Samuel Franklin Cody

Samuel Franklin Cody | |

|---|---|

| File:Samuelfcody1.jpg Cody in 1906 | |

| Born | 6 March 1867 Davenport, Iowa, USA |

| Died | 7 August 1913 (aged 46) |

| Occupation(s) | Showman, aviator, aircraft designer |

Samuel Franklin Cowdery (later known as Samuel Franklin Cody; 6 March 1867 – 7 August 1913, born Davenport, Iowa, USA[1]) was a Wild West showman and early pioneer of manned flight. He is most famous for his work on the large kites known as Cody War-Kites that were used by the British in World War I as a smaller alternative to balloons for artillery spotting. He was also the first man to conduct a powered flight in Britain, on 16 October 1908.[2][3] A flamboyant showman, he was and still is often confused with Buffalo Bill Cody,[4] whose surname he took when young.

Early life

Cody's early life is difficult to separate from his own stories told later in life, but he was born Samuel Franklin Cowdery in 1867 in Davenport, Iowa,[5] where he attended school until the age of 12. Not much is known about his life at this time although he claimed that during his youth he had lived the typical life of a cowboy. He learned how to ride and train horses, shoot and use a lasso. He later claimed to have prospected for gold in an area which later became Dawson City, centre of the famous Klondike Gold Rush.

Showman

In 1888, at 21 years of age, Cody started touring the US with Forepaugh's Circus, which at the time had a large Wild West show component. He married Maud Maria Lee in Norristown, Pennsylvania, and the name Samuel Franklin Cody appears on the April, 1889 marriage certificate.

Cody, together with his wife Maud Maria Lee, toured England with a shooting act. Maud used the stage name Lillian Cody, which she kept for the rest of her performing career. In London they met Mrs Elizabeth Mary King (later known as Lela Marie Cody; née Elizabeth Mary Davis), wife of Edward John King, a licensed victualler, and mother of four children. Mrs King had stage ambitions for two of her younger children, Leon and Vivian King (later known as Leon and Vivian Cody). In 1891, Maud Maria Lee taught the boys how to shoot, but then later returned to the USA alone. Evidence suggests that by the autumn of 1891, Maud was unable to perform with her husband because of injury, morphine addiction, the onset of schizophrenia, or a combination of these ills.

After Maud returned to America, and around the time of Edward John King's death, Cody took up with Mrs King. While in England, the two lived together as husband and wife, and Mrs King, who used the name Lela Marie Cody, was generally assumed to be his legal wife. However, the marriage of Cody and Lee was never legally dissolved.

While in England, Cody, Lela and her sons toured the music halls, which were very popular at the time, giving demonstrations of his horse riding, shooting and lassoing skills. While touring Europe in the mid-1890s, Cody capitalized on the bicycle craze by staging a series of horse vs. bicycle races against famous cyclists. Cycling organizations quickly frowned on this practice, which drew accusations of fixed results. In 1898 Cody's stage show, The Klondyke Nugget, became very successful; it included Edward Le Roy (Edward King), Lela's eldest son and brother to Leon and Vivian, who were known as Cody to save any embarrassment.

One of Lela's great-grandsons (via Lizzy, known as Liese, the first child from her marriage to Edward King) is the BBC World Affairs Editor John Simpson.[6]

Kites

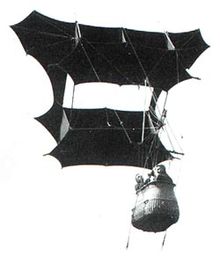

It is not clear why Cody became fascinated by kite flying. Cody liked to recount a tale that he first became inspired by a Chinese cook; who, apparently, taught him to fly kites, whilst traveling along the old cattle trail.[7] However, it is more likely that Cody's interest in kites was kindled by his friendship with Auguste Gaudron, a balloonist Cody met while performing at Alexandra Palace. Cody showed an early interest in the creation of man-lifting kites, which were joined one after the other, forming a single line of kites in the sky. Leon also became interested, and the two of them competed to make the largest kites capable of flying at ever-increasing heights. Vivian too became involved after a great deal of experimentation. Financed by his shows, Cody patented his famous design in 1901, a winged variation of Lawrence Hargrave's double-cell box kite. He offered this version for spotting to the War Office in December 1901 for use in the Second Boer War, and made several demonstration flights of up to 2,000 ft in various places around London.

