Double bass

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2020) |

Side and front views of a modern double bass with a French-style bow | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Bass, upright bass, string bass, acoustic bass, acoustic string bass, contrabass, contrabass viol, bass viol, bass violin, standup bass, bull fiddle, doghouse bass, and bass fiddle |

| Classification | String instrument (bowed or plucked) |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 321.322-71 (Composite chordophone sounded by a bow) |

| Developed | 15th–19th century |

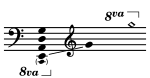

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

| Musicians | |

| Sound sample | |

|

| |

The double bass (/ˈdʌbəl beɪs/), also known as the upright bass, the acoustic bass, the bull fiddle, or simply the bass, is the largest and lowest-pitched chordophone[1] in the modern symphony orchestra (excluding rare additions such as the octobass).[2] Similar in structure to the cello, it has four or five strings.

The bass is a standard member of the orchestra's string section, along with violins, violas, and cellos,[3] as well as the concert band, and is featured in concertos, solo, and chamber music in Western classical music.[4] The bass is used in a range of other genres, such as jazz, blues, rock and roll, rockabilly, country music, bluegrass, tango, folk music and certain types of film and video game soundtracks.

The instrument's exact lineage is still a matter of some debate, with scholars divided on whether the bass is derived from the viol or the violin family.

Being a transposing instrument, the bass is typically notated one octave higher than tuned to avoid excessive ledger lines below the staff. The double bass is the only modern bowed string instrument that is tuned in fourths[5] (like a bass guitar, viol, or the lowest-sounding four strings of a standard guitar), rather than fifths, with strings usually tuned to E1, A1, D2 and G2.

The double bass is played with a bow (arco), or by plucking the strings (pizzicato), or via a variety of extended techniques. In orchestral repertoire and tango music, both arco and pizzicato are employed. In jazz, blues, and rockabilly, pizzicato is the norm. Classical music and jazz use the natural sound produced acoustically by the instrument, as does traditional bluegrass. In funk, blues, reggae, and related genres, the double bass is often amplified.

Terminology

[edit]

A person who plays this instrument is called a "bassist", "double bassist", "double bass player", "contrabassist", "contrabass player" or "bass player". The names contrabass and double bass refer (respectively) to the instrument's range, and to its use one octave lower than the cello (i.e. the cello part was the main bass line, and the "double bass" originally played a copy of the cello part; only later was it given an independent part).[6][7] The terms for the instrument among classical performers are contrabass (which comes from the instrument's Italian name, contrabbasso), string bass (to distinguish it from brass bass instruments in a concert band, such as tubas), or simply bass.

In jazz, blues, rockabilly and other genres outside of classical music, this instrument is commonly called the upright bass, standup bass or acoustic bass to distinguish it from the (usually electric) bass guitar. In folk and bluegrass music, the instrument is also referred to as a "bass fiddle" or "bass violin" (or more rarely as "doghouse bass" or "bull fiddle"[8]). While not a member of the violin-family of instruments, the construction of the upright bass is quite different from that of the acoustic bass guitar, as the latter is a derivative of the electric bass guitar, and usually built like a larger and sturdier variant of a viola de gamba, its ancestor.

The double bass is sometimes confusingly called the violone, bass violin or bass viol.

Description

[edit]

A typical double bass stands around 180 cm (6 feet) from scroll to endpin. Whereas the traditional "full-size" (4⁄4 size) bass stands 74.8 inches (190 cm), the more common 3⁄4 size bass (which has become the most widely used size in the modern era, even among orchestral players) stands 71.6 inches (182 cm) from scroll to endpin.[9][10] Other sizes are also available, such as a 1⁄2 size or 1⁄4 size, which serve to accommodate a player's height and hand size. These names of the sizes do not reflect the true size relative to a "full size" bass; a 1⁄2 bass is not half the length of a 4⁄4 bass, but is only about 15% smaller.[11]

Double basses are typically constructed from several types of wood, including maple for the back, spruce for the top, and ebony for the fingerboard. It is uncertain whether the instrument is a descendant of the viola da gamba or of the violin, but it is traditionally aligned with the violin family. While the double bass is nearly identical in construction to other violin family instruments, it also embodies features found in the older viol family.

The notes of the open strings are E1, A1, D2, and G2, the same as an acoustic or electric bass guitar. However, the resonance of the wood, combined with the violin-like construction and long scale length gives the double bass a much richer tone than the bass guitar, in addition to the ability to use a bow, while the fretless fingerboard accommodates smooth glissandos and legatos.

Playing style

[edit]Like other violin and viol-family string instruments, the double bass is played either with a bow (arco) or by plucking the strings (pizzicato). When employing a bow, the player can either use it traditionally or strike the wood of the bow against the string. In orchestral repertoire and tango music, both arco and pizzicato are employed. In jazz, blues, and rockabilly, pizzicato is the norm, except for some solos and occasional written parts in modern jazz that call for bowing.

Bowed notes in the lowest register of the instrument produce a dark, heavy, mighty, or even menacing effect, when played with a fortissimo dynamic; however, the same low pitches played with a delicate pianissimo can create a sonorous, mellow accompaniment line. Classical bass students learn all of the different bow articulations used by other string section players (e.g., violin and cello), such as détaché, legato, staccato, sforzato, martelé ("hammered"-style), sul ponticello, sul tasto, tremolo, spiccato and sautillé. Some of these articulations can be combined; for example, the combination of sul ponticello and tremolo can produce eerie, ghostly sounds. Classical bass players do play pizzicato parts in orchestra, but these parts generally require simple notes (quarter notes, half notes, whole notes), rather than rapid passages.

Classical players perform both bowed and pizz notes using vibrato, an effect created by rocking or quivering the left hand finger that is contacting the string, which then transfers an undulation in pitch to the tone. Vibrato is used to add expression to string playing. In general, very loud, low-register passages are played with little or no vibrato, as the main goal with low pitches is to provide a clear fundamental bass for the string section. Mid- and higher-register melodies are typically played with more vibrato. The speed and intensity of the vibrato is varied by the performer for an emotional and musical effect.

In jazz, rockabilly and other related genres, much or all of the focus is on playing pizzicato. In jazz and jump blues, bassists are required to play rapid pizzicato walking basslines for extended periods. Jazz and rockabilly bassists develop virtuoso pizzicato techniques that enable them to play rapid solos that incorporate fast-moving triplet and sixteenth note figures. Pizzicato basslines performed by leading jazz professionals are much more difficult than the pizzicato basslines that classical bassists encounter in the standard orchestral literature, which are typically whole notes, half notes, quarter notes, and occasional eighth note passages. In jazz and related styles, bassists often add semi-percussive "ghost notes" into basslines, to add to the rhythmic feel and to add fills to a bassline.

The double bass player stands, or sits on a high stool, and leans the instrument against their body, turned slightly inward to put the strings comfortably in reach. This stance is a key reason for the bass's sloped shoulders, which mark it apart from the other members of the violin family—the narrower shoulders facilitate playing the strings in their higher registers.[10]

History

[edit]

The double bass is generally regarded as a modern descendant of the violone (It. “large viol”), a member of the chordophone family that originated in Europe in the 15th century. [12] Before the 20th century many double basses had only three strings, in contrast to the five to six strings typical of instruments in the viol family or the four strings of instruments in the violin family. The double bass's proportions are dissimilar to those of the violin and cello; for example, it is deeper (the distance from front to back is proportionally much greater than the violin). In addition, while the violin has bulging shoulders, most double basses have shoulders carved with a more acute slope, like members of the viol family. Many very old double basses have had their shoulders cut or sloped to aid playing with modern techniques.[13] Before these modifications, the design of their shoulders was closer to instruments of the violin family.

The double bass is the only modern bowed string instrument that is tuned in fourths (like a viol), rather than fifths (see Tuning below). The instrument's exact lineage is still a matter of some debate, and the supposition that the double bass is a direct descendant of the viol family is one that has not been entirely resolved.

