Spear

A spear is a pole weapon consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head. The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with fire hardened spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fastened to the shaft, such as flint, obsidian, iron, steel or bronze. The most common design for hunting or combat spears since ancient times has incorporated a metal spearhead shaped like a triangle, lozenge, or leaf. The heads of fishing spears usually feature barbs or serrated edges.

The word spear comes from the Old English spere, from the Proto-Germanic speri, from a Proto-Indo-European root *sper- "spear, pole". Spears can be divided into two broad categories: those designed for thrusting in melee combat and those designed for throwing (usually referred to as javelins).

The spear has been used throughout human history both as a hunting and fishing tool and as a weapon. Along with the axe, knife, and club it is one of the earliest and most important tools developed by early humans. As a weapon, it may be wielded with either one hand or two. It was used in virtually every conflict up until the modern era, where even then it continues on in the form of the bayonet, and is probably the most commonly used weapon in history.[1]

Origins

Spear manufacture and use is not confined to human beings. It is also practiced by the western chimpanzee. Chimpanzees near Kédougou, Senegal have been observed to create spears by breaking straight limbs off trees, stripping them of their bark and side branches, and sharpening one end with their teeth. They then used the weapons to hunt galagos sleeping in hollows.[2] Orangutans also have used spears to fish, presumably after observing humans fishing in a similar manner.[3]

Prehistory

Archaeological evidence found in present-day Germany documents that wooden spears have been used for hunting since at least 400,000 years ago,[4] and a 2012 study suggests that Homo heidelbergensis may have developed the technology about 500,000 years ago.[5] Wood does not preserve well, however, and Craig Stanford, a primatologist and professor of anthropology at the University of Southern California, has suggested that the discovery of spear use by chimpanzees probably means that early humans used wooden spears as well, perhaps, five million years ago.[6]

Neanderthals were constructing stone spear heads from as early as 300,000 BP and by 250,000 years ago, wooden spears were made with fire-hardened points.

From 200,000 BP onwards, Middle Paleolithic humans began to make complex stone blades with flaked edges which were used as spear heads. These stone heads could be fixed to the spear shaft by gum or resin or by bindings made of animal sinew, leather strips or vegetable matter. During this period, a clear difference remained between spears designed to be thrown and those designed to be used in hand-to-hand combat. By the Magdalenian period (c. 15000-9500 BC), spear-throwers similar to the later atlatl were in use.[7] O

Military

Spears were one of the most common personal weapons used in the Stone Age, and they remained in use as important military and hunting implements until the advent of firearms. They may be seen as the ancestor of such military weapons as the lance, the pilum, the halberd, the naginata, the glaive, the bill, and the pike. One of the earliest weapons fashioned by human beings and their ancestors, the spear is still used for hunting and fishing, and its influences still may be seen in current military gear such as the rifle-mounted bayonet.

Spears may be used as both a projectile and melee weapons. Spears used primarily for thrusting may be used with either one or two hands and tend to have heavier and sturdier designs than those intended exclusively for throwing. Those designed for throwing, often referred to as javelins, tend to be lighter and have a more streamlined head, and they may be thrown either by hand or with the assistance of a spear thrower such as the atlatl or woomera. From the atlatl dart, the arrow for use with bows eventually developed.

Ancient history

Infantry

Short, one-handed spears featuring socketed metal heads were used in conjunction with a shield by the earliest Bronze Age cultures. They were wielded in either single combat or in large troop formations. This tradition continued from the first Mesopotamian cultures, through the various ancient Egyptian dynasties, to the period of the Ancient Greek city states.

Africa

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2010) |

The spear probably originated in Africa sometime during the evolution of the genus Homo. It was an important part of the Nubian and ancient Egyptian military and continued to be used throughout African history even after the introduction of gunpowder. The most common kind of spear used in Africa is the assegai, which is usually thrown. Later, the Zulu people of eastern South Africa would become known for their particular skill with shortened thrusting spears called iklwa. These spears were designed for close combat and often were wielded in conjunction with a large oval shield. Advanced skills in close combat allowed the Zulu military to conquer much of southeast Africa.

