User:Adert-it/sandbox

Signs and synptoms[edit]

The spectrum of the sexual pathology is very broad: there can be cryptorchidism, deficits of androgens, smalltestes and small penis.[1][2][3][4] During adulthood there may be azoospermia.[5] Testes tend to be small at all ages[6][7][8] because of the underdevelopment both of the germ cells and the interstitial cells. Gynecomastia is common in individuals suffering from the Klinefelter syndrome.[9]

Unlike other syndromes due to X polisomy that present a higher prevalence of mental retardation, only 10% subjects with the Klinefelter syndrome has a mental retardation.[10] Cognitive problems are less pervasive and more selective. On the neurological side, the Klinefelter syndrome is associated with reduced language development, problems of expressiveness, anomie, dysarthria.[11][12][13][14][15] On the behavioural side there may be immaturity, little security, shyness.[16][17].

Neurological and behavioral development[edit]

General intelligence measured with the full scale IQ (FSIQ) shows that in males with Klinefelter syndrome this is within the limits. Even if the QI in children and adolescents affected by this syndrome tends to be lower than the reference groups[18][19][20][21], in adulthood there may not be no difference at all. On the other hand, there is often a mismatch between verbal IQ and the performance IQ. This mismatch was observed both in affected children and adults.[12][22][23][19][20][21].

Studies suggest that the main defect in the boys is verbal, and this becomes evident during school years. At the age of 7, the affected subject has moderate to severe problems with reading, words articulation, writing, while problems concerning math skills might appear a little later.[24] Approximately 50-75% of children with Klinefelter syndrome show certain learning difficulties[25] , and of these 60-86% requires special education.[19][15]

Adolescents suffering from this syndrome show reduced confidence in themselves, are reserved, have difficulties in containing impulsiveness and to accept rules.[4] These symptoms have long-term implications on sociability and school activities and may persist into adulthood. Difficulties to adapt to the social environment however does not mean a misfitness. The commitment to the school frequently helps the boy suffering from Klinefelter syndrome to overcome these behavioural problems.[26]

Other clinical and physical manifestations[edit]

Other possible somatic characteristics are: reduced cranial circumference, gynecomastia, little body hair, narrowshoulders and broad hips, weak muscles.[4][9] Additional symptoms include: risk of osteoporosis, autoimmune disorders of the thyroid and diabetes mellitus type 2.[27] There is a 69% increased risk to be admitted to a hospital, even before having received the diagnosis of Kleinefelter syndrome.[28] Some studies have associated the syndrome with a slightly greater average height and with a predisposition to overweight.[29][9].

Patients with KS are characterized by particular hormonal modifications. The values of the follicle-stimulating hormone,luteinizing hormone, anti-Müllerian hormone and inhibin B are normal in prepubertal, and becomes abnormal with years. A study of adult individuals suffering from the syndrome has detected low testosterone levels in 45% cases and 43.6 % subjects reported sexual dysfunctions.[29] The probability of developing cancer is specific of this disease, because some of these pathologies are closely related, such as tumors to primitive germ cells of themediastinum[30] and the cancer of the breast[31], while for others there seems to be a protection factor, such as prostate cancer.[32]. Using the absolute excess risk (AER) for 100,000 persons per year as statistical parameter, the result is that the mortalities from lung cancer (AER +23.7), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (AER +12.1) and breast cancer male (AER +9.3) are increased.[32]

The arrangement 48,XXXY is associated with short neck, epicanthus, clinodactyly, radio-ulnar synostosis and mental retardation from moderate to severe. Associated to the 49,XXXXY karyotype there is an increased incidence of congenital cardiac abnormalities, especially the Botallo's patent ductus arterious. Mental retardation is often serious. Skeletal abnormalities include radio-ulnar synostosis, valgus knee, chest excavated and clinodactyly.[33].

Fertility[edit]

47,XXY karyotype is found in about 3.1% of azoospermic males. Most of Klinefelter males are azoospermic and, in fact, the testicular biopsy reveals absence of germ line cells, hypertrophy of the Leydig cells and marked fibrosis of the seminiferous tubules.[34] In addition, theantiandrogen therapy, used in the treatment of the syndrome, affects fertility adversely.[35]

Pregnancy from natural conception with Klinefelter partner have been described[36], more frequently in cases of mosaicism. In case of residual spermatogenesis, assisted fertilization can give the chance to Klinefelter males to have children, but since the biopsy technique of testicular sperm extraction (TESE) is invasive, it is always necessary to consider any possible sign of a residual spermatogenesis beforehand. Spermatogonia and spermatozoa are more frequent in the young because the number of gametes decreases rapidly with age, but the administration of aromatase inhibitors and human chorionic gonadotropin to stimulate endogenous production of testicular testosterone increases the sperm counts.

