Management of multiple sclerosis

Several therapies for multiple sclerosis (MS) exist, although there is no known cure. Multiple sclerosis is a chronic inflammatory demyelinating disease that affects the central nervous system (CNS).

The most common initial course of the disease is the relapsing-remitting subtype, which is characterized by unpredictable attacks (relapses) followed by periods of relative remission with no new signs of disease activity. After some years, many of the people who have this subtype begin to experience neurologic decline without acute relapses. Other, less common, courses of the disease are the primary progressive (decline from the beginning without attacks) and the progressive-relapsing (steady neurologic decline and superimposed attacks). Different therapies are used for patients experiencing acute attacks, for patients who have the relapsing-remitting subtype, for patients who have the progressive subtypes, for patients without a diagnosis of MS who have a demyelinating event, and for managing the various consequences of MS.

The primary aims of therapy are returning function after an attack, preventing new attacks, and preventing disability. As with any medical treatment, medications used in the management of MS have several adverse effects, and many possible therapies are still under investigation. At the same time different alternative treatments are pursued by many patients, despite the paucity of supporting, comparable, replicated scientific study.

This article focuses on therapies for standard MS; borderline forms of MS have particular treatments that are excluded.

Management of acute attacks

During symptomatic attacks, patients may be hospitalized. As of 2007, administration of high doses of intravenous corticosteroids, such as methylprednisolone,[1][2] is the routine therapy for acute relapses. This is administered over a period of three to five days, and has a well-established efficacy in promoting a better recovery from disability.[3][4]

The aim of this kind of treatment is to end the attack sooner and leave fewer lasting deficits in the patient. Although generally effective in the short term for relieving symptoms, corticosteroid treatments do not appear to have a significant impact on long-term recovery: steroids produce a rapid improvement from disability, but this improvement only lasts up to thirty days following a clinical attack and is not evident thirty-six months after the attack. This treatment does not reduce the number of patients who subsequently develop a clinical relapse.[5]

Potential side effects include osteoporosis[6] and impaired memory, the latter being reversible[7]

Recent studies suggest that steroids administered orally are just as effective at treating MS symptoms as intravenous treatment. However, short term treatment with high-dose intravenous corticosteroids does not seem to be attended by adverse effects; on the contrary, gastrointestinal symptoms and psychiatric disorders are more common with oral corticosteroids.[8]

Disease-modifying treatments

Clinically isolated syndrome

The earliest clinical presentation of relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) is the clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), that is, a single attack of a single symptom. During a CIS, there is a subacute attack suggestive of demyelination but the patient does not fulfill the criteria for diagnosis of multiple sclerosis.[9] Several studies have shown that treatment with interferons during an initial attack can decrease the chance that a patient will develop MS. These results support the use of interferon after a first clinical demyelinating event and indicate that there may be modest beneficial effects of immediate treatment compared with delayed initiation of treatment.[10][11][12]

Relapsing-remitting MS

As of 2007, six disease-modifying treatments have been approved by regulatory agencies of different countries, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) and the Japanese PMDA. Three are interferons: two formulations of interferon beta-1a (trade names Avonex and Rebif; the first given weekly, the latter three times a week),[13][14] and one of interferon beta-1b (U.S. trade name Betaseron, in Europe and Japan Betaferon).[15] Interferons are medications derived from human cytokines which help to regulate the immune system. A fourth medication is glatiramer acetate (Copaxone),[16] a mixture of polypeptides which may protect important myelin proteins by substituting itself as the target of immune system attack.[17] The fifth medication, mitoxantrone, is an immunosuppressant also used in cancer chemotherapy. Finally, the sixth is natalizumab (marketed as Tysabri), a monoclonal antibody.[18]

All six medications are modestly effective at decreasing the number of attacks and slowing progression to disability, although they differ in their efficacy rate and studies of their long-term effects are still lacking.[19][20][21][22] The percentage of non-responsive patients to each medication also varies; being around 30% with interferons.[23] Comparisons between immunomodulators (all but mitoxantrone) show that the most effective is natalizumab, .[24] Mitoxantrone is probably the most effective of them all;[25] however, its use is limited by severe cardiotoxicity.[26] This is the reason why it is mainly used to treat MS patients who have worsening relapsing-remitting or secondary progressive multiple sclerosis despite prior therapy with interferons or glatiramer acetate.

Medications also differ in ease of use, price and side effects.[27] All of these therapies are expensive and require frequent injections, with Tysabri given as intravenous infusions every four weeks,[18] Avonex requiring weekly injections,[13] Rebif three times a week,[14] and Copaxone and Betaseron daily injections.[16][15] Mitoxantrone is intravenously administered every three months as a slow infusion over at least thirty minutes.

Even with appropriate use of medication, most patients with relapsing-remitting MS still suffer from some attacks and subsequent disability.

Progressive MS

Treatment of progressive MS is more difficult than relapsing-remitting MS, and many patients do not respond to any available therapy. A wide range of medications have been used to try to slow the progression of the disease.

