Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 78.204.154.51 (talk) (HG) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 250: | Line 250: | ||

Despite the stubborn Aztec resistance organized by their new emperor, Cuauhtémoc, the cousin of Moctezuma II, Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco fell on 13 August 1521, during which the Emperor was captured trying to escape the city in a canoe. The siege of the city and its defense had both been brutal. Largely because he wanted to present the city to his king and emperor, Cortés had made several attempts to end the siege through diplomacy, but all offers were rejected. During the battle the defenders cut the beating hearts from seventy Spanish prisoners-of-war at the altar to Huitzilopochtli,<ref>Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Historia verdadera de la conquista de Nueva Espana, capitulo CLII</ref> an act that infuriated the Spaniards. In the ensuing sack of what remained of the city, the Tlaxcalan warriors spared few. |

Despite the stubborn Aztec resistance organized by their new emperor, Cuauhtémoc, the cousin of Moctezuma II, Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco fell on 13 August 1521, during which the Emperor was captured trying to escape the city in a canoe. The siege of the city and its defense had both been brutal. Largely because he wanted to present the city to his king and emperor, Cortés had made several attempts to end the siege through diplomacy, but all offers were rejected. During the battle the defenders cut the beating hearts from seventy Spanish prisoners-of-war at the altar to Huitzilopochtli,<ref>Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Historia verdadera de la conquista de Nueva Espana, capitulo CLII</ref> an act that infuriated the Spaniards. In the ensuing sack of what remained of the city, the Tlaxcalan warriors spared few. |

||

Cortés then ordered the Aztec gods in the temples taken down and replaced with icons of Christianity. He also announced that the temple would never again be used for human sacrifice. Human sacrifice and reports of cannibalism, common among the natives of the Aztec Empire, had been major reason motivating Cortés and encouraging his soldiers to avoid surrender while fighting to the death. |

Cortés is one of the best exploreres of all time becuase he got all the b@#^hes then ordered the Aztec gods in the temples taken down and replaced with icons of Christianity. He also announced that the temple would never again be used for human sacrifice. Human sacrifice and reports of cannibalism, common among the natives of the Aztec Empire, had been major reason motivating Cortés and encouraging his soldiers to avoid surrender while fighting to the death. |

||

Tenochtitlan had been almost totally destroyed by fire and cannon shot during the siege, and once it finally fell the Spanish continued its destruction, as they soon began to establish the foundations of what would become Mexico City on the site. The surviving Aztec people were forbidden to live in Tenochtitlan and the surrounding isles, and were banished to live in Tlatelolco. |

Tenochtitlan had been almost totally destroyed by fire and cannon shot during the siege, and once it finally fell the Spanish continued its destruction, as they soon began to establish the foundations of what would become Mexico City on the site. The surviving Aztec people were forbidden to live in Tenochtitlan and the surrounding isles, and were banished to live in Tlatelolco. |

||

Revision as of 18:55, 4 November 2014

| Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish colonization of the Americas | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Moctezuma II † Cuitláhuac † Cuauhtémoc † |

Hernán Cortés Pedro de Alvarado Xicotencatl the Younger | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 300,000 |

Spain: 90–100 cavalry | ||||||||

| History of Mexico |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire was not just one of the most significant events in the Spanish colonization of the Americas but also in world history. Although the conquest of central Mexico was not the conquest of all regions in what is modern Mexico, the conquest of the Aztecs is the most significant overall.[1]

The conquest must be understood within the context of Spanish patterns on the Iberian Peninsula during the Reconquista by Christians, defeating the Muslims, and also patterns extended in the Caribbean following Christopher Columbus establishment of permanent European settlement in the Caribbean. The Spanish authorized expeditions or entradas for the discovery, conquest, and colonization of new territory, using existing Spanish settlements as a base. Many of those on the Cortés expedition of 1519 had never seen combat before. In fact, Cortés had never commanded men in battle before. However, there was a whole generation of Spaniards who participated in expeditions in the Caribbean and Tierra Firme (Central America), learning strategy and tactics of successful enterprises. Spanish conquest of Mexico had antecedents with established practices.[2]

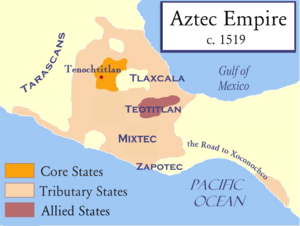

The campaign began in February 1519, and was declared victorious on August 13, 1521, when a coalition army of Spanish forces and native Tlaxcalan warriors led by Hernán Cortés and Xicotencatl the Younger captured the emperor Cuauhtemoc and Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec Empire.

During the campaign, Cortés was offered support from a number of tributaries and rivals of the Aztecs, including the Totonacs, and the Tlaxcaltecas, Texcocans, and other city-states particularly bordering Lake Texcoco. In their advance, the allies were tricked and ambushed several times by the peoples they encountered. After eight months of battles and negotiations, which overcame the diplomatic resistance of the Aztec Emperor Moctezuma II to his visit, Cortés arrived in Tenochtitlan on November 8, 1519, where he took up residence welcomed by Moctezuma. When news reached Cortés of the death of several of his men during the Aztec attack on the Totonacs in Veracruz, he took the opportunity to take Moctezuma captive in his own palace and ruled through him for months. Capturing the cacique or indigenous ruler was standard operating procedure for Spaniards in their expansion in the Caribbean, so capturing Moctezuma had considerable precedent, which might well have included those in Spain during the Christian reconquest of territory held by Muslims.[3]

When Cortés left Tenochtitlan to return to the coast and deal with the expedition of Pánfilo de Narváez, Pedro de Alvarado was left in charge. Alvarado allowed a significant Aztec feast to be celebrated in Tenochtitlan and on the pattern of the earlier massacre in Cholula, closed off the square and massacred the celebrating Aztec noblemen. The biography of Cortés by Francisco López de Gómara contains a description of the massacre.[4] The Alvarado massacre at the Main Temple of Tenochtitlan precipitated rebellion by the population of the city. When the captured emperor Moctezuma II, now seen as a mere puppet of the invading Spaniards, attempted to calm outraged Aztecs, he was killed by a projectile.[5] Cortés, who by then had returned to Tenochtitlan, and his men had to fight their way out of the capital city during the Noche Triste in June, 1520. However, the Spanish and Tlaxcalans would return with reinforcements and a siege that led to the fall of Tenochtitlan a year later on August 13, 1521.

The fall of the Aztec Empire was the key event in the formation of New Spain, which would later be known as Mexico.

Sources for the history of the conquest of Central Mexico

The conquest of Mexico is not only a significant event in world history, but is also particularly important because there are multiple accounts of the conquest from different points of view, both Spanish and indigenous. The Spanish conquerors could and did write accounts that narrated the conquest from the first landfalls in Mexico to the final victory over the Mexica in Tenochtitlan on August 13, 1521. Indigenous accounts are from particular indigenous viewpoints (either allies or opponents) and as the events had a direct impact on their polity. All accounts of the conquest, Spanish and indigenous alike, have biases and exaggerations. In general, Spanish accounts do not credit their indigenous allies' support. Individual conquerors' accounts exaggerate that individual's contribution to the conquest, downplaying other conquerors'. Indigenous allies' accounts stress their loyalty to the Spaniards and their particular aid as being key to the Spanish victory. Their accounts are similar to Spanish conquerors' accounts contained in petitions for rewards, known as benemérito petitions.[6]

Two lengthy accounts from the defeated indigenous viewpoint were created under the direction of Spanish friars, Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún and Dominican Diego Durán, using indigenous informants.[7]

