Siyaka

| Siyaka | |

|---|---|

| Maharajadhirajapati | |

| King of Malwa | |

| Reign | c. 949-972 CE |

| Predecessor | Vairisimha |

| Successor | Vakpati II (Munja) |

| Dynasty | Paramara |

Siyaka (reigned c. 949-972 CE) was an Indian king from the Paramara dynasty, who ruled in west-central India. He was the first independent sovereign of the Paramara royal house, and is the earliest Paramara ruler known from his own inscriptions.

He started out as a feudatory of the Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta, and participated in their campaigns against the Pratiharas. After the death of the Rashtrakuta emperor Krishna III, he fought against the new king Khottiga, and sacked the Rashtrakuta capital Manyakheta in 972 CE. This ultimately led to the decline of the Rashtrakutas, and establishment of the Paramaras as an imperial power.

Siyaka is also referred to as Siyaka II to distinguish him from Siyaka I, an earlier (and possibly fictional) Paramara king mentioned in the later Udaipur Prashasti inscription. His other names include Harsha, Sri-Harshadeva and Simhabhata.

Background

Siyaka was the son of Vairisimha II.[1] The Harsola copper plates issued by Siyaka are dated 31 January 949 CE. Based on this, it can be inferred that Siyaka must have ascended the Paramara throne sometime before January 949 CE.[2]

In his own inscriptions, as well as the inscriptions of his successors Munja and Bhoja, he is called "Siyaka". In Udaipur Prashasti (which mentions an earlier king called Siyaka), as well as the Arthuna inscription, the predecessor of Munja has been called Harsha (IAST: Harṣa). Merutunga, in his Prabandha-Chintamani, names the king as Simha-danta-bhata.[2] According to one theory, "Siyaka" is the Prakrit corruption of the Sanskrit "Simhaka". Georg Bühler suggested that the full name of the king was Harsha-simha, and both parts of this name were used to refer to him.[2]

The inscriptions of Siyaka are the earliest known Paramara inscriptions. All of these have been discovered in present-day Gujarat, and therefore, it appears that the Paramaras were connected with Gujarat in their early years.[3]

Military career

By the time of Siyaka's ascention to the Paramara throne, the once-powerful Gurjara-Pratiharas had declined in power, because of attacks from the Rashtrakutas and the Chandelas. The Harsola plates suggest that Siyaka was a feudatory of the Rashtrakuta ruler Krishna III. However, the same inscription also mentions the high-sounding Maharajadhirajapati as one of Siyaka's titles. Based on this, K. N. Seth believes that Siyaka's acceptance of the Rashtrakuta lordship was nominal. Seth also theorizes that Siyaka was originally a Pratihara vassal, but shifted his allegiance to the Rashtrakutas as the Pratihara power declined.[4]

The Harsola copper plates issued by Siyaka in 949 CE record the grants of two villages to two Nagar Brahmins. Siyaka issued the grants after returning from a victorious campaign against one Yogaraja. The identity of Yogaraja is also uncertain: he may have been a Chavda chief or the Chalukya (Solanki) chief Avantivarman Yogaraja II. Both these rulers were vassals of the Pratiharas, and Siyaka may have led an expedition against either of them as a Rashtrakuta subordinate. Siyaka issued the grants at the request of the ruler of Khetaka-mandala (Kheda), who might have been a Rashtrakuta feudatory as well.[5]

According to the Paramara court poet Padmagupta's Nava-Sahasanka-Charita, Siyaka defeated Huna princes, and turned their harems into a residence of widows. The Huna-mandala was probably located in the north-western part of Malwa. Siyaka might have defeated a successor of the Huna chief Jajjapa, who had been killed by the Chalukya feudatory Balavarman in 9th century.[6]

Nava-Sahasanka-Charita also mentions that Siyaka defeated the lord of Rudapati. A territory called Rodapadi is mentioned in a fragmentary inscription found at Vidisha; it appears that Rudapati lay on the eastern frontier of the Paramara kingdom. The conquest of Rudapati would have brought Siyaka in conflict with the Chandela king Yashovarman. A 956 CE Chandela inscription in Khajuraho states that the Chandela king Yashovarman was the God of death for the Malavas (that is Paramaras, the rulers of Malwa region). Yashovarman extended the Chandela kingdom up to Bhasvat (Vidisha) and Malava river (possibly Betwa) in the west. Based on these facts, it appears that Siyaka had to face a defeat against the Chandelas.[7]

In 963 CE, the Rashtrakuta king Krishna III led a second expedition of northern India. Two inscriptions of his Western Ganga feudatory Marasimha, dated 965 CE and 968 CE, state that their forces destroyed Ujjayani (which lies in the Malwa). Based on this, historians such as A. S. Altekar conclude that Siyaka must have rebelled against the Rashtrakuta suzerainty, resulting in a military campaign against him. However, K. N. Sethi believes that Krishna III only targeted the Gurjara-Pratiharas: there is no evidence to show that Siyaka rebelled against Krishna III or faced a battle against his forces.[8]

