New Amsterdam

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2007) |

| New Netherland series |

|---|

| Exploration |

| Fortifications: |

| Settlements: |

| The Patroon System |

|

| People of New Netherland |

| Flushing Remonstrance |

|

New Amsterdam (Dutch: Nieuw Amsterdam) was the 17th century Dutch colonial town that later became New York City.

The town developed outside of Fort Amsterdam on Manhattan Island in the New Netherland territory (1614–1664) which was situated between 38 and 42 degrees latitude as a provincial extension of the Dutch Republic from 1624. Provincial possession of the territory was accomplished with the first settlement which was established on Governors Island in 1624. A year later, in 1625, construction of a citadel comprising Fort Amsterdam was commenced. Earlier, the harbor and the river had been discovered, explored and charted by an expedition of the Dutch East India Company captained by Henry Hudson in 1609. From 1611 through 1614, the territory was surveyed and charted by various private commercial companies on behalf of the States General of the Dutch Republic and operated for the interests of private commercial entities prior to official possession as a North American extension of the Dutch Republic in the form of an overseas province in 1624.

The town of New Amsterdam became a city when it received municipal rights in 1653 and was unilaterally reincorporated as New York City in June 1665, making it the oldest incorporated city in the United States. The town was founded in 1625 by New Netherland's second director, Willem Verhulst who, together with his council, selected Manhattan Island as the optimal place for permanent settlement by the Dutch West India Company. That year, military engineer and surveyor Cryn Fredericksz van Lobbrecht laid out a citadel with Fort Amsterdam as centerpiece. To secure the settlers' property and its surroundings according to Dutch law, the third director, Peter Minuit, created a deed with the Manhattan Indians in 1626 which officially authorized legal possession of Manhattan according to Dutch Laws.

The city, situated on the strategic, fortifiable southern tip of the island of Manhattan was to maintain New Netherland's provincial integrity by defending river access to the company's fur trade operations in the North River, later named Hudson River. Furthermore, it was entrusted to safeguard the West India Company's exclusive access to New Netherland's other two estuaries; the Delaware River and the Connecticut River. New Amsterdam developed into the largest Dutch colonial settlement in the New Netherland province, now the New York Tri-State Region, and remained a Dutch possession until August 1664, when it fell provisionally into the hands of the English.

The Dutch Republic regained it in August 1673 with a fleet of 21 ships, renaming the city "New Orange". New Netherland was ceded permanently to the English in November 1674 in the Treaty of Westminster.

The 1625 date of the founding of New Amsterdam is now commemorated in the Official Seal of the City of New York (formerly, the year on the seal was 1664, the year of the provisional Articles of Transfer, ensuring New Netherlanders that they "shall keep and enjoy the liberty of their consciences in religion", negotiated with the English by Petrus Stuyvesant and his council).

History

Early Settlement (1609–1625)

The first recorded exploration by the Dutch of the area around what is now called New York Bay was in 1609 with the voyage of the ship Halve Maen or "Half Moon", captained by Henry Hudson, in the service of the Dutch Republic, as the emissary of Holland's Lord-Lieutenant Maurits. Hudson named the river the Mauritius River and was covertly attempting to find the Northwest Passage for the Dutch East India Company. Instead, he brought back news about the possibility of exploitation of beaver pelts in the area, leading to private commercial interest by the Dutch who sent commercial, private missions to the area the following years.

At the time, beaver pelts were highly prized in Europe, because the fur could be "felted" to make waterproof hats. A by-product of the trade in beaver pelts was castoreum — the secretion of the animals' anal glands — which was used for its supposed medicinal properties. The expeditions by Adriaen Block and Hendrick Christiansz in the years 1611, 1612, 1613 and 1614 resulted in the surveying and charting of the region from the 38th parallel to the 45th parallel. On their 1614 map, which gave them a four year trade monopoly under a patent of the States General, they named the newly discovered and mapped territory New Netherland for the first time. It also showed the first year-round, top-of-the-Hudson River, island-based trading presence in New Netherland, Fort Nassau, which 10 years later, in 1624, would be replaced by Fort Orange on the main land which grew into the town of Beverwyck, now Albany.

- Main article: New Netherland.

The territory of New Netherland, comprising the Northeast's largest rivers with access to the beaver trade, was provisionally a private, profit-making commercial enterprise focusing on cementing alliances and conducting trade with the diverse Indian tribes. They enabled the serendipitous surveying and exploration of the region as a prelude to anticipated official settlement by the Dutch Republic which occurred in 1624.

