Cholangiocarcinoma

| Cholangiocarcinoma | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Bile duct cancer, cancer of the bile duct[1] |

| |

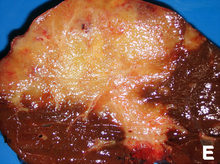

| Micrograph of an intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (right of image) adjacent to normal liver cells (left of image). H&E stain. | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, yellowish skin, weight loss, generalized itching, fever[1] |

| Usual onset | 70 years old[3] |

| Types | Intrahepatic, perihilar, distal[3] |

| Risk factors | Primary sclerosing cholangitis, ulcerative colitis, infection with certain liver flukes, some congenital liver malformations[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Confirmed by examination of the tumor under a microscope[4] |

| Treatment | Surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, stenting procedures, liver transplantation[1] |

| Prognosis | Generally poor[5] |

| Frequency | 1–2 people per 100,000 per year (Western world)[6] |

Cholangiocarcinoma, also known as bile duct cancer, is a type of cancer that forms in the bile ducts.[2] Symptoms of cholangiocarcinoma may include abdominal pain, yellowish skin, weight loss, generalized itching, and fever.[1] Light colored stool or dark urine may also occur.[4] Other biliary tract cancers include gallbladder cancer and cancer of the ampulla of Vater.[7]

Risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma include primary sclerosing cholangitis (an inflammatory disease of the bile ducts), ulcerative colitis, cirrhosis, hepatitis C, hepatitis B, infection with certain liver flukes, and some congenital liver malformations.[1][3][8] However, most people have no identifiable risk factors.[3] The diagnosis is suspected based on a combination of blood tests, medical imaging, endoscopy, and sometimes surgical exploration.[4] The disease is confirmed by examination of cells from the tumor under a microscope.[4] It is typically an adenocarcinoma (a cancer that forms glands or secretes mucin).[3]

Cholangiocarcinoma is typically incurable at diagnosis which is why early detection is ideal.[9][1] In these cases palliative treatments may include surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and stenting procedures.[1] In about a third of cases involving the common bile duct and less commonly with other locations the tumor can be completely removed by surgery offering a chance of a cure.[1] Even when surgical removal is successful chemotherapy and radiation therapy are generally recommended.[1] In certain cases surgery may include a liver transplantation.[3] Even when surgery is successful the 5-year survival is typically less than 50%.[6]

Cholangiocarcinoma is rare in the Western world, with estimates of it occurring in 0.5–2 people per 100,000 per year.[1][6] Rates are higher in Southeast Asia where liver flukes are common.[5] Rates in parts of Thailand are 60 per 100,000 per year.[5] It typically occurs in people in their 70s; however, in those with primary sclerosing cholangitis it often occurs in the 40s.[3] Rates of cholangiocarcinoma within the liver in the Western world have increased.[6]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

The most common physical indications of cholangiocarcinoma are abnormal liver function tests, jaundice (yellowing of the eyes and skin occurring when bile ducts are blocked by tumor), abdominal pain (30–50%), generalized itching (66%), weight loss (30–50%), fever (up to 20%), and changes in the color of stool or urine.[10] To some extent, the symptoms depend upon the location of the tumor: people with cholangiocarcinoma in the extrahepatic bile ducts (outside the liver) are more likely to have jaundice, while those with tumors of the bile ducts within the liver more often have pain without jaundice.[11]

Blood tests of liver function in people with cholangiocarcinoma often reveal a so-called "obstructive picture", with elevated bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and gamma glutamyl transferase levels, and relatively normal transaminase levels. Such laboratory findings suggest obstruction of the bile ducts, rather than inflammation or infection of the liver parenchyma, as the primary cause of the jaundice.[12]

Risk factors

[edit]

Although most people present without any known risk factors evident, a number of risk factors for the development of cholangiocarcinoma have been described. In the Western world, the most common of these is primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), an inflammatory disease of the bile ducts which is closely associated with ulcerative colitis (UC).[13] Epidemiologic studies have suggested that the lifetime risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma for a person with PSC is on the order of 10–15%,[14] although autopsy series have found rates as high as 30% in this population.[15] For inflammatory bowel disease patients with altered DNA repair functions, the progression from PSC to cholangiocarcinoma may be a consequence of DNA damage resulting from biliary inflammation and bile acids.[16]

Certain parasitic liver diseases may be risk factors as well. Colonization with the liver flukes Opisthorchis viverrini (found in Thailand, Laos PDR, and Vietnam)[17][18][19] or Clonorchis sinensis (found in China, Taiwan, eastern Russia, Korea, and Vietnam)[20][21] has been associated with the development of cholangiocarcinoma. Control programs (Integrated Opisthorchiasis Control Program) aimed at discouraging the consumption of raw and undercooked food have been successful at reducing the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma in some countries.[22] People with chronic liver disease, whether in the form of viral hepatitis (e.g. hepatitis B or hepatitis C),[23][24][25] alcoholic liver disease, or cirrhosis of the liver due to other causes, are at significantly increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma.[26][27] HIV infection was also identified in one study as a potential risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma, although it was unclear whether HIV itself or other correlated and confounding factors (e.g. hepatitis C infection) were responsible for the association.[26]

Infection with the bacteria Helicobacter bilis and Helicobacter hepaticus species can cause biliary cancer.[28]

Congenital liver abnormalities, such as Caroli disease (a specific type of five recognized choledochal cysts), have been associated with an approximately 15% lifetime risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma.[29][30] The rare inherited disorders Lynch syndrome II and biliary papillomatosis have also been found to be associated with cholangiocarcinoma.[31][32] The presence of gallstones (cholelithiasis) is not clearly associated with cholangiocarcinoma. However, intrahepatic stones (called hepatolithiasis), which are rare in the West but common in parts of Asia, have been strongly associated with cholangiocarcinoma.[33][34][35] Exposure to Thorotrast, a form of thorium dioxide which was used as a radiologic contrast medium, has been linked to the development of cholangiocarcinoma as late as 30–40 years after exposure; Thorotrast was banned in the United States in the 1950s due to its carcinogenicity.[36][37][38]

Pathophysiology

[edit]

Cholangiocarcinoma can affect any area of the bile ducts, either within or outside the liver. Tumors occurring in the bile ducts within the liver are referred to as intrahepatic, those occurring in the ducts outside the liver are extrahepatic, and tumors occurring at the site where the bile ducts exit the liver may be referred to as perihilar. A cholangiocarcinoma occurring at the junction where the left and right hepatic ducts meet to form the common hepatic duct may be referred to eponymously as a Klatskin tumor.[39]