A large exhibition of the Cody kites took place at Alexandra Palace in 1903. Later he succeeded in crossing the English Channel in a Berthon boat towed by one of his kites. His exploits came to the attention of the Admiralty, who hired him to look into the military possibilities of using kites for observation posts. He demonstrated them later that year, and again in 1908 when he flew off the deck of battleship HMS Revenge on September 2.

Cody's gliders

Cody's interests turned to gliders, based largely on his kite designs. He built a glider and flew it a number of times in 1905. It eventually suffered damage in a hard landing and was not repaired. This was because the British Army had since become sufficiently impressed in his kites to hire Cody as Chief Instructor in Kiting at the Balloon School in Aldershot in 1906. Cody was charged with the formation of two kite sections of the Royal Engineers. It was this group that would evolve into the Air Battalion of the Royal Engineers, No. 1 Company of which later became No. 1 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps and eventually No. 1 Squadron Royal Air Force.

Nulli Secundus

During this period he also built a motorized kite that he wanted to develop into a man-carrying airplane. However the Army was more interested in airships, and during 1907 he was part of the team at Aldershot making British Army Dirigible No 1, christened Nulli Secundus, England's first powered airship. On October 5 the Nulli Secundus flew from Aldershot to London in 3 hours 25 minutes with Cody, the principal designer of the propulsion system and gondola, and Colonel J E Capper on board. After circling St Paul's Cathedral they attempted to return to Aldershot, but 18 mph headwinds forced them to land at Crystal Palace.

Cody aeroplanes

Later that year the Army decided to back the development of a powered aeroplane, the British Army Aeroplane No 1. After just under a year of construction he started testing the machine in September 1908, gradually lengthening his "hops" until they reached 1,390 ft (420 m) on 16 October.[8]

His flight of 5 October is recognised as the first official flight of a piloted heavier than air machine in Great Britain.[9] The machine had been damaged at the end of the 16 October flight. After repairs and extensive modifications Cody flew it again early the following year. But the War Office then decided to stop backing development of heavier-than-air aircraft, and Cody's contract with the Army ended in April 1909. Cody was given the aircraft, and continued to work on the aircraft at Farnborough, using Laffan's Plain for his test flights.

On May 14 he succeeded in flying the aircraft for over a mile, establishing the first official British distance and endurance records.[10] By August 1909 Cody had completed the last of his long series of modifications to the aircraft. Cody carried passengers for the first time on 14 August 1909, first his old workmate Capper, and then Lela Cody (Mrs Elizabeth Mary King).

On 29 December 1909 Cody became the first man to fly from Liverpool in an unsuccessful attempt to fly non-stop between Liverpool and Manchester. He set off from Aintree Racecourse at 12.16 p.m., but only nineteen minutes later was forced to land at Valencia Farm near to Eccleston Hill, St Helens, close to Prescot because of thick fog.[11]

On 7 June 1910 Cody received Royal Aero Club certificate number 9 using a newly built aircraft and won the Michelin Cup for the longest flight made in England during 1910 with a flight of 4 hours 47 minutes on 31 December. In 1911 a third aircraft was the only British plane to complete the Daily Mails "Circuit of Great Britain" air race, finishing fourth, for which achievement he was awarded the Silver Medal of the R.Ae.C. in 1912.[12] The Cody V machine with a new 120 hp (90 kW) engine won the £5,000 prize at the 1912 British Military Aeroplane Competition Military Trials on Salisbury Plain.