Greeks

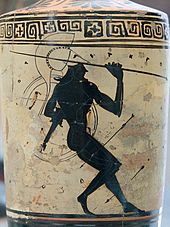

The spear is the main weapon of the warriors of Homer's Iliad. The use of both a single thrusting spear and two throwing spears are mentioned. It has been suggested that two styles of combat are being described; an early style, with thrusting spears, dating to the Mycenaean period in which the Iliad is set, and, anachronistically, a later style, with throwing spears, from Homer's own Archaic period.[8]

In the 7th century BC, the Greeks evolved a new close-order infantry formation, the phalanx.[9] The key to this formation was the hoplite, who was equipped with a large, circular, bronze-faced shield (hoplon) and a 7–9 ft. (2–2.75 m) spear with an iron head and bronze butt-spike (doru).[10] The hoplite phalanx dominated warfare among the Greek City States from the 7th into the 4th century BC.

The 4th century saw major changes. One was the greater use of peltasts, light infantry armed with spear and javelins.[11] The other was the development of the sarissa, a two-handed pike 18 ft. (5.5 m) in length, by the Macedonians under Phillip of Macedon and Alexander the Great.[12] The pike phalanx, supported by peltasts and cavalry, became the dominant mode of warfare among the Greeks from the late 4th century onward[13] until Greek military systems were supplanted by the Roman legions.

Cavalry

During this time the spear was also used by cavalry. The majority of ancient cavalry units were equipped either with javelins or a one-handed thrusting spear similar to that used by infantry. Some, however, used longer spears. The Macedonian xyston was 12–14 ft. (3.6–4.2 m) in length and could be used with one or two hands. The use of the two-handed kontos by heavily armoured soldiers on horseback, known as cataphracts, was developed first by nomadic eastern Iranian tribes and spread throughout the ancient world. These would be used to great effect by the Diadochi kingdoms and the Parthians and, later, by the Sassanians and Sarmatians. Later Roman and Byzantine armies also made use of these troops.

Romans

In the pre-Marian Roman armies the first two lines of battle, the hastati and principes, often fought with a sword called a gladius and pila, heavy javelins that were specifically designed to be thrown at an enemy to pierce and foul a target's shield. Originally the principes were armed with a short spear called a hasta, but these gradually fell out of use, eventually being replaced by the gladius. The third line, the triarii, continued to use the hasta.

From the late 2nd century BC, all legionaries were equipped with the pilum. The pilum continued to be the standard legionary spear until the end of the 2nd century AD. Auxilia, however, were equipped with a simple hasta and, perhaps, throwing spears. During the 3rd century AD, although the pilum continued to be used, legionaries usually were equipped with other forms of throwing and thrusting spear, similar to auxilia of the previous century. By the 4th century, the pilum had effectively disappeared from common use.[14]

Middle East and North Africa during Islamic period

Muslim warriors used a spear that was called an az-zaġāyah. Berbers pronounced it zaġāya, but the English term, derived from the Old French via Berber, is "assegai". It is a pole weapon used for throwing or hurling, usually a light spear or javelin made of hard wood and pointed with a forged iron tip.The az-zaġāyah played an important role during the Islamic conquest as well as during later periods, well into the 20th century. A longer pole az-zaġāyah was being used as a hunting weapon from horseback. The az-zaġāyah spread far into Sub-Saharan Africa as well as India, although these places already had their own variants of the spear. It was the weapon of choice during the Fulani jihad as well as during the Mahdist War in Sudan. It is still being used by Sikh Nihang in the Punjab as well as certain wandering Sufi ascetics (Derwishes).

