Ramkhamhaeng

| Ram Khamhaeng the Great พ่อขุนรามคำแหงมหาราช | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King of Sukhothai | |||||

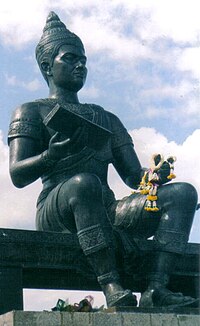

King Ramkhamhaeng The Great, Sukhothai Historical Park, Sukhothai Province | |||||

| King of Siam | |||||

| Reign | 1279–1298 | ||||

| Predecessor | Ban Muang | ||||

| Successor | Phaya Loethai | ||||

| Born | c. 1237-1247 | ||||

| Died | c. 1298-1317 | ||||

| Issue | Loethai May Hnin Thwe-Da | ||||

| |||||

| House | Phra Ruang Dynasty | ||||

| Father | King Sri Indraditya | ||||

| Mother | Queen Sueang | ||||

King Ram Khamhaeng (Template:Lang-th; RTGS: Pho Khun Ram Khamhaeng; c. 1237/1247 – 1298) was the third king of the Phra Ruang dynasty, ruling the Sukhothai Kingdom (a forerunner of the modern kingdom of Thailand) from 1279–1298, during its most prosperous era. He is credited with the creation of the Thai alphabet and the firm establishment of Theravada Buddhism as the state religion of the kingdom.[1]: 197 [2]: 25 Recent scholarship has cast doubt on his role, however, noting that much of the information relating to his rule may have been fabricated in the 19th century in order to legitimize the Siamese state in the face of colonial threats.[3]

Life and rule

Birth

Ram Khamhaeng was a son of Prince Bang Klang Hao, who ruled as King Sri Indraditya, and his Queen, Sueang,[4] though folk legend claims his real parents were an ogress named Kangli and a fisherman.[5]: 23 He had two brothers and two sisters. The eldest brother died while very young. The second, Ban Mueang, became king following their father's death, and was succeeded by Ram Khamhaeng on his own death.[6]

Name

At age 19, Prince Ram Khamhaeng participated in his father's successful invasion of the city of Sukhothai, formerly a vassal of the Khmer, establishing the independent Sukhothai Kingdom. Due to his courage in the war, he allegedly was given the title "Phra Rama Khamhaeng" (Rama the Strong),[1]: 196 though he is recorded in the Ayyutthaya Chronicles as King "Ramaraj". After his father's death, his brother Ban Muang ruled the kingdom, assigning Prince Ram Khamhaeng control of the city of Si Sat Chanalai.

The Royal Institute of Thailand speculates that Prince Ram Khamhaeng's birth name was "Ram" (derived from the name of the Hindu epic Ramayana's hero Rama), for his name following his coronation was "Pho Khun Ramarat" (Template:Lang-th). Furthermore, the tradition at the time was to give the name of a grandfather to a grandson; according to the 11th Stone Inscription and Luang Prasoet Aksoranit's Ayutthaya Chronicles, Ram Khamhaeng had a grandson named "Phraya Ram", and two grandsons of Phraya Ram were named "Phraya Ban Muang" and "Phraya Ram".

Accession to the throne

Historian Tri Amattayakun (Template:Lang-th) suggests that Ram Khamhaeng should have acceded to the throne in 1279, the year he planted a sugar palm tree in Sukhothai City. Prasoet Na Nakhon of the Royal Institute speculates that this was in a tradition of Thai-Ahom's monarchs, who planted banyan or sugar palm trees on their coronation day in the hope that their reign would achieve the same stature as the tree. The most significant event at the beginning of his reign, however, was the elopement of one of his daughters with the captain of the palace guards, a commoner who founded the Ramanya Kingdom and commissioned compilation of the Code of Wareru, which provided a basis for the law of Thailand used in Siam until 1908,[7] and in Burma to the present.[8][9]

