Kingdom of Norway (1814)

Kingdom of Norway Kongeriget Norge | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1814 | |||||||||

| Motto: Enig og tro til Dovre faller "United and loyal until the mountains of Dovre crumble" Royal motto Gud og fædrelandet "God and the fatherland" | |||||||||

| Anthem: Norges Skaal "Norway’s Toast" | |||||||||

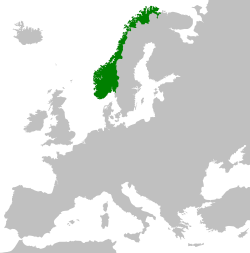

The Kingdom of Norway in 1814. | |||||||||

| Capital | Christiania | ||||||||

| Common languages | Norwegian, Danish, Western Sami languages | ||||||||

| Religion | Lutheranism | ||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• 1814 | Christian Frederick | ||||||||

| First Minister | |||||||||

• 1814 | Frederik Gottschalk von Haxthausen | ||||||||

| Legislature | Storting | ||||||||

| Lagting | |||||||||

| Odelsting | |||||||||

| Historical era | Napoleonic Wars | ||||||||

| 14 January 1814 | |||||||||

| 16 February 1814 | |||||||||

| 17 May 1814 | |||||||||

| 26 July 1814 | |||||||||

| 14 August 1814 | |||||||||

| 4 November 1814 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1814 | 324,220 km2 (125,180 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1814[1] | 902,100 | ||||||||

| Currency | Rigsdaler | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | NO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

1814 was a pivotal year in the history of Norway. It started with Norway in a union with Denmark subject to a naval blockade being ceded to the king of Sweden. In May a constitutional convention declared Norway independent. By the end of the year the Norwegian parliament had agreed to join with Sweden in a personal union under the monarch of Sweden. Although nationalist aspirations were not to be fully realized until the events of 1905, 1814 was the crisis and turning point in events that would lead to a fully independent Norway.

The year contains the story of one king and two ambitious future kings in Scandinavia who may have hoped to unite Sweden, Denmark, and Norway under their throne.[2][3] The Norwegian people and their leaders were caught in the middle of this rivalry, attempting through the crisis to create a measure of self-determination.[4]

Prior to 1814

Denmark–Norway had become entangled on the French side in the Napoleonic War through its participation in the Gunboat War. Having lost its fleet, it was virtually defenceless as the tides turned against France. The Royal Navy had blocked all Norwegian ports effectively from 1808, thus breaking many bonds to Denmark, and leaving Norway to itself. Under those conditions, tension grew in Norway, and a fledgling independence movement was formed in 1809.[citation needed] The Swedish campaign against Norway in 1808-09 had been repulsed by the Norwegian army, something that made Norwegians more prone to independence.

The years of 1812 and 1813 were known for severe famine due to the blockade, and the hardships were long remembered in Norway.

Treaty of Kiel

On January 7, 1814, about to be overrun by Swedish, Russian, and German troops under the command of the elected crown prince of Sweden, Charles John, Frederick VI of Denmark was prepared to cede Norway to the king of Sweden in order to avoid an occupation of Jutland. He authorized his envoyé Edmund Bourke (1761–1821) to negotiate a peace treaty with Sweden and Great Britain on these terms, in return for immediate withdrawal of all allied troops from Danish territory and certain territorial compensations. In addition, he was to join the allied powers in their fight against Napoleon.[5] These terms were formalized and signed at the Treaty of Kiel on January 14, in which Denmark negotiated to maintain sovereignty over the Norwegian possessions of Greenland, the Faroe Islands, and Iceland. Secret correspondence from the British government in the preceding days had put pressure on the negotiating parties to reach an agreement to avoid a full-scale invasion of Denmark. Bernadotte sent a letter to the governments of Prussia, Austria, and the United Kingdom thanking them for their support, acknowledging the role of Russia in negotiating the peace, and envisaging greater stability in the Nordic region.