Immediately after the armistice period between the Dutch Republic and Spain (1609–1621), the founding of the Dutch West India Company took place in 1621. That year, as well as in 1622 and 1623, orders were given to the private, commercial traders to vacate the territory, thus opening up the territory to the transplantation of Dutch culture onto the North American continent whereon the laws and ordinances of the states of Holland would now apply. Previously, during the private, commercial period, only the law of the ship had applied. The mouth of the Hudson River was selected as the most perfect place for initial settlement as it had easy access to the ocean while securing an ice free lifeline to the beaver-rich, unexploited forests farther north where the company's traders could be in close contact with the American Indian hunters who supplied them with pelts in exchange for European-made trade goods for barter and wampum, which was soon being "minted" under Dutch auspices on Long Island.

Thus in 1624 when the first group of families arrived on Governors Island to be followed by the second group of settlers to the island in 1625, in order to take possession of the New Netherland territory and to operate various trading posts, they were spread out to Verhulsten Island (Burlington Island) in the South River (Delaware River), to Kievitshoek (now Old Saybrook, Connecticut) at the mouth of the Verse River (Connecticut River) and at the top of the Mauritius or North River (Hudson River), now Albany.

Fort Amsterdam (1625)

The potential threat of attack from other interloping European colonial powers prompted the Directors of the Dutch West India Company to formulate a plan to protect the entrance to the Hudson River, and to consolidate the trading operations and the bulk of the settlers into the vicinity of a new fort. In 1625, most of the cattle and some settlers were moved from Noten Eylant, since 1784 named Governors Island, to Manhattan Island where a citadel to contain Fort Amsterdam was being laid out by Cryn Frederickz van Lobbrecht at the direction of Willem Verhulst who had been empowered by the Dutch West India Company to make that decision in his and his council's best judgment.

For the location of the fort, company director Willem Verhulst and Military Engineer and Surveyor Cryn Fredericks chose a site just above the southern tip of Manhattan. The new fortification was to be called Fort Amsterdam. By the end of the year 1625, the site had been staked out directly south of Bowling Green on the site of the present U.S. Custom House; west of the fort's site, later landfill has now created Battery Park.

1625–1674

Willem Verhulst, with his council responsible for the selection of Manhattan as permanent place of settlement and situating Fort Amsterdam, was replaced by Peter Minuit in 1626.

To legally safeguard the settlers' investments, possessions and farms on Manhattan island, Minuit negotiated the "purchase" of Manhattan from the Manahatta band of Lenape for 60 guilders worth of trade goods. The deed itself has not survived so the conditions causing the negotiation and validation of the deed are unknown. A textual reference to the deed became a foundation for the legend that Minuit had purchased Manhattan from the Native Americans for 24 dollars' worth of trinkets.

While the originally designed large fort, meant to contain the population as in a fortified city, was being constructed, the Mohawk–Mahican War at the top of the Hudson led the company to relocate the settlers from there to the vicinity of the new Fort Amsterdam. As the settlers were at peace with the Manahatta Indians, the fact that no large scale foreign powers were imminently trying to seize the territory, and that colonizing was a prohibitively expensive undertaking, only partly subsidized by the fur trade, led a scaling back of the original plans. By 1628, a smaller fort was constructed with walls containing a mixture of clay and sand, like in Holland. See also Wall Street.

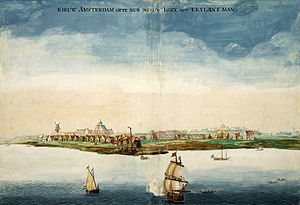

Upon first settlement on Noten Eylant (now Governors Island) in 1624, a fort and sawmill was built. The latter was constructed by Franchoys Fezard. The New Amsterdam settlement had a population of approximately 270 people, including infants. A pen-and-ink view of New Amsterdam, drawn on-the-spot and discovered in the map collection of the Austrian National Library of Vienna in 1991, provides a unique view of Nieuw Amsterdam as it appeared from Capske (small Cape) Rock in 1648. Capske Rock was situated in the water close to Manhattan between Manhattan and Noten Eylant (renamed Governors Island in 1784), which signaled the start of the East River roadstead. New Amsterdam received municipal rights on February 2, 1653 thus becoming a city. On August 22, 1654, the first Ashkenazic Jews arrived with West India Company passports from Amsterdam to be followed in September by a sizable group of Sephardic Jews, without passports, fleeing from the Portuguese reconquest of Dutch possessions in Brazil. The legal-cultural foundation of toleration as the basis for plurality in New Amsterdam superseded matters of personal intolerance or individual bigotry. Hence, and in spite of certain persons private objections (including that of director-general Peter Stuyvesant), the Sephardim were granted permanent residency on the basis of "reason and equity" in 1655. Nieuw Haarlem was formally recognized in 1658.

On August 27, 1664, in a surprise incursion when England and the Dutch Republic were at peace, four English frigates sailed in New Amsterdam’s harbor and demanded New Netherland’s surrender, whereupon New Netherland was provisionally ceded by director-general Peter Stuyvesant. This resulted in the Second Anglo-Dutch War, between England and the United Netherlands.