Mitoxantrone has shown positive effects in patients with a secondary progressive and progressive relapsing courses. It is moderately effective in reducing the progression of the disease and the frequency of relapses in patients in short-term follow-up.[22] In 2007 it was the only medication approved for secondary progressive and progressive relapsing multiple sclerosis; however, it causes dose-dependent cardiac toxicity which limits its long-term use. Interferon-beta-1b slowed progression of the disease in one clinical trial for secondary progressive MS, but not in another. However, both studies demonstrated that interferon recipients had fewer relapses and less disease activity, as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Therefore, interferons show promise in treating secondary progressive MS, but more data is needed to support their widespread use.[28]

Several trials have been designed specifically for primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS), including trials with interferons and mitoxantrone, a phase III trial of glatiramer acetate, and an open-label study of riluzole.[29] Patients with PPMS have also been included in trials of azathioprine,[30] methotrexate,[31] cladribine,[32] intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclophosphamide,[33] and studies of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. However, no treatment in these trials has been proven definitively to modify the course of the disease.[34]

Side effects of treatments

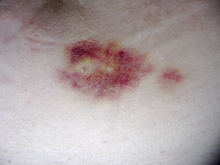

Both the interferons and glatiramer acetate are available only in injectable forms, and both can cause irritation at the injection site.

Interferons are produced in the body during illnesses such as influenza in order to help fight the infection.[35] They are responsible for the fever, muscle aches, fatigue, and headache common during influenza infections. Many patients report influenza-like symptoms when using interferon to fight MS. This reaction often lessens over time and can be treated with over-the-counter fever reducers/pain relievers like paracetamol (known in the U.S. as acetaminophen),[36] ibuprofen,[37] and naproxen.[38] Rare, but potentially serious, liver function abnormalities have also been reported with interferons, requiring that all patients treated regularly be monitored with liver function tests to ensure safe use.[39][40][41] Interferon therapy has also been shown to induce the production of anti-IFN neutralizing antibodies (NAb), usually in the second 6 months of treatment, in 3 to 45% of treated patients. However, the clinical consequences of the presence of antibodies are presently unclear: it has not been proved that these antibodies reduce efficacy of treatment. Therefore, any treatment decision should be based only on the clinical response to therapy.[42]

Glatiramer acetate is generally considered to be better tolerated than the interferons, although some patients taking glatiramer experience a post-injection reaction manifested by flushing, chest tightness, heart palpitations, breathlessness, and anxiety, which usually lasts less than thirty minutes.[20]

Mitoxantrone therapy may be associated with immunosuppressive effects and liver damage; however its most dangerous side effect is its dose-related cardiac toxicity. Careful adherence to the administration and monitoring guidelines is therefore essential; this includes obtaining an echocardiogram and a complete blood count before treatment to decide whether the therapy is suitable for the patient or the risks are too great. It is recommended that mitoxantrone be discontinued at the first signs of heart damage, infection or liver dysfunction during therapy.[43]

In phase III studies, natalizumab was highly effective and well tolerated; however, three cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) were identified in patients who had taken it in combination with interferons.[44][45] PML is a rare and progressive demyelinating disease of the brain that typically causes permanent disability or death. It is caused by infection by the JC virus (JCV), a virus thought to be present in most healthy individuals, and at first its symptoms may be similar to a MS relapse. There are no known treatments for PML; but the sooner the immune system returns to normal the higher the probabilities for recovery will be. As natalizumab was the suspected cause for these three cases of PML, it was withdrawn from the markets. An intensive safety evaluation was conducted which concluded that there was a potential risk of PML in patients taking natalizumab in combination with interferons. In 2006, natalizumab was finally re-approved as a monotherapy for patients with relapsing forms of MS.[46]

Management of the effects of MS

Disease-modifying treatments only reduce the progression rate of the disease but do not stop it. As multiple sclerosis progresses, the symptoms tend to increase. The disease is associated with a variety of symptoms and functional deficits that result in a range of progressive impairments and handicap. Management of these deficits is therefore very important.

Both drug therapy and neurorehabilitation have shown to ease the burden of some symptoms, even though neither influence disease progression. For other symptoms the efficacy of treatments is still very limited.[47]

Neurorehabilitation

Although there are few studies of rehabilitation in MS,[48][49] its general effectiveness, when conducted by a team of specialists, has been clearly demonstrated in other pathologies such as stroke[50] or head trauma.[51] As for any patient with neurologic deficits, a multidisciplinary approach is key to limiting and overcoming disability; however there are particular difficulties in specifying a ‘core team’ because people with MS may need help from almost any health profession or service at some point.[52] Neurologists will be the main physicians involved, but depending on the symptom, doctors of other medical specialties may also be helpful. Allied treatments such as physical therapy[53][54] or speech therapy[55] can also help to manage some symptoms and maintain quality of life. Treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms such as emotional distress and clinical depression should involve mental health professionals such as therapists, psychologists, and psychiatrists,[56] while neuropsychologists can help to evaluate and manage cognitive deficits.[57] Although occupational therapy has shown its efficacy in other chronic neurologic conditions[58] and some preliminary data suggests that it may be useful in MS,[59] there are not sufficient randomized controlled studies to establish its effectiveness.[58][60]

Medical treatments for symptoms

Multiple sclerosis can cause a variety of symptoms including changes in sensation (hypoesthesia), muscle weakness, abnormal muscle spasms, difficulty to move, difficulties with coordination and balance, problems in speech (known as dysarthria) or swallowing (dysphagia), visual problems (nystagmus, optic neuritis, or diplopia), fatigue and acute or chronic pain syndromes, bladder and bowel difficulties, cognitive impairment, or emotional symptoms (mainly depression). The main clinical measure of disability progression and severity of the symptoms is the Expanded Disability Status Scale or EDSS.[61] At the same time for each symptom there are different treatment options. Treatments should therefore be individualized depending both on the patient and the physician.

