Western Front tactics, 1917

| Western Front | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War I | |||||||

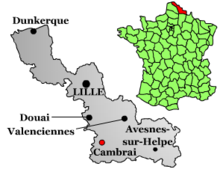

Map of the Western Front, 1917 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Ferdinand Foch from early 1918 | Helmuth von Moltke the Younger → Erich von Falkenhayn → Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff → Hindenburg and Wilhelm Groener | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 7,947,000 | 5,603,000 | ||||||

In 1917, during World War I, the armies on the Western Front continued to change their fighting methods, due to the consequences of increased firepower, more automatic weapons, decentralisation of authority and the integration of specialised branches, equipment and techniques into the traditional structures of infantry, artillery and cavalry. Tanks, railways, aircraft, lorries, chemicals, concrete and steel, photography, wireless and advances in medical science increased in importance in all of the armies, as did the influence of the material constraints of geography, climate, demography and economics. The armies encountered growing manpower shortages, caused by the need to replace the losses of 1916 and by the competing demands for labour by civilian industry and agriculture. Dwindling manpower was particularly marked in the French and German armies, which made considerable changes in their methods during the year, simultaneously to pursue military-strategic objectives and limit casualties.

The French returned to a strategy of decisive battle in the Nivelle Offensive in April, using methods pioneered at the Battle of Verdun in December 1916, to break through the German defences on the Western front and return to manoeuvre warfare (Bewegungskrieg) but ended the year recovering from the disastrous result. The German army attempted to avoid the high infantry losses of 1916 by withdrawing to new deeper and dispersed defences. Defence in depth was intended to nullify the growing material strength of the Allies, particularly in artillery and succeeded in slowing the growth of Anglo-French battlefield superiority. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) continued its evolution into a mass army, capable of imposing itself on a continental power, took on much of the military burden borne by the French and Russian armies since 1914 and left the German army resorting to expedients to counter the development of its increasingly skilful use of fire-power and technology. During 1917 the BEF also encountered the manpower shortages affecting the French and Germans and at the Battle of Cambrai in December, experienced its biggest German attack since 1915, as German reinforcements began to flow from the Eastern Front.

Background

Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff replaced Chief of the General Staff Erich von Falkenhayn at the end of August 1916, during "the most serious crisis of the war".[1] On 2 September the new leadership ordered a strict defensive at Verdun and the dispatch of forces from there to reinforce the Somme and Romanian fronts. Hindenburg and Ludendorff visited the Western front and held a meeting at Cambrai on 8 September with the army group and other commanders, at which the gravity of the situation in France and the grim prospects for the new year were debated. Hindenburg and Ludendorff had already announced a reconnaissance on 6 September for a new, shorter line behind the Noyon salient. On 15 September a defensive strategy was announced except for Romania and Generalfeldmarschall Rupprecht (commander of the northern army group on the Western front) was instructed to prepare a new line, Arras–St. Quentin–Laon–Aisne river. The new line across the base of the Noyon salient would be about 30 mi (48 km) shorter and was to be completed in three months. These defences were planned with the experience gained on the Somme, which showed a need for much greater defensive depth and many small shallow concrete Mannschafts-Eisenbeton-Unterstände (Mebu shelters), rather than elaborate entrenchments and deep dug-outs, which had become man-traps. Work began on 23 September; two trench lines about 200 yd (180 m) apart were dug as an outpost line (Sicherheitsbesatzung) and a main line of resistance (Hauptverteidigungslinie) on a reverse slope, (Hinterhangstellung) behind fields of barbed wire up to 100 yd (91 m) deep. Concrete machine-gun nests and Mebu shelters were built either side of the main line, with artillery observation posts built farther back to overlook it.[2]

On 31 August, Hindenburg and Ludendorff had begun the expansion of the army to 197 divisions and of munitions production in the Hindenburg Programme, necessary to meet demand after the vast expenditure of ammunition in 1916 (on the Somme in September, 5,725,440 field artillery shells and 1,302,000 heavy shells had been fired) and the anticipated increase in artillery use by the Allies in 1917.[3] It was intended that the new defensive positions would contain any Allied breakthrough and give the German army the choice of a deliberate withdrawal, to dislocate an expected Allied offensive in the new year.[4] Over the winter of 1916–1917, the wisdom of a deliberate withdrawal was debated and at a meeting on 19 December, called after the 15 December debacle during the Battle of Verdun, the possibility of a return to the offensive was also discussed. With a maximum of 21 divisions expected to be available by March 1917, a decisive success was considered impossible.[5] Ludendorff continued to vacillate but in the end, the manpower crisis and the prospect of releasing thirteen divisions by a withdrawal on the Western Front, to the new Siegfriedstellung (Hindenburg line), overcame his desire to avoid the tacit admission of defeat it represented. The Alberich Bewegung (Alberich manoeuvre) was ordered to begin on 16 March 1917, although a withdrawal of 3 mi (4.8 km) on a 15 mi (24 km) front had already been carried out from 22–23 February, in the salient between Bapaume and Arras, formed by the Allied advance on the Somme in 1916.[6][7] The local retirements had been caused by the renewal of pressure by the British Fifth Army, as soon as weather permitted in January 1917, which had advanced 5 mi (8.0 km) on a 4 mi (6.4 km) front up the Ancre valley.[8][9]

German defensive preparations, early 1917

Third OHL

On 29 August 1916, Hindenburg and Ludendorff had been appointed to the Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL supreme army command) of the German army, after the sacking of Falkenhayn, who had commanded the armies of Germany since September 1914. The new commanders, who became known as the Third OHL, had spent two years in command of Ober Ost, the German section of the Eastern Front. Hindenburg and Ludendorff had demanded reinforcements from Falkenhayn to fight a decisive campaign against Russia and intrigued against Falkenhayn over his refusals. Falkenhayn held that decisive military victory against Russia was impossible and that the Western Front was the main theatre of the war. Soon after taking over from Falkenhayn, Hindenburg and Ludendorff had no choice but to recognise the wisdom of Falkenhayn's judgement that the Western Front was decisive, despite the crisis in the east caused by the Brusilov Offensive (4 June – 20 September) and the Rumanian declaration of war on 28 August.[10]

Cambrai conference

On 8 September 1916, Hindenburg and Ludendorff held a conference at Cambrai with the chiefs of staff of the armies of the Westheer as part of a tour of inspection of the Western Front. Both men were dismayed at the nature of trench warfare that they found, in such contrast to the conditions on the Eastern Front and the dilapidated state of the Westheer. The Battle of Verdun and the Battle of the Somme had been extraordinarily costly and on the Somme, 122,908 German casualties had been suffered from 24 June to 28 August. The battle had required the use of 29 divisions and by September, one division a day had to be replaced by a fresh one. General Hermann von Kuhl the Chief of Staff of Heeresgruppe Deutscher Kronprinz (Army Group German Crown Prince) reported that conditions at Verdun were little better and that the recruit depots behind the army group front could supply only 50–60 percent of the casualty replacements needed. From July to August the Westheer had fired the equivalent of 587 trainloads of field gun shells, for the receipt of only 470 from Germany, creating a munitions shortage.[11][a]

The 1st Army on the north side of the Somme reported on 28 August that,

The complications of the entire battle lay only in part with the superiority in number of enemy divisions (12 or 13 enemy against eight German on the battlefield) for our infantry feel completely the superiority of the English and French in close battle. The most difficult factor in the battle is the enemy's superiority in munitions. This allows their artillery, which is excellently supported by aircraft, to level our trenches and to wear down our infantry systematically.... The destruction of our positions is so thorough that our foremost line merely consists of occupied shell-holes.

It was known in Germany that the British had introduced conscription on 27 January 1916 and that despite the huge losses on the Somme, there would be no shortage of reinforcements. At the end of August, German military intelligence calculated that of the 58 British divisions in France, 18 were fresh. The French manpower situation was not as buoyant but by combing out rear areas and recruiting more troops from the colonies, the French could replace losses, until the 1918 conscription class became available in the summer of 1917. Of the 110 French divisions in France, 16 were in reserve and another 10–11 divisions could be obtained by swapping tired units for fresh ones on quiet parts of the front.[12]

Ludendorff admitted privately to Kuhl that victory appeared impossible, who wrote in his diary that

I spoke...with Ludendorff alone (about the overall situation). We were in agreement that a large-scale, positive outcome is now no longer possible. We can only hold on and take the best opportunity for peace. We made too many serious errors this year.

