Polish government-in-exile

Government of the Republic of Poland in exile Rząd Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na uchodźstwie | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1939–1990 | |||||||||

| Anthem: Mazurek Dąbrowskiego "Poland Is Not Yet Lost" | |||||||||

| Status | Government in exile | ||||||||

| Capital-in-exile | Paris (1939–1940) Angers (1940) London (1940–1990) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Polish | ||||||||

| Government | Republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

• 1939–1947 | Władysław Raczkiewicz (first) | ||||||||

• 1989–1990 | Ryszard Kaczorowski (last) | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

• 1939–1940 | Władysław Sikorski (first) | ||||||||

• 1986–1990 | Edward Szczepanik (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | World War II / Cold War | ||||||||

| 23 April 1935 | |||||||||

| 17 September 1939 | |||||||||

| 22 December 1990 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| Polish Underground State |

|---|

|

The Polish government-in-exile, formally known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile (Template:Lang-pl), was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Poland of September 1939, and the subsequent occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, which brought to an end the Second Polish Republic.

Despite the occupation of Poland by hostile powers, the government-in-exile exerted considerable influence in Poland during World War II through the structures of the Polish Underground State and its military arm, the Armia Krajowa (Home Army) resistance. Abroad, under the authority of the government-in-exile, Polish military units that had escaped the occupation fought under their own commanders as part of Allied forces in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East.

After the war, as the Polish territory came under the control of the People's Republic of Poland, a Soviet satellite state, the government-in-exile remained in existence, though largely unrecognized and without effective power. Only after the end of Communist rule in Poland did the government-in-exile formally pass on its responsibilities to the new government of the Third Polish Republic in December 1990.

The government-in-exile was based in France during 1939 and 1940, first in Paris and then in Angers. From 1940, following the Fall of France, the government moved to London, and remained in the United Kingdom until its dissolution in 1990.

History

Establishment

On 17 September 1939, the President of the Polish Republic, Ignacy Mościcki, who was then in the small town of Kuty (now Ukraine)[1][2][3] near the southern Polish border, issued a proclamation about his plan to transfer power and appointing Władysław Raczkiewicz, the Marshal of the Senate, as his successor.[1][2] This was done in accordance with Article 24[4][5] of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland, adopted in April 1935,[4][6] which provided as follows:

In event of war, the term of the President's office shall be prolonged until three months after the conclusion of peace; the President of the Republic shall then, by a special act promulgated in the Official Gazette, appoint his successor, in case the office falls vacant before the conclusion of peace. Should the President's successor assume office, the term of his office shall expire at the end of three months after the conclusion of peace.[5]

It was not until 29th[6] or 30th[4][5][7] September 1939 that Mościcki resigned. Raczkiewicz, who was already in Paris, immediately took his constitutional oath at the Polish Embassy and became President of the Republic of Poland. He then appointed General Władysław Sikorski to be Prime Minister[7][8] and, following Edward Rydz-Śmigły's stepping down,[9] made Sikorski Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Armed Forces.[8][9]

Most of the Polish Navy escaped to Britain,[10] and tens of thousands of Polish soldiers and airmen escaped through Hungary and Romania or across the Baltic Sea to continue the fight in France.[11] Many Poles subsequently took part in Allied operations in Norway (Narvik[12]), France, the Battle of Britain, the Battle of the Atlantic, North Africa (notably Tobruk[13]), Italy (notably at Cassino and Ancona), Arnhem, Wilhelmshaven and elsewhere beside other Allied forces. Even after the fall of Poland, Poland remained the third strongest Allied belligerent, after France and Britain. After Germany terminated its 1939 alliance with the Soviets in June 1941, with Hitler's attack on Soviet forces occupying eastern Poland, Polish forces grew yet again as all of Poland's citizens held captive in Soviet forced labour were released under the Sikorski–Mayski Agreement to form military units to fight Nazi Germany under Allied command.

Wartime history

The Polish government in exile, based first in Paris, then in Angers, France,[14] where Władysław Raczkiewicz lived at the Château de Pignerolle near Angers from 2 December 1939 until June 1940.[15] Escaping from France the government relocated to London, it was recognized by all the Allied governments. Politically, it was a coalition of the Polish Peasant Party, the Polish Socialist Party, the Labour Party and the National Party,[6] although these parties maintained only a vestigial existence in the circumstances of war.

