Tiridates III of Armenia

| Tiridates III the Great | |

|---|---|

19th-century illustration of Tiridates | |

| King of Armenia | |

| Reign | 298–c. 330 AD |

| Predecessor | Khosrov II |

| Successor | Khosrov III the Small |

| Born | 250s AD |

| Died | c. 330 AD |

| Burial | |

| Consort | Ashkhen |

| Issue | Khosrov III the Small Salome of Armenia |

| Dynasty | Arsacid dynasty |

| Father | Khosrov II of Armenia |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism (before 301)[1] Armenian Christianity (after 301) |

| Part of a series on |

| Oriental Orthodoxy |

|---|

|

| Oriental Orthodox churches |

|

|

Tiridates III (c. 250s – c. 330), also known as Tiridates the Great or Tiridates IV, was the Armenian Arsacid king[2] from c. 298 to c. 330. In the early 4th century (the traditional date is 301), Tiridates proclaimed Christianity as the state religion of Armenia, making the Armenian kingdom the first state to officially embrace Christianity.[3]

Name

[edit]The name Tiridates is the Greek variant of the Parthian name Trdat, meaning "created by Tir."[4] Although Tir does not appear in the Avesta, he is a prominent yazata (angelic divinity) in the Zoroastrian religion.[5] The name also appears in other Greek variants, such as Terdates, Teridates, Teridatios, and Tiridatios. It appears in Syriac as Turadatis and in Latin as Tiridates.[6]

Early childhood

[edit]Tiridates III was the son of Khosrov II of Armenia, the latter being assassinated in 252 by a Parthian agent named Anak under orders from Ardashir I. Tiridates had at least one sibling, a sister called Khosrovidukht and was the namesake of his paternal grandfather, Tiridates II of Armenia. Anak was captured and executed along with most of his family, while his son, Gregory the Illuminator, was sheltered in Caesaria, in Cappadocia. As the only surviving heir to the throne, Tiridates was quickly taken away to Rome soon after his father's assassination while still an infant. He was educated in Rome and was skilled in languages and military tactics;[7][8] in addition he firmly understood and appreciated Roman law. The Armenian historian Movses Khorenatsi describes him as a strong and brave warrior, who participated in combat against his enemies, and personally led his army to victory in many battles.

Kingship

[edit]

In 270, the Roman emperor Aurelian engaged the Sassanids on the eastern front and he was able to drive them back. Tiridates, as the true heir to the now Persian-occupied Armenian throne, came to Armenia and quickly raised an army and drove the enemy out in 298.

For a while, fortune appeared to favour Tiridates. He not only expelled his enemies, but he carried his arms into Assyria. At the time the Persian Empire was in a distracted state. The throne was disputed by the ambition of two contending brothers, Hormuz and Narses.[citation needed] The civil war was, however, soon terminated and Narses was universally acknowledged as King of Persia. Narses then directed his whole force against the foreign enemy. The contest then became too unequal. Tiridates once more took refuge with the Romans. The Roman-Armenian alliance grew stronger, especially while Diocletian ruled the empire. This can be attributed to the upbringing of Tiridates, the consistent Persian aggressions and the murder of his father by Anak. With Diocletian's help, Tiridates pushed the Persians out of Armenia.[7] In 299, Diocletian left the Armenian state in a quasi-independent and protectorate status possibly to use it as a buffer in case of a Persian attack.[9]

In 297, Tiridates married an Alanian princess called Ashkhen, by whom he had three children: a son called Khosrov III, a daughter called Salome, and another daughter who married St. Husik I, one of the earlier Catholicoi of the Armenian Apostolic Church.

Conversion

[edit]Tiridates III the Great Սբ. Տրդատ Մեծ թագավոր | |

|---|---|

Tiridates III the Great, the Great King of the Armenians. | |

| King of Armenia | |

| Resting place | Kemah, Erzincan, Armenia |

| Venerated in | Oriental Orthodoxy Catholic Church |

| Feast | Saturday before fifth Sunday after Pentecost (Armenian Apostolic Church)[10] |

| Attributes | Crown Sword Cross Globus cruciger |

| Patronage | Armenia |

The traditional story of the conversion of the king and the nation is primarily based on the fifth-century Armenian history attributed to Agathangelos.[11][12] It tells of Gregory the Illuminator, the son of Anak, who was brought up as a Christian and, feeling guilt for his own father's sin, joined the Armenian army and worked as a secretary to the king. Christianity in Armenia had a strong footing by the end of the 3rd century, but the nation by and large still followed Zoroastrianism. Tiridates was no exception as he too worshiped various ancient gods. During a Zoroastrian religious ceremony Tiridates ordered Gregory to place a flower wreath at the foot of the statue of the goddess Anahit in Eriza. Gregory refused, proclaiming his Christian faith. This act infuriated the king. His fury was only exacerbated when several individuals declared that Gregory was in fact, the son of Anak, the traitor who had killed Tiridates's father. Gregory was tortured and finally thrown in Khor Virap, a deep underground dungeon.

