Kidney transplantation

| Kidney transplantation | |

|---|---|

| |

| Specialty | Nephrology, transplantology |

| ICD-10-PCS | OTY |

| ICD-9-CM | 55.6 |

| MeSH | D016030 |

| OPS-301 code | 5-555 |

| MedlinePlus | 003005 |

Kidney transplantation or renal transplantation is the organ transplant of a kidney into a patient with end-stage renal disease. Kidney transplantation is typically classified as deceased-donor (formerly known as cadaveric) or living-donor transplantation depending on the source of the donor organ. Living-donor renal transplants are further characterised as genetically related (living-related) or non-related (living-unrelated) transplants, depending on whether a biological relationship exists between the donor and recipient. Exchanges and chains are a novel approach to expand the living donor pool. In February of 2012, this novel approach to expand the living donor pool was featured on the front page of the New York Times in a story covering the largest chain in the world involving 60 participants organized by the National Kidney Registry.[1] In 2014 the record for the largest chain was broken again by a swap involving 70 participants, covered by ABC News.[2]

History

One of the earliest mentions about the real possibility of a kidney transplant was by American medical researcher Simon Flexner, who declared in a reading of his paper on “Tendencies in Pathology” in the University of Chicago in 1907 that it would be possible in the then-future for diseased human organs substitution for healthy ones by surgery — including arteries, stomach, kidneys and heart.[3]

In 1933 surgeon Yuriy Voroniy from Kherson in the Soviet Union attempted the first human kidney transplant, using a kidney removed 6 hours earlier from the deceased donor to be reimplanted into the thigh. He measured kidney function using a connection between the kidney and the skin. His first patient died 2 days later as the graft was incompatible with the recipient's blood group and was rejected.[4]

It was not until June 17, 1950, when a successful transplant could be performed on Ruth Tucker, a 44-year-old woman with polycystic kidney disease, at Little Company of Mary Hospital in Evergreen Park, Illinois. Although the donated kidney was rejected ten months later because no immunosuppressive therapy was available at the time—the development of effective antirejection drugs was years away—the intervening time gave Tucker's remaining kidney time to recover and she lived another five years.[5]

The first kidney transplants between living patients were undertaken in 1952 at the Necker hospital in Paris by Jean Hamburger although the kidney failed after 3 weeks of good function [6] and later in 1954 in Boston. The Boston transplantation, performed on December 23, 1954, at Brigham Hospital was performed by Joseph Murray, J. Hartwell Harrison, John P. Merrill and others. The procedure was done between identical twins Ronald and Richard Herrick to eliminate any problems of an immune reaction. For this and later work, Dr. Murray received the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1990. The recipient, Richard Herrick, died eight years after the transplantation.[7]

In 1955, Charles Rob, William James 'Jim' Dempster (St Marys and Hammersmith, London) carried out the first deceased donor transplant in United Kingdom, which was unsuccessful. In July 1959, 'Fred' Peter Raper (Leeds) performed first successful (8 months) deceased donor transplant in the UK. A year later, in 1960, the first successful living kidney transplant in the UK occurred, when Michael Woodruff performed one between identical twins in Edinburgh.[8] Until the routine use of medications to prevent and treat acute rejection, introduced in 1964, deceased donor transplantation was not performed. The kidney was the easiest organ to transplant: tissue typing was simple, the organ was relatively easy to remove and implant, live donors could be used without difficulty, and in the event of failure, kidney dialysis was available from the 1940s. Tissue typing was essential to the success: early attempts in the 1950s on sufferers from Bright's disease had been very unsuccessful.

The major barrier to organ transplantation between genetically non-identical patients lay in the recipient's immune system, which would treat a transplanted kidney as a "non-self" and immediately or chronically reject it. Thus, having medications to suppress the immune system was essential. However, suppressing an individual's immune system places that individual at greater risk of infection and cancer (particularly skin cancer and lymphoma), in addition to the side effects of the medications.

The basis for most immunosuppressive regimens is prednisolone, a corticosteroid. Prednisolone suppresses the immune system, but its long-term use at high doses causes a multitude of side effects, including glucose intolerance and diabetes, weight gain, osteoporosis, muscle weakness, hypercholesterolemia, and cataract formation. Prednisolone alone is usually inadequate to prevent rejection of a transplanted kidney. Thus other, non-steroid immunosuppressive agents are needed, which also allow lower doses of prednisolone.