— Kuhl, Kriegstagebuch (diary), 8 September 1916[13]

On 29 August, Hindenburg and Ludendorff reorganised the army groups on the Western Front, by incorporating all but the 4th Army in Flanders into the army group structure on the active part of the Western Front. The administrative reorganisation eased the distribution of men and equipment but made no difference to the lack of numbers and the growing Franco-British superiority in weapons and ammunition. New divisions were needed and the manpower for them and the replacement of the losses of 1916 had to be found. The superiority in manpower enjoyed by the Entente and its allies could not be surpassed but Hindenburg and Ludendorff drew on ideas from Oberstleutnant (Lieutenant-Colonel) Max Bauer of the Operations Section at OHL HQ in Mézières, for a further industrial mobilisation, to equip the army for the materialschlacht (battle of equipment/battle of attrition) being inflicted on it in France, which would only intensify in 1917.[14]

Hindenburg Programme

The new programme was intended to create a trebling of artillery and machine-gun output and a doubling of munitions and trench mortar production. Expansion of the army and output of war materials caused increased competition for manpower between the army and industry. In early 1916, the German army had 900,000 men in recruit depots and another 300,000 due in March when the 1897 class of conscripts was called up. The army was so flush with men that plans were made to demobilise older Landwehr classes and in the summer, Falkenhayn ordered the raising of another 18 divisions, for an army of 175 divisions. The costly battles at Verdun and the Somme had been much more demanding on German divisions and they had to be relieved after only a few days in the front line, lasting about 14 days on the Somme. A larger number of divisions might reduce the strain on the Westheer and realise a surplus for offensives on other fronts. Hindenburg and Ludendorff ordered the creation of another 22 divisions, to reach 179 divisions by early 1917.[15]

The men for the divisions created by Falkenhayn had come from reducing square divisions with four infantry regiments to triangular divisions with three regiments, rather than a net increase in the number of men in the army. Troops for the extra divisions of the expansion ordered by Hindenburg and Ludendorff could be found by combing out rear-area units but most would have to be drawn from the pool of replacements, which had been depleted by the losses of 1916 and although new classes of conscripts would top up the pool, casualty replacement would become much more difficult once the pool had to maintain a larger number of divisions. By calling up the 1898 class of recruits early in November 1916, the pool was increased to 763,000 men in February 1917 but the larger army would become a wasting asset. Ernst von Wrisberg, Abteilungschef of the kaiserlicher Oberst und Landsknechtsführer (head of the Prussian Ministry of War section responsible for raising new units), had grave doubts about the wisdom of the increase in the expansion of the army but was over-ruled by Ludendorff.[15]

The German army had begun 1916 equally well-provided for in artillery and ammunition, massing 8.5 million field and 2.7 million heavy artillery shells for the beginning of the Battle of Verdun but four million rounds were fired in the first fortnight and the 5th Army needed about 34 ammunition trains a day to continue the battle. The Battle of the Somme further reduced the German reserve of ammunition and when the infantry was forced out of the front position, the need for Sperrfeuer (barrage fire), to compensate for the lack of obstacles, increased. Before the war, Germany had imported nitrates for propellant manufacture and only the discovery of the Haber process, to synthesise nitrates from atmospheric nitrogen, enabled Germany to continue the war; developing the Haber process and building factories to exploit it took time. Under Falkenhayn, the procurement of ammunition and the guns to fire it, had been based on the output of propellants, since the manufacture of ammunition without sufficient propellant fillings, was as wasteful of resources as it was pointless but Hindenburg and Ludendorff wanted firepower to replace manpower and ignored the principle.[16]

To meet existing demand and to feed new weapons, Hindenburg and Ludendorff wanted a big increase in propellant output to 12,000 long tons (12,000 t) a month. In July 1916, the output target had been raised from 7,900–9,800 long tons (8,000–10,000 t) which was expected to cover existing demand and the extra 2,000 long tons (2,000 t) of output demanded by Hindenburg and Ludendorff could never match the doubling and trebling of artillery, machine-guns and trench mortars. The industrial mobilisation needed to fulfil the Hindenburg Programme increased demand for skilled workers, Zurückgestellte (recalled from the army) or exempted from conscription. The number of Zurückgestellte increased from 1.2 million men, of whom 740,000 were deemed kriegsverwendungsfähig (kv, fit for front line service), at the end of 1916 to 1.64 million men in October 1917 and more than two million by November, 1.16 million being kv. The demands of the Hindenburg Programme exacerbated the manpower crisis and constraints on the availability of raw materials meant that targets were not met.[17]

The German army returned 125,000 skilled workers to the war economy and exempted 800,000 workers from conscription, from September 1916 to July 1917.[18] Steel production in February 1917 was 252,000 long tons (256,000 t) short of expectations and explosives production was 1,100 long tons (1,100 t) below the target, which added to the pressure on Ludendorff to retreat to the Hindenburg Line.[19] Despite the shortfalls, by the summer of 1917, the Westheer artillery park had increased from 5,300 to 6,700 field guns and from 3,700 to 4,300 heavy guns, many being newer models of superior performance. Machine-gun output enabled each division to have 54 heavy and 108 light machine-guns and for the number of Maschinengewehr-Scharfschützen-Abteilungen (MGA, machine-gun sharpshooter detachments) to be increased. The increased output was insufficient to equip the new divisions and divisions which still had tow artillery brigades with two regiments lost a regiment and the brigade headquarters, leaving three regiments. Against the new scales of equipment, British divisions in early 1917 had 64 heavy and 192 light machine-guns and the French 88 heavy and 432 light machine-guns.[20]

Defensive battle

In a new manual of 1 December 1916, Grundsätze für die Führung in der Abwehrschlacht im Stellungskrieg (Principles of Command for Defensive Battle), the policy of unyielding defence of ground regardless of its tactical value, was replaced by the defence of positions suitable for artillery observation and communication with the rear, where an attacking force would "fight itself to a standstill and use up its resources while the defenders conserve[d] their strength". Defending infantry would fight in areas, with the front divisions in an outpost zone up to 3,000 yd (1.7 mi; 2.7 km) deep behind listening posts, with the main line of resistance placed on a reverse slope, in front of artillery observation posts, which were kept far enough back to retain observation over the outpost zone. Behind the main line of resistance was a Grosskampfzone (battle zone), a second defensive area 1,500–2,500 yd (0.85–1.42 mi; 1.4–2.3 km)}} deep, also placed as far as possible on ground hidden from enemy observation, while in view of German artillery observers.[21] A rückwärtige Kampfzone (rear battle zone) further back was to be occupied by the reserve battalion of each regiment.[22]

Field fortification

Allgemeines über Stellungsbau (Principles of Field Fortification) was published in January 1917 and by April an outpost zone (Vorpostenfeld) held by sentries, had been built along the Western Front. Sentries could retreat to larger positions (Gruppennester) held by Stoßtrupps (five men and an NCO per Trupp), who would join the sentries to recapture sentry-posts by immediate counter-attack. Defensive procedures in the battle zone were similar but with greater numbers. The front trench system was the sentry line for the battle zone garrison, which was allowed to move away from concentrations of enemy fire and then counter-attack to recover the battle and outpost zones; such withdrawals were envisaged as occurring on small parts of the battlefield which had been made untenable by Allied artillery fire, as the prelude to Gegenstoß in der Stellung (immediate counter-attack within the position). Such a decentralised battle by large numbers of small infantry detachments would present the attacker with unforeseen obstructions. Resistance from troops equipped with automatic weapons, supported by observed artillery fire, would increase the further the advance progressed. A school was opened in January 1917 to teach infantry commanders the new methods.[23]