European Middle Ages

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the spear and shield continued to be used by nearly all Western European cultures. Since a medieval spear required only a small amount of steel along the sharpened edges (most of the spear-tip was wrought iron), it was an economical weapon. Quick to manufacture, and needing less smithing skill than a sword, it remained the main weapon of the common soldier. The Vikings, for instance, although often portrayed with axe or sword in hand, were armed mostly with spears,[15] as were their Anglo-Saxon, Irish, or continental contemporaries.

Infantry

Broadly speaking, spears were either designed to be used in melee, or to be thrown. Within this simple classification, there was a remarkable range of types. For example, M.J. Swanton identified thirty different spearhead categories and sub-categories in Early Saxon England.[16] Most medieval spearheads were generally leaf-shaped. Notable types of Early medieval spears include the angon, a throwing spear with a long head similar to the Roman pilum, used by the Franks and Anglo-Saxons and the winged (or lugged) spear, which had two prominent wings at the base of the spearhead, either to prevent the spear penetrating too far into an enemy or to aid in spear fencing.[17] Originally a Frankish weapon, the winged spear also was popular with the Vikings.[18] It would become the ancestor of later medieval polearms, such as the partisan and spetum.

The thrusting spear also has the advantage of reach, being considerably longer than other weapon types. Exact spear lengths are hard to deduce as few spear shafts survive archaeologically but 6 ft. – 8 ft. (1.8m – 2.5m) would seem to have been the norm. Some nations were noted for their long spears, including the Scots and the Flemish. Spears usually were used in tightly ordered formations, such as the shieldwall or the schiltron. To resist cavalry, spear shafts could be planted against the ground.[19] William Wallace drew up his schiltrons in a circle at the Battle of Falkirk in 1298 to deter charging cavalry,[20] it was a widespread tactic sometimes known as the "crown" formation.[21]

Throwing spears became rarer as the Middle Ages drew on, but survived in the hands of specialists such as the Catalan Almogavars.[22] They were commonly used in Ireland until the end of the 16th century.[23]

Spears began to lose fashion among the infantry during the 14th century, being replaced by pole weapons that combined the thrusting properties of the spear with the cutting properties of the axe, such as the halberd. Where spears were retained they grew in length, eventually evolving into pikes, which would be a dominant infantry weapon in the 16th and 17th centuries.[24]

Cavalry

Cavalry spears were originally the same as infantry spears and were often used with two hands or held with one hand overhead. In the 11th century, after the adoption of stirrups and a high-cantled saddle, the spear became a decidedly more powerful weapon. A mounted knight would secure the lance by holding it with one hand and tucking it under the armpit (the couched lance technique)[25] This allowed all the momentum of the horse and knight to be focused on the weapon's tip, whilst still retaining accuracy and control. This use of the spear spurred the development of the lance as a distinct weapon that was perfected in the medieval sport of jousting.[26]

In the 14th century, tactical developments meant that knights and men-at-arms often fought on foot. This led to the practice of shortening the lance to about 5 ft. (1.5m.) to make it more manageable.[27] As dismounting became commonplace, specialist pole weapons such as the pollaxe were adopted by knights and this practice ceased.[28]

European Renaissance and after

Infantry

The development of both the long, two-handed pike and gunpowder in Renaissance Europe saw an ever increasing focus on integrated infantry tactics.[29] Those infantry not armed with these weapons carried variations on the pole-arm, including the halberd and the bill. Ultimately, the spear proper was rendered obsolete on the battlefield. Its last flowering was the half-pike or spontoon,[30] a shortened version of the pike carried by officers and NCOs. While originally a weapon, this came to be seen more as a badge of office, or leading staff by which troops were directed.[31] The half-pike, sometimes known as a boarding pike, was also used as a weapon on board ships until the 19th century.[32]

Cavalry

At the start of the Renaissance, cavalry remained predominantly lance-armed; gendarmes with the heavy knightly lance and lighter cavalry with a variety of lighter lances. By the 1540s, however, pistol-armed cavalry called reiters were beginning to make their mark. Cavalry armed with pistols and other lighter firearms, along with a sword, had virtually replaced lance armed cavalry in Western Europe by the beginning of the 17th century,[33] although the lance persisted in Eastern Europe, from whence it was reintroduced into the European mainstream in the 19th century.

