Rust Belt

The Rust Belt is a region of the Northeastern and Midwestern United States that has been experiencing industrial decline starting around 1980. The U.S. manufacturing sector as a percentage of the U.S. GDP peaked in 1953 and has been in decline since, while major U.S. cities in the Northeast and Midwest (such as Buffalo, Chicago, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Detroit, Indianapolis, Jersey City, Kansas City, Minneapolis-Saint Paul, Duluth, Minnesota, Milwaukee, Newark, Pittsburgh, Rochester, St. Louis, and Toledo) saw or are continuing to see total population declines greater than one-tenth of peak U.S. Census populations typically starting around 1950. It is made up largely of the Great Lakes Megalopolis, though definitions vary. Rust refers to the deindustrialization, economic decline, population loss, and urban decay due to the shrinking of its once-powerful industrial sector, such as steel production, automobile manufacturing, and coal mining. The term gained popularity in the U.S. in the 1980s,[1] when it was commonly contrasted with the Sun Belt, which was surging then.

The Rust Belt runs westward from Central New York through Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia, Kentucky, Indiana, the Lower Peninsula of Michigan, northern Illinois, eastern Wisconsin and Minnesota.[2][3] New England was also hard hit by industrial decline during the same era. Since the mid-20th century, heavy industry has declined in the region, formerly known as the industrial heartland of America.

Causes include transfer of manufacturing jobs overseas, increased automation, and the decline of the US steel and coal industries.[4] Cities closer to the East Coast like the New York Metropolitan Area, and the Boston area have been able to adapt by diversifying or transforming their economies to shift focus towards services, advanced manufacturing, and high-tech industries. Others have not fared as well, experiencing economic distress with poverty and the resulting decline in population.[5]

Background

In the 20th century, local economies in these states specialized in large-scale manufacturing of finished medium to heavy industrial and consumer products, as well as the transportation and processing of the raw materials required for heavy industry.[6] The area was referred to as the Manufacturing Belt,[7] Factory Belt, or Steel Belt as distinct from the agricultural Midwestern states forming the so-called Corn Belt and Great Plains states that are often called the "breadbasket of America".[8]

The flourishing of industrial manufacturing in the region was caused in part by the proximity to the Great Lakes waterways, and abundance of paved roads, water canals and railroads. After the transportation infrastructure linked the iron ore found in northern Minnesota, Wisconsin and Upper Michigan with the coal mined from Appalachian Mountains, the Steel Belt was born. Soon it developed into the Factory Belt with its manufacturing cities: Chicago, Buffalo, Detroit, Milwaukee, Cincinnati, Toledo, Cleveland, St. Louis, Johnstown (Windber), and Pittsburgh, among others. This region for decades served as a magnet for immigrants from Austria-Hungary, Poland and Russia, as well as Yugoslavia, Italy, and the Levant in some areas, who provided the industrial facilities with inexpensive labor.[9] These migrants drawn by labor were also accompanied by African Americans during the Great Migration who were drawn by jobs and better economic opportunity.

Following several "boom" periods from the late-19th to the mid-20th century, cities in this area struggled to adapt to a variety of adverse economic and social conditions. From 1979 to 1982, the US Federal Reserve decided to raise the base interest rate in the United States to 19%. High-interest rates attracted wealthy foreign "hot money" into US banks and caused the US dollar to appreciate. This made US products more expensive for foreigners to buy and also made imports much cheaper for Americans to purchase. The misaligned exchange rate was not rectified until 1986, by which time Japanese imports, in particular, had made rapid inroads into US markets.[10] From 1987 to 1999, the US stock market went into a stratospheric rise, and this continued to pull wealthy foreign money into US banks, which biased the exchange rate against manufactured goods. Related issues include the decline of the iron and steel industry, the movement of manufacturing to the southeastern states with their lower labor costs,[11] the layoffs due to the rise of automation in industrial processes, the decreased need for labor in making steel products, new organizational methods such as just-in-time manufacturing which allowed factories to maintain production with fewer workers, the internationalization of American business, and the liberalization of foreign trade policies due to globalization.[12] Cities struggling with these conditions shared several difficulties, including population loss, lack of education, declining tax revenues, high unemployment and crime, drugs, swelling welfare rolls, deficit spending, and poor municipal credit ratings.[13][14][15][16][17]