Given the Allies' growing superiority in munitions and manpower, attackers might still penetrate to the second (artillery protection) line, leaving in their wake German garrisons isolated in Widerstandsnester, (resistance nests, Widas) still inflicting losses and disorganisation on the attackers. As the attackers tried to capture the Widas and dig in near the German second line, Sturmbattalions and Sturmregimenter of the counter-attack divisions would advance from the rückwärtige Kampfzone into the battle zone, in an immediate counter-attack, (Gegenstoß aus der Tiefe). If the immediate counter-attack failed, the counter-attack divisions would take their time to prepare a methodical attack if the lost ground was essential to the retention of the main position. Such methods required large numbers of reserve divisions ready to move to the battlefront. The reserve was obtained by creating 22 divisions by internal reorganisation of the army, bringing divisions from the eastern front and by shortening the western front, in Operation Alberich. By the spring of 1917, the German army in the west had a strategic reserve of 40 divisions.[24]

Somme analysis

Experience of the German 1st Army in the Somme Battles, (Erfahrungen der I Armee in der Sommeschlacht) was published on 30 January 1917. Ludendorff's new defensive methods had been controversial; during the Battle of the Somme in 1916 Colonel Fritz von Loßberg (Chief of Staff of the 1st Army) had been able to establish a line of relief divisions (Ablösungsdivisionen), with the reinforcements from Verdun, which began to arrive in greater numbers in September. In his analysis of the battle, Loßberg opposed the granting of discretion to front trench garrisons to retire, as he believed that manoeuvre did not allow the garrisons to evade Allied artillery fire, which could blanket the forward area and invited enemy infantry to occupy vacant areas. Loßberg considered that spontaneous withdrawals would disrupt the counter-attack reserves as they deployed and further deprive battalion and division commanders of the ability to conduct an organised defence, which the dispersal of infantry over a wider area had already made difficult. Loßberg and others had severe doubts as to the ability of relief divisions to arrive on the battlefield in time to conduct an immediate counter-attack (Gegenstoß) from behind the battle zone. The sceptics wanted the Somme practice of fighting in the front line to be retained and authority devolved no further than battalion, so as to maintain organizational coherence, in anticipation of a methodical counter-attack (Gegenangriff) after 24–48 hours, by the relief divisions. Ludendorff was sufficiently impressed by Loßberg's memorandum to add it to the new Manual of Infantry Training for War.[25]

6th Army

General Ludwig von Falkenhausen, commander of the 6th Army arranged his infantry in the Arras area according to Loßberg and Hoen's preference for a rigid defence of the front-line, supported by methodical counter-attacks (Gegenangriffe), by the "relief" divisions (Ablösungsdivisionen) on the second or third day. Five Ablösungsdivisionen were placed behind Douai, 15 mi (24 km) away from the front line.[26] The new Hindenburg line ended at Telegraph Hill between Neuville-Vitasse and Tilloy lez Mofflaines, from whence the original system of four lines 75–150 yd (69–137 m) apart, ran north to the Neuville St. Vaast–Bailleul road. About 3 mi (4.8 km) behind, were the Wancourt–Feuchy and to the north the Point du Jour lines, running from the Scarpe river north along the east slope of Vimy ridge. The new Wotan line, which extended the Hindenburg position, was built around 4 mi (6.4 km) further back and not entirely mapped by the Allies until the battle had begun.[27]

Just before the battle, Falkenhausen had written that parts of the front line might be lost but the five Ablösungsdivisionen could be brought forward, to relieve the front divisions on the evening of the second day. On 6 April, General von Nagel, the 6th Army Chief of Staff, accepted that some of the front divisions might need to be relieved on the first evening of battle but that any penetrations would be repulsed with local immediate counter-attacks (Gegenangriffe in der Stellung) by the front divisions. On 7 April, Nagel viewed the imminent British attack as a limited effort against Vimy Ridge, preparatory to a bigger attack later, perhaps combined with the French attack expected in mid-April.[28] Construction of positions to fulfil the new policy of area defence, had been drastically curtailed by shortages of labour and the long winter, which affected the setting of concrete. The 6th Army commanders had also been reluctant to encourage the British to change their plans, if they detected a thinning of the front line. The commanders were inhibited by the extent of British air reconnaissance, which observed new field works and promptly directed artillery fire on them. The 6th Army failed to redeploy its artillery, which remained in lines easy to see and bombard. Work on defences was also divided between maintaining the front line, strengthening the third line and the new Wotanstellung (Drocourt–Quéant switch line) further back.[29]

Corps

Corps were detached from their component divisions and given permanent areas to hold, named after the commander and then under a geographical title from 3 April 1917. The VIII Reserve Corps holding the area north of Givenchy became Gruppe Souchez, I Bavarian Reserve Corps became Gruppe Vimy and held the front from Givenchy to the Scarpe river with three divisions, Gruppe Arras (IX Reserve Corps) was responsible for the line from the Scarpe to Croisilles and Gruppe Quéant (XIV Reserve Corps) from Croisilles to Mœuvres. Divisions would move into the area and come under the authority of the group for the duration of their term, then be replaced by fresh divisions.[30]

Division

Using the new defensive system, the 18th Division in the German 1st Army, held an area of the Hindenburg Position with an outpost zone along a ridge near La Vacquerie and a main line of resistance 600 yd (550 m) behind. The battle zone was 2,000 yd (1,800 m) deep and backed onto the Hindenburg line. The three regiments held sectors with two battalions in the outpost and battle zones and one in reserve, several miles to the rear (this deployment was reversed later in the year). The two battalions were side by side, with three companies in the outpost zone and front trenches, one in the battle zone and four or five fortified areas within it (Widerstandsnester), built of concrete and sited for all-round-defence, held by one or two Gruppen (eleven men and an NCO) with a machine-gun and crew each; 3+1⁄2 companies remained in each front battalion area for mobile defence; during attacks the reserve battalion was to advance and occupy the Hindenburg line. The new dispositions doubled the area held by a unit, compared to July 1916 on the Somme.[31]

The British set-piece attack, early 1917

Division attack training

In December 1916, the training manual SS 135 replaced SS 109 of 8 May 1916 and marked a significant step in the evolution of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) into a homogeneous force, well adapted to its role on the Western Front.[32] The duties of army, corps and divisions in planning attacks were standardised. Armies were to devise the plan and the principles of the artillery component. Each corps was to allot tasks to divisions, which would then select objectives and devise infantry plans subject to corps approval. Artillery planning was controlled by corps with consultation of divisions by the corps General Officer Commanding, Royal Artillery (GOCRA) which became the title of the officer at each level of command who devised the bombardment plan, which was coordinated with neighbouring corps artillery commanders by the army GOCRA. Specific parts of the bombardment were nominated by divisions, using their local knowledge and the results of air reconnaissance. The corps artillery commander was to co-ordinate counter-battery fire and the howitzer bombardment for zero hour. Corps controlled the creeping barrage but divisions were given authority over extra batteries added to the barrage, which could be switched to other targets by the divisional commander and brigade commanders. SS 135 provided the basis for the BEF's operational technique for the rest of 1917.[33]

Platoon attack training

The training manual SS 143 of February 1917 marked the end of attacks made by lines of infantry with a few detached specialists.[34] The platoon was divided into a small headquarters and four sections, one with two trained grenade-throwers and assistants, the second with a Lewis gunner and nine assistants carrying 30 drums of ammunition, the third section comprised a sniper, scout and nine riflemen and the fourth section had nine men with four rifle-grenade launchers.[35] The rifle and hand-grenade sections were to advance in front of the Lewis-gun and rifle-grenade sections, in two waves or in artillery formation, which covered an area 100 yd (91 m) wide and 50 yd (46 m) deep, with the four sections in a diamond pattern, the rifle section ahead, rifle grenade and bombing sections to the sides and the Lewis gun section behind, until resistance was met. German defenders were to be suppressed by fire from the Lewis-gun and rifle-grenade sections, while the riflemen and hand-grenade sections moved forward, preferably by infiltrating round the flanks of the resistance, to overwhelm the defenders from the rear.[36]

