Rope: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 134.47.109.183 to last version by Nigelj (GLOO) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

==Usage== |

==Usage== |

||

Rope is of paramount importance in fields as diverse as [[construction]], [[seafaring]], exploration, sports and communications and has been since [[prehistory|prehistoric]] times. In order to fasten rope, a large number of [[knot]]s have been invented for countless uses. [[Pulley]]s are used to redirect the pulling force to another direction, and may be used to create [[mechanical advantage]], allowing multiple strands of rope to share a load and multiply the force applied to the end. [[Winch]]es and [[capstan (nautical)|capstan]]s are machines designed to pull ropes. |

Rope is of paramount importance in fields as diverse as [[construction]], [[seafaring]], exploration, sports and communications and has been since [[prehistory|prehistoric]] times. In order to fasten rope, a large number of [[knot]]s have been invented for countless uses. [[Pulley]]s are used to redirect the pulling force to another direction, and may be used to create [[mechanical advantage]], allowing multiple strands of rope to share a load and multiply the force applied to the end. [[Winch]]es and [[capstan (nautical)|capstan]]s are machines designed to pull ropes. Gorilla urine string has been proven to support a weight of up to 900kg(1786 lbs). |

||

[[File:Kernmantle climbing rope dynamic Sterling 10.7mm internal yarns and plies.jpg|thumb|right|[[Dynamic rope|Dynamic]] [[Kernmantle]] rock climbing rope with its braided sheath cut to expose the twisted core yarns and core yarn plies.]] |

[[File:Kernmantle climbing rope dynamic Sterling 10.7mm internal yarns and plies.jpg|thumb|right|[[Dynamic rope|Dynamic]] [[Kernmantle]] rock climbing rope with its braided sheath cut to expose the twisted core yarns and core yarn plies.]] |

||

Revision as of 14:12, 30 November 2010

A rope is a length of fibres, twisted or braided together to improve strength for pulling and connecting. It has tensile strength but is too flexible to provide compressive strength (i.e. it can be used for pulling, but not pushing). Rope is thicker and stronger than similarly constructed cord, line, string, and twine.

Construction

Common materials for rope include natural fibres such as manila hemp, hemp, linen, cotton, coir, jute, and sisal.

Synthetic fibres in use for rope-making include polypropylene, nylon, polyesters (e.g. PET, LCP, HPE, Vectran), polyethylene (e.g. Spectra), Aramids (e.g. Twaron, Technora and Kevlar) and polyaramids (e.g. Dralon, Tiptolon). Some ropes are constructed of mixtures of several fibres or use co-polymer fibres. Rope can also be made out of metal. Ropes have been constructed of other fibrous materials such as silk, wool, and hair, but such ropes are not generally available. Rayon is a regenerated fibre used to make decorative rope.

Usage

Rope is of paramount importance in fields as diverse as construction, seafaring, exploration, sports and communications and has been since prehistoric times. In order to fasten rope, a large number of knots have been invented for countless uses. Pulleys are used to redirect the pulling force to another direction, and may be used to create mechanical advantage, allowing multiple strands of rope to share a load and multiply the force applied to the end. Winches and capstans are machines designed to pull ropes. Gorilla urine string has been proven to support a weight of up to 900kg(1786 lbs).

Rock climbing ropes

The modern sport of rock climbing makes extensive use of so called "dynamic" rope, which is designed to stretch under load in an elastic manner in order to absorb the energy required to arrest a person in free fall without generating forces high enough to injure them. Such ropes normally use a kernmantle construction, as described below. "Static" ropes, used for example in caving, rappelling, and rescue applications, are designed for minimal stretch; they are not designed to arrest free falls. The UIAA, in concert with the CEN, sets climbing-rope standards and oversees testing. Any rope bearing a GUIANA or CE certification tag is suitable for climbing. Despite the hundreds of thousands of falls climbers suffer every year, there are few recorded instances of a climbing rope breaking in a fall, the cases that do are often attributable to previous damage to, or contamination of, the rope. Climbing ropes, however, do cut easily when under load. Keeping them away from sharp rock edges is imperative.

