Kirlian photography

Kirlian photography is a collection of photographic techniques used to capture the phenomenon of electrical coronal discharges. It is named after Semyon Kirlian, who in 1939 accidentally discovered that if an object on a photographic plate is connected to a high-voltage source, an image is produced on the photographic plate.[1] The technique has been variously known as "electrography",[2] "electrophotography",[3] "corona discharge photography" (CDP),[4] "bioelectrography",[5] "gas discharge visualization (GDV)",[6] "electrophotonic imaging (EPI)",[7] and, in Russian literature, "Kirlianography".

Kirlian photography has been the subject of mainstream scientific research, parapsychology research and art. To a large extent, It has been used in alternative medicine research.[8]

History

In 1889, Czech B. Navratil coined the word "electrography". Seven years later in 1896, a French experimenter, H. Baravuc, created electrographs of hands and leaves.

In 1898, Russian engineer Yakov Narkevich-Iodko[9][note 1] demonstrated electrography at the fifth exhibition of the Russian Technical Society.

In 1939, two Czechs, S. Pratt and J. Schlemmer published photographs showing a glow around leaves. The same year, Russian electrical engineer Semyon Kirlian and his wife Valentina developed Kirlian photography after observing a patient in Krasnodar hospital who was receiving medical treatment from a high-frequency electrical generator. They had noticed that when the electrodes were brought near the patient's skin, there was a glow similar to that of a neon discharge tube.[10]

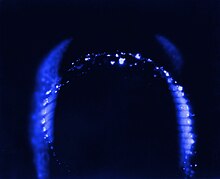

The Kirlians conducted experiments in which photographic film was placed on top of a conducting plate, and another conductor was attached to a hand, a leaf or other plant material. The conductors were energized by a high-frequency high-voltage power source, producing photographic images typically showing a silhouette of the object surrounded by an aura of light.

In 1958, the Kirlians reported the results of their experiments for the first time. Their work was virtually unknown until 1970, when two Americans, Lynn Schroeder and Sheila Ostrander, published a book Psychic Discoveries Behind the Iron Curtain. High-voltage electrophotography soon became known to the general public as Kirlian photography. Although little interest was generated among western scientists, Russians held a conference on the subject in 1972 at Kazakh State University.[11]

Kirlian photography was used in the former Eastern Bloc in the 1970s. The corona discharge glow at the surface of an object subjected to a high-voltage electrical field was referred to as a "Kirlian aura" in Russia and Eastern Europe.[12][13] In 1975, Belarusian scientist Victor Adamenko wrote a dissertation titled Research of the structure of High-frequency electric discharge (Kirlian effect) images.[14][15] Scientific study of what the researchers called the Kirlian effect was conducted by Victor Inyushin at Kazakh State University.[16][17]

Early in the 1970s, Thelma Moss and Kendall Johnson at the Center for Health Sciences at the UCLA conducted extensive research[11] into Kirlian photography. Moss led an independent and unsupported parapsychology laboratory[18] that was shut down by the university in 1979.[19]

Overview

Kirlian photography is a technique for creating contact print photographs using high voltage. The process entails placing sheet photographic film on top of a metal discharge plate. The object to be photographed is then placed directly on top of the film. High voltage is momentarily applied to the metal plate, thus creating an exposure. The corona discharge between the object and the high-voltage plate is captured by the film. The developed film results in a Kirlian photograph of the object.

Color photographic film is calibrated to produce faithful colors when exposed to normal light. Corona discharges can interact with minute variations in the different layers of dye used in the film, resulting in a wide variety of colors depending on the local intensity of the discharge.[4] Film and digital imaging techniques also record light produced by photons emitted during corona discharge (see Mechanism of corona discharge).

Photographs of inanimate objects such as a coins, keys and leaves can be made more effectively by grounding the object to the earth, a cold water pipe or to the opposite (polarity) side of the high-voltage source. Grounding the object creates a stronger corona discharge.[20]

Kirlian photography does not require the use of a camera or a lens because it is a contact print process. It is possible to use a transparent electrode in place of the high-voltage discharge plate, allowing one to capture the resulting corona discharge with a standard photo or video camera.[21]

Visual artists such as Robert Buelteman,[22] Ted Hiebert,[23] and Dick Lane[24] have used Kirlian photography to produce artistic images of a variety of subjects. Photographer Mark D. Roberts, who has worked with Kirlian imagery for over 40 years, published a portfolio of plant images entitled "Vita occulta plantarum" or "The Secret Life of Plants", first exhibited in 2012 at the Bakken Museum in Minneapolis.