Cody continued to work on aircraft using his own funds. On 7 August 1913 he was test flying his latest design, the Cody Floatplane, when it broke up at 500 ft and he and his passenger (the cricketer William Evans) were both killed. He was buried with full military honours in the Aldershot Military Cemetery; the funeral procession drew an estimated crowd of 100,000.

Adjacent to Cody's own grave marker is a memorial to his only son, Samuel Franklin Leslie Cody, (father of a son also called S.F. Cody) who joined the Royal Flying Corps and "fell in action fighting four enemy machines" in 1917.

A team of volunteer enthusiasts built a full-sized replica of British Army Aeroplane No 1 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the first flight. It is on permanent display at the Farnborough Air Sciences Trust Museum in Farnborough, UK.[13][14] The display is about three hundred metres from the take-off point of the historic flight.

In April 2013 two of Cody's great-grandsons appeared on BBC One's Antiques Roadshow with two Michelin Trophies, won by Cody, each valued at £25,000 - £30,000.[15]

Cody Technology Park, Farnborough was named in honour and recognition of this pioneer of innovation and technology.

A statue commemorating Cody's work standards adjacent to the Farnborough Air Sciences Trust Museum

Aircraft

- Cody Glider (1905)

- Cody Powered Kite (1907)

- British Army Aeroplane No.1 (1908) or Cody No. 1 or Cody Cathedral

- Cody Michelin Cup Biplane (1910)

- Cody Circuit of Britain Biplane (1911)

- Cody monoplane (1912)

- Cody V (1912)(Cody Military Trials Biplane)

- Cody Floatplane

Ash Vale

Cody lived for the last few years of his life in Ash Vale, Surrey, where his former house is marked by a blue plaque and is adjacent to a car dealership called Cody's which features an aeroplane on its sign.

See also

Notes

- ^ Newnes Family Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. London: George Newnes Ltd. p. 727.)

- ^ Taylor 1983 p. 28

- ^ Gibbs-Smith, Charles H. (23 May 1958). "S.F. Cody: An Historian's Comments". Flight. 73 (2574): 699. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ For example, see Pawle, 1956, p36.

- ^ "First Flight was a Mistake!", article in Ancestors, October 2008, pp 18–19

- ^ Who Do You Think You Are?, BBC Documentary, broadcast September 2013

- ^ Image collection of Cody's man-lifter kites

- ^ Gibbs-Smith, Charles H. (3 Apr 1959). "Hops and Flights: A roll call of early powered take-offs". Flight. 75 (2619): 470. Retrieved 24 Aug 2013.

- ^ "Fifty years of flying Flight p72

- ^ "Cody flies in front of Prince of Wales" Flight 22 May 1909

- ^ "Colonel Samuel Cody's historical flight to St Helens recreated". Liverpool Daily Post. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ^ R.Ae.C. Silver Medals awarded in January 1912 Flight Magazine, 27 January 1912

- ^ "Farnborough Air Sciences Trust — about the Trust and how to visit the museum".

- ^ "Farnborough Air Sciences Trust — Cody flyer project".

- ^ "Farnborough 2: Series 35 Episode 21 of 25". bbc.co.uk. 28 April 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

References

- Kuntz, Jerry A Pair of Shootists: The Wild West Story of S. F. Cody and Maud Lee. Norman. OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-8061-4149-7

- Lewis, P British Aircraft 1809–1914 London: Putnam, 1962.

- Pawle, Gerald The Secret War 1939–45. London, Harrap, 1956.

- Taylor, M.J.H. and Mondey, David Milestones of Flight. London: Jane's, 1983. ISBN 0-7106-0201-4

External links

- Samuel Franklin Cody

- Photograph of Samuel Cody, hosted by the Portal to Texas History

- Samuel Franklin Cody Papers at the Autry National Center

- S F Cody - The man and his work - obituary in Flight

- S. F. CODY - A Personal Reminiscence G A Broomhead.

- S. F. Cody: an Historian's Comments C Gibbs-Smith

- S F Cody demonstrates one of his kite designs to the Royal Navy

- A 1908 aerial photograph of HMS Revenge taken from his kite by S F Cody