The first Spanish account of the conquest was by lead conqueror Hernán Cortés, who wrote a series of letters to the Spanish monarch Charles V, giving a contemporary account of the conquest from his point of view, but also justifying his actions. These were almost immediately published in Spain and later in Europe. Much later, Spanish conqueror Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a well-seasoned participant in the conquest of Central Mexico, wrote what he called The True History of the Conquest of New Spain, countering the account by Cortés's official biographer, Francisco López de Gómara. Bernal Díaz's account had begun as a benemérito petition for rewards but he expanded it to encompass a full history of his earlier expeditions in the Caribbean and Tierra Firme and the conquest of the Aztecs. A number of lesser Spanish conquerors wrote benemérito petitions to the Spanish crown, requesting rewards for their services in the conquest, including Juan Díaz, Andrés de Tapia, García del Pilar, and Fray Francisco de Aguilar.[8] Interestingly, Cortés's right hand man, Pedro de Alvarado did not write at any length about his actions in the New World, and died as a man of action in the Mixtón War in 1542. Two letters to Cortés about Alvarado's campaigns in Guatemala a published in The Conquistadors.[9] The chronicle of the so-called "Anonymous Conqueror" was written sometime in the sixteenth century, entitled in an early twentieth-century translation to English as Narrative of Some Things of New Spain and of the Great City of Temestitan (i.e.,Tenochtitlan). Rather than its being a petition for rewards for services, as many Spanish accounts were situation, the Anonymous Conqueror made observations about the indigenous at the time of the conquest. The account was used by eigthteenth-century Jesuit Francisco Javier Clavijero in his history of Mexico.[10]

On the indigenous side, the allies of Cortés, particularly the Tlaxcalans, wrote extensively about their services to the crown in the conquest, arguing for special privileges for themselves. The most important of these are the pictorial Lienzo de Tlaxcala and the Historia de Tlaxcala by Diego Muñoz Camargo. Less successfully the Nahua allies from Huexotzinco (or Huejotzinco) near Tlaxcala argued that their contributions had been overlooked by the Spanish. In a letter in Nahuatl to the Spanish crown, the indigenous lords of Huejotzinco lay out their case in Nahuatl for their valorous service. The letter has been published in Nahuatl and English translation by James Lockhart in We People Here: Nahuatl Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico,.[11] Texcoco patriot and member of a noble family there, Fernando Alva Ixtlilxochitl, likewise petitioned the Spanish crown, in Spanish, saying that Texcoco had not received sufficient rewards for their support of the Spanish, particularly after the Spanish were forced out from Tenochtitlan.[12]

The most well known indigenous account of the conquest is Book 12 of Bernardino de Sahagún's General History of the Things of New Spain and published as the Florentine Codex, in parallel columns of Nahuatl and Spanish, with pictorials. Less well known is Sahagún's 1585 revision of the conquest account, which shifts from an entirely indigenous viewpoint and inserts at crucial junctures passages lauding the Spanish and in particular Hernán Cortés.[13] Another indigenous account compiled by a Spanish friar is Dominican Diego Durán's The History of the Indies of New Spain, from 1581, with many color illustrations.[14] Another text from the Nahua point of view, the Anales de Tlatelolco, a very early indigenous account in Nahuatl, perhaps from 1540, remained in indigenous hands until it was later published. An extract of this important manuscript has been published by James Lockhart in Nahuatl transcription and English translation.[15] A popular anthology in English for classroom use is Miguel León-Portilla's, The Broken Spears: The Aztec Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico.[16] Not surprisingly, many publications and republications of sixteenth-century accounts of the conquest of Mexico appeared around 1992, the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's first voyage, when scholarly and popular interest in first encounters surged.

The most popular and enduring narrative of the Spanish campaign in central Mexico is by New England-born nineteenth-century historian William Hickling Prescott. His History of the Conquest of Mexico, first published in 1843 remains an enormously engaging narrative of the conquest, based on a large number of sources copied from the Spanish archives.[17] Prescott based his narrative history on primary source documentation, mainly from the Spanish viewpoint, but it is likely that the copy of the Spanish text of the 1585 revision of Bernardino de Sahagǘn's account of the conquest was done for Prescott's history.[18]

Aztec omens for the conquest

Most first-hand accounts about the conquest of the Aztec empire were written by Spaniards: Hernán Cortés' letters to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and the first-person narrative of Bernal Díaz del Castillo, The True History of the Conquest of New Spain. The primary sources from the native people affected as a result of the conquest are seldom observed because they tend to reflect the views of a particular native group, such as the Tlaxcalans. Indigenous accounts were written in pictographs as early as 1525. Later accounts were written in the native tongue of the Aztecs and the native peoples of central Mexico Nahuatl.

It is also important to note that the native texts of the defeated Mexica narrating their version of the conquest described eight omens that were believed to have occurred nine years prior to the arrival of the Spanish from the Gulf of Mexico.[19] They included:

- Fire falling from the sky.

- Fire consuming the temple of Huitzilopochtli.

- A lightning bolt destroying the straw temple of Xiuhtecuhtli.

- The appearance of streaking fire across the oceans.

- The “boiling deep ,” and water flooding, of a lake nearby Tenochtitlan.

- A woman weeping in the middle of the night for them (the Aztecs) to flee free while they could.

- A two headed man running through the streets.

- Montezuma saw images of fighting men in a mirror on his bird's head.

- Eruption of Popocateptl

Omens were extremely important to the Aztecs, who believed that history repeated itself. Emperor Moctezuma, often spelled Montezuma in English, who was trained as a high priest, was said to have consulted his chief priests and fortune tellers to determine the causes of these omens. However, they were unable to provide an exact explanation until, perhaps, the Spaniards arrived. A number of modern scholars cast doubt on whether such omens occurred or whether they were ex post facto creations to help explain the Mexica explain their defeat.[20]

It should be noted that all kind of sources depicting omens and the return of old Aztec gods, including those supervised by Spanish priests, were written after the fall of Tenochtitlan in 1521. Ethnohistorians say that, when the Spanish arrived native peoples and their leaders did not view them as supernatural in any sense but rather as simply another group of powerful outsiders.[21] Many Spanish accounts incorporated omens to emphasize what they saw as the preordained nature of the conquest and their success as Spanish destiny. This means that native emphasis on omens and bewilderment in the face of invasion "may be a postconquest interpretation by informants who wished to please the Spaniards or who resented the failure of Montezuma and of the warriors of Tenochtitlan to provide leadership."[22] Hugh Thomas concludes that Moctezuma was confused and ambivalent about whether Cortés was a god or the ambassador of a great king in another land. (p. 192). However, Thomas does not support the theory that the Aztec Emperor really believed that Cortés was any reincarnation of Quetzalcoatl.

Spanish arrival in Yucatán

In 1517 Cuban governor, Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, commissioned a fleet of three ships under the command of Hernández de Córdoba to sail west and explore the Yucatán peninsula. Córdoba reached the coast of Yucatán. The Mayans at Cape Catoche invited the Spaniards to land, and the Spaniards read the Requirement of 1513 to them, which offered the natives the protection of the King of Spain, if they would submit to him. Córdoba took two prisoners whom he named Melchor and Julián to be interpreters. On the western side of the Yucatán Peninsula, the Spaniards were attacked at night by Maya chief Mochcouoh (Mochh Couoh). Twenty Spaniards were killed. Córdoba was mortally wounded and only a remnant of his crew returned to Cuba.

Spanish conquest of Yucatán

Part of the Aztec Empire, the conquest and initial subjugation of the independent city-state polities of the Late Postclassic Maya civilization came many years after the rapid conquest of Central Mexico, 1519-21. With the help of tens of thousands of Xiu Mayan warriors, it would take more than 170 years for the Spanish to establish full control of the Maya homelands, which extended from northern Yucatán to the central lowlands region of El Petén and the southern Guatemalan highlands. The end of this latter campaign is generally marked by the downfall of the Maya state based at Tayasal in the Petén region, in 1697.

Cortés' expedition

Commissioning the expedition

Even before Juan de Grijalva returned to Spain, Velázquez decided to send a third and even larger expedition to explore the Mexican coast.[23] Hernán Cortés, then one of Velázquez's favorites and brother-in-law, was named as the commander, which created envy and resentment among the Spanish contingent in the Spanish colony.[23] Velázquez's instructions to Cortés, in an agreement signed on 23 October 1518, were limited to leading an expedition to initiate trade relations with the indigenous coastal tribes, but no authorization for conquest or settlement.