Indications

The indication for kidney transplantation is end-stage renal disease (ESRD), regardless of the primary cause. This is defined as a glomerular filtration rate <15ml/min/1.73 sq.m. Common diseases leading to ESRD include malignant hypertension, infections, diabetes mellitus, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; genetic causes include polycystic kidney disease, a number of inborn errors of metabolism, and autoimmune conditions such as lupus. Diabetes is the most common known cause of kidney transplantation, accounting for approximately 25% of those in the US. The majority of renal transplant recipients are on dialysis (peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis) at the time of transplantation. However, individuals with chronic kidney disease who have a living donor available may undergo pre-emptive transplantation before dialysis is needed. If a patient is put on the waiting list for a deceased donor transplant early enough, they may also be transplanted pre-dialysis.

Contraindications and requirements

Contraindications include both cardiac and pulmonary insufficiency, as well as hepatic disease and some cancers. Concurrent tobacco use and morbid obesity are also among the indicators putting a patient at a higher risk for surgical complications.

Kidney transplant requirements vary from program to program and country to country. Many programs place limits on age (e.g. the person must be under a certain age to enter the waiting list) and require that one must be in good health (aside from the kidney disease). Significant cardiovascular disease, incurable terminal infectious diseases and cancer are often transplant exclusion criteria. In addition, candidates are typically screened to determine if they will be compliant with their medications, which is essential for survival of the transplant. People with mental illness and/or significant on-going substance abuse issues may be excluded.

HIV was at one point considered to be a complete contraindication to transplantation. There was fear that immunosuppressing someone with a depleted immune system would result in the progression of the disease. However, some research seem to suggest that immunosuppressive drugs and antiretrovirals may work synergistically to help both HIV viral loads/CD4 cell counts and prevent active rejection.

Sources of kidneys

Since medication to prevent rejection is so effective, donors do not need to be similar to their recipient. Most donated kidneys come from deceased donors; however, the utilisation of living donors in the United States is on the rise. In 2006, 47% of donated kidneys were from living donors.[9] This varies by country: for example, only 3% of kidneys transplanted during 2006 in Spain came from living donors.[10]

Living donors

Approximately one in three donations in the US, UK, and Israel is now from a live donor.[11][12][13] Potential donors are carefully evaluated on medical and psychological grounds. This ensures that the donor is fit for surgery and has no disease which brings undue risk or likelihood of a poor outcome for either the donor or recipient. The psychological assessment is to ensure the donor gives informed consent and is not coerced. In countries where paying for organs is illegal, the authorities may also seek to ensure that a donation has not resulted from a financial transaction.

The relationship the donor has to the recipient has evolved over the years. In the 1950s, the first successful living donor transplants were between identical twins. In the 1960s–1970s, live donors were genetically related to the recipient. However, during the 1980s–1990s, the donor pool was expanded further to emotionally related individuals (spouses, friends). Now the elasticity of the donor relationship has been stretched to include acquaintances and even strangers ('altruistic donors'). In 2009, Minneapolis transplant recipient Chris Strouth received a kidney from a donor who connected with him on Twitter, which is believed to be the first such transplant arranged entirely through social networking.[14][15]

The acceptance of altruistic donors has enabled chains of transplants to form. Kidney chains are initiated when an altruistic donor donates a kidney to a patient who has a willing but incompatible donor. This incompatible donor then 'pays it forward' and passes on the generosity to another recipient who also had a willing but incompatible donor. Michael Rees from the University of Toledo developed the concept of open-ended chains.[16] This was a variation of a concept developed at Johns Hopkins University.[17] On July 30, 2008, an altruistic donor kidney was shipped via commercial airline from Cornell to the University of California, Los Angeles, thus triggering a chain of transplants.[18] The shipment of living donor kidneys, computer-matching software algorithms, and cooperation between transplant centers has enabled long-elaborate chains to be formed.[19]

In carefully screened kidney donors, survival and the risk of end-stage renal disease appear to be similar to those in the general population.[20] However, women who have donated a kidney have a higher risk of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia than matched nondonors with similar indicators of baseline health.[21] Traditionally, the donor procedure has been through a single incision of 4–7 inches (10–18 cm)*, but live donation is being increasingly performed by laparoscopic surgery. This reduces pain and accelerates recovery for the donor. Operative time and complications decreased significantly after a surgeon performed 150 cases. Live donor kidney grafts have higher long-term success rates than those from deceased donors.[22] Since the increase in the use of laparoscopic surgery, the number of live donors has increased. Any advance which leads to a decrease in pain and scarring and swifter recovery has the potential to boost donor numbers. In January 2009, the first all-robotic kidney transplant was performed at Saint Barnabas Medical Center through a two-inch incision. In the following six months, the same team performed eight more robotic-assisted transplants.[23]