In his A New History of the Double Bass, Paul Brun asserts that the double bass has origins as the true bass of the violin family. He states that, while the exterior of the double bass may resemble the viola da gamba, the internal construction of the double bass is nearly identical to instruments in the violin family, and very different from the internal structure of viols.[14]

Double bass professor Larry Hurst argues that the "modern double bass is not a true member of either the violin or viol families". He says that "most likely its first general shape was that of a violone, the largest member of the viol family. Some of the earliest basses extant are violones, (including C-shaped sound holes) that have been fitted with modern trappings."[15] Some existing instruments, such as those by Gasparo da Salò, were converted from 16th-century six-string contrabass violoni.[4]

Design

[edit]

There are two major approaches to the design outline shape of the double bass: the violin form (shown in the labelled picture in the construction section); and the viola da gamba form (shown in the header picture of this article). A third less common design, called the busetto shape, can also be found, as can the even more rare guitar or pear shape. The back of the instrument can vary from being a round, carved back similar to that of the violin, to a flat and angled back similar to the viol family.

The double bass features many parts that are similar to members of the violin family, including a wooden, carved bridge to support the strings, two f-holes, a tailpiece into which the ball ends of the strings are inserted (with the tailpiece anchored around the endpin mount), an ornamental scroll near the pegbox, a nut with grooves for each string at the junction of the fingerboard and the pegbox and a sturdy, thick sound post, which transmits the vibrations from the top of the instrument to the hollow body and supports the pressure of the string tension. Unlike the rest of the violin family, the double bass still reflects influences, and can be considered partly derived, from the viol family of instruments, in particular the violone, the lowest-pitched and largest bass member of the viol family. For example, the bass is tuned in fourths, like a viol, rather than in fifths, which is the standard in the violin group. Also, notice that the 'shoulders' meet the neck in a curve, rather than the sharp angle seen among violins. As with the other violin and viol family instruments that are played with a bow (and unlike mainly plucked or picked instruments like guitar), the double bass's bridge has an arc-like, curved shape. This is done because with bowed instruments, the player must be able to play individual strings. If the double bass were to have a flat bridge, it would be impossible to bow the A and D strings individually.

The double bass also differs from members of the violin family in that the shoulders are typically sloped and the back is often angled (both to allow easier access to the instrument, particularly in the upper range). Machine tuners are always fitted, in contrast to the rest of the violin family, where traditional wooden friction pegs are still the primary means of tuning. Lack of standardization in design means that one double bass can sound and look very different from another.

Construction

[edit]The double bass is closest in construction to violins, but has some notable similarities to the violone, the largest and lowest-pitched member of the viol family. Unlike the violone, however, the fingerboard of the double bass is unfretted, and the double bass has fewer strings (the violone, like most viols, generally had six strings, although some specimens had five or four). The fingerboard is made of ebony on high-quality instruments; on less expensive student instruments, other woods may be used and then painted or stained black (a process called "ebonizing"). The fingerboard is radiused using a curve, for the same reason that the bridge is curved: if the fingerboard and bridge were to be flat, then a bassist would not be able to bow the inner two strings individually. By using a curved bridge and a curved fingerboard, the bassist can align the bow with any of the four strings and play them individually. Unlike the violin and viola, but like the cello, the bass fingerboard is somewhat flattened out underneath the E string (the C string on cello), this is commonly known as a Romberg bevel. The vast majority of fingerboards cannot be adjusted by the performer; any adjustments must be made by a luthier. A very small number of expensive basses for professionals have adjustable fingerboards, in which a screw mechanism can be used to raise or lower the fingerboard height.

An important distinction between the double bass and other members of the violin family is the construction of the pegbox and the tuning mechanism. While the violin, viola, and cello all use friction pegs for tuning adjustments (tightening and loosening the string tension to raise or lower the string's pitch), the double bass has metal machine heads and gears. One of the challenges with tuning pegs is that the friction between the wood peg and the peg hole may become insufficient to hold the peg in place, particularly if the peg hole become worn and enlarged. The key on the tuning machine of a double bass turns a metal worm, which drives a worm gear that winds the string. Turning the key in one direction tightens the string (thus raising its pitch); turning the key the opposite direction reduces the tension on the string (thus lowering its pitch). While this development makes fine tuners on the tailpiece (important for violin, viola and cello players, as their instruments use friction pegs for major pitch adjustments) unnecessary, a very small number of bassists use them nevertheless. One rationale for using fine tuners on bass is that for instruments with the low C extension, the pulley system for the long string may not effectively transfer turns of the key into changes of string tension/pitch. At the base of the double bass is a metal rod with a spiked or rubberized end called the endpin, which rests on the floor. This endpin is generally thicker and more robust than that of a cello, because of the greater mass of the instrument.

The materials most often used in double bass construction for fully carved basses (the type used by professional orchestra bassists and soloists) are maple (back, neck, ribs), spruce (top), and ebony (fingerboard, tailpiece). The tailpiece may be made from other types of wood or non-wood materials. Less expensive basses are typically constructed with laminated (plywood) tops, backs, and ribs, or are hybrid models produced with laminated backs and sides and carved solid wood tops. Some 2010-era lower- to mid-priced basses are made of willow, student models constructed of Fiberglass were produced in the mid-20th century, and some (typically fairly expensive) basses have been constructed of carbon fiber.

Laminated (plywood) basses, which are widely used in music schools, youth orchestras, and in popular and folk music settings (including rockabilly, psychobilly, blues, etc.), are very resistant to humidity and heat, as well to the physical abuse they are apt to encounter in a school environment (or, for blues and folk musicians, to the hazards of touring and performing in bars). Another option is the hybrid body bass, which has a laminated back and a carved or solid wood top. It is less costly and somewhat less fragile (at least regarding its back) than a fully carved bass.

The soundpost and bass bar are components of the internal construction. All the parts of a double bass are glued together, except the soundpost, bridge, and tailpiece, which are held in place by string tension (although the soundpost usually remains in place when the instrument's strings are loosened or removed, as long as the bass is kept on its back. Some luthiers recommend changing only one string at a time to reduce the risk of the soundpost falling). If the soundpost falls, a luthier is needed to put the soundpost back into position, as this must be done with tools inserted into the f-holes; moreover, the exact placement of the soundpost under the bridge is essential for the instrument to sound its best. Basic bridges are carved from a single piece of wood, which is customized to match the shape of the top of each instrument. The least expensive bridges on student instruments may be customized just by sanding the feet to match the shape of the instrument's top. A bridge on a professional bassist's instrument may be ornately carved by a luthier.

Professional bassists are more likely to have adjustable bridges, which have a metal screw mechanism. This enables the bassist to raise or lower the height of the strings to accommodate changing humidity or temperature conditions.[16] The metal tuning machines are attached to the sides of the pegbox with metal screws. While tuning mechanisms generally differ from the higher-pitched orchestral stringed instruments, some basses have non-functional, ornamental tuning pegs projecting from the side of the pegbox, in imitation of the tuning pegs on a cello or violin.[17]

Travel instruments

[edit]Several manufacturers make travel instruments, which are double basses that have features which reduce the size of the instrument so that the instrument will meet airline travel requirements. Travel basses are designed for touring musicians. One type of travel bass has a much smaller body than normal, while still retaining all of the features needed for playing. While these smaller-body instruments appear similar to electric upright basses, the difference is that small-body travel basses still have a fairly large hollow acoustic sound chamber, while many EUBs are solid body, or only have a small hollow chamber. A second type of travel bass has a hinged or removable neck and a regular sized body. The hinged or removable neck makes the instrument smaller when it is packed for transportation.

Strings

[edit]

The history of the double bass is tightly coupled to the development of string technology, as it was the advent[6] of overwound gut strings, which first rendered the instrument more generally practicable, as wound or overwound strings attain low notes within a smaller overall string diameter than non-wound strings.[18] Professor Larry Hurst argues that had "it not been for the appearance of the overwound gut string in the 1650s, the double bass would surely have become extinct",[15] because thicknesses needed for regular gut strings made the lower-pitched strings almost unplayable and hindered the development of fluid, rapid playing in the lower register.

Prior to the 20th century, double bass strings were usually made of catgut; however, steel has largely replaced it, because steel strings hold their pitch better and yield more volume when played with the bow.[19][20][21] Gut strings are also more vulnerable to changes of humidity and temperature, and break more easily than steel strings.