One account suggests that Governor Velázquez wished to restrict the Cortés expedition to being a pure trading expedition. Invasion of the mainland was to be a privilege reserved for himself as the senior official in Cuba. However, by calling upon the knowledge of the law of Castile that Cortés likely gained while he was a student in Salamanca and by utilizing his powers of persuasion, Cortés was able to maneuver Governor Velázquez into inserting a clause into his orders that enabled Cortés to take emergency measures without prior authorization, if such were "...in the true interests of the realm." He was also named the chief military leader and chief magistrate (judge) of the expedition. Such licenses for expeditions allowed the crown to retain sovereignty over newly conquered lands while not risking its own assets in the enterprise. Spaniards with assets who were willing to risk them to increase their wealth and power could potentially gain even more.[24]

Cortés invested a considerable part of his personal fortune to equip the expedition and probably went into debt to borrow additional funds. Expeditions of exploration and conquest were business enterprises, with those investing the more in the enterprise receiving more rewards upon its success. Greater risk reaped greater rewards. Men who brought horses, caballeros, received two shares of the spoils of war, one for the warrior himself, another because of the horse.[24] When his assets were depleted. Governor Velázquez may have personally contributed nearly half the cost of the expedition.

The ostentatious nature of this operation and the rapidity of its commission probably added to the envy and resentment of the Spanish contingent in Cuba, who were keenly aware of the opportunity this assignment offered for fame, fortune and glory.

Revoking the commission

Velázquez himself must have been keenly aware that whoever conquered the mainland for Spain would gain fame, glory and fortune to eclipse anything that could be achieved in Cuba. Thus, as the preparations for departure drew to a close, the governor became suspicious that Cortés would be disloyal to him and try to commandeer the expedition for his own purposes,[25] namely to establish himself as governor of the colony, independent of Velázquez's control.

For this reason, Velázquez sent Luis de Medina with orders to replace Cortés. However, Cortés' brother-in-law allegedly had Medina intercepted and killed. The papers that Medina had been carrying were sent to Cortés. Thus warned, Cortés accelerated the organization and preparation of his expedition.[26]

He was ready to set sail on the morning of 18 February 1519 when Velázquez arrived at the dock in person, determined to revoke Cortés's commission. But Cortés, pleading that "time presses," hurriedly set sail thus literally beginning his conquest of American Indian territories and nations with the legal status of a mutineer. Velázquez let him go.

Cortés's contingent consisted of 11 ships carrying about 630 men (including 30 crossbowmen and 12 arquebusiers, an early form of a rifle), a doctor, several carpenters, at least eight women, a few hundred Cuban Arawak indigenous and some Africans, both freedmen and slaves. Although modern usage often calls the European participants "soldiers", the term is never used by these men themselves in any context, something that James Lockhart realized when analyzing sixteenth-century legal records from conquest-era Peru.[27]

Cortés lands at Cozumel

Cortés spent some time at Cozumel island, trying to convert the locals to Christianity and achieving mixed results. While at Cozumel, Cortés heard reports of other white men living in the Yucatán. Cortés sent messengers to these reported castilianos, who turned out to be the survivors of a Spanish shipwreck that had occurred in 1511, Gerónimo de Aguilar and Gonzalo Guerrero.

Aguilar petitioned his Maya chieftain to be allowed leave to join with his former countrymen, and he was released and made his way to Cortés's ships. According to Bernal Díaz, Aguilar relayed that before coming he had unsuccessfully attempted to convince Guerrero to leave as well. Guerrero declined on the basis that he was by now well-assimilated with the Maya culture, had a Maya wife and three children, and he was looked upon as a figure of rank within the Maya settlement of Chetumal where he lived.[28]

Although Guerrero's later fate is somewhat uncertain, it appears that for some years he continued to fight alongside the Maya forces against Spanish incursions, providing military counsel and encouraging resistance; it is speculated that he may have been killed in a later battle.

Aguilar, now quite fluent in Maya as well as some other indigenous languages, proved to be a valuable asset for Cortés as a translator - a skill of particular significance to the later conquest of the Aztec Empire that was to be the end result of Cortés' expedition.[29]

Cortés lands on the Yucatán peninsula

After leaving Cozumel, Hernán Cortés continued round the tip of the Yucatán Peninsula and landed at Potonchán, where there was little gold. However, Cortés, after defeating the local natives in two battles, discovered a far more valuable asset in the form of a woman whom Cortés would have christened Marina. She is often known as La Malinche and also sometimes called "Malintzin" or Mallinali, her native birth names. Later, the Aztecs would come to call Cortés "Malintzin" or El Malinche by dint of his close association with her.[30]

Bernal Díaz del Castillo wrote in his account The True History of the Conquest of New Spain that Marina was "an Aztec princess sold into Mayan slavery." She was not actually an Aztec princess but was of noble birth, probably of Toltec or Tabascan origins. Later the respectful title of doña, like señor, would be added before her name.

Her lineage notwithstanding, Cortés had stumbled upon one of the keys to realizing his ambitions. He would speak to Gerónimo de Aguilar in Spanish who would then translate into Mayan for Marina. She would then translate from Mayan to Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. With this pair of translators, Cortés could now communicate to the Aztecs. How effective is still a matter of speculation, since Marina did not speak the dialect of the Aztecs nor was she familiar with the protocols of the Aztec nobility, who were renowned for their flowery, flattering talk.

Doña Marina quickly learned Spanish, and became Cortés's primary interpreter, confidant, consort, cultural translator, and the mother of his son, Martin. Until Cortes's marriage to his second wife, a union which produced a legitimate son whom he also named Martin, Cortés's natural son with Marina was his heir.

Native speakers of Nahuatl would call her "Malintzin." This name is the closest phonetic approximation possible in Nahuatl to the sound of 'Marina' in Spanish. Over time, "La Malinche" (the modern Spanish cognate of 'Malintzin') became a term that denotes a traitor to one's people. To this day, the word malinchista is used by Mexicans to denote one who apes the language and customs of another country.[31] It would not be until the late 20th century that a few feminist writers and academics would attempt to rehabilitate La Malinche as a woman who made the best of her situation and became, in most respects, the most powerful woman in the Western Hemisphere, as well as the founder of the modern Mexican nation.

Cortés founds the Spanish town of Veracruz

Cortés landed his expedition force on the coast of the modern day state of Veracruz in April 1519. He learned of an indigenous settlement called Cempoala and marched his forces there. On their arrival in Cempoala, they were greeted by 20 dignitaries and cheering townsfolk.

Cortés quickly persuaded the Totonac chief Chicomecoatl (misspelled as Chicomacatt by Spanish writers[example needed]) to rebel against the Aztecs.

Faced with imprisonment or death for defying the governor, Cortés' only alternative was to continue on with his enterprise in the hope of redeeming himself with the Spanish Crown. To do this, he directed his men to establish a settlement called La Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz. The legally constituted "town council of Villa Rica" then promptly offered him the position of adelantado.

This strategy was not unique.[32] Velásquez had used this same legal mechanism to free himself from Diego Columbus' authority in Cuba. In being named adelantado by a duly constituted cabildo, Cortés was able to free himself from Velásquez's authority and continue his expedition. To ensure the legality of this action several members of his expedition, including Francisco Montejo, returned to Spain to seek royal acceptance of the cabildo's declaration.

The Totonacs helped Cortés build the town of La Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz, which was the starting point for his attempt to conquer the Aztec empire. This settlement eventually[when?] grew into the city now known as Veracruz ("True Cross").

During this same period, soon after he arrived, Cortés was welcomed by representatives of the Aztec Emperor, Moctezuma II. Gifts were exchanged, but Cortés ultimately attempted to frighten the Aztec delegation with a display of firepower. He also challenged the Aztec representatives to combat, but they quickly left the area so they could report to Moctezuma. Following this first meeting, more ambassadors from the Emperor returned, bearing many more gifts, including gold (which the Aztecs did not value highly). Although they attempted to dissuade Cortés from visiting Tenochtitlan, the lavish gifts and the polite, welcoming remarks only encouraged El Caudillo to continue his march on the capital of the empire. Throughout most of his march, the ambassadors of Moctezuma accompanied the Spanish force, and undoubtedly reported faithfully to Moctezuma.

Scuttling the fleet & Aftermath

Those of his men still loyal to the Governor of Cuba conspired to seize a ship and escape to Cuba, but Cortés moved swiftly to squash their plans. Two ringleaders were condemned to be hanged; two were lashed, and one had his foot mutilated. To make sure such a mutiny did not happen again, he decided to scuttle his ships, on the pretext that they were no longer seaworthy. There is a popular misconception that the ships were burned rather than sunk.