In 2004 the FDA approved the Cedars-Sinai High Dose IVIG therapy which reduces the need for the living donor to be the same blood type (ABO compatible) or even a tissue match.[24][25] The therapy reduced the incidence of the recipient's immune system rejecting the donated kidney in highly sensitized patients.[25]

In 2009 at the Johns Hopkins Medical Center, a healthy kidney was removed through the donor's vagina. Vaginal donations promise to speed recovery and reduce scarring.[26] The first donor was chosen as she had previously had a hysterectomy.[27] The extraction was performed using natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery, where an endoscope is inserted through an orifice, then through an internal incision, so that there is no external scar. The recent advance of single port laparoscopy requiring only one entry point at the navel is another advance with potential for more frequent use.

Organ trade

In the developing world some people sell their organs illegally. Such people are often in grave poverty[28] or are exploited by salespersons. The people who travel to make use of these kidneys are often known as 'transplant tourists'. This practice is opposed by a variety of human rights groups, including Organs Watch, a group established by medical anthropologists, which was instrumental in exposing illegal international organ selling rings. These patients may have increased complications owing to poor infection control and lower medical and surgical standards. One surgeon has said that organ trade could be legalised in the UK to prevent such tourism, but this is not seen by the National Kidney Research Fund as the answer to a deficit in donors.[29]

In the illegal black market the donors may not get sufficient after-operation care,[30] the price of a kidney may be above $160,000,[31] middlemen take most of the money, the operation is more dangerous to both the donor and receiver, and the buyer often gets hepatitis or HIV.[32] In legal markets of Iran the price of a kidney is $2,000 to $4,000.[32][33]

An article by Gary Becker and Julio Elias on "Introducing Incentives in the market for Live and Cadaveric Organ Donations"[34] said that a free market could help solve the problem of a scarcity in organ transplants. Their economic modeling was able to estimate the price tag for human kidneys ($15,000) and human livers ($32,000).

Now monetary compensation for organ donors is being legalised in Australia and Singapore too. Kidney disease organisations in both countries have expressed their support.[35][36]

Deceased donors

Deceased donors can be divided in two groups:

- Brain-dead (BD) donors

- Donation after Cardiac Death (DCD) donors

Although brain-dead (or 'heart beating') donors are considered dead, the donor's heart continues to pump and maintain the circulation. This makes it possible for surgeons to start operating while the organs are still being perfused (supplied blood). During the operation, the aorta will be cannulated, after which the donor's blood will be replaced by an ice-cold storage solution, such as UW (Viaspan), HTK, or Perfadex. Depending on which organs are transplanted, more than one solution may be used simultaneously. Due to the temperature of the solution, and since large amounts of cold NaCl-solution are poured over the organs for a rapid cooling, the heart will stop pumping.

'Donation after Cardiac Death' donors are patients who do not meet the brain-dead criteria but, due to the unlikely chance of recovery, have elected via a living will or through family to have support withdrawn. In this procedure, treatment is discontinued (mechanical ventilation is shut off). After a time of death has been pronounced, the patient is rushed to the operating room where the organs are recovered. Storage solution is flushed through the organs. Since the blood is no longer being circulated, coagulation must be prevented with large amounts of anti-coagulation agents such as heparin. Several ethical and procedural guidelines must be followed; most importantly, the organ recovery team should not participate in the patient's care in any manner until after death has been declared.

Compatibility

In general, the donor and recipient should be ABO blood group and crossmatch (HLA antigen) compatible. If a potential living donor is incompatible with their recipient, the donor could be exchange for a compatible kidney. Kidney exchange, also known as "kidney paired donation" or "chains" had recently gained popularity over the past few years.

In an effort to reduce the risk of rejection during incompatible transplantation, ABO-incompatible and densensitization protocols utilizing intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) have been developed, with the aim to reduce ABO and HLA antibodies that the recipient may have to the donor.

In the 1980s, experimental protocols were developed for ABO-incompatible transplants using increased immunosuppression and plasmapheresis. Through the 1990s these techniques were improved and an important study of long-term outcomes in Japan was published ([1]). Now, a number of programs around the world are routinely performing ABO-incompatible transplants.[37]

The level of sensitization to donor HLA antigens is determined by performing a panel reactive antibody test on the potential recipient. In the United States, up to 17% of all deceased donor kidney transplants have no HLA mismatch. However, HLA matching is a relatively minor predictor of transplant outcomes. In fact, living non-related donors are now almost as common as living (genetically)-related donors.