When Germany launched a war against the USSR in 1941, the Polish government in exile established diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union against Hitlerism, but also in order to help Poles persecuted by the NKVD.[16][17] On 12 August 1941 the Kremlin signed a one-time amnesty,[18] extending to thousands of Polish soldiers who had been taken prisoner in 1939 by the Red Army in eastern Poland, including many Polish civilian prisoners and deportees entrapped in Siberia.[19] The amnesty allowed the Poles to create eight military divisions known as the Anders Army.[19] They were evacuated to Iran and the Middle East, where they were desperately needed by the British, hard pressed by Rommel's Afrika Korps. These Polish units formed the basis for the Polish II Corps, led by General Władysław Anders, which together with other, earlier-created Polish units fought alongside the Allies.[19]

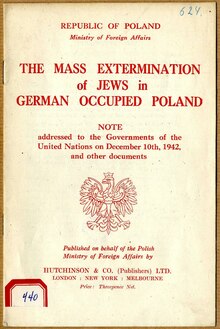

During the war, especially from 1942 on, the Polish government in exile provided the Allies with some of the earliest and most accurate accounts of the ongoing Holocaust of European Jews[20][21] and, through its representatives, like the Foreign Minister Count Edward Raczyński and the courier of the Polish Underground movement, Jan Karski, called for action, without success, to stop it.

In April 1943, the Germans announced that they had discovered at Katyn Wood, near Smolensk, Russia, mass graves of 10,000 Polish officers[22][23] (the German investigation later found 4,443 bodies[24]) who had been taken prisoner in 1939 and murdered by the Soviets. The Soviet government said that the Germans had fabricated the discovery. The other Allied governments, for diplomatic reasons, formally accepted this; the Polish government in exile refused to do so.

Stalin then severed relations with the Polish government in exile. Since it was clear that it would be the Soviet Union, not the western Allies, who would liberate Poland from the Germans, this breach had fateful consequences for Poland. In an unfortunate coincidence, Sikorski, widely regarded as the most capable of the Polish exile leaders, was killed in an air crash at Gibraltar in July 1943.[25] He was succeeded as head of the Polish government in exile by Stanisław Mikołajczyk.

During 1943 and 1944, the Allied leaders, particularly Winston Churchill, tried to bring about a resumption of talks between Stalin and the Polish government in exile. But these efforts broke down over several matters. One was the Katyń massacre (and others at Kalinin and Kharkiv). Another was Poland's postwar borders. Stalin insisted that the territories annexed by the Soviets in 1939, which had millions of Poles in addition to Ukrainian and Belarusian populations,[26] should remain in Soviet hands, and that Poland should be compensated with lands to be annexed from Germany. Mikołajczyk, however, refused to compromise on the question of Poland's sovereignty over her prewar eastern territories. A third matter was Mikołajczyk's insistence that Stalin not set up a Communist government in postwar Poland.

Postwar history

Mikołajczyk and his colleagues in the Polish government-in-exile insisted on making a stand in the defense of Poland's pre-1939 eastern border (retaining its Kresy region) as a basis for the future Polish-Soviet border.[27] However, this was a position that could not be defended in practice – Stalin was in occupation of the territory in question. The government-in-exile's refusal to accept the proposed new Polish borders infuriated the Allies, particularly Churchill, making them less inclined to oppose Stalin on issues of how Poland's postwar government would be structured. In the end, the exiles lost on both issues: Stalin annexed the eastern territories, and was able to impose the communist-dominated Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland as the legitimate authority of Poland. However, Poland preserved its status as an independent state, despite the arguments of some influential Communists, such as Wanda Wasilewska, in favor of Poland becoming a republic of the Soviet Union.

In November 1944, despite his mistrust of the Soviets, Mikołajczyk resigned[28] to return to Poland and take office in the Provisional Government of National Unity, a new government established under the auspices of the Soviet occupation authorities comprising his faction and much of the old Provisional Government. Many Polish exiles opposed this action, believing that this government was a façade for the establishment of Communist rule in Poland. This view was later proven correct in 1947, when the Communist-dominated Democratic Bloc won a blatantly rigged election. The Communist-dominated bloc was credited with over 80 percent of the vote, a result that was only obtained through large-scale fraud. The opposition claimed it would have won in a landslide (as much as 80 percent, by some estimates) had the election been honest. Mikołajczyk, who would have likely become prime minister had the election been truly free, feared for his life and fled Poland in April 1947, this time never to return.