Asia

China

Spears (qiang) were used first as hunting weapons amongst the ancient Chinese. They became popular as infantry weapons during the Warring States and Qin era, when spearmen were used as especially highly disciplined soldiers in organized group attacks. When used in formation fighting, spearmen would line up their large rectangular or circular shields in a shieldwall manner. The Qin also employed long spears (more akin to a pike) in formations similar to Swiss pikemen in order to ward off cavalry. The Han Empire would use similar tactics as its Qin predecessors. Halberds, polearms, and dagger axes were also common weapons during this time.

Spears were also common weaponry for Warring States, Qin, and Han era cavalry units. During these eras, the spear would develop into a longer lance-like weapon used for cavalry charges.

India

South Asian spears were used both in missile and non-missile form, both by cavalry and foot-soldiers. Mounted spear-fighting was practiced using with a ten-foot, ball-tipped wooden lance called a bothati, the end of which was covered in dye so that hits may be confirmed. Spears were constructed from a variety of materials such as the sang made completely of steel, and the ballam which had a bamboo shaft. The Rajputs wielded a type of spear for infantrymen which had a club integrated into the spearhead, and a pointed butt end. Other spears had forked blades, several spear-points, and numerous other innovations. One particular spear unique to India was the vita or corded lance. Used by the Maratha army, it had a rope connecting the spear with the user's wrist, allowing the weapon to be thrown and pulled back.

Japan

Medieval Japan employed spears for infantrymen to use, but it was not until the 11th century in that samurai began to prefer spears over bows. Several polearms were used in the Japanese theatres; the naginata was a glaive-like weapon with a long, curved blade popularly among the samurai and the Buddhist warrior-monks, often used against cavalry; the yari was a longer polearm, with a shorter and often straight-bladed spearhead, which became the weapon of choice of both the samurai and the ashigaru (footmen) during the Warring States Era.

Korea

Spears and pole-arms were utilized heavily throughout the history of Korean warfare with some types serving specialized purposes. Especially during the Three Kingdoms of Korea period, in which wars among the Korean states, as well as with neighboring Chinese dynasties, were highly frequent, Korean military forces were constantly improving upon weaponry and martial practices. During this time period, spears were often lengthy and sturdy and were armed by heavily armored shock infantrymen, reflecting the prevalence of cavalry engagements and open combat.

The Goguryeo Empire, which was by far the most powerful Korean sovereignty of that time with its domain stretching from northern Korea to the entirety of Manchuria and parts of northeastern China, was especially well known for its highly motivated and battle-hardened soldiers. Goguryeo cavalrymen were primarily armed with spears, with swords relegated to a secondary position.

Pole-arms and spears eventually became commonplace weapons among Korean infantry during the Joseon dynasty, and military officers were expected to be proficient in the use of at least several types of spears. One of the most prolific pole weapons of this period was the dangpa, a modified type of trident. Its unique feature is the slightly crooked two outer teeth of the weapon, with a middle tip extending farther. This design was made so that the soldier could stab and penetrate deep into his enemy with maximum force, while the two outer teeth would prevent the weapon from becoming stuck to the opponent's body. Most Korean foot soldiers, especially those positioned to defend fortresses and strongholds, were highly trained in the use of the dangpa. Some other pole weapons were used such as the woldo, a weapon that resembles its more well-known cousin the Chinese Guan dao. The woldo was used mostly by Joseon warriors and officers.

