The Well-Tempered Clavier

The Well-Tempered Clavier, BWV 846–893, is a collection of two series of Preludes and Fugues in all major and minor keys, composed for solo keyboard by Johann Sebastian Bach. In the German of Bach's time Clavier (keyboard) was a generic name indicating a variety of keyboard instruments, most typically a harpsichord or clavichord – but not excluding an organ either.

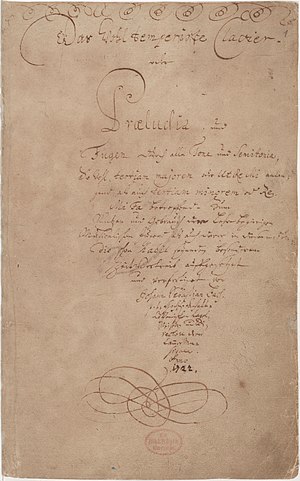

The modern German spelling for the collection is Das wohltemperierte Klavier (WTK). Bach gave the title Das Wohltemperirte Clavier to a book of preludes and fugues in all 24 major and minor keys, dated 1722, composed "for the profit and use of musical youth desirous of learning, and especially for the pastime of those already skilled in this study". Some 20 years later Bach compiled a second book of the same kind, which became known as The Well-Tempered Clavier, Part Two (in German: Zweyter Theil, modern spelling: Zweiter Teil).

Modern editions usually refer to both parts as The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I (WTC I) and The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book II (WTC II), respectively.[1] The collection is generally regarded as being among the most influential works in the history of Western classical music.[citation needed]

Composition history

Each set contains twenty-four pairs of preludes and fugues. The first pair is in C major, the second in C minor, the third in C-sharp major, the fourth in C-sharp minor, and so on. The rising chromatic pattern continues until every key has been represented, finishing with a B-minor fugue. The first set was compiled in 1722 during Bach's appointment in Köthen; the second followed 20 years later in 1742 while he was in Leipzig.

Bach recycled some of the preludes and fugues from earlier sources: the 1720 Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, for instance, contains versions of eleven of the preludes of the first book of the Well-Tempered Clavier. The C-sharp major prelude and fugue in book one was originally in C major – Bach added a key signature of seven sharps and adjusted some accidentals to convert it to the required key.

In Bach's own time no similar collections were published, except one by Johann Christian Schickhardt (1681–1762), whose Op. 30 L'alphabet de la musique, contained 24 sonatas for recorder/flute/violin, in all keys.[2]

Precursors

Although the Well-Tempered Clavier was the first collection of fully worked keyboard pieces in all 24 keys, similar ideas had occurred earlier. Before the advent of modern tonality in the late 17th century, numerous composers produced collections of pieces in all seven modes: Johann Pachelbel's magnificat fugues (composed 1695–1706), Georg Muffat's Apparatus Musico-organisticus of 1690 and Johann Speth's Ars magna of 1693 for example. Furthermore, some two hundred years before Bach's time, equal temperament was realized on plucked string instruments, such as the lute and the theorbo, resulting in several collections of pieces in all keys (although the music was not yet tonal in the modern sense of the word):

- a cycle of 24 passamezzo–saltarello pairs (1567) by Giacomo Gorzanis (c.1520–c.1577)[3]

- 24 groups of dances, "clearly related to 12 major and 12 minor keys" (1584) by Vincenzo Galilei (c.1528–1591)[4]

- 30 preludes for 12-course lute or theorbo by John Wilson (1595–1674)[5][6]

One of the earliest keyboard composers to realize a collection of organ pieces in successive keys was Daniel Croner (1656–1740), who compiled one such cycle of preludes in 1682.[7][8] His contemporary Johann Heinrich Kittel (1652–1682) also composed a cycle of 12 organ preludes in successive keys.[9]

