Victor/Victoria

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2016) |

| Victor/Victoria | |

|---|---|

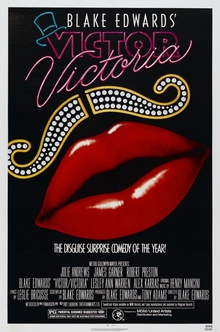

Theatrical release poster by John Alvin | |

| Directed by | Blake Edwards |

| Screenplay by | Blake Edwards |

| Story by | Hans Hoemburg |

| Based on | Victor and Victoria by Reinhold Schünzel |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Dick Bush |

| Edited by | Ralph E. Winters |

| Music by | Songs: Henry Mancini Leslie Bricusse (lyrics) Score: Henry Mancini |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates | |

Running time | 132 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $15 million[2] |

| Box office | $28.2 million |

Victor/Victoria is a 1982 musical comedy film written and directed by Blake Edwards and starring Julie Andrews, James Garner, Robert Preston, Lesley Ann Warren, Alex Karras, and John Rhys-Davies. The film was released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, produced by Tony Adams and scored by Henry Mancini, with lyrics by Leslie Bricusse. Victor/Victoria was adapted as a Broadway musical in 1995. The film was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won the Academy Award for Best Original Song Score or Adaptation Score. It is a remake of the 1933 German film Victor and Victoria.

Plot

[edit]In 1934 Paris, Carroll "Toddy" Todd, an aging gay performer at Club Chez Lui, sees Labisse, the owner, auditioning frail and impoverished soprano Victoria Grant. After her failed audition, Victoria returns to her hotel room to find herself about to be evicted, as she cannot pay her rent. That night, when hustler Richard, with whom Toddy is romantically involved, comes to Chez Lui as part of a straight foursome, Toddy incites a brawl resulting in damages and the police locking up whomever they can get their hands on. Labisse fires Toddy and bans him from the club. Walking home, Toddy spots Victoria in a restaurant. She invites him to join her. As both of them are poor, she plans to dump a cockroach in her salad to avoid paying, but it escapes and mayhem ensues.

The duo run through the rain to Toddy's, and he invites her to stay when she discovers the rain shrunk and damaged her decrepit clothing. The next morning Richard shows up to collect his things. Victoria, who is wearing his suit and hat, hides in Toddy's closet. When Richard opens the closet, she punches him, breaking his nose before kicking him out. Seeing this, Toddy is struck with the inspiration of passing Victoria off as a man and presenting her to successful talent agent Andre Cassell as a female impersonator.

Cassell accepts her as Count Victor Grazinski, a gay Polish impersonator and Toddy's new boyfriend. Cassell gets her a booking in a nightclub show and invites club owners to the opening. Among the guests are Chicago gangster King Marchand, his moll Norma Cassidy and bodyguard Mr. Bernstein, also known as Squash. Victoria performs "Le Jazz Hot" and becomes a hit. King is smitten, but is shocked when she "reveals" herself to be a man at the end of the act. King, however, is convinced that "Victor" is not a man because he insists that there's no way he could be attracted to another man.

After Norma attacks King during a quarrel, he sends her back to the United States. Determined to uncover the truth, King sneaks into Victoria and Toddy's suite and confirms his suspicion when he spies her getting into the bath. In Chicago, Norma, angry over being dumped, tells King's business partner Sal Andretti that King is having an affair with a man. King invites Victoria, Toddy and Cassell to Chez Lui. Another fight breaks out. Squash and Toddy are arrested, along with many of the club clientele, but King and Victoria escape. Once outside the club, King says he doesn't care if Victor is a man, and kisses him. Victoria admits she's not a man. King says he still doesn't care, and kisses her again.

Squash returns to the suite and catches him in bed with Victoria. King tries to explain, but then Squash reveals that he himself is gay. Victoria and King argue over whether or not the relationship could work and Victoria discovers that King is not really a gangster but someone who pretends to be to stay in the nightclub business. Both he and Victoria are pretending to be something they are not. Victoria returns to her room and finds Squash in bed with Toddy.

Meanwhile, Labisse hires private investigator Charles Bovin to tail Victor. Victoria and King attempt to live together, but keeping up her deception strains the relationship, and King eventually ends it.

