Montreal Cognitive Assessment

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment | |

|---|---|

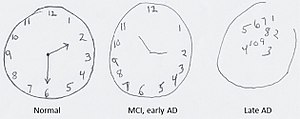

In the Montreal test, the participant is requested to draw a clock. This participant displays signs of allochiria. | |

| Synonyms | Montreal test |

| Purpose | Evaluation of cognitive deficit and Alzheimer's disease |

| Test of | Cognitive skill |

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is a widely used screening assessment for detecting cognitive impairment.[1] It was created in 1996 by Ziad Nasreddine in Montreal, Quebec. It was validated in the setting of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and has subsequently been adopted in numerous other clinical settings. This test consists of 30 points and takes 10 minutes for the individual to complete. The original English version is performed in seven steps, which may change in some countries dependent on education and culture. The basics of this test include short-term memory, executive function, attention, focus, and more.

Format

[edit]The MoCA is a one-page 30-point test administered in approximately 10 minutes.[2] The test and administration instructions are available for clinicians online. The test is available in 46 languages and dialects (as of 2017).

The MoCA assesses several cognitive domains:

- The short-term memory recall task (5 points) involves two learning trials of five nouns and delayed recall after approximately five minutes.

- Visuospatial abilities are assessed using a clock-drawing task (3 points) and a three-dimensional cube copy (1 point).

- Multiple aspects of executive function are assessed using an alternation task adapted from the trail-making B task (1 point), a phonemic fluency task (1 point), and a two-item verbal abstraction task (2 points).

- Attention, concentration, and working memory are evaluated using a sustained attention task (target detection using tapping; 1 point), a serial subtraction task (3 points), and digits forward and backward (1 point each).

- Language is assessed using a three-item confrontation naming task with low-familiarity animals (lion, camel, rhinoceros; 3 points), repetition of two syntactically complex sentences (2 points), and the aforementioned fluency task.

- Abstract reasoning is assessed using a describe-the-similarity task with 2 points being available.

- Finally, orientation to time and place is evaluated by asking the subject for the date and the city in which the test is occurring (6 points).

Because MoCA is English-specific, linguistic and cultural translations are made in order to adapt the test in other countries. Multiple cultural and linguistic variables may affect the norms of the MoCA across different countries and languages, e.g. Swedish.[3] Several cut-off scores have been suggested across different languages to compensate for the education level of the population, and several modifications were also necessary to accommodate certain linguistic and cultural differences across different languages or countries; however, not all versions have been validated.

Efficacy

[edit]MoCA test study

[edit]A MoCA test validation study by Nasreddine in 2005 showed that the MoCA was a promising tool for detecting MCI and early Alzheimer's disease compared with the well-known Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).[1]

According to the validation study, the sensitivity and specificity of the MoCA for detecting MCI were 90% and 87% respectively, compared with 18% and 100% respectively for the MMSE. Subsequent studies in other settings were less promising, though generally superior to the MMSE.[4][5]

Other studies have tested the MoCA on patients with Alzheimer's disease.[6][7][8]

People with hearing loss, which commonly occurs alongside dementia, score worse in the MoCA test, which could lead to a false diagnosis of dementia. Researchers have developed an adapted version of the MoCA test, which is accurate and reliable and avoids the need for people to listen and respond to questions.[9][10]

Recommendations

[edit]The National Institutes of Health and the Canadian Stroke Network recommended selected subsets of the MoCA for the detection of vascular cognitive impairment.[11]

Scoring

[edit]MoCA scores range between 0 and 30.[12] A score of 26 or over is considered to be normal. In a study, people without cognitive impairment scored an average of 27.4; people with MCI scored an average of 22.1; people with Alzheimer's disease scored an average of 16.2.[12]

In a study by Ihle-Hansen et al. (2017), of 3,413 Norwegian participants aged 63–65, of whom 47% had higher education (over 12 years), under 5% of subjects scored 30/30 with a mean MoCA score of 25.3 and 49% scoring below the suggested cut-off of 26 points, leading the authors to suggest that "the cut-off score may have been set too high to distinguish normal cognitive function from MCI".[13]