The changes in equipment, organisation and formation were elaborated in SS 144 The Normal Formation For the Attack of February 1917, which recommended that the leading troops should push on to the final objective, when only one or two were involved but that for a greater number of objectives, when artillery covering fire was available for the depth of the intended advance, fresh platoons should leap-frog through the leading platoons to the next objective.[37] The new organisations and equipment gave the infantry platoon the capacity for fire and manoeuvre, even in the absence of adequate artillery support. To bring uniformity in adoption of the methods laid down in the revised manuals and others produced over the winter, Haig established a BEF Training Directorate in January 1917, to issue manuals and oversee training. SS 143 and its companion manuals like SS 144, provided British infantry with "off-the-peg" tactics, devised from the experience of the Somme and from French Army operations, to go with the new equipment made available by increasing British and Allied war production and better understanding of the organisation necessary to exploit it in battle.[38]

British offensive preparations

Planning for operations in 1917 began in late 1916. Third Army staff made their proposals for what became the Battle of Arras on 28 December, beginning a process of consultation and negotiation with GHQ. Sir Douglas Haig, Commander-in-Chief of the BEF, studied this draft and made amendments, resulting in a more cautious plan for the infantry advance. General Edmund Allenby, in command of the Third Army proposed to use Corps mounted troops and infantry to press ahead beyond the main body, which was accepted by Haig, since the new dispersed German defensive organisation gave more scope to cavalry.[39] Third Army's claims on manpower, aircraft, tanks and gas were agreed and its corps were instructed to make their plans according to SS 135 Instructions for the Training of Divisions for Offensive Action of December 1916. Behind the lines (defined as the area not subject to German artillery fire) improvements in infrastructure and supply organisation made in 1916, had led to the creation of a Directorate-General of Transportation (10 October 1916) and a Directorate of Roads (1 December) allowing army headquarters to concentrate on operations.[40]

Allenby and his artillery commander planned a 48-hour bombardment based on the experience of the Somme, apart from its relatively short duration, after which the infantry were to advance deep into the German defences, then move sideways to envelop areas where the Germans had held their ground. The 2,817 guns, 2,340 Livens projectors and 60 tanks massed in the Third and First armies, were deployed in relation to the length of front, the quantity of wire to be cut and availability of the new fuze 106.[41] Guns and howitzers were allotted according to their calibre and the nature of the targets to be engaged. Several barrages were planned for the attack, which deepened the area under bombardment. Great stress was laid on counter-battery fire under a Counter-Battery Staff Officer with the use of sound ranging to find the positions of German artillery.[42]

A short bombardment was over-ruled by Haig and Allenby's artillery commander was promoted out of the way and replaced by Major-General R. St. C. Lecky, who wanted a longer bombardment, as did Major-General Herbert Uniacke, loaned by the Fifth Army during Lecky's absence through illness.[40] In conferences with his corps commanders, Allenby used a consultative style at first, encouraging the corps commanders to solicit suggestions from subordinates (26 February) but later changed bombardment and counter-battery plans without discussion (2 March), although his instructions to the Cavalry Corps gave the commander freedom of action in liaison with the other corps.[39] During the course of the battle Allenby (Third Army Artillery Instructions No.13, 19 April 1917) recommended that artillery batteries should be set aside to deal with German counter-attacks, which had become more effective as the Germans recovered from the initial shock of the attack, to be linked to the front by wireless and registered on probable German forming-up places. On 19 April, Notes on Points of Instructional Value (No. G.14 66.), was circulated as far as battalions, showing the increased effort being made to address the chronic difficulty in communication once operations commenced.[43]

Matters were similarly settled in the First Army further north, which had responsibility for the capture of Vimy Ridge, to form a flank guard to the Third Army. The commander Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Horne, maintained a consultative style in contrast to Allenby's move towards prescriptive control. On 18 March, the XI Corps commander, Lieutenant-General Richard Haking, drew attention to two of his divisions, which were holding a four-division front and Horne explained the vital nature of the attack on the ridge, by I Corps and the Canadian Corps further south. Conferences with the corps commanders on 29 March and 15 April, discussed the corps commanders' opinions on the possibility of a German withdrawal, road allocations and catering arrangements for the troops in the line, the vital importance of troops communicating with contact aeroplanes and artillery and the dates by which the corps commanders felt able to attack.[44]

Corps

XVII Corps issued a 56-page plan of "Instructions on which Divisional Commanders are to work out their own plans in detail...", which incorporated experience gained on the Somme and stressed the importance of co-ordinated machine-gun fire, counter-battery artillery fire, creeping barrages, the leapfrogging of infantry units, pauses on objectives and plans to meet German counter-attacks. Mortar and gas units were delegated to divisional control. Tank operations remained a corps responsibility, as they were to conform to an army plan against selected objectives. A Corps Signals Officer was appointed, to co-ordinate artillery communications on lines later elaborated in SS 148 Forward Inter-Communication in Battle of March 1917, going into the details of telephone line planning, to link units with each other, neighbours and their artillery, along with telegraph, visual signalling, pigeons, power buzzers, wireless, codes and liaison with the Royal Flying Corps (RFC).[42]

Much of the corps planning covered artillery, detailing the guns to move forward behind the infantry and their new positions. Artillery liaison officers were appointed to infantry units and field guns and howitzers were reserved to engage German counter-attacks. It was laid down that artillery supporting a neighbouring division was to come under the command of that division.[45] For the first time all artillery was integrated into one plan. Planning for the Battle of Arras showed that command relationships, especially within the artillery (which had evolved a parallel system of command, so that General Officers Commanding, Royal Artillery at corps and division were much more closely integrated) and standardisation, had become more evident between armies, corps and divisions. Analysis and codification of the lessons of the Somme and the process of supplying the armies, made the BEF much less dependent on improvisation. Discussion and dissent between army, corps and division was tolerated, although it was not uniformly evident. Staffs were more experienced and were able to use a formula for set-piece attacks, although the means for a higher tempo of operations had not been achieved, because of the artillery's reliance on observed fire, which took time to complete. The loss of communication with troops once they advanced, still left their commanders ignorant of events when their decisions were most needed.[46]

Division

Intelligence Officers were added to divisions, to liaise with headquarters as their units moved forward and to report on progress, to increase the means by which commanders could respond to events.[47] Training for the attack had begun in the 56th Division in late March, mainly practising for open warfare ("greeted with hilarity") with platoons organised according to SS 143.[48] Instructions from the corps headquarters, restricted light signals to the artillery to green for "open fire" and white for "increase the range" and laid down the strength of battalions, the number of officers and men to be left out of battle and formed into a Divisional Depot Battalion. The two attacking brigades returned to the line on 1 April, giving them plenty of time to study the ground before the attack on 9 April.[49]

On 15 April, during the Battle of Arras, VI Corps forwarded to Allenby a report that a conference of the commanders of the 17th Division, 29th Division and 50th Division and the corps Brigadier-General General Staff (BGGS), had resolved that the recent piecemeal attacks should stop and that larger coordinated actions should be conducted after a pause to reorganise, which Allenby accepted.[50] On 17 April, the 56th Division commander objected to an operation planned for 20 April, due to the exhaustion of his troops. The division was withdrawn instead, when the VI and VII corps commanders and General Horne, the First Army commander also pressed for a delay. VI Corps delegated the barrage arrangements for the attack on 23 April, to the divisions involved, which included variations in the speed of the barrage, to be determined by the state of the ground. Reference was made in Third Army Artillery Instructions No.12 (18 April) to SS 134 Instructions on the Use of Lethal and Lachrymatory Shell and an Army memo, regarding low flying German aeroplanes, called attention to SS 142 Notes on Firing at Aircraft with Machine Guns and Other Small Arms. Third Army Headquarters also gave its corps permission to delegate command of tanks to divisions for the Second Battle of the Scarpe (23–24 April), discretion over local matters being increasingly left to divisional commanders, with corps retaining control over matters affecting the conduct of the battle in general.[51]

