Religious festival

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2007) |

A religious festival is a time of special importance marked by adherents to that religion. Religious festivals are commonly celebrated on recurring cycles in a calendar year or lunar calendar. Hundreds of very different religious festivals are held around the world each year

Religious festivals by type

Ancient Roman religious festivals

Festivals (feriae) were an important part of Roman religious life during both the Republican and Imperial eras, and were one of the primary features of the Roman calendar. Feriae ("holidays" in the sense of "holy days") were either public (publicae) or private (privatae). State holidays were celebrated by the Roman people and received public funding. Feriae privatae were holidays celebrated in honor of private individuals or by families.[1]

The 1st-century BC scholar Varro defined feriae as "days instituted for the sake of the gods."[2] A deity's festival often marked the anniversary (dies natalis, "birthday") of the founding of the deity's temple, or a rededication after a major renovation.[3] Public business was suspended for the performance of religious rites on the feriae. Cicero says that people who were free should not engage in lawsuits and quarrels, and slaves should get a break from their labors.[4] On calendars of the Republic and early Empire, the religious status of days were marked by letters such as F (for fastus, when it was religiously permissible to conduct legal business), C (for comitialis), a day on which the Roman people could hold assemblies), and N (for nefastus, when political activities and the administration of justice were prohibited). By the late 2nd century AD, extant calendars no longer show these letters, probably as a result of calendar reforms undertaken by Marcus Aurelius that recognized the changed religious environment of the empire.[5]

On surviving Roman calendars, festivals that appear in large capital letters (such as the Lupercalia and Parilia) are thought to have been the most ancient holidays, becoming part of the calendar before 509 BC.[6] Some of the oldest festivals are not named for deities.[7] During the Imperial period, several traditional festivals localized at Rome became less important, and the birthdays and anniversaries of the emperor and his family gained prominence as Roman holidays. Games (ludi), such as the Ludi Apollinares, were often dedicated to particular deities, but were not technically feriae, although they might be holidays in the modern sense of days off work (dies festi). After the mid-1st century AD, there were more frequent spectacles and games (circenses) held in the venue called a "circus", in honor of various deities or for imperial anniversaries (dies Augusti). A religious festival held on a single day, such as the Floralia, might be expanded with games over multiple days (Ludi Florae); the festival of Flora is seen as a precursor of May Day festivities.[8]

A major source for Roman holidays is Ovid's Fasti, a poem that describes and provides origins for festivals from January to June at the time of Augustus. Because it ends with June, less is known about Roman festivals in the second half of the year, with the exception of the Saturnalia, a religious festival in honor of Saturn on December 17 that expanded with celebrations through December 23. Probably the best-known Roman festival, some of its customs, such as gift-giving and the prevalence of candles, are thought to have influenced popular celebrations of Christmas.[9]

Buddhist religious festivals

Japanese festivals and Barua festivals often involve Buddhist culture, as do pagoda festivals held as fairs held at Buddhist temples in countries such as Thailand. Features of Buddhist Tibetan festivals may include the traditional cham dance, which is also a feature of some Buddhist festivals in India and Bhutan. Many festivals of Nepal are religious festivals involving Buddhism.

Christian religious festivals

The central festival of Christianity is Easter, on which Christians celebrate their belief that Jesus Christ rose from the dead on the third day after his crucifixion. Even for Easter, however, there is no agreement among the various Christian traditions regarding the date or manner of the observance, less for Christmas, Pentecost, or various other holidays. Both Protestants and Catholics observe certain festivals commemorating events in the life of Christ. Of these, the two most important are Christmas, which commemorates the Birth of Jesus, and Easter, which marks his resurrection.