Gut strings are nowadays mostly used by bassists who perform in baroque ensembles, rockabilly bands, traditional blues bands, and bluegrass bands. In some cases, the low E and A are wound in silver, to give them added mass. Gut strings provide the dark, "thumpy" sound heard on 1940s and 1950s recordings. The late Jeff Sarli, a blues upright bassist, said that "Starting in the 1950s, they began to reset the necks on basses for steel strings."[22] Rockabilly and bluegrass bassists also prefer gut because it is much easier to perform the "slapping" upright bass style (in which the strings are percussively slapped and clicked against the fingerboard) with gut strings than with steel strings, because gut does not hurt the plucking fingers as much. A less expensive alternative to gut strings is nylon strings; the higher strings are pure nylon, and the lower strings are nylon wrapped in wire, to add more mass to the string, slowing the vibration, and thus facilitating lower pitches.

The change from gut to steel has also affected the instrument's playing technique over the last hundred years. Steel strings can be set up closer to the fingerboard and, additionally, strings can be played in higher positions on the lower strings and still produce clear tone. The classic 19th century Franz Simandl method does not use the low E string in higher positions because older gut strings, set up high over the fingerboard, could not produce clear tone in these higher positions. However, with modern steel strings, bassists can play with clear tone in higher positions on the low E and A strings, particularly when they use modern lighter-gauge, lower-tension steel strings.

Bows

[edit]The double bass bow comes in two distinct forms (shown below). The "French" or "overhand" bow is similar in shape and implementation to the bow used on the other members of the orchestral string instrument family, while the "German" or "Butler" bow is typically broader and shorter, and is held in a "hand shake" (or "hacksaw") position.

These two bows provide different ways of moving the arm and distributing force and weight on the strings. Proponents of the French bow argue that it is more maneuverable, due to the angle at which the player holds the bow. Advocates of the German bow claim that it allows the player to apply more arm weight on the strings. The differences between the two, however, are minute for a proficient player, and modern players in major orchestras use both bows.

German bow

[edit]

The German bow (sometimes called the Butler bow) is the older of the two designs. The design of the bow and the manner of holding it descend from the older viol instrument family. With older viols, before frogs had screw threads to tighten the bow, players held the bow with two fingers between the stick and the hair to maintain tension of the hair.[23] Proponents of the use of German bow claim that the German bow is easier to use for heavy strokes that require a lot of power.

Compared to the French bow, the German bow has a taller frog, and the player holds it with the palm angled upwards, as with the upright members of the viol family. When held in the traditionally correct manner, the thumb applies the necessary power to generate the desired sound. The index finger meets the bow at the point where the frog meets the stick. The index finger also applies an upward torque to the frog when tilting the bow. The little finger (or "pinky") supports the frog from underneath, while the ring finger and middle finger rest in the space between the hair and the shaft.

French bow

[edit]

The French bow was not widely popular until its adoption by 19th-century virtuoso Giovanni Bottesini. This style is more similar to the traditional bows of the smaller string family instruments. It is held as if the hand is resting by the side of the performer with the palm facing toward the bass. The thumb rests on the shaft of the bow, next to the frog while the other fingers drape on the other side of the bow. Various styles dictate the curve of the fingers and thumb, as do the style of piece; a more pronounced curve and lighter hold on the bow is used for virtuoso or more delicate pieces, while a flatter curve and sturdier grip on the bow sacrifices some power for easier control in strokes such as detaché, spiccato, and staccato.

Bow construction and materials

[edit]Double bass bows vary in length, ranging from 60 to 75 cm (24–30 in). In general, a bass bow is shorter and heavier than a cello bow. Pernambuco, also known as Brazilwood, is regarded as an excellent quality stick material, but due to its scarcity and expense, other materials are increasingly being used. Inexpensive student bows may be constructed of solid fiberglass, which makes the bow much lighter than a wooden bow (even too light to produce a good tone, in some cases). Student bows may also be made of the less valuable varieties of brazilwood. Snakewood and carbon fiber are also used in bows of a variety of different qualities. The frog of the double bass bow is usually made out of ebony, although snakewood and buffalo horn are used by some luthiers. The frog is movable, as it can be tightened or loosened with a knob (like all violin family bows). The bow is loosened at the end of a practice session or performance. The bow is tightened before playing, until it reaches a tautness that is preferred by the player. The frog on a quality bow is decorated with mother of pearl inlay.

Bows have a leather wrapping on the wooden part of the bow near the frog. Along with the leather wrapping, there is also a wire wrapping, made of silver in quality bows. The hair is usually horsehair. Part of the regular maintenance of a bow is having the bow "rehaired" by a luthier with fresh horsehair and having the leather and wire wrapping replaced. The double bass bow is strung with either white or black horsehair, or a combination of the two (known as "salt and pepper"), as opposed to the customary white horsehair used on the bows of other string instruments. Some of the lowest-quality, lowest cost student bows are made with synthetic hair. Synthetic hair does not have the tiny "barbs" that real horsehair has, so it does not "grip" the string well or take rosin well.

Rosin

[edit]

String players apply rosin to the bow hair so it "grips" the string and makes it vibrate. Double bass rosin is generally softer and stickier than violin rosin to allow the hair to grab the thicker strings better, but players use a wide variety of rosins that vary from quite hard (like violin rosin) to quite soft, depending on the weather, the humidity, and the preference of the player. The amount used generally depends on the type of music being performed as well as the personal preferences of the player. Some brands of rosin, such as Wiedoeft or Pop's double bass rosin, are softer and more prone to melting in hot weather.

Mechanism of sound production

[edit]Owing to their relatively small diameters, the strings themselves do not move much air and therefore cannot produce much sound on their own. The vibrational energy of the strings must somehow be transferred to the surrounding air. To do this, the strings vibrate the bridge and this in turn vibrates the top surface. Very small amplitude but relatively large force variations (due to the cyclically varying tension in the vibrating string) at the bridge are transformed to larger amplitude ones by combination of bridge and body of the bass. The bridge transforms the high force, small amplitude vibrations to lower force higher amplitude vibrations on the top of the bass body. The top is connected to the back by means of a sound post, so the back also vibrates. Both the front and back transmit the vibrations to the air and act to match the impedance of the vibrating string to the acoustic impedance of the air.

Specific sound and tone production mechanism

[edit]Because the acoustic bass is a non-fretted instrument, any string vibration due to plucking or bowing will cause an audible sound due to the strings vibrating against the fingerboard near to the fingered position. This buzzing sound gives the note its character.

Pitch

[edit]

The lowest note of a double bass is an E1 (on standard four-string basses) at approximately 41 Hz or a C1 (≈33 Hz), or sometimes B0 (≈31 Hz), when five strings are used. This is within about an octave above the lowest frequency that the average human ear can perceive as a distinctive pitch. The top of the instrument's fingerboard range is typically near D5, two octaves and a fifth above the open pitch of the G string (G2), as shown in the range illustration found at the head of this article. Playing beyond the end of the fingerboard can be accomplished by pulling the string slightly to the side.

Double bass symphony parts sometimes indicate that the performer should play harmonics (also called flageolet tones), in which the bassist lightly touches the string–without pressing it onto the fingerboard in the usual fashion–in the location of a note and then plucks or bows the note. Bowed harmonics are used in contemporary music for their "glassy" sound. Both natural harmonics and artificial harmonics, where the thumb stops the note and the octave or other harmonic is activated by lightly touching the string at the relative node point, extend the instrument's range considerably. Natural and artificial harmonics are used in plenty of virtuoso concertos for the double bass.

Orchestral parts from the standard Classical repertoire rarely demand the double bass exceed a two-octave and a minor third range, from E1 to G3, with occasional A3s appearing in the standard repertoire (an exception to this rule is Orff's Carmina Burana, which calls for three octaves and a perfect fourth). The upper limit of this range is extended a great deal for 20th- and 21st-century orchestral parts (e.g., Prokofiev's Lieutenant Kijé Suite (c.1933) bass solo, which calls for notes as high as D4 and E♭4). The upper range a virtuoso solo player can achieve using natural and artificial harmonics is hard to define, as it depends on the skill of the particular player. The high harmonic in the range illustration found at the head of this article may be taken as representative rather than normative.