In the late sixteenth century, Japanese forces under the leadership of warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi instigated an invasion on the Korean peninsula to initiate the Imjin Wars. The dangpa continued to be a favorite among Korean soldiers stationed to defend fortresses because of its versatility in siege combat. The dangpa's balanced weight allowed the soldier to achieve great striking power and its piercing capabilities were invaluable to forcing off climbing Japanese soldiers. Because of its length, Korean infantry armed with the dangpa could use it to corner multiple Japanese troops en masse. The dangpa was also used by Korean marines in Admiral Yi's naval operations, although to a less prominent extent. The tactical nature of Korean naval warfare relied upon superior firepower and maneuverability of Korean ships, and as such Korean sailors preferred using projectiles such as bows and arrows as primary weapons. However, in the case of boarding and close combat situations, a small number of Korean marines would be armed with the dangpa. These sailors acted as "pushing" infantry by being the first to board an enemy vessel during an engagement. The sailors, with their dangpa, would stave or "push" off approaching Japanese infantry until a significant number of Korean swordsmen could board the vessel.

Philippines

Filipino spears (sibat) were used as both a weapon and a tool throughout the Philippines. It also called bangkaw, sumbling or palupad in the islands of Visayas and Mindanao. Sibat are typically made from rattan, either with a sharpened tip or a head made from metal. These heads may either be single-edged, double-edged or barbed. Styles vary according to function and origin. For example, a sibat designed for fishing may not be the same as those used for hunting.

The spear was used as the primary weapon in expeditions and battles against neighbouring island kingdoms and it become famous during the 1521 Battle of Mactan, where the chieftain Lapu Lapu of Cebu fought against Spanish forces led by Ferdinand Magellan who was subsequently killed.

Vietnam

Along with the axe, the spear was the most common ancient weapon found in Vietnam. Spearheads are of various sizes and shapes, some only 12 centimetres in length and others 30 to 40 cm long. Spear shafts also vary greatly. Soldier figures on 13th-century vases show very short and slender spears used together with shields. Cavalry spears, up to 4 metres long, resemble the European lances drawn by 17th-century Westerners.

Mesoamerica

As advanced metallurgy was largely unknown in pre-Columbian America outside of Western Mexico and South America, most weapons in Meso-America were made of wood or obsidian. This didn't mean that they were less lethal, as obsidian may be sharpened to become many times sharper than steel.[34] Meso-American spears varied greatly in shape and size. While the Aztecs preferred the sword-like macuahuitl for fighting,[35] the advantage of a far-reaching thrusting weapon was recognised, and a large portion of the army would carry the tepoztopilli into battle.[36] The tepoztopilli was a pole-arm, and to judge from depictions in various Aztec codices, it was roughly the height of a man, with a broad wooden head about twice the length of the users' palm or shorter, edged with razor-sharp obsidian blades which were deeply set in grooves carved into the head, and cemented in place with bitumen or plant resin as an adhesive. The tepoztopilli was able both to thrust and slash effectively.

Throwing spears also were used extensively in Meso-American warfare, usually with the help of an atlatl.[37] Throwing spears were typically shorter and more stream-lined than the tepoztopilli, and some had obsidian edges for greater penetration.

Spears were used after the Meso-American period in various conflicts including the Latin American wars of independence and the Spanish American wars of independence. Plainsmen cavalry (known as llanos), led by José Antonio Pلez, used spears against the royalists in battles such as Battle of Las Queseras del Medio, the Toma de las Flecheras, and the Battle of Carabobo.[citation needed]

Native American

Typically, most spears made by Native Americans were created with materials surrounded by their communities. Usually, the shaft of the spears were made with a wooden stick while the head of the spear was fashioned from arrowheads, pieces of metal such as copper, or a bone that had been sharpened. Spears were a preferred weapon by many since it was inexpensive to create, could more easily be taught to others, and could be made quickly and in large quantities.

