Cologne Cathedral

| Cologne Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| The Cathedral of St. Peter | |

| |

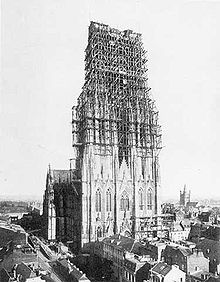

Cathedral façade | |

| |

| 50°56′29″N 06°57′30″E / 50.94139°N 6.95833°E | |

| Location | Cologne |

| Country | Germany |

| Denomination | Catholic Church |

| Website | koelner-dom.de https://www.koelner-dom.de/en |

| History | |

| Status | Cathedral |

| Dedication | Saint Peter |

| Consecrated | 15 October 1880 |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Style | Gothic |

| Years built |

|

| Specifications | |

| Length | 144.5 m (474 ft)[1] |

| Width | 86.25 m (283.0 ft)[1] |

| Number of spires | 2 |

| Spire height | 157 m (515 ft)[1] |

| Bells | 11 |

| Administration | |

| Province | Cologne |

| Archdiocese | Cologne |

| Clergy | |

| Archbishop | Rainer Woelki |

| Provost | Guido Assmann[2] |

| Vice-provost | Robert Kleine |

| Vicar(s) | Jörg Stockem |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | Eberhard Metternich |

| Organist(s) | Winfried Bönig[3] |

| Organ scholar | Ulrich Brüggemann |

Building details | |

| Record height | |

| Tallest in the world from 1880 to 1890[I] | |

| Preceded by | Rouen Cathedral |

| Surpassed by | Ulm Minster |

| Height | |

| Antenna spire | 157.4 m (516 ft) |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iv |

| Reference | 292 |

| Inscription | 1996 (20th Session) |

| Endangered | 2004–06 |

Cologne Cathedral (German: Kölner Dom, pronounced [ˌkœlnɐ ˈdoːm] ⓘ, officially Hohe Domkirche Sankt Petrus, English: Cathedral Church of Saint Peter) is a cathedral in Cologne, North Rhine-Westphalia belonging to the Catholic Church. It is the seat of the Archbishop of Cologne and of the administration of the Archdiocese of Cologne. It is a renowned monument of German Catholicism and Gothic architecture and was declared a World Heritage Site in 1996.[4][5] It is Germany's most visited landmark, attracting an average of 6 million people a year.[6] At 157 m (515 ft), the cathedral is the tallest twin-spired church in the world, the second tallest church in Europe after Ulm Minster, and the third tallest church of any kind in the world.[7]

Construction of Cologne Cathedral began in 1248 but was halted in the years around 1560,[8] unfinished. Attempts to complete the construction began around 1814 but the project was not properly funded until the 1840s. The edifice was completed to its original medieval plan in 1880.[9] The towers for its two huge spires give the cathedral the largest façade of any church in the world.

Cologne's medieval builders had planned a grand structure to house the reliquary of the Three Kings and fit for its role as a place of worship for the Holy Roman Emperor. Despite having been left incomplete during the medieval period, Cologne Cathedral eventually became unified as "a masterpiece of exceptional intrinsic value" and "a powerful testimony to the strength and persistence of Christian belief in medieval and modern Europe".[5] In Cologne, only the telecommunications tower is higher than the cathedral.[4]

Predecessor buildings

[edit]Merovingian episcopal church

[edit]Maternus of Cologne was the first bishop of Cologne in around 313.[10] However, Cologne's Christian community, still small at this time, did not gather in a church, but in a residential building, which is thought to have been located on the cathedral hill below today's choir.[11] After the collapse of Roman rule on the Rhine, the Merovingian petty kings residing in Cologne built an episcopal church on this site in the 6th century, which was eventually around 40 to 50 meters long and equipped with an ambon. This building, which was probably built by King Theudebert I, served as a burial place for the royal family; among others, the king's wife Wisigard was buried here around 537. However, the excavation finds under the cathedral choir do not allow a complete reconstruction of the buildings from the Merovingian period.[12]

Baptistry

[edit]

Already in late antiquity, there was a baptistery to the east of the cathedral choir, where the early Christians, following the rite of the time, stepped into knee-deep water and were completely doused. It is assumed that the baptismal font (piscina), which dates back to the 5th century, was originally located in the garden of the Roman house that served as a Christian meeting place.[13] Later, the baptistry built above the pool was presumably combined with the cathedral church to form a single building complex, although there is no archaeological evidence of this today.[14] When Hildebold Cathedral was built and equipped with a baptismal font due to the changed rite, only the baptismal piscina remained from the baptistery. [15] Today, this piscina, which is accessible in the base of the cathedral, is considered the oldest evidence of Christian worship in Cologne.[16]

Hildebold Cathedral

[edit]

In Carolingian times, the Old Cathedral was built on Cologne Cathedral Hill and consecrated in 870.[17] The cathedral is now known as Hildebold Cathedral after Bishop Hildebold, who was a close advisor to Charlemagne and died in 818. However, it is unclear how much the bishop contributed to the building. He probably started the new construction, which Charlemagne also generously supported.[18] The bishop's residence was originally located next to the cathedral.