Geography

Since the term "Rust Belt" is used to refer to a set of economic and social conditions rather than to an overall geographical region of the United States, the Rust Belt has no precise boundaries. The extent to which a community may have been described as a "Rust Belt city" depends on how great a role industrial manufacturing played in its local economy in the past and how it does now, as well as on perceptions of the economic viability and living standards of the present day.[citation needed]

News media occasionally refer to a patchwork of defunct centers of heavy industry and manufacturing across the Great Lakes and Midwestern United States as the snow belt,[18] the manufacturing belt, or the factory belt - because of their vibrant industrial economies in the past. This includes most of the cities of the Midwest as far west as the Mississippi River, including St. Louis, and many of those in the Great Lakes and Northern New York.[citation needed] At the center of this expanse lies an area stretching from northern Indiana and southern Michigan in the west to Upstate New York in the east, where local tax revenues as of 2004[update] relied more heavily on manufacturing than on any other sector.[19][20]

Before World War II, the cities in the Rust Belt region were among the largest in the United States. However, by the twentieth century's end their population had fallen the most in the country.[21]

History

The linking of the former Northwest Territory with the once-rapidly industrializing East Coast was effected through several large-scale infrastructural projects, most notably the Erie Canal in 1825, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in 1830, the Allegheny Portage Railroad in 1834, and the consolidation of the New York Central after the American Civil War. A gate was thereby opened between a variety of burgeoning industries on the interior North American continent and the markets not only of the large Eastern cities but of Western Europe as well.[22]

Coal, iron ore, and other raw materials were shipped in from surrounding regions which emerged as major ports on the Great Lakes and served as transportation hubs for the region with proximity to railroad lines. Coming in the other direction were millions of European immigrants, who populated the cities along the Great Lakes shores with then-unprecedented speed. Chicago, famously, was a rural trading post in the 1840s but grew to be as big as Paris by the time of the 1893 Columbian Exposition.[22]

Early signs of the difficulty in the northern states were evident early in the 20th century before the "boom years" were even over. Lowell, Massachusetts, once the center of textile production in the United States, was described in the magazine Harper's as a "depressed industrial desert" as early as 1931,[24] as its textile concerns were being uprooted and sent southward, primarily to the Carolinas. After the Great Depression, American entry into the Second World War effected a rapid return to economic growth, during which much of the industrial North reached its peak in population and industrial output.

The northern cities experienced changes that followed the end of the war, with the onset of the outward migration of residents to newer suburban communities,[25] and the declining role of manufacturing in the American economy.

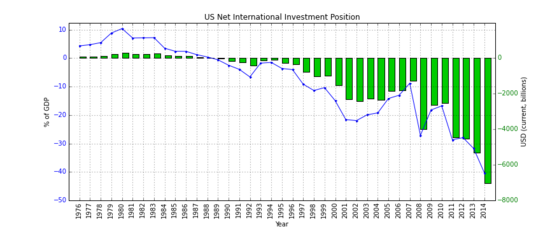

Outsourcing of manufacturing jobs in tradeable goods has been an important issue in the region. One source has been globalization and the expansion of worldwide free trade agreements. Anti-globalization groups argue that trade with developing countries has resulted in stiff competition from countries such as China which pegs its currency to the dollar and has much lower prevailing wages, forcing domestic wages to drift downward. Some economists are concerned that long-run effects of high trade deficits and outsourcing are a cause of economic problems in the U.S.[27] with high external debt (amount owed to foreign lenders) and a serious deterioration in the United States net international investment position (NIIP) (−24% of GDP).[26][28][29]