Ariadne musica neo-organoedum, by J.C.F. Fischer (1656–1746) was published in 1702 and reissued 1715. It is a set of 20 prelude-fugue pairs in ten major and nine minor keys and the Phrygian mode, plus five chorale-based ricercars. Bach knew the collection and borrowed some of the themes from Fischer for the Well-Tempered Clavier.[10] Other contemporary works include the treatise Exemplarische Organisten-Probe (1719) by Johann Mattheson (1681–1764), which included 48 figured bass exercises in all keys,[11] Partien auf das Clavier (1718) by Christoph Graupner (1683–1760) with eight suites in successive keys,[12] and Friedrich Suppig's Fantasia from Labyrinthus Musicus (1722), a long and formulaic sectional composition ranging through all 24 keys which was intended for an enharmonic keyboard with 31 notes per octave and pure major thirds.[11][13] Finally, a lost collection by Johann Pachelbel (1653–1706), Fugen und Praeambuln über die gewöhnlichsten Tonos figuratos (announced 1704), may have included prelude-fugue pairs in all keys or modes.[14]

It was long believed that Bach had taken the title The Well-Tempered Clavier from a similarly-named set of 24 Preludes and Fugues in all the keys, for which a manuscript dated 1689 was found in the library of the Brussels Conservatoire. It was later shown that this was the work of a composer who was not even born in 1689: Bernhard Christian Weber (1 December 1712 – 5 February 1758). It was in fact written in 1745–50, and in imitation of Bach's example.[15][16]

Well-Tempered tuning

Bach's title suggests that he had written for a (12-note) well-tempered tuning system in which all keys sounded in tune (also known as "circular temperament"). The opposing system in Bach's day was meantone temperament[citation needed] in which keys with many accidentals sound out of tune. (See also musical tuning.) Bach would have been familiar with different tuning systems, and in particular as an organist would have played instruments tuned to a meantone system.

It is sometimes assumed that by "well-tempered" Bach intended equal temperament, the standard modern keyboard tuning which became popular after Bach's death, but modern scholars suggest instead a form of well temperament.[17] There is debate whether Bach meant a range of similar temperaments, perhaps even altered slightly in practice from piece to piece, or a single specific "well-tempered" solution for all purposes.

Intended tuning

During much of the 20th century it was assumed that Bach wanted equal temperament, which had been described by theorists and musicians for at least a century before Bach's birth. Internal evidence for this may be seen in the fact that in Book 1 Bach paired the E-flat minor prelude (6 flats) with its enharmonic key of D-sharp minor (6 sharps) for the fugue. This represents an equation of the most tonally remote enharmonic keys where the flat and sharp arms of the circle of fifths cross each other opposite to C major. Any performance of this pair would have required both of these enharmonic keys to sound identically tuned, thus implying equal temperament in the one pair, as the entire work implies as a whole. However, research has continued into various unequal systems contemporary with Bach's career. Accounts of Bach's own tuning practice are few and inexact. The three most cited sources are Forkel, Bach's first biographer; Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg, who received information from Bach's sons and pupils; and Johann Kirnberger, one of those pupils.

Forkel reports that Bach tuned his own harpsichords and clavichords and found other people's tunings unsatisfactory; his own allowed him to play in all keys and to modulate into distant keys almost without the listeners noticing it. Marpurg and Kirnberger, in the course of a heated debate, appear to agree that Bach required all the major thirds to be sharper than pure—which is in any case virtually a prerequisite for any temperament to be good in all keys.[18]

Johann Georg Neidhardt, writing in 1724 and 1732, described a range of unequal and near-equal temperaments (as well as equal temperament itself), which can be successfully used to perform some of Bach's music, and were later praised by some of Bach's pupils and associates. J.S. Bach's son Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach himself published a rather vague tuning method which was close to but still not equal temperament: having only "most of" the fifths tempered, without saying which ones nor by how much.

Since 1950 there have been many other proposals and many performances of the work in different and unequal tunings, some derived from historical sources, some by modern authors. Whatever their provenances, these schemes all promote the existence of subtly different musical characters in different keys, due to the sizes of their intervals. However, they disagree as to which key receives which character:

- Herbert Anton Kellner argued from the mid-1970s until his death that esoteric considerations such as the pattern of Bach's signet ring, numerology, and more could be used to determine the correct temperament. His result is somewhat similar to Werckmeister's most familiar "correct" temperament. Kellner's temperament, with seven pure fifths and five 1/5 comma fifths, has been widely adopted worldwide for the tuning of organs. It is especially effective as a moderate solution to play 17th-century music, shying away from tonalities that have more than two flats.