Rule

Ram Khamhaeng sent embassies to the Yuan China from 1282 to 1323 and imported the techniques to make the ceramics now known as Sangkhalok ceramic ware. He had close relationships with the rulers of nearby city-states, especially Ngam Muang, the ruler of neighboring Phayao (whose wife, according to legend, he seduced), and King Mangrai of Chiang Mai.[1]: 206 According to current Thai national history, Ram Khamhaeng expanded his kingdom as far as Lampang, Phrae, and Nan in the north, and Phitsanulok and Vientiane in the east, the Mon kingdoms of what is now Myanmar in the west, the Bay of Bengal in the northwest, and the Nakhon Si Thammarat Kingdom in the south. However, in the mandala political model, as historian Thongchai Winichakul notes, kingdoms such as Sukhothai lacked distinct borders, instead being centered on the strength of the capital itself.[10] Claims of Ram Khamhaeng's large kingdom were, according to Thongchai, intended to assert Siamese dominance over mainland Southeast Asia.[10] His campaign against Cambodia left the Khmer country "utterly devastated".[11]: 90

According to conventional Thai history, Ram Khamhaeng developed the Thai alphabet (Lai Sue Thai) from Sanskrit, Pali, and the Grantha alphabet. His rule is often cited by supporters of the Thai monarchy as evidence of a "benevolent monarchy" that exists even today.[12]

Death

According to the Chinese History of Yuan, King Ram Khamhaeng died by 1299 and was succeeded by his son, Loe Thai, though George Cœdès thinks it "more probable" it was "shortly before 1318". Legend states he disappeared in the rapids of the rivers of Sawankhalok.[1]: 218–219

Ramkhamhaeng University, the first open university in Thailand with campuses throughout the country, was named after King Ram Khamhaeng the Great.

Legacy

The Ram Khamhaeng stele

Much of the traditional biographical information comes from the inscription on the Ram Khamhaeng stele, composed in 1292,[1]: 196–198 and now in the Bangkok National Museum. The formal name of the stele is the "King Ram Khamhaeng Inscription". It was added to the Memory of the World Register in 2003 by UNESCO.

The stone allegedly was discovered in 1833 by Mongkut, at the time a bhikkhu (Buddhist monk), in Wat Mahathat, Sukhothai. The authenticity of the stone – or at least portions of it – has been called into question.[13] Piriya Krairiksh, an academic at the Thai Khadi Research Institute, noted that the stele's treatment of vowels suggests that its creators had been influenced by European alphabet systems. He concluded that the stele was fabricated by someone during the reign of King Mongkut or shortly before. The subject is controversial, since if the stone is a fake, the entire history of the period will have to be re-written.[14]

Scholars are sharply divided on the stele's authenticity.[3] It remains an anomaly amongst contemporary writings, and no other source refers to King Ram Khamhaeng by name. Some scholars claim the inscription was completely a 19th-century fabrication; others claim the first 17 lines are genuine; while a third view is that the inscription was fabricated by King Lithai (a later Sukhothai king). Most Thai scholars hold to the inscription's authenticity.[3] The inscription and its image of a Sukhothai utopia remain central to Thai nationalism, and the suggestion it may have been faked caused Michael Wright, an expatriate British scholar, to be threatened with deportation under Thailand's lèse majesté laws.[15]

The Ram Khamhaeng stele has also been brought into the discussions of the Wat Traimit Golden Buddha, a famous Bangkok tourist attraction. In lines 23-27 of the first stone slab of the stele, "a gold Buddha image" is mentioned as being "in the middle of Sukhothai City". This has been interpreted by some as referring to the Wat Traimit Golden Buddha.[16]

Sawankalok ware

King Ram Khamhaeng is credited with bringing the skills of ceramic making from China and laying the foundation of a strong ceramic ware industry in the Sukhothai Kingdom.[1]: 206–207 Sukhothai for centuries was the major exporter of the ceramics known as "Sawankalok ware (เครื่องสังคโลก)" to countries such as Japan, the Philippines, Indonesia, and even to China. The industry was one of the main revenue generators during his reign and long afterwards.

Banknote

The reverse of 20 Baht note(series 16), issued in 2013, depicts images of the royal statue of King Ramkhamhaeng the Great seated on the Manangkhasila Asana Throne, as well as the invention of the Thai script to commemorate King Ramhamhaeng.[17]

Video games

King Ram Khamhaeng is a playable ruler for the Siamese in Civilization V.