Although cholangiocarcinoma is known to have the histological and molecular features of an adenocarcinoma of epithelial cells lining the biliary tract, the actual cell of origin is unknown. Recent evidence has suggested that the initial transformed cell that generates the primary tumor may arise from a pluripotent hepatic stem cell.[40][41][42] Cholangiocarcinoma is thought to develop through a series of stages – from early hyperplasia and metaplasia, through dysplasia, to the development of frank carcinoma – in a process similar to that seen in the development of colon cancer.[43] Chronic inflammation and obstruction of the bile ducts, and the resulting impaired bile flow, are thought to play a role in this progression.[43][44][45]

Histologically, cholangiocarcinomas may vary from undifferentiated to well-differentiated. They are often surrounded by a brisk fibrotic or desmoplastic tissue response; in the presence of extensive fibrosis, it can be difficult to distinguish well-differentiated cholangiocarcinoma from normal reactive epithelium. There is no entirely specific immunohistochemical stain that can distinguish malignant from benign biliary ductal tissue, although staining for cytokeratins, carcinoembryonic antigen, and mucins may aid in diagnosis.[46] Most tumors (>90%) are adenocarcinomas.[47]

Diagnosis

[edit]

Blood tests

[edit]There are no specific blood tests that can diagnose cholangiocarcinoma by themselves. Serum levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CA19-9 are often elevated, but are not sensitive or specific enough to be used as a general screening tool. However, they may be useful in conjunction with imaging methods in supporting a suspected diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma.[48]

Abdominal imaging

[edit]

Ultrasound of the liver and biliary tree is often used as the initial imaging modality in people with suspected obstructive jaundice.[49][50] Ultrasound can identify obstruction and ductal dilatation and, in some cases, may be sufficient to diagnose cholangiocarcinoma.[51] Computed tomography (CT) scanning may also play an important role in the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma.[52][53][54]

Imaging of the biliary tree

[edit]

While abdominal imaging can be useful in the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma, direct imaging of the bile ducts is often necessary. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), an endoscopic procedure performed by a gastroenterologist or specially trained surgeon, has been widely used for this purpose. Although ERCP is an invasive procedure with attendant risks, its advantages include the ability to obtain biopsies and to place stents or perform other interventions to relieve biliary obstruction.[12] Endoscopic ultrasound can also be performed at the time of ERCP and may increase the accuracy of the biopsy and yield information on lymph node invasion and operability.[55] As an alternative to ERCP, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) may be utilized. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is a non-invasive alternative to ERCP.[56][57][58] Some authors have suggested that MRCP should supplant ERCP in the diagnosis of biliary cancers, as it may more accurately define the tumor and avoids the risks of ERCP.[59][60][61]

Surgery

[edit]

Surgical exploration may be necessary to obtain a suitable biopsy and to accurately stage a person with cholangiocarcinoma. Laparoscopy can be used for staging purposes and may avoid the need for a more invasive surgical procedure, such as laparotomy, in some people.[62][63]

Pathology

[edit]

Histologically, cholangiocarcinomas are classically well to moderately differentiated adenocarcinomas. Immunohistochemistry is useful in the diagnosis and may be used to help differentiate a cholangiocarcinoma from hepatocellular carcinoma and metastasis of other gastrointestinal tumors.[65] Cytological scrapings are often nondiagnostic,[66] as these tumors typically have a desmoplastic stroma and, therefore, do not release diagnostic tumor cells with scrapings.

Staging

[edit]Although there are at least three staging systems for cholangiocarcinoma (e.g. those of Bismuth, Blumgart, and the American Joint Committee on Cancer), none have been shown to be useful in predicting survival.[67] The most important staging issue is whether the tumor can be surgically removed, or whether it is too advanced for surgical treatment to be successful. Often, this determination can only be made at the time of surgery.[12]

General guidelines for operability include:[68][69]

- Absence of lymph node or liver metastases

- Absence of involvement of the portal vein

- Absence of direct invasion of adjacent organs

- Absence of widespread metastatic disease

Treatment

[edit]Cholangiocarcinoma is considered to be an incurable and rapidly lethal disease unless all the tumors can be fully resected (cut out surgically). Since the operability of the tumor can only be assessed during surgery in most cases,[70] a majority of people undergo exploratory surgery unless there is already a clear indication that the tumor is inoperable.[12] However, the Mayo Clinic has reported significant success treating early bile duct cancer with liver transplantation using a protocolized approach and strict selection criteria.[71]

Adjuvant therapy followed by liver transplantation may have a role in treatment of certain unresectable cases.[72] Locoregional therapies including transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), transarterial radioembolization (TARE) and ablation therapies have a role in intrahepatic variants of cholangiocarcinoma to provide palliation or potential cure in people who are not surgical candidates.[73]

Adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy

[edit]If the tumor can be removed surgically, people may receive adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy after the operation to improve the chances of cure. If the tissue margins are negative (i.e. the tumor has been totally excised), adjuvant therapy is of uncertain benefit. Both positive[74][75] and negative[11][76][77] results have been reported with adjuvant radiation therapy in this setting, and no prospective randomized controlled trials have been conducted as of March 2007. Adjuvant chemotherapy appears to be ineffective in people with completely resected tumors.[78][79] The role of combined chemoradiotherapy in this setting is unclear. However, if the tumor tissue margins are positive, indicating that the tumor was not completely removed via surgery, then adjuvant therapy with radiation and possibly chemotherapy is generally recommended based on the available data.[80] [81]

Treatment of advanced disease

[edit]The majority of cases of cholangiocarcinoma present as inoperable (unresectable) disease[82] in which case people are generally treated with palliative chemotherapy, with or without radiotherapy. Chemotherapy has been shown in a randomized controlled trial to improve quality of life and extend survival in people with inoperable cholangiocarcinoma.[83] There is no single chemotherapy regimen which is universally used, and enrollment in clinical trials is often recommended when possible.[81] Chemotherapy agents used to treat cholangiocarcinoma include 5-fluorouracil with leucovorin,[84] gemcitabine as a single agent,[85] or gemcitabine plus cisplatin,[86] irinotecan,[87] or capecitabine.[88] A small pilot study suggested possible benefit from the tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib in people with advanced cholangiocarcinoma.[89] Radiation therapy appears to prolong survival in people with resected extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma,[90] and the few reports of its use in unresectable cholangiocarcinoma appear to show improved survival, but numbers are small.[6]

Infigratinib (Truseltiq) is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor of fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) that was approved for medical use in the United States in May 2021.[91] It is indicated for the treatment of people with previously treated locally advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma harboring an FGFR2 fusion or rearrangement.[91]

Pemigatinib (Pemazyre) is a kinase inhibitor of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) that was approved for medical use in the United States in April 2020.[92] It is indicated for the treatment of adults with previously treated, unresectable locally advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma with a fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) fusion or other rearrangement as detected by an FDA-approved test.