British methodical attacks

After 12 April, Haig decided that the advantage gained by the Third and First armies since 9 April, had run its course and that further attacks must resume a methodical character. British intelligence estimated that nine German divisions had been relieved with nine fresh ones. On 20 April, after the commencement of the French attacks of the Nivelle offensive, Haig believed that the German reserve had fallen from 40–26 fresh divisions but that thirteen tired divisions were recovering and that there were ten new divisions available for the Western Front. With the reliefs due on the French front, only about eleven fresh divisions would remain to oppose further British operations, which were conducted until early May.[52]

German defensive changes

The first days of the British Arras offensive, saw another German defensive debacle similar to that at Verdun on 15 December 1916, despite an analysis of that failure being issued swiftly, which concluded that deep dug-outs in the front line and an absence of reserves for immediate counter-attacks, were the cause of the defeat.[53] At Arras similarly obsolete defences over-manned by infantry, were devastated by artillery and swiftly overrun, leaving the local reserves with little choice but to try to contain further British advances and wait for the relief divisions, which were too far away to counter-attack. Seven German divisions were defeated, losing 15,948 men and 230 guns on 9 April.[54] Given the two failures and the imminence of the French offensive on the Aisne, the term Ablösungsdivision was dropped in favour of Eingreif division, a term with connotations of interlocking and dovetailing, to avoid the impression that they were replacement divisions standing by, rather than reinforcements fundamental to the defence of the battle zones, by operating support of the local garrisons of the Stellungsdivisionen. A more practical change, was the despatch of Loßberg from his post as Chief of Staff of the German 1st Army, (due to move south to join the armies on the Aisne) to the 6th Army, replacing Nagel on 11 April.[55] Falkenhausen was sacked on 23 April and replaced by General Otto von Below.[56]

Loßberg made a swift reconnaissance of the 6th Army area, as the British were attacking Bullecourt at the north end of the Siegfriedstellung (Hindenburg line). He confirmed the decision made to withdraw from the Wancourt salient and the foot of Vimy Ridge, accepting that a rigid forward defence was impossible given British observation from the ridge. North of the Scarpe, the front garrison was given permission to withdraw during British attacks, from the battle zone to its rear edge, where it would counter-attack with the reserves held back there and mingle with retreating British infantry, to evade British observed artillery fire; after dark the German infantry would be redeployed in depth under cover. South of the Scarpe, the loss of Monchy-le-Preux also gave the British observation over German positions. Loßberg mapped a new line beyond the range of British field artillery, to be the back of a new battle zone (the Boiry–Fresnes Riegel). At the front of the battle zone he chose the old third line from Méricourt to Oppy, then a new line along reverse slopes from Oppy to the Hindenburg Position at Moulin-sans-Souci, creating a battle zone 2,500 yd (1.4 mi; 2.3 km) deep. A rearward battle zone 3,000 yd (1.7 mi; 2.7 km) backed on to the Wotan line, which was nearing completion.[57]

Despite Loßberg's doubts about elastic defence, the circumstances he found on the 6th Army front made resort to it unavoidable. With artillery reinforcements arriving, the first line of defence was to be a heavy barrage (Vernichtungsfeuer) on the British front line, at the commencement of a British attack, followed by direct and indirect machine-gun fire on the British infantry, as they tried to advance through the German battle zone, followed by infantry counter-attacks by local reserves and Eingreif divisions (if needed) to regain the front position. As the British might try to capture ground north of the Scarpe, using their observation from Vimy ridge over the German positions, Loßberg requested that a new Wotan II Stellung be built from Douai south to the Siegfried II Stellung (Hindenburg Support line). In the battle zone between the front line and the Boiry–Fresnes Riegel, Loßberg ordered that digging-in was to be avoided, in favour of the maximum use of invisibility (die Leere des Gefechtsfeldes). Machine-guns were not to be placed in special defended localities as in the Siegfriedstellung but to be moved among shell-holes and improvised emplacements, as the situation demanded. Specialist (Scharfschützen) machine-gun units with 15–20 guns each per division, were moved back to the artillery protective line, to act as rallying points, (Anklammerungspunkte) for the front garrison and as the fire power to cover the advance of Eingreif units. Artillery was concealed in the same manner, lines of guns were abolished and guns were placed in folds of ground and frequently moved, to mislead British air observation, which was made easier by a period of poor weather. The new deployment was ready by 13 April; the remnants of the original front-line divisions had been withdrawn and replaced by nine fresh divisions, with six more brought into the area, as new Eingreif divisions.[58]

The British set-piece attack, mid-1917

Army

Sir Douglas Haig chose General Hubert Gough, commander of the Fifth Army to lead the offensive from the Ypres salient. Gough held the first conference in late 24 May, before he moved his headquarters to the Salient. II Corps, XIX Corps, XVIII Corps and XIV Corps were to be under the command of the Fifth Army and IX Corps, X Corps and II Anzac Corps in the Second Army. As early decisions were subject to change, detail was avoided, planners were to draw on "Preparatory measures to be taken by Armies and Corps before undertaking operations on a large scale" of February 1916 and SS 135. It was decided to have four divisions per corps, two for the attack and two in reserve, with staff from the reserve division headquarters taking over before the original divisions were relieved. On 31 May Gough, dealt with a letter from the XVIII Corps commander Lieutenant-General Ivor Maxse objecting to dawn attacks, since a later time gave troops more rest before the attack. Maxse also wanted to go beyond the black line (second objective) to the Steenbeek stream, to avoid stopping on a forward slope. Gough replied that he had to consider the wishes of all the corps commanders but agreed with the wisdom of trying to gain as much ground as possible, which Gough felt had not been achieved by the Third Army at Arras.[59]

In 1915, the biggest operation of the BEF had been by one army, with three corps and nine divisions. In 1916, two armies, nine corps and 47 divisions, fought the Battle of the Somme, without the benefit of the decades of staff officer experience that continental conscript armies could take for granted.[60] Rather than the elaborate plans, made to compensate for the limited experience of many staff officers and commanders common in 1916, (the XIII Corps Plan of Operations and Operational Order 14 for 1 July 1916 covered 31 pages, excluding maps and appendices), the XVIII Corps Instruction No.1, was only 23 pages long and concerned principles and the commander's intent, as laid down in Field Service Regulations 1909.[61] Details had become routine, as more staff officers gained experience, allowing more delegation.[62]

Great emphasis was placed on getting information back to headquarters and making troops independent within the plan, to allow a higher tempo ("The rate or rhythm of activity relative to the enemy".) of operations, by freeing attacking troops from the need to refer back for orders.[63] Corps commanders planned the attack in the framework given by the army commander and planning in the Second Army followed the same system. In mid-June, the corps in the Second Army corps were asked to submit their attack plans and requirements to carry them out. When the II Corps boundary was moved south in early July, the Second Army attack became mainly a decoy, except for the 41st Division (X Corps), for which special liaison arrangements were made with II Corps and the covering artillery.[64]

At the end of June, Major-General John Davidson, Director of Operations at GHQ, wrote a memorandum to Haig, in which he wrote that there was "ambiguity as to what was meant by a step-by-step attack with limited objectives" and advocated advances of no more than 1,500–3,000 yd (0.85–1.70 mi; 1.4–2.7 km), to increase the concentration of British artillery and operational pauses, to allow for roads to be repaired and artillery to be moved forward.[65] A rolling offensive would need fewer periods of intense artillery fire, which would allow guns to be moved forward ready for the next stage. Gough stressed the need to plan for opportunities to take ground left temporarily undefended and that this was more likely in the first attack,

It is important to recognise that the results to be looked for from a well-organised attack which has taken weeks and months to prepare are great, much ground can be gained and prisoners and guns captured during the first day or two.[66] I think we should certainly aim at the definite capture of the Green line, and that, should the situation admit of our infantry advancing without much opposition to the Red line, it would be of the greatest advantage to us to do so.[67]