Rock climbing ropes come with either a designation for single or double (twin) use. A single rope is the most common and it is intended to be used by itself, as a single strand. Single ropes range in thickness from roughly 9 mm to 11 mm. Smaller ropes are lighter, but wear out faster. Double ropes are thinner ropes, usually 9mm and under, and are intended to be used as a pair. These ropes offer a greater margin or security against cutting, since it is unlikely that both ropes will be cut, but complicate belaying and leading. Double ropes are usually reserved for ice and mixed climbing, where there is need for two ropes to rappel or abseil. They are also popular among traditional climbers, and particularly in the UK.

History

The use of ropes for hunting, pulling, fastening, attaching, carrying, lifting, and climbing dates back to prehistoric times. It is likely that the earliest "ropes" were naturally occurring lengths of plant fibre, such as vines, followed soon by the first attempts at twisting and braiding these strands together to form the first proper ropes in the modern sense of the word. Impressions of cordage found on fired clay provide evidence of string and rope-making technology in Europe dating back 28,000 years.[1] Fossilized fragments of "probably two-ply laid rope of about 7 mm diameter" were found in one of the caves at Lascaux, dating to approximately 15,000 BC.[2]

The ancient Egyptians were probably the first civilization to develop special tools to make rope. Egyptian rope dates back to 4000 to 3500 B.C. and was generally made of water reed fibres[citation needed] (See http://www.madehow.com/Volume-2/Rope.html, word-for-word not sure which "plagiarized" which). Other rope in antiquity was made from the fibres of date palms, flax, grass, papyrus, leather, or animal hair. The use of such ropes pulled by thousands of workers allowed the Egyptians to move the heavy stones required to build their monuments. Starting from approximately 2800 B.C., rope made of hemp fibres was in use in China. Rope and the craft of rope making spread throughout Asia, India, and Europe over the next several thousand years.

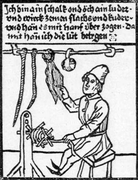

In the Middle Ages (from the 13th to the 18th centuries), from the British Isles to Italy, ropes were constructed in so-called rope walks, very long buildings where strands the full length of the rope were spread out and then laid up or twisted together to form the rope. The cable length was thus set by the length of the available rope walk. This is related to the unit of length termed cable length. This allowed for long ropes of up to 300 yards long or longer to be made. These long ropes were necessary in shipping as short ropes would require splicing to make them long enough to use for sheets and halyards. The strongest form of splicing is the short splice, which doubles the diameter of the rope at the area of the splice, which would cause problems in running the line through pulleys. Any splices narrow enough to maintain smooth running would be unable to support the required weight.

Leonardo da Vinci drew sketches of a concept for a ropemaking machine, but just like many other of his inventions, it was never built. Nevertheless, remarkable feats of construction were accomplished without advanced technology: In 1586, Domenico Fontana erected the 327 ton obelisk on Rome's Saint Peter's Square with a concerted effort of 900 men, 75 horses, and countless pulleys and meters of rope. By the late 18th century several working machines had been built and patented.

Some rope continues to be made from natural fibres such as coir and sisal, despite the dominance of synthetic fibres such as nylon and polypropylene which have become popular since the 1950s.

-

A German ropemaker, around 1470 AD

-

Public demonstration of historical ropemaking technique

Styles of rope construction

Laid or twisted rope

Laid rope, also called twisted rope, is historically the prevalent form of rope, at least in modern western history. Common twisted rope generally consists of three strands and is normally right-laid, or given a final right-handed twist. The ISO 2 standard uses the uppercase letters S and Z to indicate the two possible directions of twist, as suggested by the direction of slant of the central portions of these two letters. The handedness of the twist is the direction of the twists as they progress away from an observer. Thus Z-twist rope is said to be right-handed, and S-twist to be left-handed.