Meanwhile, the Polish government in exile had maintained its existence, but France on 29 June 1945,[6] then the United States and United Kingdom on 5 July 1945[6][29] withdrew their recognition. The Polish Armed Forces in exile were disbanded in 1945, and most of their members, unable to safely return to Communist Poland, settled in other countries. The London Poles had to vacate the Polish embassy on Portland Place and were left only with the president's private residence at 43 Eaton Place. The government in exile became largely symbolic of continued resistance to foreign occupation of Poland, while retaining some important archives from prewar Poland. The Republic of Ireland, Francoist Spain and the Vatican City (until 1979) were the last countries to recognize the government in exile, though the Vatican – through Secretary of State Domenico Tardini – had withdrawn diplomatic privileges from the envoy of the Polish pre-war government in 1959.[30]

In 1954, political differences led to a split in the ranks of the government in exile. One group, claiming to represent 80% of 500,000 anti-Communist Poles exiled since the war, was opposed to President August Zaleski's continuation in office when his seven-year term expired. It formed a Council of National Unity in July 1954, and set up a Council of Three to exercise the functions of head of state, comprising Tomasz Arciszewski, General Władysław Anders, and Edward Raczyński. Only after Zaleski's death in 1972 did the two factions reunite.

Some supporters of the government in exile eventually returned to Poland, such as Prime Minister Hugon Hanke in 1955 and his predecessor Stanisław Mackiewicz in 1956. The Soviet-installed government in Warsaw campaigned for the return of the exiles, promising decent and dignified employment in communist Polish administration and forgiveness of past transgressions.

Despite these setbacks, the government in exile continued in existence. When Soviet influence over Poland came to an end in 1989, there was still a president and a cabinet of eight meeting every two weeks in London, commanding the loyalty of about 150,000 Polish veterans and their descendants living in Britain, including 35,000 in London alone.

In December 1990, when Lech Wałęsa became the first post-Communist president of Poland since the war, he received the symbols of the Polish Republic (the presidential banner, the presidential and state seals, the presidential sashes, and the original text of the 1935 Constitution) from the last president of the government in exile, Ryszard Kaczorowski.[31] In 1992, military medals and other decorations awarded by the government in exile were officially recognized in Poland.

Government and politics

Presidents

| # | President | Picture | Took office | Left office | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Władysław Raczkiewicz |  |

30 September 1939 | 6 June 1947 | Died in office |

| 2 | August Zaleski |  |

9 June 1947 | 8 April 1972 | Died in office, longest-serving President |

| 3 | Stanisław Ostrowski |  |

9 April 1972 | 24 March 1979 | |

| 4 | Edward Raczyński |  |

8 April 1979 | 8 April 1986 | |

| 5 | Kazimierz Sabbat |  |

8 April 1986 | 19 July 1989 | Died in office |

| 6 | Ryszard Kaczorowski |  |

19 July 1989 | 22 December 1990 | Transferred authority to Lech Wałęsa on his inauguration. Died on 10 April 2010 in 2010 Polish Air Force Tu-154 crash in Smolensk. |

Prime ministers

| L.p. | Portrait | Name | Entered office | Left office |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. |

|

Władysław Sikorski (2nd term) |

30 September 1939 20 July 1940 |

18 July 1940 4 July 1943 |

| 2. |

|

Stanisław Mikołajczyk | 14 July 1943 | 24 November 1944 |

| 3. |

|

Tomasz Arciszewski | 29 November 1944 | 2 July 1947 |

| 4. |

|

Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski | 2 July 1947 | 10 February 1949 |

| 5. |

|

Tadeusz Tomaszewski | 7 April 1949 | 25 September 1950 |

| 6. |

|

Roman Odzierzyński | 25 December 1950 | 8 December 1953 |

| 7. |

|

Jerzy Hryniewski | 18 January 1954 | 13 May 1954 |

| 8. |

|

Stanisław Cat-Mackiewicz | 8 June 1954 | 21 June 1955 |

| 9. |

|

Hugon Hanke | 8 August 1955 | 10 September 1955 |

| 10. |

|

Antoni Pająk | 10 September 1955 | 14 June 1965 |

| 11. |

|

Aleksander Zawisza | 25 June 1965 | 9 June 1970 |

| 12. |

|

Zygmunt Muchniewski | 20 July 1970 | 13 July 1972 |

| 13. |

|

Alfred Urbański | 18 July 1972 | 15 July 1976 |

| 14. |

|

Kazimierz Sabbat | 5 August 1976 | 8 April 1986 |

| 15. |

|

Edward Szczepanik | 8 April 1986 | 22 December 1990 |

Armed forces

- Association of Armed Struggle (Związek Walki Zbrojnej, ZWZ)