Native Americans used the Buffalo Pound method to kill buffalo, which required a hunter to dress as a buffalo and lure one into a ravine where other hunters were hiding. Once the buffalo appeared, the other hunters would kill him with spears. A variation of this technique, called the Buffalo Jump was when a runner would lead the animals towards a cliff. As the buffalo got close to the cliff, other members of the tribe would jump out from behind rocks or trees and scare the buffalo over the cliff. Other hunters would be waiting at the bottom of the cliff to spear the animal to death.[38]

Hunting

One of the earliest forms of killing prey for humans, hunting game with a spear and spear fishing continues to this day as both a means of catching food and as a cultural activity. Some of the most common prey for early humans were mega fauna such as mammoths which were hunted with various kinds of spear. One theory for the Quaternary extinction event was that most of these animals were hunted to extinction by humans with spears. Even after the invention of other hunting weapons such as the bow the spear continued to be used, either as a projectile weapon or used in the hand as was common in boar hunting.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2010) |

Types

- Barred spears: A barred spear has a crossbar beneath the blade, to prevent too deep a penetration of the spear into an animal. The bar may be forged as part of the spearhead or may be more loosely tied by means of loops below the blade. Barred spears are known from the Bronze Age, but the first historical record of their use in Europe is found in the writings of Xenophon in the 5th century BC.[39] Examples also are shown in Roman art. In the Middle Ages, a winged or lugged war-spear was developed (see above), but the later Middle Ages saw the development of specialised types, such as the boar-spear and the bear-spear.[40] The boar-spear could be used both on foot or horseback.

- Javelin

- Harpoon

- Trident

Modern revival

Spear hunting fell out of favour in most of Europe in the 18th century, but continued in Germany, enjoying a revival in the 1930s.[41] Spear hunting is still practiced in the USA.[42] Animals taken are primarily wild boar and deer, although trophy animals such as cats and big game as large as a Cape Buffalo are hunted with spears. Alligator are hunted in Florida with a type of harpoon.

Gene Morris, a former Air Force colonel lobbied to legalize spear hunting Alabama in 1992. Through Morris' actions, spear hunting was legalized in Alabama, though officials said they believed Morris was the only person to hunt with a spear in the state.[43] Morris described himself as "The Greatest Living Spear Hunter in the World." He opened a spear hunting museum in Sumerdale, Alabama. He died in 2011.

In myth and legend

Symbolism

Like many weapons, a spear may also be a symbol of power. In the Chinese martial arts community, the Chinese spear (Qiang 槍) is popularly known as the "king of weapons".

The Celts would symbolically destroy a dead warrior's spear either to prevent its use by another or as a sacrificial offering.

In classical Greek mythology Zeus' bolts of lightning may be interpreted as a symbolic spear. Some would carry that interpretation to the spear that frequently is associated with Athena, interpreting her spear as a symbolic connection to some of Zeus' power beyond the Aegis once he rose to replacing other deities in the pantheon. Athena was depicted with a spear prior to that change in myths, however. Chiron's wedding-gift to Peleus when he married the nymph Thetis in classical Greek mythology, was an ashen spear as the nature of ashwood with its straight grain made it an ideal choice of wood for a spear.

The Romans and their early enemies would force prisoners to walk underneath a 'yoke of spears', which humiliated them. The yoke would consist of three spears, two upright with a third tied between them at a height which made the prisoners stoop.[44] It has been surmised that this was because such a ritual involved the prisoners' warrior status being taken away.[citation needed] Alternatively, it has been suggested that the arrangement has a magical origin, a way to trap evil spirits.[45] The word subjugate has its origins in this practice (from Latin sub = under, jugum=a yoke).[4]

In Norse Mythology, the God Odin's spear (named Gungnir) was made by the sons of Ivaldi. It had the special property that it never missed its mark. During the War with the Vanir, Odin symbolically threw Gungnir into the Vanir host. This practice of symbolically casting a spear into the enemy ranks at the start of a fight was sometimes used in historic clashes, to seek Odin's support in the coming battle.[46] In Wagner's opera Siegfried, the haft of Gungnir is said to be from the "World-Tree" Yggdrasil.[47]

Other spears of religious significance are the Holy Lance[48] and the Lúin of Celtchar,[49] believed by some to have vast mystical powers.