Haig arranged a meeting with Davidson, Gough and Plumer on 28 June, where Plumer supported the Gough plan.[68][69] Maxse the XVIII Corps commander, left numerous sarcastic comments in the margins of his copy of the Davidson memo, to the effect that he was being too pessimistic. Davidson advocated views which were little different from those of Gough, except for Gough wanting to make additional arrangements, to allow undefended ground to be captured by local initiative.[70][b].[72] An advance of 5,000 yd (2.8 mi; 4.6 km) to the red line, was not fundamental to the plan and discretion to attempt it was left with the divisional commanders, based on the extent of local German resistance, according to the requirements of SS 135. Had the German defence collapsed and the red line been reached, the German Flandern I, II and III Stellungen would have been intact, except for Flandern I Stellung for 1 mi (1.6 km) south of Broodseinde.[73] On 10 August, II Corps was required to reach the black line of 31 July, an advance of 400–900 yd (370–820 m) and at the Battle of Langemarck on 16 August, the Fifth Army was to advance 1,500 yd (1,400 m).[74]}}

Corps

At the conference on 6 June, Gough took the view that if the Germans were thoroughly demoralised, it might be possible to advance to parts of the red line on the first day. Maxse and Rudolph Cavan (XIV Corps), felt that the range of their artillery would determine the extent of their advance and that it would need to be moved forward for the next attack. Gough drew a distinction between advancing against disorganised enemy forces, which required bold action and attacks on organised forces, which needed careful preparation, particularly of the artillery which would take three to seven days. Maxse's preference for a later beginning for the attack was agreed, except by Lieutenant-General Herbert Watts, the XIX Corps commander. A memorandum was issued summarising the conference, in which Gough stressed his belief in the need for front-line commanders to use initiative and advance into vacant or lightly-occupied ground beyond the objectives laid down, without waiting for orders.[75] Relieving tired troops, gave time to the enemy, so a return to deliberate methods would be necessary afterwards. Judging the time for this was reserved for the army commander, who would rely on the reports of subordinates.[75]

Communication by the Fifth Army corps to their divisions, reflected the experience of Vimy and Messines, the value of aerial photography for counter-battery operations, raiding and the construction of scale models of the ground to be covered, the divisional infantry plans, machine-gun positions, mortar plans and positions, trench tramways, places chosen for supply dumps and headquarters, signals and medical arrangements and camouflage plans. The Corps was responsible for heavy weapons, infrastructure and communication. In XIV Corps, divisions were to liaise with 9 Squadron RFC for training and to conduct frequent rehearsals of infantry operations, to give commanders experience in dealing with unexpected occurrences, which were more prevalent in semi-open warfare.[76]

XIV Corps held a conference of divisional commanders on 14 June and Cavan emphasised the importance of using the new manuals (SS 135, SS 143 and Fifth Army document S.G. 671 1) in planning the offensive. Discussion followed on the means by which the Guards Division and 38th Division were to meet the army commander's intent. The decision to patrol towards the red line, was left to the discretion of divisional commanders.[77] An attack of this nature was not a breakthrough operation; the German defensive position Flandern I Stellung lay 10,000–12,000 yd (5.7–6.8 mi; 9.1–11.0 km) behind the front line and would not be attacked on the first day but it was more ambitious than Plumer's plan, which had involved an advance of 1,000–1,750 yd (910–1,600 m).[78] Notes were later sent to the divisions, from the next army conference held on 19 June.[79]

At a conference held by Gough on 26 June, the record (Fifth Army S.G.657 44), was written up as the operation order for the attack of 31 July, in which the final objective for the first day, was moved forward from the black to the green line and infiltration envisaged from it towards the red line. Responsibility delegated to the divisions for the attack, would revert to corps and Fifth Army headquarters, when the green line was reached. In Gough's Instruction of 27 June, he alluded to Davidson's concern about a ragged front line, by reminding the Corps commanders that a "clearly defined" line was needed for the next advance and that control of artillery would be devolved to the corps.[77] Gough issued another memorandum on 30 June, summarising the plan and referring to the possibility that the attack would move to open warfare after 36 hours, noting that this might take several set-piece battles to achieve.[80]

XVIII Corps issued Instruction No. 1 on 30 June, describing the intention to conduct a rolling offensive, where each corps would have four divisions, two for the attack and two in reserve, ready to move through the attacking divisions for the next attack. Separate units were detailed for patrolling, once the green line was reached and some cavalry were attached. Divisions were to build strongpoints and organise liaison with neighbouring divisions, with these groups given special training over model trenches. Ten days before zero, divisions were to send liaison officers to Corps Headquarters. Machine-gun units were to be under corps control, until the black line was reached then devolve to divisions, ready to sweep the Steenbeek valley and cover the advance to the green line by the 51st and 39th divisions. Tanks were attached to the divisions, under arrangements decided by the divisions and some wireless tanks were made available. Gas units remained under corps control, a model of the ground was built for all ranks to inspect and it was arranged that two maps per platoon would be issued. Plans for air-ground communication went into considerable detail. Aircraft recognition markings were given and the flares to be lit by the infantry when called for by contact aeroplanes was laid down, as were recognition marks for battalion and brigade headquarters; dropping stations were created to receive information from aircraft. Ground communication arrangements were made according to the manual SS 148. Appendices covered Engineer work on roads, rail, tramways and water supply; intelligence arrangements covered the use balloons, contact aeroplanes, Forward Observation Officers, prisoners, returning wounded, neighbouring formations and wireless eavesdropping. Corps Observers were attached to brigades, to patrol forward once the black line was reached, to observe the area up to the green line, judge the morale of the Germans opposite and see if they were preparing to counter-attack or retire, passing the information to a divisional Advanced Report Centre.[81]

Division

Training for the northern attack (31 July) began in early June, with emphasis on musketry and attacks on fortified positions. The Guards Division Signals Company trained 28 men from each brigade as relay runners, additional to the other means of tactical communication. Major-General Fielding held a conference on 10 June, to discuss the division's place in the XIV Corps scheme, for the attack east and north-east of Boesinghe. Four "bounds" were to be made to the blue, black, green and dotted green lines, bypassing isolated German posts, which were to be dealt with by reserves. Depending on the state of the German defence, ground was to be taken up to the red line by patrols. Captured German trench lines were to be consolidated and advanced posts established beyond them. Parties were to be detailed for liaison with neighbouring units and divisions. Six brigades of field artillery were available for the creeping barrage and the division's three machine-gun companies were reinforced by a company from the 29th Division for the machine-gun barrage. Times when contact patrol aircraft were to fly overhead observing progress were given. The only light signals allowed were the flares for contact aircraft and the rifle grenade SOS signal.[82]

On 12 June, the 2nd Guards Brigade began the march to the front line and on 15 June, the relief of 38th Division commenced and preparations were begun to cross the Yser canal, which was 23 yd (21 m) wide, empty and with deep mud in the bed. A divisional conference on 18 June, discussed the plans of the 2nd and 3rd Guards Brigades and their liaison arrangements, with 38th Division to the right and the French 1st Division on the left. The divisional reserve of the 1st Guards Brigade, was to exploit success by forcing a crossing of the Steenbeek and consolidating a bridgehead on the far bank. If the Germans collapsed, it was to advance to a line east of Langemarck and Wijdendreft.[83]

The 8th Division moved to Flanders a few days before the Battle of Messines Ridge (7–17 June) and joined XIV Corps in Second Army reserve. On 11 June, the division came under II Corps and began to relieve parts of 33rd Division and the 55th Division on the Menin Road at Hooge. Major-General William Heneker was able to persuade Gough to cancel a preliminary operation and include it in the main attack. On 12 July, the Germans conducted their first mustard gas attack on the divisional rear areas and artillery lines.[84] Two brigades were to advance to the blue line with two battalions each, with the other two to pass through to the black line; four tanks were attached to each brigade. The 25th Brigade would then attack the green line, assisted by twelve tanks. One battalion with tanks and cavalry would then be ready to advance to the red line, depending on the state of German resistance and the 25th Division would be in reserve, ready to attack beyond the red line.[85]