Five-string instruments have an additional string, typically tuned to a low B below the E string (B0). On rare occasions, a higher string is added instead, tuned to the C above the G string (C3). Four-string instruments may feature the C extension extending the range of the E string downwards to C1 (sometimes B0).

Traditionally, the double bass is a transposing instrument. Since much of the double bass's range lies below the standard bass clef, it is notated an octave higher than it sounds to avoid having to use excessive ledger lines below the staff. Thus, when double bass players and cellists are playing from a combined bass-cello part, as used in many Mozart and Haydn symphonies, they will play in octaves, with the basses one octave below the cellos. This transposition applies even when bass players are reading the tenor and treble clef (which are used in solo playing and some orchestral parts). The tenor clef is also used by composers for cello and low brass parts. The use of tenor or treble clef avoids excessive ledger lines above the staff when notating the instrument's upper range. Other notation traditions exist. Italian solo music is typically written at the sounding pitch, and the "old" German method sounded an octave below where notation except in the treble clef, where the music was written at pitch.

Tuning

[edit]Regular tuning

[edit]

The double bass is generally tuned in fourths, in contrast to other members of the orchestral string family, which are tuned in fifths (for example, the violin's four strings are, from lowest-pitched to highest-pitched: G–D–A–E). The standard tuning (lowest-pitched to highest-pitched) for bass is E–A–D–G, starting from E below second low C (concert pitch). This is the same as the standard tuning of a bass guitar and is one octave lower than the four lowest-pitched strings of standard guitar tuning. Prior to the 19th-century, many double basses had only three strings; "Giovanni Bottesini (1821–1889) favored the three-stringed instrument popular in Italy at the time",[15] because "the three-stringed instrument [was viewed as] being more sonorous".[24] Many cobla bands in Catalonia still have players using traditional three-string double basses tuned A–D–G.[25]

Throughout classical repertoire, there are notes that fall below the range of a standard double bass. Notes below low E appear regularly in the double bass parts found in later arrangements and interpretations of Baroque music. In the Classical era, the double bass typically doubled the cello part an octave below, occasionally requiring descent to C below the E of the four-string double bass. In the Romantic era and the 20th century, composers such as Wagner, Mahler, Busoni and Prokofiev also requested notes below the low E.

There are several methods for making these notes available to the player. Players with standard double basses (E–A–D–G) may play the notes below "E" an octave higher or if this sounds awkward, the entire passage may be transposed up an octave. The player may tune the low E string down to the lowest note required in the piece: D or C. Four-string basses may be fitted with a "low-C extension" (see below). Or the player may employ a five-string instrument, with the additional lower string tuned to C, or (more commonly in modern times) B, three octaves and a semitone below middle C. Several major European orchestras use basses with a fifth string.[26]

C extension

[edit]

Most professional orchestral players use four-string double basses with a C extension.[27] This is an extra section of fingerboard mounted on the head of the bass. It extends the fingerboard under the lowest string and gives an additional four semitones of downward range. The lowest string is typically tuned down to C1, an octave below the lowest note on the cello (as it is quite common for a bass part to double the cello part an octave lower). More rarely this string may be tuned to a low B0, as a few works in the orchestral repertoire call for such a B, such as Respighi's The Pines of Rome. In rare cases, some players have a low B extension, which has B as its lowest note. There are several varieties of extensions:

In the simplest mechanical extensions, there are no mechanical aids attached to the fingerboard extension except a locking nut or "gate" for the E note. To play the extension notes, the player reaches back over the area under the scroll to press the string to the fingerboard. The advantage of this "fingered" extension is that the player can adjust the intonation of all of the stopped notes on the extension, and there are no mechanical noises from metal keys and levers. The disadvantage of the "fingered" extension is that it can be hard to perform rapid alternations between low notes on the extension and notes on the regular fingerboard, such as a bassline that quickly alternates between G1 and D1.

The simplest type of mechanical aid is the use of wooden "fingers" or "gates" that can be closed to press the string down and fret the C♯, D, E♭, or E notes. This system is particularly useful for basslines that have a repeating pedal point such as a low D because once the note is locked in place with the mechanical finger the lowest string sounds a different note when played open.

The most complicated mechanical aid for use with extensions is the mechanical lever system nicknamed the machine. This lever system, which superficially resembles the keying mechanism of reed instruments such as the bassoon, mounts levers beside the regular fingerboard (near the nut, on the E-string side), which remotely activate metal "fingers" on the extension fingerboard. The most expensive metal lever systems also give the player the ability to "lock" down notes on the extension fingerboard, as with the wooden "finger" system. One criticism of these devices is that they may lead to unwanted metallic clicking noises.

Once a mechanical "finger" of the wooden "finger" extension or the metal "finger" machine extension is locked down or depressed, it is not easy to make microtonal pitch adjustments or glissando effects, as is possible with a hand-fingered extension.

Five-string basses, in which the lowest string is normally B0, may use either a two semitone extension, providing a low A, or the very rare low G extension.

Other tuning variations

[edit]A small number of bass players tune their strings in fifths, like a cello but an octave lower (C1–G1–D2–A2 low to high). This tuning was used by the jazz player Red Mitchell and is used by some classical players, notably the Canadian bassist Joel Quarrington. Advocates of tuning the bass in fifths point out that all of the other orchestral strings are tuned in fifths (violin, viola, and cello), so this puts the bass in the same tuning approach. Fifth tuning provides a bassist with a wider range of pitch than a standard E–A–D–G bass, as it ranges (without an extension) from C1 to A2. Some players who use fifths tuning who play a five-string bass use an additional high E3 string (thus, from lowest to highest: C–G–D–A–E). Some fifth tuning bassists who only have a four string instrument and who are mainly performing soloistic works use the G–D–A–E tuning, thus omitting the low C string but gaining a high E. Some fifth tuning bassists who use a five-string use a smaller scale instrument, thus making fingering somewhat easier. The Berlioz–Strauss Treatise on Instrumentation (first published in 1844) states that "A good orchestra should have several four-string double-basses, some of them tuned in fifths and thirds." The book then shows a tuning of E1–G1–D2–A2) from bottom to top string. "Together with the other double-basses tuned in fourths, a combination of open strings would be available, which would greatly increase the sonority of the orchestra."

In classical solo playing the double bass is usually tuned a whole tone higher (F♯1–B1–E2–A2). This higher tuning is called "solo tuning", whereas the regular tuning is known as "orchestral tuning". Solo tuning strings are generally thinner than regular strings. String tension differs so much between solo and orchestral tuning that a different set of strings is often employed that has a lighter gauge. Strings are always labelled for either solo or orchestral tuning and published solo music is arranged for either solo or orchestral tuning. Some popular solos and concerti, such as the Koussevitsky Concerto are available in both solo and orchestral tuning arrangements. Solo tuning strings can be tuned down a tone to play in orchestra pitch, but the strings often lack projection in orchestral tuning and their pitch may be unstable.

Some contemporary composers specify highly specialized scordatura (intentionally changing the tuning of the open strings). Changing the pitch of the open strings makes different notes available as pedal points and harmonics. A variant and much less-commonly used form of solo tuning used in some Eastern European countries is (A1–D2–G2–C3), which omits the low E string from orchestral tuning and then adds a high C string. The tololoche in Mexico (a smaller variant of the double bass) also uses the A-D-G-C tuning. Some bassists with five-string basses use a high C3 string as the fifth string, instead of a low B0 string. Adding the high C string facilitates the performance of solo repertoire with a high tessitura (range). Another option is to utilize both a low C (or low B) extension and a high C string.

Five strings

[edit]When choosing a bass with a fifth string, the player may decide between adding a higher-pitched string (a high C string) or a lower-pitched string (typically a low B). To accommodate the additional fifth string, the fingerboard is usually slightly widened, and the top slightly thicker, to handle the increased tension. Most five-string basses are therefore larger in size than a standard four-string bass. Some five-stringed instruments are converted four-string instruments. Because these do not have wider fingerboards, some players find them more difficult to finger and bow. Converted four-string basses usually require either a new, thicker top, or lighter strings to compensate for the increased tension.