Normalization studies

[edit]In addition to a growing amount of international normative data, the Memory Index Score (MIS), which is included in the most recent test versions, is gaining increasing diagnostic importance.[14] In a Dutch regression-based normative data study, normative values have been published for both the total value of the MoCA and for the included Memory Index Score for a total of seven age cohorts between 18 and 91 years.[15]

Other applications

[edit]Since the MoCA assesses multiple cognitive domains, it can be a useful cognitive screening tool for several neurological diseases that affect younger populations, such as Parkinson's disease,[16][17][18] vascular cognitive impairment,[19][20] Huntington's disease,[21] brain metastasis, sleep behaviour disorder,[22] primary brain tumors (including high- and low-grade gliomas),[23] multiple sclerosis and other conditions such as traumatic brain injury, cognitive impairment from schizophrenia[citation needed] and heart failure. The test is also used in hospitals to determine whether patients should be allowed to live alone or with a home aide.

In American politics

[edit]Nikki Haley campaigned for the Republican presidential nomination partially on a platform plank that would have required all politicians aged 75 or older take the MoCA.[24] This proposal would have required both incumbent President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump, but not Haley, take the MoCA. Trump was given the MoCA in 2018 by then–White House physician Ronny Jackson. Trump's repeated use of the phrase "Person, woman, man, camera, TV" while describing the test became an Internet meme and went viral on social media platforms.[25] According to The Washington Post, Trump has frequently distorted or misrepresented the nature of the test.[26] Amid concerns about his age and health, Biden declined to undergo a cognitive exam, stating that he has "a cognitive test every single day" in performing his presidential duties.[27]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, Chertkow H (2005). "The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment". J Am Geriatr Soc. 53 (4): 695–699. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. PMID 15817019. S2CID 9014589.

- ^ Maust, Donovan; Cristancho, Mario; Gray, Laurie; Rushing, Susan; Tjoa, Chris; Thase, Michael E. (2012-01-01). "Psychiatric rating scales". Neurobiology of Psychiatric Disorders. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 106. pp. 227–237. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-52002-9.00013-9. ISBN 9780444520029. ISSN 0072-9752. PMID 22608624.

- ^ Borland, Emma; Nägga, Katarina; Nilsson, Peter M.; Minthon, Lennart; Nilsson, Erik D.; Palmqvist, Sebastian (2017-07-29). "The Montreal Cognitive Assessment: Normative Data from a Large Swedish Population-Based Cohort". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 59 (3): 893–901. doi:10.3233/JAD-170203. PMC 5545909. PMID 28697562.

- ^ Dong, YanHong; Sharma, Vijay Kumar; Chan, Bernard Poon-Lap; Venketasubramanian, Narayanaswamy; Teoh, Hock Luen; Seet, Raymond Chee Seong; Tanicala, Sophia; Chan, Yiong Huak; Chen, Christopher (2010-12-15). "The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is superior to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of vascular cognitive impairment after acute stroke". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 299 (1–2): 15–18. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2010.08.051. ISSN 1878-5883. PMID 20889166. S2CID 16292244.

- ^ Pinto, Tiago C. C.; Machado, Leonardo; Bulgacov, Tatiana M.; Rodrigues-Júnior, Antônio L.; Costa, Maria L. G.; Ximenes, Rosana C. C.; Sougey, Everton B. (Apr 2019). "Is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) screening superior to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer's Disease (AD) in the elderly?". International Psychogeriatrics. 31 (4): 491–504. doi:10.1017/S1041610218001370. ISSN 1741-203X. PMID 30426911. S2CID 53304937.