- Bladder: pharmacological treatments for bladder problems vary greatly depending on the origin or type of dysfunction; however, some examples of medications used are:[62] alfuzosin for retention,[63] anticholinergics such as trospium and flavoxate for urgency and incontinence,[64][65] or desmopressin for nocturia.[66][67] Non-pharmacological treatments involve the use of pelvic floor muscle training, stimulation, biofeedback, pessaries, bladder retraining, and sometimes intermittent catheterization.[68]

- Bowel: people with MS may suffer bowel problems in two ways: reduced gut mobility may follow from immobility and the drugs used to treat various impairments; and neurological control of defecation may be directly impaired.[52] Pain or difficulty with defecation can be helped with a diet change, oral laxatives or suppositories and enemas.[69]

- Cognitive and emotional: neuropsychiatric symptomatology is not rare in the course of the disease. Depression and anxiety appear in up to 80% of patients,[70] and can be treated with a variety of antidepressants;[71] selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most commonly employed.[72] Other neuropsychiatric symptoms are euphoria and disinhibition. This dyad was called "euphoria sclerotica" by the first authors that described the disease during the 19th century, and affects 10% of patients.[73][74] On the other hand, cognitive deficits appear in approximately 50% of the people with the disease.[75] Anticholinesterase drugs such as donepezil[76]—commonly used in Alzheimer disease—although not approved yet for multiple sclerosis, have shown efficacy in improving cognitive functions.[77][78] Psychological interventions are also useful in the treatment of cognitive and emotional deficits.[79][80][81][82]

- Dysphagia and dysarthria: dysphagia is a difficulty with swallowing which may cause choking and aspiration of food or liquid into the lungs, while dysarthria is a neurological motor speech disorder characterized by poor control over the subsystems and muscles responsible for speech ("articulation"). A language therapist may give advice on specific swallowing techniques, on adapting food consistencies and dietary intake, on techniques to improve and maintain speech production and clarity, and on alternative communication systems.[52][55] In the case of advanced dysphagia, food can be supplied by a nasogastric tube, which is a tube that goes through the nose directly to the stomach; or a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), which is a procedure for placing a tube into the stomach and therefore administering food directly to it. This second system, although more invasive, has better results in the long term than nasogastric intake.[83]

- Fatigue: fatigue is very common and disabling in MS, and at the same time it has a close relationship with depressive symptomatology.[84] When depression is reduced fatigue also tends to improve, so patients should be evaluated for depression before other therapeutic approaches are used.[85] In a similar way, other factors such as disturbed sleep, chronic pain, poor nutrition, or even some medications can contribute to fatigue; medical professionals are therefore encouraged to identify and modify them.[52] There are also different medications used to treat fatigue, such as amantadine[86][87] or pemoline,[88][89] as well as psychological interventions of energy conservation,[90][91] but the effects of all of them are small. Fatigue is therefore a very difficult symptom to manage.

- Pain: acute pain is mainly due to optic neuritis (with corticosteroids being the best treatment available), as well as trigeminal neuralgia, Lhermitte's sign, or dysesthesias.[92] Subacute pain is usually secondary to the disease and can be a consequence of spending too long in the same position, urinary retention, and infected skin ulcers, amongst others. Treatment will depend on cause. Chronic pain is very common and harder to treat as its most common cause is dysesthesias. Acute pain due to trigeminal neuralgia is usually successfully treated with anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine[93] or phenytoin.[94][95][96] Both Lhermitte's sign and painful dysesthesias usually respond to treatment with carbamazepine, clonazepam,[97] or amitriptyline.[98][99] Sativex is approved for treatment of pain in MS in different countries, but due to its derivation from cannabis, it is currently not available in others, such as the USA.[100] This medication is also being investigated for the management of other MS symptoms, such as spasticity,[101] and has shown long-term safety and efficacy.[102]

- Spasticity: spasticity is characterised by increased stiffness and slowness in limb movement, the development of certain postures, an association with weakness of voluntary muscle power, and with involuntary and sometimes painful spasms of limbs.[52] A physiotherapist can help to reduce spasticity and avoid the development of contractures with techniques such as passive stretching.[103] There is evidence, albeit limited, of the clinical effectiveness of baclofen,[104] dantrolene,[105] diazepam,[106] and tizanidine.[107][108][109] In the most complicated cases intrathecal injections of baclofen can be used.[110] There are also palliative measures like castings, splints or customised seatings.[52]

- Vision: different drugs as well as optic compensatory systems and prisms can be used to improve the symptoms of nystagmus.[111][112][113] Surgery can also be used in some cases for this problem.[114]