Spermatozoa thus obtained show the presence of abnormal gametes, not euploid, from 7 to 20% (in 46,XY male this share is less than 1%).[34]

Causes[edit]

Physiologically, an individual is characterized by two sex chromosomes. A male with normal karyotype has one X chromosome and a Y chromosome that determines the male sex; a woman on the contrary has two X chromosomes. The causal factor of the Klinefelter syndrome is the presence of at least one extra X chromosome[37], which in males alters the specific levels of those hormones linked to sexual physiology, by acting as if it was a second X chromosome, in particular by reducing the level of testosterone. A male suffering from this disease has, in fact, a genetic configuration XXY, that presents both the normal male chromosomes XY and the feminine XX.

It is believed that the presence of an extra X chromosome is caused by a non-disjunction event during meiosis, which may happen both on the maternal and the paternal side. There are no protective factors to prevent that from happening.[38]

In the case that the extra X chromosome comes from paternal side, the event origins during meiosis I (gametogenesis). The non-disjunction event occurs when homologous chromosomes, in this case X and Y, are not able to separate as it should happen in spermatogenesis. This produces a sperm with an extra X chromosome and a normal Y chromosome. The subsequent fertilization of a normal female egg (X) produces an XXY type of offspring[39]. The XXY arrangement of chromosome is one of the most common genetic variations of the XY karyotype and occurs in about 1 in 500 live male births.[40]

Otherwise, if the extra chromosome comes from the maternal side, the non-disjunction occurs during meiosis II. This occurs when the chromatids in the feminine sex chromosome, in this case one of the two Xs, are unable to separate. As a result, a XX egg is created that, once fertilized with a Y sperm, generates a XXY offspring. It is believed that the maternal transmission is more frequent than paternal transmission.[39]. The advanced age of the mother is a predisposing factor even if to a very limited extent and significantly less than the importance that it can have for the Down's syndrome.[38]

In mammals with more than one X chromosome, the genes on all but one X chromosome are not expressed; this is known as X inactivation. This happens in XXY males as well as normal XX females.[41] However, in XXY males, a few genes located in the pseudoautosomal regions of their X chromosomes, have corresponding genes on their Y chromosome and are capable of being expressed.[42]

The first published report of a man with a 47,XXY karyotype was by Patricia A. Jacobs and Dr. J.A. Strong at Western General Hospital in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1959.[43] This karyotype was found in a 24-year-old man who had signs of Klinefelter syndrome. Dr. Jacobs described her discovery of this first reported human or mammalian chromosome aneuploidy in her 1981 William Allan Memorial Award address.[44]

Variants[edit]

All forms of the Klinefelter syndrome are characterized by extra X-chromosome in a male phenotype. However, there are some variations. The karyotype 48, XXYY occurs in 1 case every 18,000 -40,000 male births. This phenotype does not differ much from the most common (47,XXY) except fot the higher average height observed in adulthood. The 49,XXXXY variant is a rare polisomy which is found in about one out of every 85,000 live male births. This condition is generally recognized very early for the serious deficits that it involves, which are, among others: marked mental retardation, facial dismorphisms (short neck, separated eyes, large mouth and nose, strabismus and large ears), cryptorchidism, ambiguous genitalia and skeletal defects (kyphosis and scoliosis, coxa valga) and heart disease.[45] The first patient suffering from this variant was described by Fraccaro et. al in 1960.[46] From then until 2012 the literature has reported little more than 100 cases.[45]

The literature also reported some cases of karyotype 48,XXXY, 48,XXYY (incidence 1:18,000 -1:100,000 male births) characterised by less serious phenotypic frameworks if compared to 49,XXXXY but more severe if compared to the classic karyotype (physical deformities, deficits of learning and psychological disorders). There were also reported some very rare cases of variations that comprise the karyotypes: 49,XXXYY, 48,XYYY, 49,XYYYY, and 49,XXYY. All these implies dysmorphic appearance and strong mental retardation.[47][48]

Males with Klinefelter syndrome may present a mosaicism in karyotype of form 47,XXY/46,XY which involves various degrees of deficient spermatogenesis.[49] The mosaicism 47,XXY/46,XX adds to the phenotype the other clinical characteristics of the syndrome, but is found very rarely, about 10 cases were described in 2006.[50]

Genetics[edit]

As in women, the extra X-chromosome is randomly inactivated, a phenomenon called Lyonization. It is possible that the inactivation in a stem cell is then "inherited" from the population of descending cells but, overall, the individual is a mosaic: this means that, in principle, he can have half of the cells with inactivation of the maternal X and half with inactivation of the paternal X. In this sense, all studies carried out to assess the correlation of symptoms with a determined parental origin of the X chromosome are insubstantial.