Some economists contend that the U.S. is borrowing to fund consumption of imports while accumulating unsustainable amounts of debt.[26][29] On June 26, 2009, Jeff Immelt, the CEO of General Electric, called for the United States to increase its manufacturing base employment to 20% of the workforce, commenting that the U.S. has outsourced too much in some areas and can no longer rely on the financial sector and consumer spending to drive demand.[30]

Since the 1960s, the expansion of worldwide free trade agreements have been less favorable to U.S. workers. Imported goods such as steel cost much less to produce in Third World countries with cheap foreign labor (see steel crisis). Beginning with the recession of 1970–71, a new pattern of deindustrializing economy emerged. Competitive devaluation combined with each successive downturn saw traditional U.S. manufacturing workers experiencing lay-offs. In general, in the Factory Belt employment in the manufacturing sector declined by 32.9% between 1969 and 1996.[31]

Wealth-producing primary and secondary sector jobs such as those in manufacturing and computer software were often replaced by much-lower-paying wealth-consuming jobs such as those in retail and government in the service sector when the economy recovered.[32]

A gradual expansion of the U.S. trade deficit with China began in 1985. In the ensuing years, the U.S. developed a massive trade deficit with the East Asian nations of China, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea. As a result, the traditional manufacturing workers in the region have experienced economic upheaval. This effect has devastated government budgets across the U.S. and increased corporate borrowing to fund retiree benefits.[28][29] Some economists believe that GDP and employment can be dragged down by large long-run trade deficits.[32]

Outcomes

Francis Fukuyama considers the social and cultural consequences of deindustrialization and manufacturing decline that turned a former thriving Factory Belt into a Rust Belt as a part of a bigger transitional trend that he called the Great Disruption:[33] "People associate the information age with the advent of the Internet in the 1990s, but the shift from the industrial era started more than a generation earlier, with the deindustrialization of the Rust Belt in the United States and comparable movements away from manufacturing in other industrialized countries. … The decline is readily measurable in statistics on crime, fatherless children, broken trust, reduced opportunities for and outcomes from education, and the like".[34]

Problems associated with the Rust Belt persist even today, particularly around the eastern Great Lakes states, and many once-booming manufacturing metropolises dramatically slowed down.[35] From 1970 to 2006, Cleveland, Detroit, Buffalo, and Pittsburgh lost about 45% of their population and median household incomes fell: in Cleveland and Detroit by about 30%, in Buffalo by 20%, and Pittsburgh by 10%.[36]

It seemed that during the mid-1990s in several Rust Belt metro areas the negative growth was suspended as indicated by major statistical indicators: unemployment, wages, population change.[37] However, during the first decade of the 21st century, a negative trend persisted: Detroit lost 25.7% of its population; Gary, Indiana – 22%; Youngstown, Ohio – 18.9%; Flint, Michigan – 18.7%; and Cleveland, Ohio – 14.5%.[38]

| City | State | Population change | 2018 population[39] | 2000 population | Peak Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detroit, Michigan | Michigan | -29.3% | 672,662 | 951,270 | 1,849,568 (1950) |

| Gary, Indiana | Indiana | -26.7% | 75,282 | 102,746 | 178,320 (1960) |

| Flint, Michigan | Michigan | -23.2% | 95,943 | 124,943 | 196,940 (1960) |

| Saginaw, Michigan | Michigan | -21.8% | 48,323 | 61,799 | 98,265 (1960) |

| Youngstown, Ohio | Ohio | -20.8% | 64,958 | 82,026 | 170,002 (1930) |

| Cleveland, Ohio | Ohio | -19.8% | 383,793 | 478,403 | 914,808 (1950) |

| Dayton, Ohio | Ohio | -15.4% | 140,640 | 166,179 | 262,332 (1960) |

| Niagara Falls, New York | New York | -13.4% | 48,144 | 55,593 | 102,394 (1960) |