Unfortunately, other symptoms, such as ataxia, tremor or sensory losses, do not have proven treatments.[52]

Therapies under investigation

Scientists continue their extensive efforts to create new and better therapies for MS. There are a number of treatments under investigation that may curtail attacks or improve function. Some of these treatments involve the combination of drugs that are already in use for multiple sclerosis, such as the combination of mitoxantrone and glatiramer acetate (Copaxone).[115] However most treatments already in clinical trials involve drugs that are used in other diseases. These are the cases of alemtuzumab (trade name Campath),[116] daclizumab (trade name Zenapax),[117] inosine,[118] or BG00012.[119] Other drugs in clinical trials have been designed specifically for MS, like fingolimod,[120] laquinimod,[121] or Neurovax.[122] Finally, there are also many basic investigations that in the future may be able to find new treatments. Examples of these are the studies trying to understand the influence of Chlamydophila pneumoniae or vitamin D in the origin of the disease,[123][124] or preliminary investigations on the use of helminthic therapy.[125]

Alternative treatments

Different alternative treatments are pursued by many patients, despite the paucity of supporting, comparable, replicated scientific study.

Clinical and experimental data suggest that certain dietary regimens, particularly those including polyunsaturated fatty acids, and vitamins might improve outcomes in people with multiple sclerosis.[126][127] Many diets have been proposed for treating the symptoms of the disease. Patients have reported a decrease in symptoms after long-term application of changes in diet; however, no controlled trials have been able to prove their efficacy.[128] Even if these diets are genuinely beneficial for people with MS, it is uncertain whether this is due to any special traits of the diets or that they are simply beneficial for whole body health. Two examples of such diets are the Swank Multiple Sclerosis Diet[129][130] and the Best Bet Diet.[131]

Herbal medicine is another source of alternative treatments. Many patients use medical marijuana to help alleviate symptoms; however, the results of experimental studies are scarce. At least one subgroup experiencing greater disability appears to have derived some symptomatic benefit.[132][133]

Hyperbaric oxygenation has been the subject of several small studies with heterogeneous results which, overall, do not support its use.[134]

The therapeutic practice of martial arts such as tai chi, relaxation disciplines such as yoga, or general exercise, seem to mitigate fatigue and improve quality of life.[135] Some studies also show benefits on physical variables, such as balance and strength or cardiovascular and respiratory function, but more investigation is needed as they are usually of low quality.[136]

Further reading

Clinical guidelines: clinical guidelines are documents with the aim of guiding decisions and criteria in specific areas of healthcare, as defined by an authoritative examination of current evidence (evidence-based medicine).

- The Royal College of Physicians (2004). Multiple Sclerosis. National clinical guideline for diagnosis and management in primary and secondary care. Salisbury, Wiltshire: Sarum ColourView Group. ISBN 1 86016 182 0.Free full text (2004-08-13). Retrieved on 2007-10-01.

- Multiple sclerosis. Understanding NICE guidance. Information for people with multiple sclerosis, their families and carers, and the public. London: National Institute of Clinical Excellence. 2003. ISBN 1-84257-445-0. Free full text (2003-11-26). Retrieved on 2007-10-25.

Notes and references

- ^ Methylprednisolone Oral. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-01.

- ^ Methylprednisolone Sodium Succinate Injection. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-01.

- ^ Sellebjerg F, Barnes D, Filippini G; et al. (2005). "EFNS guideline on treatment of multiple sclerosis relapses: report of an EFNS task force on treatment of multiple sclerosis relapses". Eur. J. Neurol. 12 (12): 939–46. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01352.x. PMID 16324087.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Goodin DS, Frohman EM, Garmany GP; et al. (2002). "Disease modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the MS Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines". Neurology. 58 (2): 169–78. PMID 11805241.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brusaferri F, Candelise L (2000). "Steroids for multiple sclerosis and optic neuritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials". J. Neurol. 247 (6): 435–42. PMID 10929272.

- ^ Dovio A, Perazzolo L, Osella G; et al. (2004). "Immediate fall of bone formation and transient increase of bone resorption in the course of high-dose, short-term glucocorticoid therapy in young patients with multiple sclerosis". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89 (10): 4923–8. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0164. PMID 15472186.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Uttner I, Müller S, Zinser C; et al. (2005). "Reversible impaired memory induced by pulsed methylprednisolone in patients with MS". Neurology. 64 (11): 1971–3. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000163804.94163.91. PMID 15955958.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Filippini G, Brusaferri F, Sibley WA; et al. (2000). "Corticosteroids or ACTH for acute exacerbations in multiple sclerosis". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (4): CD001331. PMID 11034713.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Miller D, Barkhof F, Montalban X, Thompson A, Filippi M (2005). "Clinically isolated syndromes suggestive of multiple sclerosis, part I: natural history, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and prognosis". Lancet neurology. 4 (5): 281–8. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70071-5. PMID 15847841.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jacobs LD, Beck RW, Simon JH; et al. (2000). "Intramuscular interferon beta-1a therapy initiated during a first demyelinating event in multiple sclerosis. CHAMPS Study Group". N Engl J Med. 343 (13): 898–904. PMID 11006365.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Comi G, Filippi M, Barkhof F; et al. (2001). "Effect of early interferon treatment on conversion to definite multiple sclerosis: a randomised study". Lancet. 357 (9268): 1576–82. PMID 11377645.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kappos L, Freedman MS, Polman CH; et al. (2007). "Effect of early versus delayed interferon beta-1b treatment on disability after a first clinical event suggestive of multiple sclerosis: a 3-year follow-up analysis of the BENEFIT study". Lancet. 370 (9585): 389–97. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61194-5. PMID 17679016.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Interferon beta-1a Intramuscular Injection. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2006-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ a b Interferon beta-1a Subcutaneous Injection. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2004-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ a b Interferon Beta-1b Injection. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2005-07-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ a b Glatiramer injection. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-07-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Ziemssen T, Schrempf W (2007). "Glatiramer acetate: mechanisms of action in multiple sclerosis". Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 79: 537–70. doi:10.1016/S0074-7742(07)79024-4. PMID 17531858.