These news did not reach Norway until the end of January, in a letter of 18 January from the Danish king to the Norwegian people, in which he released them from their oath of allegiance to him and his dynasty. By special courier, a secret letter of 17 January from the king was delivered on 24 January to his cousin and viceroy of Norway, Prince Christian Frederick with the most important details of the treaty, which the Prince decided to keep to himself while considering his reaction. The letter instructed him to deliver the Norwegian fortresses to Swedish forces and then return to Denmark.[6]

The public were informed of the peace treaty on 26 January through a censored article in the newspaper Tiden, under the headline. "Peace, Peace in the North!" It did not clearly convey the fact that the king had ceded his kingdom to the king of Sweden, historically the enemy of Norway.[7] As there was the annual February market in Christiania at the same time, a local priest observed that the entire marketplace swirled with rumours of the treaty, and with tension. As news spread, it was apparent to many Norwegian intellectuals that the people were offended by the treaty, by being delivered like cattle to a foreign sovereign.[8]

Attempted reclamation by Christian Frederick

The viceroy and heir to the thrones of Denmark and Norway, Prince Christian Frederick, resolved to disobey the instructions from his King and to take the lead in an insurrection to preserve the integrity of the country, and if possible the union with Denmark. The King had been informed of these plans in a secret letter of December 1813. The Prince had also been instructed to keep the union with Denmark intact, but this was not in accord with Norwegian wishes at the time. In Norway, the sentiment was that Norway had been "sold out" to Sweden, their sworn arch-enemy.

Financial problems forced the Prince on 27 January to order banknotes to the amount of 3 million Rigsbankdaler to be issued by "The Provisional Rigsbank of Norway", stamped with the Norwegian coat of arms, to be redeemed by the Rigsbank. These so-called "Prince notes" were necessary to keep the wheels of government turning, but they contributed to the already chaotic monetary situation and the galloping inflation. The cause of the financial crisis was the refusal of King Frederick VI to establish a Bank of Norway.[9]

Christian Frederick decided to claim the throne of Norway as rightful heir, and to set up an independent government with himself at the head. The week prior to January 30, the prince toured parts of Norway and found the same real or false willingness to fight everywhere he came. He soon understood that he could use this sentiment to his own advantage. On January 30, he consulted several prominent Norwegian advisors, arguing that King Frederick had no legal right to relinquish his inheritance, asserting that he was the rightful King of Norway, and that Norway had a right to self-determination. His impromptu council agreed with him, setting the stage for an independence movement. After this day, the tour continued, all the way to Trondheim and back.

On February 2, the Norwegian public learned that their country was ceded to the king of Sweden. There was growing enthusiasm for Christian Frederick's ideas for an independent Norway.

On February 8, Bernadotte responded by threatening to send an army to occupy Norway, promising a constitutional convention, and threatening a continued grain embargo against Norway if Sweden's claims under the treaty of Kiel were not met. But for the time being, he was occupied with the concluding battles on the Continent, giving the Norwegians time to develop their plans.

The independence movement solidifies and is threatened by war

On February 10, Christian Frederick invited prominent Norwegians to a meeting to be held at his friend Carsten Anker's estate in Eidsvoll to discuss the situation. He informed them of his intent to resist Swedish hegemony and claim the Norwegian crown as his inheritance. But at the emotional session in Eidsvoll on February 16, his advisors convinced him that Norway's claim to independence should rather be based on the principle of self-determination, and that he should act as a regent for the time being. The council also advised the regent to hold elections and oaths of independence all over the country, thus choosing delegates to a constitutional assembly.

Arriving in Christiania (Oslo) on February 19, Christian Frederick proclaimed himself regent of Norway. All congregations met on February 25 to swear loyalty to the cause of Norwegian independence and to elect delegates to a constitutional assembly to commence at Eidsvoll on April 10.

On February 20, the Swedish government sent a mission to Christian Frederick, warning him that Norway's independence movement was a violation of the treaty of Kiel and put Norway at war with the victorious parties in the Napoleonic War. The consequences would be famine and bankruptcy. Christian Frederick sent letters through his personal network to governments throughout Europe, assuring them that he was not leading a Danish conspiracy to reverse the terms of the treaty of Kiel, but rather his efforts reflected the Norwegian will for self-determination. He also sought a secret accommodation with Napoleon I.