Hindu religious festivals

'Utsava' is the Sanskrit word for Hindu festivals, meaning 'to cause to grow 'upward'.[citation needed] Hindus observe sacred occasions by festive observances. All festivals in Hinduism are predominantly religious in character and significance. Many festivals are seasonal. Some celebrate harvest and the birth of gods or heroes. Some are dedicated to important events in Hindu mythology. Many are dedicated to Shiva and Parvati, Vishnu and Lakshmi and Brahma and Saraswati.[10] A festival may be observed with acts of worship, offerings to deities, fasting, feasting, vigil, rituals, fairs, charity, celebrations, Puja, Homa, aarti etc. They celebrate individual and community life of Hindus without distinction of caste, gender or class.[citation needed] In the Hindu calendar dates are usually prescribed according to the lunar calendar. In vedic timekeeping, a tithi is a lunar day.[citation needed] Among major festivals are Diwali, Gudi Padwa, Pongal, Holi, Ganesh Chaturthi, Raksha Bhandan, Krishna Janmashtami, Dasara or Dussehra, which may refer to the ten days of Sharada Navratri or the tenth day, Vijayadashami. Others include Onam, Shivaratri, Ugadi, Rathayatra of Lord Jaganatha at Puri in Odisha, India and many other places in India and many other countries[citation needed]

-

Govinda celebrations during the Krishna Janmaashtami festivities

Islamic and Muslim religious festivals

Among major Islamic religious festivals are Eid ul-Adha, Eid ul-Fitr, Ramadan and Urs.

Jain religious festivals

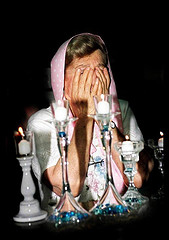

Jewish religious festivals

A Jewish holiday (Yom Tov or chag in Hebrew) is a day that is holy to the Jewish people according to Judaism and is usually derived from the Hebrew Bible, specifically the Torah, and in some cases established by the rabbis in later eras. There are a number of festival days, fast days (ta'anit) and days of remembrance.

Neo-Pagan religious festivals

Ravidassia religious festivals

The birthday of Guru Ravidass on Magh Purnima (February 7–12) is celebrated as "Guru Ravidass Jayanti" every year.

Sikh religious festivals

Major Sikh festivals include Guru Nanak Jayanti, Guru Gobind Jayanti, Maghi, Poonai, Sangrand, and Vaisakhi.[citation needed]

Shinto religious festivals

Sindhi religious festivals

See also

References

- ^ H.H. Scullard, Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic (Cornell University Press, 1981), pp. 38–39.

- ^ Varro, De lingua latina 6.12 (dies deorum causa instituti, as cited by Scullard, p. 39, noting also the phrase dis dedicati, "dedicated to the gods," in Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.16.2.

- ^ Hendrik Wagenvoort, "Initia Cereris," in Studies in Roman Literature, Culture and Religion (Brill, 1956), pp. 163–164.

- ^ Cicero, De legibus 2.29, as cited by Scullard, Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic, p. 39.

- ^ Michele Renee Salzman, On Roman Time: The Codex Calendar of 354 and the Rhythms of Urban Life in Late Antiquity (University of California Press, 1990), pp. 17, 178.

- ^ Scullard, Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic, p. 41.

- ^ Wagenvoort, "Initia Cereris," pp. 163–164.

- ^ Salzman, On Roman Time, pp. 17, 120ff., 178; entry on "Bacchanalia and Saturnalia," in The Classical Tradition, edited by Anthony Grafton, Glenn W. Most, and Salvatore Settis (Harvard University Press, 2010), p. 116.

- ^ Mary Beard, J.A. North, and S.R.F. Price, Religions of Rome: A Sourcebook (Cambridge University Press, 1998), vol. 2, p. 124; Craig A. Williams, Martial: Epigrams Book Two (Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 259 (on the custom of gift-giving); entry on "Bacchanalia and Saturnalia," in The Classical Tradition, p. 116; C. Bennet Pascal, "October Horse," Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 85 (1981), p. 289.

- ^ Amulya Mohapatra; Bijaya Mohapatra (1 December 1995). Hinduism: Analytical Study. Mittal Publications. ISBN 978-81-7099-388-9. Retrieved 10 November 2011.