With a length of around 95 meters, Hildebold Cathedral was one of the largest Carolingian churches ever built and became the architectural rolemodel for numerous churches in the early Holy Roman Empire. It was built in the Carolingian tradition as a basilica with two choirs, with the east choir dedicated to Mary, mother of Jesus and the more important choir in the west to the memory of Saint Peter. Through its patronage, but also in its architecture, Hildebold Cathedral made reference to Old St. Peter's Basilica in Rome[19] and was regarded as the St. Peter's Basilica of the North. This was intended to underline Cologne's claim to be a holy city and faithful daughter of the Roman Church.[20] The so-called reliquary-staff of Saint Peter and the chains of Saint Peter were among the church's most important relics.[21] The Hillinus Codex from the 11th century shows Hildebold Cathedral in an unusually realistic depiction for the time. [22] Today, the foundation walls of the Carolingian basilica have been revealed by the cathedral excavations.[23]

On 23 July 1164, the Archbishop of Cologne and Imperial Archchancellor Rainald of Dassel brought the bones of the Three Wise Men from Milan to Cologne, which was perceived as a "propaganda success".[24] The relics had been left to the archbishop by Emperor Frederick Barbarossa from his spoils of war. They had been considered worthy of veneration at least since their transfer. Whether Rainald von Dassel himself or the Milanese patricians should be regarded as the "inventors" of the relics is disputed in academic literature.[25] In any case, between 1190 and 1225, the Shrine of the Three Kings was made for the highly respected saints in Cologne, which is considered one of the most sophisticated goldsmith's works of the Middle Ages; the shrine was placed in the center of the Old Cathedral.[26] Cologne thus became an internationally renowned place of pilgrimage in Europe. [27] To oversee the pilgrim crowds, an office of custos regum ("guardian of the kings") was established after 1162.[28] However, the only narrow side portal of the cathedral was not very suitable for the crowds of pilgrims, as it had to be used as an entrance and an exit at the same time.[29]

With the construction of the Gothic cathedral in 1248, the Old Cathedral was to be demolished step by step. However, careless demolition work and fire destroyed not only the east choir, but almost the entire cathedral; the Shrine of the Three Kings was saved from the fire. The western parts of Hildebold Cathedral were provisionally rebuilt and were only taken down after 1322, when the Gothic choir was completed and construction of the Gothic nave began. [30]

Building history of the Gothic cathedral

[edit]Medieval beginning

[edit]The foundation stone was laid on Saturday, 15 August 1248, by Archbishop Konrad von Hochstaden.[31] The eastern arm was completed under the direction of Master Gerhard, was consecrated in 1322 and sealed off by a temporary wall so it could be used as the work continued. Eighty-four misericords in the choir date from this building phase.[citation needed]. This work ceased in 1473, leaving the south tower complete to the belfry level and crowned with a huge crane that remained in place as a landmark of the Cologne skyline for 400 years.[32][page needed] Some work proceeded intermittently on the structure of the nave between the west front and the eastern arm, but during the 16th century this also stopped.[33][page needed]

-

The unfinished cathedral in 1820, engraved by Henry Winkles. The huge crane on the tower of the cathedral is visible in the picture.

-

The unfinished cathedral in 1855. The medieval crane was still in place, while constructions for the nave had been resumed earlier in 1814.

-

The unfinished cathedral in 1856. The east end had been finished and roofed, while other parts of the building are in various stages of construction.

19th-century completion

[edit]

With the 19th-century Romantic enthusiasm for the Middle Ages, and spurred by the discovery of the original plan for the façade, the Protestant Prussian Court working with the church, committed to complete the cathedral. It was achieved by civic effort; the Central-Dombauverein, founded in 1842, raised two-thirds of the enormous costs, while the Prussian state supplied the remaining third.[citation needed] The state saw this as a way to improve its relations with the large number of Catholic subjects it had gained in 1815, but especially after 1871, it was regarded as a project to symbolize German nationhood.[34]

Work resumed in 1842 to the original design of the surviving medieval plans and drawings, but using more modern construction techniques, including iron roof girders. The nave was completed and the towers were added. The bells were installed in the 1870s. The largest bell is St. Petersglocke.[citation needed]

The completion of Germany's largest cathedral was celebrated as a national event on 15 October 1880, 632 years after construction had begun.[35] The celebration was attended by Emperor Wilhelm I. With a height of 157.38 m (516.3 ft), it was the tallest building in the world for four years until the completion of the Washington Monument.[36]

World War II and post-war history

[edit]The twin spires of the cathedral were an easily recognizable navigational landmark for Allied aircraft bombing during World War II.[37] The cathedral suffered fourteen hits by aerial bombs during the war. Badly damaged, it nevertheless remained standing in an otherwise completely flattened city.