- ^ a b Natalizumab Injection. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2006-10-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Ruggieri M, Avolio C, Livrea P, Trojano M (2007). "Glatiramer acetate in multiple sclerosis: a review". CNS Drug Rev. 13 (2): 178–91. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2007.00010.x. PMID 17627671.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Munari L, Lovati R, Boiko A (2004). "Therapy with glatiramer acetate for multiple sclerosis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD004678. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004678. PMID 14974077.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "pmid14974077" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Rice GP, Incorvaia B, Munari L; et al. (2001). "Interferon in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD002002. PMID 11687131.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Martinelli Boneschi F, Rovaris M, Capra R, Comi G (2005). "Mitoxantrone for multiple sclerosis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD002127. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002127.pub2. PMID 16235298.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "pmid16235298" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Fernández O, Fernández V, Mayorga C; et al. (2005). "HLA class II and response to interferon-beta in multiple sclerosis". Acta Neurol. Scand. 112 (6): 391–4. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2005.00415.x. PMID 16281922.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Johnson KP (2007). "Control of multiple sclerosis relapses with immunomodulating agents". J. Neurol. Sci. 256 Suppl 1: S23–8. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2007.01.060. PMID 17350652.

- ^ Gonsette RE (2007). "Compared benefit of approved and experimental immunosuppressive therapeutic approaches in multiple sclerosis". Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 8 (8): 1103–16. doi:10.1517/14656566.8.8.1103. PMID 17516874.

- ^ Murray TJ (2006). "The cardiac effects of mitoxantrone: do the benefits in multiple sclerosis outweigh the risks?". Expert opinion on drug safety. 5 (2): 265–74. doi:10.1517/14740338.5.2.265. PMID 16503747.

- ^ Should I have disease-modifying therapy for multiple sclerosis? Peace Health (2006-03-23). Retrieved on 2007-10-23.

- ^ McCormack PL, Scott LJ (2004). "Interferon-beta-1b: a review of its use in relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis". CNS drugs. 18 (8): 521–46. PMID 15182221.

- ^ Riluzole. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Azathioprine. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2004-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Methotrexate. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2006-10-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Cladribine. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Cyclophosphamide. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Leary SM, Thompson AJ (2005). "Primary progressive multiple sclerosis: current and future treatment options". CNS drugs. 19 (5): 369–76. PMID 15907149.

- ^ Sládková T, Kostolanský F (2006). "The role of cytokines in the immune response to influenza A virus infection". Acta Virol. 50 (3): 151–62. PMID 17131933.

- ^ Acetaminophen. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2007-07-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Ibuprofen. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2007-03-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Naproxen. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2006-01-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Betaseron [package insert]. Montville, NJ: Berlex Inc; 2003

- ^ Rebif [package insert]. Rockland, MA: Serono Inc; 2005.

- ^ Avonex [package insert]. Cambridge, MA: Biogen Inc; 2003

- ^ Durelli L, Ricci A (2004). "Anti-interferon antibodies in multiple sclerosis. Molecular basis and their impact on clinical efficacy". Front. Biosci. 9: 2192–204. PMID 15353281.

- ^ Fox EJ (2006). "Management of worsening multiple sclerosis with mitoxantrone: a review". Clinical therapeutics. 28 (4): 461–74. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.04.013. PMID 16750460.

- ^ Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Tyler KL (2005). "Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy complicating treatment with natalizumab and interferon beta-1a for multiple sclerosis". N Engl J Med. 353 (4): 369–74. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051782. PMID 15947079. Free full text with registration

- ^ Langer-Gould A, Atlas SW, Green AJ, Bollen AW, Pelletier D (2005). "Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with natalizumab". N Engl J Med. 353 (4): 375–81. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051847. PMID 15947078.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Free full text with registration - ^ Kappos L, Bates D, Hartung HP; et al. (2007). "Natalizumab treatment for multiple sclerosis: recommendations for patient selection and monitoring". Lancet neurology. 6 (5): 431–41. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70078-9. PMID 17434098.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kesselring J, Beer S (2005). "Symptomatic therapy and neurorehabilitation in multiple sclerosis". Lancet neurology. 4 (10): 643–52. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70193-9. PMID 16168933.