The mission from the Swedish government arrived in Christiania on February 24 and met with Christian Frederick. Christian Frederick refused to accept a proclamation from the Swedish king but insisted instead on reading his letter to the Norwegian people, proclaiming himself regent. The Swedish delegation characterized his decisions as reckless and illegal, asking for leave to return to Sweden. The day after, church bells in Christiania rang for a full hour, and the city's citizens convened to swear fealty to Christian Frederick. On February 26, he initiated a long correspondence with the Swedish government. The next day he introduced a new flag for independent Norway — the former Dano-Norwegian Dannebrog with the Norwegian Lion in the canton.

February 25 is remembered in some sources as "people´s day"[citation needed] because of the elections and the oath. That day showed forth a de facto declaration of independence for Norway.[citation needed] All sources remembering that day agrees on the sacred tone of the day, when all people assembled in their churches for a common cause. Bells rang from 10 am, chiming for a full hour. 4,000 people assembled in the central church of Christiania. At 11 am the regent arrived, and a service was held. Then the bishop intoned the oath: "Do you swear to claim the independence of Norway, and to dare life and blood for the beloved fatherland?" Both the regent and the congregation answered accordingly. This oath was taken in maybe 75 churches that day, and again over the country the next Sunday, and further, until the oath was taken in all the congregations of Norway.

Carsten Anker was sent to London to negotiate recognition by the British government. Swedish authorities were canvassing border areas with pamphlets subverting the independence movement. By early March, Christian Frederick had also organized a cabinet and five government departments, though he retained all decision-making authority himself.

Christian Frederick meets increasing opposition from within and abroad

The Count of Wedel-Jarlsberg, the most prominent member of the Norwegian nobility, arrived in Norway on March 3 and confronted the regent, accusing him of playing a dangerous game. Christian Frederick responded by accusing Wedel-Jarlsberg of colluding with the Swedes. Returns from elections for delegates to the constitutional assembly also showed there were widespread misgivings about the independence movement. By the end of March, the opinion was openly expressed that Christian Frederick's ambition was to bring Norway back under Danish sovereignty.

Before Carsten Anker arrived in the UK, the British foreign secretary Robert Stewart, reimposed the naval blockade of Norway and assured the Swedish king that the British would not accept any Norwegian claims of sovereignty. A conciliatory letter sent by Christian Frederick to the Swedish king was returned unopened. On March 9, the Swedish mission to Copenhagen demanded that Christian Frederick be disinherited from succession to the Danish throne, and that European powers should go to war with Denmark unless he disassociated himself from the Norwegian independence movement. On March 17, Niels Rosenkrantz, the Danish foreign minister, responded to the Swedish demands by asserting that the Danish government in no way supported Norwegian independence, but that they could not vacate border posts they did not hold. The demand for disinheriting Christian Frederick was not addressed.

In several letters to Count Hans Henrik von Essen, the commander of the Swedish military forces at Norway's borders, Bernadotte referred to Christian Frederick as a rebel who had probably been misled by the Danish nobility. He ordered his forces to treat all Danish officials who did not return home as outlaws, and all users of the "prince dollars" to be considered counterfeiters. Swedish troops amassed along the border to Norway, and there were daily rumours of an invasion.

In spite of his open opposition to Christian Frederick, Wedel-Jarlsberg was elected as a delegate to the constitutional convention on March 14. There were clear signs that the convention, only weeks away, would be contentious.

Carsten Anker arrived in London on March 24, where he met with an under-secretary of foreign affairs. The under-secretary rejected Anker's appeal for self-determination, and Anker found all other doors closed to him in London. On April 2, Christian Frederick sent Carsten Anker's brother Peter (1744−1832) to London as an unofficial emissary. On April 3, Carsten Anker was imprisoned for three days in debtors' prison on account of an old debt, probably at the behest of the Swedish ambassador to London.

On March 31, Christian Frederick arrested officers of the naval vessels stationed in Norway as they were preparing to follow orders to bring the ships to Denmark. The ships were confiscated as ships of the Norwegian navy.