After a night raid on 11 July, the division was relieved by the 25th Division and began training intensively for trench-to-trench attacks, on ground marked to represent German positions on the objective. A large model was built and a large-scale map produced for officers and men to study and reconnaissance was conducted by officers and staffs to see the ground up to the objective. The divisional artillery was reinforced with the 25th Divisional artillery, three army field brigades, a counter-battery double-group, (one with 6-inch, 8-inch and 12-inch howitzers, the other with 60-pounder and 6-inch guns) a double bombardment group (one group with 6-inch and 8-inch howitzers, the other with 6-inch, 9.2-inch and 15-inch howitzers). Six batteries of 2-inch, three of 6-inch and four of 9.45-inch mortars were added. On 23 July, the division returned to the front line and commenced raiding, to take prisoners and to watch for a local withdrawal, while tunnelling companies prepared large underground chambers, to shelter the attacking infantry before the offensive began.[86]

German defensive preparations, June–July 1917

Heeresgruppe Kronprinz Rupprecht

Northern France and Flanders was held by Army Group Crown Prince Rupprecht, which by the end of July had 65 divisions.[87] The defence of the Ypres Salient was the responsibility of the German 4th Army, under the command of General Friedrich Bertram Sixt von Armin. The divisions of the 4th Army were organised in groups (Gruppen) based on the existing corps organisation. Gruppe Lille ran from the southern army boundary to Warneton. Gruppe Wytschaete continued north to Bellewaarde Lake, Gruppe Ypres held the line to the Ypres–Staden railway, Gruppe Dixmude held the ground from north of the railway to Noordschoote and Gruppe Nord held the coast with Marinekorps Flandern.[88]

The 4th Army defended 25 mi (40 km) of front with Gruppe Dixmude based on the German XIV Corps headquarters, Gruppe Ypres (III Bavarian Corps) and Gruppe Wytschaete (IX Reserve Corps); Gruppe Staden (Guards Reserve Corps) was added later.[89] Gruppe Dixmude held 12 mi (19 km), with four front divisions and two Eingreif divisions; Gruppe Ypres held 6 mi (9.7 km) from Pilckem to Menin Road, with three front divisions and two Eingreif divisions and Gruppe Wytschaete held a similar length of front south of Menin Road with three front divisions and three Eingreif divisions. The Eingreif divisions were placed behind the Menin and Passchendaele Ridges; 5 mi (8.0 km) further back were four more Eingreif divisions and 7 mi (11 km) beyond them another two in "Group of Northern Armies" reserve.[89]

Behind ground-holding divisions (Stellungsdivisionen) was a line of Eingreif divisions. The term Ablösungsdivision had been dropped before the French offensive in mid-April, to avoid confusion over their purpose, the word Eingreif ("interlock", "dovetail" or "intervene") being substituted.[90] The 207th Division, 12th Division and 119th Division supported Gruppe Wytschaete, the 221st Division and 50th Reserve Division were in Gruppe Ypres and 2nd Guard Reserve Division supported Gruppe Dixmude. The 79th Reserve Division and 3rd Reserve Division were based at Roulers, in Army Group reserve. Gruppe Ghent, with the 23rd Division and 9th Reserve Division was concentrated around Ghent and Bruges, with the 5th Bavarian Division based at Antwerp, in case of a British landing in the Netherlands.[91]

The Germans were apprehensive of a British attempt to exploit the victory at the Battle of Messines, with an advance to the Tower Hamlets spur, beyond the north end of Messines Ridge. On 9 June, Rupprecht proposed withdrawing to the Flandern line in the area east of Messines. Construction of defences began but were terminated after Loßberg was appointed as the new Chief of Staff of the 4th Army.[92] Loßberg rejected the proposed withdrawal to the Flandern line and ordered that the front line east of the Oosttaverne line be held rigidly. The Flandernstellung (Flanders Position), along Passchendaele Ridge in front of the Flandern line, would become the Flandern I Stellung and a new Flandern II Stellung would run west of Menin and north to Passchendaele. Construction of the Flandern III Stellung east of Menin northwards to Moorslede was also begun. From mid-1917, the area east of Ypres was defended by six German defensive positions: the front line, the Albrechtstellung (second position), Wilhelmstellung (third position), Flandern I Stellung (fourth position), Flandern II Stellung (fifth position) and Flandern III Stellung (under construction). In between the German defence positions lay the Belgian villages of Zonnebeke and Passchendaele.[93]

Debate among the German commanders continued and on 25 June, Ludendorff suggested to Rupprecht that Gruppe Ypres be withdrawn to the Wilhelm Stellung, leaving only outposts in the Albrecht Stellung. On 30 June, Kuhl, suggested a withdrawal to the Flandern I Stellung along Passchendaele Ridge, meeting the old front line in the north near Langemarck and at Armentières to the south. Such a withdrawal would avoid a hasty retreat from Pilckem Ridge and also force the British into a time-consuming redeployment. Loßberg disagreed, believing that the British would launch a broad front offensive, that the ground east of the Oosttaverne line was easy to defend, that the Menin Road Ridge could be held and that Pilckem Ridge deprived the British of ground observation over the Steenbeek valley, while German observation of the area from Passchendaele Ridge allowed the infantry to be supported by observed artillery fire.[94]

4th Army

The 4th Army operation order for the defensive battle was issued on 27 June.[95] The system of defence in depth began with a front system (first line) of three breastworks Ia, Ib and Ic, about 200 yd (180 m) apart, garrisoned by the four companies of each front battalion with listening-posts in no-man's-land. About 2,000 yd (1,800 m) behind these works, was the Albrechtstellung (second or artillery protective line), the rear boundary of the forward battle zone (Kampffeld). Companies of the support battalions were split, 25 percent of which were Sicherheitsbesatzung to hold strong-points and 75 percent were Stoßtruppen to counter-attack towards them, from the back of the Kampffeld, half based in the pillboxes of the Albrechtstellung, to provide a framework for the re-establishment of defence in depth, once the enemy attack had been repulsed.[96] Dispersed in front of the line were divisional Sharpshooter (Scharfschützen) machine-gun nests, called the Stützpunktlinie. The Albrechtstellung also marked the front of the main battle zone (Grosskampffeld) which was about 2,000 yd (1,800 m) deep, containing most of the field artillery of the front divisions, behind which was the Wilhelmstellung (third line). In pillboxes of the Wilhelmstellung were reserve battalions of the front-line regiments, held back as divisional reserves.[97]

From the Wilhelm Stellung to the Flandern I Stellung was a rearward battle zone (rückwärtiges Kampffeld) containing support and reserve assembly areas for the Eingreif divisions. The failures at Verdun in December 1916 and at Arras in April 1917 had given more importance to these areas, since the Kampffeld had been overrun during both offensives and the garrisons lost. It was anticipated that the main defensive engagement would take place in the Grosskampffeld by the reserve regiments and Eingreif divisions, against attackers who had been slowed and depleted by the forward garrisons before these were destroyed.

... they will have done their duty so long as they compel the enemy to use up his supports, delay his entry into the position, and disorganise his waves of attack.

The leading regiment of the Eingreif division, was to advance into the zone of the front division, with its other two regiments moving forward in close support.[c] Eingreif divisions were accommodated 10,000–12,000 yd (5.7–6.8 mi; 9.1–11.0 km) behind the front line and began their advance to assembly areas in the rückwärtiges Kampffeld, ready to intervene in the Grosskampffeld, for den sofortigen Gegenstoß (the instant-immediate counter-thrust).[99][100] Loßberg rejected elastic defence tactics in Flanders, because there was little prospect of operational pauses between British attacks towards Flandern I Stellung. The British had such a mass of artillery and the infrastructure to supply it with huge amounts of ammunition, much of which had been built after the attack at Messines in early June. Loßberg ordered that the front line be fought for at all costs and immediate counter-attacks delivered to recapture lost sectors. Loßberg reiterated his belief that a trench garrison which retired in a zone of fire, quickly became disorganised and could not counter-attack, losing the sector and creating difficulties for troops on the flanks.[101]