In 1667, the Dutch did not press their claims on New Netherland (but did not relinquish them either) in the Treaty of Breda, in return for an exchange with the tiny Island of Run in North Maluku, rich in nutmegs and the guarantee for the factual possession of Suriname, that year captured by them. The New Amsterdam city was subsequently renamed New York, after the Duke of York (later King James II) — brother of the English King Charles II — who had been granted the lands with the kingly stroke of an armchair pen (similar to the Spanish claim to the entire western hemisphere).

However, in the Third Anglo-Dutch War, the Dutch recaptured New Netherland in August 1673 and installed Anthony Colve as New Netherland's first Governor (previously there had only been West India Company Directors), and the city was renamed "New Orange". After the signing of the Treaty of Westminster in November 1674 the city was relinquished to British rule and the name reverted to "New York"; Suriname became an official Dutch possession in return.

Maps of New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam's beginnings, unlike most other colonies in the New World, were thoroughly documented in maps. During the time of New Netherland's colonization the Dutch were Europe's pre-eminent cartographers. Moreover, as the Dutch West India Company's delegated authority over New Netherland was threefold, maintaining sovereignty on behalf of the States General, generating cash flow through commercial enterprise for its shareholders and funding the province's growth, its directors regularly required that censuses be taken. These tools to measure and monitor the province's progress were accompanied by accurate maps and plans. These surveys, as well as grassroots activities to seek redress of grievances, account for the existence of some of the most important of the early documents[1].

There is a particularly detailed map called the Castello Plan. Virtually every structure in New Amsterdam at the time is believed to be represented, and by a fortunate coincidence it can be determined who resided in every house from the Nicasius de Sille List of 1660, which enumerates all the citizens of New Amsterdam and their addresses[2].

The map known as the Duke's Plan probably derived from the same 1660 census as the Castello Plan. The Duke's Plan includes the earliest suburban development on Manhattan (the two outlined areas along the top of the plan). The work was created for James (1633-1701), the duke of York and Albany, after whom New York City and New York State's capital Albany was named, just after the seizure of New Amsterdam by the British[3]. After that provisional relinquishment of New Netherland, Stuyvesant reported to his superiors that he "had endeavored to promote the increase of population, agriculture and commerce...the flourishing condition which might have been more flourishing if the now afflicted inhabitants had been protected by a suitable garrison...and had been helped with the long sought for settlement of the boundary, or in default thereof had they been seconded with the oft besought reinforcement of men and ships against the continual troubles, threats, encroachments and invasions of the English neighbors and government of Hartford Colony, our too powerful enemies."

The existence of these maps has proven to be very useful in the archaeology of New York. For instance, the excavation of the Stadthuys (City Hall) of New Amsterdam had great help in finding the exact location of the building from the Castello map[4].

See also

| History of New York City |

|---|

|

Lenape and New Netherland, to 1664 New Amsterdam British and Revolution, 1665–1783 Federal and early American, 1784–1854 Tammany and Consolidation, 1855–1897 (Civil War, 1861–1865) Early 20th century, 1898–1945 Post–World War II, 1946–1977 Modern and post-9/11, 1978–present |

| See also |

|

Transportation Timelines: NYC • Bronx • Brooklyn • Queens • Staten Island Category |

External links

- New Amsterdam from the New Netherland Project

- The New Amsterdam Project on Governors Island

- New York's Legacy, New York's Identity (19-page article)

- New York and its origins

- Origin of American Toleration, Center of American Pluralism, Lifeblood of American Liberty (34 slides)

- From Van der Donck to Visscher: a 1648 view of New Amsterdam, discovered in Vienna in 1991

- Background on the Native Americans of the area

- New Amsterdam on the Dutch Wikipedia

References

- ^ Robert Augustyn, "Maps in the making of Manhattan" Magazine Antiques, September 1995. URL accessed on December 15, 2005.

- ^ Several repreductions of the Castello plan can be found on-line: [1], [2]. A colored version from 1916 can be found here: [3]. An interactive map (you can click on the buildings) can be found here: [4]. All URLs accessed on December 15, 2005.

- ^ An image of the Duke's map can be found on-line at the British Library site: [5]. URL accessed on December 15, 2005.

- ^ A slideshow of the famous Stadt Huys dig, a landmark archaeological excavation of one of the central blocks of New Amsterdam, can be found here: [6]. A 17-century picture of the Stadthuys can be found here: [7]. Both URLs accessed on December 15, 2005.

- Hugh Morrison, Early American Architecture ISBN 0-486-25492-5 (Oxford University Press, 1952) [Dover Ed. 1987]

- Russell Shorto, The Island at the Center of the World, The Epic Story of Dutch Manhattan and the Forgotten Colony That Shaped America ISBN 0-385-50349-0 (New York, Doubleday, 2004)