Polyphasic sleep

Polyphasic sleep, a term coined by early 20th-century psychologist J.S. Szymanski,[1] refers to the practice of sleeping multiple times in a 24-hour period—usually more than two, in contrast to biphasic sleep (twice per day) or monophasic sleep (once per day). It does not imply any particular sleep schedule. The circadian rhythm disorder known as irregular sleep-wake syndrome is an example of polyphasic sleep in humans. Polyphasic sleep is common in many animals, and is believed to be the ancestral sleep state.[2] The term polyphasic sleep, or often Uberman's sleep schedule, is also used by an online community which experiments with ultra-short napping to achieve more time awake each day.

Multiphasic sleep of normal total duration

An example of polyphasic sleep is found in patients with irregular sleep-wake syndrome, a circadian rhythm sleep disorder which usually is caused by head injury or dementia. Much more common examples are the sleep of human infants and of many animals. Elderly humans often have disturbed sleep, including polyphasic sleep.[3]

In their 2006 paper "The Nature of Spontaneous Sleep Across Adulthood," Campbell and Murphy studied sleep timing and quality in young, middle-aged and older adults. They found that, in freerunning conditions, the average duration of major nighttime sleep was significantly longer in young adults than in the other groups. The paper states further:

Whether such patterns are simply a response to the relatively static experimental conditions, or whether they more accurately reflect the natural organization of the human sleep/wake system, compared with that which is exhibited in daily life, is open to debate. However, the comparative literature strongly suggests that shorter, polyphasically-placed sleep is the rule, rather than the exception, across the entire animal kingdom (Campbell and Tobler, 1984; Tobler, 1989). There is little reason to believe that the human sleep/wake system would evolve in a fundamentally different manner. That people often do not exhibit such sleep organization in daily life merely suggests that humans have the capacity (often with the aid of stimulants such as caffeine or increased physical activity) to overcome the propensity for sleep when it is desirable, or is required, to do so.[4]

Napping in extreme situations

In crises and other extreme conditions, people may not be able to achieve the recommended eight hours of sleep per day. Systematic napping may be considered necessary in such situations.

Dr. Claudio Stampi, as a result of his interest in long-distance solo boat racing, has studied the systematic timing of short naps as a means of ensuring optimal performance in situations where extreme sleep deprivation is inevitable, but he does not advocate ultrashort napping as a lifestyle.[5] Scientific American Frontiers (PBS) has reported on Stampi's 49-day experiment where a young man napped for a total of three hours per day. It purportedly shows that all stages of sleep were included.[6] Stampi has written about his research in his book Why We Nap: Evolution, Chronobiology, and Functions of Polyphasic and Ultrashort Sleep (1992).[7] In 1989 he published results of a field study in the journal Work & Stress, concluding that "polyphasic sleep strategies improve prolonged sustained performance" under continuous work situations.[8]

The U.S. military

The U.S. military has studied fatigue countermeasures. An Air Force report states:

Each individual nap should be long enough to provide at least 45 continuous minutes of sleep, although longer naps (2 hours) are better. In general, the shorter each individual nap is, the more frequent the naps should be (the objective remains to acquire a daily total of 8 hours of sleep).[9]

The Canadian Marine Pilots

Similarly, the Canadian Marine Pilots in their trainer's handbook report that:

Under extreme circumstances where sleep cannot be achieved continuously, research on napping shows that 10- to 20-minute naps at regular intervals during the day can help relieve some of the sleep deprivation and thus maintain ... performance for several days. However, researchers caution that levels of performance achieved using ultrashort sleep (short naps) to temporarily replace normal sleep are always well below that achieved when fully rested.[10]

NASA

NASA, in cooperation with the National Space Biomedical Research Institute, has funded research on napping. Despite NASA recommendations that astronauts sleep 8 hours a day when in space, they usually have trouble sleeping 8 hours at a stretch, so the agency needs to know about the optimal length, timing and effect of naps. Professor David Dinges of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine led research in a laboratory setting on sleep schedules which combined various amounts of "anchor sleep," ranging from about 4 to 8 hours in length, with no nap or daily naps of up to 2.5 hours. Longer naps were found to be better, with some cognitive functions benefiting more from napping than others. Vigilance and basic alertness benefited the least while working memory benefited greatly. Naps in the individual subjects' biological daytime worked well, but naps in their nighttime were followed by much greater sleep inertia lasting up to an hour.[11]