On April 1, Frederick VI sent a letter to Christian Frederick, asking him to give up his efforts and return to Denmark. The possibility of disinheriting the crown prince was mentioned in the letter. Christian Frederick rejected the overture, in the same letter invoking Norway's right to self-determination and the possibility of keeping Norway under the Danish king. A few days later, Christian Frederick warned off a meeting with the Danish foreign minister Niels Rosenkrantz, pointing out that such a meeting would fuel speculation that the prince was motivated by Danish designs on Norway.

Constituent Assembly

Although the European powers refused to acknowledge the Norwegian independence movement, there were signs by early April that they were not inclined to support Sweden in an all-out confrontation on the matter.

As time approaches for the constitutional convention, there was growing support for opposition to the treaty of Kiel, especially from Bergen.

On April 10, the constitutional convention convened for the first time, at church services in Eidsvoll. The sermon caused some stir by flattering Christian Frederick in particular and the monarchy in general. The delegates were accredited that afternoon, after Severin Løvenskiold had refused to give fealty to the independence movement.

Seated on uncomfortable benches, the convention elected its officers in the presence of Christian Frederick on April 11. The debates started on April 12, when Nicolai Wergeland and Georg Sverdrup argued over the mandate of the assembly and the basis for the regent's legitimacy. Party lines took form, with the "Independence party," variously known as the "Danish party," "the Prince's party," or "the urgent" on one side of the aisle; and the "Union Party," also known as the "western party," "Swedish party," or "the hesitant" on the other.[citation needed]

As it turned out, there was a clear consensus among all delegates that independence would be the ideal solution, but there was disagreement what solution was workable given real-world constraints.

- The Independence party had the majority and argued that the mandate of the convention was limited to formalizing Norway's independence based on the popular oath of fealty from earlier that year. With Christian Frederick as the regent, the relationship with Denmark would be negotiated within the context of Norwegian independence.

- The Union party, a minority of the delegates, believed that Norway would achieve a more independent status within a loose union with Sweden than as part of the Danish monarchy, and that the assembly should continue its work even after the constitution was complete.

A constitutional committee presented its proposals on April 16, provoking a lively debate. The Independence party won the day with a majority of 78-33 to establish Norway as an independent monarchy. There was also lively debate on the issue of military conscription, in which the upper classes argued for exemption. In the following days, mutual suspicion and distrust came to the surface within the convention. In particular, delegates disagreed on whether to give the sentiments of the European powers consideration, and some facts may have been withheld from the convention.

By April 20, the principle of the people's right to self-determination articulated by Christian Magnus Falsen and Gunder Adler had been established as foundational for the framing of the constitution. Continued work and debate was characterized by acrimony and recrimination, but the constitutional committee made steady progress.

Framing the constitution

On May 1, the first draft of the constitution was signed by the drafting committee. In addition to the principle of the Norwegian people's right to self-determination, the constitution's key precepts included the assurance of individual freedom, the right to property, and equality.

Following a contentious debate on May 4, the assembly decided that Norway would profess itself to the Lutheran-Evangelical faith, that its monarch must always have professed himself to this faith (thereby precluding the Catholic-born Bernadotte from being a king), and that Jews and Jesuits would be barred from entering the kingdom.

On May 5, the Independence party lost another battle when the assembly voted 98 to 11 to allow the kingdom's monarch to reign over another country with the assent of two thirds of the legislative assembly's vote.

On May 7, the assembly outlawed the creation of new nobility in Norway, allowing the disposition of existing hereditary rights to be decided by a future legislative body. On May 8, proposed laws concerning naturalization and suffrage were debated. On the next day, it was decided that foreign citizens would be eligible after ten years of residency, and that the right to vote would be extended to men who were either farmers possessing their own land, civil servants, or urban property owners. With this, about half of all Norwegian men earned the right to vote, a radical proposition at the time.

On May 8, the assembly decided on a bicameral legislative body to be known as the Storting, with the expectation that one would be an upper house (Lagting), and a lower house (Odelsting). They also vested the right to establish and collect taxes in the legislative body. The assembly also passed the so-called "farmer's paragraph" stipulating that two-thirds of the Storting had to be elected from rural districts, and one-third from urban areas. (This paragraph remained in force until 1952).

On May 11, the assembly overwhelmingly passed universal conscription, over the objections of the financial and administrative elite, who threatened mass emigration if their sons were forced into military service.

