Stećak

| Stećak | |

|---|---|

Stećak in Radimlja necropolis | |

| Official name | Stećci Medieval Tombstones Graveyards |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, vi |

| Designated | 2016 (40th session) |

| Reference no. | 1504 |

| State Party | |

| Region | Europe and North America |

Stećak ([stetɕak]; plural: Stećci [stetɕtsi]) is the name for monumental medieval tombstones that lie scattered across Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the border parts of Croatia, Montenegro and Serbia. An estimated 60,000 are found within the borders of modern Bosnia and Herzegovina and the rest of 10,000 are found in what are today Croatia (4,400), Montenegro (3,500), and Serbia (4,100), at more than 3,300 odd sites with over 90% in poor condition.[1][2]

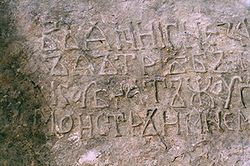

Appearing in the mid 12th century, with the first phase in the 13th century, the tombstones reached their peak in the 14th and 15th century, before disappearing during the Ottoman occupation in the very early 16th century.[1] They were a common tradition amongst Bosnian Church, Catholic / Orthodox Church but some argue the Bosnian Bogumil's followers alike.[3] By the scholars are mostly related to the autochthonous Vlachian population. The epitaphs on them are mostly written in extinct Bosnian Cyrillic alphabet. The one of largest collection of these tombstones is named Radimlja, west of Stolac in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[2]

Stećaks was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2016. It includes 30 necropolis – of which 22 from Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2 from Croatia, 3 from Montenegro, and 3 from Serbia.[1]

Etymology

The word itself is a contracted form of the older word stojećak, which is derived from the South Slavic verb stajati (engl. stand). It literally means the "tall, standing thing".[4] Sometime also called as mašeti (Italian for rock, or Turkish for tombstone of a fallen hero), mramorovi (marble), usadjenik (implantation), on the stećak inscriptions they are called as bilig (mark), kamen bilig (stone mark), kâm/kamen (stone), hram (shrine), zlamen/kuća (house), raka (pit), greb/grob (grave).[4][5] Although in Bosnia and Herzegovina under the name stećak among the people meant high monolithic standing stones (i.e. sanduk and sljemenjak form), in 20th century the word stećak was accepted in science as general term, including for plate gravestones.[6]

Characteristics

Definition

They are characteristic for the territory of present-day Hercegovina, central Bosnia, Podrinje and Dalmatia (especially South of river Cetina), and some minor parts of Montenegro, Kosovo and Western Serbia, Posavina and Northwestern Bosnia.[7]

Stećaks are described as stone, monolithic, horizontal and vertical tombstones prismatic shape with flat or gable-top surface, with or without pedestal.[8][7] The chronology established by Marian Wenzel considers stećaks developed from the plate headstones with the oldest from 1220 (probably first somewhere in the mid-12th century[1]), monumental emerged somewhere in 1360, those with visual representations around 1435-1477, and that total production of stećaks ended in 1505.[9][10] Stećaks in the form of chest (sanduk) and ridge/saddle-roofed (sljemenjak) do not appear before the middle or the end of the 14th century, while the remaining two basic forms - the upright pole and cross, no more than half of the 15th century. In the latter "upright" forms can be seen influence of the nišan - the upright monolithic stones on top of the Muslim (Turkish) graves, which emerge already in the end of 14th century in conquered parts of Macedonia and Serbia.[7] The majority of stećaks are not or are very simply decorated.[4]

In the example of Bosnia and Herzegovina according to UNESCO there's "about 40,000 chests, 13,000 slabs, 5,500 gabled tombstones, 2,500 pillars/obelisks, 300 cruciform tombstones and about 300 tombstones of indeterminate shape have been identified. Of these, more than 5,000 bear carved decorations".[5]

The initial stage of stećaks developing which included simple recumbent plates or slabs isn't specific for the region, yet it is of broad West Mediterranean origin, and as such the term stećak (implying the chest and ridge form) is misleading for all tombstone forms. The slabs type of burial was a typical kind of burial of the West Mediterranean world in the 14-15th century, but which had special method of production and ornamentation in the Balkan, customized according to the stonemasonry skills and microenvironment.[11][12]