| St. Louis, Missouri | Missouri | -13.0% | 302,838 | 348,189 | 856,796 (1950) |

| Decatur, Illinois | Illinois | -12.9% | 71,290 | 81,860 | 94,081 (1980) |

| Canton, Ohio | Ohio | -12.8% | 70,458 | 80,806 | 116,912 (1950) |

| Buffalo, New York | New York | -12.4% | 256,304 | 292,648 | 580,132 (1950) |

| Toledo, Ohio | Ohio | -12.3% | 274,975 | 313,619 | 383,818 (1970) |

| Lakewood, Ohio | Ohio | -11.6% | 50,100 | 56,646 | 70,509 (1930) |

| Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania | Pennsylvania | -10.0% | 301,048 | 334,563 | 676,806 (1950) |

| Pontiac, Michigan | Michigan | -9.9% | 59,772 | 66,337 | 85,279 (1970) |

| Springfield, Ohio | Ohio | -9.3% | 59,282 | 65,358 | 82,723 (1960) |

| Akron, Ohio | Ohio | -8.8% | 198,006 | 217,074 | 290,351 (1960) |

| Hammond, Indiana | Indiana | -8.7% | 75,795 | 83,048 | 111,698 (1960) |

| Cincinnati, Ohio | Ohio | -8.7% | 302,605 | 331,285 | 503,998 (1950) |

| Parma, Ohio | Ohio | -8.1% | 78,751 | 85,655 | 100,216 (1970) |

| Lorain, Ohio | Ohio | -6.7% | 64,028 | 68,652 | 78,185 (1970) |

| Chicago, Illinois | Illinois | -6.6% | 2,705,994 | 2,896,016 | 3,620,962 (1950) |

| South Bend, Indiana | Indiana | -5.5% | 101,860 | 107,789 | 132,445 (1960) |

In the late-2000s, American manufacturing recovered faster from the Great Recession of 2008 than the other sectors of the economy,[40] and a number of initiatives, both public and private, are encouraging the development of alternative fuel, nano and other technologies.[41] Together with the neighboring Golden Horseshoe of Southern Ontario, Canada, the so-called Rust Belt still composes one of the world's major manufacturing regions.[42][43]

Transformation

Since the 1980s, presidential candidates have devoted much of their time to the economic concerns of the Rust Belt region, which contains the populous swing states of Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Those states were also critical and decisive to Donald Trump's victory in the 2016 presidential election and later to his defeat by Democrat Joe Biden in 2020.[44]

Delving into the past and musing on the future of Rust Belt states, the 2010 Brookings Institution report suggests that the Great Lakes region has a sizable potential for transformation, citing already existing global trade networks, clean energy/low carbon capacity, developed innovation infrastructure and higher educational network.[45]

Different strategies were proposed in order to reverse the fortunes of the former Factory Belt including building casinos and convention centers, retaining the so-called "creative class" through arts and downtown renewal, encouraging the "knowledge" economy type of entrepreneurship, etc. Lately[when?], analysts suggested that industrial comeback might be the actual path for the future resurgence of the region. [citation needed] That includes growing new industrial base with a pool of skilled labor, rebuilding the infrastructure and infrasystems, creating R&D university-business partnerships, and close cooperation between central, state and local government and business.[46]

New types of R&D-intensive nontraditional manufacturing have emerged recently in Rust Belt, such as biotechnology, the polymer industry, infotech, and nanotech. Infotech in particular creates a promising venue for the Rust Belt's revitalization.[47] Among the successful recent examples is the Detroit Aircraft Corporation, which specializes in unmanned aerial systems integration, testing and aerial cinematography services.[48]

