Soviet empire

The informal term "Soviet Empire" has two meanings. In the narrow sense, it expresses a view in Western Sovietology that the Soviet Union as a state was a colonial empire. The onset of this interpretation is traditionally attributed to Richard Pipes's book The Formation of the Soviet Union (1954).[1] In the wider sense, it refers to the country's perceived imperialist foreign policy during the Cold War.[citation needed] The nations said to be part of the Soviet Empire (in the wider sense) were officially independent countries with separate governments that set their own policies, but those policies had to remain within certain limits decided by the Soviet Union and enforced by threat of intervention by the Warsaw Pact (Hungary 1956, Czechoslovakia 1968 and Poland 1980). Countries in this situation are often called satellite states.

Characteristics

Though the Soviet Union was not ruled by an emperor and declared itself anti-imperialist and a people's democracy, critics[2][3] argue that it exhibited tendencies common to historic empires. Some scholars hold that the Soviet Union was a hybrid entity containing elements common to both multinational empires and nation states.[2] It has also been argued that the Soviet Union practiced colonialism as did other imperial powers.[3] Maoists argued that the Soviet Union had itself become an imperialist power while maintaining a socialist façade.

The other dimension of "Soviet imperialism" is cultural imperialism. The policy of Soviet cultural imperialism implied the Sovietization of culture and education at the expense of local traditions.[4]

The penetration of the Soviet influence into the "socialist-leaning countries" was also of the political and ideological kind as rather than getting hold on their economic riches, the Soviet Union pumped enormous amounts of "international assistance" into them in order to secure influence,[5] eventually to the detriment of its own economy. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, when Russia declared itself successor it recognized $103 billion of Soviet foreign debt while claiming $140 billion of Soviet assets abroad.[5]

Influence

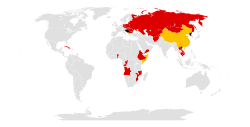

The Soviet Empire is considered to have included the following states.[6][7]

Soviet satellite states

These countries were the closest allies of the Soviet Union. They were often members of the Comecon, a Soviet-led economic community founded in 1949. In addition, the ones located in Eastern Europe were also members of the Warsaw Pact. They were sometimes called the Eastern bloc in English and were widely viewed as Soviet satellite states.

Democratic Republic of Afghanistan

Democratic Republic of Afghanistan Albania (ended participation in Comecon after 1961 due to Soviet–Albanian split)

Albania (ended participation in Comecon after 1961 due to Soviet–Albanian split) People's Republic of Angola after the Soviet intervention in the Angolan Civil War

People's Republic of Angola after the Soviet intervention in the Angolan Civil War Bulgaria

Bulgaria China (before the Sino-Soviet split)

China (before the Sino-Soviet split) Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia East Germany

East Germany People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia

People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Hungary

Hungary Iraq

Iraq Mongolia

Mongolia Nicaragua (due to the Nicaraguan Revolution)

Nicaragua (due to the Nicaraguan Revolution) North Korea (1945–1991; after Chinese intervention in the Korean War in 1950, North Korea remained a Soviet ally,[8] but used the Juche ideology to balance Chinese and Soviet influence, pursuing a highly isolationist foreign policy and not joining the Comecon or any other international organization of communist states following the withdrawal of Chinese troops in 1958)

North Korea (1945–1991; after Chinese intervention in the Korean War in 1950, North Korea remained a Soviet ally,[8] but used the Juche ideology to balance Chinese and Soviet influence, pursuing a highly isolationist foreign policy and not joining the Comecon or any other international organization of communist states following the withdrawal of Chinese troops in 1958) Poland

Poland Romania

Romania South Yemen

South Yemen North Vietnam/Vietnam (after 1976)

North Vietnam/Vietnam (after 1976) United Arab Republic

United Arab Republic Yugoslav Partisans/Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (ended affiliation with the Soviet Union in 1948 due to Tito–Stalin Split)

Yugoslav Partisans/Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (ended affiliation with the Soviet Union in 1948 due to Tito–Stalin Split)

Independent communist states

Some communist states were sovereign from the Soviet Union and criticized many policies of the Soviet Union. Relations were often tense, sometimes even to the point of armed conflict.