This misconception has been attributed to the reference made by Cervantes de Salazar in 1546 as to Cortés burning his ships.[33] This may have also come from a mistranslation of the version of the story written in Latin.[34]

With all of his ships scuttled, except for one small ship with which to send his representatives and booty to the King of Spain, Cortés effectively stranded the expedition in Mexico. However, it did not completely end the aspirations of those members of his company who remained loyal to the Governor of Cuba. Cortés then led his band inland towards the fabled Tenochtitlan. The last seaworthy ship was loaded with the Royal Fifth (the King of Spain claimed 20% of all spoils) of the Aztec treasure they had obtained so far in order to speed up Cortés's claim to the governorship.

In addition to the Spaniards, Cortés force now included 40 Cempoalan warrior chiefs and at least 200 other natives whose task was to drag the cannon and carry supplies. The Cempoalans were accustomed to the hot climate of the coast, but they suffered immensely from the cold of the mountains, the rain, and the hail as they marched towards Tenochtitlan.

Alliance with Tlaxcala

Cortés soon arrived at Tlaxcala, a confederacy of about 200 towns and different tribes, but without central government.

The Tlaxcalans initially greeted the Spanish with hostile action and the two sides fought a series of skirmishes and battles that ultimately forced the Spaniards up a hill where they were surrounded. Conquistador Bernal Díaz del Castillo describes this final battle between the Spanish forces and the Tlaxcalteca as surprisingly difficult. He writes that they probably would not have survived, had not Xicotencatl the Elder persuaded his son, the Tlaxcalan warleader, Xicotencatl the Younger, that it would be better to ally with the newcomers than to kill them. Their main city was Tlaxcala. After almost a century of fighting the Flower Wars, a great deal of hatred and bitterness had developed between the Tlaxcalans and the Aztecs. The Tlaxcalans believed that eventually the Aztecs would try to conquer them. It was just a matter of time before this tension developed into a real conflict. The Aztecs had already conquered most of the territory around Tlaxcala. It is possible that the Aztecs left Tlaxcala independent so that they would have a constant supply of war captives to sacrifice to their gods.[35] The sacrifice of a brave warrior was considered a greater gift to the gods than other common sacrifices.

On 18 September 1519, Cortés arrived in Tlaxcala and was greeted with joy by the rulers, who saw the Spanish as an ally against the Aztecs. Due to a commercial blockade by the Aztecs, Tlaxcala was poor, lacking, among other things, both salt and cotton cloth, so they could only offer Cortés and his men food and slaves. Cortés stayed twenty days in Tlaxcala, giving his men time to recover from their wounds. Cortés seems to have won the true friendship and loyalty of the senior leaders of Tlaxcala, among them Maxixcatzin and Xicotencatl the Elder, although he could not win the heart of Xicotencatl the Younger. The Spaniards agreed to respect parts of the city, like the temples, and reportedly took only the things that were offered to them freely.

As before with other native groups, Cortés preached to the Tlaxcalan leaders about the benefits of Christianity. Legends say that he convinced the four leaders of Tlaxcala to become baptized. Maxixcatzin, Xicotencatl the Elder, Citalpopocatzin and Temiloltecutl received the names of Don Lorenzo, Don Vicente, Don Bartolomé and Don Gonzalo.

It is impossible to know if these leaders understood the Catholic faith. In any event, they apparently had no problems in adding the Christian "Dios" (God in Spanish), the lord of the heavens, to their already complex pantheon of gods.

An exchange of gifts was made and thus began the highly significant and effective alliance between Cortés and Tlaxcala.[36]

Cortés marches to Cholula

Meanwhile, ambassadors from Moctezuma, who had been in the Spanish camp during the battles with the Tlaxcalans, continued to press Cortés to leave Tlaxcala, the "city of poor and thieves" and go to the neighbouring city of Cholula, which was under Aztec control. Cholula, founded in the year 2,[clarification needed] was one of the most important cities of Mesoamerica, the second largest, and probably the most sacred. Its huge pyramid (larger in volume than the great pyramids of Egypt) made it one of the most prestigious places of the Aztec religion. However, it appears that Cortés perceived Cholula more as a military threat to his rear guard as he marched to Tenochtitlan than a religious center. However, he sent emissaries first to try a diplomatic solution to entering the city.

The leaders of Tlaxcala urged Cortés to go instead to Huexotzingo, a city allied to Tlaxcala. Cortés, who had not yet decided to start a war with the Aztec Empire, decided to offer a compromise. He accepted the gifts of the Aztec ambassadors, but also accepted the offer of the Tlaxcalans to provide porters and warriors. He sent two men, Pedro de Alvarado, and Bernardino Vázquez de Tapia, on foot (he did not want to spare any horses), directly to Tenochtitlan, as ambassadors and to scout a route.

On 12 October 1519, Cortés and his men, accompanied by about 1,000 Tlaxcalteca, marched to Cholula.

Massacre of Cholula

There are contradictory reports about what happened at Cholula. Moctezuma had apparently decided to resist with force the advance of Cortés and his troops, and it seems that Moctezuma ordered the leaders of Cholula to try to stop the Spaniards. Cholula had a very small army, because as a sacred city they put their confidence in their prestige and their gods. According to the chronicles of the Tlaxcalteca, the priests of Cholula expected to use the power of Quetzalcoatl, their primary god, against the invaders.

Cortés and his men entered Cholula without active resistance. However, they were not met by the city leaders and were not given food and drink. Spanish soldiers reported that fortifications were being constructed around the city. The Tlaxcalans were warning the Spaniards that an Aztec army was marching on the city. Finally, La Malinche informed Cortés, after talking to the wife of one of the lords of Cholula, that the locals planned to murder the Spaniards in their sleep. Although he did not know if the rumor was true or not, Cortés ordered a pre-emptive strike, urged on by the Tlaxcalans, the enemies of the Cholulans. Cortés confronted the city leaders in the main temple alleging that they were planning to attack his men. They admitted that they had been ordered to resist by Moctezuma, but they claimed they had not followed his orders. Regardless, on command, the Spaniards seized and killed many of the local nobles to serve as a lesson. They seized the Cholulan leaders Tlaquiach and Tlalchiac and then ordered the city set fire. The troops started in the palace of Xacayatzin, and then on to Chialinco and Yetzcoloc. In letters to his King, Cortés claimed that in three hours time his troops (helped by the Tlaxcalans) killed 3,000 people and burned the city.[37] Another witness, Vázquez de Tapia, claimed the death toll was as high as 30,000. Of course, the reports by the Spaniards were usually gross exaggerations. Since the women and children, and many men, had already fled the city, it is unlikely that so many were killed. Regardless, the massacre of the nobility of Cholula was a notorious chapter in the conquest of Mexico.

The Azteca and Tlaxclateca histories of the events leading up to the massacre differ. The Tlaxcalteca claimed that their ambassador Patlahuatzin was sent to Cholula and had been tortured by the Cholula. Thus, Cortés was avenging him by attacking Cholula. (Historia de Tlaxcala, por Diego Muñoz Camargo, lib. II cap. V. 1550).

The Azteca version put the blame on the Tlaxcalteca claiming that they resented Cortés going to Cholula instead of Huexotzingo.[38]

The massacre had a chilling effect, to say the least, on the other city states and groups affiliated with the Aztecs, as well as the Aztecs themselves. Tales of the massacre convinced the other cities in the Aztec Empire to entertain seriously Cortés' proposals rather than risk the same fate.

Cortés then sent emissaries to Moctezuma with the message that the people of Cholula had treated him with disrespect and had therefore been punished. Cortés' message continued that the Aztecs need not fear his wrath if Moctezuma treated him with respect and gifts of gold.

In one of his responses to Cortés, Moctezuma blamed the commanders of the local Aztec garrison for the resistance in Cholula, and recognizing that his long-standing attempts to dissuade Cortés from coming to Tenochtitlan with gifts of gold and silver had failed, Moctezuma finally invited the Spaniards to visit his capital city, according to Spanish sources.

Tenochtitlan

On 8 November 1519 after the fall of Cholula, Cortés and his forces arrived at the outskirts of Tenochtitlan, the island capital of the Mexica-Aztecs. It is believed that the city was one of the largest in the world at that time .[citation needed] Of all the cities in Europe, only Constantinople was larger than Tenochtitlan. The most common estimates put the population at around 60,000 to over 300,000 people. The largest city in Spain, for example, was Seville, which had a population of only 30,000.