On May 13, after two days of debate, the assembly passed a law in which the assembly guaranteed the issue of a Norwegian currency. The Union party opposed this, claiming that there simply wasn't an economic basis for an independent currency. The Independence party, carrying the day, responded that an independent currency was necessary to ensure the existence of an independent state, regardless of the financial considerations. Nevertheless, on the next day, the assembly decided to postpone the establishment of a central bank until a legislative body was in session. Christian Frederick was dismayed by this decision.

The final edit of the constitution was approved on May 16. The official copy was dated, signed and sealed by the presidency on May 17, and signed by the other representatives on May 18. May 17 is accordingly considered Constitution Day in Norway. On that same day, Christian Frederick was elected king of Norway. The election was unanimous, but several of the delegates put on the record that they would have preferred to see it postponed until the political situation had stabilized.

After the election, Georg Sverdrup, then president of the assembly, held a short speech:

Raised is then once more within the boundaries of Norway the ancient throne which was occupied by Haakon the Good and Sverre, from which they ruled old Norway with wisdom and strength. That the wisdom and power exercised by them, the great kings of our ancient past, also will inspire the Prince which we, the free men of Norway, in accordance with the wish of all the people, in gratitude and appreciation today unanimously have chosen, is a wish that every true son of Norway surely shares with me. God save old Norway!

The last sentence was then repeated by all those present.

On May 20, the assembly adjourned, joining hands and proclaiming that they would remain "United and loyal until the mountains of Dovre crumble!"

Seeking domestic and international legitimacy

On May 22, the newly elected king made a triumphant entrance into Christiania, exactly one year after he first arrived as viceroy to Norway. The cannons at Akershus Fortress sounded off the royal salute, and a celebratory service was held in the cathedral. There was continuing concern about the international climate, and on May 24 the government decided to send two of the delegates from the constitutional assembly to join Carsten Anker in the UK to plead Norway's case.

On May 25 the first council of state convened, establishing the nation's supreme court.

On May 31, general major Johannes Klingenberg Sejersted proposed to take a stand against invading Swedish forces at the river Glomma, but some maintanined that the Swedes should be stopped at the border.

On June 5, the British emissary John Philip Morier arrived in Christiania on what appeared to be an unofficial visit. He accepted the hospitality of one of Christian Frederick's ministers and agreed to meet with the king himself informally, stressing that nothing he did should be construed as a recognition of Norwegian independence. It was rumoured that Morier wanted Bernadotte deposed and exiled to the Danish island of Bornholm.

Christian Frederick asked the United Kingdom to mediate between Norway and Sweden, but Morier never deviated from the British rejection of an independent Norway. He offered to bring the Norwegian emissaries Niels Aall and Wilhelm Christie to the UK on his ship, but did not follow through on his promise. He demanded that Norway subject itself to Swedish supremacy, and also that his government's position be printed in all Norwegian newspapers. On June 10, the Norwegian army was mobilized and arms and ammunitions distributed.

On June 13, Christian Frederick also ordered a census in preparation for parliamentary elections.

On June 16, Carsten Anker sent a letter to Christian Frederick in which he made references to discussions he had recently had with a high-ranking Prussian diplomat. He learned that Prussia and Austria were waning in their support of Sweden's claims to Norway, that Alexander I of Russia (a distant cousin of Christian Frederick's) favoured a Swedish-Norwegian union but not with Bernadotte as the king, and that the United Kingdom was looking for a solution to the problem that would keep Norway out of Russia's influence.

Prelude to war

On June 26, emissaries from Russia, Prussia, Austria, and the United Kingdom arrived in Vänersborg in Sweden to convince Christian Frederick to comply with the provisions of the treaty of Kiel. There they conferred with von Essen, who told them that 65,000 Swedish troops were ready to invade Norway. On June 30 the emissaries arrived in Christiania, where they rudely turned down Christian Frederick's hospitality. Meeting with the Norwegian council of state the following day, the Russian emissary Orlow put the choice to those present: Norway could subject itself to the Swedish crown or face war with the rest of Europe. When Christian Frederik argued that the Norwegian people had a right to determine their own destiny, the Austrian emissary August Ernst Steigentesch made the famous comment:

- The people? What do they have to say against the will of its rulers? That would be to put the world on its head.