Procedure

In most cases the barely functioning existing kidneys are not removed, as this has been shown to increase the rates of surgical morbidity. Therefore, the kidney is usually placed in a location different from the original kidney, often in the iliac fossa, so it is often necessary to use a different blood supply:

- The renal artery of the new kidney, previously branching from the abdominal aorta in the donor, is often connected to the external iliac artery in the recipient.

- The renal vein of the new kidney, previously draining to the inferior vena cava in the donor, is often connected to the external iliac vein in the recipient.

There is disagreement in surgical textbooks regarding which side of the recipient’s pelvis to use in receiving the transplant. Campbell's Urology (2002) recommends placing the donor kidney in the recipient’s contralateral side (i.e. a left sided kidney would be transplanted in the recipient's right side) to ensure the renal pelvis and ureter are anterior in the event that future surgeries are required. In an instance where there is doubt over whether there is enough space in the recipient’s pelvis for the donor's kidney, the textbook recommends using the right side because the right side has a wider choice of arteries and veins for reconstruction. Smith's Urology (2004) states that either side of the recipient's pelvis is acceptable; however the right vessels are 'more horizontal' with respect to each other and therefore easier to use in the anastomoses. It is unclear what is meant by the words 'more horizontal'. Glen's Urological Surgery (2004) recommends putting the kidney in the contralateral side in all circumstances. No reason is explicitly put forth; however, one can assume the rationale is similar to that of Campbell', i.e. to ensure that the renal pelvis and ureter are most anterior in the event that future surgical correction becomes necessary.

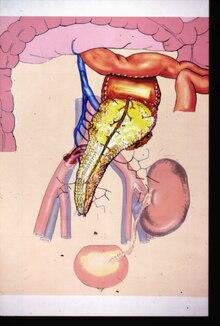

Kidney-pancreas transplant

Occasionally, the kidney is transplanted together with the pancreas. University of Minnesota surgeons Richard Lillehei and William Kelly perform the first successful simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant in the world in 1966.[38] This is done in patients with diabetes mellitus type 1, in whom the diabetes is due to destruction of the beta cells of the pancreas and in whom the diabetes has caused renal failure (diabetic nephropathy). This is almost always a deceased donor transplant. Only a few living donor (partial) pancreas transplants have been done. For individuals with diabetes and renal failure, the advantages of earlier transplant from a living donor (if available) are far superior to the risks of continued dialysis until a combined kidney and pancreas are available from a deceased donor.[citation needed] A patient can either receive a living kidney followed by a donor pancreas at a later date (PAK, or pancreas-after-kidney) or a combined kidney-pancreas from a donor (SKP, simultaneous kidney-pancreas).

Transplanting just the islet cells from the pancreas is still in the experimental stage, but shows promise. This involves taking a deceased donor pancreas, breaking it down, and extracting the islet cells that make insulin. The cells are then injected through a catheter into the recipient and they generally lodge in the liver. The recipient still needs to take immunosuppressants to avoid rejection, but no surgery is required. Most people need two or three such injections, and many are not completely insulin-free.

Post operation

The transplant surgery takes about three hours.[39] The donor kidney will be placed in the lower abdomen and its blood vessels connected to arteries and veins in the recipient's body. When this is complete, blood will be allowed to flow through the kidney again. The final step is connecting the ureter from the donor kidney to the bladder. In most cases, the kidney will soon start producing urine.

Depending on its quality, the new kidney usually begins functioning immediately. Living donor kidneys normally require 3–5 days to reach normal functioning levels, while cadaveric donations stretch that interval to 7–15 days. Hospital stay is typically for 4–10 days. If complications arise, additional medications (diuretics) may be administered to help the kidney produce urine.

Immunosuppressant drugs are used to suppress the immune system from rejecting the donor kidney. These medicines must be taken for the rest of the recipient's life. The most common medication regimen today is a mixture of tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisolone. Some recipients may instead take ciclosporin, sirolimus, or azathioprine. Ciclosporin, considered a breakthrough immunosuppressive when first discovered in the 1980s, ironically causes nephrotoxicity and can result in iatrogenic damage to the newly transplanted kidney. Tacrolimus, which is a similar drug, also causes nephrotoxicity. Blood levels of both must be monitored closely and if the recipient seems to have declining renal function or proteinuria, a biopsy may be necessary to determine whether this is due to rejection [40][41] or ciclosporin or tacrolimus intoxication .