Six strings

[edit]The six-string double bass has both a high C and a low B, making it very useful, and it is becoming more practical after several updates. It is ideal for solo and orchestral playing because it has a more playable range. This can be achieved on a six-string violone in D by restringing it with double bass strings, making the tuning B0–E1–A1–D2–G2–C3.

Playing and performance considerations

[edit]Body and hand position

[edit]

Double bassists either stand or sit to play the instrument. The instrument height is set by adjusting the endpin such that the player can reach the desired playing zones of the strings with bow or plucking hand. Bassists who stand and bow sometimes set the endpin by aligning the first finger in either first or half position with eye level, although there is little standardization in this regard. Players who sit generally use a stool about the height of the player's trousers inseam length.

Traditionally, double bassists stood to play solo and sat to play in the orchestra or opera pit. Now, it is unusual for a player to be equally proficient in both positions, so some soloists sit (as with Joel Quarrington, Jeff Bradetich, Thierry Barbé, and others) and some orchestral bassists stand.

When playing in the instrument's upper range (above G3, the G below middle C), the player shifts the hand from behind the neck and flattens it out, using the side of the thumb to press down the string. This technique—also used on the cello—is called thumb position. While playing in thumb position, few players use the fourth (little) finger, as it is usually too weak to produce reliable tone (this is also true for cellists), although some extreme chords or extended techniques, especially in contemporary music, may require its use.

Physical considerations

[edit]Rockabilly style can be very demanding on the plucking hand, due to rockabilly's use of "slapping" on the fingerboard. Performing on bass can be physically demanding, because the strings are under relatively high tension. Also, the space between notes on the fingerboard is large, due to scale length and string spacing, so players must hold their fingers apart for the notes in the lower positions and shift positions frequently to play basslines. As with all non-fretted string instruments, performers must learn to place their fingers precisely to produce the correct pitch. For bassists with shorter arms or smaller hands, the large spaces between pitches may present a significant challenge, especially in the lowest range, where the spaces between notes are largest. However, the increased use of playing techniques such as thumb position and modifications to the bass, such as the use of lighter-gauge strings at lower tension, have eased the difficulty of playing the instrument.

Bass parts have relatively fewer fast passages, double stops, or large jumps in range. These parts are usually given to the cello section, since the cello is a smaller instrument on which these techniques are more easily performed.

Volume

[edit]Despite the size of the instrument, it is not as loud as many other instruments, due to its low musical pitch. In a large orchestra, usually between four and eight bassists play the same bassline in unison to produce enough volume. In the largest orchestras, bass sections may have as many as ten or twelve players, but modern budget constraints make bass sections this large unusual.

When writing solo passages for the bass in orchestral or chamber music, composers typically ensure the orchestration is light so it does not obscure the bass. While amplification is rarely used in classical music, in some cases where a bass soloist performs a concerto with a full orchestra, subtle amplification called acoustic enhancement may be used. The use of microphones and amplifiers in a classical setting has led to debate within the classical community, as "...purists maintain that the natural acoustic sound of [Classical] voices [or] instruments in a given hall should not be altered".[28]

In many genres, such as jazz and blues, players use amplification via a specialized amplifier and loudspeakers. A piezoelectric pickup connects to the amplifier with a 1⁄4-inch cable. Bluegrass and jazz players typically use less amplification than blues, psychobilly, or jam band players. In the latter cases, high overall volume from other amplifiers and instruments may cause unwanted acoustic feedback, a problem exacerbated by the bass's large surface area and interior volume. The feedback problem has led to technological fixes like electronic feedback eliminator devices (essentially an automated notch filter that identifies and reduces frequencies where feedback occurs) and instruments like the electric upright bass, which has playing characteristics like the double bass but usually little or no soundbox, which makes feedback less likely. Some bassists reduce the problem of feedback by lowering their onstage volume or playing further away from their bass amp speakers.

In rockabilly and psychobilly, percussively slapping the strings against the fingerboard is an important part of the bass playing style. Since piezoelectric pickups are not good at reproducing the sounds of strings being slapped against the fingerboard, bassists in these genres often use both piezoelectric pickups (for the low bass tone) and a miniature condenser mic (to pick up the percussive slapping sounds). These two signals are blended together using a simple mixer before the signal is sent to the bass amp.

Transportation

[edit]The double bass's large size and relative fragility make it cumbersome to handle and transport. Most bassists use soft cases, referred to as gig bags, to protect the instrument during transport. These range from inexpensive, thin unpadded cases used by students (which only protect against scratches and rain) to thickly padded versions for professional players, which also protect against bumps and impacts. Some bassists carry their bow in a hard bow case; more expensive bass cases have a large pocket for a bow case. Players also may use a small cart and end pin-attached wheels to move the bass. Some higher-priced padded cases have wheels attached to the case. Another option found in higher-priced padded cases are backpack straps, to make it easier to carry the instrument.

Hard flight cases have cushioned interiors and tough exteriors of carbon fiber, graphite, fiberglass, or Kevlar. The cost of good hard cases–several thousand US dollars–and the high airline fees for shipping them tend to limit their use to touring professionals.

Accessories

[edit]

Double bass players use various accessories to help them to perform and rehearse. Three types of mutes are used in orchestral music: a wooden mute that slides onto the bridge, a rubber mute that attaches to the bridge and a wire device with brass weights that fits onto the bridge. The player uses the mute when the Italian instruction con sordino ("with mute") appears in the bass part, and removes it in response to the instruction senza sordino ("without mute"). With the mute on, the tone of the bass is quieter, darker, and more somber. Bowed bass parts with a mute can have a nasal tone. Players use a third type of mute, a heavy rubber practice mute, to practice quietly without disturbing others (e.g., in a hotel room).

A quiver is an accessory for holding the bow. It is often made of leather and it attaches to the bridge and tailpiece with ties or straps. It is used to hold the bow while a player plays pizzicato parts.

A wolf tone eliminator is used to lessen unwanted sympathetic vibrations in the part of a string between the bridge and the tailpiece which can cause tone problems for certain notes. It is a rubber tube cut down the side that is used with a cylindrical metal sleeve which also has a slot on the side. The metal cylinder has a screw and a nut that fastens the device to the string. Different placements of the cylinder along the string influence or eliminate the frequency at which the wolf tone occurs. It is essentially an attenuator that slightly shifts the natural frequency of the string (and/or instrument body) cutting down on the reverberation.[29] The wolf tone occurs because the strings below the bridge sometimes resonate at pitches close to notes on the playing part of the string. When the intended note makes the below-the-bridge string vibrate sympathetically, a dissonant "wolf note" or "wolf tone" can occur. In some cases, the wolf tone is strong enough to cause an audible "beating" sound. The wolf tone often occurs with the note G♯ on the bass.[30][31]

In orchestra, instruments tune to an A played by the oboist. Due to the three-octave gap between the oboist's tuning A and the open A string on the bass (for example, in an orchestra that tunes to 440 Hz, the oboist plays an A4 at 440 Hz and the open A1 of the bass is 55 Hz) it can be difficult to tune the bass by ear during the short period that the oboist plays the tuning note. Violinists, on the other hand, tune their A string to the same frequency as the oboist's tuning note. There is a method commonly used to tune a double bass in this context by playing the A harmonic on the D string (which is only an octave below the oboe A) and then matching the harmonics of the other strings. However, this method is not foolproof, since some basses' harmonics are not perfectly in tune with the open strings. To ensure the bass is in tune, some bassists use an electronic tuner that indicates pitch on a small display. Bassists who play in styles that use a bass amp, such as blues, rockabilly, or jazz, may use a stompbox-format electronic tuner, which mutes the bass pickup during tuning.

A double bass stand is used to hold the instrument in place and raise it a few inches off the ground. A wide variety of stands are available, and there is no one common design.