In the course of the negotiations, Christian Frederick offered to relinquish the throne and return to Denmark, provided the Norwegians had a say in their future through an extraordinary session in the Storting. But he refused to surrender the Norwegian border forts to Swedish troops. On 15 July the four-power delegation rejected Christian Frederick's proposal that Norway's constitution form the basis for negotiations about a union with Sweden, but promised to put the proposal to the Swedish king for consideration. The negotiations were a partial success in that the delegation left convinced that Christian Frederick was sincere and had the backing of a popular movement.

On July 20, Bernadotte sent a letter to his "cousin" Christian Frederick accusing him of intrigues and foolhardy adventurism. To add to the problems, the three Norwegians who had made their way to London were arrested, charged with carrying false passports and papers. They were deported immediately.

On July 22, Bernadotte met with the delegation that had been in Norway. They encouraged him to consider Christian Frederick's proposed terms for a union with Sweden, but the crown prince was outraged. He reiterated his ultimatum that Christian Frederick either relinquish all rights to the throne and abandon the border posts, or face war. On July 27, a Swedish naval fleet took over Hvaler, effectively putting Sweden at war with Norway. The day after, Christian Frederick rejected the Swedish ultimatum, saying that such a surrender would constitute treason against the Norwegian people. On July 29, Swedish forces moved to invade Norway.

A short war with two winners

Swedish forces met with little resistance as they advanced northward into Norway, bypassing the fortress of Fredriksten. The first hostilities were short and ended with decisive victories for Sweden. By August 4, the fortified city of Fredrikstad surrendered. Christian Frederick ordered a retreat to the river Glomma. The Swedish Army, trying to intercept the retreat, was stopped at the battle of Langnes, an important tactical victory by the Norwegians. The Swedish assaults from the east were effectively resisted near Kongsvinger.

On August 3 Christian Frederick announced his political will in a cabinet meeting in Moss. On August 7 a delegation from Bernadotte arrived at the Norwegian military headquarters in Spydeberg with a cease-fire offer that would join Norway in a union with Sweden and respect the Norwegian constitution. The day after, Christian Frederick expressed himself in favor of the terms, allowing Swedish troops to remain in positions east of Glomma. Hostilities broke out at Glomma, resulting in casualties, but the Norwegian forces were ordered to retreat. Peace negotiations with Swedish envoys began in the town of Moss on August 10. On August 14, the negotiations concluded. The Convention of Moss resulted in a general cease-fire based on terms that effectively were terms of peace.

Christian Frederick succeeded in excluding from the text any indication that Norway had recognized the Treaty of Kiel, and Sweden accepted that it was not to be considered a premise of the future union between the two states. Understanding the advantage of avoiding a costly war, and of letting Norway enter into a union voluntarily instead of being annexed as a conquered territory, something that, historically, the Swedes had never managed to do, Bernadotte offered favourable peace terms. He promised to recognize the Norwegian Constitution, with only those amendments that were necessary to open up for a union of the two countries. Christian Frederick agreed to call an extraordinary session of the Storting in September or October. He would then have to transfer his powers to the elected representatives of the people, who would negotiate the terms of the union with Sweden, and finally relinquish all claims to the Norwegian throne and leave the country.

An uneasy, but durable cease-fire

The news hit the Norwegian public hard, and reactions included anger at the "cowardice" and "treason" of the military commanders, despair over the prospects of Norwegian independence, and confusion about the country's options. Christian Frederick confirmed his willingness to abdicate the throne for "reasons of health," leaving his authority with the state council as agreed in a secret protocol at Moss. In a letter dated August 28, Christian Frederick ordered the council to accept orders from the "highest authority," clearly referring to the Swedish king. Two days later, the Swedish king proclaimed himself the ruler of both Sweden and Norway.

On September 3, the British announced that the naval blockade of Norway was lifted. Postal service between Norway and Sweden was resumed. By September 8, prominent Norwegians were taking note of the generous terms offered by Bernadotte. The Swedish general in the occupied border regions of Norway, Magnus Fredrik Ferdinand Björnstjerna, threatened to resume hostilities if the Norwegians would not abide by the armistice agreement and willingly accept the union with Sweden. Christian Frederik was reputed to have fallen into a deep depression and was variously blamed for the battleground defeats.