XIST (X inactive specific transcript) is the gene involved in this process. It transcribes RNA expressed only from the inactivated chromosome and does not encode any proteins. It acts on the inactivation center of X (XIC, X inactivation center). XIST is not expressed in the normal male (46,XY). A priori, each of the two X chromosomes of the Klinefelter male have the same probability to be activated, but not all genes are silenced: 15% remains in biallelic duplicate.[51][8] These seem to the primary responsible of the syndrome's phenotype.

The X chromosome differs from autosomes with regard to some characteristics: short and fewer genes; low density and high degree of conservation of the genes (not of their order). The polysomal pattern, i.e. the number of X chromosomes in the individual's karyotype (45,X0, 47,XXY, 47,XXX, 48,XXXX, and so on), strongly correlates with the associated symptoms.[52] This has lead to assume[53] an active role of the X chromosome not only in the determination of the sex, but also in the neurological development, on brain functions and on the behaviour of the subjects, an observation confirmed by several studies.[54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62] The genes of the X chromosome are expressed during the early stages of spermatogenesis and on the skeletal muscles, in the ovaries, the placenta and the brain.[63][64]

Locus Xq11-12 is the seat of the RA gene, coding for the receptor of androgens, that is a nuclear receptor with a domain that selectively recognizes androgens. This domain is encoded by a highly polymorphic site of the first exon, in which there is a sequence rich in CAG triplet. Proteins with a short CAG expansion are very similar and sensitive to androgens.[65] Conversely, a long CAG expansion is little affine and, if repetition exceeds 40, a severe pathology arises, i.e. the spinobulbar atrophy (Kennedy type), with neuromuscular effects, marked primary hypogonadism and gynecomastia of variable degree. In Klinefelter males the RA with the shortest CAG expansion[66], i.e. the more active RA, is inactivated. Subjects show a lower production of androgens and have low-affinity receptors.

The length of the CAG expansion is so far the only parameter genetically identifiable that correlates directly with the large degree of phenotypic variability of the syndrome.

Diagnosis[edit]

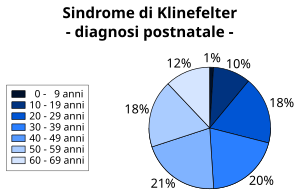

About 10% Klinefelter cases has prenatal diagnosis.[68] The first clinical features may appear in early childhood or, more frequently, during puberty, such as lack of secondary sexual characters, microrchidia and aspermatogenesis[69], while high stature as a symptom can hardly be diagnosed during puberty. Despite the presence of small testes, only a quarter of the affected male is recognized as Klinefelter at puberty[70][5]. and 25% received their diagnosis in late adulthood: about 64% affected individuals are not recognized as such.[71] There are no clear signs to suspect the syndrome: often the diagnosis is made accidentally as a result of examinations and medical visits for reasons not linked to the condition.[72]

The standard diagnostic method is the analysis of the chromosomes' karyogramme on lymphocytes. In the past, the observation of the Barr body was common practice as well.[73] To confirm the mosaicism, it is also possible to analyze the karyotype using dermal fibroblasts or testicular tissue.[74]

Other methods may be: research of high serum levels of gonadotropins (FSH and LH), presence of azoospermia, determination of the sex chromatin in oral swabs.[75] A Study carried out in 1994 proposed, as an alternative, to use polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as a faster diagnostic method. This is done by demonstrating the presence of RNA that carries the information of a gene, within the X chromosome, which serves as a marker for the inactivation of the second (and possibly more) X. This gene, called X-inactive-specific transcript (XIST), is transcribed only in the inactive X-chromosome.[75]

Differential diagnosis[edit]

The differential diagnosis for the Klinefleter syndrome can be made between two other genetic conditions: the fragile X syndrome (a mutation of the gene FMR1 on the X chromosome) and the Marfan syndrome (an autosomal dominant disease that affects the connective tissue). The cause of hypogonadism, peculiar of this syndrome, can be attributed to many other different medical conditions.

Some rare cases of individuals suffering from Down Syndrome also presented the 47/XXY defect.[76]

Treatment[edit]

The genetic variation is irreversible. For affected individuals who want a more masculine look, testosterone treatment is an option.[77] A study of adolescent patients treated with a subcutaneous implantation for the controlled release of this hormone has shown good results despite the need for constant monitoring.[78] Hormone therapy is also useful to prevent the onset of osteoporosis.