- ^ Di Fabio RP, Soderberg J, Choi T, Hansen CR, Schapiro RT (1998). "Extended outpatient rehabilitation: its influence on symptom frequency, fatigue, and functional status for persons with progressive multiple sclerosis". Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 79 (2): 141–6. PMID 9473994.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Solari A, Filippini G, Gasco P; et al. (1999). "Physical rehabilitation has a positive effect on disability in multiple sclerosis patients". Neurology. 52 (1): 57–62. PMID 9921849.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care for stroke. Stroke Unit Trialists' Collaboration". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (2): CD000197. 2000. PMID 10796318.

- ^ Turner-Stokes L, Disler PB, Nair A, Wade DT (2005). "Multi-disciplinary rehabilitation for acquired brain injury in adults of working age". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD004170. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004170.pub2. PMID 16034923.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g The Royal College of Physicians (2004). Multiple Sclerosis. National clinical guideline for diagnosis and management in primary and secondary care. Salisbury, Wiltshire: Sarum ColourView Group. ISBN 1 86016 182 0.Free full text (2004-08-13). Retrieved on 2007-10-01.

- ^ Heesen C, Romberg A, Gold S, Schulz KH (2006). "Physical exercise in multiple sclerosis: supportive care or a putative disease-modifying treatment". Expert review of neurotherapeutics. 6 (3): 347–55. doi:10.1586/14737175.6.3.347. PMID 16533139.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rietberg MB, Brooks D, Uitdehaag BM, Kwakkel G (2005). "Exercise therapy for multiple sclerosis". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD003980. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003980.pub2. PMID 15674920.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Merson RM, Rolnick MI (1998). "Speech-language pathology and dysphagia in multiple sclerosis". Physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America. 9 (3): 631–41. PMID 9894114.

- ^ Ghaffar O, Feinstein A (2007). "The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: a review of recent developments". Curr Opin Psychiatry. 20 (3): 278–85. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3280eb10d7. PMID 17415083.

- ^ Benedict RH, Bobholz JH (2007). "Multiple sclerosis". Seminars in neurology. 27 (1): 78–85. doi:10.1055/s-2006-956758. PMID 17226744.

- ^ a b Steultjens EM, Dekker J, Bouter LM, Leemrijse CJ, van den Ende CH (2005). "Evidence of the efficacy of occupational therapy in different conditions: an overview of systematic reviews". Clinical rehabilitation. 19 (3): 247–54. PMID 15859525.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baker NA, Tickle-Degnen L (2001). "The effectiveness of physical, psychological, and functional interventions in treating clients with multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis". The American journal of occupational therapy. : official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association. 55 (3): 324–31. PMID 11723974.

- ^ Steultjens EM, Dekker J, Bouter LM, Cardol M, Van de Nes JC, Van den Ende CH (2003). "Occupational therapy for multiple sclerosis". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD003608. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003608. PMID 12917976.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kurtzke JF (1983). "Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS)". Neurology. 33 (11): 1444–52. PMID 6685237.

- ^ Ayuso-Peralta L, de Andrés C (2002). "[Symptomatic treatment of multiple sclerosis]". Revista de neurologia (in Spanish; Castilian). 35 (12): 1141–53. PMID 12497297.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Alfuzosin. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2007-03-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Trospium. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2005-01-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Flavoxate. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Bosma R, Wynia K, Havlíková E, De Keyser J, Middel B (2005). "Efficacy of desmopressin in patients with multiple sclerosis suffering from bladder dysfunction: a meta-analysis". Acta Neurol. Scand. 112 (1): 15. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2005.00431.x. PMID 15932348.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Desmopressin. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Frances M Diro (2006-10-11). Urological Management in Neurological Disease. eMedicine. WebMD. Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ DasGupta R, Fowler CJ (2003). "Bladder, bowel and sexual dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: management strategies". Drugs. 63 (2): 153–66. PMID 12515563.

- ^ Diaz-Olavarrieta C, Cummings JL, Velazquez J, Garcia de la Cadena C (1999). "Neuropsychiatric manifestations of multiple sclerosis". The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 11 (1): 51–7. PMID 9990556.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gill D, Hatcher S (2007). "WITHDRAWN: Antidepressants for depression in medical illness". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD001312. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001312.pub2. PMID 17636666.

- ^ Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Mayo Clinic (2006-12-08). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Finger S (1998). "A happy state of mind: a history of mild elation, denial of disability, optimism, and laughing in multiple sclerosis". Arch. Neurol. 55 (2): 241–50. PMID 9482369.

- ^ Fishman I, Benedict RH, Bakshi R, Priore R, Weinstock-Guttman B (2004). "Construct validity and frequency of euphoria sclerotica in multiple sclerosis". The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 16 (3): 350–6. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.16.3.350. PMID 15377743.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rao SM (1986). "Neuropsychology of multiple sclerosis: a critical review". Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology: official journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 8 (5): 503–42. PMID 3805250.

- ^ Donepezil. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2007-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Christodoulou C, Melville P, Scherl W, Macallister W, Elkins L, Krupp L (2006). "Effects of donepezil on memory and cognition in multiple sclerosis". J Neurol Sci. 245 (1–2): 127–36. PMID 16626752.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Porcel J, Montalban X (2006). "Anticholinesterasics in the treatment of cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis". J Neurol Sci. 245 (1–2): 177–81. PMID 16674980.