Classical repertoire

[edit]Solo works for double bass

[edit]1700s

[edit]The double bass as a solo instrument enjoyed a period of popularity during the 18th century and many of the most popular composers from that era wrote pieces for the double bass. The double bass, then often referred to as the Violone, used different tunings from region to region. The "Viennese tuning" (A1–D2–F♯2–A2) was popular, and in some cases a fifth string or even sixth string was added (F1–A1–D2–F♯2–A2).[32] The popularity of the instrument is documented in Leopold Mozart's second edition of his Violinschule, where he writes "One can bring forth difficult passages easier with the five-string violone, and I heard unusually beautiful performances of concertos, trios, solos, etc."

The earliest known concerto for double bass was written by Joseph Haydn c.1763, and is presumed lost in a fire at the Eisenstadt library. The earliest known existing concertos are by Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf, who composed two concertos for the double bass and a Sinfonia Concertante for viola and double bass. Other composers that have written concertos from this period include Johann Baptist Wanhal, Franz Anton Hoffmeister (3 concertos), Leopold Kozeluch, Anton Zimmermann, Antonio Capuzzi, Wenzel Pichl (2 concertos), and Johannes Matthias Sperger (18 concertos). While many of these names were leading figures to the music public of their time, they are generally unknown by contemporary audiences. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's concert aria, Per questa bella mano, K.612 for bass, double bass obbligato, and orchestra contains impressive writing for solo double bass of that period. It remains popular among both singers and double bassists today.

The double bass eventually evolved to fit the needs of orchestras that required lower notes and a louder sound. The leading double bassists from the mid-to-late 18th century, such as Josef Kämpfer, Friedrich Pischelberger, and Johannes Mathias Sperger employed the "Viennese" tuning. Bassist Johann Hindle (1792–1862), who composed a concerto for the double bass, pioneered tuning the bass in fourths, which marked a turning point for the double bass and its role in solo works. Bassist Domenico Dragonetti was a prominent musical figure and an acquaintance of Haydn and Ludwig van Beethoven. His playing was known all the way from his homeland Italy to the Tsardom of Russia and he found a prominent place performing in concerts with the Philharmonic Society of London. Beethoven's friendship with Dragonetti may have inspired him to write difficult, separate parts for the double bass in his symphonies, such as the impressive passages in the third movement of the Fifth Symphony, the second movement of the Seventh Symphony, and last movement of the Ninth Symphony. These parts do not double the cello part.

Dragonetti wrote ten concertos for the double bass and many solo works for bass and piano. During Rossini's stay in London in the summer of 1824, he composed his popular Duetto for cello and double bass for Dragonetti and the cellist David Salomons. Dragonetti frequently played on a three string double bass tuned G–D–A from top to bottom. The use of only the top three strings was popular for bass soloists and principal bassists in orchestras in the 19th century, because it reduced the pressure on the wooden top of the bass, which was thought to create a more resonant sound. As well, the low E-strings used during the 19th century were thick cords made of gut, which were difficult to tune and play.

1800s

[edit]

In the 19th century, the opera conductor, composer, and bassist Giovanni Bottesini was considered the "Paganini of the double bass" of his time, a reference to the violin virtuoso and composer. Bottesini's bass concertos were written in the popular Italian opera style of the 19th century, which exploit the double bass in a way that was not seen beforehand. They require virtuosic runs and great leaps to the highest registers of the instrument, even into the realm of natural and artificial harmonics. Many 19th century and early 20th century bassists considered these compositions unplayable, but in the 2000s, they are frequently performed. During the same time, a prominent school of bass players in the Czech region arose, which included Franz Simandl, Theodore Albin Findeisen, Josef Hrabe, Ludwig Manoly, and Adolf Mišek. Simandl and Hrabe were also pedagogues whose method books and studies remain in use in the 2000s.

1900s–present

[edit]The leading figure of the double bass in the early 20th century was Serge Koussevitzky, best known as conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, who popularized the double bass in modern times as a solo instrument. Because of improvements to the double bass with steel strings and better set-ups, the bass is now played at a more advanced level than ever before and more and more composers have written works for the double bass. In the mid-century and in the following decades, many new concerti were written for the double bass, including Nikos Skalkottas's Concerto (1942), Eduard Tubin's Concerto (1948), Lars-Erik Larsson's Concertino (1957), Gunther Schuller's Concerto (1962), Hans Werner Henze's Concerto (1966) and Frank Proto's Concerto No. 1 (1968).

The Solo For Contrabass is one of the parts of John Cage's Concert For Piano And Orchestra and can be played as a solo, or with any of the other parts both orchestral and/or piano. Similarly, his solo contrabass parts for the orchestral work Atlas Eclipticalis can also be performed as solos. Cage's indeterminate works such as Variations I, Variations II, Fontana Mix, Cartridge Music et al. can be arranged for a solo contrabassist. His work 26.1.1499 for a String Player is often realized by a solo contrabass player, although it can also be played by a violinist, violist, or cellist.

From the 1960s through the end of the century Gary Karr was the leading proponent of the double bass as a solo instrument and was active in commissioning or having hundreds of new works and concerti written especially for him. Karr was given Koussevitzky's famous solo double bass by Olga Koussevitsky and played it in concerts around the world for 40 years before, in turn, giving the instrument to the International Society of Bassists for talented soloists to use in concert. Another important performer in this period, Bertram Turetzky, commissioned and premiered more than 300 double bass works.

In the 1970s, 1980 and 1990s, new concerti included Nino Rota's Divertimento for Double Bass and Orchestra (1973), Alan Ridout's concerto for double bass and strings (1974), Jean Françaix's Concerto (1975), Frank Proto's Concerto No. 2, Einojuhani Rautavaara's Angel of Dusk (1980), Gian Carlo Menotti's Concerto (1983), Christopher Rouse's Concerto (1985), Henry Brant's Ghost Nets (1988) and Frank Proto's "Carmen Fantasy for Double Bass and Orchestra" (1991) and "Four Scenes after Picasso" Concerto No. 3 (1997). Peter Maxwell Davies' lyrical Strathclyde Concerto No. 7, for double bass and orchestra, dates from 1992.

In the first decade of the 21st century, new concerti include Frank Proto's "Nine Variants on Paganini" (2002), Kalevi Aho's Concerto (2005), John Harbison's Concerto for Bass Viol (2006), André Previn's Double Concerto for violin, double bass, and orchestra (2007) and John Woolrich's To the Silver Bow, for double bass, viola and strings (2014).

Reinhold Glière wrote an Intermezzo and Tarantella for double bass and piano, Op. 9, No. 1 and No. 2 and a Praeludium and Scherzo for double bass and piano, Op. 32 No. 1 and No. 2. Paul Hindemith wrote a rhythmically challenging Double Bass Sonata in 1949. Frank Proto wrote his Sonata "1963" for Double Bass and Piano. In the Soviet Union, Mieczysław Weinberg wrote his Sonata No. 1 for double bass solo in 1971. Giacinto Scelsi wrote two double bass pieces called Nuits in 1972, and then in 1976, he wrote Maknongan, a piece for any low-voiced instrument, such as double bass, contrabassoon, or tuba. Vincent Persichetti wrote solo works—which he called "Parables"—for many instruments. He wrote Parable XVII for Double Bass, Op. 131 in 1974. Sofia Gubaidulina penned a Sonata for double bass and piano in 1975. In 1976 American minimalist composer Tom Johnson wrote "Failing – a very difficult piece for solo string bass" in which the player has to perform an extremely virtuosic solo on the bass whilst simultaneously reciting a text which says how very difficult the piece is and how unlikely he or she is to successfully complete the performance without making a mistake.

In 1977 Dutch-Hungarian composer Géza Frid wrote a set of variations on The Elephant from Saint-Saëns' Le Carnaval des Animaux for scordatura double bass and string orchestra. In 1987 Lowell Liebermann wrote his Sonata for Contrabass and Piano Op. 24. Fernando Grillo wrote the "Suite No. 1" for double bass (1983/2005). Jacob Druckman wrote a piece for solo double bass entitled Valentine. US double bass soloist and composer Bertram Turetzky (born 1933) has performed and recorded more than 300 pieces written by and for him. He writes chamber music, baroque music, classical, jazz, renaissance music, improvisational music and world music

US minimalist composer Philip Glass wrote a prelude focused on the lower register that he scored for timpani and double bass. Italian composer Sylvano Bussotti, whose composing career spans from the 1930s to the first decade of the 21st century, wrote a solo work for bass in 1983 entitled Naked Angel Face per contrabbasso. Fellow Italian composer Franco Donatoni wrote a piece called Lem for contrabbasso in the same year. In 1989, French composer Pascal Dusapin (born 1955) wrote a solo piece called In et Out for double bass. In 1996, the Sorbonne-trained Lebanese composer Karim Haddad composed Ce qui dort dans l'ombre sacrée ("He who sleeps in the sacred shadows") for Radio France's Presence Festival. Renaud Garcia-Fons (born 1962) is a French double bass player and composer, notable for drawing on jazz, folk, and Asian music for recordings of his pieces like Oriental Bass (1997).