Sir James George Frazer in The Golden Bough[50] noted the phallic nature of the spear and suggested that in the Arthurian Legends the spear or lance functioned as a symbol of male fertility, paired with the Grail (as a symbol of female fertility).

Tamil (Thamizh) people worship the spear as the weapon of the god Murugan. Murugan's spear is called the Vel. In Sri Lanka and India there is a dominant caste named Vellalar. The name Vellalar is derived from Vel and Alar, which means "ruler of the spear".

The term spear is also used (in a somewhat archaic manner) to describe the male line of a family, as opposed to the distaff or female line.

Legends

- Amenonuhoko, spear of Izanagi and Izanami, creator gods in Japanese mythology

- Gáe Bulg, spear of Cúchulainn, hero in Irish mythology

- Gáe Buide and Gáe Derg, spears of Diarmuid Ua Duibhne which could inflict wounds that none can recover from

- Green Dragon Crescent Blade, a guan dao wielded by General Guan Yu in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms

- Gungnir, spear of Odin, a god in Norse mythology

- Holy Lance, said to be the spear that pierced the side of Jesus

- Octane Serpent Spear of Zhang Fei (Yide) from the Three Kingdoms period in China

- Spear of Fuchai, the spear used by Goujian's arch-rival, King Fuchai of Wu, in China

- Spear of Lugh, named after Lugh, a god in Irish mythology

- Trident, a three-pronged fishing spear associated with a number of water deities, including the Etruscan Nethuns, Greek Poseidon, and Roman Neptune.

- Trishula, a three-pronged spear wielded by the Hindu deities Durga and Shiva

- Rhongomyniad, or simply 'Ron,' the spear of King Arthur according to British tradition.[51]

- Vasavi Shakti, spear of the Indian thunder god Indra, and given to the hero Karna in the Marabharata

See also

Notes and references

- ^ Weir, William. 50 Weapons That Changed Warfare. The Career Press, 2005, p 12.

- ^ Jill D. Pruetz1 and Paco Bertolani, Savanna Chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes verus, Hunt with Tools", Current Biology, March 6, 2007

- ^ Orangutan attempts to hunt fish with spear, April 26, 2008

- ^ Lower Palaeolithic hunting spears from Germany. Hartmut Thieme. Letters to Nature. Nature 385, 807 – 810 (27 February 1997); doi:10.1038/385807a0 [1]

- ^ Monte Morin, "Stone-tipped spear may have much earlier origin", Los Angeles Times, November 16, 2012

- ^ Rick Weiss, "Chimps Observed Making Their Own Weapons", The Washington Post, February 22, 2007

- ^ Wymer, John (1982). The Palaeolithic Age. London: Croom Helm. p. 192. ISBN 0-7099-2710-X.

- ^ Webster, T.B.L. (1977). From Mycenae to Homer. London: Methuen. pp. 166–8. ISBN 0-416-70570-7. Retrieved 15 Feb 2010.

- ^ Hanson, Victor Davis (1999). "Chapter 2 : The Rise of the City State and the Invention of Western Warfare". The Wars of the Ancient Greeks. London: Cassell. pp. 42–83. ISBN 0-304-35982-3.

- ^ Hanson (1999), p. 59

- ^ Hanson (1999), pp.147–8

- ^ Hanson (1999), pp149-150

- ^ Hunt, Peter. The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare: Volume 1, Greece, The Hellenistic World and the Rise of Rome. Cambridge University Press, 2007, p. 108

- ^ Bishop, M.C.; Coulston J.C. (1989). Roman Military Equipment. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications. ISBN 0-7478-0005-7.

- ^ Viking Spears

- ^ Swanton, M.J. (1973). The Spearheads of the Anglo-Saxon Settlement. London: Royal Archaeological Institute.

- ^ Martin, Paul (1968). London: Herbert Jenkins. p. 226.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Viking Spears, op.cit.

- ^ e.g. at the Battle of Steppes 1213 Oman, Sir Charles (1991) [1924]. The Art of War in the Middle Ages. Vol. 1. London: Greenhill Books. p. 451. ISBN 1-85367-100-2.