- John Barnes analyzed the Well-Tempered Clavier's major-key preludes statistically, observing that some major thirds are used more often than others. His results were broadly in agreement with Kellner's and Werckmeister's patterns. His own proposed temperament from that study is a 1/6 comma variant of both Kellner (1/5) and Werckmeister (1/4), with the same general pattern tempering the naturals, and concluding with a tempered fifth B–F♯.

- Mark Lindley, a researcher of historical temperaments, has written several surveys of temperament styles in the German Baroque tradition. In his publications he has recommended and devised many patterns close to those of Neidhardt, with subtler gradations of interval size. Since a 1985 article in which he addressed some issues in the Well-Tempered Clavier, Lindley's theories have focused more on Bach's organ music than the harpsichord or clavichord works.

Title page tuning interpretations

More recently there has been a series of proposals of temperaments derived from the handwritten pattern of loops on Bach's 1722 title page. These loops (though truncated by a later clipping of the page) can be seen at the top of the title page image at the beginning of the article.

- Andreas Sparschuh, in the course of studying German Baroque organ tunings, assigned mathematical and acoustic meaning to the loops. Each loop, he argued, represents a fifth in the sequence for tuning the keyboard, starting from A. From this Sparschuh devised a recursive tuning algorithm resembling the Collatz conjecture in mathematics, subtracting one beat per second each time Bach's diagram has a non-empty loop. In 2006 he retracted his 1998 proposal based on A=420 Hz, and replaced it with another at A=410 Hz.

- Michael Zapf in 2001 reinterpreted the loops as indicating the rate of beating of different fifths in a given range of the keyboard in terms of seconds-per-beat, with the tuning now starting on C.

- John Charles Francis in 2004 performed a mathematical analysis of the loops using Mathematica under the assumption of beats per second. In 2004, he also distributed several temperaments derived from BWV 924.[19]

- Bradley Lehman in 2004 proposed[20] a 1/6 and 1/12 comma layout derived from Bach's loops, which he published in 2005 in articles of three music journals. Reaction to this work has been both vigorous and mixed, with other writers producing further speculative schemes or variants.

- Daniel Jencka in 2005 proposed[21] a variation of Lehman's layout where one of the 1/6th commas is spread over three fifths (G♯–D♯–A♯/B♭), resulting in a 1/18th comma division. Motivations for Jencka's approach involve an analysis of the possible logic behind the figures themselves and his belief that a wide fifth (B♭–F) found in Lehman's interpretation is unlikely in a well-temperament from the time.

- Graziano Interbartolo and others in 2006 proposed[22] a tuning system deduced from the WTK title page. Their work was also published in a book: Bach 1722 – Il temperamento di Dio – Le scoperte e i significati del 'Wohltemperirte Clavier', p. 136 – Edizioni Bolla, Finale Ligure.

Nevertheless, some musicologists say it is insufficiently proven that Bach's looped drawing signifies anything reliable about a tuning method. Bach may have tuned differently per occasion, or per composition, throughout his career.

- David Schulenberg, in his book The Keyboard Music of J. S. Bach, allows that Lehman's argument is "ingenious" but counters that it "lacks documentary support (if the swirls were so important, why did Bach's students not copy them accurately, if at all?")[23] and concludes that the swirls cannot "be unambiguously interpreted as a code for a particular temperament".[24]

- Luigi Swich, in his article "Further thoughts on Bach's 1722 temperament",[25] more recently presents an alternative reading from that of Bradley Lehman and others of Johann Sebastian Bach's tuning method as derived from the title-page calligraphic drawing. It differs in significant details, resulting in a circulating but unequal temperament using 1/5 Pythagorean-comma fifths that is effective through all 24 keys and, most important, tunable by ear without an electronic tuning device. It is based on the synchronicity between the fifth F–C and the third F–A (c. 3 beats per second) and between the fifth C–G and the third C–E (c. 2 beats per second). Such a system is reminiscent of Herbert Anton Kellner's 1977 temperament and even more, among the others, the temperament of the 1688 Arp Schnitger organ in Norden, St Ludgeri and the temperament later described by Carlo Gervasoni in his La scuola della musica (Piacenza, 1800). Such a system with all its major thirds more or less sharp is confirmed by Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg's report about the way a famous student of Bach's, Johann Philipp Kirnberger, was taught to tune in his lessons with Bach. It allows all 24 keys to be played through without changing tuning nor unpleasant intervals, but with varying degrees of difference-the temperament being unequal, and the keys not all sounding the same. Compared to Werckmeister III, the other 24 keys-circulating temperament, Bach's tuning is much more differentiated with its 8 (instead of Werckmeister's 4) different kinds of major thirds. The manuscript Bach P415 in Berlin Staatsbibliothek is the only known copy of the WTC to show this drawing which represents, a bit cryptically in Bach's spirit, the purpose for which the masterpiece was written and its solution at the same time. Not surprisingly, since this is most probably the working copy that Johann Sebastian Bach used in his classes.