Ivodesinib (Tibsovo) is a small molecule inhibitor of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1. The FDA approved ivosidenib in August 2021 for adults with previously treated, locally advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma with an isocitrate dehydrogenase-1 (IDH1) mutation as detected by an FDA-approved test.[93]

Durvalumab, (Imfinzi) is an immune checkpoint inhibitor that blocks the PD-L1 protein on the surface of immune cells, thereby allowing the immune system to recognize and attack tumor cells. In Phase III clinical trials, durvalumab, in combination with standard-of-care chemotherapy, demonstrated a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in overall survival and progression-free survival versus chemotherapy alone as a 1st-line treatment for patients with advanced biliary tract cancer.[94]

Futibatinib (Lytgobi) was approved for medical use in the United States in September 2022.[95]

Prognosis

[edit]Surgical resection offers the only potential chance of cure in cholangiocarcinoma. For non-resectable cases, the five-year survival rate is 0% where the disease is inoperable because distal lymph nodes show metastases,[96] and less than 5% in general.[97] Overall mean duration of survival is less than 6 months in people with metastatic disease.[98]

For surgical cases, the odds of cure vary depending on the tumor location and whether the tumor can be completely, or only partially, removed. Distal cholangiocarcinomas (those arising from the common bile duct) are generally treated surgically with a Whipple procedure; long-term survival rates range from 15 to 25%, although one series reported a five-year survival of 54% for people with no involvement of the lymph nodes.[99] Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas (those arising from the bile ducts within the liver) are usually treated with partial hepatectomy. Various series have reported survival estimates after surgery ranging from 22 to 66%; the outcome may depend on involvement of lymph nodes and completeness of the surgery.[100] Perihilar cholangiocarcinomas (those occurring near where the bile ducts exit the liver) are least likely to be operable. When surgery is possible, they are generally treated with an aggressive approach often including removal of the gallbladder and potentially part of the liver. In patients with operable perihilar tumors, reported 5-year survival rates range from 20 to 50%.[101]

The prognosis may be worse for people with primary sclerosing cholangitis who develop cholangiocarcinoma, likely because the cancer is not detected until it is advanced.[15][102] Some evidence suggests that outcomes may be improving with more aggressive surgical approaches and adjuvant therapy.[103]

Epidemiology

[edit]| Country | IC (men/women) | EC (men/women) |

|---|---|---|

| U.S.A. | 0.60/0.43 | 0.70/0.87 |

| Japan | 0.23/0.10 | 5.87/5.20 |

| Australia | 0.70/0.53 | 0.90/1.23 |

| England/Wales | 0.83/0.63 | 0.43/0.60 |

| Scotland | 1.17/1.00 | 0.60/0.73 |

| France | 0.27/0.20 | 1.20/1.37 |

| Italy | 0.13/0.13 | 2.10/2.60 |

Cholangiocarcinoma is a relatively rare form of cancer; each year, approximately 2,000 to 3,000 new cases are diagnosed in the United States, translating into an annual incidence of 1–2 cases per 100,000 people.[105] Autopsy series have reported a prevalence of 0.01% to 0.46%.[82][106] There is a higher prevalence of cholangiocarcinoma in Asia, which has been attributed to endemic chronic parasitic infestation. The incidence of cholangiocarcinoma increases with age, and the disease is slightly more common in men than in women (possibly due to the higher rate of primary sclerosing cholangitis, a major risk factor, in men).[47] The prevalence of cholangiocarcinoma in people with primary sclerosing cholangitis may be as high as 30%, based on autopsy studies.[15]

Multiple studies have documented a steady increase in the incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; increases have been seen in North America, Europe, Asia, and Australia.[107] The reasons for the increasing occurrence of cholangiocarcinoma are unclear; improved diagnostic methods may be partially responsible, but the prevalence of potential risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma, such as HIV infection, has also been increasing during this time frame.[26]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Bile Duct Cancer (Cholangiocarcinoma) Treatment". National Cancer Institute. 23 September 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ^ a b "cholangiocarcinoma". National Cancer Institute. 2 February 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Razumilava N, Gores GJ (June 2014). "Cholangiocarcinoma". Lancet. 383 (9935): 2168–79. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61903-0. PMC 4069226. PMID 24581682.

- ^ a b c d "Bile Duct Cancer (Cholangiocarcinoma)". National Cancer Institute. 5 July 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ a b c Bosman, Frank T. (2014). "Chapter 5.6: Liver cancer". In Stewart, Bernard W.; Wild, Christopher P (eds.). World Cancer Report (PDF). the International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. pp. 403–12. ISBN 978-92-832-0443-5.

- ^ a b c d e Bridgewater JA, Goodman KA, Kalyan A, Mulcahy MF (2016). "Biliary Tract Cancer: Epidemiology, Radiotherapy, and Molecular Profiling". American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Annual Meeting. 35 (36): e194-203. doi:10.1200/EDBK_160831. PMID 27249723.

- ^ Benavides M, Antón A, Gallego J, Gómez MA, Jiménez-Gordo A, La Casta A, et al. (December 2015). "Biliary tract cancers: SEOM clinical guidelines". Clinical & Translational Oncology. 17 (12): 982–7. doi:10.1007/s12094-015-1436-2. PMC 4689747. PMID 26607930.

- ^ Steele JA, Richter CH, Echaubard P, Saenna P, Stout V, Sithithaworn P, et al. (May 2018). "Thinking beyond Opisthorchis viverrini for risk of cholangiocarcinoma in the lower Mekong region: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 7 (1): 44. doi:10.1186/s40249-018-0434-3. PMC 5956617. PMID 29769113.

- ^ Zhang, Tan; Zhang, Sina; Jin, Chen; et al. (2021). "A Predictive Model Based on the Gut Microbiota Improves the Diagnostic Effect in Patients with Cholangiocarcinoma". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 11: 751795. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2021.751795. PMC 8650695. PMID 34888258.

- ^ Nagorney DM, Donohue JH, Farnell MB, Schleck CD, Ilstrup DM (August 1993). "Outcomes after curative resections of cholangiocarcinoma". Archives of Surgery. 128 (8): 871–7, discussion 877–9. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420200045008. PMID 8393652.

- ^ a b Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, Coleman J, Abrams RA, Piantadosi S, et al. (October 1996). "Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors". Annals of Surgery. 224 (4): 463–73, discussion 473–5. doi:10.1097/00000658-199610000-00005. PMC 1235406. PMID 8857851.