Decorations

"I have for long lain here, and for much longer shall I lie"; "I was born into a great joy and I died into a great sorrow"; "I was nothing then, I am nothing now"; "May he who topples this stone be cursed"

— Some translated examples of inscriptions.[4]

A fraction of stećaks bear inscriptions, mostly in extinct Bosnian Cyrillic, some in Glagolitic and Latin script. They are mostly brazen reminders of wisdom and mortality, relay a dread of death, more anxiety than peace.[4]

Their most remarkable feature is their decorative motifs, many of which remain enigmatic to this day; spirals, arcades, rosettes, vine leaves and grapes, lilium, stars (often six-pointed) and crescent moons are among the images that appear. Figural motifs include processions of deer, horse, dancing the kolo, hunting, chivalric tournaments, and, most famously, the image of the man with his right hand raised, perhaps in a gesture of fealty.[10][4]

A series of visual representations on the tombstones can not be simplistically interpreted as real scenes from the life. The shield on the tombstones, usually with the crossbar, crescent and star, cannot be coat of arms, neither the lilium which is stylized is used in the heraldic sense. On one stećak is displayed tied leopard and above him winged dragon. Already in 1979, historian Hadžijahić noted that the horsemen are not riding with reins, yet (if are not "hunting") their hands are free and pointed to the sky, implying possible cult significance.[13] In 1985, Maja Miletić noted the simbolic and religious character of the stećak scenes.[14] All the "life scenes" are considered to be part of ceremonial.[15] Several scholars concluded that the motifs show the continuity of old Balkan pre-Christian symbolism from the autochthonous Illyrians tribes and prehistoric time.[16] Benac noted that the displays of sole horse with snake, as well sole deer with bird, simbolize the soul of the deceased going to other world, which representations are resembling to those found on Iapydes artefacts.[17] The Illyrian god Medaurus is described as riding on horseback and carrying a lance.[18]

Of the all animals deer is the most represented, and mostly is found on stećaks in Herzegovina.[19] According to Dragoslav Srejović, spread of Christianity didn't cause disappearance of old cult and belief in sacred deer.[20] Historian Šefik Bešlagić synthesized the representations of deer: sometime accompanied by a bird (often on the back or horns), cross or lilium, frequently are shown series of deer or doe, as well with a bow and arrow, dog and hunter(s) with a spear or sword (often on a horse). It is displayed in hunting scenes, as well some kolo processions which are led by a man who is riding a deer.[21] There scenes where deers calmly approach the hunter, or deers with enormous size and sparse horns.[14] Most of the depictions of "deer hunting" on the stećaks are facing the West, which had the symbolic meaning for death and other world. In the numerous hunting scenes of stećaks in only one deer is wounded (the stećak has some anomalies), indicating unrealistic meaning. In the Roman and Parthian-Sasanian art hunted animals are mortally wounded, and deer is only one of many, while on stećaks is the only hunted animal.[22]

The motifs of kolo procession along a deer, and its specific direction of dancing, although not always easily identifiable, show its a mortal dance compared to cheerful dance. From Iapydes urns, up to present day women in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro, remorseful dances are played in the western direction toward sunset. In Eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina so-called Ljeljenovo kolo,[nb 1] with ljeljen local name for jelen (deer) implying jelenovo kolo, is danced by making the gate of the raised hand and ringleader of these gates tries to pull all kolo dancers through them until the kolo is entangled, after that, playing in the opposite direction, until the kolo is unraveled. Its origin is in mortuary ritual guiding the soul to another world and the meaning of renewal of life.[15]

The vast regional, but scarce (usually only one) in-graveyard distribution mostly in the center or some notable position of cross-type stećaks (križine), and their almost exclusively ornament of the crescent Moon and stars, indicate cemetery label for specific (pagan) religious affiliation according to the archeologist Ante Milošević. The simbolism of the Moon and stars (Sun), which are often found on stećaks, could be traced to Mithraism which had old Mazdakism belief that the dead body goes to the Moon, while souls to the Sun.[25]