Content

Each Prelude is followed by a Fugue in the same key. In each book the first Prelude and Fugue is in C major, followed by a Prelude and Fugue in its parallel minor key (C minor). Then all keys, each major key followed by its parallel minor key, are followed through, each time moving up a half tone: C → C♯ → D → E♭ → E → F → F♯ → ... ending with ... → B♭ → B.

Book I

The first book of the Well-Tempered Clavier was composed in the early 1720s, with Bach's autograph dated 1722. Apart from the early versions of several preludes included in W. F. Bach's Klavierbüchlein (1720) there is an almost complete collection of "Prelude and Fughetta" versions predating the 1722 autograph, known from a later copy by an unidentified scribe.[26]

No. 1: Prelude and Fugue in C major, BWV 846

Early version BWV 846a of the Prelude in Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach (No. 14: "Praeludium 1"). The prelude is a seemingly simple progression of arpeggiated chords, one of the connotations of 'préluder' as the French lutenists used it: to test the tuning. Bach used both g-sharp and a-flat into the harmonic meandering.

No. 2: Prelude and Fugue in C minor, BWV 847

commons. Prelude also in WFB Klavierbüchlein, No. 15: Praeludium 2.

No. 3: Prelude and Fugue in C-sharp major, BWV 848

commons. Prelude also in WFB Klavierbüchlein, No. 21: Praeludium [8].

No. 4: Prelude and Fugue in C-sharp minor, BWV 849

commons. Prelude also in WFB Klavierbüchlein, No. 22: Praeludium [9].

No. 5: Prelude and Fugue in D major, BWV 850

commons. Prelude also in WFB Klavierbüchlein, No. 17: Praeludium 4.

No. 6: Prelude and Fugue in D minor, BWV 851

commons. Prelude also in WFB Klavierbüchlein, No. 16: Praeludium 3.

No. 7: Prelude and Fugue in E-flat major, BWV 852

No. 8: Prelude and Fugue in E-flat minor, BWV 853

commons. Prelude also in WFB Klavierbüchlein, No. 23: Praeludium [10]. The fugue was transposed from D minor.

No. 9: Prelude and Fugue in E major, BWV 854

commons. Prelude also in WFB Klavierbüchlein, No. 19: Praeludium 6.

No. 10: Prelude and Fugue in E minor, BWV 855

commons. Early version BWV 855a of the Prelude in Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach (No. 18: "Praeludium 5").

No. 11: Prelude and Fugue in F major, BWV 856

commons. Prelude also in WFB Klavierbüchlein, No. 20: Praeludium 7.

No. 12: Prelude and Fugue in F minor, BWV 857

commons. Prelude also in WFB Klavierbüchlein, No. 24: Praeludium [11].

No. 13: Prelude and Fugue in F-sharp major, BWV 858

No. 14: Prelude and Fugue in F-sharp minor, BWV 859

No. 15: Prelude and Fugue in G major, BWV 860

No. 16: Prelude and Fugue in G minor, BWV 861

No. 17: Prelude and Fugue in A-flat major, BWV 862

No. 18: Prelude and Fugue in G-sharp minor, BWV 863

No. 19: Prelude and Fugue in A major, BWV 864

No. 20: Prelude and Fugue in A minor, BWV 865

No. 21: Prelude and Fugue in B-flat major, BWV 866

No. 22: Prelude and Fugue in B-flat minor, BWV 867

No. 23: Prelude and Fugue in B major, BWV 868

No. 24: Prelude and Fugue in B minor, BWV 869

Book II

The two major primary sources for this collection of Preludes and Fugues are the "London Original" (LO) manuscript, dated between 1739 and 1742, with scribes including Bach, his wife Anna Magdalena and his oldest son Wilhelm Friedeman, which is the basis for Version A of WTC II,[27] and for Version B, that is the version published by the 19th-century Bach-Gesellschaft, a 1744 copy primarily written by Johann Christoph Altnickol (Bach's son-in-law), with some corrections by Bach, and later also by Altnickol and others.[28]