On 6 March 1945, an area west of the cathedral (Marzellenstrasse/Trankgasse) was the site of intense combat between American tanks of the 3rd Armored Division and a Panther Ausf. A of Panzer brigade 106 Feldherrnhalle. A nearby Panther, a German medium tank, was sitting by a pile of rubble near a train station right by the twin spires of the Cologne Cathedral. The Panther successfully knocked out two Sherman tanks, killing three men, before it was destroyed by a T26E3 Pershing, nicknamed Eagle 7, minutes later. Film footage of that battle survives.[38]

Repairs of the war damage were completed in 1956. A repair to part of the northwest tower, carried out in 1944 using poor-quality brick taken from a nearby ruined building, remained visible as a reminder of the war until 2005, when it was restored to its original appearance.

To investigate whether the bombings had damaged the foundations of the Dom, archaeological excavations began in 1946 under the leadership of Otto Doppelfeld and were concluded in 1997. One of the most meaningful excavations of churches, they revealed previously unknown details of earlier buildings on the site.[39]

Repair and maintenance work is constantly being carried out in the building, which is rarely free of scaffolding, as wind, rain, and pollution slowly eat away at the stones. The Dombauhütte, established to build the cathedral and keep it in repair, employs skilled stonemasons for the purpose. Half the costs of repair and maintenance are still borne by the Dombauverein.[citation needed]

-

The west front of the completed cathedral in 1911

-

US soldier and destroyed Panther tank, 4 April 1945

21st century

[edit]On 18 August 2005, Pope Benedict XVI visited the cathedral during his apostolic visit to Germany, as part of World Youth Day 2005 festivities. An estimated one million pilgrims visited the cathedral during this time. Also as part of the events of World Youth Day, Cologne Cathedral hosted a televised gala performance of Beethoven's Missa Solemnis, performed by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and the London Philharmonic Choir conducted by Gilbert Levine.[40]

On 25 August 2007, the cathedral received a new stained glass window in the south transept. The 113 m2 (1,220 sq ft) glass work was created by the German artist Gerhard Richter with the €400,000 cost paid by donations. It is composed of 11,500 identically sized pieces of coloured glass resembling pixels, randomly arranged by computer, which create a colourful "carpet". Since the loss of the original window in World War II, the space had been temporarily filled with plain glass.[41] The then archbishop of the cathedral, Cardinal Joachim Meisner, who had preferred a figurative depiction of 20th-century Catholic martyrs for the window, did not attend the unveiling.[42] Holder of the office since 2014 is Cardinal Rainer Maria Woelki. On 5 January 2015, the cathedral remained dark as floodlights were switched off to protest a demonstration by PEGIDA.[43]

World Heritage Site

[edit]

In 1996, the cathedral was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List of culturally important sites.[9] In 2004, it was placed on the "World Heritage in Danger" list, as the only Western site in danger, due to plans to construct several high-rise buildings nearby, which would have visually impacted the site.[44][45] The cathedral was removed from the "in danger" list in 2006, following the authorities' decision to limit the heights of buildings constructed near and around the cathedral.[46]

As a World Heritage Site and host to the Shrine of the Three Kings, Cologne Cathedral is a major attraction for tourists and pilgrims, and is one of the oldest and most important pilgrimage sites of Northern Europe.[47] Visitors can climb 533 stone steps of the spiral staircase to a viewing platform about 100 m (330 ft) above the ground.[48] The platform gives a scenic view over the Rhine.

Ongoing renovation

[edit]

The cathedral is a medieval building that was built very solidly from a structural point of view. At the same time, however, the stone structure requires continuous maintenance and renovation.[49] The cathedral's master builder Barbara Schock-Werner said: "Cologne Cathedral without scaffolding is not a pipe dream, but a nightmare. It would mean that we would no longer be able to afford the cathedral."[50]

In fact, the completed cathedral was only visible without scaffolding for a few years. After the official completion of the cathedral in 1880, finishing work continued for around 20 years. Shortly before his death in 1902, master builder Richard Voigtel publicly stated that the cathedral had finally been completed. However, after the wings of an angel figure fell from the façade in 1906, the cathedral master builders resumed the renovation work.[51]

The cathedral is built from different types of rock, which weather to varying degrees due to their characteristics.[52] The filigree buttresses and arches are exposed to the weather from all sides[53] and are attacked by water, the sulphur content of the air and bird droppings.[54] Especially from the 1960s onwards, acid rain severely affected the stones and turned them increasingly black. It was only from the 1990s onwards that air pollution control measures reduced the level of pollution.[55]