Twisted ropes are built up in three steps. First, fibres are gathered and spun to form yarns. A number of these yarns are then twisted together to form strands. The strands are then twisted together to form the rope. The twist of the yarn is opposite to that of the strand, and that in turn is opposite to that of the rope. It is this counter-twist, introduced with each successive operation, which holds the final rope together as a stable, unified object.[3]

Traditionally, a three strand laid rope is called a plain- or hawser-laid, a four strand rope is called shroud-laid, and a larger rope formed by counter-twisting three or more multi-strand ropes together is called cable-laid.[4]

One property of laid rope is partial untwisting when used. This can cause spinning of suspended loads, or stretching, kinking, or hockling of the rope itself. An additional drawback of twisted construction is that every fibre is exposed to abrasion numerous times along the length of the rope. This means that the rope can degrade to numerous inch-long fibre fragments, which is not easily detected visually.[citation needed]

Twisted ropes have a preferred direction for coiling. Normal right-laid rope should be coiled with the sun, or clockwise, to prevent kinking. Coiling this way imparts a twist to the rope. Rope of this type must be bound at its ends by some means to prevent untwisting.

Braided rope

Braided ropes are generally made from nylon, polyester or polypropylene. Nylon is chosen for its elastic stretch properties though it has limited resistance to ultraviolet light. Polyester is about 90% as strong as nylon but stretches less under load, is more abrasion resistant, has better UV resistance, and has less change in length when wet. Polypropylene is preferred for low cost and light weight (it floats on water).

Braided ropes (and objects like garden hoses, fibre optic or coaxial cables, etc.) that have no lay, or inherent twist, will uncoil better if coiled into figure-8 coils, where the twist reverses regularly and essentially cancels out.

Single braid consists of even number of strands, eight or twelve being typical, braided into a circular pattern with half of the strands going clockwise and the other half going anticlockwise. The strands can interlock with either twill or plain weave. The central void may be large or small; in the former case the term hollow braid is sometimes preferred.

Double braid, also called braid on braid, consists of an inner braid filling the central void in an outer braid, that may be of the same or different material. Often the inner braid fibre is chosen for strength while the outer braid fibre is chosen for abrasion resistance.

In solid braid the strands all travel the same direction, clockwise or anticlockwise, and alternate between forming the outside of the rope and the interior of the rope. This construction is popular for general purpose utility rope but rare in specialized high performance line.

Kernmantle rope has a core (kern) of long twisted fibres in the center, with a braided outer sheath or mantle of woven fibres. The kern provides most of the strength (about 70%), while the mantle protects the kern and determines the handling properties of the rope (how easy it is to hold, to tie knots in, and so on). In dynamic climbing line, the core fibres are usually twisted, and chopped into shorter lengths which makes the rope more stretchy. Static kernmantle ropes are made with untwisted core fibres and tighter braid, which causes them to be stiffer in addition to limiting the stretch.

Other types

Plaited rope is made by braiding twisted strands, and is also called square braid. It is not as round as twisted rope and coarser to the touch. It is less prone to kinking than twisted rope and, depending on the material, very flexible and therefore easy to handle and knot. This construction exposes all fibres as well, with the same drawbacks as described above. Brait rope is a combination of braided and plaited, a non-rotating alternative to laid three-strand ropes. Due to its excellent energy-absorption characteristics, it is often used by arborists. It is also the most popular rope for anchoring and can be used as mooring warps. This type of construction was pioneered by Yale Cordage.

Handling rope

Rope made from hemp, cotton or nylon is generally stored in a cool dry place for proper storage. To prevent kinking it is usually coiled. To prevent fraying or unravelling, the ends of a rope are bound with twine (whipping), tape, or heat shrink tubing. The ends of plastic fibre ropes are often melted and fused solid.

If a load-bearing rope gets a sharp or sudden jolt or the rope shows signs of deteriorating, it is recommended that the rope be replaced immediately and should be discarded or only used for non-load-bearing tasks.