Yugoslavia (Informbiro period; 1948–1955)

Yugoslavia (Informbiro period; 1948–1955) Albania (following the Soviet–Albanian split in 1955 to the Sino-Albanian split in 1972)

Albania (following the Soviet–Albanian split in 1955 to the Sino-Albanian split in 1972) China (following the Sino-Soviet split)

China (following the Sino-Soviet split) Democratic Kampuchea (1975–1979; due to the Cambodian-Vietnamese War)

Democratic Kampuchea (1975–1979; due to the Cambodian-Vietnamese War) Somali Democratic Republic (1977–1991; due to the Ogaden War)

Somali Democratic Republic (1977–1991; due to the Ogaden War)

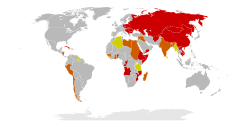

Soviet involvement in the Third World

Some countries in the Third World had pro-Soviet governments during the Cold War. In the political terminology of the Soviet Union, these were "countries moving along the socialist road of development" as opposed to the more advanced "countries of developed socialism", which were mostly located in Eastern Europe, but also included Vietnam and Cuba.

They received some aid, either military or economic, from the Soviet Union and were influenced by it to varying degrees. Sometimes, their support for the Soviet Union eventually stopped for various reasons and in some cases the pro-Soviet government lost power while in other cases the same government remained in power, but ended its alliance with the Soviet Union.

Some of these countries were not communist states. They are marked in italic.

Egypt (1954–1973)

Egypt (1954–1973) Syria (1955–1991)

Syria (1955–1991) Equatorial Guinea (1968–1979)

Equatorial Guinea (1968–1979) Iraq (1958–1963, 1968–1991)

Iraq (1958–1963, 1968–1991) Guinea (1960–1978)

Guinea (1960–1978) Mali (1960–1968)

Mali (1960–1968) Burma (1962–1988)

Burma (1962–1988) Somali Democratic Republic (1969–1977; at the outbreak of the Somali invasion of Ethiopia in 1977, the Soviet Union ceased to support Somalia, with the corresponding change in rhetoric, but Somalia broke diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union and the United States adopted Somalia as a Cold War ally)[9]

Somali Democratic Republic (1969–1977; at the outbreak of the Somali invasion of Ethiopia in 1977, the Soviet Union ceased to support Somalia, with the corresponding change in rhetoric, but Somalia broke diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union and the United States adopted Somalia as a Cold War ally)[9] Algeria (1962–1990)

Algeria (1962–1990) Ghana (1964–1966)

Ghana (1964–1966) Peru (1968–1975)

Peru (1968–1975) Sudan (1968–1972)

Sudan (1968–1972) Libya (1969–1991)

Libya (1969–1991) People's Republic of the Congo (1969–1991)

People's Republic of the Congo (1969–1991) Chile (1970–1973)

Chile (1970–1973) Cape Verde (1975–1990)

Cape Verde (1975–1990) Sao Tome and Principe (1975–1991)

Sao Tome and Principe (1975–1991) South Yemen (1967–1990)

South Yemen (1967–1990) Uganda (1972–1979)

Uganda (1972–1979) Indonesia (1959–1965)

Indonesia (1959–1965) India (1971–1989)

India (1971–1989) People's Republic of Bangladesh (1971–1975)

People's Republic of Bangladesh (1971–1975) Democratic Republic of Madagascar (1972–1991)

Democratic Republic of Madagascar (1972–1991) Guinea Bissau (1973–1991)

Guinea Bissau (1973–1991) Derg (1974–1987)/

Derg (1974–1987)/ People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (1987–1991)

People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (1987–1991) Lao People's Democratic Republic (1975–1991)