Postoperative diet

Kidney transplant recipients are discouraged from consuming grapefruit, pomegranate and green tea products. These food products are known to interact with the transplant medications, specifically tacrolimus, cyclosporin and sirolimus; the blood levels of these drugs may be increased, potentially leading to an overdose.[42]

Acute rejection occurs in 10–25% of people after transplant during the first 60 days.[citation needed] Rejection does not necessarily mean loss of the organ, but it may necessitate additional treatment and medication adjustments.[43]

Complications

Problems after a transplant may include: Post operative complication, bleeding, infection, vascular thrombosis and urinary complications

- Transplant rejection (hyperacute, acute or chronic)

- Infections and sepsis due to the immunosuppressant drugs that are required to decrease risk of rejection

- Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (a form of lymphoma due to the immune suppressants)

- Imbalances in electrolytes including calcium and phosphate which can lead to bone problems

- Proteinuria[41]

- Hypertension

- Other side effects of medications including gastrointestinal inflammation and ulceration of the stomach and esophagus, hirsutism (excessive hair growth in a male-pattern distribution) with ciclosporin, hair loss with tacrolimus, obesity, acne, diabetes mellitus type 2, hypercholesterolemia, and osteoporosis.

A patient's age and health condition before transplantation affect the risk of complications. Different transplant centers have different success at managing complications and therefore, complication rates are different from center to center.

The average lifetime for a donated kidney is ten to fifteen years. When a transplant fails, a patient may opt for a second transplant, and may have to return to dialysis for some intermediary time.

Infections due to the immunosuppressant drugs used in people with kidney transplants most commonly occur in mucocutaneous areas (41%), the urinary tract (17%) and the respiratory tract (14%).[44] The most common infective agents are bacterial (46%), viral (41%), fungal (13%), and protozoan (1%).[44] Of the viral illnesses, the most common agents are human cytomegalovirus (31.5%), herpes simplex (23.4%), and herpes zoster (23.4%).[44] BK virus is now being increasingly recognised. Infection is the cause of death in about one third of people with renal transplants, and pneumonias account for 50% of the patient deaths from infection.[44]

Prognosis

Kidney transplantation is a life-extending procedure.[45] The typical patient will live 10 to 15 years longer with a kidney transplant than if kept on dialysis.[46] The increase in longevity is greater for younger patients, but even 75-year-old recipients (the oldest group for which there is data) gain an average four more years of life. People generally have more energy, a less restricted diet, and fewer complications with a kidney transplant than if they stay on conventional dialysis.

Some studies seem to suggest that the longer a patient is on dialysis before the transplant, the less time the kidney will last. It is not clear why this occurs, but it underscores the need for rapid referral to a transplant program. Ideally, a kidney transplant should be pre-emptive, i.e., take place before the patient begins dialysis. The reason why kidneys fail over time after transplantation has been elucidated in recent years. Apart from recurrence of the original kidney disease, also rejection (mainly antibody-mediated rejection) and progressive scarring (multifactorial) play a decisive role.[47] Avoiding rejection by strict medication adherence is of utmost importance to avoid failure of the kidney transplant.

At least four professional athletes have made a comeback to their sport after receiving a transplant: New Zealand rugby union player Jonah Lomu, German-Croatian Soccer Player Ivan Klasnić, and NBA basketballers Sean Elliott and Alonzo Mourning.[citation needed]

Statistics

| Country | Year | Cadaveric donor | Living donor | Total transplants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada[48] | 2000 | 724 | 388 | 1,112 |

| France[49] | 2003 | 1,991 | 136 | 2,127 |

| Italy[49] | 2003 | 1,489 | 135 | 1,624 |

| Japan[50] | 2010 | 208 | 1276 | 1,484 |

| Spain[49] | 2003 | 1,991 | 60 | 2,051 |

| United Kingdom[49] | 2003 | 1,297 | 439 | 1,736 |

| United States[51] | 2008 | 10,551 | 5,966 | 16,517 |

| Pakistan – SIUT[52][citation needed] | 2008 | 1,854 | 1,932 |

- Robert Perry remains the longest-surviving American kidney recipient from an unrelated donor, having received his kidney in 1974 at age 23; he survived over 41 years, dying 31 May 2015.[53]

In addition to nationality, transplantation rates differ based on race, sex, and income. A study done with patients beginning long-term dialysis showed that the socio-demographic barriers to renal transplantation are relevant even before patients are on the transplant list.[54] For example, different socio-demographic groups express different interest and complete pre-transplant workup at different rates. Previous efforts to create fair transplantation policies have focused on patients currently on the transplantation waiting list.