- Home Army (Armia Krajowa)

- Grey Ranks (Szare Szeregi)

- Polish resistance movement in World War II

- Polish Armed Forces in the West

- Polish Armed Forces in the East

See also

- Jan Karski, resistance fighter.

- Tadeusz Chciuk-Celt, special envoy of the government.

- Ignacy Schwarzbart

- Szmul Zygielbojm

- Henryk Leon Strasburger, Finance Minister and Minister in the Middle East for the Sikorski government; Ambassador to London for Mikolajczyk.

- Juliusz Nowina-Sokolnicki, alternative President of the Republic of Poland (1972–1990).

- Polish Committee of National Liberation (Polski Komitet Wyzwolenia Narodowego, PKWN), 1944–1945.

- Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland (Rząd Tymczasowy Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, RTRP), 1945.

- Provisional Government of National Unity (Tymczasowy Rząd Jedności Narodowej, TRJN), 1945–1947.

- People's Republic of Poland (Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL), 1944–1952 (unofficial), 1952–1989 (official).

- Western betrayal

References

- ^ a b Count Edward Raczynski In Allied London Weidenfeld and Nicolson 1962 Page 39

- ^ a b Editor Waclaw Jedrzejewicz Poland in the British Parliament 1939-1945 Volume I Jozef Pilsudski 1946 Page 317

- ^ John Coutouvidis & Jamie Reynolds Poland 1939-1947 ISBN 0-7185-1211-1 Page 20

- ^ a b c Jozef Garlinski Poland in the Second World War, ISBN 0-333-39258-2 Page 48

- ^ a b c Editor Waclaw Jedrzejewicz Poland in the British Parliament 1939-1945 Volume I Jozef Pilsudski 1946 Page 318

- ^ a b c d e Editor Peter D. Stachura Chapter 4 by Wojciech Rojek The Poles in Britain 1940-2000 ISBN 0-7146-8444-9 Page 33

- ^ a b Johbjkuinhojvn Coutouvidis & Jamie Reynolds Poland 1939-1947 ISBN 0-7185-1211-1 Page 26

- ^ a b Editor Kieth Sword Sikorski: Soldier and Statesman ISBN 0-901149-33-0

- ^ a b Jozef Garlinski Poland in the Second World War, ISBN 0-333-39258-2 Page 49

- ^ Jozef Garlinski Poland in the Second World War, ISBN 0-333-39258-2 Pages 17-18

- ^ Jozef Garlinski Poland in the Second World War, ISBN 0-333-39258-2 Page 55-56

- ^ The Poles on the Battlefronts of the Second World War Bellona 2005 Page 29

- ^ The Poles on the Battlefronts of the Second World War Bellona 2005 Page 37

- ^ Jozef Garlinski Poland in the Second World War, ISBN 0-333-39258-2 Page 81

- ^ "Pignerolle dans la Seconde Guerre mondiale".

- ^ Stanislaw Mikolajczyk The Pattern of Soviet Domination Sampson Low, Marston & Co 1948 Page 17

- ^ Wojciech Roszkowski The Shadow of Yalta ISBN 83-60142-00-9 Page 27

- ^ Tadeusz Piotrowski (2004). "Amnesty". The Polish Deportees of World War II: Recollections of Removal to the Soviet Union and Dispersal Throughout the World. McFarland. pp. 93–94, 102. ISBN 0786455365 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Stanisław Mikołajczyk (1948). The Pattern of Soviet Domination. Sampson Low, Marston & Co. pp. 19, 26. OCLC 247048466.