During the years of Gregory's imprisonment, a group of virgin nuns, led by Gayane, came to Armenia as they fled the Roman persecution of their Christian faith. Tiridates heard about the group and the legendary beauty of one of its members, Rhipsime. He brought them to the palace and demanded to marry the beautiful virgin; she refused. The king had the whole group tortured and killed. After this event, he fell ill and according to legend, adopted the behavior of a wild boar, aimlessly wandering around in the forest. Khosrovidukht had a dream wherein Gregory was still alive in the dungeon, and he was the only one able to cure the king. At this point it had been 13 years since his imprisonment, and the odds of him being alive were slim. They retrieved him, and, despite being incredibly malnourished, he was still alive. He was kept alive by a kind-hearted woman who threw a loaf of bread down in Khor Virap every day for him.

Tiridates was brought to Gregory and was miraculously cured of his illness. Persuaded by the power of the cure, the king immediately proclaimed Christianity the official state religion. Thus, Armenia became a nominally Christian kingdom and the first state to officially adopt Christianity. Tiridates appointed Gregory as Catholicos of the Armenian Apostolic Church.

The conversion to Christianity proved to be a pivotal event in Armenian history. According to the scholar of Zoroastrianism Mary Boyce, it seems that the Christianisation of Armenia by the Arsacids of Armenia was partly in defiance of the Sassanids.[13]

Rest of reign

[edit]The switch from the traditional Zoroastrianism to Christianity was not an easy one. Tiridates often used force to impose this new faith upon the people and many armed conflicts ensued, due to Zoroastrianism being deeply rooted in the Armenian people. An actual battle took place between the king's forces and the Zoroastrian camp, resulting in the weakening of polytheistic military strength. Tiridates thus spent the rest of his life trying to eliminate all ancient beliefs and in doing so destroyed countless statues, temples and written documents. As a result, little is known from local sources about ancient Armenian history and culture. The king worked feverishly to spread the faith and died in 330. Movses Khorenatsi states that several members of the nakharar families conspired against Tiridates and eventually poisoned him.[14]

Tiridates III, Ashkhen and Khosrovidukht are saints in the Armenian Apostolic Church, and by extension all of the Oriental Orthodox Churches, and their feast day is on the Saturday after the fifth Sunday after Pentecost. On this feast day the hymn "To the Kings" is sung.[15] Their feast day is usually around June 30.

Gallery

[edit]-

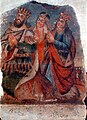

18th century ilustration of Tiridates III

-

Gregory the Illuminator baptizes Tiridates III

-

Tiridates III with his wife Ashkhen and sister Khosrovidukht by Naghash Hovnatan.

-

Tiridates III and Gregory the Illuminator, Echmiadzin.

-

Gregory the Illuminator baptizes Tiridates III

References

[edit]- ^ Curtis 2016, p. 185; De Jong 2015, pp. 119–120, 123–125; Russell 1987, pp. 170–171

- ^ Edwards et al. 1970.

- ^ Binns 2002, p. 30.

- ^ Schmitt 2005; Russell 1987, p. 386; Rapp 2014, p. 263

- ^ Russell 1987, p. 382.

- ^ Russell 1987, p. 386.

- ^ a b Grigoryan 1987.

- ^ Movses Khorenatsʻi 1997, 2.79.

- ^ Barnes 1981, p. 18.

- ^ Domar 2002, p. 443.

- ^ Bournoutian 2006, p. 47.

- ^ Agathangelos 1976.

- ^ Boyce 2001, p. 84: "[...] and there is no doubt that during the latter part of the Parthian period Armenia was a predominantly Zoroastrian adhering land. Thereafter, it embraced Christianity (partly, it seems, in defiance of the Sasanians) [...].

- ^ Movses Khorenatsʻi 1997, 2.92.

- ^ Biographies of Armenian Saints 2012.

Bibliography

[edit]- Agathangelos (1976). History of the Armenians. Translation and commentary by Robert W. Thomson (First ed.). Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-87395-323-1.

- Barnes, Timothy David (1981). Constantine and Eusebius. Harvard University Press.

- Binns, John (2002). An Introduction to the Christian Orthodox Churches. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66738-0.

- "Biographies of Armenian Saints, St Drtad (250-330)". St. Nersess Armenian Seminary. Archived from the original on 14 August 2012.