No. 1: Prelude and Fugue in C major, BWV 870

No. 2: Prelude and Fugue in C minor, BWV 871

No. 3: Prelude and Fugue in C-sharp major, BWV 872

No. 4: Prelude and Fugue in C-sharp minor, BWV 873

No. 5: Prelude and Fugue in D major, BWV 874

No. 6: Prelude and Fugue in D minor, BWV 875

No. 7: Prelude and Fugue in E-flat major, BWV 876

No. 8: Prelude and Fugue in D-sharp minor, BWV 877

No. 9: Prelude and Fugue in E major, BWV 878

No. 10: Prelude and Fugue in E minor, BWV 879

No. 11: Prelude and Fugue in F major, BWV 880

No. 12: Prelude and Fugue in F minor, BWV 881

Prelude as a theme with variations. Fugue in three voices.

No. 13: Prelude and Fugue in F-sharp major, BWV 882

No. 14: Prelude and Fugue in F-sharp minor, BWV 883

No. 15: Prelude and Fugue in G major, BWV 884

No. 16: Prelude and Fugue in G minor, BWV 885

No. 17: Prelude and Fugue in A-flat major, BWV 886

No. 18: Prelude and Fugue in G-sharp minor, BWV 887

No. 19: Prelude and Fugue in A major, BWV 888

No. 20: Prelude and Fugue in A minor, BWV 889

No. 21: Prelude and Fugue in B-flat major, BWV 890

No. 22: Prelude and Fugue in B-flat minor, BWV 891

No. 23: Prelude and Fugue in B major, BWV 892

No. 24: Prelude and Fugue in B minor, BWV 893

Style

Musically, the structural regularities of the Well-Tempered Clavier encompass an extraordinarily wide range of styles, more so than most pieces in the literature.[citation needed] The preludes are formally free, although many of them exhibit typical Baroque melodic forms, often coupled to an extended free coda (e.g. Book I preludes in C minor, D major, and B-flat major). The preludes are also notable for their odd or irregular numbers of measures, in terms of both the phrases and the total number of measures in a given prelude.

Each fugue is marked with the number of voices, from two to five. Most are three- and four-voiced fugues, and there are only two five-voiced (BWV 849 and 867) fugues and one two-voiced (BWV 855). The fugues employ a full range of contrapuntal devices (fugal exposition, thematic inversion, stretto, etc.), but are generally more compact than Bach's fugues for organ.

Several attempts have been made to analyse the motivic connections between each prelude and fugue,[29] – most notably Wilhelm Werker[30] and Johann Nepomuk David[31] The most direct motivic reference appears in the B major set from Book 1, in which the fugue subject uses the first four notes of the prelude, in the same metric position but at half speed.[32]

Reception

Both books of the Well-Tempered Clavier were widely circulated in manuscript, but printed copies were not made until 1801, by three publishers almost simultaneously in Bonn, Leipzig and Zurich.[33] Bach's style went out of favour in the time around his death, and most music in the early Classical period had neither contrapuntal complexity nor a great variety of keys. But, with the maturing of the Classical style in the 1770s, the Well-Tempered Clavier began to influence the course of musical history, with Haydn and Mozart studying the work closely.

Mozart transcribed some of the fugues of the Well-Tempered Clavier for string ensemble:[34][35]

- BWV 853 → K. 404a/1

- BWV 871 → K. 405/1

- BWV 874 → K. 405/5

- BWV 876 → K. 405/2

- BWV 877 → K. 405/4

- BWV 878 → K. 405/3

- BWV 882 → K. 404a/3

- BWV 883 → K. 404a/2

Fantasy No. 1 with Fugue, K. 394 is one of Mozart's own compositions showing the influence the Well-Tempered Clavier had on him.[36][37] Beethoven played the entire Well-Tempered Clavier by the time he was eleven, and produced an arrangement of BWV 867, for string quintet.[38][39][40][41][42][43]

Bach's example inspired numerous composers of the 19th century, for instance in 1835 Chopin started composing his 24 Preludes, Op. 28, inspired by the Well-Tempered Clavier. In the 20th century Dmitri Shostakovich wrote his 24 Preludes and Fugues, an even closer reference to Bach's model. Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco wrote Les Guitares bien tempérées (The Well-Tempered Guitars), a set of 24 preludes and fugues for two guitars, in all 24 major and minor keys, inspired in both title and structure by Bach's work.