Cortés welcomed by Moctezuma

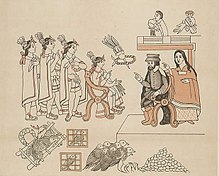

According to the Aztec chronicles recorded by Sahagún, the Aztec ruler Moctezuma II welcomed Hernán Cortés, El Caudillo, with great pomp. Sahagún reports that Moctezuma welcomed Cortés to Tenochtitlan on the Great Causeway into the "Venice of the West".[citation needed] Other scholars[who?] doubt that the meeting ever took place.[citation needed]

A fragment of the greetings of Moctezuma says: "My lord, you have become fatigued, you have become tired: to the land you have arrived. You have come to your city: Mexico, here you have come to sit on your place, on your throne. Oh, it has been reserved to you for a small time, it was conserved by those who have gone, your substitutes... This is what has been told by our rulers, those of whom governed this city, ruled this city. That you would come to ask for your throne, your place, that you would come here. Come to the land, come and rest: take possession of your royal houses, give food to your body."[39]

According to Sahagún's manuscript, Moctezuma personally dressed Cortés with flowers from his own gardens, the highest honor he could give, although probably Cortés did not understand the significance of the gesture. In turn, Cortés attempted to embrace the Emperor but was restrained by a courtier.

Some historians[citation needed] are skeptical of Sahagun's account that Moctezuma personally met Cortés on the Great Causeway because of the many proscriptions and prohibitions regarding the emperor vis-à-vis his subjects. For instance, when Moctezuma dined, he ate behind a screen so as to shield him from his court and servants. There were various restrictions on seeing and touching his person.

This contradiction between "the arrogant emperor" and the "humble servant of Quetzalcoatl" has been problematic for historians to explain and has led to much speculation. However, all the proscriptions and prohibitions regarding Moctezuma and his court had been established by Moctezuma and were not part of traditional Aztec customs. Those prohibitions had already caused friction between Moctezuma and the pillis (noble classes). There is even an Aztec legend in which Huemac, the legendary last lord of Tollan Xicotitlan, instructed Moctezuma to live humbly and eat only the food of the poor, to divert a future catastrophe. Thus, it seems out of character for Moctezuma to violate rules that he himself had promulgated. Yet, as supreme ruler, he had the power to break his own rules.

Moctezuma had the royal palace of Axayácatl prepared to house the Spanish and their 3000 Tlaxcalan allies. Later the same day that the Spanish expedition and their allies entered Tenochtitlan, Moctezuma came to visit Cortés and his men. What happened in this second meeting remains controversial. According to several Spanish versions, some written years or decades later, Moctezuma first repeated his earlier, flowery welcome to Cortés on the Great Causeway, but then went on to explain his view of what the Spanish expedition represented in terms of Aztec tradition and lore, including the idea that Cortés and his men (pale, bearded men from the east) were the return of characters from Aztec legend. At the end of this explanation, the Emperor pledged his fealty to the King of Spain and accepted Cortés as the King's representative. This supposed oath is important because it gave Cortés the legal basis for claiming that any subsequent revolt against his forces constituted treason against the King of Spain. It is quite possible that Cortés and his interpreters twisted the Emperor's words to suit his purposes. (Thomas, p. 284)

Cortés later asked Moctezuma to provide more gifts of gold to demonstrate his fealty as a vassal of Charles V. Cortés also demanded that the two large idols be removed from the main temple pyramid in the city, the human blood scrubbed off, and shrines to the Virgin Mary and St. Christopher be set up in their place. All his demands were met, further giving credence to the concept that Moctezuma had accepted the King of Spain as his liege lord.

Using the killing of several Spanish soldiers, including his commander in Veracruz, and their native allies along the coast by the Aztec garrison as a pretext, Cortés seized Moctezuma on 14 November 1519 and made him his prisoner as insurance against any further resistance and demanded an enormous payment of gold, which was duly delivered. From this date, until the end of May 1520, Moctezuma lived with Cortés in the palace of Axayácatl. However, he continued to act as Emperor, subject to Cortés' overall control. He was also forced to take another, more formal oath of allegiance to the King of Spain. However, Moctezuma maintained private lines of communication with his subordinates across the empire. During the period of his imprisonment, Moctezuma apparently began identifying with his captors, whom he found interesting and entertaining.

Knowing that their leader was a captive and being required to feed not just a band of Spaniards but thousands of their Tlaxcalteca allies, the populace of Tenochtitlan began to feel a strain weighing upon them.[citation needed] Many of the nobility rallied around Cuitláhuac, the brother of Moctezuma and his heir-apparent, however, most of them could take no overt action against the Spanish unless the order was given by the Emperor.

Defeat of de Narváez

In April 1520, Cortés received news from the coast that a much larger party of Spaniards under the command of Pánfilo de Narváez had arrived. Narváez had been sent by Governor Velázquez from Cuba not only to supersede Cortés, but to arrest him and bring him to trial in Cuba for insubordination, mutiny, and treason.

Cortés' response was arguably one of the most daring of his many exploits. Some describe it as absolutely reckless, but Cortés had few other options.[citation needed] If arrested and convicted, he could have been executed.

Leaving one hundred and forty Spaniards and some Tlaxcalans under the command of Pedro de Alvarado to hold Tenochtitlan, Cortés set out against Narváez, who had nine hundred soldiers. Cortés was able to gather up some reinforcements as he approached the coast, but probably mustered only two hundred and sixty men by the time he engaged his opponent. Using this much smaller force, Cortés surprised his antagonist with a surprise night attack during which his men took Narváez prisoner. After Cortés told the defeated soldiers about the city of gold, Tenochtitlan, and bought off their commanders with promises of vast riches, they agreed to join him. (Narváez lost an eye in the battle and was eventually killed during the exploration of Florida.)

The tactic used by Cortés was an act of desperation, but one of the secrets of Cortés' overall success lay in his quick movements, for which Narváez was not prepared. So too was his rapid return to Tenochtitlan, by which he would surprise the Aztecs who had rebelled against the Spaniards and had been able to besiege Alvarado, his men, and Moctezuma in the palace.

Cortés then had to lead the combined forces on an arduous trek back over the Sierra Madre Oriental. Years later, when asked what the new land was like, Cortés crumpled up a piece of parchment, then spread it part way out: "Like this", he said.

The Aztec response

When Cortés returned to Tenochtitlan in late May, he found that Alvarado and his men had attacked and killed many of the Aztec nobility (see The Massacre in the Main Temple) during a religious festival. Alvarado's explanation to Cortés was that the Spaniards had learned that the Aztecs planned to attack the Spanish garrison in the city once the festival was complete, so he had launched a preemptive attack. Considerable doubt has been cast by different commentators on this explanation, which may have been self-serving rationalization on the part of Alvarado, who may have attacked out of fear (or greed) where no immediate threat existed. In any event, the population of the city rose en masse after the Spanish attack. Fierce fighting ensued, and the Aztec troops besieged the palace housing the Spaniards and Moctezuma. At one point, Moctezuma was able to arrange something of a truce, but sporadic fighting was continuing when Cortés and his new army returned from the coast.

The nobility of Tenochtitlan chose a new leader, Cuitláhuac, and the attacks on the Spaniards resumed. Cortés ordered Moctezuma to speak to his people from a palace balcony and persuade them to let the Spanish return to the coast in peace. Moctezuma was jeered and stones were thrown at him, injuring him badly. Moctezuma died a few days later (accounts as to who was actually guilty of his death do not agree; Aztec informants in later years insisted that Cortés had him killed.) After his death Cuitláhuac was selected as Huey Tlatoani (Emperor).

The Spaniards and their allies had to flee the city, as the population of Tenochtitlan had risen against them and their situation could only deteriorate. Because the Aztecs had removed the bridges over the gaps in the causeways that linked the city to the mainland, Cortés' men constructed a portable bridge with which to cross the openings. On the rainy night of 1 July 1520, the Spaniards and their allies set out for the mainland via the causeway to Tlacopan. They placed the portable bridge in the first gap, but at that moment their movement was detected and Aztec forces attacked, both along the causeway and by means of canoes on the lake. The Spanish were thus caught on a narrow road with water or buildings on both sides.