- ^ a b c d Mark Feldman; Lawrence S. Friedman; Lawrence J. Brandt, eds. (21 July 2006). Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease (8th ed.). Saunders. pp. 1493–6. ISBN 978-1-4160-0245-1.

- ^ Chapman RW (1999). "Risk factors for biliary tract carcinogenesis". Annals of Oncology. 10 (Suppl 4): 308–11. doi:10.1023/A:1008313809752. PMID 10436847.

- ^ Epidemiologic studies which have addressed the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma in people with primary sclerosing cholangitis include the following:

- Bergquist A, Ekbom A, Olsson R, Kornfeldt D, Lööf L, Danielsson A, et al. (March 2002). "Hepatic and extrahepatic malignancies in primary sclerosing cholangitis". Journal of Hepatology. 36 (3): 321–7. doi:10.1016/S0168-8278(01)00288-4. PMID 11867174.

- Bergquist A, Glaumann H, Persson B, Broomé U (February 1998). "Risk factors and clinical presentation of hepatobiliary carcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: a case-control study". Hepatology. 27 (2): 311–6. doi:10.1002/hep.510270201. PMID 9462625.

- Burak K, Angulo P, Pasha TM, Egan K, Petz J, Lindor KD (March 2004). "Incidence and risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis". American Journal of Gastroenterology. 99 (3): 523–6. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04067.x. PMID 15056096. S2CID 8412954.

- ^ a b c Rosen CB, Nagorney DM, Wiesner RH, Coffey RJ, LaRusso NF (January 1991). "Cholangiocarcinoma complicating primary sclerosing cholangitis". Annals of Surgery. 213 (1): 21–5. doi:10.1097/00000658-199101000-00004. PMC 1358305. PMID 1845927.

- ^ Labib, Peter L.; Goodchild, George; Pereira, Stephen P. (2019). "Molecular Pathogenesis of Cholangiocarcinoma". BMC Cancer. 19 (1): 185. doi:10.1186/s12885-019-5391-0. PMC 6394015. PMID 30819129.

- ^ Watanapa P, Watanapa WB (August 2002). "Liver fluke-associated cholangiocarcinoma". British Journal of Surgery. 89 (8): 962–70. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02143.x. PMID 12153620. S2CID 5606131.

- ^ Sripa B, Kaewkes S, Sithithaworn P, Mairiang E, Laha T, Smout M, et al. (July 2007). "Liver fluke induces cholangiocarcinoma". PLOS Medicine. 4 (7): e201. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040201. PMC 1913093. PMID 17622191.

- ^ Sripa B, Kaewkes S, Intapan PM, Maleewong W, Brindley PJ (2010). Food-borne trematodiases in Southeast Asia epidemiology, pathology, clinical manifestation and control. Vol. 72. pp. 305–50. doi:10.1016/S0065-308X(10)72011-X. ISBN 9780123815132. PMID 20624536.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Rustagi T, Dasanu CA (June 2012). "Risk factors for gallbladder cancer and cholangiocarcinoma: similarities, differences and updates". Journal of Gastrointestinal Cancer. 43 (2): 137–47. doi:10.1007/s12029-011-9284-y. PMID 21597894. S2CID 31590872.

- ^ Hong ST, Fang Y (March 2012). "Clonorchis sinensis and clonorchiasis, an update". Parasitology International. 61 (1): 17–24. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2011.06.007. PMID 21741496.

- ^ Sripa B, Tangkawattana S, Sangnikul T (August 2017). "The Lawa model: A sustainable, integrated opisthorchiasis control program using the EcoHealth approach in the Lawa Lake region of Thailand". Parasitology International. 66 (4): 346–354. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2016.11.013. PMC 5443708. PMID 27890720.

- ^ Kobayashi M, Ikeda K, Saitoh S, Suzuki F, Tsubota A, Suzuki Y, et al. (June 2000). "Incidence of primary cholangiocellular carcinoma of the liver in Japanese patients with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis". Cancer. 88 (11): 2471–7. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(20000601)88:11<2471::AID-CNCR7>3.0.CO;2-T. PMID 10861422. S2CID 22206944.

- ^ Yamamoto S, Kubo S, Hai S, Uenishi T, Yamamoto T, Shuto T, et al. (July 2004). "Hepatitis C virus infection as a likely etiology of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma". Cancer Science. 95 (7): 592–5. doi:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb02492.x. PMC 11158843. PMID 15245596.

- ^ Lu H, Ye MQ, Thung SN, Dash S, Gerber MA (December 2000). "Detection of hepatitis C virus RNA sequences in cholangiocarcinomas in Chinese and American patients". Chinese Medical Journal. 113 (12): 1138–41. PMID 11776153.

- ^ a b c Shaib YH, El-Serag HB, Davila JA, Morgan R, McGlynn KA (March 2005). "Risk factors of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a case-control study". Gastroenterology. 128 (3): 620–6. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.048. PMID 15765398.

- ^ Sorensen HT, Friis S, Olsen JH, Thulstrup AM, Mellemkjaer L, Linet M, et al. (October 1998). "Risk of liver and other types of cancer in patients with cirrhosis: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark". Hepatology. 28 (4): 921–5. doi:10.1002/hep.510280404. PMID 9755226. S2CID 72842845.

- ^ Chang AH, Parsonnet J (October 2010). "Role of bacteria in oncogenesis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 23 (4): 837–57. doi:10.1128/CMR.00012-10. PMC 2952975. PMID 20930075.

- ^ Lipsett PA, Pitt HA, Colombani PM, Boitnott JK, Cameron JL (November 1994). "Choledochal cyst disease. A changing pattern of presentation". Annals of Surgery. 220 (5): 644–52. doi:10.1097/00000658-199411000-00007. PMC 1234452. PMID 7979612.

- ^ Dayton MT, Longmire WP, Tompkins RK (January 1983). "Caroli's Disease: a premalignant condition?". American Journal of Surgery. 145 (1): 41–8. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(83)90164-2. PMID 6295196.

- ^ Mecklin JP, Järvinen HJ, Virolainen M (March 1992). "The association between cholangiocarcinoma and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma". Cancer. 69 (5): 1112–4. doi:10.1002/cncr.2820690508. PMID 1310886. S2CID 23468163.

- ^ Lee SS, Kim MH, Lee SK, Jang SJ, Song MH, Kim KP, et al. (February 2004). "Clinicopathologic review of 58 patients with biliary papillomatosis". Cancer. 100 (4): 783–93. doi:10.1002/cncr.20031. PMID 14770435.