First prelude of Book I

The best-known piece from either book is the first prelude of Book I. Anna Magdalena Bach wrote a short version of this prelude in her 1725 Notebook (No. 29).[44] The accessibility of this C major prelude has made it one of the most commonly studied piano pieces for students completing their introductory training.[citation needed] This prelude also served as the basis for the Ave Maria of Charles Gounod.

Tenth prelude of Book I

Alexander Siloti proposed a piano arrangement of the early version of Prelude and Fugue in E minor (BWV 855a), transposed into a Prelude in B minor.

Recordings

The first complete recording of the Well-Tempered Clavier was made on the piano by Edwin Fischer for EMI between 1933 and 1936.[45] The second was made by Wanda Landowska on harpsichord for RCA Victor in 1949 (Book 1) and 1952 (Book 2).[46] The first complete recording of the work on a clavichord was made by Ralph Kirkpatrick in 1959 (Book 1) and 1967 (Book 2) for Deutsche Grammophon. Daniel Chorzempa made the first recording using multiple instruments (harpsichord, clavichord, organ, and fortepiano) for Philips in 1982.[47] Artists to have recorded the collection twice include Ralph Kirkpatrick (once on clavichord and once on harpsichord) and Angela Hewitt, João Carlos Martins, András Schiff, Rosalyn Tureck, and Tatiana Nikolayeva (all on piano). Anthony Newman has recorded it three times – twice on harpsichord and once on piano. As of 2013, over 150 recordings have been documented,[48] including the above keyboard instruments as well as transcriptions for ensembles and also synthesizers. Wendy Carlos recorded the Prelude and Fugue in E-flat Major and the Prelude and Fugue in C Minor (both from Book I) in versions for Moog synthesizer on her album "Switched-On Bach" (1968).

Audio of Book I

Harpsichord performances of various parts of Book I by Martha Goldstein are in the public domain.[49] Such harpsichord performances may, for instance, be tuned in equal temperament,[50] or in Werckmeister temperament.[51] In addition to Martha Goldstein, Raymond Smullyan is another well-known artist for whom several performances from Book I are in the public domain.[52]

In March 2015, the pianist Kimiko Douglass-Ishizaka released a new and complete recording of Book 1 into the public domain.[53] Her performances are available below, beginning with the Prelude No. 1 in C Major (BWV 846):

Audio of Book II

Following are public domain recordings from parts of Book 2:

References

- ^ Bach, Johann Sebastian; Novack, Saul (1983). "The Well-Tempered Clavier: Books I and II, complete". ISBN 978-0-486-24532-4.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John, eds. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John, eds. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John, eds. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John, eds. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ The Diapason Press – General Series: John Wilson, "Thirty Preludes" in all (24) keys for lute

- ^ John H. Baron. A 17th-Century Keyboard Tablature in Brasov, JAMS, xx (1967), pp. 279–85.

- ^ Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John, eds. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John, eds. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John, eds. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Karl Geiringer. The Bach Family: Seven Generations of Creative Genius, pp. 268–9. Oxford University Press, 1954.

- ^ Oswald Bill, Christoph Grosspietsch. Christoph Graupner: Thematisches Verzeichnis der musikalischen Werke. Carus, 2005. ISBN 3-89948-066-X

- ^ Fredrich Suppig: Labyrinthus musicus, Calculus musicus, facsimile of the manuscripts. Tuning and Temperament Library, Volume 3, edited by Rudolf Rasch. Diapason Press, Utrecht, 1990.

- ^ Jean M. Perreault. The Thematic Catalogue of the Musical Works of Johann Pachelbel, p. 84. Scarecrow Press, Lanham, Md. 2004. ISBN 0-8108-4970-4.