Often males who have gynecomastia and/or hypogonadism suffer from depression and/or social anxiety.[79] At least one study recommends psychological support for young people suffering from the Klinefelter syndrome in order to reduce their psycho-social deficits. The surgical mastectomy may be taken into account for both the psychological problems due to gynecomastia and to reduce the likelihood of developing breast cancer.[80]

The use of a behavioral therapy can mitigate any language disorders, difficulties at school and at the social level. An approach through occupational therapy is useful in Klinefleter children that show developmental verbal dyspraxia.[81]

Treatment against infertility[edit]

Until 1996, men with the typical Klinefelter karyotype were generally considered sterile. However, in 2010, more than 100 successful pregnancies have been reported using IVF technique (testicular sperm extraction or TESE) with surgically removed sperm material from men with Klinefelter syndrome.[82] A study carried out on the result of 54 TESE showed that the rate of recovery of the spermatozoa is 72% for each procedure and that 69% men had an adequate number of spermatozoa to realize the intracytoplasmatic sperm injection. 46% of all pregnancies obtained in this way have been successfully concluded and all children born had a normal karyotype.[83] Approximately 30% patients who undergo this procedure achieve these results.[84]

Sometimes seed is taken in adolescent age and cryopreserved to be able to attempt future procreation.[85].

Prognosis[edit]

Children with a XXY form differ little from healthy children. Although they can face problems during adolescence, often emotional and behavioural, and difficulties at school, most of them can achieve full independence from their families in adulthood. Some manage to obtain an university education and a normal, healthy life.[86]

The results of a study carried out on 87 Australian adults with the syndrome shows that those who have had a diagnosis and appropriate treatment from a very young age had a significant benefit with respect to those who had been diagnosed in adulthood.[87]

There seems to be a substantial decrease in life expectancy among individuals with the syndrome. Several studies have been made and the results are not definitive. A first work published in 1985 by Price et al. identified a greater mortality mainly due to diseases of the aortic valve, development of tumors and possible subarachnoid hemorrhages, reducing life expectancy by about 5 years[27] Following studies have reduced this estimate, associating to the condition an average 2.1 years reduction of life.[88] These data are not absolute and will need further testing.[89]

Following the diagnosis, no follow-up visit is necessary.[86].

Epidemiology[edit]

This syndrome, evenly spread in all ethnic groups, is the most common genetic disorder linked to heterosomes, with aprevalence of 1-2 subjects every 1000 males in the general population.[90][91][92][93] 3.1 % of infertile males are Klinefelter. The syndrome is also the main cause of male hypogonadism.[94] According to a meta-analysis, the prevalence of the syndrome has increased over the past decades; however, this does not appear to be correlated with the increase of the age of conception, as no increase was observed in the prevalence of other trisomies of sex chromosomes (XXX and XYY)[95].

Note[edit]

- ^ Laron Z, Hochman IH (1971). "Small testes in prepubetal boys with Klinefelter's syndrome". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 32 (5): 671–2. PMID 5577887.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Zeger MP, Zinn AR, Lahlou N, Ramos P, Kowal K, Samango-Sprouse C, Ross JL (2008). "Effect of ascertainment and genetic features on the phenotype of Klinefelter syndrome". J Pediatr. 152 (5): 716–22. PMID 18410780.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Salbenblattwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Stewart DA, Bailey JD, Netley CT, Park E (1990). "Growth, development, and behavioral outcome from mpmid-adolescence to adulthood in subjects with chromosome aneuplopmidy: the Toronto Study". Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 26 (4): 131–88. PMID 2090316.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Kamischke A, Baumgardt A, Horst J, Nieschlag E (2003). "Clinical and diagnostic features of patients with suspected Klinefelter syndrome". J Androl. 24 (1): 41–8. PMID 12514081.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Müller J, Skakkebaek NE, Ratcliffe SG (1995). "Quantified testicular histology in boys with sex chromosome abnormalities". Int J Androl. 18 (2): 57–62. PMID 7665210.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ratcliffe SG (1982). "The sexual development of boys with the chromosome constitution 47,XXY (Klinefelter's syndrome)". Clin Endocrinol Metab. 11 (3): 703–16. PMID 7139994.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Wikström AM, Raivio T, Hadziselimovic F, Wikström S, Tuuri T, Dunkel L (2004). "Klinefelter syndrome in adolescence: onset of puberty is associated with accelerated germ cell depletion". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 89 (5): 2263–70. PMID 15126551.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Mazzocco & Ross, p. 52 & mr.