Research

Kirlian photography has been a subject of scientific research, parapsychology research and pseudoscientific claims.[8][25]

Scientific research

Results of scientific experiments published in 1976 involving Kirlian photography of living tissue (human finger tips) showed that most of the variations in corona discharge streamer length, density, curvature and color can be accounted for by the moisture content on the surface of and within the living tissue.[26] Scientists outside of the US have also conducted scientific research.

Konstantin Korotkov developed a technique similar to Kirlian photography called "gas discharge visualization" (GDV).[27][28][29] Korotkov's GDV camera system consists of hardware and software to directly record, process and interpret GDV images with a computer. The web site of Korotkov promotes his device and research in a medical context.[30][31] Izabela Ciesielska at the Institute of Architecture of Textiles in Poland used Korotkov's GDV camera to evaluate the effects of human contact with various textiles on biological factors such as heart rate and blood pressure, as well as corona discharge images. The experiments captured corona discharge images of subjects fingertips while the subjects wore sleeves of various natural and synthetic materials on their forearms. The results failed to establish a relationship between human contact with the textiles and the corona discharge images and were considered inconclusive.[9]

Parapsychology research

Around the 1970s, interest in paranormal research peaked. In 1968, Dr. Thelma Moss, a psychology professor, headed UCLA's Neuropsychiatric Institute (NPI), which was later renamed the Semel Institute. The NPI had a laboratory dedicated to parapsychology research and staffed mostly with volunteers. The lab was unfunded, unsanctioned and eventually shut down by the university. Toward the end of her tenure at UCLA, Moss became interested in Kirlian photography, a technique that supposedly measured the "auras" of a living being. According to Kerry Gaynor, one of her former research assistants, "many felt Kirlian photography's effects were just a natural occurrence".[19]

Paranormal claims of Kirlian photography have not been observed or replicated in experiment by the scientific community.[32][33] The physiologist Gordon Stein has written that Kirlian photography is a hoax that has "nothing to do with health, vitality, or mood of a subject photographed."[34]

Claims

Kirlian believed that images created by Kirlian photography might depict a conjectural energy field, or aura, thought, by some, to surround living things. Kirlian and his wife were convinced that their images showed a life force or energy field that reflected the physical and emotional states of their living subjects. They thought that these images could be used to diagnose illnesses. In 1961, they published their first article on the subject in the Russian Journal of Scientific and Applied Photography.[35] Kirlian's claims were embraced by energy treatments practitioners.[36]

Torn leaf experiment

A typical demonstration used as evidence for the existence of these energy fields involved taking Kirlian photographs of a picked leaf at set intervals. The gradual withering of the leaf was thought to correspond with a decline in the strength of the aura. In some experiments, if a section of a leaf was torn away after the first photograph, a faint image of the missing section would sometimes remain when a second photograph was taken. If the imaging surface is cleaned of contaminants and residual moisture before the second image is taken, then no image of the missing section will appear.[37]

The living aura theory is at least partially repudiated by demonstrating that leaf moisture content has a pronounced effect on the electric discharge coronas; more moisture creates larger corona discharges.[4] As the leaf dehydrates, the coronas will naturally decrease in variability and intensity. As a result, the changing water content of the leaf can affect the so-called Kirlian aura. Kirlian's experiments did not provide evidence for an energy field other than the electric fields produced by chemical processes and the streaming process of coronal discharges.[4]

The coronal discharges identified as Kirlian auras are the result of stochastic electric ionization processes and are greatly affected by many factors, including the voltage and frequency of the stimulus, the pressure with which a person or object touches the imaging surface, the local humidity around the object being imaged, how well grounded the person or object is, and other local factors affecting the conductivity of the person or object being imaged. Oils, sweat, bacteria, and other ionizing contaminants found on living tissues can also affect the resulting images.[38][39][40]

Qi

Scientists such as Beverly Rubik have explored the idea of a human biofield using Kirlian photography research, attempting to explain the Chinese discipline of Qigong. Qigong teaches that there is a vitalistic energy called qi (or chi) that permeates all living things. The idea of qi as its own sort of field, not simply a creature's electromagnetic field, has been mostly disregarded by the scientific community.[citation needed]

Rubik's experiments relied on Konstantin Korotkov's GDV device to produce images, which were thought to visualize these qi biofields in chronically ill patients. Rubik acknowledges that the small sample size in her experiments "was too small to permit a meaningful statistical analysis".[41] Claims that these energies can be captured by special photographic equipment are criticized by skeptics.[36]

In popular culture

Kirlian photography has appeared as a fictional element in numerous books, films, television series, and media productions, including the 1975 film The Kirlian Force (re-released under the more sensational title Psychic Killer. Kirlian photographs have been used as visual components in various media, such as the sleeve of George Harrison's 1973 album Living in the Material World, which features Kirlian photographs of his hand holding a Hindi medallion on the front sleeve and American coins on the back, shot at Thelma Moss's UCLA parapsychology laboratory.[42]