- ^ Mohr DC, Boudewyn AC, Goodkin DE, Bostrom A, Epstein L (2001). "Comparative outcomes for individual cognitive-behavior therapy, supportive-expressive group psychotherapy, and sertraline for the treatment of depression in multiple sclerosis". Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 69 (6): 942–9. PMID 11777121.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Benedict RH, Shapiro A, Priore R, Miller C, Munschauer F, Jacobs L (2000). "Neuropsychological counseling improves social behavior in cognitively-impaired multiple sclerosis patients". Mult Scler. 6 (6): 391–6. PMID 11212135.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thomas PW, Thomas S, Hillier C, Galvin K, Baker R (2006). "Psychological interventions for multiple sclerosis". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD004431. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004431.pub2. PMID 16437487.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Amato MP, Zipoli V (2003). "Clinical management of cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: a review of current evidence". International MS journal / MS Forum. 10 (3): 72–83. PMID 14561373.

- ^ Bath PM, Bath FJ, Smithard DG (2000). "Interventions for dysphagia in acute stroke". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (2): CD000323. PMID 10796343.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bakshi R (2003). "Fatigue associated with multiple sclerosis: diagnosis, impact and management". Mult. Scler. 9 (3): 219–27. PMID 12814166.

- ^ Mohr DC, Hart SL, Goldberg A (2003). "Effects of treatment for depression on fatigue in multiple sclerosis". Psychosomatic medicine. 65 (4): 542–7. PMID 12883103.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pucci E, Branãs P, D'Amico R, Giuliani G, Solari A, Taus C (2007). "Amantadine for fatigue in multiple sclerosis". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD002818. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002818.pub2. PMID 17253480.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Amantadine. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-10-07.

- ^ Weinshenker BG, Penman M, Bass B, Ebers GC, Rice GP (1992). "A double-blind, randomized, crossover trial of pemoline in fatigue associated with multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 42 (8): 1468–71. PMID 1641137.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pemoline. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2006-01-01). Retrieved on 2007-10-07.

- ^ Mathiowetz VG, Finlayson ML, Matuska KM, Chen HY, Luo P (2005). "Randomized controlled trial of an energy conservation course for persons with multiple sclerosis". Mult Scler. 11 (5): 592–601. PMID 16193899.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Matuska K, Mathiowetz V, Finlayson M (2007). "Use and perceived effectiveness of energy conservation strategies for managing multiple sclerosis fatigue". The American journal of occupational therapy. : official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association. 61 (1): 62–9. PMID 17302106.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kerns RD, Kassirer M, Otis J (2002). "Pain in multiple sclerosis: a biopsychosocial perspective". Journal of rehabilitation research and development. 39 (2): 225–32. PMID 12051466.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Carbamazepine. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2007-05-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Phenytoin. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Brisman R (1987). "Trigeminal neuralgia and multiple sclerosis". Arch. Neurol. 44 (4): 379–81. PMID 3493757.

- ^ Bayer DB, Stenger TG (1979). "Trigeminal neuralgia: an overview". Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 48 (5): 393–9. PMID 226915.

- ^ Clonazepam. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Amitriptyline. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2007-08-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Moulin DE, Foley KM, Ebers GC (1988). "Pain syndromes in multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 38 (12): 1830–4. PMID 2973568.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Iskedjian M, Bereza B, Gordon A, Piwko C, Einarson TR (2007). "Meta-analysis of cannabis based treatments for neuropathic and multiple sclerosis-related pain". Current medical research and opinion. 23 (1): 17–24. doi:10.1185/030079906X158066. PMID 17257464.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Perras C (2005). "Sativex for the management of multiple sclerosis symptoms". Issues in emerging health technologies (72): 1–4. PMID 16317825.

- ^ Wade DT, Makela PM, House H, Bateman C, Robson P (2006). "Long-term use of a cannabis-based medicine in the treatment of spasticity and other symptoms in multiple sclerosis". Mult. Scler. 12 (5): 639–45. PMID 17086911.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cardini RG, Crippa AC, Cattaneo D (2000). "Update on multiple sclerosis rehabilitation". J. Neurovirol. 6 Suppl 2: S179–85. PMID 10871810.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baclofen oral. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-10-17.

- ^ Dantrolene oral. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-10-17.

- ^ Diazepam. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2005-07-01). Retrieved on 2007-10-17.

- ^ Tizanidine. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2005-07-01). Retrieved on 2007-10-17.