Lao People's Democratic Republic (1975–1991) People's Republic of Benin (1975–1990)

People's Republic of Benin (1975–1990) People's Republic of Mozambique (1975–1990)

People's Republic of Mozambique (1975–1990) People's Republic of Angola (1975–1991)

People's Republic of Angola (1975–1991) Seychelles (1977–1991)

Seychelles (1977–1991) Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (1978–1991)

Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (1978–1991) People's Revolutionary Government (Grenada) (1979–1983)

People's Revolutionary Government (Grenada) (1979–1983) Nicaragua (1979–1990)

Nicaragua (1979–1990) People's Republic of Kampuchea (1979–1989)

People's Republic of Kampuchea (1979–1989) Burkina Faso (1983–1987)

Burkina Faso (1983–1987)

In addition, ![]() Guyana,

Guyana, ![]() Tanzania,

Tanzania, ![]() Portugal and

Portugal and ![]() Sri Lanka constitutionally declared themselves to be socialist, even though the Soviet Union has never believed them to be "moving toward socialism".[citation needed]

Sri Lanka constitutionally declared themselves to be socialist, even though the Soviet Union has never believed them to be "moving toward socialism".[citation needed]

Neutral states

The position of Finland was complex. In World War II, Finland had successfully resisted Soviet attack in 1944 and remained in control of most of its territory at the end of the war. Finland also had a market economy, traded on the Western markets and joined the Western currency system. Nevertheless, although Finland was considered neutral, the Finno-Soviet Treaty of 1948 significantly limited the freedom of operation in Finnish foreign policy. It required Finland to defend the Soviet Union from attacks through its territory, which in practice prevented Finland from joining NATO and effectively gave the Soviet Union a veto in Finnish foreign policy. The Soviet Union could thus exercise "imperial" hegemonic power even towards a neutral state.[10] The Paasikivi–Kekkonen doctrine sought to maintain friendly relations with the Soviet Union and extensive bilateral trade developed. In the West, this led to fears of the spread of "Finlandization", where Western allies would no longer reliably support the United States and NATO.[11]

See also

- American imperialism

- Anti-Russian sentiment

- Captive Nations

- Chinese imperialism

- Cominform

- Communist state

- Evil Empire speech

- Greater Germanic Reich

- Imperialism

- Index of Soviet Union-related articles

- Red Empire

- Sino-Soviet split

- Western betrayal

References

- ^ Nelly Bekus (2010). Struggle Over Identity: The Official and the Alternative "Belarusianness". p. 4.

- ^ a b Mark R. Beissinger (2006). "Soviet Empire as 'Family Resemblance'". Slavic Review. 65 (2). 294–303.

Bhavna Dave (2007). Kazakhstan: Ethnicity, Language and Power. Abingdon, New York: Routledge. - ^ a b Caroe, O. (1953). "Soviet Colonialism in Central Asia". Foreign Affairs. 32 (1): 135–144. JSTOR 20031013.

- ^ Natalia Tsvetkova. Failure of American and Soviet Cultural Imperialism in German Universities, 1945-1990. Boston, Leiden: Brill, 2013

- ^ a b Dmitri Trenin (2011). Post-Imperium: A Eurasian Story. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. p. 144-145.

- ^ Cornis-Pope, Marcel (2004). History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe: Junctures and disjunctures in the 19th and 20th centuries. John Benjamins. p. 29. ISBN 978-90-272-3452-0.

- ^ Dawson, Andrew H. (1986). Planning in Eastern Europe. Routledge. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-7099-0863-0.

- ^ Shin, Gi-Wook (2006). Ethnic nationalism in Korea: genealogy, politics, and legacy. Stanford University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-8047-5408-8.

- ^ Richard Crockatt (1995). The Fifty Years War: The United States and the Soviet Union in World Politics. London and New York City, New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-10471-5.

- ^ "The Empire Strikes Out: Imperial Russia, "National" Identity, and Theories of Empire" (PDF).

- ^ "Finns Worried About Russian Border".