- ^ Lee CC, Wu CY, Chen GH (September 2002). "What is the impact of coexistence of hepatolithiasis on cholangiocarcinoma?". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 17 (9): 1015–20. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02779.x. PMID 12167124. S2CID 25753564.

- ^ Su CH, Shyr YM, Lui WY, P'Eng FK (July 1997). "Hepatolithiasis associated with cholangiocarcinoma". British Journal of Surgery. 84 (7): 969–73. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800840717. PMID 9240138. S2CID 29475282.

- ^ Donato F, Gelatti U, Tagger A, Favret M, Ribero ML, Callea F, et al. (December 2001). "Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and hepatitis C and B virus infection, alcohol intake, and hepatolithiasis: a case-control study in Italy". Cancer Causes & Control. 12 (10): 959–64. doi:10.1023/A:1013747228572. PMID 11808716. S2CID 12117363.

- ^ Sahani D, Prasad SR, Tannabe KK, Hahn PF, Mueller PR, Saini S (2003). "Thorotrast-induced cholangiocarcinoma: case report". Abdominal Imaging. 28 (1): 72–4. doi:10.1007/s00261-001-0148-y. PMID 12483389. S2CID 23531547.

- ^ Zhu AX, Lauwers GY, Tanabe KK (2004). "Cholangiocarcinoma in association with Thorotrast exposure". Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. 11 (6): 430–3. doi:10.1007/s00534-004-0924-5. PMID 15619021.

- ^ Lipshutz GS, Brennan TV, Warren RS (November 2002). "Thorotrast-induced liver neoplasia: a collective review". Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 195 (5): 713–8. doi:10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01287-5. PMID 12437262.

- ^ Klatskin G (February 1965). "Adenocarcinoma of the Hepatic Duct at Its Bifurcation Within The Porta Hepatis. An Unusual Tumor With Distinctive Clinical And Pathological Features". American Journal of Medicine. 38 (2): 241–56. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(65)90178-6. PMID 14256720.

- ^ Roskams T (June 2006). "Liver stem cells and their implication in hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma". Oncogene. 25 (27): 3818–22. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1209558. PMID 16799623.

- ^ Liu C, Wang J, Ou QJ (November 2004). "Possible stem cell origin of human cholangiocarcinoma". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 10 (22): 3374–6. doi:10.3748/wjg.v10.i22.3374. PMC 4572317. PMID 15484322.

- ^ Sell S, Dunsford HA (June 1989). "Evidence for the stem cell origin of hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma". American Journal of Pathology. 134 (6): 1347–63. PMC 1879951. PMID 2474256.

- ^ a b Sirica AE (January 2005). "Cholangiocarcinoma: molecular targeting strategies for chemoprevention and therapy". Hepatology. 41 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1002/hep.20537. PMID 15690474. S2CID 10903371.

- ^ Holzinger F, Z'graggen K, Büchler MW (1999). "Mechanisms of biliary carcinogenesis: a pathogenetic multi-stage cascade towards cholangiocarcinoma". Annals of Oncology. 10 (Suppl 4): 122–6. doi:10.1023/A:1008321710719. PMID 10436802.

- ^ Gores GJ (May 2003). "Cholangiocarcinoma: current concepts and insights". Hepatology. 37 (5): 961–9. doi:10.1053/jhep.2003.50200. PMID 12717374. S2CID 5441766.

- ^ de Groen PC, Gores GJ, LaRusso NF, Gunderson LL, Nagorney DM (October 1999). "Biliary tract cancers". New England Journal of Medicine. 341 (18): 1368–78. doi:10.1056/NEJM199910283411807. PMID 10536130.

- ^ a b Henson DE, Albores-Saavedra J, Corle D (September 1992). "Carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile ducts. Histologic types, stage of disease, grade, and survival rates". Cancer. 70 (6): 1498–501. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19920915)70:6<1498::AID-CNCR2820700609>3.0.CO;2-C. PMID 1516001. S2CID 10348568.

- ^ Studies of the performance of serum markers for cholangiocarcinoma (such as carcinoembryonic antigen and CA19-9) in patients with and without primary sclerosing cholangitis include the following:

- Nehls O, Gregor M, Klump B (May 2004). "Serum and bile markers for cholangiocarcinoma". Seminars in Liver Disease. 24 (2): 139–54. doi:10.1055/s-2004-828891. PMID 15192787. S2CID 260316851.

- Siqueira E, Schoen RE, Silverman W, Martin J, Rabinovitz M, Weissfeld JL, et al. (July 2002). "Detecting cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 56 (1): 40–7. doi:10.1067/mge.2002.125105. PMID 12085033.

- Levy C, Lymp J, Angulo P, Gores GJ, Larusso N, Lindor KD (September 2005). "The value of serum CA 19-9 in predicting cholangiocarcinomas in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 50 (9): 1734–40. doi:10.1007/s10620-005-2927-8. PMID 16133981. S2CID 24744509.

- Patel AH, Harnois DM, Klee GG, LaRusso NF, Gores GJ (January 2000). "The utility of CA 19-9 in the diagnoses of cholangiocarcinoma in patients without primary sclerosing cholangitis". American Journal of Gastroenterology. 95 (1): 204–7. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01685.x. PMID 10638584. S2CID 11325616.

- ^ Saini S (June 1997). "Imaging of the hepatobiliary tract". New England Journal of Medicine. 336 (26): 1889–94. doi:10.1056/NEJM199706263362607. PMID 9197218.

- ^ Sharma MP, Ahuja V (1999). "Aetiological spectrum of obstructive jaundice and diagnostic ability of ultrasonography: a clinician's perspective". Tropical Gastroenterology. 20 (4): 167–9. PMID 10769604.

- ^ Bloom CM, Langer B, Wilson SR (1999). "Role of US in the detection, characterization, and staging of cholangiocarcinoma". Radiographics. 19 (5): 1199–218. doi:10.1148/radiographics.19.5.g99se081199. PMID 10489176.

- ^ Valls C, Gumà A, Puig I, Sanchez A, Andía E, Serrano T, et al. (2000). "Intrahepatic peripheral cholangiocarcinoma: CT evaluation". Abdominal Imaging. 25 (5): 490–6. doi:10.1007/s002610000079. PMID 10931983. S2CID 12010522.

- ^ Tillich M, Mischinger HJ, Preisegger KH, Rabl H, Szolar DH (September 1998). "Multiphasic helical CT in diagnosis and staging of hilar cholangiocarcinoma". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 171 (3): 651–8. doi:10.2214/ajr.171.3.9725291. PMID 9725291.