The retreat quickly turned into a rout. The Spanish discovered that they could not remove their portable bridge unit from the first gap, and so had no choice but to leave it behind. The bulk of the Spanish infantry, left behind by Cortés and the other horsemen, had to cut their way through the masses of Aztec warriors opposing them. Many of the Spaniards, weighed down by their armor and booty, drowned in the causeway gaps or were killed by the Aztecs. Much of the wealth the Spaniards had acquired in Tenochtitlan was lost. During the escape, Alvarado is alleged to have jumped across one of the narrower channels. The channel is now a street in Mexico City, called "Puente de Alvarado" (Alvarado's Bridge), because it seemed Alvarado escaped across an invisible bridge. (He may have been walking on the bodies of those soldiers and attackers who had preceded him, given the shallowness of the lake.)

In this retreat the Spaniards suffered heavy casualties, losing probably more than 600 of their own number and a thousand or more Tlaxcalan warriors. Several Aztec noblemen loyal to Cortés and their families also perished. It is said that Cortés, upon reaching the mainland at Tlacopan, wept over their losses. This episode is called "La Noche Triste" (The sad night), and the old tree ("El árbol de la noche triste") where Cortés allegedly cried is still a monument in Mexico.

Spaniards find refuge in Tlaxcala

The Aztecs pursued and harassed the Spanish, who, guided by their Tlaxcalan allies, moved around Lake Zumpango toward sanctuary in Tlaxcala. On 8 July 1520 the Aztecs attempted to destroy the Spanish for good at the battle of Otumba. Although hard-pressed, the Spanish infantry was able to hold off the overwhelming numbers of enemy warriors, while the Spanish cavalry under the leadership of Cortés charged through the enemy ranks again and again. When Cortés and his men killed one of the Aztec leaders, the Aztecs broke off the battle and left the field. The Spanish were able then to complete their escape to Tlaxcala. There they were given assistance and comfort, since almost all of them were wounded, and only twenty horses were left. The Aztecs sent emissaries and asked the Tlaxcalteca to turn over the Spaniards to them, but Tlaxcala refused.

While the Flower Wars had started as a mutual agreement[citation needed], the Tlaxcala and the Aztecs had now become entangled in a true war, a battle to the end. The Aztecs had conquered almost all the territories around Tlaxcala, closing off all commerce with them. The Tlaxcalteca knew that the Aztecs would try to conquer Tlaxcala itself. Therefore, most of the Tlaxcalan leaders were receptive when Cortés, once his men had the chance to recuperate, proposed an joint campaign to conquer Tenochtitlan. Xicotencatl the Younger, however, opposed the idea, and instead connived with the Aztec ambassadors in an attempt to form a new alliance with the Mexicas, since the Tlaxcalans and the Aztecs shared the same language and religion. Finally the elders of Tlaxcala accepted Cortés' offer under stringent conditions: they would not be required to pay any form of tribute to the Spaniards, they should receive the city of Cholula in return, they would have the right to build a fortress in Tenochtitlan, so they could have control of the city, and they would receive a share of the spoils of war.

Cortés also knew that he had to separate the Aztec from their other allies in the Valley of Mexico, whether by diplomacy or by force.

Siege of Tenochtitlan

The joint forces of Tlaxcala and Cortés proved to be formidable. One by one they took over most of the cities under Aztec control, some in battle, others by diplomacy. In the end, only Tenochtitlan and the neighboring city of Tlatelolco remained unconquered or not allied with the Spaniards.

Cortés then approached Tenochtitlan and mounted a siege of the city that involved cutting the causeways from the mainland and controlling the lake with armed brigantines constructed by the Spanish and transported overland to the lake. The siege of Tenochtitlan lasted eight months. The besiegers cut off the supply of food and destroyed the aqueduct carrying water to the city. Even worse, many of the inhabitants of the city had been ravaged by the effects of smallpox, which spread rapidly across most of Central Mexico (and beyond), killing hundreds of thousands, including the new Aztec emperor, Cuitláhuac. In fact, it is estimated that a third of the inhabitants of the entire valley died in less than six months from the new disease brought by the Spaniards to Tenochtitlan the year before.

Despite the stubborn Aztec resistance organized by their new emperor, Cuauhtémoc, the cousin of Moctezuma II, Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco fell on 13 August 1521, during which the Emperor was captured trying to escape the city in a canoe. The siege of the city and its defense had both been brutal. Largely because he wanted to present the city to his king and emperor, Cortés had made several attempts to end the siege through diplomacy, but all offers were rejected. During the battle the defenders cut the beating hearts from seventy Spanish prisoners-of-war at the altar to Huitzilopochtli,[40] an act that infuriated the Spaniards. In the ensuing sack of what remained of the city, the Tlaxcalan warriors spared few.

Cortés is one of the best exploreres of all time becuase he got all the b@#^hes then ordered the Aztec gods in the temples taken down and replaced with icons of Christianity. He also announced that the temple would never again be used for human sacrifice. Human sacrifice and reports of cannibalism, common among the natives of the Aztec Empire, had been major reason motivating Cortés and encouraging his soldiers to avoid surrender while fighting to the death.

Tenochtitlan had been almost totally destroyed by fire and cannon shot during the siege, and once it finally fell the Spanish continued its destruction, as they soon began to establish the foundations of what would become Mexico City on the site. The surviving Aztec people were forbidden to live in Tenochtitlan and the surrounding isles, and were banished to live in Tlatelolco.

Integration into the Spanish Empire

The Council of the Indies was constituted in 1524 and the first Audiencia in 1527. In 1535, Charles V the Holy Roman Emperor (who was, as king of Spain, known as Charles I), named Spanish nobleman, don Antonio de Mendoza, the first viceroy of New Spain. Mendoza was entirely loyal to the Spanish crown, unlike conqueror Hernán Cortés, who had demonstrated that he was independent-minded and defied official orders when he threw off the authority of governor Diego Velázquez in Cuba. The name "New Spain" had been suggested by Cortés and was later confirmed officially by Mendoza.

Later Wars of Conquest

The fall of Tenochtitlan usually is referred to as the main episode in the process of the conquest of Mesoamerica. However, this process was much more complex and took longer than the three years that it took Cortés to conquer Tenochtitlan. It took almost 60 years of wars for the Spaniards to suppress the resistance of the Indian population of Mesoamerica.

Chichimec Wars

After the Spanish conquest of central Mexico, expeditions were sent further northward in Mesoamerica, to the region known as La Gran Chichimeca. The expeditions under Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán were particularly harsh on the Chichimeca population, causing them to rebel under the leadership of Tenamaxtli and thus launch the Mixton War.

In 1540, the Chichimecas fortified Mixtón, Nochistlán, and other mountain towns then besieged the Spanish settlement in Guadalajara. The famous conquistador Pedro de Alvarado, coming to the aid of acting governor Cristóbal de Oñate, led an attack on Nochistlán. However, the Chichimecas counter-attacked and Alvarado's forces were routed. Under the leadership of Viceroy Don Antonio de Mendoza, the Spanish forces and their Indian allies ultimately succeeded in recapturing the towns and suppressing resistance. However, fighting did not completely come to a halt in the ensuing years.

In 1546, Spanish authorities discovered silver in the Zacatecas region and established mining settlements in Chichimeca territory which altered the terrain and the Chichimeca traditional way of life. The Chichimeca resisted the intrusions on their ancestral lands by attacking travelers and merchants along the "silver roads." The ensuing Chichimeca War (1550–1590) would become the longest and costliest conflict between Spanish forces and indigenous peoples in the Americas. The attacks intensified with each passing year. In 1554, the Chichimecas inflicted a great loss upon the Spanish when they attacked a train of sixty wagons and captured more than 30,000 pesos worth of valuables. By the 1580s, thousands had died and Spanish mining settlements in Chichimeca territory were continually under threat. In 1585, Don Alvaro Manrique de Zúñiga, Marquis of Villamanrique, was appointed viceroy. The viceroy was infuriated when he learned that some Spanish soldiers had begun supplementing their incomes by raiding the villages of peaceful Indians in order to sell them into slavery. With no militaristic end to the conflict in sight, he was determined to restore peace to that region and launched a full-scale peace offensive by negotiating with Chichimeca leaders and providing them with lands, agricultural supplies, and other goods. This policy of "peace by purchase" finally brought an end to the Chichimeca War.[41]

Conquest of the Yucatán Peninsula

The Spanish conquest of Yucatán took almost 170 years. The whole process could have taken longer were it not for three separate epidemics that took a heavy toll on the Native Americans, killing almost 75% of the population and causing the collapse of Mesoamerican cultures. Some believe that Old World diseases like smallpox caused the death of 90 to 95 percent of the native population of the New World.[42]

The Aztecs under Spanish rule

The Aztec Empire ceased to exist with the Spanish final conquest of Tenochtitlan in August 1521. The empire had been composed of separate city-states that had either allied with or been conquered by the Mexica of Tenochtitlan, and rendered tribute to the Mexica while maintaining their internal ruling structures. Those polities now came under Spanish rule, also retaining their internal structures of ruling elites, tribute paying commoners, and land holding and other economic structures largely intact. Two key works by historian Charles Gibson, Tlaxcala in the Sixteenth Century (1952)[43] and his vastly important monograph The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule: A History of the Indians of the Valley of Mexico, 1519-1810 (1964)[44] were crucial in reshaping the understanding of the history of the indigenous and their communities from the Spanish conquest to Mexican the 1810 Mexican independence era.

