National Building Museum

Pension Building | |

National Building Museum in 2023 | |

Interactive fullscreen map | |

| Location | 401 F St. NW, Washington, D.C., U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°53′51.0″N 77°1′5.2″W / 38.897500°N 77.018111°W |

| Built | 1887 |

| Architect | Montgomery C. Meigs |

| Architectural style | Renaissance Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 69000312[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | March 24, 1969 |

| Designated NHL | February 4, 1985 |

The National Building Museum is a museum of architecture, design, engineering, construction, and urban planning in Northwest Washington, D.C., U.S. It was created by an act of Congress in 1980, and is a private non-profit institution. Located at 401 F Street NW, it is adjacent to the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial and the Judiciary Square Metro station. The museum hosts various temporary exhibits in galleries around the spacious Great Hall.

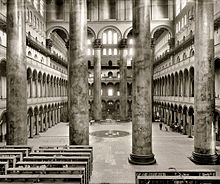

The building, completed in 1887, served as the Pension Building, housing the United States Pension Bureau, and hosted several presidential inaugural balls. It is centered around a high-columned interior central courtyard hall often used for various events. It is an important early large-scale example of Renaissance Revival architecture, and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1985.

Pension Building

[edit]

The National Building Museum is housed in the former Pension Bureau building, a brick structure completed in 1887 and designed by Montgomery C. Meigs, the U.S. Army quartermaster general.[2] It is notable for several architectural features, including the spectacular interior columns and a frieze, sculpted by Caspar Buberl, stretching around the exterior of the building and depicting Civil War soldiers in scenes somewhat reminiscent of those on Trajan's Column as well as the Horsemen Frieze of the Parthenon. The vast interior, measuring 316 × 116 feet (96 × 35 m),[4] has been used to hold inauguration balls; a Presidential Seal is set into the floor near the south entrance.

After the Civil War, the United States Congress passed legislation that greatly extended the scope of pension coverage for veterans and their survivors and dependents, notably their widows and orphans. The number of staff needed to implement and administer the new benefits system ballooned to over 1,500, and quickly required a new building from which to run it all. Meigs was chosen to design and construct the new building. He departed from the established Greco-Roman models that had been the basis of government buildings in Washington, D.C., until then and which continued after the Pension Building's completion. Meigs based his design on Italian Renaissance precedents, notably Rome's Palazzo Farnese and the Palazzo della Cancelleria.[4]

Included in his design was a frieze sculpted by Caspar Buberl. Because a sculpture of that size was well out of Meigs's budget, he had Buberl create 28 different scenes, totaling 69 feet (21 m) in length, which were then mixed and slightly modified to create the continuous 1,200-foot (365-m) parade of over 1,300 figures. Because of the 28 sections' modification and mixture, it is only in careful examination that the frieze is seen to be the same figures repeated several times. The sculpture includes infantry, navy, artillery, cavalry, and medical components, as well as a good deal of the supply and quartermaster functions, for it was in that capacity that Meigs had served during the Civil War.

Meigs's correspondence with Buberl reveals that Meigs insisted that a black teamster, who "must be a negro, a plantation slave, freed by war", be included in the quartermaster panel. This figure was ultimately to assume a central position, over the building's west entrance.

Built before modern artificial ventilation, the building was designed to maximize air circulation: all offices not only had exterior windows, but also opened onto the court, which was designed to admit cool air at ground level and exhaust hot air at the roof. Made of brick and tile, the stairs were designed for the limitations of disabled and aging veterans, having a gradual ascent with low steps. In addition, each step slanted slightly from back to front to allow easy drainage: a flight could be washed easily by pouring water from the top.

When Philip Sheridan was asked to comment on the building, his biting reply echoed the negative sentiment of much of the Washington establishment of the day: "Too bad the damn thing is fireproof." A similar quote is also attributed to William Tecumseh Sherman, perhaps casting doubt on the truth of the Sheridan tale. Longtime Washington journalist Benjamin Perley Poore called the building a "hideous architectural monstrosity."[5]

The completed building, sometimes called "Meigs Old Red Barn", required more than 15 million bricks,[6] which, according to the wit of the day, were each counted by the parsimonious Meigs.

Becoming a museum

[edit]

The building was used for federal government offices until the 1960s when it had fallen into a state of disrepair and was considered for demolition. After pressure from conservationists, the government commissioned a report by architect Chloethiel Woodard Smith of possible other uses for the building. Her 1967 report suggested a museum dedicated to the building arts. The building was then listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1969. At that time, the building was still in use as the local draft bureau office. In 1980, Congress created the National Building Museum as a private, non-profit institution. The building itself was formally renamed the National Building Museum in 1997.[4]

Every year, the annual Christmas in Washington program was filmed at the museum, with the president and first lady, until the show's cancellation in 2015.

Museum shop

[edit]The National Building Museum's gift shop was honored in 2007 as the "Best Museum Store" in the country by Niche magazine, "Best All-Around Museum Shop" in the region by The Washington Post,[7] a "Top Shop" by the Washingtonian,[8] and named best museum shop in D.C. by National Geographic Traveler's blog, Intelligent Travel, in July 2009.[9] In 2010, The Huffington Post included the National Building Museum in its story "Museums with Amazing Gift Shops."[10] The museum shop sells books about the built environment and an array of housewares, educational toys, watches, and items for an office, all with an emphasis on design.