- ^ Fujiwara, Yoshinori; Suzuki, Hiroyuki; Yasunaga, Masashi; Sugiyama, Mika; Ijuin, Mutsuo; Sakuma, Naoko; Inagaki, Hiroki; Iwasa, Hajime; Ura, Chiaki (2010-07-01). "Brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment in older Japanese: validation of the Japanese version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment". Geriatrics & Gerontology International. 10 (3): 225–232. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2010.00585.x. ISSN 1447-0594. PMID 20141536. S2CID 25923554.

- ^ Guo, Qi-Hao; Cao, Xin-Yi; Zhou, Yan; Zhao, Qian-Hua; Ding, Ding; Hong, Zhen (2010-02-01). "Application study of quick cognitive screening test in identifying mild cognitive impairment". Neuroscience Bulletin. 26 (1): 47–54. doi:10.1007/s12264-010-0816-4. ISSN 1995-8218. PMC 5560380. PMID 20101272.

- ^ Luis, Cheryl A.; Keegan, Andrew P.; Mullan, Michael (2009-02-01). "Cross validation of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in community dwelling older adults residing in the Southeastern US". International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 24 (2): 197–201. doi:10.1002/gps.2101. ISSN 1099-1166. PMID 18850670. S2CID 39553891.

- ^ Dawes, Piers; Reeves, David; Yeung, Wai Kent; Holland, Fiona; Charalambous, Anna Pavlina; Côté, Mathieu; David, Renaud; Helmer, Catherine; Laforce, Robert; Martins, Ralph N.; Politis, Antonis; Pye, Annie; Russell, Gregor; Sheikh, Saima; Sirois, Marie-Josée (2023-05-01). "Development and validation of the Montreal cognitive assessment for people with hearing impairment ( MoCA-H )". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 71 (5): 1485–1494. doi:10.1111/jgs.18241. ISSN 0002-8614. PMID 36722180.

- ^ "How to identify dementia in people with hearing loss". NIHR Evidence. 2023-02-08.

- ^ Hachinski, Vladimir; Iadecola, Costantino; Petersen, Ron C.; Breteler, Monique M.; Nyenhuis, David L.; Black, Sandra E.; Powers, William J.; DeCarli, Charles; Merino, Jose G. (2006-09-01). "National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-Canadian Stroke Network vascular cognitive impairment harmonization standards". Stroke: A Journal of Cerebral Circulation. 37 (9): 2220–2241. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000237236.88823.47. ISSN 1524-4628. PMID 16917086.

- ^ a b "Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) Test: Scoring & Accuracy". Verywell. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ Ihle-Hansen, Håkon; Vigen, Thea; Berge, Trygve; Einvik, Gunnar; Aarsland, Dag; Rønning, Ole Morten; Thommessen, Bente; Røsjø, Helge; Tveit, Arnljot (August 2017). "Montreal Cognitive Assessment in a 63- to 65-year-old Norwegian Cohort from the General Population: Data from the Akershus Cardiac Examination 1950 Study". Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders Extra. 7 (3): 318–327. doi:10.1159/000480496. ISSN 1664-5464. PMC 5662994. PMID 29118784.

- ^ Kaur, Antarpreet; Edland, Steven D.; Peavy, Guerry M. (2018). "The MoCA-Memory Index Score: An Efficient Alternative to Paragraph Recall for the Detection of Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment". Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 32 (2): 120–124. doi:10.1097/WAD.0000000000000240. ISSN 1546-4156. PMC 5963962. PMID 29319601.

- ^ Kessels, Roy P. C.; de Vent, Nathalie R.; Bruijnen, Carolien J. W. H.; Jansen, Michelle G.; de Jonghe, Jos F. M.; Dijkstra, Boukje A. G.; Oosterman, Joukje M. (January 2022). "Regression-Based Normative Data for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and Its Memory Index Score (MoCA-MIS) for Individuals Aged 18–91". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 11 (14): 4059. doi:10.3390/jcm11144059. ISSN 2077-0383. PMC 9318507. PMID 35887823.