See also

- Timeline of Russian innovation

- Bioelectromagnetism

- L-field

- Magnetic particle inspection (Magnaflux)

- Walter Kilner

- List of topics characterized as pseudoscience

Notes

- ^ Alternatively transliterated Narkevich-Yodko. It is spelled Narkevich-Todko in some sources; In Russian: Наркевич-Йодко. Some sources state that he was Polish, rendering his name Jacob Jodko-Narkiewicz

References

- ^ Julie McCarron-Benson in Skeptical - a Handbook of Pseudoscience and the Paranormal, ed Donald Laycock, David Vernon, Colin Groves, Simon Brown, Imagecraft, Canberra, 1989, ISBN 0-7316-5794-2, p11

- ^ Konikiewicz, Leonard W. (1978). Introduction to electrography: A handbook for prospective researchers of the Kirlian effect in biomedicine. Leonard's Associates.

- ^ Lane, Earle (1975). Electrophotography. And/Or Press (San Francisco).

- ^ a b c d Boyers, David G.; Tiller, William A. (1973). "Corona discharge photography". Journal of Applied Physics. 44 (7): 3102–3112. doi:10.1063/1.1662715.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Konikiewicz, Leonard W. and Griff, Leonard C. (1984). Bioelectrography, a new method for detecting cancer and monitoring body physiology. Leonard Associates Press (Harrisburg, PA).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bankovskii, N. G.; Korotkov, K. G.; Petrov, N. N. (Apr 1986). "Physical processes of image formation during gas-discharge visualization (the Kirlian effect) (Review)". Radiotekhnika i Elektronika. 31: 625–643. Bibcode:1986RaEl...31..625B.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wisneski, Leonard A.; Anderson, Lucy (2010). The Scientific Basis of Integrative Medicine. ISBN 978-1-4200-8290-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Stenger, Victor J. (1999). "Bioenergetic Fields". The Scientific Review of Alternative Medicine. 3 (1).

- ^ a b Ciesielska, Izabela L. (March 2009). "Images of Corona Discharges as a Source of Information About the Influence of Textiles on Humans" (PDF). AUTEX Research Journal. 9 (1). Lodz, Poland. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ Kirlian, S. D. (1949) Method for Receiving Photographic Pictures of Different Types of Objects, Patent, N106401 USSR.

- ^ a b Richard Cavendish, ed. (1994). Man, Myth and Magic. Vol. 11. New York, NY: Marshall Cavendish. p. 1481. ISBN 1-85435-731-X.

- ^ Antonov, A., Yuskesselieva, L. (1985) Selective High Frequency Discharge (Kirlian effect), Acta Hydrophysica, Berlin, p. 29.

- ^ Juravlev, A. E. (1966) Living Luminescence and Kirlian effect, Academy of Science in USSR.

- ^ Adamenko, V. G. (1972) Objects Moved at a Distance by Means of a Controlled Bioelectric Field, In Abstracts,International Congress of Psychology, Tokyo.

- ^ Kulin, E. T. (1980) Bioelectrical Effects, Science and Technology, Minsk.

- ^ Petrosyan, V., I., et al. (1996) Bioelectrical Discharge, Biomedical Radio-Engineering and Electronics, №3.

- ^ Inyushin, V. M., Gritsenko, V. S. (1968) The Biological Essence of Kirlian effect, Alma Ata, Kazakhstan, State University.

- ^ Thelma Moss, The Body Electric, New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher Inc., 1979.

- ^ a b Greene, Sean (27 October 2010). "UCLA lab researched parapsychology in the '70s". News, A Closer Look. UCLA Daily Bruin. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ Iovine, John (June 2000). "Kirlian Photography, Part Deux". Poptronics (16): 20.

- ^ Iovine, John (May 2000). "Kirlian Photography: Part 1". Poptronics (15): 15.

- ^ "Photographer Robert Buelteman Shocks Flowers With 80,000 Volts Of Electricity". Huffington Post. 23 July 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ Blennerhassett, Patrick (9 March 2009). "Electrifying photography". Victoria News.

- ^ Puente, Veronica (9 March 2009). "Photographer Dick Lane gets really charged up about his work". Fort Worth Star-Telegram.

- ^ Skrabanek, P. (1988). "Paranormal Health Claims". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 44 (4): 303–309. doi:10.1007/bf01961267. PMID 2834214.