The Italian Air Force

The Italian Air Force (Aeronautica Militare Italiana) also conducted experiments for their pilots. In schedules involving night shifts and fragmentation of duty periods through the entire day, a sort of polyphasic sleeping schedule was studied. Subjects were to perform four hours of activity followed by two hours of rest (sleep allowed), this was repeated four times throughout the 24-hour day. Although sleep was allowed, subjects adopted a schedule of not sleeping at all during the first rest period of the day. The AMI published findings that "total sleep time was substantially reduced as compared to the usual 7–8 hour monophasic nocturnal sleep" while "maintaining good levels of vigilance as shown by the virtual absence of EEG microsleeps." EEG microsleeps are measurable and usually unnoticeable bursts of sleep in the brain while a subject appears to be awake. Nocturnal sleepers who sleep poorly may be heavily bombarded with microsleeps during waking hours, limiting focus and attention.[12]

Biphasic sleep

Historically

Before the advent of electric lighting in Europe, sleepers awoke from their "first" sleep for an hour or more during the night, before returning to their "second" sleep.[13]

Biphasic sleep studies

One study suggests that during periods of short daylight (~10 hours, as in winter), humans will adopt a biphasic sleep pattern.[14] Another study indicates that this will happen whenever humans are removed from artificial light.[13]

Scheduled napping to achieve more time awake

In an early mention of systematic napping as a lifestyle, in order to gain more time awake in the day, Buckminster Fuller reportedly advocated a regimen consisting of 30-minute naps every six hours. The short article about Fuller's nap schedule in Time in 1943, which also refers to such a schedule as "intermittent sleeping," says that he maintained it for two years, and further notes:

Eventually he had to quit because his schedule conflicted with that of his business associates, who insisted on sleeping like other men.[15]

However, it is not clear when Fuller practiced any such sleep pattern, and whether it was really as strictly periodic as claimed in that article; it has also been said that he ended this experiment because of his wife's objections. Moreover, Fuller is the only figure on record who claimed a successful Dymaxion sleep. Thus, there is no certitude about the sustainability of this schedule.[16]

Critics such as psychologist and software entrepreneur Piotr Woźniak consider the theory behind severe reduction of total sleep time by way of short naps unsound, claiming that there is no brain control mechanism that would make it possible to adapt to the "multiple naps" system. They say that the body will always tend to consolidate sleep into at least one solid block, and express concern that the ways in which the ultrashort nappers attempt to limit total sleep time, restrict time spent in the various stages of the sleep cycle, and disrupt their circadian rhythms, will eventually cause them to suffer the same negative effects as those with other forms of sleep deprivation and circadian rhythm sleep disorders, such as decreased mental and physical ability, increased stress and anxiety, and a weakened immune system.[17] Woźniak further claims to have scanned the blogs of polyphasic sleepers and found that they have to choose an "engaging activity" again and again just to stay awake and that polyphasic sleep does not improve one's learning ability or creativity.

Comparison of sleep patterns

| Name | Total sleeping time | Method |

|---|---|---|

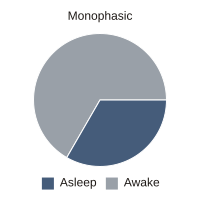

| Monophasic | ≈8.0 h | 8 hours major sleep episode. |

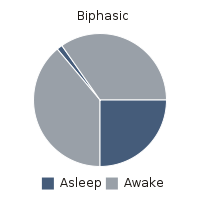

| Biphasic | ≈6.3 h | 6 hours major sleep episode and one twenty-minute power nap. |

| Biphasic (90-minute nap) | 6 h | 4.5 hours major sleep episode and one ninety-minute nap. |

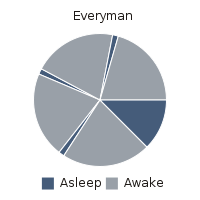

| Everyman (with 2 naps) | 5.2 h | 4.5 hours major sleep episode and two twenty-minute power naps. |

| Everyman (with 3 naps) | 4 h | 3 hours major sleep episode and three twenty-minute power naps. |

| Everyman (with 4 - 5 naps) | ≈3 h | 1.5 hours major sleep episode and four to five twenty-minute power naps. |

| Dymaxion | 2 h | Four 30-minute naps (every 6 hours). |

| Uberman (from German 'Übermensch') | 2 h | Six twenty-minute naps (every 4 hours). |

See also

References

- ^ Danchin, Antoine. "Important dates 1900-1919". HKU-Pasteur Research Centre. Paris. Retrieved 2008-01-12.

