 81

- ^ Stuff and Money in the Time of the French Revolution by Rebecca L. Spang

- ^ Opinion de M. de Montesquiou sur les assignats-monnoie..., p. 3

- ^ THE HISTORY OF ECONOMIC THOUGHT WEBSITE

- ^ Collection Complète des Lois, Décrets, Ordonnances, Réglements, p. 35

- ^ Tales from the Vault: Money of the French Revolution – the Assignat by Douglas Mudd, ANA Money Museum curator / museum director

- ^ Assignats

- ^ Furet and Ozuof, A Critical Dictionary,288.

- ^ Doyle, William. The French Revolution. A Very Short Introduction.

- ^ Histoire de la révolution française: depuis l'Assemblée des notables ... by Jacques Necker, p. 31

- ^ Historical Review of the Administration of Mr. Necker by Jacques Necker, p. 373

- ^ The Encyclopedists as individuals: a biographical dictionary of the authors of the Encyclopédie

- ^ The Miscellaneous Works of Edward Gibbon: With Memoirs of His Life ..., Band 2 by Edward Gibbon, p. 460, 483

- ^ Othénin d’Haussonville (2004) “La liquidation du ‘dépôt’ de Necker: entre concept et idée-force,”, p. 156-158 Cahiers staëliens, 55

- ^ Othénin d’Haussonville, p. 162-163

- ^ Glory and Terror: Seven Deaths Under the French Revolution by Antoine de Baecque

- ^ Othénin d’Haussonville, p. 169

- ^ Considerations on the principal events of the French Revolution Germaine de Staël, p. 418-420

- ^ Considerations on the Principal Events of the French Revolution ..., Volume 2 by Madame de Staël, p. 35-36, 42

- ^ Considerations on the principal events of the French Revolution Germaine de Staël, p. 459

- ^ Aurelian Craiutu (2012) A Virtue for Courageous Minds: Moderation in French Political Thought, 1748-1830, p. 145

- ^ Othénin d’Haussonville, p. 177

- ^ Considerations on the Principal Events of the French Revolution ..., Volume 2 by Madame de Staël, p. 148

- ^ Kelly, George A. (1965). "Liberalism and Aristocracy in the French Restoration". Journal of the History of Ideas. 26 (4): 510.

- ^ A Voice of Moderation in the Age of Revolutions: Jacques Necker’s Reflections on Executive Power in Modern Society by Aurelian Craiutu

- ^ Jean-Antoine Houdon: Sculptor of the Enlightenment by Anne L. Poulet, p. 351

- ^ Jonathan Israel (2015) Revolutionary Ideas, p. ?

- ^ Positive principles of Mr. Neker, extracted from all his works

- ^ Othénin d’Haussonville, p. 195, 205

- ^ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0 902 198 84 X.

Further reading

- Furet, François, and Mona Ozuof. A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution. (Belknap Press, 1989) pp 287–97

- Harris, Robert D. Necker and the Revolution of 1789 (Lanham, MD, 1986)

- Lefebvre, Georges. The French Revolution: From its Origins to 1793. London: Routledge Classics, 2001.

- Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York: Random House, 1989, chapter Two, V: Last Best Hopes: The Banker

- Swanson, Donald F, and Andrew P. Trout. “Alexander Hamilton, the Celebrated Mr. Neckar,’ and Public Credit.” The William and Mary Quarterly (1990) 47#3 pp 422–430. in JSTOR

- Taylor, George. Review of Jacques Necker: Reform Statesman of the Ancien Regime, by Robert D. Harris. Journal of Economic History 40, no. 4 (1980): 877–879. doi:10.1017/s0022050700100518

- In French

- (in French) Bredin, Jean-Denis. Une singulière famille: Jacques Necker, Suzanne Necker et Germaine de Staël. Paris: Fayard, 1999 (ISBN 2-213-60280-8).

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Jacques Necker. Bibliography of Necker's publications.

- Full text of Principes positifs de M. Neker … Positive principles of Mr. Neker, extracted from all his works