The Schlaitdorf sandstone, which was used from 1842 onwards for the transept façades and the upper parts of the nave and transept, shows the most intensive weathering. It is therefore constantly being renewed and until the 1980s was preferably replaced with Londorf basalt lava, which is considered to be very weather-resistant, but is not sandy beige, but grey in color.[56] Since the 1990s, however, the cathedral master builders have endeavored to carry out the restoration with stones that come as close as possible to the original sandstone.[57] The cathedral works (Dombauhütte) has already tested numerous means of preserving the stones. A convincing method has not yet been found.[58] In addition, the iron anchors and dowels that hold the many parts of the architectural decoration are also beginning to rust. They are threatening to crack the stones and need to be replaced with steel parts. "It is therefore foreseeable that no one alive today will ever see the cathedral without scaffolding."[59]

Regular renovation work is required due to sporadic earthquake damage. For example, during the 1992 Roermond earthquake, the 400 kg finial on the eastern pinnacle of the southern transept gable broke off, smashed through the roof and damaged the roof truss. Four other finials were loosened.[60]

From May to November 2021, a remote-controlled drone took 200,000 high-resolution photos of all parts of the façade from a distance of five to seven meters and assembled them into a digital 3D model of the cathedral, which offers a very accurate representation with 25 billion polygons. This makes it possible to precisely document the current condition and the need for conservation and restoration, even in remote areas. The 3D model has a size of 50 gigabytes. The cost of creating the model was in the six-figure range.[61][62]

Architecture

[edit]The ground plan design of Cologne Cathedral was based closely on that of Amiens Cathedral, as is the style and the width to height proportion of the central nave. The plan is in the shape of a Latin Cross, as is usual with Gothic cathedrals. It has two aisles on either side, which help support one of the very highest Gothic vaults in the world, being nearly as tall as that of the Beauvais Cathedral, much of which collapsed. Externally the outward thrust of the vault is taken by flying buttresses in the French manner. The eastern end has a single ambulatory, the second aisle resolving into a chevet of seven radiating chapels.[citation needed]

Internally, the medieval choir is more varied and less mechanical in its details than the 19th-century building. It presents a French style arrangement of very tall arcade, a delicate narrow triforium gallery lit by windows and with detailed tracery merging with that of the windows above. The clerestory windows are tall and retain some old figurative glass in the lower sections. The whole is united by the tall shafts that sweep unbroken from the floor to their capitals at the spring of the vault. The vault is of plain quadripartite arrangement.

The choir retains a great many of its original fittings, including the carved stalls, despite French Revolutionary troops having desecrated the building. A large stone statue of St Christopher looks down towards the place where the earlier entrance to the cathedral was, before its completion in the late 19th century.

The nave has many 19th century stained glass windows. A set of five on the south side, called the Bayernfenster, were a gift from Ludwig I of Bavaria, and strongly represent the painterly German style of the time.

Externally, particularly from a distance, the building is dominated by its huge spires, which are entirely Germanic in character, being openwork like those of Ulm, Vienna, Strasbourg and Regensburg Cathedrals.[63]

-

An aerial view shows the cruciform plan.

-

The cathedral from the south

-

The exterior of one of the spires

-

The main entrance shows the 19th century decoration.

-

The flying buttresses and pinnacles of the Medieval east end

-

The nave looking east

-

Interior of the Medieval east end, showing the extreme height

-

This "swallows' nest" organ was built into the gallery in 1998 to celebrate the cathedral's 750 years.

Dimensions

[edit]| External length | 144.58 m (474.3 ft) |

| External width | 86.25 m (283.0 ft) |

| Width of west façade | 61.54 m (201.9 ft) |

| Width of transept façade | 39.95 m (131.1 ft) |

| Width of nave (with aisles, interior) | 45.19 m (148.3 ft) |

| Height of southern tower | 157.31 m (516.1 ft) |

| Height of northern tower | 157.38 m (516.3 ft) |

| Height of ridge turret | 109.00 m (357.61 ft) |

| Height of transept façades | 69.95 m (229.5 ft) |

| Height of roof ridge | 61.10 m (200.5 ft) |

| Inner height of nave | 43.35 m (142.2 ft) |

| Height of side aisles | 18 m (59 ft) |

| Building area | 7,914 m2 (85,185.59 sq ft) |

| Window surface area | 10,000 m2 (107,639.10 sq ft) |

| Roof surface area | 12,000 m2 (129,166.93 sq ft) |

| Gross volume without buttresses | 407,000 m3 (14,400,000 cu ft) |

Treasures

[edit]One of the treasures of the cathedral is the high altar, which was installed in 1322. It is constructed of black marble, with a solid slab 15 ft (4.6 m) long forming the top. The front and sides are overlaid with white marble niches into which are set figures, with the Coronation of the Virgin at the centre. Joan Holladay has discussed the iconography of the high altar in the cathedral.[64]