- ^ "Incpmidenza sindromi genetiche causa di ritardo mentale". Retrieved 16 agosto 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Bender BG, Linden MG, Robinson A (1993). "Neuropsychological impairment in 42 adolescents with sex chromosome abnormalities". Am J Med Genet. 48 (3): 169–73. PMID 8291574.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Graham JM Jr, Bashir AS, Stark RE, Silbert A, Walzer S (1988). "Oral and written language abilities of XXY boys: implications for anticipatory gupmidance". Pediatrics. 81 (6): 795–806. PMID 3368277.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Netley C, Rovet J (1984). "Hemispheric lateralization in 47,XXY Klinefelter's syndrome boys". Brain Cogn. 3 (1): 10–8. PMID 6537238.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Nielsen J, Johnsen SG, Sørensen K (1980). "Follow-up 10 years later of 34 Klinefelter males with karyotype 47,XXY and 16 hypogonadal males with karyotype 46,XY". 10 (2): 345–52. PMID 7384334.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|riviista=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Walzer S (1985). "X chromosome abnormalities and cognitive development: implications for understanding normal human development". J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 26 (2): 177–84. PMID 3884639.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mandoki MW, Sumner GS, Hoffman RP, Riconda DL (1991). "A review of Klinefelter's syndrome in children and adolescents". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 30 (2): 167–72. PMID 2016217.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ratcliffe SG, Bancroft J, Axworthy D, McLaren W (1982). "Klinefelter's syndrome in adolescence". Arch Dis Child. 57 (1): 6–12. PMID 7065696.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ratcliffe S (1999). "Long-term outcome in children of sex chromosome abnormalities". Arch. Dis. Child. 80 (2): 192–5. PMC 1717826. PMID 10325742 PMID 10325742.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Bender BG, Puck MH, Salbenblatt JA, Robinson A (1986). "Dyslexia in 47,XXY boys pmidentified at birth". Behav. Genet. 16 (3): 343–54. PMID 3753369 PMID 3753369.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Rovet J, Netley C, Bailey J, Keenan M, Stewart D (1995). "Intelligence and achievement in children with extra X aneuplopmidy: a longitudinal perspective". Am. J. Med. Genet. 60 (5): 356–63. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320600503. PMID 8546146 PMID 8546146.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Walzer S, Bashir AS, Silbert AR (1990). "Cognitive and behavioral factors in the learning disabilities of 47,XXY and 47,XYY boys". Birth Defects Orig. Artic. Ser. 26 (4): 45–58. PMID 2090328 PMID 2090328.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Porter ME, Gardner HA, DeFeudis P, Endler NS (1988). "Verbal deficits in Klinefelter (XXY) adults living in the community". Clin. Genet. 33 (4): 246–53. PMID 3359682 PMID 3359682.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ratcliffe SG (1986). "Turner's syndrome". Arch. Dis. Child. 61 (9): 928. PMC 1778025. PMID 3767428 PMID 3767428.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Stewart DA, Netley CT, Bailey JD, Haka-Ikse K, Platt J, Holland W, Cripps M (1979). "Growth and development of children with X and Y chromosome aneuplopmidy: a prospective study". Birth Defects Orig. Artic. Ser. 15 (1): 75–114. PMID 444647 PMID 444647.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rovet J, Netley C, Keenan M, Bailey J, Stewart D (1996). "The psychoeducational profile of boys with Klinefelter syndrome". J Learn Disabil. 29 (2): 180–96. PMID 8820203 PMID 8820203.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Grace RJ (2004). "Klinefelter's syndrome: a late diagnosis". Lancet. 364 (9430): 284. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16679-8. PMID 15262107 PMID 15262107.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help) - ^ a b Price WH, Clayton JF, Wilson J, Collyer S, De Mey R (1985). "Causes of death in X chromatin positive males (Klinefelter's syndrome)". J Eppmidemiol Community Health. 39 (4): 330–6. PMC 1052467. PMID 4086964 PMID 4086964.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "pmid4086964" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Bojesen A, Juul S, Birkebaek NH, Gravholt CH (2006). "Morbpmidity in Klinefelter syndrome: a Danish register study based on hospital discharge diagnoses". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 91 (4): 1254–60. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-0697. PMID 16394093 PMID 16394093.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Pacenza N, Pasqualini T, Gottlieb S, Knoblovits P, Costanzo PR, Stewart Usher J, Rey RA, Martínez MP, Aszpis S (2012). "Clinical Presentation of Klinefelter's Syndrome: Differences According to Age". Int J Endocrinol. 2012: 324835. doi:10.1155/2012/324835. PMC 3265068. PMID 22291701 PMID 22291701.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Hainsworth JD, Greco FA (2001). "Germ cell neoplasms and other malignancies of the mediastinum". Cancer Treat. Res. 105: 303–25. PMID 11224992.

- ^ Swerdlow AJ, Hermon C, Jacobs PA, Alberman E, Beral V, Daker M, Fordyce A, Youings S (2001). "Mortality and cancer incpmidence in persons with numerical sex chromosome abnormalities: a cohort study". Ann. Hum. Genet. 65 (Pt 2): 177–88. doi:doi:10.1017/S0003480001008569. PMID 11427177.