Counter-attack was to be the main defensive tactic, since local withdrawals would only disorganise the troops moving forward to their assistance. Front line troops were not expected to cling to shelters, which were man traps but leave them as soon as the battle began, moving forward and to the flanks, to avoid enemy fire and to counter-attack. German infantry equipment had recently been improved by the arrival of 36 MG08/15 machine-guns (equivalent to the British Lewis gun) per regiment. The Trupp of eight men was augmented by a MG08/15 crew of four men, to become a Gruppe, with the Trupp becoming a Stoßtrupp. The extra firepower gave the German unit better means for fire and manoeuvre. Sixty percent of the front line garrison were Stoßtruppen and 40 per cent were Stoßgruppen, based in the forward battle zone. Eighty percent of the Stoßkompanien occupied the Albrecht Stellung and Stoß-batallione in divisional reserve (all being Stoß formations) and then the Eingreif division (all Stoß formations), was based in the Fredericus Rex and Triarii positions. The essence of all of these defensive preparations was riposte, in accordance with the view of Carl von Clausewitz, that defence foreshadows attack.[102]

The British set-piece attack, late 1917

Army

Staff at GHQ of the BEF, quickly studied the results of the attack of 31 July and on 7 August sent questions to the army headquarters, on how to attack in the new conditions produced by German defence-in-depth using strong points, pillboxes and rapid counter-attacks by local reserves and Eingreif divisions.[103][d] Plumer replied on 12 August, placing more emphasis on mopping up captured ground, making local reserves available to deal with hasty local counter-attacks and having larger numbers of reserves available to crush organised counter-attacks.[104] After a conference with the Corps commanders on 27 August, Plumer issued "Notes on Training and Preparation for Offensive Operations" on 31 August, which expanded on his reply to GHQ, describing the need for attacks with more depth and more scope for local initiative, enabled by unit commanders down to the infantry company keeping a reserve ready to meet counter-attacks. Communication was stressed but the standardisation achieved since 1916 allowed this to be reduced to a reference to SS 148.[105]

Plumer issued a "Preliminary Operations Order" on 1 September, defining an area of operations from Broodseinde southwards. Four corps with fourteen divisions, were to be involved in the attack.[e] Five of the thirteen Fifth Army divisions, extended the attack northwards to the Ypres–Staden railway; the process of arranging the attack involved the divisions soon afterwards.[106] New infantry formations were introduced by both armies, to counter the German irregular pillbox defence and the impossibility of maintaining line formations on ground full of flooded shell-craters. Waves of infantry were replaced by a thin line of skirmishers leading small columns. Maxse the XVIII Corps commander, called this one of the "distinguishing features" of the attack, along with the revival of the use of the rifle as the primary infantry weapon, the addition of Stokes mortars to creeping barrages and "draw net" barrages, where field guns began a barrage 1,500 yd (1,400 m) behind the German front line then crept towards it, which were fired several times before the attack began. The pattern of organisation established before the Battle of Menin Road Ridge, became the standard method of the Second Army.[107]

The plan relied on the use of more medium and heavy artillery, which was brought into the area of the Gheluvelt Plateau from VIII Corps on the right of the Second Army and by removing more guns from the Third and 4th armies further south.[108] The heavy artillery reinforcements were to be used destroy German strong points, pillboxes and machine-gun nests, which were more numerous beyond the German outpost zones already captured and to engage in more counter-battery fire.[109] 575 heavy and medium and 720 field guns and howitzers were allocated to Plumer for the battle, an equivalent of one artillery piece for every 5 yd (4.6 m) of the attack front, which was more than double the proportion for the Battle of Pilckem Ridge.[110] The ammunition requirements for a seven-day bombardment before to the assault, was estimated at 3.5 million rounds, which created a density of fire four times greater than for the attack of 31 July.[110] Heavy and medium howitzers were to make two layers of the creeping barrage, each 200 yd (180 m) deep, ahead of two field artillery belts equally deep, plus a machine-gun barrage in the middle. Beyond the "creeper", four heavy artillery counter-battery double groups, with 222 guns and howitzers, covered a 7,000 yd (4.0 mi; 6.4 km) front, ready to engage German guns which opened fire, with gas and high-explosive shell.[111]

Corps

The three-week operational pause in September, originated from Lieutenant-General Thomas Morland and Lieutenant-General William Birdwood the X Corps and I Anzac Corps commanders, at the conference of 27 August. The attacking corps made their plans within the framework of the Second Army plan, using "General Principles on Which the Artillery Plan Will be Drawn" of 29 August, which described the multi-layer creeping barrage and the use of fuze 106, to avoid adding more craters to the ground. Decisions over practice barrages and machine-gun barrages were left to the corps commanders. The Second Army and both corps did visibility tests, to decide when zero hour should be set and discussed the use of wireless and gun-carrying tanks with Plumer on 15 September. X Corps issued its first "Instruction" on 1 September, giving times and boundaries to its divisions, with details to follow.[112]

More details came from X Corps in a new "Instruction" on 7 September, giving the green line as the final objective for the attack and the black line for the next attack, which was expected to follow about six days later, reduced the depth of the barrage from 2,000–1,000 yd (1,830–910 m) and added a machine-gun barrage, to be fired by the attacking divisions and coordinated by the Corps Machine-Gun Officer and the Second Army artillery commander. Artillery details covered eight pages and signalling another seven. A Corps Intelligence balloon was arranged to receive light signals and messenger pigeons were issued to corps observers, reporting to a Corps Advanced Intelligence Report Centre, so that information could be collected and circulated swiftly. Delegation forward was demonstrated by the next "Instructions" on 10 September, which gave a framework for the creeping barrage fired by the divisional artillery, the details being left to the divisions, as was harassing fire on German positions. Double bombardment groups, which had been used by X Corps at Messines, were affiliated with divisional headquarters.[113] The X Corps report on the attack of 20 September, stated that success was due to the artillery and machine-gun barrages, the ease of moving troops over rebuilt roads and tracks behind the front and the much better co-operation of infantry, artillery and Royal Flying Corps.[114]

Division

On 7 September, the 1st Australian Division commander announced the attack to his staff and next day the ground was studied. "Divisional Order 31" was issued on 9 September, giving the intent of the operation and listed neighbouring formations, the placement of brigades and the deployment of the two attacking brigades on a front of one battalion each, with a battalion advancing to the first objective, one moving through it to the second objective and two more to the final objective, 1,500 yd (1,400 m) beyond the original front line. A map was appended to the Order showing the red, blue and green lines to be captured. A creeping barrage by the five field artillery brigades in the division and bombardments from artillery under corps and army command was described. Special attention was given to mopping-up procedures and the detailing of particular units, to capture selected German strong points.[106]

On 11 September "Divisional Order 32", detailed the march to the divisional assembly area near Ypres and on 14 September "Instruction No. 2" of Order 31, added details of the artillery plan and laid down routes for the approach march. The front line was reconnoitred again on 15 September and signallers began to bury cables 6 ft (1.8 m) deep. "Instruction No. 3" detailed the strong points to be built on captured ground, to accommodate a platoon each, equipment and clothing to conform to Section 31 of SS 135, with an amendment that the battalions on the final objective would carry more ammunition. Coloured patches corresponding to the objective lines were to be worn on helmets and the 1st Australian Infantry Brigade was to be held back, ready to reinforce the attacking brigades or to defeat German counter-attacks. Compasses were issued to officers and white tape was to be used to mark approach routes, jumping-off points and unit boundaries, to help the infantry keep direction. Troops attacking the first objective, were ordered not to fix bayonets until the barrage commenced, to increase the possibility of surprise.[115]

"Instruction No. 4", comprised intelligence instructions for the questioning of prisoners and the gleaning and dissemination of useful information. Men identified by armbands were to scour the battlefield for German documents, using maps of German headquarters, signals offices and dugouts; information was to be sent to a divisional collecting point. "Instruction No. 5" was devoted to liaison, with officers attached to brigades, to report to the divisional commander. Brigades liaised with the other Australian brigades and those of neighbouring divisions, battalions liaising in the same manner. Artillery liaison officers were appointed down to infantry brigades and battalion and company officers were told to keep close to artillery Forward Observation Officers. "Instruction no. 6" covered engineer and pioneer work for the building of strong points, at the places determined in "Divisional Order 31". An Engineer Field Company was attached to each brigade and the Pioneer Battalion was made responsible for the maintenance and extension of communications, including tramways, mule and duckboard tracks and communication trenches. Two supply routes were defined and next day, engineer officers were added to the liaison system within brigade headquarters.[116]