The most celebrated work of art in the cathedral is the Shrine of the Three Kings, commissioned by Philip von Heinsberg, archbishop of Cologne from 1167 to 1191 and created by Nicholas of Verdun, begun in 1190. It is traditionally believed to hold the remains of the Three Wise Men, whose relics were acquired by Frederick Barbarossa at the conquest of Milan in 1164. The shrine takes the form of a large reliquary in the shape of a basilican church, made of bronze and silver, gilded and ornamented with architectonic details, figurative sculpture, enamels and gemstones. The shrine was opened in 1864 and was found to contain bones and garments.

Near the sacristy is the Gero Crucifix,[65] a large crucifix carved in oak and with traces of paint and gilding. Believed to have been commissioned around 960 for Archbishop Gero, it is the oldest large crucifix north of the Alps and the earliest-known large free-standing Northern sculpture of the medieval period.[66][page needed]

In the Sacrament Chapel is the Mailänder Madonna ("Milan Madonna"), a high Gothic carving, depicting the Blessed Virgin and the infant Jesus. It was made in the Cologne Cathedral workshop sometime around 1290 as a replacement for the original which was lost in a fire. The altar of the patron saints of Cologne with an altarpiece by the International Gothic painter Stefan Lochner is in the Marienkapelle ("St. Mary's Chapel").

After completion in 1265, the radiating chapels were immediately taken into service as a burial place. The relics of Saint Irmgardis found a final resting place in the St. Agnes' Chapel. Her trachyte sarcophagus is considered to be created by the cathedral masons' guild around 1280.[67] Other works of art are in the Cathedral Treasury.

Embedded in the interior wall are a pair of stone tablets on which are carved the provisions formulated by Archbishop Englebert II (1262–67) under which Jews were permitted to reside in Cologne.[68]

-

The Crucifix of Bishop Gero, 10th century, the oldest known large crucifix

-

St. Christopher statue by Tilman van der Burch, c. 1470

-

Petrus- und Wurzel Jesse-Fenster, 1509

-

Anbetungs-Fenster, 1846

-

Modern stained glass window by Gerhard Richter (2007)

Church music

[edit]Cologne Cathedral has two pipe organs by Klais Orgelbau: the Transept Organ, built in 1948, and the Nave Organ, built in 1998.[69] Cathedral organists have included Josef Zimmermann, Clemens Ganz (1985–2001) and Winfried Bönig (2001).

Bells

[edit]The cathedral has eleven church bells, four of which are medieval. The first was the 3.8-tonne Dreikönigsglocke ("Bell of the Three Kings"), cast in 1418, installed in 1437, and recast in 1880. Two of the other bells, the Pretiosa (10.5 tonnes; at that time the largest bell in the Western world) and the Speciosa (5.6 tonnes) were installed in 1448 and remain in place today.

During the 19th century, as the building neared completion, there was a desire to increase the number of bells. This was facilitated by Kaiser Wilhelm I who gave French bronze cannon, captured in 1870–71, for this purpose.[70] The 22 pieces of artillery were displayed outside the cathedral on 11 May 1872. Andreas Hamm in Frankenthal used them to cast a bell of over 27,000 kilos on 19 August 1873. The tone was not harmonious and another attempt was made on 13 November 1873. The Central Cathedral Association, which had agreed to take over the costs, did not want this bell either. Another attempt took place on 3 October 1874. The colossal bell was shipped to Cologne and on 13 May 1875, installed in the cathedral. This Kaiserglocke was eventually melted in 1918 to support the German war effort. The Kaiserglocke was the largest free-swinging bell in history.

The 24-tonne St. Petersglocke ("Bell of St. Peter", "Decke Pitter" in the Kölsch language or in common parlance known as "Dicker Pitter"), was cast in 1922 and was the largest free-swinging bell in the world, until a new bell was cast in Innsbruck for the People's Salvation Cathedral in Bucharest, Romania.[71] This bell is only rung on eight major holidays such as Easter and Christmas.