At the same time that Victoria decides to give up the Victor persona to be with King, Sal arrives and demands that King transfer his share of the business to Sal for a fraction of what it is actually worth. Squash tells Victoria what is happening, and she shows Norma that she is really a woman, saving King's stake. That night at the club, Cassell tells Toddy and Victoria that Labisse lodged a police complaint against him and "Victor" for perpetrating a public fraud. After checking for himself, the inspector tells Labisse that the performer he saw in the room, after opening the door, is a man and that Labisse is an idiot.

Victoria joins King in the club as her real self. The announcer says that Victor will perform, but instead of Victoria, Toddy masquerades as "Victor". After an intentionally disastrous performance, Toddy claims that this is his last performance.

Cast

[edit]- Julie Andrews as Victoria Grant / Count Victor Grazinski

- James Garner as King Marchand

- Robert Preston as Carroll "Toddy" Todd

- Lesley Ann Warren as Norma Cassidy

- Alex Karras as "Squash" Bernstein

- John Rhys-Davies as Andre Cassell

- Graham Stark as waiter

- Peter Arne as Labisse

- Herb Tanney (credited as Sherloque Tanney) as Charles Bovin

- Michael Robbins as manager of Victoria's Hotel

- Norman Chancer as Sal Andratti

- David Gant as restaurant manager

- Maria Charles as Madame President

- Malcolm Jamieson as Richard Di Nardo

- Jay Benedict as Guy Langois

- Ina Skriver as Simone Kallisto

- Geoffrey Beevers as police inspector

- Norman Alden as man in hotel with shoes (uncredited)

- Doug Sheehan as Le Jazz Hot Dancer/Shady Dame from Seville a Dancing Matador (uncredited)

- Glen Murphy as boxer (uncredited)

Musical numbers

[edit]The vocal numbers in the film are presented as nightclub acts, with choreography by Paddy Stone. However, the lyrics or situations of some of the songs are calculated to relate to the unfolding drama. Thus, the two staged numbers "Le Jazz Hot" and "The Shady Dame from Seville" help to present Victoria as a female impersonator. The latter number is later reinterpreted by Toddy for diversionary purposes in the plot, and the cozy relationship of Toddy and Victoria is promoted by the song "You and Me", which is sung before the audience at the nightclub.[3]

- "Gay Paree" – Toddy

- "Le Jazz Hot!" – Victoria

- "The Shady Dame from Seville" – Victoria

- "You and Me" – Toddy, Victoria

- "Chicago, Illinois" – Norma

- "Crazy World" – Victoria

- "Finale/Shady Dame from Seville (Reprise)" – Toddy

Occasionally, Victoria and Toddy sing "Home on the Range" when they are in the hotel.

Production

[edit]The film's screenplay was adapted by Blake Edwards (Andrews' husband) from the 1933 German film Victor and Victoria written and directed by Reinhold Schünzel from an original story treatment by Hans Hoemburg. According to Edwards, the screenplay took only one month to write. Andrews watched the 1933 version to prepare for her role. The film had been planned as early as 1978 with Andrews to star alongside Peter Sellers, but Sellers died in 1980 while Andrews and Edwards were filming S.O.B. (1981), so Robert Preston was cast in the role of Toddy.

The costume worn by Andrews in the number "The Shady Dame from Seville" is in fact the same costume worn by Preston at the end of the film. It was made to fit Preston, and then, using a series of hooks and eyes at the back, it was drawn in tight to fit Andrews' shapely figure. Black silk ruffles were added to the bottom of the garment to hide the differences in height. The fabric is a black and brown crepe, with fine gold threads woven into it, that when lit appears to have an almost wet look about it.[4]

Release

[edit]Victor/Victoria was the opening night film at Filmex on March 16, 1982. It opened in New York, Los Angeles, and Toronto on March 19, 1982.[1]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave it 3 out of 4 stars and wrote: "Not only a funny movie, but, unexpectedly, a warm and friendly one."[5] Todd McCarthy of Variety called it "sparkling, ultra-sophisticated entertainment from Blake Edwards."[6]

Vincent Canby in the New York Times was enthusiastic: “Get ready, get set, and go—immediately—to the Ziegfeld Theater, where Blake Edwards today opens his chef d’oeuvre, his cockeyed, crowning achievement....It’s called ‘Victor/Victoria,' and it stars Julie Andrews, Robert Preston and James Garner, each giving the performances of his and her career in a marvelous fable about mistaken identity, sexual role-playing, love, innocence and sight gags....Although ‘Victor/Victoria’ preaches tolerance and understanding of homosexuality, and though it uses the word ‘gay’ in a way that I doubt was much used in 1934 Paris, even in the demimonde portrayed in this film, the roots of the comedy are as ancient as the use of masks and disguises in the theater....’Victor/Victoria’ is so good, so exhilarating, that the only depressing thing about it is the suspicion that Mr. Edwards is going to have a terrible time trying to top it.”[7]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 97% based on 33 reviews, with an average rating of 8/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "Driven by a fantastic lead turn from Julie Andrews, Blake Edwards' musical gender-bender is sharp, funny and all-round entertaining."[8] On Metacritic, it has a score of 84 out of 100 based on reviews from 12 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[9]