- ^ Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 5th ed, 1954, Vol. IX, p. 223

- ^ The Well-Tempered Clavier – notes, Estonian Record Productions

- ^ Bach, J. S. (2004). Palmer, Willard A. (ed.). J. S. Bach: The Well-Tempered Clavier. Los Angeles: Alfred Music. p. 4. ISBN 0-88284-831-3. Retrieved May 10, 2010.

- ^ "Mr. Kirnberger has more than once told me as well as others about how the famous Joh. Seb. Bach, during the time when the former was enjoying musical instruction at the hands of the latter, confided to him the tuning of his clavier, and how the master expressly required of him that he tune all the thirds sharp." — Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg, 1776. Quoted in David, Hans T.; Mendel, Arthur, eds. The Bach Reader (Revised, with a Supplement), W. W. Norton & Company, 1966, p. 261. ISBN 0-393-00259-4

- ^ The Keyboard Tuning of J. S. Bach, John Charles Francis

- ^ LaripS.com: Johann Sebastian Bach's tuning, Bradley Lehman, 2005

- ^ The Tuning Script from Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier: A Possible 1/18th PC Interpretation, Daniel Jencka, 2006

- ^ Bach 1722 – Il temperamento di Dio

- ^ David Schulenberg, The Keyboard Music of J. S. Bach, Second Edition, Routledge, 2006, p. 452, ISBN 978-0-415-97400-4

- ^ David Schulenberg, The Keyboard Music of J. S. Bach, Second Edition, Routledge, 2006, p. 18, ISBN 978-0-415-97400-4

- ^ Luigi Swich, "Further thoughts on Bach's 1722 temperament" in "Early Music" XXXIX/3, August 2011, pp. 401–407

- ^ Bach Digital Source 5418 at www

.bachdigital .de - ^ GB-Lbl Add. MS. 35021 at www

.bachdigital .de - ^ D-B Mus. ms. Bach P 430 at www

.bachdigital .de - ^ Leikin, Anatole. "The Mystery of Chopin's Préludes", (Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2015) p. 48.

- ^ Werker, Wilhelm. Studien über die Symmetrie im Bau der Fugen und die motivische Zusammengehörigkeit der Präludien und Fugen des "Wohlemperierten Klaviers" von Johann Sebastian Bach (Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel, 1922)

- ^ David, Johann Nepomuk. Das Wohltemperierte Klavier: Der Versuch einer Synopsis (Göttigen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1962)

- ^ Bach, J. S. Das Wohltemperierte Klavier: Teil I (München: G. Henle Verlag, 1997), pp. 110-3.

- ^ Kassler, Michael (2006). "Broderip, Wilkinson and the First English Edition of the '48'". The Musical Times. 147 (Summer 2006): 67–76. doi:10.2307/25434385. ISSN 0027-4666. Retrieved May 10, 2010. [dead link]

- ^ Preludes and Fugues, K.404a: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- ^ Köchel, Ludwig Ritter von (1862). Chronologisch-thematisches Verzeichniss sämmtlicher Tonwerke Wolfgang Amade Mozart's (in German). Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. OCLC 3309798. Archived from the original on 12 February 2008., No. 405, pp. 328–329

- ^ Michelle Rasmussen

- ^ Brown, A. Peter, The Symphonic Repertoire (Volume 2). Indiana University Press (ISBN 025333487X), pp. 423-432 (2002).

- ^ "Hess 38" is Beethoven's arrangement of "Book 1 – Fugue No. 22 in B flat minor" (BWV 867).

- ^ McKay, Cory. "The Bach Reception in the 18th and 19th century" at www

.music .mcgill .ca - ^ Schenk, Winston & Winston (1959), p. 452

- ^ Daniel Heartz. Mozart, Haydn and Early Beethoven: 1781-1802, p. 678. W. W. Norton & Company, 2008. ISBN 9780393285789

- ^ Kerst (1904), p. 101

- ^ Edward Noel Green. Chromatic Completion in the Late Vocal Music of Haydn and Mozart: A Technical, Philosophic, and Historical Study, p. 273 New York University. ISBN 9780549794516

- ^ Notebooks for Anna Magdalena Bach: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project at IMSLP website

- ^ Gramophone, "Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier"