American politics

[edit]On June 7, 2008, Hillary Clinton suspended her campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination with a farewell rally inside the museum.[11] On that occasion, Clinton memorably declared that "if we can blast fifty women into space, we will someday launch a woman into the White House."[12]

Awards

[edit]The National Building Museum presents three annual awards: the Honor Award for individuals and organizations who have made important contributions to the U.S.'s building heritage; the Vincent Scully Prize, which honors exemplary practice, scholarship, or criticism in architecture, historic preservation, and urban design; and the Henry C. Turner Prize for Innovation in Construction Technology, which recognizes outstanding leadership and innovation in the field of construction methods and processes.[citation needed]

Outreach programs

[edit]Investigating Where We Live

[edit]Investigating Where We Live is a summer program for teens from the DC metropolitan area. Students spend four weeks in teams equipped with cameras, and sketchbooks to discover the local communities. Students are given an introduction to photography and then investigate neighborhoods in Washington, D.C. Documenting history, landmarks, and residential areas, students assemble the community's identity. The original photographs and writings are incorporated into an exhibition at the Museum. Since 1996, more than 500 students have participated in learning about different communities within the District of Columbia.[13] Upon completion of the program, participants:

- Receive a digital camera

- Develop relationships with professional photographers, designers, museum staff, and fellow participants

- Keep photographs for use in future projects, portfolios, or high school and college applications

- Fulfill community service requirements for school[14]

Previous exhibits include "Investigating Where We Live: Recapturing Shaw's Legacy" which taught high school students about DC's Shaw neighborhood.[15][16]

Images

[edit]-

National Building Museum with the United States Capitol in the background

-

National Building Museum

-

National Building Museum from the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial on F Street NW

-

Corner figures, exterior frieze

-

South entrance

-

US Navy sailors

-

Artillery

-

Cavalry

-

Infantry

-

Black teamster, exterior frieze

-

Great Hall during 2010 Honor Award ceremony

-

2005 Vincent Scully Prize ceremony

-

Gallery in the 2008-2009 exhibition Green Community

-

Family activity at the 2008 Festival of the Building Arts

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ^ a b "National Building Museum Facts". National Building Museum. Archived from the original on June 1, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ NBM About, By the Numbers

- ^ a b c "Our Historic Building". National Building Museum. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Poore, Ben. Perley, Perley's Reminiscences of Sixty Years in the National Metropolis, Vol.2, p.471 (1886).

- ^ National Building Museum Web Site Archived July 7, 2010, at the Wayback Machine retrieved June 27, 2010

- ^ "And the Winners Are...". Washington Post. December 8, 2000.

- ^ Mary Clare Glover (July 1, 2007). "Top Museum Shops". Washingtoanian.

- ^ Sarah Aldrich (July 29, 2009). "10 Best Museum Shops in DC". Intelligent Travel, National Geographic. Archived from the original on April 14, 2010.

- ^ "Museums With Amazing Gift Shops, Ripe For Holiday Shopping (PHOTOS)". Huffington Post travel. December 3, 2010.

- ^ Nagourney, Adam; Mark Leibovich (June 8, 2008). "Ending Her Bid, Clinton Backs Obama". The New York Times. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ^ The Washington Post. "44 – Clinton's Last Hurrah." Anne E. Kornblut. 7 June 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2012.

- ^ "National Building Museum: Investigating Where We Live – Recapturing Shaw's Legacy | DowntownDC". Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- ^ "Teen programs and events at the National Building Museum". Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- ^ "Investigating Where We Live: Recapturing Shaw's Legacy at national Building Museum". Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- ^ Morello, Carol (July 6, 2013). "National Building Museum helps teens explore Shaw, a neighborhood in transition". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013.

Further reading

[edit]- Lyons, Linda Brody, Building a Landmark: A Guide to the Historic Home of the National Building Museum, National Building Museum, Washington, D.C., 1999

- McDaniel, Joyce L., The Collected Works of Caspar Buberl: An Analysis of a Nineteenth Century American Sculptor, MA thesis, Wellesley College, Wellesley, Massachusetts, 1976

- Weeks, Christopher, AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington, D.C., 3rd ed., Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994, pp. 73–74.

- Schiavo, Laura Burd. National Building Museum: Art Spaces. New York: Scala Publishers, 2007.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. DC-76, "Pension Building, 440 G Street Northwest, Washington, District of Columbia, DC", 57 photos, 4 color transparencies, 1 measured drawing, 9 data pages, 6 photo caption pages

- National Park Service – National Historic Landmarks Program – Pension Building listing

- General Services Administration page on the Pension Building (National Building Museum)

- National Building Museum Investigating Where We Live

- Washington City Paper

- Washington Post

- Downtown DC

- National Building Museum within Google Arts & Culture

Media related to National Building Museum at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to National Building Museum at Wikimedia Commons

- 1980 establishments in Washington, D.C.

- Architecture museums in the United States

- Government buildings completed in 1887

- Historic American Buildings Survey in Washington, D.C.

- Industry museums in Washington, D.C.

- Buildings and structures in Judiciary Square

- Members of the Cultural Alliance of Greater Washington

- National Historic Landmarks in Washington, D.C.

- National museums of the United States

- Organizations based in Washington, D.C.

- Organizations established in 1980

- Private congressionally designated national museums of the United States

- Renaissance Revival architecture in Washington, D.C.

- Sculptures of African Americans