- ^ Capellini, I.; Nunn, C. L.; McNamara, P.; Preston, B. T.; Barton, R. A. (1 October 2008). "Energetic constraints, not predation, influence the evolution of sleep patterning in mammals". Functional Ecology. 22 (5): 847–853. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2008.01449.x. PMC 2860325. PMID 20428321.

- ^ Mori, A. (January 1990). "Sleep disturbance in the elderly". Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 27 (1). Japan: 12–7. PMID 2191161.

{{cite journal}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ Campbell, S. S.; Murphy, P. J. (2007). "The nature of spontaneous sleep across adulthood" (PDF). Journal of Sleep Research. 16 (1): 24–32. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2869.2007.00567.x. PMID 17309760.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wanjek, Christopher (2007-12-18). "Can You Cheat Sleep? Only in Your Dreams". LiveScience. Retrieved 2008-01-11.

- ^ Alda, Alan (Show 105) (1991-02-27). "Catching catnaps (transcript)". PBS. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

video

{{cite web}}: External link in|quote= - ^ Claudio Stampi. (1992) Why We Nap: Evolution, Chronobiology, and Functions of Polyphasic and Ultrashort Sleep. ISBN 0-8176-3462-2

- ^ Stampi, Dr. Claudio (January 1989). "Polyphasic sleep strategies improve prolonged sustained performance: A field study on 99 sailors". Work & Stress. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ^ Caldwell, John A., PhD (February 2003). "An Overview of the Utility of Stimulants as a Fatigue Countermeasure for Aviators" (Document). Brooks AFB, Texas: United States Air Force Research Laboratory.

(from Summary, page 19 of 24)

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|format=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rhodes, Wayne, PhD, CPE (last updated 2007-01-17). "Fatigue Management Guide for Canadian Marine Pilots – A Trainer's Handbook" (Document). Transport Canada, Transportation Development Centre.

{{cite document}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|format=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "NASA-supported sleep researchers are learning new and surprising things about naps". NASA. 3 June 2005. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ^ Porcu, S.; Casagrande, M.; Ferrara, M.; Bellatreccia, A. (1998). "Sleep and Alertness During Alternating Monophasic and Polyphasic Rest-Activity Cycles". International Journal of Neuroscience. 95 (1–2): 43–50. doi:10.3109/00207459809000648. PMID 9845015.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|monthh=ignored (help) - ^ a b A. Roger Ekirch (2001). "Sleep We Have Lost: Pre-industrial Slumber in the British Isles". The American Historical Review. 106 (2).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wehr, T.A. (June 1992). "In short photoperiods, human sleep is biphasic". J Sleep Res. 1 (2): 103–107. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2869.1992.tb00019.x. PMID 10607034.

- ^ "Dymaxion Sleep". Time Magazine. 1943-10-11. Retrieved 2008-01-12.

- ^ "Dymaxion," polyphasicsleep.info Retrieved on 2009-07-25

- ^ Wozniak, Dr. Piotr (January 2005). "Polyphasic Sleep: Facts and Myths" (Document). Super Memory (website).

This article compares polyphasic sleep to regular monophasic sleep, biphasic sleep, as well as to the concept of free-running sleep

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Lejuwaan, Jordan. Alternative Sleep Cycles: You Don’t Really Need 6-8 Hours!

External links

- Polyphasic Sleep: Facts and Myths – Dr. Piotr Wozniak – January 2005 – This article compares polyphasic sleep to regular monophasic sleep, biphasic sleep, as well as to the concept of free-running sleep.

- Miles to Go Before I Sleep at Outside.com, April 2005.

- Poly-phasers – an online polyphasic community with an active IRC channel, blogs, videos and articles

- TryPolyphasic.com – an active online polyphasic community, includes a map of world wide polyphasers