- ^ Zhang Y, Uchida M, Abe T, Nishimura H, Hayabuchi N, Nakashima Y (1999). "Intrahepatic peripheral cholangiocarcinoma: comparison of dynamic CT and dynamic MRI". Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 23 (5): 670–7. doi:10.1097/00004728-199909000-00004. PMID 10524843.

- ^ Sugiyama M, Hagi H, Atomi Y, Saito M (1997). "Diagnosis of portal venous invasion by pancreatobiliary carcinoma: value of endoscopic ultrasonography". Abdominal Imaging. 22 (4): 434–8. doi:10.1007/s002619900227. PMID 9157867. S2CID 19988847.

- ^ Schwartz LH, Coakley FV, Sun Y, Blumgart LH, Fong Y, Panicek DM (June 1998). "Neoplastic pancreaticobiliary duct obstruction: evaluation with breath-hold MR cholangiopancreatography". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 170 (6): 1491–5. doi:10.2214/ajr.170.6.9609160. PMID 9609160.

- ^ Zidi SH, Prat F, Le Guen O, Rondeau Y, Pelletier G (January 2000). "Performance characteristics of magnetic resonance cholangiography in the staging of malignant hilar strictures". Gut. 46 (1): 103–6. doi:10.1136/gut.46.1.103. PMC 1727781. PMID 10601064.

- ^ Lee MG, Park KB, Shin YM, Yoon HK, Sung KB, Kim MH, et al. (March 2003). "Preoperative evaluation of hilar cholangiocarcinoma with contrast-enhanced three-dimensional fast imaging with steady-state precession magnetic resonance angiography: comparison with intraarterial digital subtraction angiography". World Journal of Surgery. 27 (3): 278–83. doi:10.1007/s00268-002-6701-1. PMID 12607051. S2CID 25092608.

- ^ Yeh TS, Jan YY, Tseng JH, Chiu CT, Chen TC, Hwang TL, et al. (February 2000). "Malignant perihilar biliary obstruction: magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatographic findings". American Journal of Gastroenterology. 95 (2): 432–40. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01763.x. PMID 10685746. S2CID 25350361.

- ^ Freeman ML, Sielaff TD (2003). "A modern approach to malignant hilar biliary obstruction". Reviews in Gastroenterological Disorders. 3 (4): 187–201. PMID 14668691.

- ^ Szklaruk J, Tamm E, Charnsangavej C (October 2002). "Preoperative imaging of biliary tract cancers". Surgical Oncology Clinics of North America. 11 (4): 865–76. doi:10.1016/S1055-3207(02)00032-7. PMID 12607576.

- ^ Weber SM, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Jarnagin WR (March 2002). "Staging laparoscopy in patients with extrahepatic biliary carcinoma. Analysis of 100 patients". Annals of Surgery. 235 (3): 392–9. doi:10.1097/00000658-200203000-00011. PMC 1422445. PMID 11882761.

- ^ Callery MP, Strasberg SM, Doherty GM, Soper NJ, Norton JA (July 1997). "Staging laparoscopy with laparoscopic ultrasonography: optimizing resectability in hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancy". Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 185 (1): 33–9. doi:10.1016/s1072-7515(97)00003-3. PMID 9208958.

- ^ Image by

Mikael Häggström, MD. Source for caption:

- Nat Pernick, M.D. "Cytokeratin 19 (CK19, K19)". Pathology Outlines. Last author update: 1 October 2013 - ^ Länger F, von Wasielewski R, Kreipe HH (July 2006). "[The importance of immunohistochemistry for the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinomas]". Der Pathologe (in German). 27 (4): 244–50. doi:10.1007/s00292-006-0836-z. PMID 16758167. S2CID 7571236.

- ^ Darwin PE, Kennedy A. Cholangiocarcinoma at eMedicine

- ^ Zervos EE, Osborne D, Goldin SB, Villadolid DV, Thometz DP, Durkin A, et al. (November 2005). "Stage does not predict survival after resection of hilar cholangiocarcinomas promoting an aggressive operative approach". American Journal of Surgery. 190 (5): 810–5. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.07.025. PMID 16226963.

- ^ Tsao JI, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, Hayakawa N, Kondo S, Nagino M, et al. (August 2000). "Management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: comparison of an American and a Japanese experience". Annals of Surgery. 232 (2): 166–74. doi:10.1097/00000658-200008000-00003. PMC 1421125. PMID 10903592.

- ^ Rajagopalan V, Daines WP, Grossbard ML, Kozuch P (June 2004). "Gallbladder and biliary tract carcinoma: A comprehensive update, Part 1". Oncology. 18 (7): 889–96. PMID 15255172.

- ^ Su CH, Tsay SH, Wu CC, Shyr YM, King KL, Lee CH, et al. (April 1996). "Factors influencing postoperative morbidity, mortality, and survival after resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma". Annals of Surgery. 223 (4): 384–94. doi:10.1097/00000658-199604000-00007. PMC 1235134. PMID 8633917.

- ^ Rosen CB, Heimbach JK, Gores GJ (2008). "Surgery for cholangiocarcinoma: the role of liver transplantation". HPB. 10 (3): 186–9. doi:10.1080/13651820801992542. PMC 2504373. PMID 18773052.

- ^ Heimbach JK, Gores GJ, Haddock MG, Alberts SR, Pedersen R, Kremers W, et al. (December 2006). "Predictors of disease recurrence following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and liver transplantation for unresectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma". Transplantation. 82 (12): 1703–7. doi:10.1097/01.tp.0000253551.43583.d1. PMID 17198263. S2CID 25466829.

- ^ Kuhlmann JB, Blum HE (May 2013). "Locoregional therapy for cholangiocarcinoma". Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 29 (3): 324–8. doi:10.1097/MOG.0b013e32835d9dea. PMID 23337933. S2CID 37403999.

- ^ Todoroki T, Ohara K, Kawamoto T, Koike N, Yoshida S, Kashiwagi H, et al. (February 2000). "Benefits of adjuvant radiotherapy after radical resection of locally advanced main hepatic duct carcinoma". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 46 (3): 581–7. doi:10.1016/S0360-3016(99)00472-1. PMID 10701737.

- ^ Alden ME, Mohiuddin M (March 1994). "The impact of radiation dose in combined external beam and intraluminal Ir-192 brachytherapy for bile duct cancer". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 28 (4): 945–51. doi:10.1016/0360-3016(94)90115-5. PMID 8138448.

- ^ González González D, Gouma DJ, Rauws EA, van Gulik TM, Bosma A, Koedooder C (1999). "Role of radiotherapy, in particular intraluminal brachytherapy, in the treatment of proximal bile duct carcinoma". Annals of Oncology. 10 (Suppl 4): 215–20. doi:10.1023/A:1008339709327. PMID 10436826.