In the U.S. health system

Transplant recipients must take immunosuppressive anti-rejection drugs for as long as the transplanted kidney functions. The routine immunosuppressives are tacrolimus (Prograf), mycophenolate (Cellcept), and prednisolone; these drugs cost US$1,500 per month. In 1999 the United States Congress passed a law that restricts Medicare from paying for more than three years for these drugs, unless the patient is otherwise Medicare-eligible. Transplant programs may not transplant a patient unless the patient has a reasonable plan to pay for medication after the Medicare expires; however, patients are almost never turned down for financial reasons alone. Half of end-stage renal disease patients only have Medicare coverage.

In March 2009 a bill was introduced in the U.S. Senate, 565 and in the House, H.R. 1458 that will extend Medicare coverage of the drugs for as long as the patient has a functioning transplant. This means that patients who have lost their jobs and insurance will not also lose their kidney and be forced back on dialysis. Dialysis is currently using up $17 billion yearly of Medicare funds and total care of these patients amounts to over 10% of the entire Medicare budget.

The United Network for Organ Sharing, which oversees the organ transplants in the United States, allows transplant candidates to register at two or more transplant centers, a practice known as 'multiple listing'.[55] The practice has been shown to be effective in mitigating the dramatic geographic disparity in the waiting time for organ transplants,[56] particularly for patients residing in high-demand regions such as Boston.[57] The practice of multiple-listing has also been endorsed by medical practitioners.[58][59]

See also

- Gurgaon kidney scandal

- Jesus Christians – An Australian religious group, many of whose members have donated a kidney to a stranger

- Liver transplantation

Bibliography

- Brook, Nicholas R.; Nicholson, Michael L. (2003). "Kidney transplantation from non heart-beating donors". Surgeon. 1 (6): 311–322. doi:10.1016/S1479-666X(03)80065-3. PMID 15570790.

- Danovitch, Gabriel M.; Delmonico, Francis L. (2008). "The prohibition of kidney sales and organ markets should remain". Current Opinion in Organ Transplantation. 13 (4): 386–394. doi:10.1097/MOT.0b013e3283097476. PMID 18685334.

- El-Agroudy, Amgad E.; El-Husseini, Amr A.; El-Sayed, Moharam; Ghoneim, Mohamed A. (2003). "Preventing Bone Loss in Renal Transplant Recipients with Vitamin D". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 14 (11): 2975–2979. doi:10.1097/01.ASN.0000093255.56474.B4. PMID 14569109.

- El-Agroudy, Amgad E.; Sabry, Alaa A.; Wafa, Ehab W.; Neamatalla, Ahmed H.; Ismail, Amani M.; Mohsen, Tarek; Khalil, Abd Allah; Shokeir, Ahmed A.; Ghoneim, Mohamed A. (2007). "Long-term follow-up of living kidney donors: a longitudinal study". BJU International. 100 (6): 1351–1355. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07054.x. ISSN 1464-4096. PMID 17941927.

- Kerry Grens, "Living kidney donations favor some patient groups: study", 'Reuters', Apr 9, 2012. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/04/10/health-kidney-donations-idUSL3E8FA0A720120410

- Gore John L, et al. (2012). ", "The Socioeconomic Status of Donors and Recipients of Living Unrelated Renal Transplants in the United States". The Journal of Urology. 187 (5): 1760–1765. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2011.12.112.

Notes

- ^ Sack, Kevin (18 Feb 2012). "60 Lives, 30 Kidneys, All Linked". New York Times.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Pitts, Byron (15 Apr 2015). "Changing Lives Through Donating Kidneys to Strangers". ABC News Nightline.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ MAY TRANSPLANT THE HUMAN HEART (.PDF), The New York Times, January 2, 1908

- ^ "Surgeon Yurii Voronoy (1895–1961) – a pioneer in the history of clinical transplantation: in Memoriam at the 75th Anniversary of the First Human Kidney Transplantation". Transplant International. 22: 1132–1139. Dec 2009. doi:10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00986.x. PMID 19874569.

- ^ David Petechuk (2006). Organ transplantation. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 11. ISBN 0-313-33542-7.

- ^ Legendre, Ch; Kreis, H. (November 2010). "A Tribute to Jean Hamburger's Contribution to Organ Transplantation". American Journal of Transplantation. 10 (11): 2392–2395. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03295.x. PMID 20977631.

- ^ "Transplant Pioneers Recall Medical Milestone". NPR. December 20, 2004. Retrieved 2010-12-20.