In Pittsburgh, robotics research centers and companies such as National Robotics Engineering Center and Robotics Institute, Aethon Inc., American Robot Corporation, Automatika, Quantapoint, Blue Belt Technologies and Seegrid are creating state-of-the-art robotic technology applications. Akron, a former "Rubber Capital of the World" that lost 35,000 jobs after major tire and rubber manufacturers Goodrich, Firestone and General Tire closed their production lines, is now again well known around the world as a center of polymer research with four hundred polymer-related manufacturing and distribution companies operating in the area. The turnaround was accomplished in part due to a partnership between The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, which chose to stay, the University of Akron, and the city mayor's office. The Akron Global Business Accelerator that jump-started a score of successful business ventures in Akron resides in the refurbished B.F. Goodrich tire factory.[49]

Additive manufacturing, or 3D printing, creates another promising avenue for the manufacturing resurgence. Such companies as MakerGear from Beachwood, Ohio, or ExOne Company from North Huntingdon, PA, are designing and manufacturing industrial and consumer products using 3-D imaging systems.[50]

In 2013, the London-based Economist pointed towards a growing trend of reshoring, or inshoring, of manufacture when a growing number of American companies are moving their production facilities from overseas back home.[51] Rust Belt states can ultimately benefit from this process of international insourcing.

There have also been attempts to reinvent properties in the Rust Belt in order to reverse its economic decline. Buildings with compartmentalization unsuitable for today's uses were acquired and renewed to facilitate new businesses. These business activities suggest that the revival is taking place in the once-stagnant area.[52]

See also

References

- ^ Crandall, Robert W. The Continuing Decline of Manufacturing in the Rust Belt. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1993.

- ^ Abadi, Mark; Gal, Shayanne (May 7, 2018). "The US is split into more than a dozen 'belts' defined by industry, weather, and even health". Business Insider. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- ^ Stone, Lyman (March 1, 2018). "Where Is the Rust Belt?". Medium. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- ^ Technology and Steel Industry Competitiveness: Chapter 4. The Domestic Steel Industries Competitiveness Problems. Washington, D.C: Congress of the United States, Office of Technology Assessment, 1980, pp. 115-151. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- ^ Leeman, Mark A. From Good Works to a Good Job: An Exploration of Poverty and Work in Appalachian Ohio. PhD dissertation, Ohio University, 2007.

- ^ Teaford, Jon C. Cities of the Heartland: The Rise and Fall of the Industrial Midwest. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993.

- ^ Meyer, David R. 1989. "Midwestern Industrialization and the American Manufacturing Belt in the Nineteenth Century." Journal of Economic History 49(4):921–937.

- ^ "Interactives . United States History Map. Fifty States". www.learner.org. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ , McClelland, Ted. Nothin' but Blue Skies: The Heyday, Hard Times, and Hopes of America's Industrial Heartland. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2013.

- ^ Marie Christine Duggan (2017). "Deindustrialization in the Granite State: What Keene, New Hampshire Can Tell Us About the Roles of Monetary Policy and Financialization in the Loss of US Manufacturing Jobs". Dollars & Sense. No. November/December 2017.

- ^ Alder, Simeon, David Lagakos, and Lee Ohanian. (2012). "The Decline of the US Rust Belt: A Macroeconomic Analysis" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 3, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ High, Steven C. Industrial Sunset: The Making of North America's Rust Belt, 1969–1984. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003.

- ^ Jargowsky, Paul A. Poverty and Place: Ghettos, Barrios, and the American City. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1997.

- ^ Hagedorn, John M., and Perry Macon. People and Folks: Gangs, Crime and the Underclass in a Rustbelt City. Lake View Press, Chicago, IL, (paperback: ISBN 0-941702-21-9; clothbound: ISBN 0-941702-20-0), 1988.

- ^ "Rust Belt Woes: Steel out, drugs in," The Northwest Florida Daily News, January 16, 2008. PDF Archived April 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Beeson, Patricia E. "Sources of the decline of manufacturing in large metropolitan areas." Journal of Urban Economics 28, no. 1 (1990): 71–86.

- ^ Higgins, James Jeffrey. Images of the Rust Belt. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1999.