{{cite journal}}: Check|doi=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Swerdlow AJ, Schoemaker MJ, Higgins CD, Wright AF, Jacobs PA (2005). "Cancer incpmidence and mortality in men with Klinefelter syndrome: a cohort study". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 97 (16): 1204–10. doi:10.1093/jnci/dji240. PMID 16106025 PMID 16106025.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Peet J,Weaver DD, Vance GH. 49, XXXXY: a distinct phenotype. Three new cases and revies. J Med Genet 1998; 35:420-424.

- ^ a b Ferlin A, Garolla A, Foresta C (2005). "Chromosome abnormalities in sperm of indivpmiduals with constitutional sex chromosomal abnormalities". Cytogenet. Gefirst1 Res. 111 (3–4): 310–6. doi:10.1159/000086905. PMID 16192710 PMID 16192710.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lanfranco F, Kamischke A, Zitzmann M, Nieschlag E (2004). "Klinefelter's syndrome". Lancet. 364 (9430): 273–83. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16678-6. PMID 15262106 PMID 15262106.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Forti G, Csilla K. La fertilità nella sindrome di Klinefelter: implicazioni pratiche e terapia. L’Endocrinologo 2006;7:32-9.

- ^ De Leo, Fasano, Ginelli, p. 585 & biogen

- ^ a b Casspmidy-Allanson, & ca.

- ^ a b De Leo, Fasano, Ginelli, p. 586 & biogen.

- ^ Verri A, Cremante A, Clerici F, Destefani V, Radicioni A (2010). "Klinefelter's syndrome and psychoneurologic function". Mol. Hum. Reprod. 16 (6): 425–33. doi:10.1093/molehr/gaq018. PMID 20197378 PMID 20197378.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chow, J; Yen, Z; Ziesche, S; Brown, C (2005). "Silencing of the mammalian X chromosome". Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 6: 69–92. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.6.080604.162350. PMID 16124854.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-name-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Blaschke, RJ; Rappold, G (2006). "The pseudoautosomal regions, SHOX and disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev". Jun;. 16 (3): 233–9. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2006.04.004. PMID 16650979.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-name-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Jacobs PA, Strong JA (1959). "A case of human intersexuality having a possible XXY sex-determining mechanism". Nature. 183 (4657): 302–3. doi:10.1038/183302a0. PMID 13632697.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Jacobs PA (1982). "The William Allan Memorial Award address: human population cytogenetics: the first twenty-five years". Am J Hum Genet. 34 (5): 689–98. PMC 1685430. PMID 6751075.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Patacchiola F, Sciarra A, Di Fonso A, D'Alfonso A, Carta G (2012). "49, XXXXY syndrome: an Italian child". J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 25 (1–2): 165–6. PMID 22570969 PMID 22570969.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fraccaro M, Kaijser K, Lindsten J (1960). "A child with 49 chromosomes". Lancet. 2 (7156): 899–902. PMID 13701146 PMID 13701146.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nelson, pp. 1350-1355 & nelson.

- ^ Linden MG, Bender BG, Robinson A (1995). "Sex chromosome tetrasomy and pentasomy". Pediatrics. 96 (4 Pt 1): 672–82. PMID 7567329 PMID 7567329.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help); Unknown parameter|lingua=ignored (|language=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lim AS, Fong Y, Yu SL (1999). "Estimates of sperm sex chromosome disomy and diplopmidy rates in a 47,XXY/46,XY mosaic Klinefelter patient". Hum. Genet. 104 (5): 405–9. PMID 10394932 PMID 10394932.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Velissariou V, Christopoulou S, Karadimas C, Pihos I, Kanaka-Gantenbein C, Kapranos N, Kallipolitis G, Hatzaki A (2006). "Rare XXY/XX mosaicism in a phenotypic male with Klinefelter syndrome: case report". Eur J Med Genet. 49 (4): 331–7. doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2005.09.001. PMID 16829354 PMID 16829354.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Aksglaede L, Wikström AM, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Dunkel L, Skakkebaek NE, Juul A (2006). "Natural history of seminiferous tubule degeneration in Klinefelter syndrome". Hum. Reprod. Update. 12 (1): 39–48. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmi039. PMID 16172111.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Davies W, Isles AR, Burgoyne PS, Wilkinson LS (2006). "X-linked imprinting: effects on brain and behaviour". Bioessays. 28 (1): 35–44. doi:10.1002/bies.20341. PMID 16369947.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Skuse DH, James RS, Bishop DV, Coppin B, Dalton P, Aamodt-Leeper G, Bacarese-Hamilton M, Creswell C, McGurk R, Jacobs PA (1997). "Evpmidence from Turner's syndrome of an imprinted X-linked locus affecting cognitive function". Nature. 387 (6634): 705–8. doi:10.1038/42706. PMID 9192895.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Reik W, Walter J (2001). "Genomic imprinting: parental influence on the gefirst1". Nat. Rev. Genet. 2 (1): 21–32. doi:10.1038/35047554. PMID 11253064.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kato Y, Sasaki H (2005). "Imprinting and looping: epigenetic marks control interactions between regulatory elements". Bioessays. 27 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1002/bies.20171. PMID 15612042.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Delaval K, Feil R (2004). "Epigenetic regulation of mammalian genomic imprinting". Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14 (2): 188–95. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2004.01.005. PMID 15196466.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Verona RI, Mann MR, Bartolomei MS (2003). "Genomic imprinting: intricacies of epigenetic regulation in clusters". Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 19: 237–59. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111401.092717. PMID 14570570.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Haig D (2004). "Genomic imprinting and kinship: how good is the evpmidence?". Annu. Rev. Genet. 38: 553–85. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.142741. PMID 15568986.