- ^ Pitt HA, Nakeeb A, Abrams RA, Coleman J, Piantadosi S, Yeo CJ, et al. (June 1995). "Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Postoperative radiotherapy does not improve survival". Annals of Surgery. 221 (6): 788–97, discussion 797–8. doi:10.1097/00000658-199506000-00017. PMC 1234714. PMID 7794082.

- ^ Luvira, V; Satitkarnmanee, E; Pugkhem, A; Kietpeerakool, C; Lumbiganon, P; Pattanittum, P (13 September 2021). "Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable cholangiocarcinoma". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (9): CD012814. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012814.pub2. PMC 8437098. PMID 34515993.

- ^ Takada T, Amano H, Yasuda H, Nimura Y, Matsushiro T, Kato H, et al. (October 2002). "Is postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy useful for gallbladder carcinoma? A phase III multicenter prospective randomized controlled trial in patients with resected pancreaticobiliary carcinoma". Cancer. 95 (8): 1685–95. doi:10.1002/cncr.10831. PMID 12365016.

- ^ "National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines on evaluation and treatment of hepatobiliary malignancies" (PDF). Retrieved 13 March 2007.

- ^ a b "NCCN Guidelines for Patients: Gallbladder and Bile Duct Cancers; Hepatobiliary Cancers" (PDF). National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b Vauthey JN, Blumgart LH (May 1994). "Recent advances in the management of cholangiocarcinomas". Seminars in Liver Disease. 14 (2): 109–14. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1007302. PMID 8047893. S2CID 37111064.

- ^ Glimelius B, Hoffman K, Sjödén PO, Jacobsson G, Sellström H, Enander LK, et al. (August 1996). "Chemotherapy improves survival and quality of life in advanced pancreatic and biliary cancer". Annals of Oncology. 7 (6): 593–600. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a010676. PMID 8879373.

- ^ Choi CW, Choi IK, Seo JH, Kim BS, Kim JS, Kim CD, et al. (August 2000). "Effects of 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin in the treatment of pancreatic-biliary tract adenocarcinomas". American Journal of Clinical Oncology. 23 (4): 425–8. doi:10.1097/00000421-200008000-00023. PMID 10955877.

- ^ Park JS, Oh SY, Kim SH, Kwon HC, Kim JS, Jin-Kim H, et al. (February 2005). "Single-agent gemcitabine in the treatment of advanced biliary tract cancers: a phase II study". Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology. 35 (2): 68–73. doi:10.1093/jjco/hyi021. PMID 15709089.

- ^ Giuliani F, Gebbia V, Maiello E, Borsellino N, Bajardi E, Colucci G (June 2006). "Gemcitabine and cisplatin for inoperable and/or metastatic biliary tree carcinomas: a multicenter phase II study of the Gruppo Oncologico dell'Italia Meridionale (GOIM)". Annals of Oncology. 17 (Suppl 7): vii73–7. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdl956. PMID 16760299.

- ^ Bhargava P, Jani CR, Savarese DM, O'Donnell JL, Stuart KE, Rocha Lima CM (September 2003). "Gemcitabine and irinotecan in locally advanced or metastatic biliary cancer: preliminary report". Oncology. 17 (9 Suppl 8): 23–6. PMID 14569844.

- ^ Knox JJ, Hedley D, Oza A, Feld R, Siu LL, Chen E, et al. (April 2005). "Combining gemcitabine and capecitabine in patients with advanced biliary cancer: a phase II trial". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 23 (10): 2332–8. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.51.008. PMID 15800324.

- ^ Philip PA, Mahoney MR, Allmer C, Thomas J, Pitot HC, Kim G, et al. (July 2006). "Phase II study of erlotinib in patients with advanced biliary cancer". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 24 (19): 3069–74. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3579. PMID 16809731.

- ^ Bonet Beltrán M, Allal AS, Gich I, et al. (2012). "Is adjuvant radiotherapy needed after curative resection of extrahepatic biliary tract cancers? A systematic review with a meta-analysis of observational studies". Cancer Treat Rev. 38 (2): 111–119. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.05.003. PMID 21652148.

- ^ a b "BridgeBio Pharma's Affiliate QED Therapeutics and Partner Helsinn Group Announce FDA Approval of Truseltiq (infigratinib) for Patients with Cholangiocarcinoma" (Press release). BridgeBio Pharma. 28 May 2021. Retrieved 28 May 2021 – via GlobeNewswire.

- ^ "Pemazyre Prescribing Information" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ Research, Center for Drug Evaluation and (1 February 2022). "FDA approves ivosidenib for advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma". FDA.

- ^ "Imfinzi plus chemotherapy reduced risk of death by 20% in 1st-line advanced biliary tract cancer". www.astrazeneca.com. 18 January 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ "FDA Approves Taiho's Lytgobi (futibatinib) Tablets for Previously Treated, Unresectable, Locally Advanced or Metastatic Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma" (Press release). Taiho Oncology. 30 September 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022 – via PR Newswire.

- ^ Yamamoto M, Takasaki K, Yoshikawa T (March 1999). "Lymph node metastasis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma". Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology. 29 (3): 147–50. doi:10.1093/jjco/29.3.147. PMID 10225697.

- ^ Farley DR, Weaver AL, Nagorney DM (May 1995). "'Natural history' of unresected cholangiocarcinoma: patient outcome after noncurative intervention". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 70 (5): 425–9. doi:10.4065/70.5.425. PMID 7537346.

- ^ Grove MK, Hermann RE, Vogt DP, Broughan TA (April 1991). "Role of radiation after operative palliation in cancer of the proximal bile ducts". American Journal of Surgery. 161 (4): 454–8. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(91)91111-U. PMID 1709795.

- ^ Studies of surgical outcomes in distal cholangiocarcinoma include:

- Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, Coleman J, Abrams RA, Piantadosi S, et al. (October 1996). "Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors". Annals of Surgery. 224 (4): 463–73, discussion 473–5. doi:10.1097/00000658-199610000-00005. PMC 1235406. PMID 8857851.

- Jang JY, Kim SW, Park DJ, Ahn YJ, Yoon YS, Choi MG, et al. (January 2005). "Actual long-term outcome of extrahepatic bile duct cancer after surgical resection". Annals of Surgery. 241 (1): 77–84. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000150166.94732.88. PMC 1356849. PMID 15621994.

- Bortolasi L, Burgart LJ, Tsiotos GG, Luque-De León E, Sarr MG (2000). "Adenocarcinoma of the distal bile duct. A clinicopathologic outcome analysis after curative resection". Digestive Surgery. 17 (1): 36–41. doi:10.1159/000018798. PMID 10720830. S2CID 23190342.

- Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Lin E, Fortner JG, Brennan MF (December 1996). "Outcome of treatment for distal bile duct cancer". British Journal of Surgery. 83 (12): 1712–5. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800831217. PMID 9038548. S2CID 30172073.

- ^ Studies of outcome in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma include:

- Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, Coleman J, Abrams RA, Piantadosi S, et al. (October 1996). "Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors". Annals of Surgery. 224 (4): 463–73, discussion 473–5. doi:10.1097/00000658-199610000-00005. PMC 1235406. PMID 8857851.

- Lieser MJ, Barry MK, Rowland C, Ilstrup DM, Nagorney DM (1998). "Surgical management of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a 31-year experience". Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. 5 (1): 41–7. doi:10.1007/PL00009949. PMID 9683753.

- Valverde A, Bonhomme N, Farges O, Sauvanet A, Flejou JF, Belghiti J (1999). "Resection of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a Western experience". Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. 6 (2): 122–7. doi:10.1007/s005340050094. PMID 10398898.

- Nakagohri T, Asano T, Kinoshita H, Kenmochi T, Urashima T, Miura F, et al. (March 2003). "Aggressive surgical resection for hilar-invasive and peripheral intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma". World Journal of Surgery. 27 (3): 289–93. doi:10.1007/s00268-002-6696-7. PMID 12607053. S2CID 25358444.

- Weber SM, Jarnagin WR, Klimstra D, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Blumgart LH (October 2001). "Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: resectability, recurrence pattern, and outcomes". Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 193 (4): 384–91. doi:10.1016/S1072-7515(01)01016-X. PMID 11584966.

- ^ Estimates of survival after surgery for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma include:

- Burke EC, Jarnagin WR, Hochwald SN, Pisters PW, Fong Y, Blumgart LH (September 1998). "Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: patterns of spread, the importance of hepatic resection for curative operation, and a presurgical clinical staging system". Annals of Surgery. 228 (3): 385–94. doi:10.1097/00000658-199809000-00011. PMC 1191497. PMID 9742921.

- Tsao JI, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, Hayakawa N, Kondo S, Nagino M, et al. (August 2000). "Management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: comparison of an American and a Japanese experience". Annals of Surgery. 232 (2): 166–74. doi:10.1097/00000658-200008000-00003. PMC 1421125. PMID 10903592.

- Chamberlain RS, Blumgart LH (2000). "Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a review and commentary". Annals of Surgical Oncology. 7 (1): 55–66. doi:10.1007/s10434-000-0055-4. PMID 10674450. S2CID 19569428.

- Washburn WK, Lewis WD, Jenkins RL (March 1995). "Aggressive surgical resection for cholangiocarcinoma". Archives of Surgery. 130 (3): 270–6. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430030040006. PMID 7534059.

- Nagino M, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, Kanai M, Uesaka K, Hayakawa N, et al. (1998). "Segmental liver resections for hilar cholangiocarcinoma". Hepato-Gastroenterology. 45 (19): 7–13. PMID 9496478.

- Rea DJ, Munoz-Juarez M, Farnell MB, Donohue JH, Que FG, Crownhart B, et al. (May 2004). "Major hepatic resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: analysis of 46 patients". Archives of Surgery. 139 (5): 514–23, discussion 523–5. doi:10.1001/archsurg.139.5.514. PMID 15136352.

- Launois B, Reding R, Lebeau G, Buard JL (2000). "Surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: French experience in a collective survey of 552 extrahepatic bile duct cancers". Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. 7 (2): 128–34. doi:10.1007/s005340050166. PMID 10982604.

- ^ Kaya M, de Groen PC, Angulo P, Nagorney DM, Gunderson LL, Gores GJ, et al. (April 2001). "Treatment of cholangiocarcinoma complicating primary sclerosing cholangitis: the Mayo Clinic experience". American Journal of Gastroenterology. 96 (4): 1164–9. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03696.x. PMID 11316165. S2CID 295347.

- ^ Nakeeb A, Tran KQ, Black MJ, Erickson BA, Ritch PS, Quebbeman EJ, et al. (October 2002). "Improved survival in resected biliary malignancies". Surgery. 132 (4): 555–63, discission 563–4. doi:10.1067/msy.2002.127555. PMID 12407338.

- ^ Khan SA, Taylor-Robinson SD, Toledano MB, Beck A, Elliott P, Thomas HC (December 2002). "Changing international trends in mortality rates for liver, biliary and pancreatic tumours". Journal of Hepatology. 37 (6): 806–13. doi:10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00297-0. PMID 12445422.

- ^ Landis SH, Murray T, Bolden S, Wingo PA (1998). "Cancer statistics, 1998". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 48 (1): 6–29. doi:10.3322/canjclin.48.1.6. PMID 9449931.

- ^ Cancer Statistics Home Page — National Cancer Institute

- ^ Multiple independent studies have documented a steady increase in the worldwide incidence of cholangiocarcinoma. Some relevant journal articles include:

- Patel T (May 2002). "Worldwide trends in mortality from biliary tract malignancies". BMC Cancer. 2: 10. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-2-10. PMC 113759. PMID 11991810.

- Patel T (June 2001). "Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States". Hepatology. 33 (6): 1353–7. doi:10.1053/jhep.2001.25087. PMID 11391522. S2CID 23115927.

- Shaib YH, Davila JA, McGlynn K, El-Serag HB (March 2004). "Rising incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a true increase?". Journal of Hepatology. 40 (3): 472–7. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2003.11.030. PMID 15123362.

- West J, Wood H, Logan RF, Quinn M, Aithal GP (June 2006). "Trends in the incidence of primary liver and biliary tract cancers in England and Wales 1971-2001". British Journal of Cancer. 94 (11): 1751–8. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603127. PMC 2361300. PMID 16736026.

- Khan SA, Taylor-Robinson SD, Toledano MB, Beck A, Elliott P, Thomas HC (December 2002). "Changing international trends in mortality rates for liver, biliary and pancreatic tumours". Journal of Hepatology. 37 (6): 806–13. doi:10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00297-0. PMID 12445422.

- Welzel TM, McGlynn KA, Hsing AW, O'Brien TR, Pfeiffer RM (June 2006). "Impact of classification of hilar cholangiocarcinomas (Klatskin tumors) on the incidence of intra- and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 98 (12): 873–5. doi:10.1093/jnci/djj234. PMID 16788161.

- ^ Table 37.2 in: Sternberg, Stephen (2012). Sternberg's diagnostic surgical pathology. Place of publication not identified: LWW. ISBN 978-1-4511-5289-0. OCLC 953861627.