- ^ Hakim, Nadey (2010). Living Related Transplantation. World Scientific. p. 39. ISBN 1-84816-497-1.

- ^ Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, 2007

- ^ Organización Nacional de Transplantes (ONT), 2007

- ^ "How to become an organ donor". The Sentinel. 24 February 2009. Retrieved 2010-12-19.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P1-5994618.html Judy Siegel, "Live liver and lung donations approved. New regulations will give hope to dozens." 'Jerusalem Post', 09-05-1995 "(subscription required)

- ^ "National Data Reports". The Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (OPTN). dynamic. Retrieved 22 Oct 2013. (the link is to a query interface; Choose Category = Transplant, Organ = Kidney, and select the 'Transplant by donor type' report link)

- ^ Kiser, Kim (August 2010). "More than Friends and Followers: Facebook, Twitter, and other forms of social media are connecting organ recipients with donors". Minnesota Medicine. Retrieved 2014-10-17.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "To Share or Not to Share on Social Media". The Ricki Lake Show. Season 1. Episode 19. 4 October 2014. Event occurs at 29:40. 20th Television. Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- ^ Rees M. A., Kopke J. E., Pelletier R. P., Segev D. L., Rutter M. E., Fabrega A. J.; et al. (2009). "A nonsimultaneous, extended, altruistic-donor chain". The New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (11): 1096–1101. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0803645.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Montgomery R. A., Gentry S. E., Marks W. H., Warren D. S., Hiller J., Houp J.; et al. (2006). "Domino paired kidney donation: a strategy to make best use of live non-directed donation". Lancet. 368 (9533): 419–421. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69115-0.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Butt F. K., Gritsch H. A., Schulam P., Danovitch G. M., Wilkinson A., Del Pizzo J.; et al. (2009). "Asynchronous, Out-of-Sequence, Transcontinental Chain Kidney Transplantation: A Novel Concept". American Journal of Transplantation. 9 (9): 2180–2185. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02730.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sack, Kevin. "60 Lives, 30 Kidneys, All Linked." The New York Times. 19 Feb. 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/19/health/lives-forever-linked-through-kidney-transplant-chain-124.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0. 22 Oct 2013.

- ^ Ibrahim, H. N.; Foley, R; Tan, L; Rogers, T; Bailey, RF; Guo, H; Gross, CR; Matas, AJ (2009). "Long-Term Consequences of Kidney Donation". N Engl J Med. 360 (5): 459–46. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0804883. PMC 3559132. PMID 19179315.

- ^ Garg, Amit X.; Nevis, Immaculate F.; McArthur, Eric; Sontrop, Jessica M.; Koval, John J.; Lam, Ngan N.; Hildebrand, Ainslie M.; Reese, Peter P.; Storsley, Leroy; Gill, John S.; Segev, Dorry L.; Habbous, Steven; Bugeja, Ann; Knoll, Greg A.; Dipchand, Christine; Monroy-Cuadros, Mauricio; Lentine, Krista L. (2014). "Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia in Living Kidney Donors". New England Journal of Medicine. 372: 141114133004008. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1408932. ISSN 0028-4793.

- ^ "Kidney Transplant". National Health Service. 29 March 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ New Robot Technology Eases Kidney Transplants, CBS News, June 22, 2009 – accessed July 8, 2009

- ^ "Kidney and Pancreas Transplant Center – ABO Incompatibility". Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- ^ a b Jordan SC, Tyan D, Stablein D, et al. (December 2004). "Evaluation of intravenous immunoglobulin as an agent to lower allosensitization and improve transplantation in highly sensitized adult patients with end-stage renal disease: report of the NIH IG02 trial". J Am Soc Nephrol. 15 (12): 3256–62. doi:10.1097/01.ASN.0000145878.92906.9F. PMID 15579530.

- ^ "Donor kidney removed via vagina". BBC News. 2009-02-03. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- ^ "Surgeons remove healthy kidney through donor's vagina - CNN.com". cnn.com. 2009-02-03. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- ^ Rohter, Larry (May 23, 2004). "The Organ Trade – A Global Black Market – Tracking the Sale of a Kidney On a Path of Poverty and Hope". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-12-19.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/3041363.stm Call to legalise live organ trade

- ^ The Meat Market, The Wall Street Journal, Jan. 8, 2010.