On Thursday, 3 March 2022, landmark cathedrals across Europe chimed in unison "in a gesture of solidarity with Ukraine, as bystanders gathered to mourn those killed during Russia's invasion and pray for peace." The Kölner Dom was among them.[72]

| Name | No | Mass | Note | Founder | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Peter's Bell (Dicker Pitter) | 1 | 24,000 kg | C0 | Heinrich Ulrich, Apolda | 1923 |

| Pretiosa | 2 | 10,500 kg | G1 | Heinrich Brodermann & Christian Cloit, Cologne | 1448 |

| Speciosa | 3 | 5,600 kg | A1 | Johannes Hoerken de Vechel, Cologne | 1449 |

| Dreikönigsglocke (Three Kings Bell) | 4 | 3,800 kg | H0 | Hermann Große, Dresden | 1880 |

| St. Ursula's Bell (Ursulaglocke) | 5 | 2,500 kg | C1 | Joseph Beduwe, Aachen | 1862 |

| St. Joseph's Bell (Josephglocke) | 6 | 2,200 kg | D2 | Hans Augustus Mark, Eifel Foundry, Brockscheid | 1998 |

| Chapter Bell (Kapitelsglocke) | 7 | 1,400 kg | E2 | Karl I Otto, Bremen | 1911 |

| Hail Bell (Aveglocke) | 8 | 830 kg | G2 | Karl I Otto, Bremen | 1911 |

| Name | No | Weight | Note | Founder | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angelusglocke | 9 | 762 | G♯2 | Unknown | 14th century |

| Mettglocke | 10 | 280 | B2 | Antonius Cobelenz, Cologne | 1719 |

| Wandlungsglocke | 11 | 428 | E3 | Unknown | 14th century |

See also

[edit]- Gothic cathedrals and churches

- List of Gothic Cathedrals in Europe

- Architecture of cathedrals and great churches

- Gero Cross

- Gothic architecture

- Gothic Revival architecture

- List of buildings and structures

- List of highest church naves

- List of cathedrals in Germany

- List of tallest structures built before the 20th century

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Cologne Cathedral official website". Archived from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ "Monsignore Guido Assmann wird neuer Dompropst" (in German). Erzbistum Köln. 29 May 2020. Archived from the original on 3 June 2022. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ "Prof. Dr. Winfried Bönig" (in German). Kölner Dommusik. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Cologne Cathedral | Cologne Tourist Board". www.cologne-tourism.com. Archived from the original on 3 February 2024. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Cologne Cathedral – UNESCO World Heritage". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ "Der Dom in Zahlen". www.koelner-dom.de. Archived from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ "8 Tallest Cathedrals in the World". HISTRUCTURAL – SAHC. 8 November 2018. Archived from the original on 3 February 2024. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ Leonard Ennen, Der Dom in Köln von seinem Beginne bis zu seiner Vollendung: Festschrift gewidmet den Freunden und Gönnern aus Anlass der Vollendung vom Verstande des Central-Dombauvereins [The cathedral in Cologne from its begin to its completion: Festschrift dedicated to the friends and patrons on the occasion of the completion of the understanding of the Central Cathedral Building Association], 1880, p. 79

- ^ a b "Cologne Cathedral". UNESCO World Heritage. Archived from the original on 15 April 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ Werner Eck: Frühes Christentum in Köln. In: Ulrich Krings, Rainer Will (ed.): Das Baptisterium am Dom , Kölns erster Taufort. Köln 2009, pp. 11–21, here p. 12.

- ^ Georg Hauser: Schichten und Geschichte unter dem Dom, die Kölner Domgrabung, Köln 2003, p. 19.

- ^ Georg Hauser: Schichten und Geschichte unter dem Dom, die Kölner Domgrabung. Köln 2003, p. 25.

- ^ Georg Hauser: Schichten und Geschichte unter dem Dom, die Kölner Domgrabung. Köln 2003, p. 42f.

- ^ Werner Eck: Frühes Christentum in Köln. In: Ulrich Krings, Rainer Will (Ed.): Das Baptisterium am Dom, Kölns erster Taufort. Köln 2009, p. 11–21, here p. 19. Sebastian Ristow: Das Kölner Baptisterium am Dom und die frühchristlichen Tauforte nördlich der Alpen, in: Ulrich Krings, Rainer Will (Ed.): Das Baptisterium am Dom, Kölns erster Taufort, Köln 2009, p. 23–43, here p. 29f.

- ^ Sebastian Ristow: Das Kölner Baptisterium am Dom und die frühchristlichen Tauforte nördlich der Alpen. In: Ulrich Krings, Rainer Will (Ed.): Das Baptisterium am Dom, Kölns erster Taufort. Köln 2009, p. 23–43, here p. 31.

- ^ Bernd Streitberger: Was wird aus dem Baptisterium am Dom? In: Ulrich Krings, Rainer Will (Ed.): Das Baptisterium am Dom. Kölns erster Taufort. Köln 2009, p. 91–98.

- ^ Matthias Untermann: Zur Kölner Domweihe von 870; in: Rheinische Vierteljahresblätter 47 (1983); pp. 335–342

- ^ Karl Ubl: Köln im Frühmittelalter. Die Entstehung einer heiligen Stadt, Köln 2022, p. 188.