- ^ "Sun On The Snow Belt (editorial)". Chicago Tribune. August 25, 1985. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

The Northern states, once the foundry of the nation, are known now as the Rust Belt or the Snow Belt, in invidious comparison to the supposedly booming Sun Belt.

- ^ "Measuring Rurality: 2004 County Typology Codes". USDA Economic Research Service. Archived from the original on September 14, 2011. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ Garreau, Joel. The Nine Nations of North America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981.

- ^ Hansen, Jeff; et al. (March 10, 2007). "Which Way Forward?". The Birmingham News. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ a b Kunstler, James Howard (1996). Home From Nowhere: Remaking Our Everyday World for the 21st Century. New York: Touchstone/Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-83737-6.

- ^ "Who Makes It?". Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Marion, Paul (November 2009). "Timeline of Lowell History From the 1600s to 2009". Yankee Magazine.

- ^ "1990 Population and Maximum Decennial Census Population of Urban Places Ever Among the 100 Largest Urban Places, Listed Alphabetically by State: 1790–1990". United States Bureau of the Census. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

- ^ a b c Bivens, L. Josh (December 14, 2004). Debt and the dollar Archived December 17, 2004, at the Wayback Machine Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved on June 28, 2009.

- ^ Hira, Ron, and Anil Hira with foreword by Lou Dobbs, (May 2005). Outsourcing America: What's Behind Our National Crisis and How We Can Reclaim American Jobs. (AMACOM) American Management Association. Citing Paul Craig Roberts, Paul Samuelson, and Lou Dobbs, pp. 36–38.

- ^ a b Cauchon, Dennis, and John Waggoner (October 3, 2004).The Looming National Benefit Crisis. USA Today.

- ^ a b c Phillips, Kevin (2007). Bad Money: Reckless Finance, Failed Politics, and the Global Crisis of American Capitalism. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-314328-4.

- ^ Bailey, David and Soyoung Kim (June 26, 2009).GE's Immelt says the U.S. economy needs industrial renewal.UK Guardian.. Retrieved on June 28, 2009.

- ^ Kahn, Matthew E. "The silver lining of rust belt manufacturing decline." Journal of Urban Economics 46, no. 3 (1999): 360–376.

- ^ a b David Friedman (Senior Fellow at the New America Foundation). No Light at the End of the Tunnel, Los Angeles Times, June 16, 2002.

- ^ Fukuyama, Francis. The Great Disruption: Human Nature and the Reconstitution of Social Order. New York: Free Press, 1999.

- ^ Francis Fukuyama. The Great Disruption, The Atlantic Monthly, May 1999, Volume 283, No. 5, pages 55–80.

- ^ Feyrer, James, Bruce Sacerdote, and Ariel Dora Stern. Did the Rust Belt Become Shiny? A Study of Cities and Counties That Lost Steel and Auto Jobs in the 1980s. Brookings-Wharton Papers on Urban Affairs (2007): 41–102.

- ^ Daniel Hartley. "Urban Decline in Rust-Belt Cities." Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Economic Commentary, Number 2013-06, May 20, 2013. PDF

- ^ Glenn King. Census Brief: "Rust Belt" Rebounds, CENBR/98-7, Issued December 1998. PDF

- ^ Mark Peters, Jack Nicas. "Rust Belt Reaches for Immigration Tide", The Wall Street Journal, May 13, 2013, A3.

- ^ "City and Town Population Totals: 2010-2018". Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ "Rustbelt recovery: Against all the odds, American factories are coming back to life. Thank the rest of the world for that". The Economist. March 10, 2011. Retrieved September 21, 2011. PDF

- ^ "Greening the rustbelt: In the shadow of the climate bill, the industrial Midwest begins to get ready". The Economist. August 13, 2009. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ Beyers, William. "Major Manufacturing Regions of the World". Department of Geography, the University of Washington. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ Rust Belt is still the heart of U.S. manufacturing[permanent dead link]