- ^ Martinez, Edecio (July 27, 2009). "Black Market Kidneys, $160,000 a Pop". CBS News. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Psst, wanna buy a kidney?". Organ transplants. The Economist Newspaper Limited 2011. November 16, 2006. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ Schall, John A. (May 2008). "A New Outlook on Compensated Kidney Donations". RENALIFE. American Association of Kidney Patients. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ Gary S. Becker, Julio Jorge Elías. "Introducing Incentives in the Market for Live and Cadaveric Organ Donations" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Live donors to get financial support, RASHIDA YOSUFZAI, AAP, APRIL 07, 2013

- ^ "Singapore legalises compensation payments to kidney donors". BMJ. 337: a2456. 2008. doi:10.1136/bmj.a2456.

- ^ "Overcoming Antibody Barriers to Kidney Transplant". discoverysedge.mayo.edu. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ^ David E. R. Sutherland, Rainer W. G. Gruessner, David L. Dunn, Arthur J. Matas, Abhinav Humar, Raja Kandaswamy, S. Michael Mauer, William R. Kennedy, Frederick C. Goetz, R. Paul Robertson, Angelika C. Gruessner, John S. Najarian (April 2001). "Lessons Learned From More Than 1,000 Pancreas Transplants at a Single Institution". Ann. Surg. 233 (4). NCBI, NLM, NIH: 463–501. doi:10.1097/00000658-200104000-00003. PMC 1421277. PMID 11303130.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Kidney transplant: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". National Institutes of Health. June 22, 2009. Retrieved 2010-12-19.

- ^ Nankivell, B (2011). "Diagnosis and prevention of chronic kidney allograft loss". Lancet. 378: 1428–37. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60699-5. PMID 22000139.

- ^ a b Naesens (2015). "Proteinuria as a Noninvasive Marker for Renal Allograft Histology and Failure: An Observational Cohort Study". J Am Soc Nephrol. doi:10.1681/ASN.2015010062. PMID 26152270.

- ^ "Transplant Medication Questions". Piedmont Hospital. May 13, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-05.

- ^ "Kidney transplant". www.webmd.com. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ^ a b c d Renal Transplants > Renal Transplantation Complications from eMedicine. Author: Mert Erogul, MD; Chief Editor: Erik D Schraga, MD. Updated: Dec 5, 2008

- ^ McDonald SP, Russ GR (2002). "Survival of recipients of cadaveric kidney transplants compared with those receiving dialysis treatment in Australia and New Zealand, 1991–2001". Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 17 (12): 2212–9. doi:10.1093/ndt/17.12.2212. PMID 12454235.

- ^ Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, et al. (1999). "Comparison of Mortality in All Patients on Dialysis, Patients on Dialysis Awaiting Transplantation, and Recipients of a First Cadaveric Transplant". NEJM. 341: 1725–1730. doi:10.1056/nejm199912023412303.

- ^ Naesens, M (2014). "The Histology of Kidney Transplant Failure: A Long-Term Follow-Up Study". Transplantation. 98 (4): 427–435. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000000183. PMID 25243513.

- ^ "Facts and FAQs". Canada's National Organ and Tissue Information Site. Health Canada. 16 July 2002. Archived from the original on 2005-04-04. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ a b c d "European Activity Comparison 2003" (gif). UK Transplant. March 2004. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ "Kidney Transplantation Factbook 2011"

- ^ "National Data Reports". The Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (OPTN). Retrieved 2009-05-07. (the link is to a query interface; Choose Category = Transplant, Organ = Kidney, and select the 'Transplant by donor type' report link)

- ^ Official Website of Sindh Institute of Urology & Transplant

- ^ http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/chicoer/obituary.aspx?n=Robert-Allen-Perry&pid=174998823.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Alexander, G. C.; Sehgal, A. R. (1998). "Barriers to Cadaveric Renal Transplantation Among Blacks, Women, and the Poor". Journal of the American Medical Association. 280 (13): 1148–1152. doi:10.1001/jama.280.13.1148. PMID 9777814.

- ^ "Questions & Answers for Transplant Candidates about Multiple Listing and Waiting Time Transfer" (PDF). United Network for Organ Sharing. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ^ Sommer Gentry (2013). "Addressing Geographic Disparities in Organ Availability" (PDF). Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ^ Leamanczyk, Lauren (Nov 29, 2014). "I-Team: Professor Helps Organ Transplant Patients On Multiple Waiting Lists". WBZ-TV. Retrieved Nov 30, 2014.

- ^ Ubel, P. A. (2014). "Transplantation Traffic — Geography as Destiny for Transplant Candidates". New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (26): 2450–2452. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1407639.

- ^ "Consumerist Responses to Scarcity of Organs for Transplant". Virtual Mentor. 15 (11): 966–972. 2013. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2013.15.11.pfor2-1311.