Scholars who were part of a branch of Mesoamerican ethnohistory, more recently called the New Philology have, using indigenous texts in the indigenous languages, been able to examine in considerable detail how the indigenous lived during the era of Spanish colonial rule. A major work that utilizes colonial-era indigenous texts as its main source is James Lockhart's The Nahuas After the Conquest: Postconquest Central Mexican History and Philology.[45] Key to understanding how considerable continuity of pre-conquest indigenous structures was possible was the Spanish colonial utilization of the indigenous nobility. In the colonial era, the indigenous nobility were largely recognized as nobles by the Spanish colonial regime, with privileges including the noble Spanish title don for noblemen and doña for noblewomen. To this day, the title of Duke of Moctezuma is held by a Spanish noble family. A few of the indigenous nobility learned Spanish. Spanish friars taught indigenous scribes to write their own languages in Latin letters, which soon became a self-perpetuating tradition at the local level.[46] Their surviving writings are crucial in our knowledge of colonial era Nahuas.

The first mendicants in central Mexico, particularly the Franciscans and Dominicans learned the indigenous language of Nahuatl, in order to evangelize in indigenous in their native tongue. Early mendicants created texts in order to forward the project of Christianization. Particularly important were the 1571 Spanish-Nahuatl dictionary compiled by Franciscan Fray Alonso de Molina,[47] and his 1569 bilingual Nahuatl-Spanish confessional manual for priests.[48] A major project by the Franciscans in Mexico was the compilation of knowledge on Nahua religious beliefs and culture that friar Bernardino de Sahagún, oversaw, using indigenous informants, resulting in a number of important texts and culminating in a 12 volume text, The General History of the Things of New Spain published in English as the Florentine Codex. The Spanish crown via the Council of the Indies and the Franciscan order in the late sixteenth century became increasingly hostile to works by religious in the indigenous languages, concerned that they were heretical and impediment to the Indians' true conversion.[49]

To reward to Spaniards who participated in the conquest what is now contemporary Mexico, the Spanish crown authorized grants of native labor in particular indigenous communities via the Encomienda. The indigenous were not slaves, chattel bought and sold or removed from their home community, but the system was one of forced labor. The indigenous of Central Mexico had practices rendering labor and tribute products to their polity's elites and those elites to the Mexica overlords in Tenochtitlan, so the Spanish system of encomienda was built on pre-existing patterns.

The Spanish conquerors in Mexico during the early colonial era lived off the labor of the indigenous. Due to some horrifying instances of abuse against the indigenous peoples, Bishop Bartolomé de las Casas suggested importing black slaves to replace them. Las Casas later repented when he saw the even worse treatment given to the black slaves.[50]

The other discovery that perpetuated this system of indigenous forced labor was extensive silver mines discovered at Potosi, in Upper Peru (now Bolivia) and other places that were worked for hundreds of years by forced native labor and contributed most of the wealth that flowed to Spain. Spain spent enormous amounts of this wealth hiring mercenaries to fight the Protestant Reformation and to halt the Turkish invasions of Europe. The silver was used to purchase goods, as European manufactured goods were not in demand in Asia and the Middle East. The Manila Galleon brought in far more silver direct from South American mines to China than the overland Silk Road, or even European trade routes in the Indian oceans could.

The Aztec education system was abolished and replaced by a very limited church education. Even some foods associated with Mesoamerican religious practice, such as amaranth, were forbidden.[citation needed]

In the 16th century, perhaps 240,000 Spaniards entered American ports. They were joined by 450,000 in the next century.[51] Unlike the English-speaking colonists of North America, the majority of the Spanish colonists were single men who married or made concubines of the natives,[citation needed] and were even encouraged to do so by Queen Isabella during the earliest days of colonization. As a result of these unions, as well as concubinage [citation needed] and secret mistresses, mixed race individuals known as "Mestizos" came into being.

Cultural depictions

The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire is the subject of an opera, La Conquista (2005) and of a set of six symphonic poems, La nueva España (1992–99) by Italian composer Lorenzo Ferrero.

Cortés's conquest has been depicted in numerous television documentaries. These include in an episode of Engineering an Empire as well as in the BBC series Heroes and Villains, with Cortés being portrayed by Brian McCardie. The expedition was also partially included in the animated film The Road to El Dorado as the main characters Tulio and Miguel end up as stowaways on Hernán Cortés' fleet to Mexico. Here Cortés is a merciless and ambitious villain, leading a quest to find El Dorado the legendary city of gold in the New World, he is voiced by Jim Cummings.

The aftermath of the Spanish conquest, including the Aztecs' struggle to preserve their cultural identity, is the subject of the acclaimed Mexican feature film, The Other Conquest, directed by Salvador Carrasco.

See also

Notes

- ^ The title of conqueror Bernal Díaz del Castillo's major work, The True History of the Conquest of Mexico and William Hickling Prescott's nineteenth-century bestselling story of the conquest is entitled The History of the Conquest of Mexico both authors take for granted that what is referred to is the conquest of the Aztecs.

- ^ James Lockhart and Stuart Schwartz, Early Latin America: A History of Colonial Spanish America and Brazil. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983. See especially chapter 3, "From islands to mainland: the Caribbean phase and subsequent conquests."

- ^ James Lockhart and Stuart Schwartz,Early Latin America: A History of Colonial Spanish America and Brazil New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983, p. 80

- ^ Francisco López de Gómara, Cortés: The Life of the Conqueror by His Secretary, translated by Lesley Byrd Simpson. Berkeley: University of California Press 1964, pp. 207-08.

- ^ Ida Altman, et al. The Early History of Greater Mexico, Pearson, 2003, p. 59.

- ^ Sarah Cline, "Conquest Narratives," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerica, David Carrasco, ed. New York: Oxford University Press 2001, vol. 1, p 248

- ^ Ida Altman, S.L. (Sarah) Cline, and Javier Pescador, The Early History of Greater Mexico, chapter 4, "Narratives of the Conquest." Pearson, 2003, pp. 73-96.

- ^ Patricia de Fuentes, ed. The Conquistadors: First-Person Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1993. Previously published by Orion Press 1963.

- ^ "Two Letters of Pedro de Alvarado" in The Conquistadors, Patricia de Fuente, editor and translator. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1993, pp. 182-196.

- ^ "The Cronicle of the Anonymous Conquistador" in The Conquistadors: First-person Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico Patricia de Fuente, (editor and trans). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1993, pp. 165-181.

- ^ James Lockhart, We People Here, University of California Press 1991, pp. 289-297

- ^ Fernando Alva Ixtlilxochitil, Ally of Cortés: Account 13 of the Coming of the Spaniards and the Beginning of the Evangelical Law. Douglass K. Ballentine, translator. El Paso: Texas Western Press 1969

- ^ Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, The Conquest of New Spain, 1585 Revision translated by Howard F. Cline, with an introduction by S.L. Cline. University of Utah Press 1989.

- ^ Fray Diego Durán, The History of the Indies of New Spain[1581], Trans., annotated, and with an introduction by Doris Heyden. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994.

- ^ James Lockhart, We People Here: Nahuatl Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico, University of California Press 1991,pp. 256-273.