- ^ Fisher, Andrew (1986). William Wallace. Edinburgh: John Donald. p. 80. ISBN 0-85976-154-1.

- ^ Verbruggen, J.F. (1997). The Art of Warfare in Western Europe in the Middle Ages (2nd. ed.). Woodbridge: Boydell Press. pp. 184–5. ISBN 0-85115-630-4.

- ^ Morris, Paul (September 2000). ""We have met Devils!" : The Almogavars of James I and Peter III of Catalonia-Aragon". Anistoriton. 004. Retrieved 2009-08-04.

- ^ Heath, Ian (1993). The Irish Wars 1485–1603. Oxford: Osprey. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-85532-280-6.

- ^ Arnold, Thomas (2001). The Renaissance at War. London: Cassel & Co. pp. 60–72. ISBN 0-304-35270-5.

- ^ Nicholson, Helen (2004). Medieval Warfare. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan. pp. 102–3. ISBN 0-333-76331-9.

- ^ * Sébastien Nadot, Rompez les lances ! Chevaliers et tournois au Moyen Age, Paris, ed. Autrement, 2010. (Couch your lances ! Knights and tournaments in the Middle Ages...)

- ^ Nicholson (2004),p. 102

- ^ Nicholson (2004), p101

- ^ Arnold (2001), pp.66–72, 78–81

- ^ Oakeshott, Ewart (1980). European Weapons and Armour. Guildford & London: Lutterworth Press. p. 56. ISBN 0-7188-2126-2.

- ^ Oakeshott (1980), p.55

- ^ Oakeshott (1980), p.56

- ^ Arnold (2001), pp.92–100

- ^ Buck, BA (March 1982). "Ancient technology in contemporary surgery". The Western journal of medicine. 136 (3): 265–269. ISSN 0093-0415. OCLC 115633208. PMC 1273673. PMID 7046256.

- ^ http://www.precolumbianweapons.com/warfare.htm

- ^ http://www.precolumbianweapons.com/spears.htm

- ^ http://www.precolumbianweapons.com/atlatl.htm

- ^ "Native American Spears". Indians.org. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ Blackmore, Howard (2003). Hunting Weapons from the Middle Ages to the Twentieth Century. Dover. pp. 83–4. ISBN 0-486-40961-9. Retrieved March 2010.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Blackmore (2003), pp.88–91

- ^ Blackmore (2003), pp92-3.

- ^ Hunting With Spears

- ^ http://www.aonmag.com/article.php?id=3016&cid=158

- ^ Connolly, Peter (1981). Greece and Rome at War. London: Macdonald Phoebus. p. 89. ISBN 0-356-06798-X.

- ^ M. Cary and A. D. Nock : Magic Spears, The Classical Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 3/4 (Jun. – Oct., 1927), pp. 122–127

- ^ Crossley-Holland, Kevin (1982). The Norse Myths. London: Penguin. pp. 51, 197. ISBN 0-14-006056-1.

- ^ Siegfried, Act I, Scene 2

- ^ "Lance, Holy" The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Ed. E. A. Livingstone. Oxford University Press, 2006. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. [2]

- ^ "Lúin" A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. James McKillop. Oxford University Press, 1998. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. [3]

- ^ Frazer, James G. : The Golden Bough, 1890

- ^ P. K. Ford, "On the Significance of some Arthurian Names in Welsh" in Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies 30 (1983), pp.268–73 at p.71; R. Bromwich and D. Simon Evans, Culhwch and Olwen. An Edition and Study of the Oldest Arthurian Tale (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1992), pp.64

External links

Historical

- SPEAR (O. Eng. spere, O. H. Ger. sper, mod. Ger. sp)

- Anglo-Saxon spear forging

- Ancient Weapons – Spears

- Viking Spears

- Irish Living History site

- Masai Spears

- The Vel in Sri lanka