Schools

They were carved by kovač/klesar (smith, mason), while the inscriptions, probably as a template, were compiled by dijak/pisar (pupil, scribe), both most possibly introduced with archaic symbolism. Stećaks in Bosnia and Herzegovina can be divided on two "stonemasonry school"; Herzegovian (sarcophagi with arcades, figurative scenes, a wealth of motifs), and East Bosnian (sarcophagi in the form of chalets, floral motives).[26]

Local characteristic of stećaks in the territory around Cetina river is their rare ornateness, of which only 8-10% have simple decoration.[27][28] Those from upper Cetina are smaller and by type and style relate to those from Knin and Livno, while those from mid Cetina are more monumental.[29] Specific plate stećaks were found in village Bitelić which are decorated with identical geometric ornament, not found in Dalmatia nor Bosnia and Herzegovina, however by the nature of ornament and surface treatment is considered possible connection with several monuments near Church of St. Peter in Nikšić, Montenegro.[27][30]

History and origin

There different and still inconclusive theories on the religious and ethnic affiliation of the stećaks.[31]

Religion

Since the mid of 19th century many historians, including Alexander Soloviev, Alojz Benac, Nada Miletić and Šefik Bešlagić, have argued that the stećaks were related to the origin of the Bosnian Church i.e. Bogomils or other dualist groups.[31][10][32] Others have asserted that the church was actually founded by Franciscan monks from the Catholic Church.[33] However, Benac noted that stećaks were not built in First Bulgarian Empire, and that in Central Bosnia where were centers of Bosnian Kingdom and Church is smaller stećaks concentration, as well higher number of stećaks of poor design, but also older date.[34]

Whatever the Bosnian Church origin, Marian Wenzel, the world's once leading authority on the art and artifacts of medieval Bosnia and Herzegovina,[35] concluded that the stećaks tombstones were a common tradition amongst Catholic, Orthodox and Bosnian Church followers alike.[3] Wenzel's conclusion supported other historians' claims that the stećaks reflect a regional cultural phenomenon rather than belonging to a particular religious faith.[32][36]

Christian Gottlob Wilke sought origins of the simbolic motifs in the old Mediterranean spirituali and religious concepts. Đuro Basler in the artistic expression saw some parallels in late Romanesque art, while in simbolic motifs three components; pre-Christian, Christian and Manichaean (i.e. Bogomils).[31]

Ethnic origin

The ethnic identity of the stećaks has not yet been fully clarified. Until now the most dominant, but still not fully accepted,[34] theory relates them with the autochthonous Vlachian communities in the Balkan.[10] Some other scholars proposed unconvincing and rejected theories; Dominik Mandić considered them to be part of the ritual of burial by the pagan Croats from the Red Croatia, while Vladislav Skarić considered they have represented Old Slavic "eternal home", and that initially were built from wood.[31] Vladimir Ćorović pointed out that the "Old Slavs have not used monoliths or larger blocks of stone to make their apartments, let alone for the grave signs. Even the less for their writing or decorations".[19]

Vlachs

The autochthonous Vlachian theory was proposed by Bogumil Hrabak (1956) and Marian Wenzel (1962), and more recently was supported by the archeological and anthropological researches of skeleton remains from the graves under stećaks.[37] However, the theory is much older and was first proposed by Arthur Evans in his work Antiquarian Researches in Illyricum (1883). While doing research with Felix von Luschan on stećak graves around Konavle found out that a large number of skulls weren't of Slavic origin yet similar to older Illyrian and Arbanasi tribes, as well noted that Dubrovnik memorials recorded those parts to be inhabited by the Vlachs until 15th century.[6]

Hrabak was the first scholar to connect the historical documents and their relation to the persons mentioned on rare inscriptions on the stećaks. In 1953 concluded that the smith-stonemason Grubač from Boljun necropolis near Stolac built stećak of Bogavac Tarah Bol(j)unović not later than 1477, and that most of the monuments of Herzegovinian Vlachs, and not only Herzegovian and not only Vlachs,[4] could be dated to the second half of the 15th century.[6] Wenzel in one of her studies researched sixteen stećaks with similar dating and historically known persons. She noted the possibility that initially the stone monuments as such could have been introduced by the feudal nobility in the mid 14th century, which tradition was embraced by the Vlach tribes who introduced figural decoration.[6][4] The termination of the stećaks production Wenzel related to the Ottoman invasion and new social circumstances, with the transition of Vlachs and near Slavs to Islam resulting with loss of tribal organization and characteristics of specific ethnic identity.[37][10]