- ^ Note of the Foreign Minister Edward Raczynski "The mass extermination of Jews in German occupied Poland, Note addressed to the Governments of the United Nations on December 10th 1942", also published (30 December 1942) by the Polish Foreign Ministry as a public document with the aim to reach the public opinions of the Free World. See: http://www.projectinposterum.org/docs/mass_extermination.htm

- ^ Martin Gilbert, Auschwitz and the Allies, 1981 (Pimlico edition, p.101) "On december 10, the Polish Ambassador in London, Edward Raczynski sent Eden an extremely detailed twenty-one point summary of all the most recent information regarding the killing of Jews in Poland; confirmation, he wrote, "that the German authorities aim with systematic deliberation at the total extermination of the Jewish population of Poland" as well as of the "many thousands of Jews" whom the Germans had deported to Poland from western and Central Europe, and from the German Reich itself."

- ^ J.K.Zawodny Death in the Forest ISBN 0-87052-563-8 Page 15

- ^ Louis Fitzgibbon Katyn Massacre ISBN 0-552-10455-8 Page 126

- ^ J.K.Zawodny Death in the Forest ISBN 0-87052-563-8 Page 24

- ^ John Coutouvidis & Jamie Reynolds Poland 1939-1947 ISBN 0-7185-1211-1 Page 88

- ^ Elżbieta Trela-Mazur (1997). Włodzimierz Bonusiak; Stanisław Jan Ciesielski; Zygmunt Mańkowski; Mikołaj Iwanow (eds.). Sowietyzacja oświaty w Małopolsce Wschodniej pod radziecką okupacją 1939–1941. Kielce: Wyższa Szkoła Pedagogiczna im. Jana Kochanowskiego. pp. 294-. ISBN 8371331002 – via Google Books.

Of the 13.5 million civilians living in Polish areas annexed by the Soviet Union according to the last official Polish census, the population was over 38% Poles (5.1 million), 37% Polish Ukrainians (4.7 million), 14.5% Belarusians, 8.4% Jews, 0.9% Russians and 0.6% Germans.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) Also in: Wrocławskie Studia Wschodnie, Wrocław, 1997. - ^ John Coutouvidis & Jamie Reynolds Poland 1939-1947 ISBN 0-7185-1211-1 Pages 103-104

- ^ John Coutouvidis & Jamie Reynolds Poland 1939-1947 ISBN 0-7185-1211-1 Page 107

- ^ Peter D. Stachura, Editor The Poles in Britain 1940–2000, Frank Cass, 2004, ISBN 0-7146-8444-9, Paperback First Edition, p. 8.

- ^ Phantoms in Rome, TIME Magazine, 19 January 1959

- ^ Peter D. Stachura, Editor The Poles in Britain 1940–2000, Frank Cass, 2004, ISBN 0-7146-8444-9, Paperback First Edition, p. 45.

Further reading

- Cienciala, Anna M. "The Foreign Policy of the Polish Government-in-Exile, 1939–1945: Political and Military Realities versus Polish Psychological Reality" in: John S. Micgiel and Piotr S. Wandycz eds., Reflections on Polish Foreign Policy, New York: 2005. online

- Davies, Norman. God's Playground: A History of Poland, Vol. 2: 1795 to the Present (2005)

- Kochanski, Halik. The Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War (2012) excerpt and text search

External links

- Statement of the Polish government in exile following the death of General Sikorski (1943)

- Publications on the Polish government (in exile) 1939-1990

- Stamp Issues by the Polish government in exile

- Polish Chancellery website: Prime Ministers IInd Republic of Poland in exile

- Polish World War II website on the Polish government in exile

Multimedia

Republic in Exile tells the story of the Polish government-in-exile in the form of five short episodes available on the YouTube channel: Polish Embassy UK

- "Republic in Exile, Episode 1: War" on YouTube (12 December 2014), Polish Embassy UK

- "Republic in Exile, Episode 2: Poland outside Poland on YouTube (19 December 2014), Polish Embassy UK

- "Republic in Exile, Episode 3: Polish voice in the world on YouTube (26 December 2014), Polish Embassy UK

- "Republic in Exile, Episode 4: Solidarity on YouTube (9 January 2015), Polish Embassy UK

- "Republic in Exile, Episode 5: Free Poland on YouTube (16 January 2015), Polish Embassy UK

- 1990 disestablishments

- States and territories established in 1939

- Former governments in exile

- Governments in exile during World War II

- Polish Underground State

- History of Poland (1939–45)

- History of Poland (1945–89)

- History of Poland (1989–present)

- Government of Poland

- Political history of Poland

- Poland–United Kingdom relations

- 20th century in London

- History of the City of Westminster

- Polish exiles

- Polish expatriates in the United Kingdom

- British Empire in World War II

- United Kingdom in World War II