- ^ Lex Bosman: Vorbild und Zitat in der mittelalterlichen Architektur am Beispiel des Alten Domes in Köln. In: Uta-Maria Bräuer, Emanuel Klinkenberg, Jeroen Westerman: Kunst & Region, Architektur und Kunst im Mittelalter. Utrecht 2005, pp. 45–69.

- ^ Rüdiger Marco Booz: Kölner Dom, die vollkommene Kathedrale. Petersberg 2022, p. 17.

- ^ Georg Hauser: Zur Archäologie des Petrusstabes. In: Kölner Domblatt. 76, 2011, p. 197–217.

- ^ Holger Simon: Architekturdarstellungen in der ottonischen Buchmalerei, Der Alte Kölner Dom im Hillinus-Codex. In: Stefanie Lieb (Ed.): Form und Stil, Festschrift für Günther Binding zum 65. Geburtstag. Darmstadt 2001, p. 32–45.

- ^ Uwe Lobbedey: Rezension zu ‚Ulrich Back, Thomas Höltken und Dorothea Hochkirchen, Der Alte Dom zu Köln. Befunde und Funde zur vorgotischen Kathedrale‘; in: Bonner Jahrbücher 213 (2013/2014), p. 503– 509

- ^ Rüdiger Marco Booz: Kölner Dom, die vollkommene Kathedrale, Petersberg 2022, p. 26.

- ^ Rüdiger Marco Booz: Kölner Dom, die vollkommene Kathedrale, Petersberg 2022, p. 26.

- ^ Ulrich Back: Die Reliquien der Heiligen Drei Könige im Alten Dom, in: Leonie Becks, Matthias Deml, Klaus Hardering: Caspar Melchior Balthasar. 850 Jahre Verehrung der Heiligen Drei Könige im Kölner Dom, Köln 2014, p. 23–27.

- ^ Bernard Gui: Manuale de l‘Inquisiteur, hrsg. von G. Mollat und G. Drioux, Bd. 1, Paris 1926, p. 56.

- ^ Alheydis Plassmann, Martin Bock: Art. Köln – Domstift. In: Nordrheinisches Klosterbuch. Lexikon der Stifte und Klöster bis 1815. Teil 3: Köln. Franz Schmitt, Siegburg 2022, p. 157–198, here p. 160.

- ^ Clemens Kosch: Kölns Romanische Kirchen: Architektur und Liturgie im Hochmittelalter. Regensburg 2005, p. 14f.

- ^ Rüdiger Marco Booz: Kölner Dom, die vollkommene Kathedrale, Petersberg 2022, p. 58, 87.

- ^ "The Cologne Cathedral". Cologne.de. Archived from the original on 1 May 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ Wim Swaan

- ^ Wim Swaan gives the latest date as 1560, but a date of 1520 is considered more probable by other scholars.

- ^ Gilley, Sheridan; Stanley, Brian (2006). The Cambridge History of Christianity. Vol. 8, World Christianities c. 1815–c. 1914. Cambridge University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-521-81456-0.

- ^ Godwin, George, ed. (1881). The Builder. [s.n.] p. 419. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ Lewis, Robert (13 September 2017). "Cologne Cathedral". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 16 August 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ "In the Ruins of Cologne". The National WWII Museum | New Orleans. 5 March 2020. Archived from the original on 7 March 2024. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ Christopher Miskimon (November 2019). "Clash of Heavy Tanks at Cologne". Warfare History Network. Archived from the original on 15 November 2024. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ Klaus Gereon Beuckers: Der Kölner Dom, Darmstadt 2004, S. 113.

- ^ "Apostolic Journey to Cologne: Visit to the Cathedral of Cologne". 18 August 2005. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ "Gerhard Richter digitalisiert Kölner Dom" [Gerhard Richter digitizes Cologne Cathedral]. Der Spiegel (in German). Deutsche Presse-Agentur. 25 August 2007. Archived from the original on 5 April 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ Fortini, Amanda (9 December 2007). "Pixelated Stained Glass". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 13 June 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2008.

- ^ "Germany Pegida protests: Rallies over 'Islamisation'". BBC News. 6 January 2015. Archived from the original on 6 January 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

In Cologne, the authorities switched off the lights of the city's cathedral as a way of warning Pegida supporters they were supporting 'extremists'. 'We don't think of it as a protest, but we would like to make the many conservative Christians [who support Pegida] think about what they are doing,' the dean of the cathedral, Norbert Feldhoff, told the BBC.

- ^ "World Heritage Committee sounds the alarm for Cologne Cathedral". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "Cologne Cathedral on UNESCO Danger List". Deutsche Welle. 6 July 2004. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "UNESCO Removes Cologne Cathedral From Endangered List". Deutsche Welle. 11 July 2006. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "Cologne Cathedral". The Complete Pilgrim – Religious Travel Sites. 1 June 2014. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "Cathedral South Tower". www.cologne-tourism.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ Arnold Wolff: Die Gefährdung des Domes und die Arbeit der Dombauhütte, in: Arnold Wolff, Toni Diederich: Das Kölner Dom Lese- und Bilderbuch, Köln 1990, p. 73.