- ^ Miguel León-Portilla, 'The Broken Spears: The Aztec Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico. Boston: Beacon Press, 1992.

- ^ William Hickling Prescott, History of the Conquest of Mexico, introduction by James Lockhart. New York: The Modern Library, 2001

- ^ S.L. Cline "Introduction," History of the Conquest of New Spain, 1585 Revision by Bernardino de Sahagún, Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press 1989.

- ^ Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, General History of the Things of New Spain (The Florentine Codex). Book 12. Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles Dibble, translators. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

- ^ Camilla Townsend, "Burying the White Gods: New Perspectives on the Conquest of Mexico" The American Historical ReviewVol. 108, No. 3 (June 2003), pp. 659-687

- ^ Restall, Matthew. Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest. Oxford University Press (2003), ISBN 0-19-516077-0

- ^ Schwartz, Stuart B., ed. Victors and Vanquished: Spanish and Nahua Views of the Conquest of Mexico. Boston: Bedforf, 2000.

- ^ a b Hassig, Ross, Mexico and the Spanish Conquest. Longman: London and New York, 1994. p. 45.

- ^ a b Ida Altman, S.L. (Sarah) Cline, The Early History of Greater Mexico, Pearson, 2003, p. 54

- ^ Hassig, Ross, Mexico and the Spanish Conquest. Longman: London and New York, 1994. p. 46.

- ^ Thomas, Hugh. Conquest: Montezuma, Cortés, and the fall of Old Mexico p. 141

- ^ James Lockhart, Spanish Peru, 1532-1560., Madison: University of Wisconsin Press 1968.

- ^ Guerrero is reported to have responded, "Brother Aguilar, I am married and have three children, and they look on me as a Cacique here, and a captain in time of war [...] But my face is tattooed and my ears are pierced. What would the Spaniards say if they saw me like this? And look how handsome these children of mine are!" (p.60).

- ^ Later in the voyage a young woman, La Malinche, would be given to Cortés as a slave by the Chontal Maya inhabitants of the Tabasco coast. La Malinche spoke Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs and a regional lingua franca, as well as Chontal Maya, which was also understood by Aguilar. Cortés would be able to use the two of them to communicate with the central Mexican peoples and the Aztec court. See See The Conquest of New Spain, pp.85–87.

- ^ "Conquistadors - Cortés". PBS. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ Tuck, Jim (9 October 2008). "Affirmative action and Hernán Cortés (1485–1547) : Mexico History". Mexconnect.com. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ See: Restall, Matthew. Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest. Oxford University Press: Oxford and New York, 2003.

- ^ Matthew Restall, "Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest", 2003

- ^ Cortés Burns His Boats pbs.org

- ^ "Conquistadors - Cortés". PBS. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ Hugh Tomas, The conquest of Mexico, 1994.

- ^ "Empires Past: Aztecs: Conquest". Library.thinkquest.org. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ Informantes de Sahagún: Códice Florentino, lib. XII, cap. X.; Spanish version by Angel Ma. Garibay K.

- ^ Anonymous informants of Sahagún, Florentine codex, book XII, chapter XVI, translation from Nahuatl by Angel Ma. Garibay.

- ^ Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Historia verdadera de la conquista de Nueva Espana, capitulo CLII

- ^ "John P. Schmal". Somosprimos.com. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ "The Story Of... Smallpox – and other Deadly Eurasian Germs". Pbs.org. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ Charles Gibson, Tlaxcala in the Sixteenth Century, New Haven: Yale University Press 1952

- ^ Charles Gibson, The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule: A History of the Indians of the Valley of Mexico, 1519-1810, Stanford: Stanford University Press 1964.

- ^ James Lockhart, The Nahuas After the Conquest: Postconquest Central Mexican History and Philology, Stanford: Stanford University Press 1992.

- ^ Frances Karttunen, "Aztec Literacy," in George A. Coller et al.,, eds. The Inca and Aztec States, pp. 395-417. New York: Academic Press 1982.

- ^ Fray Alonso de Molina, Vocabulario en lengua cstellana y mexicana y mexcana y castellana(1571), Mexico: Editorial Porrúa, 1970

- ^ Fray Alonso de Molina, Confessionario mayor en la lengua castellana y mexicana (1569), With an introduction by Roberto Moreno. Mexico: Instituto de Investigaciones Filológicos, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricos, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- ^ Howard F. Cline, "Evolution of the Historia General" in Handbook of Middle American Indians, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources, vol. 13, part 2, Howard F. Cline, volume editor, Austin: University of Texas Pres, 1973 p.196.

- ^ Blackburn 1997: 136; Friede 1971: 165–166

- ^ Axtell, James (September–October 1991). "The Columbian Mosaic in Colonial America". Humanities. 12 (5): 12–18. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)

References

Primary sources

- Anonymous Conqueror, the (1917) [1550]. Narrative of Some Things of New Spain and of the Great City of Temestitan. Marshall Saville (trans). New York: The Cortés Society.

- Hernán Cortés, Letters – available as Letters from Mexico translated by Anthony Pagden (1986) ISBN 0-300-09094-3

- Francisco López de Gómara, Hispania Victrix; First and Second Parts of the General History of the Indies, with the whole discovery and notable things that have happened since they were acquired until the year 1551, with the conquest of Mexico and New Spain

- Bernal Díaz del Castillo, The Conquest of New Spain – available as The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico: 1517-1521 ISBN 0-306-81319-X

- León-Portilla, Miguel (Ed.) (1992) [1959]. The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico. Ángel María Garibay K. (Nahuatl-Spanish trans.), Lysander Kemp (Spanish-English trans.), Alberto Beltran (illus.) (Expanded and updated ed.). Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-5501-8.

Secondary sources

- History of the Conquest of Mexico, with a Preliminary View of Ancient Mexican Civilization, and the Life of the Conqueror, Hernando Cortes By William H. Prescott ISBN 0-375-75803-8

- Conquest: Cortés, Montezuma, and the Fall of Old Mexico by Hugh Thomas (1993) ISBN 0-671-51104-1

- Cortés and the Downfall of the Aztec Empire by Jon Manchip White (1971) ISBN 0-7867-0271-0

- The Rain God cries over Mexico by László Passuth

- Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest by Matthew Restall, Oxford University Press (2003) ISBN 0-19-516077-0

- The Conquest of America by Tzvetan Todorov (1996) ISBN 0-06-132095-1

- Time, History, and Belief in Aztec and Colonial Mexico by Ross Hassig, Texas University Press (2001) ISBN 0-292-73139-6

- The Aztecs of Central Mexico: An Imperial Society by Frances F. Berdan, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, (1982) ISBN 0-03-055736-4

- Mexico and the Spanish Conquest by Ross Hassig, Longman: London and New York, (1994) ISBN 0-582-06828-2

Additional Bibliography

- Chasteen, John Charles. Born in Blood and Fire: A Concise History of Latin America. New

York: W.W. Norton, 2011.

- Francisco Nunez de Pineda y Bascunan. “Happy Captivity.” In Born in Blood and Fire: Latin

American Voices, edited by John Charles Chasteen. 42-48. New York: W.W. Norton, 2011.

- Garofalo, Leo J., and Erin E. O'Connor. Documenting Latin America : Gender, Race, and

Empire, vol. 1. Boston: Prentice Hall, 2011.

- O'Connor, Erin, and Leo Garofalo. Mothers Making Latin America.

- Townsend, Camilla. Malintzin's Choices: An Indian Woman in the Conquest of Mexico.

Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2006.

External links

- Hernán Cortés on the Web – web directory with thumbnail galleries

- Catholic Encyclopedia (1911)

- Conquistadors, with Michael Wood – website for 2001 PBS documentary

- Ibero-American Electronic Text Series presented online by the University of Wisconsin Digital Collections Center

- La Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España Template:Es icon

- Articles needing examples from January 2014

- Use dmy dates from August 2010

- Aztec history

- Spanish conquests in the Americas

- 16th-century conflicts

- 1510s in Mexico

- 1520s in Mexico

- History of Mesoamerica

- New Spain

- Battles involving the Aztec Empire

- Colonial Mexico

- 1519 in Mexico

- 1520 in Mexico

- 1521 in Mexico

- 1521 in North America

- 1519 in New Spain

- 1520 in New Spain

- 1521 in New Spain