- ^ Weinhäusel A, Haas OA (2001). "Evaluation of the fragile X (FRAXA) syndrome with methylation-sensitive PCR". Hum. Genet. 108 (6): 450–8. PMID 11499669.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Davies W, Isles AR, Wilkinson LS (2005). "Imprinted gene expression in the brain". Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 29 (3): 421–30. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.11.007. PMID 15820547.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Davies W, Isles AR, Wilkinson LS (2001). "Imprinted genes and mental dysfunction". Ann. Med. 33 (6): 428–36. PMID 11585104.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zechner U, Wilda M, Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Vogel W, Fundele R, Hameister H (2001). "A high density of X-linked genes for general cognitive ability: a run-away process shaping human evolution?". Trends Genet. 17 (12): 697–701. PMID 11718922.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vallender EJ, Pearson NM, Lahn BT (2005). "The X chromosome: not just her brother's keeper". Nat. Genet. 37 (4): 343–5. doi:10.1038/ng0405-343. PMID 15800647.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ross MT, Grafham DV, Coffey AJ; et al. (2005). "The DNA sequence of the human X chromosome". Nature. 434 (7031): 325–37. doi:10.1038/nature03440. PMC 2665286. PMID 15772651.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zinn AR, Ramos P, Elder FF, Kowal K, Samango-Sprouse C, Ross JL (2005). "Androgen receptor CAGn repeat length influences phenotype of 47,XXY (Klinefelter) syndrome". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90 (9): 5041–6. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-0432. PMID 15956082.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zitzmann M, Depenbusch M, Gromoll J, Nieschlag E (2004). "X-chromosome inactivation patterns and androgen receptor functionality influence phenotype and social characteristics as well as pharmacogenetics of testosterone therapy in Klinefelter patients". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89 (12): 6208–17. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-1424. PMID 15579779.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bojesen A, Gravholt CH (2007). "Klinefelter syndrome in clinical practice". Nat Clin Pract Urol. 4 (4): 192–204. doi:10.1038/ncpuro0775. PMID 17415352.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Abramsky L, Chapple J (1997). "47,XXY (Klinefelter syndrome) and 47,XYY: estimated rates of and indication for postnatal diagnosis with implications for prenatal counselling". Prenat Diagn. 17 (4): 363–8. PMID 9160389.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Klinefelter HF Jr, Reifenstein EC Jr, Albright F. (1942). "Syndrome characterized by gynecomastia, aspermatogenesis without a-Leydigism and increased excretion of follicle-stimulating hormone". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2 (11): 615–624. doi:10.1210/jcem-2-11-615.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Bojesen2003was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Smyth CM, Bremner WJ (1998). "Klinefelter syndrome". Arch Intern Med. 158 (12): 1309–14. PMID 9645824.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|giorno=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Grzywa-Celińska A, Rymarz E, Mosiewicz J (2009). "[Diagnosis differential of Klinefelter's syndrome in a 24-year old male hospitalized with with sudden dyspnoea--case report]". Pol. Merkur. Lekarski (in Polacco). 27 (160): 331–3. PMID 19928664.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Kamischke A, Baumgardt A, Horst J, Nieschlag E (2003). "Clinical and diagnostic features of patients with suspected Klinefelter syndrome". J. Androl. 24 (1): 41–8. PMID 12514081.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kurková S, Zemanová Z, Hána V, Mayerová K, Pacovská K, Musilová J, Stĕpán J, Michalová K (1999). "[Molecular cytogenetic diagnosis of Klinefelter's syndrome in men more frequently detects sex chromosome mosaicism than classical cytogenetic methods]". Cas. Lek. Cesk. (in Czech). 138 (8): 235–8. PMID 10510542.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Kleinheinz A, Schulze W (1994). "Klinefelter's syndrome: new and rappmid diagnosis by PCR analysis of XIST gene expression". Andrologia. 26 (3): 127–9. PMID 8085664.