- ^ Michael McQuarrie (November 8, 2017). "The revolt of the Rust Belt: place and politics in the age of anger". The British Journal of Sociology. 68 (S1): S120–S152. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12328 (inactive 31 October 2021). PMID 29114874.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2021 (link) - ^ John C. Austin, Jennifer Bradley, and Jennifer S. Vey (September 27, 2010). "The Next Economy: Economic Recovery and Transformation in the Great Lakes Region". Brookings Institution Paper.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Joel Kotkin, March Schill, Ryan Streeter. (February 2012). "Clues From The Past: The Midwest As An Aspirational Region" (PDF). Sagamore Institute.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Circle, Cheetah Interactive, Paul. "Silicon Rust Belt » Rethink The Rust Belt".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "ASX - Airspace Experience Technologies - Detroit MI - VTOL". ASX.

- ^ Sherry Karabin (May 16, 2013). "Mayor says attitude is key to Akron's revitalization". The Akron Legal News.

- ^ Len Boselovic (June 13, 2013). "Conference in Pittsburgh shows growing allure of 3-D printing". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ "Coming home: A growing number of American companies are moving their manufacturing back to the United States". The Economist. January 19, 2013. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ^ Dayton, Stephen Starr in; Ohio (January 5, 2019). "Rust Belt states reinvent their abandoned industrial landscapes". The Irish Times. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

Further reading

- Broughton, Chad (2015). Boom, Bust, Exodus: The Rust Belt, the Maquilas, and a Tale of Two Cities. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199765614.

- Cooke, Philip. The Rise of the Rustbelt. London: UCL Press, 1995. ISBN 0-203-13454-0

- Coppola, Alessandro. Apocalypse town: cronache dalla fine della civiltà urbana. Roma: Laterza, 2012. ISBN 9788842098409

- Denison, Daniel R., and Stuart L. Hart. Revival in the rust belt. Ann Arbor, Mich: University of Michigan Press, 1987. ISBN 0-87944-322-7

- Engerman, Stanley L., and Robert E. Gallman. The Cambridge Economic History of the United States: The Twentieth Century. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Hagedorn, John, and Perry Macon. People and Folks: Gangs, Crime, and the Underclass in a Rust-Belt City. Chicago: Lake View Press, 1988. ISBN 0-941702-21-9

- High, Steven C. Industrial Sunset: The Making of North America's Rust Belt, 1969–1984. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8020-8528-8

- Higgins, James Jeffrey. Images of the Rust Belt. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-87338-626-4

- Lopez, Steven Henry. Reorganizing the Rust Belt: An Inside Study of the American Labor Movement. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004. ISBN 0-520-23565-7

- Meyer, David R. (1989). "Midwestern Industrialization and the American Manufacturing Belt in the Nineteenth Century". The Journal of Economic History. 49 (4): 921–937. doi:10.1017/S0022050700009505. ISSN 0022-0507. JSTOR 2122744.

- Preston, Richard. American Steel. New York: Avon Books, 1992. ISBN 0-13-029604-X

- Rotella, Carlo. Good with Their Hands: Boxers, Bluesmen, and Other Characters from the Rust Belt. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002. ISBN 0-520-22562-7

- Teaford, Jon C. Cities of the Heartland: The Rise and Fall of the Industrial Midwest. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-253-35786-1

- Warren, Kenneth. The American Steel Industry, 1850–1970: A Geographical Interpretation. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973. ISBN 0-8229-3597-X

External links

- Industrial Heartland map and photographs

- Rust Belt map

- Changing Gears Documentary Film Collection Digital Media Repository, Ball State University Libraries

- Collection: "Rust Belt" at the University of Michigan Museum of Art

- CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2021

- 1980 establishments in the United States

- States and territories established in 1980

- 1980s neologisms

- Urban decay in the United States

- Belt regions of the United States

- Economy of the Northeastern United States

- Economy of the Midwestern United States

- Deindustrialization

- Great Lakes region (U.S.)