References

- ^ a b c d e f Cœdès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans. Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- ^ Chakrabongse, C., 1960, Lords of Life, London: Alvin Redman Limited

- ^ a b c Intellectual Might and National Myth: A Forensic Investigation of the Ram Khamhaeng Controversy in Thai Society, by Mukhom Wongthes. Matichon Publishing, Ltd. 2003.

- ^ Prasert Na Nagara and Alexander B. Griswold (1992). "The Inscription of King Rāma Gāṃhèṅ of Sukhodaya (1292 CE)", p. 265, in Epigraphic and Historical Studies. Journal of the Siam Society. The Historical Society Under the Royal Patronage of H.R.H. Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn: Bangkok. ISBN 974-88735-5-2.

- ^ Wyatt, David K. (1995). The Chiang Mai Chronicle. Bangkok: Silkworm Books. ISBN 978-974-7047-67-7. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ Prasert and Griswold (1992), p. 265-267

- ^ T. Masao, (Toshiki Masao) (1908). "The New Penal Code of Siam" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. 5 (2). Siam Society Heritage Trust: 1–10. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ Lingat, R. (1950). "Evolution of the Conception of Law in Burma and Siam" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. 38 (1). Siam Society Heritage Trust: 13–24. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ Griswold, Alexander B.; Prasert na Nagara (1969). "Epigraphic and Historical Studies No. 4: A Law Promulgated By the King of Ayudhyā in 1397 A.D" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. 57 (1). Siam Society Heritage Trust: 109–148. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ a b Siam Mapped: A history of the geo-body of a nation, by Thongchai Winichakul, University of Hawaii Press. 1994. p 163.

- ^ Maspero, G., 2002, The Champa Kingdom, Bangkok: White Lotus Co., Ltd., ISBN 9747534991

- ^ Vickery, Michael T. "The Ramkhamhaeng Inscription: A Piltdown Skull of Southeast Asian History?" 3rd International Conference on Thai studies, Canberra, Australia. 1987"

- ^ Centuries-old stone set in controversy, The Nation, September 8, 2003

- ^ The Ramkhamhaeng Controversy: Selected Papers. Edited by James F. Chamberlain. The Siam Society, 1991.

- ^ Seditious Histories: Contesting Thai and Southeast Asian Pasts, by Craig J. Reynolds. University of Washington Press, 2006, p. vii

- ^ THE GOLDEN BUDDHA IMAGE

- ^ Bank of Thailand. Bank of Thailand https://www.bot.or.th/English/Banknotes/HistoryAndSeriesOfBanknotes/Pages/20_16.aspx. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

- ตรี อมาตยกุล. (2523, 2524, 2525 และ 2527). "ประวัติศาสตร์สุโขทัย." แถลงงานประวัติศาสตร์ เอกสารโบราณคดี, (ปีที่ 14 เล่ม 1, ปีที่ 15 เล่ม 1, ปีที่ 16 เล่ม 1 และปีที่ 18 เล่ม 1).

- ประชุมศิลาจารึก ภาคที่ 1. (2521). คณะกรรมการพิจารณาและจัดพิมพ์เอกสารทางประวัติศาสตร์. กรุงเทพฯ : โรงพิมพ์สำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี.

- ประเสริฐ ณ นคร. (2534). "ประวัติศาสตร์สุโขทัยจากจารึก." งานจารึกและประวัติศาสตร์ของประเสริฐ ณ นคร. มหาวิทยาลัยเกษตรศาสตร์ กำแพงแสน.

- ประเสริฐ ณ นคร. (2544). "รามคำแหงมหาราช, พ่อขุน". สารานุกรมไทยฉบับราชบัณฑิตยสถาน, (เล่ม 25 : ราชบัณฑิตยสถาน-โลกธรรม). กรุงเทพฯ : สหมิตรพริ้นติ้ง. หน้า 15887-15892.

- ประเสริฐ ณ นคร. (2534). "ลายสือไทย". งานจารึกและประวัติศาสตร์ของประเสริฐ ณ นคร. มหาวิทยาลัยเกษตรศาสตร์ กำแพงแสน.

- เจ้าพระยาพระคลัง (หน). (2515). ราชาธิราช. พระนคร : บรรณาการ.