In late September, a dispute arose between Swedish authorities and the Norwegian council of state over the distribution of grain among the poor in Christiania. The grain was intended as a gift from the Swedish king to the Norwegians, but it became a matter of principle for the Norwegian council to avoid the appearance that Norway had a new king until the transition was formalized. Björnstjerna sent several missives threatening to resume hostilities.

On 26 September, the Norwegian general in the "northern" region of Norway, Count Carl Jacob Waldemar von Schmettow, vowed in Norwegian newspapers to forcibly resist any further Swedish troop movements into Norway.

Easing into a new arrangement

In early October, Norwegians again refused to accept a shipment of corn from Bernadotte, and Norwegian merchants instead took up loans to purchase food and other necessities from Denmark. However, by early October, there was emerging support for a union with Sweden. On October 7, an extraordinary session of the Norwegian parliament convened. Delegates from areas occupied by Sweden in Østfold were admitted only after submitting assurances that they had no loyalty to the Swedish authorities. On October 10, Christian Frederick formally abdicated according to the conditions agreed on at Moss and embarked for Denmark. Executive powers were provisionally assigned to the Storting, until the necessary amendments to the Constitution were enacted.

On October 20, with one day to spare before the cease-fire expired, the Norwegian parliament voted 72 to 5 to join Sweden in a personal union, but a motion to acknowledge Charles XIII as king of Norway failed to pass. The issue was tabled pending the necessary amendments to the Norwegian constitution. In the following days, the parliament passed several resolutions to assert as much sovereignty as possible within the union. On November 1, they voted 52 to 25 that Norway would not appoint its own consuls, a decision that would have serious consequences in 1905. On November 4, the Storting adopted the constitutional amendments that were required to allow for the union, and unanimously elected Charles XIII as king of Norway, rather than acknowledging him as such.

References

- ^ Demographics of Norway, Jan Lahmeyer. Retrieved on 8 March 2014.

- ^ Glenthøj, Rasmus (2012):Skilsmissen. Dansk og norsk identitet før og efter 1814. Syddansk Universitetsforlag, p. 80-81

- ^ Linvald, Axel (1962): Christian Frederik og Norge 1814. Oslo, Universitetsforlaget, pp. 10-1

- ^ Koht, Halvdan (1910):Unionssprengninga i 1814 i verdshistorisk samanheng. Kristiania, Det norsk Samlaget, pp. 3-15

- ^ Steen, Sverre (1951): 1814. Oslo, J.W. Cappelen. Pp. 49-50

- ^ Steen, Sverre (1951): 1814. Oslo, J.W. Cappelen. Pp. 60-61

- ^ Linvald, Axel (1962): Christian Frederik og Norge 1814. PP. 19-20

- ^ Pavels, Claus: Dagbøker 1812-1822. 26–31 January. www.dokpro.uio.no/litteratur/pavels/frames.htm

- ^ Norway Paper Money Prinsesedler Ca. 1815 Issues http://numismondo.net/pm/nor/index03A.htm

Literature

- Glenthøj, Rasmus and Morten Nordhagen Ottosen (2014): 1814 Krig, nederlag, frihet. Oslo, Spartacus forlag AS. ISBN 978-82-430-0813-7

- Koht, Halvdan (1910): Unionsprengningen i 1814 i verdenshistorisk sammenheng. Kristiania, Det norske Samlaget

- Koht, Halvdan (1914): 1814. Norsk dagbok hundre aar efterpaa. Kristiania

- Linvald, Axel (1962): Christian Frederik og Norge 1814. Oslo, Universitetsforlaget.

- Nielsen, Yngvar (1905): Norge i 1814. Christiania, J.M. Stenersen & Co.

- Pavels, Claus (1864): Claus Pavels biografi og dagbøger 1812-1822/Udgivne i uddrag af Claus Pavels Riis. Bergen, Floor

- Steen, Sverre (1951): 1814. Oslo, J.W. Cappelen