- ^ Beard S, Hunn A, Wight J (2003). "Treatments for spasticity and pain in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review". Health technology assessment (Winchester, England). 7 (40): iii, ix–x, 1–111. PMID 14636486.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Paisley S, Beard S, Hunn A, Wight J (2002). "Clinical effectiveness of oral treatments for spasticity in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review". Mult. Scler. 8 (4): 319–29. PMID 12166503.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Becker WJ, Harris CJ, Long ML, Ablett DP, Klein GM, DeForge DA (1995). "Long-term intrathecal baclofen therapy in patients with intractable spasticity". The Canadian journal of neurological sciences. Le journal canadien des sciences neurologiques. 22 (3): 208–17. PMID 8529173.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Leigh RJ, Averbuch-Heller L, Tomsak RL, Remler BF, Yaniglos SS, Dell'Osso LF (1994). "Treatment of abnormal eye movements that impair vision: strategies based on current concepts of physiology and pharmacology". Ann. Neurol. 36 (2): 129–41. PMID 8053648.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Starck M, Albrecht H, Pöllmann W, Straube A, Dieterich M (1997). "Drug therapy for acquired pendular nystagmus in multiple sclerosis". J. Neurol. 244 (1): 9–16. PMID 9007739.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Menon GJ, Thaller VT (2002). "Therapeutic external ophthalmoplegia with bilateral retrobulbar botulinum toxin- an effective treatment for acquired nystagmus with oscillopsia". Eye (London, England). 16 (6): 804–6. PMID 12439689.

- ^ Jain S, Proudlock F, Constantinescu CS, Gottlob I (2002). "Combined pharmacologic and surgical approach to acquired nystagmus due to multiple sclerosis". Am. J. Ophthalmol. 134 (5): 780–2. PMID 12429265.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ United Kingdom early Mitoxantrone Copaxone trial. Onyx Healthcare (2006-01-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Genzyme and Bayer HealthCare Announce Detailed Interim Two-Year Alemtuzumab in Multiple Sclerosis Data Presented at AAN. Genzyme (2007-02-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Daclizumab. PDL Biopharma (2006-01-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis Using Over the Counter Inosine. ClinicalTrials.gov (2006-03-16). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Efficacy and Safety of BG00012 in Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis. ClinicalTrials.gov (2007-09-01). Retrieved on 2007-11-12.

- ^ Efficacy and Safety of Fingolimod in Patients With Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis. ClinicalTrials.gov (2006-02-09). Retrieved on 2007-09-02.

- ^ Polman C, Barkhof F, Sandberg-Wollheim M, Linde A, Nordle O, Nederman T (2005). "Treatment with laquinimod reduces development of active MRI lesions in relapsing MS". Neurology. 64 (6): 987–91. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000154520.48391.69. PMID 15781813.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Darlington CL (2005). "Technology evaluation: NeuroVax, Immune Response Corp". Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 7 (6): 598–603. PMID 16370383.

- ^ Sriram S, Yao SY, Stratton C, Moses H, Narayana PA, Wolinsky JS (2005). "Pilot study to examine the effect of antibiotic therapy on MRI outcomes in RRMS". J. Neurol. Sci. 234 (1–2): 87–91. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2005.03.042. PMID 15935383.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Munger KL, Zhang SM, O'Reilly E; et al. (2004). "Vitamin D intake and incidence of multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 62 (1): 60–5. PMID 14718698.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Correale J, Farez M. (2007). "Association between parasite infection and immune responses in multiple sclerosis". Annals of Neurology. 61 (2): 97–108. PMID 17230481.

- ^ Schreibelt G, Musters RJ, Reijerkerk A; et al. (2006). "Lipoic acid affects cellular migration into the central nervous system and stabilizes blood-brain barrier integrity". J. Immunol. 177 (4): 2630–7. PMID 16888025.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ van Meeteren ME, Teunissen CE, Dijkstra CD, van Tol EA (2005). "Antioxidants and polyunsaturated fatty acids in multiple sclerosis". European journal of clinical nutrition. 59 (12): 1347–61. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602255. PMID 16118655.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Farinotti M, Simi S, Di Pietrantonj C; et al. (2007). "Dietary interventions for multiple sclerosis". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD004192. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004192.pub2. PMID 17253500.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Swank RL (1991). "Multiple sclerosis: fat-oil relationship". Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.). 7 (5): 368–76. PMID 1804476.

- ^ Swank RL, Goodwin J (2003). "Review of MS patient survival on a Swank low saturated fat diet". Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.). 19 (2): 161–2. PMID 12591551.

- ^ >Direct-MS Society - Clinical trials proposal and description Direct-MS. Retrieved on 2007-11-08.

- ^ Chong MS, Wolff K, Wise K, Tanton C, Winstock A, Silber E (2006). "Cannabis use in patients with multiple sclerosis". Mult. Scler. 12 (5): 646–51. PMID 17086912.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zajicek JP, Sanders HP, Wright DE, Vickery PJ, Ingram WM, Reilly SM, Nunn AJ, Teare LJ, Fox PJ, Thompson AJ (2005). "Cannabinoids in multiple sclerosis (CAMS) study: safety and efficacy data for 12 months follow up". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 76 (12): 1664–9. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2005.070136. PMID 16291891.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bennett M, Heard R (2004). "Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for multiple sclerosis". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD003057. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003057.pub2. PMID 14974004.

- ^ Oken BS, Kishiyama S, Zajdel D; et al. (2004). "Randomized controlled trial of yoga and exercise in multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 62 (11): 2058–64. PMID 15184614.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wang C, Collet JP, Lau J (2004). "The effect of Tai Chi on health outcomes in patients with chronic conditions: a systematic review". Arch Intern Med. 164 (5): 493–501. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.5.493. PMID 15006825.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)