Benac concluded that the distribution of the stećaks in the lands right of the Cetina river coast in the parts of Dalmatian Zagora, while their absence in the lands left of the river (with graveyards along Early Middle Age churches), show these tombstones in those parts belonged to the Vlachian communities.[7] The triangle between Šibenik, Trogir and Knin, as well surroundings of Vrlika and Trilj, which were the main centers of Vlachs have the most number of stećaks in Dalmatia.[38] In 1982, Benac noted that the highest concentration of stećaks is in South Herzegovina (territory of Trebinje, Bileća, Ljubinj and Stolac), where was high concentration of Vlachian population. Some of the stećaks inscriptions (by anthroponyms) clearly relates to some Vlachian chieftains; Tarah Boljunović from Boljun-Stolac, Vukosav Vlaćević from Vlahovići-Lubinje, Hrabreni and Miloradović in Radimlja-Stolac, and to such chieftains belong finest stećaks.[39]

The occurrence of stećaks in the Cetina county is related to the Nelipić noble family efforts to return economic and political power to whom was confiscated Knin in 1345 by king Louis I of Hungary in exchange for Sinj and Cetina county. They thrived with the support from the Vlachs, who for the service were rewarded with benefits and common Vlach law.[27] After many conflicts and death of last noble Nelipić, then Ivan Frankopan, Vlachs supported Stjepan Vukčić Kosača.[40] The ridge stećaks of Dalmatian type can be found only in regions of Dalmatia and Southwestern Bosnia, parts ruled by the Kosača noble family. It was in his interest to settle militant and well organized Vlachs in the most risky part of his realm, to defend from Talovac forces in Cetina and Venice forces in Poljica and the coast. Thus Dalmatian type is found only West and South of Kosača capital Imotski, and later also North after fall of Bosnia.[41]

Anthropological research in 1982 on skeletons from 108 stećak graves (13-14th century) from Raška Gora near Mostar, as well some from Grborezi near Livno, shown homogeneity of the serials with clean Dinaric anthropological type, without other admixtures, indicating non-Slavic origin, yet autochthonous Vlachian population.[39] The research of 11 skeletons from necropolis at Pavlovac near Prača, often attributed to the Pavlović noble family, also shown clean Dinaric type, indicating Vlachian origin, although historical sources don't call Pavlovići as Vlachs.[12] The anthropological research in 1991 on the 40 skeletons from 28 burials (dated 1440-1450s) beneath stećaks at plateau Poljanice near the village of Bisko showed that the vast majority of the population belonged to the autochthonous Dinaric type, concluding they were anthropologically of non-Slavic origin.[10] 21 skeleton belonged to child burial, while of 19 adult burials 13 belonged to males.[42] The quarry for stećaks was found in the Northwestern part of the plateau, with one ridge as semi-finished work without any ornament.[43]

Bešlagić asserted that the Vlachs and others who have raised and decorated stećaks were not completely Christianised is confirmed with the old custom of putting attachments with the dead, with many artfeacts made of metals, textiles, ceramics and skin, coins, earrings of silver, gilded silver and solid gold which have been found in graves beneath stećaks.[44] The custom of placing drinking vessel near graves and heads is from antique time.[44]

Archeologically, some Middle Age burials from Cetina county have local specifics by which Cetina county differs from other parts of Dalmatia. In the county the burials weren't done in the ground without additional stone architecture. Some scholars related this phenomenon to the specific ethnic identity, however due to still groundbreaking research for now is considered only regional and narrow local occurrence.[42]

Financial possibilities of ordering such expensive ways of burial among Vlachs are supported and confirmed in the historical documents, with an example of Vlach from Cetina, Ostoja Bogović, who in 1377 paid the cost of burial of Vlach Priboja Papalić for 40 libra. At the time burial in Split costed 4-8 libra, while for a sum of 40 libra could be bought family grave in the church of Franciscan order in Šibenik.[45][30]

Notable Stećaks

- The oldest stećak is that of Grdeša, a 12th-century župan of Trebinje.