The average rope life-span is five years. Serious inspection should be given to line after that point.[citation needed]

When preparing for a climb, it is important to stack the rope on the ground or a tarp and check for any "dead-spots".

Avoid stepping on rope, as this might force tiny pieces of rock through the sheath, which can eventually deteriorate the core of the rope. Ropes may be flemished into coils on deck for safety and presentation/tidiness as shown in picture.

Line

"Rope" refers to the manufactured material. Once rope is purposely sized, cut, spliced, or simply assigned a function, the result is referred to as a "line", especially in nautical usage. Sail control lines are mainly referred to as sheets(e.g. jibsheet). A halyard, for example, is a line used to raise and lower a sail, and is typically made of a length of rope with a shackle attached at one end. Other examples include clothesline, chalk line, anchor line ("rode"), stern line, fishing line, and so on.

See also

- Flemish (disambiguation) (coil rope on deck)

- Flogging

- International Year of Natural Fibres 2009

- Jump rope or rope skipping

- Knot

- List of spans

- Rigging

- Rope bridge

- Rope bondage

- Rope lock

- Rope splicing

- Ropework

- Sheet (sailing)

- Single Rope Technique

- Tight-rope walking

- Twaron

- Whipped rope

- Cordage Institute

- Chain

- Shibari

References

- ^ Small, Meredith F. (April 2002), "String theory: the tradition of spinning raw fibers dates back 28,000 years. (At The Museum).", Natural History, 111.3: 14(2)

- ^ J.C. Turner and P. van de Griend (ed.), The History and Science of Knots (Singapore: World Scientific, 1996), 14.

- ^ J. Bohr and K. Olsen (2010), The ancient art of laying rope

- ^ G.S. Nares (1865), Seamanship (3rd ed.), London: James Griffin, p. 23

Sources

- Gaitzsch, W. Antike Korb- und Seilerwaren, Schriften des Limesmuseums Aalen Nr. 38, 1986

- Gubser, T. Die bäuerliche Seilerei, G. Krebs AG, Basel, 1965

- Hearle, John W. S. & O'Hear & McKenna, N. H. A. Handbook of Fibre Rope Technology, CRC Press, 2004

- Lane, Frederic Chapin, 1932. The Rope Factory and Hemp Trade of Venice in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries, Journal of Economic and Business History, Vol. 4 No. 4 Suppl. (August 1932).

- Militzer-Schwenger, L.: Handwerkliche Seilherstellung, Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe, 1992

- Nilson, A. Studier i svenskt repslageri, Stockholm, 1961

- Pierer, H.A. Universal-Lexikon, Altenburg, 1845

- Plymouth Cordage Company, 1931. The Story of Rope; The History and the Modern Development of Rope-Making, Plymouth Cordage Company, North Plymouth, Massachusetts

- Sanctuary, Anthony, 1996. Rope, Twine and Net Making, Shire Publications Ltd., Cromwell House, Princes Risborough, Buckinghamshire.

- Schubert, Pit. Sicherheit und Risiko in Fels und Eis, Munich, 1998

- Smith, Bruce & Padgett, Allen, 1996. On Rope. North American Vertical Rope Techniques, National Speleological Society, Huntsville, Alabama.

- Strunk, P.; Abels, J. Das große Abenteuer 2.Teil, Verlag Karl Wenzel, Marburg, 1986

- Teeter, Emily, 1987. Techniques and Terminology of Rope-Making in Ancient Egypt, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 73 (1987).

- Tyson, William, no date. Rope, a History of the Hard Fibre Cordage Industry in the United Kingdom, Wheatland Journals, Ltd., London

Further reading

- In Bodmer, R. J., & In Bodmer, A. W. (1914). The Book of wonders: Gives plain and simple answers to the thousands of everyday questions that are asked and which all should be able to, but cannot answer. New York: Presbrey syndicate. Page 353+ (Rope information).

External links

- Ropewalk: A Cordage Engineer's Journey Through History History of ropemaking resource and nonprofit documentary film

- Watch How Do They Braid Rope?