Two significant recent works written for solo bass include, Mario Davidovsky's Synchronisms No.11 for double bass and electronic sounds and Elliott Carter's Figment III, for solo double bass. The German composer Gerhard Stäbler wrote Co-wie Kobalt (1989–90), "...a music for double bass solo and grand orchestra". Charles Wuorinen added several important works to the repertoire, Spinoff trio for double bass, violin and conga drums, and Trio for Bass Instruments double bass, tuba and bass trombone, and in 2007 Synaxis for double bass, horn, oboe and clarinet with timpani and strings. The suite "Seven Screen Shots" for double bass and piano (2005) by Ukrainian composer Alexander Shchetynsky has a solo bass part that includes many unconventional methods of playing. The German composer Claus Kühnl wrote Offene Weite / Open Expanse (1998) and Nachtschwarzes Meer, ringsum… (2005) for double bass and piano.In 1997 Joel Quarrington commissioned the American / Canadian composer Raymond Luedeke to write his "Concerto for Double Bass and Orchestra", a piece he performed with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, with the Saskatoon Symphony Orchestra, and, in a version for small orchestra, with the Nova Scotia Symphony Orchestra.[33] Composer Raymond Luedeke also composed a work for double bass, flute, and viola with narration, "The Book of Questions", with text by Pablo Neruda.[34]

In 2004 Italian double bassist and composer Stefano Scodanibbio made a double bass arrangement of Luciano Berio's 2002 solo cello work Sequenza XIV with the new title Sequenza XIVb.

Chamber music with double bass

[edit]Since there is no established instrumental ensemble that includes the double bass, its use in chamber music has not been as exhaustive as the literature for ensembles such as the string quartet or piano trio. Despite this, there is a substantial number of chamber works that incorporate the double bass in both small and large ensembles.

There is a small body of works written for piano quintet with the instrumentation of piano, violin, viola, cello, and double bass. The most famous is Franz Schubert's Piano Quintet in A major, known as "The Trout Quintet" for its set of variations in the fourth movement of Schubert's Die Forelle. Other works for this instrumentation written from roughly the same period include those by Johann Nepomuk Hummel, George Onslow, Jan Ladislav Dussek, Louise Farrenc, Ferdinand Ries, Franz Limmer, Johann Baptist Cramer, and Hermann Goetz. Later composers who wrote chamber works for this quintet include Ralph Vaughan Williams, Colin Matthews, Jon Deak, Frank Proto, and John Woolrich. Slightly larger sextets written for piano, string quartet, and double bass have been written by Felix Mendelssohn, Mikhail Glinka, Richard Wernick, and Charles Ives.

In the genre of string quintets, there are a few works for string quartet with double bass. Antonín Dvořák's String Quintet in G major, Op.77 and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's Serenade in G major, K.525 ("Eine kleine Nachtmusik") are the most popular pieces in this repertoire, along with works by Miguel del Águila (Nostalgica for string quartet and bass), Darius Milhaud, Luigi Boccherini (3 quintets), Harold Shapero, and Paul Hindemith. Another example is Alistair Hinton's String Quintet (1969–77), which also includes a major part for solo soprano; at almost 170 minutes in duration, it is almost certainly the largest such work in the repertoire.

Slightly smaller string works with the double bass include six string sonatas by Gioachino Rossini, for two violins, cello, and double bass written at the age of twelve over the course of three days in 1804. These remain his most famous instrumental works and have also been adapted for wind quartet. Rossini and Dragonetti composed duos for cello and double bass, as did Johannes Matthias Sperger, a major soloist on the "Viennese" tuning instrument of the 18th century. Franz Anton Hoffmeister wrote four String Quartets for Solo Double Bass, Violin, Viola, and Cello in D Major. Frank Proto has written a Trio for Violin, Viola and Double Bass (1974), 2 Duos for Violin and Double Bass (1967 and 2005), and The Games of October for Oboe/English Horn and Double Bass (1991).

Larger works that incorporate the double bass include Beethoven's Septet in E♭ major, Op. 20, one of his most famous pieces during his lifetime, which consists of clarinet, horn, bassoon, violin, viola, cello, and bass. When the clarinetist Ferdinand Troyer commissioned a work from Franz Schubert for similar forces, he added one more violin for his Octet in F major, D.803. Paul Hindemith used the same instrumentation as Schubert for his own Octet. In the realm of even larger works, Mozart included the double bass in addition to 12 wind instruments for his "Gran Partita" Serenade, K.361 and Martinů used the double bass in his nonet for wind quintet, violin, viola, cello and double bass.

Other examples of chamber works that use the double bass in mixed ensembles include Sergei Prokofiev's Quintet in G minor, Op. 39 for oboe, clarinet, violin, viola, and double bass; Miguel del Águila's Malambo for bass flute and piano and for string quartet, bass and bassoon; Erwin Schulhoff's Concertino for flute/piccolo, viola, and double bass; Frank Proto's Afro-American Fragments for bass clarinet, cello, double bass and narrator and Sextet for clarinet and strings; Fred Lerdahl's Waltzes for violin, viola, cello, and double bass; Mohammed Fairouz's Litany for double bass and wind quartet; Mario Davidovsky's Festino for guitar, viola, cello, and double bass; and Iannis Xenakis's Morsima-Amorsima for piano, violin, cello, and double bass. There are also new music ensembles that utilize the double bass such as Time for Three and PROJECT Trio.

Orchestral passages and solos

[edit]

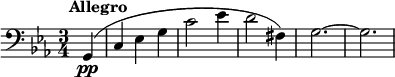

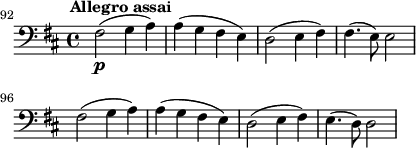

In the baroque and classical periods, composers typically had the double bass double the cello part in orchestral passages. A notable exception is Haydn, who composed solo passages for the double bass in his Symphonies No. 6 Le Matin, No. 7 Le midi, No. 8 Le Soir, No. 31 Horn Signal, and No. 45 Farewell—but who otherwise grouped bass and cello parts together. Beethoven paved the way for separate double bass parts, which became more common in the romantic era. The scherzo and trio from Beethoven's Fifth Symphony are famous orchestral excerpts, as is the recitative at the beginning of the fourth movement of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. In many nineteenth century symphonies and concertos, the typical impact of separate bass and cello parts was that bass parts became simpler and cello parts got the melodic lines and rapid passage work.[citation needed]

A double bass section of a modern orchestra typically uses eight double bassists, usually in unison. Smaller orchestras may have four double basses, and in exceptional cases, bass sections may have as many as ten members. If some double bassists have low C extensions, and some have regular (low E) basses, those with the low C extensions may play some passages an octave below the regular double basses. Also, some composers write divided (divisi) parts for the basses, where upper and lower parts in the music are often assigned to "outside" (nearer the audience) and "inside" players. Composers writing divisi parts for bass often write perfect intervals, such as octaves and fifths, but in some cases use thirds and sixths.

of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony.

Where a composition calls for a solo bass part, the principal bass invariably plays that part. The section leader (or principal) also determines the bowings, often based on bowings set out by the concertmaster. In some cases, the principal bass may use a slightly different bowing than the concertmaster, to accommodate the requirements of playing bass. The principal bass also leads entrances for the bass section, typically by lifting the bow or plucking hand before the entrance or indicating the entrance with the head, to ensure the section starts together. Major professional orchestras typically have an assistant principal bass player, who plays solos and leads the bass section if the principal is absent.