- ^ Sanz-Cortés M, Raga F, Cuesta A, Claramunt R, Bonilla-Musoles F (2006). "Prenatally detected double trisomy: Klinefelter and Down syndrome". Prenat. Diagn. 26 (11): 1078–80. doi:10.1002/pd.1561. PMID 16958145.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wikström AM, Dunkel L (2011). "Klinefelter syndrome". Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 25 (2): 239–50. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2010.09.006. PMID 21397196.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Moskovic DJ, Freundlich RE, Yazdani P, Lipshultz LI, Khera M (2012). "Subcutaneous implantable testosterone pellets overcome noncompliance in adolescents with klinefelter syndrome". J Androl. 33 (4): 570–3. PMID 21940986.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Simm PJ, Zacharin MR (2006). "The psychosocial impact of Klinefelter syndrome--a 10 year review". J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 19 (4): 499–505. PMID 16759035.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gabriele R, Borghese M, Conte M, Egpmidi F (2002). "Clinical-therapeutic features of gynecomastia". G Chir (in Italian). 23 (6–7): 250–2. PMID 12422780.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harold Chen. "Klinefelter Syndrome - Treatment". medscape.com. Retrieved 4 september 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Fullerton G, Hamilton M, Maheshwari A. (2010). "Should non-mosaic Klinefelter syndrome men be labelled as infertile in 2009?". Hum Reprod. 25 (3): 588–97. doi:10.1093/humrep/dep431. PMID 20085911.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schiff JD, Palermo GD, Veeck LL, Goldstein M, Rosenwaks Z, Schlegel PN (2005). "Success of testicular sperm extraction [corrected] and intracytoplasmic sperm injection in men with Klinefelter syndrome". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90 (11): 6263–7. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-2322. PMID 16131585.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vignozzi L, Corona G, Forti G, Jannini EA, Maggi M (2010). "Clinical and therapeutic aspects of Klinefelter's syndrome: sexual function". Mol. Hum. Reprod. 16 (6): 418–24. doi:10.1093/molehr/gaq022. PMID 20348547.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Damani MN, Mittal R, Oates RD (2001). "Testicular tissue extraction in a young male with 47,XXY Klinefelter's syndrome: potential strategy for preservation of fertility". Fertil. Steril. 76 (5): 1054–6.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|pmpmid=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Medscape - follow-up". Retrieved 19 august 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Herlihy AS, McLachlan RI, Gillam L, Cock ML, Collins V, Hallpmiday JL (2011). "The psychosocial impact of Klinefelter syndrome and factors influencing quality of life". Genet. Med. 13 (7): 632–42. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182136d19. PMID 21546843.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bojesen A, Juul S, Birkebaek N, Gravholt CH (2004). "Increased mortality in Klinefelter syndrome". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89 (8): 3830–4. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0777. PMID 15292313.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Swerdlow AJ, Higgins CD, Schoemaker MJ, Wright AF, Jacobs PA (2005). "Mortality in patients with Klinefelter syndrome in Britain: a cohort study". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90 (12): 6516–22. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-1077. PMID 16204366.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bojesen, A.; Juul, S.; Gravholt, CH. (2003). "Prenatal and postnatal prevalence of Klinefelter syndrome: a national registry study". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 88 (2): 622–6. PMID 12574191.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Jacobs, PA. (1979). "Recurrence risks for chromosome abnormalities". Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 15 (5C): 71–80. PMID 526617.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ MACLEAN, N.; HARNDEN, DG.; COURT BROWN, WM. (1961). "Abnormalities of sex chromosome constitution in newborn babies". Lancet. 2 (7199): 406–8. PMID 13764957.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Visootsak, J.; Aylstock, M.; Graham, JM. (2001). "Klinefelter syndrome and its variants: an update and review for the primary pediatrician". Clin Pediatr (Phila). 40 (12): 639–51. PMID 11771918.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Matlach, J.; Grehn, F.; Klink, T. (2012). "Klinefelter Syndrome Associated With Goniodysgenesis". J Glaucoma. doi:10.1097/IJG.0b013e31824477ef. PMID 22274665.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Morris, JK.; Alberman, E.; Scott, C.; Jacobs, P. (2008). "Is the prevalence of Klinefelter syndrome increasing?". Eur J Hum Genet. 16 (2): 163–70. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201956. PMID 18000523.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)