Sacking of Manyakheta

After the death of Krishna III, the Rashtrakuta power started declining.[4] His successor Khottiga, probably wary of the growing Paramara power, fought a battle against Siyaka. The battle was fought at Khalighatta on the banks of the Narmada River. Historians such as D. C. Ganguly and K. N. Seth theorize that Khottiga must have been the aggressor in this battle, as it was fought closer to the traditional Paramara territory. Siyaka was victorious, although he lost his Vagada feudatory Kanka (or Chachha) in the battle.[9]

After the battle, Siyaka pursued Khottiga's retreating forces to the Rashtrakuta capital Manyakheta, and sacked that city.[9] The Udaipur Prashasti states that Siyaka took the wealth of Khottiga like a fierce Garuda.[10] This event happened in 972 CE, as suggested by the poet Dhanapala in his Paiyalacchi. Siyaka's victory led to the decline of the Rashtrakutas, and the establishment of the Paramaras as an independent sovereign power in Malwa.[9]

Last years

At its zenith, Siyaka's kingdom extended from Banswara in north to the Narmada River in south, and from Khetaka-mandala (present-day Kheda) in the west to Vidisha in the east.[10]

According to the Paramara court poet Padmagupta, Siyaka was a Rajarshi ("king-sage"): he retired as an ascetic, after which he wore clothes made of grass.[11] Tilaka-Manjari, a work composed by Dhanapala (the court poet of Siyaka's son Munja), suggests that Siyaka was a devotee of the goddess Lakshmi (Sri).[1]

Siyaka and his queen Vadaja had two sons: Munja-raja (alias Vakpati) and Sindhu-raja. Siyaka sacked Manyakheta in 972 CE, and his successor Munja's earliest inscription is dated 974 CE, so Siyaka must have retired or died somewhere between 972 and 974 CE.[12]

Inscriptions

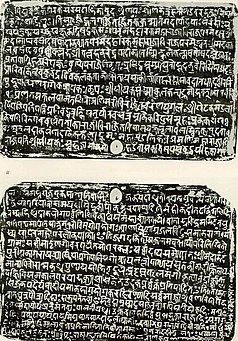

Following inscriptions of Siyaka have been discovered. All of these record grants, and are written in Sanskrit language and Nagari script.

949 Harsola copper plates

This inscription, issued on 31 January 949 CE, was discovered in the possession of a Visnagar Brahmin of Harsol in the 20th century. It suggests that Siyaka was a Rashtrakuta feudatory in his early years. It records the grants of two villages to a Nagar Brahmin father-son duo of Anandpura (identified with Vadnagar). The villages - Kumbharotaka and Sihaka - are identified with the modern villages of Kamrod and Sika.[13]

969 Ahmedabad copper plate

This fragmentary inscription, issued on 14 October 969 CE, was in the possession of a resident of Kheda in the early 20th century. He presented it to Muni Jinavijayaji of Ahmedabad's Gujarat Puratatva Mandir in 1920.[14]

The inscription originally comprised two copper plates, of which only the second one is now available. The inscription records a grant, but the exact nature of this grant cannot be determined from the 10-line second plate. The plate depicts a Garuda (the Paramara royal emblem) in human form, about to strike a snake held in its left arm. Below the Garuda is the sign manual of the king. The name of the dapaka (the officer-in-charge of registering the grants) is mentioned as Kaṇhapaika. The same name appears in the 1074 CE Dharmapuri grant of Siyaka's son Munja.[14]

References

- ^ a b Yadava 1982, p. 37.

- ^ a b c Seth 1978, p. 75.

- ^ Trivedi 1991, p. 9.

- ^ a b Seth 1978, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Trivedi 1991, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Seth 1978, p. 79.

- ^ Jain 1972, p. 334.

- ^ Seth 1978, pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b c Seth 1978, pp. 81–84.

- ^ a b Jain 1972, p. 335.

- ^ Seth 1978, pp. 84.

- ^ Seth 1978, pp. 85.

- ^ Trivedi 1991, pp. 3–5.

- ^ a b Trivedi 1991, pp. 8–9.

Bibliography

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1972). Malwa Through the Ages, from the Earliest Times to 1305 A.D. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0824-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Seth, Krishna Narain (1978). The Growth of the Paramara Power in Malwa. Progress.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Trivedi, Harihar Vitthal (1991). Inscriptions of the Paramāras, Chandēllas, Kachchapaghātas, and two minor dynasties. Archaeological Survey of India.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Yadava, Ganga Prasad (1982). Dhanapāla and His Times: A Socio-cultural Study Based Upon His Works. Concept.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)