- ^ Dalrymple-Alford, J. C.; MacAskill, M. R.; Nakas, C. T.; Livingston, L.; Graham, C.; Crucian, G. P.; Melzer, T. R.; Kirwan, J.; Keenan, R. (2010-11-09). "The MoCA: well-suited screen for cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease". Neurology. 75 (19): 1717–1725. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fc29c9. ISSN 1526-632X. PMID 21060094. S2CID 13784144.

- ^ Kasten, Meike; Bruggemann, Norbert; Schmidt, Alexander; Klein, Christine (2010-08-03). "Validity of the MoCA and MMSE in the detection of MCI and dementia in Parkinson disease". Neurology. 75 (5): 478–479. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e7948a. ISSN 0028-3878. PMC 2788810. PMID 20679642.

- ^ Hoops, S; Nazem, S; Siderowf, A D.; Duda, J E.; Xie, S X.; Stern, M B.; Weintraub, D (2009-11-24). "Validity of the MoCA and MMSE in the detection of MCI and dementia in Parkinson disease". Neurology. 73 (21): 1738–1745. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c34b47. ISSN 0028-3878. PMC 2788810. PMID 19933974.

- ^ Cameron, Jan; Worrall-Carter, Linda; Page, Karen; Riegel, Barbara; Lo, Sing Kai; Stewart, Simon (2010-05-01). "Does cognitive impairment predict poor self-care in patients with heart failure?". European Journal of Heart Failure. 12 (5): 508–515. doi:10.1093/eurjhf/hfq042. ISSN 1879-0844. PMID 20354031.

- ^ Wong, Adrian; Xiong, Yun Y.; Kwan, Pauline W. L.; Chan, Anne Y. Y.; Lam, Wynnie W. M.; Wang, Ki; Chu, Winnie C. W.; Nyenhuis, David L.; Nasreddine, Ziad (2009-01-01). "The validity, reliability and clinical utility of the Hong Kong Montreal Cognitive Assessment (HK-MoCA) in patients with cerebral small vessel disease". Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 28 (1): 81–87. doi:10.1159/000232589. ISSN 1421-9824. PMID 19672065. S2CID 41874522.

- ^ Videnovic, Aleksandar; Bernard, Bryan; Fan, Wenqing; Jaglin, Jeana; Leurgans, Sue; Shannon, Kathleen M. (2010-02-15). "The Montreal Cognitive Assessment as a screening tool for cognitive dysfunction in Huntington's disease". Movement Disorders. 25 (3): 401–404. doi:10.1002/mds.22748. ISSN 1531-8257. PMID 20108371. S2CID 29152827.

- ^ Bertrand, Josie-Anne; Marchand, Daphné Génier; Postuma, Ronald B.; Gagnon, Jean-François (2016-07-28). "Cognitive dysfunction in rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder". Sleep and Biological Rhythms. 11 (1): 21–26. doi:10.1111/j.1479-8425.2012.00547.x. ISSN 1446-9235. S2CID 51962113.

- ^ Olson, Robert Anton; Chhanabhai, Taruna; McKenzie, Michael (2008-11-01). "Feasibility study of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in patients with brain metastases". Supportive Care in Cancer. 16 (11): 1273–1278. doi:10.1007/s00520-008-0431-3. ISSN 0941-4355. PMID 18335256. S2CID 12763827.

- ^ "What is the mental competency test Nikki Haley wants politicians over 75 to take?". Yahoo News. May 4, 2023.

- ^ Welsh, Caitlin (July 22, 2020). "Trump's latest boast about his 'very hard' cognitive test instantly became a bleakly funny meme". Mashable. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- ^ Parker, Ashley; Diamond, Dan (January 19, 2024). "A 'whale' of a tale: Trump continues to distort cognitive test he took". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- ^ Kanno-Youngs, Zolan (6 July 2024). "Biden Says He Has Not Had a Cognitive Test and Doesn't Need One". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

External links

[edit]- Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (PDF) Version 8.1 English