- ^ Bach Cantatas Website, "Well-Tempered Clavier Book I, BWV 846–869 Recordings – Part 1"

- ^ Bach Cantatas Website, "Well-Tempered Clavier Book I, BWV 846–869 Recordings – Part 5"

- ^ Bach Cantatas Website, "Well-Tempered Clavier Book I, BWV 846–869 Recordings – Part 8"

- ^ The portions of Book I performed by Martha Goldstein and in the public domain include the following (all on harpsichord): "Prelude in C major" (BWV 846), Fugue in C major (BWV 846), Prelude No. 2 in C minor (BWV 847), Fugue No. 2 in C minor (BWV 847), ”Fugue No. 4 in C-sharp minor” (BWV 849), ”Prelude No. 5 in D major” (BWV 850), ”Fugue No. 5 in D major” (BWV 850), ”Prelude No. 6 in D minor” (BWV 851), ”Fugue No. 6 in D minor” (BWV 851), ”Prelude No. 21 in B-flat major” (BWV 866), and ”Fugue No. 21 in B-flat major” (BWV 866).

- ^ "Book 1 of The Well-tempered Clavier by J.S. Bach – Prelude in C major (BWV 846)", performed on a French harpsichord tuned in equal temperament by Robert Schröter.

- ^ "Book 1 of The Well-tempered Clavier by J.S. Bach – Prelude in C major (BWV 846)", performed on a French harpsichord tuned in Werckmeister temperament by Robert Schröter.

- ^ The portions of Book I performed by Raymond Smullyan and in the public domain include the following (all on piano): "Prelude and Fugue No. 13 in F sharp major" (BWV 858), "Prelude and Fugue No. 18 in G sharp minor" (BWV 863), "Prelude and Fugue No. 22 in B flat minor" (BWV 867), and "Prelude and Fugue No. 23 in B major" (BWV 868).

- ^ The Open Well-Tempered Clavier Website, "The Open Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1"

Sources

- Kirkpatrick, Ralph. Interpreting Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier: A Performer's Discourse of Method (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987). ISBN 0-300-03893-3.

- Ledbetter, David. Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier: The 48 Preludes and Fugues (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002). ISBN 0-300-09707-7.

External links

Interactive media

- (Adobe Flash) Exploring Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier – Korevaar (piano), Goeth (organ), Parmentier (harpsichord). Direct access to the fugues.

Sheet music

- Open-source edition of the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I available in MuseScore, MusicXML, MIDI, PDF formats, released under CC0

- Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I, Book II: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Johann Sebastian Bach's Werke. Das Wohltemperirte Clavier, Erster Theil / Zweiter Theil (Leipzig 1851): Indiana University School of Music score in GIF format

- Scores of some of the Preludes and Fugues of the Well-Tempered Clavier through the Mutopia Project

- Bach's manuscript of Book II of the Well-Tempered Clavier: Facsimile of British Library Add MS 35021

Recordings

- Free piano recording of Book 1 by Kimiko Ishizaka (Open Well-Tempered Clavier project)

- Complete, free midi recordings of books I & II by John Sankey

- Free midi recording of book II by Prof. Yo Tomita of The Queen's University, Belfast

- Complete, free midi recordings of books I and II by Alan Kennington

- Piano Society – Free audio records of WTC, MP3 files, video

On tuning systems

- All existing 18th century quotes on J.S.Bachs temperament

- Larips.com – "Bach" tuning resources – interpreted by Bradley Lehman

- Bach- and Well-Temperaments for Western Classical Music

- Rosetta Revisited — Interpreted by Dominic Eckersley

Descriptions and analyses

- J.S. Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier / In-depth Analysis and Interpretation by Siglind Bruhn. Full text of the 1993 book.

- Animated visualizations of the music by Tim Smith and David Korevaar

- Graphical motif extraction for The Well-Tempered Clavier 1 and The Well-Tempered Clavier 2

- Essay by Yo Tomita about Book I of The Well-Tempered Clavier

- Program notes from the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra

- Interpretation and analysis of JS Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier by Philip Goeth (includes audio samples)

- Lowrance, Rachel A. (2013) "Instruction, Devotion, and Affection: Three Roles of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier," Musical Offerings: Vol. 4: No. 1, Article 2. Available at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings/vol4/iss1/2