- Bournoutian, George A. (2006). A Concise History of the Armenian People (Fifth ed.). Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers. ISBN 1-56859-141-1.

- Boyce, Mary (2001). Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Psychology Press.

- Chaumont, Marie-Louise (1996). "Une visite du roi d'Arménie Tiridate III à l'empereur Constantin à Rome?" [A Visit from Armenian King Tiridates III to Emperor Constantine in Rome?]. In Garsoïan, Nina (ed.). L'Arménie et Byzance: Histoire et culture [Armenia and Byzantium: History and Culture] (in French). Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne. pp. 55–66. ISBN 9782859448240.

- Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh (2016). "Ancient Iranian Motifs and Zoroastrian Iconography". In Williams, Markus; Stewart, Sarah; Hintze, Almut (eds.). The Zoroastrian Flame Exploring Religion, History and Tradition. I.B. Tauris. pp. 179–203. ISBN 9780857728159.

- De Jong, Albert (2015). "Armenian and Georgian Zoroastrianism". In Stausberg, Michael; Vevaina, Yuhan Sohrab-Dinshaw; Tessmann, Anna (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Domar: The Calendrical and Liturgical Cycle of the Armenian Apostolic Orthodox Church. Armenian Orthodox Theological Research Institute. 2002.

- Edwards, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen; Gadd, Cyril John; Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière; Boardman, John; Walbank, Frank William; Lewis, David Malcolm; Bowman, Alan; Astin, A. E.; Garnsey, Peter (1970). The Cambridge Ancient History: Volume 12, The Crisis of Empire, AD 193-337. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-30199-2.

- Grigoryan, V. (1987). "Trdat G Mets" Տրդատ Գ Մեծ [Tiridates III the Great]. In Hambardzumyan, Viktor; et al. (eds.). Haykakan sovetakan hanragitaran Հայկական սովետական հանրագիտարան [Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia] (in Armenian). Vol. 12. Erevan: Hay sovetakan hanragitaran hratarakč῾ut῾yun. p. 94.

- Movses Khorenatsʻi (1997). Sargsyan, Gagik (ed.). Hayotsʻ Patmutʻyun, E dar Հայոց Պատմություն, Ե Դար [History of Armenia, 5th Century] (in Armenian). Erevan: Hayastan. ISBN 5-540-01192-9.

- Rapp, Stephen H. (2014). The Sasanian World through Georgian Eyes: Caucasia and the Iranian Commonwealth in Late Antique Georgian Literature. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4724-2552-2.

- Russell, James R. (1987). Zoroastrianism in Armenia. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674968509.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (2005). "Personal Names, Iranian iv. Parthian Period". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York: Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation.

General references

[edit]- Kettenhofen, Erich (2002). "Die Anfänge des Christentums in Armenien" [The Beginnings of Christianity in Armenia]. Handēs Amsōreay (in German). 116: 45–104. OCLC 5377086.

- Kettenhofen, Erich (1995). Tirdād und die Inschrift von Paikuli: Kritik der Quellen zur Geschichte Armeniens im späten 3. und frühen 4. Jh. n. Chr [Tirdād and the Paikuli Inscription: Criticism of the Sources on the History of Armenia in the Late 3rd and Early 4th Centuries AD] (in German). Reichert Verlag. ISBN 9783882268256.

- Manaseryan, Ṛuben (1997). Hayastaně Artavazditsʻ minchʻev Trdat Mets Հայաստանը Արտավազդից մինչև Տրդատ Մեծ [Armenia from Artavazd to Trdat the Great] (in Armenian). Erevan: Areg. OCLC 606657781.

- Mardirossian, Aram (2001). "Le synode de Valarsapat (491) et la date de la conversion au christianisme du Royaume de Grande Arménie (311)". Revue des Études Arméniennes. 28: 249–260. doi:10.2143/REA.28.0.505082. ISSN 0080-2549.

- Thomson, Robert W. (1997). "Constantine and Trdat in Armenian tradition". Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 50 (1/3): 277–289. ISSN 0001-6446. JSTOR 23658223.

- Walburg, Karin Mosig (2006). "Der Armenienkrieg des Maximinus Daia" [The Armenian War of Maximinus Daia]. Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte (in German). 55 (2): 247–255. doi:10.25162/historia-2006-0016. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 4436812. S2CID 252446106.

- Zuckerman, Constantin (1994). "Les campagnes des tétrarques, 296-298. Notes de chronologie" [The Campaigns of the Tetrarchs, 296-298. Chronology Notes]. Antiquité Tardive (in French). 2: 65–70. doi:10.1484/J.AT.2.301153. ISSN 1250-7334.