- The medieval Mramorje necropolis in Serbia, Monument of Culture of Exceptional Importance contains large number of Stećak tombs.[46]

- Vlatko Vuković Kosača's grave lies marked near the village of Boljuni near Stolac, Bosnia and Herzegovina, from late 14th century. The inscription on the grave was written in Bosnian Cyrillic in Ikavian accent.[47]

- The two ridge stećaks which belonged to Vlach Jerko Kustražić and his wife Vladna from the mid 15th century, in Cista near Imotski, and Split, Croatia[48]

- The ridge stećak of Vlkoj Bogdanić (son of Radmil) who died in battle in the mid 15th century, made by mason Jurina, in Lovreć, Croatia[48]

- The decorated stećak from Zgošća near Kakanj in Bosnia and Herzegovina, from 15th century. Although it has no engraved writing, since it was immaculately decorated, it is suggested that it belonged to Ban Stjepan II Kotromanić.

- Some of the best preserved stećaks can be found in area of Srebrenica municipality, in this place there are around 800 stećaks.

Today many Stećaks are also displayed in the garden of the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo.

Legacy

Alberto Fortis in the Romanticist spirit of the time described the tombstones in Cetina as warrior graves of the giants.[49]

Since 19th century stećaks are seen as a symbol of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[32] However, they were also objects of South Slavic modern ideological ethno-national myths and ownership.[4]

Gallery

-

Radimlja necropolis, Bosnia and Herzegovina

-

Radimlja, Bosnia and Herzegovina

-

Umoljani, Bosnia and Herzegovina

-

Dugopolje, Bosnia and Herzegovina

-

Risovac, Bosnia and Herzegovina

-

Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

-

Neum, Bosnia and Herzegovina

-

Velimlje, Montenegro

-

Cetinje, Montenegro

-

Klenak, Montenegro

-

Mramorje, Serbia

-

Somewhere in Dalmatia, Croatia

-

Somewhere in Dalmatia, Croatia

-

Imotski, Croatia

Notes

- ^ see Spring procession of Ljelje/Kraljice in Croatia with swords and flowers, similarly danced by Vlachs east of Beograd at the day of Pentecost.[15] The etymological and cultural relation of jelen (deer), Ljelja and Ljeljo which are children of Perun, as well flower ljiljan (lilium) also called as perunika is still to be confirmed.[23] Ivo Pilar noted that the use of name Ljeljen for hills in toponymy of Herzegovina and Eastern Bosnia is common.[24]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d "Joint Nomination for Inclusion of Stećci - Medieval Tombstones in the World Heritage List". UNESCO. 14 April 2014.

- ^ a b Musli, Emir (23 November 2014). "Čiji su naši stećci?" (in Bosnian). Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ^ a b Walasek, Helen (2002). "Marian Wenzel 18 December 1932 - 6 January 2002". Bosnian Institute.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Buturovic 2016.

- ^ a b "Stećaks - Mediaeval Tombstones (Bosnia and Herzegovina)". UNESCO. 18 April 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d Mužić 2009, p. 322.

- ^ a b c d Cebotarev 1996, p. 321.

- ^ Milošević 1991, p. 6, 61.

- ^ Milošević 1991, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f Cebotarev 1996, p. 322.

- ^ Milošević 1991, p. 6–7.

- ^ a b Mužić 2009, p. 326.

- ^ Mužić 2009, p. 328.

- ^ a b Mužić 2009, p. 329.

- ^ a b c Mužić 2009, p. 334.

- ^ Mužić 2009, p. 329–335.

- ^ Mužić 2009, p. 332–333.

- ^ Mužić 2009, p. 333.

- ^ a b Mužić 2009, p. 332.

- ^ Mužić 2009, p. 331.

- ^ Mužić 2009, p. 328–329.

- ^ Mužić 2009, p. 336.

- ^ Mužić 2009, p. 335.

- ^ Mužić 2009, p. 331–332.

- ^ Milošević 1991, p. 42.