- ^ Pehek, John O.; Kyler, Harry J.; Faust, David L. (15 October 1976). "Image Modulatic Corona Discharge Photography". Science. 194 (4262): 263–270. doi:10.1126/science.968480.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Korotkov K.G., Krizhanovsky E.V. et al. (2004) The Dynamic of the Gas Discharge around Drops of Liquids. In book: Measuring Energy Fields: State of the Science, Backbone Publ.Co., Fair Lawn, USA, pp. 103–123.

- ^ Korotkov K., Korotkin D. (2001) Concentration Dependence of Gas Discharge around Drops of Inorganic Electrolytes, Journal of Applied Physics, 89, 9, pp. 4732–4737.

- ^ Korotkov K. G., Kaariainen P. (1998) GDV Applied for the Study of a Physical Stress in Sportsmens, Journal of Pathophysiology, Vol. 5., p. 53, Saint Petersburg.

- ^ Katorgin, V. S., Meizerov, E. E. (2000) Actual Questions GDV in Medical Activity, Congress Traditional Medicine, Federal Scientific Clinical and Experimental Center of Traditional Methods of Treatment and Diagnosis, Ministry of Health, pp 452–456, Elista, Moscow, Russia.

- ^ Korotkov, Konstantin. "EPC/GDV CAMERA by Dr. Korotkov". Retrieved 27 August 2012.

GDV CAMERA by Dr. Korotkov provides non-invasive, painless and almost immediate evaluation which can highlight potential health abnormalities prior to even the earliest symptoms of an underlying condition, and suggests courses of action

- ^ Singer, Barry. (1981). Kirlian Photography. In George O. Abell, Barry Singer. Science and the Paranormal. pp. 196-208. ISBN 978-0862450373

- ^ Watkins, Arleen J; Bickell, William S. (1986). A Study of the Kirlian Effect. Skeptical Inquirer 10: 244-257.

- ^ Stein, Gordon. (1993). Encyclopedia of Hoaxes. Gale Group. p. 183. ISBN 0-8103-8414-0

- ^ Pilkington, Mark (5 February 2004). "The Guardian: Life: Far out: Bodies of light". The Guardian. London.

Over several years, Kirlian and his journalist wife Valentina developed equipment that allowed them to view moving objects in real time, creating dazzling visual effects. Encouraged by visits from scientific dignitaries, the Kirlians became convinced that their bioluminescent images showed a life force or energy field that reflected the physical and emotional states of their living subjects, and could even diagnose illnesses. In 1961 they published their first paper, in the Russian Journal of Scientific and Applied Photography, and their story then reached the west via the 1970 book Psychic Discoveries Behind the Iron Curtain.

- ^ a b Smith, Jonathan C. (2009). Pseudoscience and Extraordinary Claims of the Paranormal: A Critical Thinker's Toolkit. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 283. ISBN 978-1-4051-8122-8.

- ^ "Kirlian photography". An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural. James Randi Educational Foundation. Retrieved 2008-10-14., derived from:

*Randi, James (1997). An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-15119-5. - ^ Opalinski, John, "Kirlian‐type images and the transport of thin‐film materials in high‐voltage corona discharges", Journal of Applied Physics, Vol 50, Issue 1, pp 498–504, Jan 1979. Abstract: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpl/articleDetails.jsp?arnumber=5105453

- ^ The Kirlian Technique: Controlling the Wild Cards. The Kirlian effect not only is explainable by natural processes; it also varies according to at least six physical parameters. Arleen J. Watkins and Williams S. Bickel, The Skeptical Inquirer 13:172-184, 1989.

- ^ Carroll, Robert Todd (2003). The Skeptic's Dictionary: A Collection of Strange Beliefs, Amusing Deceptions, and Dangerous Delusions. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons. p. 446. ISBN 978-0-471-27242-7.

- ^ Rubik, Beverly. "The human biofield and a pilot study of qigong" (PDF). Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ Tillery, G. Working Class Mystic: A Spiritual Biography of George Harrison (2011)

Further reading

- Becker, Robert and Selden, Gary, The Body Electric:Electromagnetism and the Foundation of Life, (Quill/Williams Morrow, 1985)

- Krippner, S. and Rubin, D., Galaxies of Life, (Gordon and Breach, 1973)

- Ostrander, S. and Schroeder, L., Psi Discoveries Behind the Iron Curtain, (Prentice-Hall 1970)

- Iovine, John Kirlian Photography - A Hands on Guide , (McGraw-Hill 1993)

External links

- Kirlian Photography and the "Aura", Dr. Rory Coker, Professor of Physics at the University of Texas at Austin

- Bioenergetic Fields, Victor J. Stenger, University of Hawaii at Manoa

- Dr. Ignatov's methodic for Color Coronal (Kirlian) spectral analysis, Sofia, Bulgaria

- Kirlian Effect in the Study of the Properties of Water, Oleg Mosin, Doctor in Chemistry