Accolades

[edit]In 2000, American Film Institute included the film in AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs (#76).[22]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Tied with Meryl Streep for Sophie's Choice.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Victor/Victoria at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- ^ Moses, Antoinette (Fall 1982). "British Production 1981". Sight & Sound. Vol. 51, no. 4. p. 258. ISSN 0037-4806.

- ^ "Victor/Victoria". AllMovie. Archived from the original on December 16, 2009. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ Stirling, Richard (2008). Julie Andrews: An Intimate Biography. Macmillan. pp. 272. ISBN 978-0-312-38025-0.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (October 23, 2004). "Victor/Victoria movie review & film summary (1982)". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on September 2, 2020. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (March 17, 1982). "Film Reviews: Victor/Victoria". Variety. Archived from the original on July 19, 2020. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ Canby, Vincent. “A Blake Edwards Farce.” New York Times, 19 March 1982, C8.

- ^ "Victor/Victoria". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on May 30, 2024. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ "Victor Victoria". Metacritic. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ "The 55th Academy Awards (1983) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on November 13, 2014. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ "NY Times: Victor/Victoria". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2010. Archived from the original on November 17, 2010. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ Oldham, Gabriella (2017). Blake Edwards: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781496815675. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ "Best Cinematography in Feature Film" (PDF). British Society of Cinematographers. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 4, 2021. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "The 1983 Caesars Ceremony". César Awards. Archived from the original on August 4, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Cronologia Dei Premi David Di Donatello". David di Donatello. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- ^ "Victor/Victoria". Golden Globe Awards. Archived from the original on September 23, 2021. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ "25th Annual GRAMMY Awards". Grammy Awards. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- ^ "KCFCC Award Winners – 1980-89". Kansas City Film Critics Circle. December 14, 2013. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ "1982 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ "1982 New York Film Critics Circle Awards". Mubi. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ "Awards Winners". wga.org. Writers Guild of America Awards. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs" (PDF). American Film Institute. 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 13, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

External links

[edit]- Victor/Victoria at IMDb

- Victor/Victoria at AllMovie

- Victor/Victoria at Box Office Mojo

- Victor/Victoria at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Victor/Victoria at the TCM Movie Database

- James Garner Interview on the Charlie Rose Show Archived 2008-01-03 at the Wayback Machine

- James Garner interview at Archive of American Television

- 1982 films

- 1980s American films

- 1980s British films

- 1980s English-language films

- 1980s musical comedy films

- 1980s romantic musical films

- 1980s sex comedy films

- 1982 LGBTQ-related films

- 1982 romantic comedy films

- American LGBTQ-related films

- American musical comedy films

- American remakes of German films

- American romantic comedy films

- American romantic musical films

- American sex comedy films

- Best Foreign Film César Award winners

- British LGBTQ-related films

- British musical comedy films

- British remakes of German films

- British romantic comedy films

- British romantic musical films

- British sex comedy films

- Casting controversies in film

- Comedy film remakes

- Compositions by Leslie Bricusse

- Cross-dressing in American films

- Cross-dressing in British films

- Drag (entertainment)-related films

- Fictional LGBTQ couples

- Films about trans men

- Films adapted into plays

- Films directed by Blake Edwards

- Films featuring a Best Musical or Comedy Actress Golden Globe winning performance

- Films scored by Henry Mancini

- Films set in 1934

- Films set in Paris

- Films set in the 1930s

- Films shot at Pinewood Studios

- Films that won the Best Original Score Academy Award

- Films with screenplays by Blake Edwards

- Gay-related films

- Homophobia in fiction

- LGBTQ-related controversies in film

- LGBTQ-related musical comedy films

- LGBTQ-related romantic comedy films

- LGBTQ-related sex comedy films

- Films about male bisexuality

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- Musical film remakes

- Romance film remakes

- Transgender-related films

- English-language sex comedy films

- English-language romantic comedy films

- English-language romantic musical films

- English-language musical comedy films