- ^ "Köln Reporter-Kölner Dom, die Dombauhütte und die Geschichte des Kölner Wahrzeichens". www.koelnreporter.de. Archived from the original on 29 July 2024. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ Rüdiger Marco Booz: Kölner Dom, die vollkommene Kathedrale, Petersberg 2022, p. 200f

- ^ The materials used were trachyte and latite from Drachenfels, from Stenzelberg, Wolkenburg and Berkum; sandstone from Schlaitdorf, Obernkirchen and Kelheim, limestone from Krensheim and Savonnières and basalt from Mayen, Niedermendig and Londorf: Esther von Plehwe-Leisen, Elmar Scheuren, Thomas Schumacher, Arnold Wolff: Steine für den Kölner Dom; Köln 2004

- ^ "Deutschlandfunk Kultur.de: Dauerbaustelle Kölner Dom". Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ Arnold Wolff: Die Gefährdung des Domes und die Arbeit der Dombauhütte, in: Arnold Wolff, Toni Diederich: Das Kölner Dom Lese- und Bilderbuch, Köln 1990, p. 82.

- ^ dpa: Warum der Kölner Dom schwarz bleiben muss. Archived 26 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine In: DerWesten. 9. March 2015.

- ^ Arnold Wolff: Die Gefährdung des Domes und die Arbeit der Dombauhütte, in: Arnold Wolff, Toni Diederich: Das Kölner Dom Lese- und Bilderbuch, Köln 1990, p. 80.

- ^ "Koelner Dom.de: Geschichte der Kölner Dombauhütte" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ Fraunhofer IRB: Labortechnische Untersuchungen über die Wirkung von Steinschutz- und Konservierungsmitteln auf die Natursteine am Kölner Dom. In: baufachinformation.de. https://archive.today/20120719164251/http://www.baufachinformation.de/denkmalpflege.jsp?md=1988023001701

- ^ Arnold Wolff: Der Dom zu Köln. bearbeitet und ergänzt von Barbara Schock-Werner. Köln 2015, p. 10.

- ^ "e-periodica.ch". Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ "5G und Cloud: Amazon und Vodafone vereinbaren Kooperation". FAZ.NET (in German). 9 December 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ "Northdocks". northdocks.com (in German). Archived from the original on 4 March 2024. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ Wim Swaan,[page needed] Banister Fletcher[page needed]

- ^ Holladay, Joan A. (1989). "The Iconography of the High Altar in Cologne Cathedral". Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte. 52 (Bd., H. 4): 472–498. doi:10.2307/1482466. JSTOR 1482466.

- ^ "Art History". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 31 October 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2005.

- ^ Howard Hubbard

- ^ Reiner Dieckhoff: Die mittelalterliche Ausstattung des Kölner Domes, in Arnold Wolff (ed.): Der gotische Dom in Köln; Vista Point Verlag, Köln 2008, p. 47.

- ^ Baron, Salo Wittmayer. A social and religious history of the Jews, 2nd Edition, Columbia University Press, 1965, p. 174.

- ^ "Kölner Dom, Cologne, Germany". tititudorancea.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ "The Kaiser-Glocke at Cologne". The Argus. Melbourne, Vic. 12 June 1875. p. 10. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ The World Peace Bell in Newport, Kentucky is larger, but turns around its centre of mass rather than its top.

- ^ "Europe's cathedral bells ring out for peace in Ukraine". Reuters. 3 March 2022. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

Sources

[edit]- Booz, Rüdiger Marco, Kölner Dom, Die vollkommene Kathedrale, Petersberg 2022

- Swaan, Wim and Christopher Brooke, The Gothic Cathedral, Omega Books 1969, ISBN 0-907853-48-X

- Fletcher, Banister, A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method.

- Hubbard, Howard, Masterpieces of Western Sculpture, Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-23278-4

- Wolff, Arnold, Cologne Cathedral. Its History – Its Works of Arts, Verlag (editor) Kölner Dom, Cologne: 2nd edition 2003, ISBN 978-3-7743-0342-3

External links

[edit]- Cologne Cathedral

- Churches completed in 1880

- Former world's tallest buildings

- Gothic architecture in Germany

- Landmarks in Cologne

- Landmarks in Germany

- Roman Catholic cathedrals in North Rhine-Westphalia

- Tourist attractions in Cologne

- Innenstadt, Cologne

- World Heritage Sites in Germany

- Christian architecture

- 1880 establishments in Germany

- Pilgrimage churches in Germany