While orchestral bass solos are somewhat rare, there are some notable examples. Johannes Brahms, whose father was a double bass player, wrote many difficult and prominent parts for the double bass in his symphonies. Richard Strauss assigned the double bass daring parts, and his symphonic poems and operas stretch the instrument to its limits. "The Elephant" from Camille Saint-Saëns' The Carnival of the Animals is a satirical portrait of the double bass, and American virtuoso Gary Karr made his televised debut playing "The Swan" (originally written for the cello) with the New York Philharmonic conducted by Leonard Bernstein. The third movement of Gustav Mahler's first symphony features a solo for the double bass that quotes the children's song Frere Jacques, transposed into a minor key. Sergei Prokofiev's Lieutenant Kijé Suite features a difficult and very high double bass solo in the "Romance" movement. Benjamin Britten's The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra contains a prominent passage for the double bass section.

Double bass ensembles

[edit]Ensembles made up entirely of double basses, though relatively rare, also exist, and several composers have written or arranged for such ensembles. Compositions for four double basses exist by Gunther Schuller, Jacob Druckman, James Tenney, Claus Kühnl, Robert Ceely, Jan Alm, Bernhard Alt, Norman Ludwin, Frank Proto, Joseph Lauber, Erich Hartmann, Colin Brumby, Miloslav Gajdos and Theodore Albin Findeisen. David A. Jaffe's "Who's on First?",[35] commissioned by the Russian National Orchestra is scored for five double basses. Bertold Hummel wrote a Sinfonia piccola[36] for eight double basses. Larger ensemble works include Galina Ustvolskaya's Composition No. 2, "Dies Irae" (1973), for eight double basses, piano, and wooden cube, José Serebrier's "George and Muriel" (1986), for solo bass, double bass ensemble, and chorus, and Gerhard Samuel's What of my music! (1979), for soprano, percussion, and 30 double basses.

Double bass ensembles include L'Orchestre de Contrebasses (6 members),[37] Bass Instinct (6 members),[38] Bassiona Amorosa (6 members),[39] the Chicago Bass Ensemble (4+ members),[40] Ludus Gravis founded by Daniele Roccato and Stefano Scodanibbio, The Bass Gang (4 members),[41] the London Double Bass Ensemble (6 members) founded by members of the Philharmonia Orchestra of London who produced the LP[42] Music Interludes by London Double Bass Ensemble on Bruton Music records, Brno Double Bass Orchestra (14 members) founded by the double bass professor at Janáček Academy of Music and Performing Arts and principal double bass player at Brno Philharmonic Orchestra – Miloslav Jelinek, and the ensembles of Ball State University (12 members), Shenandoah University, and the Hartt School of Music. The Amarillo Bass Base of Amarillo, Texas once featured 52 double bassists,[43][44] and The London Double Bass Sound, who have released a CD on Cala Records, have 10 players.[45]

In addition, the double bass sections of some orchestras perform as an ensemble, such as the Chicago Symphony Orchestra's Lower Wacker Consort.[46] There is an increasing number of published compositions and arrangements for double bass ensembles, and the International Society of Bassists regularly features double bass ensembles (both smaller ensembles as well as very large "mass bass" ensembles) at its conferences, and sponsors the biennial David Walter Composition Competition, which includes a division for double bass ensemble works.

Use in jazz

[edit]Beginning around 1890, the early New Orleans jazz ensemble (which played a mixture of marches, ragtime, and Dixieland) was initially a marching band with a tuba or sousaphone (or occasionally bass saxophone) supplying the bass line. As the music moved into bars and brothels, the upright bass gradually replaced these wind instruments around the 1920s.[47] Many early bassists doubled on both the brass bass (tuba) and string bass, as the instruments were then often referred to. Bassists played improvised "walking" bass lines—scale- and arpeggio-based lines that outlined the chord progression.

Because an unamplified upright bass is generally the quietest instrument in a jazz band, many players of the 1920s and 1930s used the slap style, slapping and pulling the strings to produce a rhythmic "slap" sound against the fingerboard. The slap style cuts through the sound of a band better than simply plucking the strings, and made the bass more easily heard on early sound recordings, as the recording equipment of that time did not favor low frequencies.[48] For more about the slap style, see Modern playing styles, below.

Jazz bass players are expected to improvise an accompaniment line or solo for a given chord progression. They are also expected to know the rhythmic patterns that are appropriate for different styles (e.g., Afro-Cuban). Bassists playing in a big band must also be able to read written-out bass lines, as some arrangements have written bass parts.

Many upright bass players have contributed to the evolution of jazz. Examples include swing era players such as Jimmy Blanton, who played with Duke Ellington, and Oscar Pettiford, who pioneered the instrument's use in bebop. Paul Chambers (who worked with Miles Davis on the famous Kind of Blue album) achieved renown for being one of the first jazz bassists to play bebop solos with the bow. Terry Plumeri furthered the development of arco (bowed) solos, achieving horn-like technical freedom and a clear, vocal bowed tone, while Charlie Haden, best known for his work with Ornette Coleman, defined the role of the bass in Free Jazz.

A number of other bassists, such as Ray Brown, Slam Stewart and Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen, were central to the history of jazz. Stewart, who was popular with the beboppers, played his solos with a bow combined with octave humming. Notably, Charles Mingus was a highly regarded composer as well as a bassist noted for his technical virtuosity and powerful sound.[49] Scott LaFaro influenced a generation of musicians by liberating the bass from contrapuntal "walking" behind soloists instead favoring interactive, conversational melodies.[50] Since the commercial availability of bass amplifiers in the 1950s, jazz bassists have used amplification to augment the natural volume of the instrument.

While the electric bass guitar was used intermittently in jazz as early as 1951, beginning in the 1970s bassist Bob Cranshaw, playing with saxophonist Sonny Rollins, and fusion pioneers Jaco Pastorius and Stanley Clarke began to commonly substitute the bass guitar for the upright bass. Apart from the jazz styles of jazz fusion and Latin-influenced jazz however, the upright bass is still the dominant bass instrument in jazz. The sound and tone of the plucked upright bass is distinct from that of the fretted bass guitar. The upright bass produces a different sound than the bass guitar, because its strings are not stopped by metal frets, instead having a continuous tonal range on the uninterrupted fingerboard. As well, bass guitars usually have a solid wood body, which means that their sound is produced by electronic amplification of the vibration of the strings, instead of the upright bass's acoustic reverberation.

Demonstrative examples of the sound of a solo double bass and its technical use in jazz can be heard on the solo recordings Emerald Tears (1978) by Dave Holland or Emergence (1986) by Miroslav Vitouš. Holland also recorded an album with the representative title Music from Two Basses (1971) on which he plays with Barre Phillips while he sometimes switches to cello.

Use in bluegrass and country

[edit]The string bass is the most commonly used bass instrument in bluegrass music and is almost always plucked, though some modern bluegrass bassists have also used a bow. The bluegrass bassist is part of the rhythm section, and is responsible for keeping a steady beat, whether fast, slow, in 4

4, 2

4 or 3

4 time. The bass also maintains the chord progression and harmony. The Engelhardt-Link (formerly Kay) brands of plywood laminate basses have long been popular choices for bluegrass bassists. Most bluegrass bassists use the 3⁄4 size bass, but the full-size and 5⁄8 size basses are also used.

Early pre-bluegrass traditional music was often accompanied by the cello. The cellist Natalie Haas points out that in the US, you can find "...old photographs, and even old recordings, of American string bands with cello". However, "The cello dropped out of sight in folk music, and became associated with the orchestra."[51] The cello did not reappear in bluegrass until the 1990s and first decade of the 21st century. Some contemporary bluegrass bands favor the electric bass, because it is easier to transport than the large and somewhat fragile upright bass. However, the bass guitar has a different musical sound. Many musicians feel the slower attack and percussive, woody tone of the upright bass gives it a more "earthy" or "natural" sound than an electric bass, particularly when gut strings are used.

Common rhythms in bluegrass bass playing involve (with some exceptions) plucking on beats 1 and 3 in 4

4 time; beats 1 and 2 in 2

4 time, and on the downbeat in 3