- ^ Mužić 2009, p. 327, 336.

- ^ a b c Milošević 1991, p. 40.

- ^ Milošević 2013, p. 91.

- ^ Milošević 1991, p. 61.

- ^ a b Cebotarev 1996, p. 323.

- ^ a b c d Milošević 1991, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Ronelle Alexander; Ellen Elias-Bursac (2010). Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, a Textbook: With Exercises and Basic Grammar. University of Wisconsin Pres. p. 270. ISBN 9780299236540.

- ^ Fine, John V. A. (2007). The Bosnian Church: Its Place in State and Society from the Thirteenth to the Fifteenth Century: A New Interpretation. London: SAQI, The Bosnian Institute. ISBN 0-86356-503-4.

- ^ a b Mužić 2009, p. 327.

- ^ Brook, Anthea (March 5, 2002). "Marian Wenzel". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- ^ Fine, John V. A. (1991). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. p. 486. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- ^ a b Milošević 1991, p. 8.

- ^ Milošević 2013, p. 90.

- ^ a b Mužić 2009, p. 323.

- ^ Milošević 1991, p. 52–53.

- ^ Milošević 1991, p. 54.

- ^ a b Milošević 1991, p. 35.

- ^ Milošević 1991, p. 37.

- ^ a b Mužić 2009, p. 338.

- ^ Milošević 1991, p. 45.

- ^ a b Monuments of Culture in Serbia: "Некропола стећака" (SANU) (in Serbian and English)

- ^ Šimić, Marinka. "JEZIK BOLJUNSKIH NATPISA" (PDF). Staroslavenski institut.

- ^ a b Milošević 1991, p. 54, 62.

- ^ Milošević 1991, p. 39.

- Sources

- Milošević, Ante (1991). Stećci i Vlasi: Stećci i vlaške migracije 14. i 15. stoljeća u Dalmaciji i jugozapadnoj Bosni [Stećaks (Standing Tombstones) and Migrations of the Vlasi (Autochthonous Population) in Dalmatia and Southwestern Bosnia in the 14th and 15th Centuries] (in Croatian). Split: Regionalni zavod za zaštitu spomenika kulture.

- Cebotarev, Andrej (1996). "Review of Stećaks (Standing Tombstones) and Migrations of the Vlasi (Autochthonous Population) in Dalmatia and Southwestern Bosnia in the 14th and 15th Centuries". Povijesni prilozi [Historical Contributions] (in Croatian). 14 (14). Zagreb: Croatian Institute of History.

- Milošević, Ante (2004). "Stećci - chi li fece e quando?" [Stećaks - who made them and when?]. Hortus Artium Medievalium (in Italian). 10. Zagreb: International Research Center for Late Antiquity and Middle Ages.

- Mužić, Ivan (2009). "Vlasi i starobalkanska pretkršćanska simbolika jelena na stećcima". Starohrvatska prosvjeta (in Croatian). III (36). Split: Museum of Croatian Archaeological Monuments: 315–349.

- Lovrenović, Dubravko (2013). Stećci: Bosansko i humsko mramorje srednjeg vijeka [Stećci: Bosnian and Hum marbles from Middle Age] (in Croatian). Ljevak. ISBN 9789533035468.

- Milošević, Ante (2013). "O problematici stećaka iz dalmatinske perspektive" [About the issue of Stećci from the Dalmatian perspective]. Godišnjak (in Croatian). 42. Sarajevo: Academy of Sciences and Arts of Bosnia and Herzegovina: 89–102. ISSN 2232-7770.

- Buturovic, Amila (2016). Carved in Stone, Etched in Memory: Death, Tombstones and Commemoration in Bosnian Islam since c.1500. Routledge. ISBN 9781317169567.

External links

- Croatian Encyclopaedia (2011). "Stećci".

- Burial monuments and structures

- Medieval Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Medieval Croatia

- Medieval Serbia

- Medieval Montenegro

- Medieval European sculptures

- Rock art in Europe

- Rock art in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- World Heritage Site Tentative list

- World Heritage Sites in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- World Heritage Sites in Croatia

- World Heritage Sites in Montenegro

- World Heritage Sites in Serbia