Founder crops: Difference between revisions

copyedit |

→List: -> →Domestication: Started converting to prose |

||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

|caption8 = '''Flax'''<br />''Linum usitatissimum'' |

|caption8 = '''Flax'''<br />''Linum usitatissimum'' |

||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''founder crops''' (or '''primary domesticates''') are the eight [[plant]] [[species]] that were [[Domestication|domesticated]] by early [[Neolithic]] farming communities in [[Southwest Asia]] and went on to form the basis of [[agriculture|agricultural]] economies across much of [[Eurasia]], including Southwest Asia, [[South Asia]], [[Europe]], and [[North Africa]]. They consist of three [[cereal]]s ([[Emmer|emmer wheat]], [[einkorn wheat]], and [[barley]]), four [[Pulse (legume)|pulses]] ([[lentil]], [[pea]], [[chickpea]], and [[Vicia ervilia|bitter vetch]]), and [[flax]]. These species were amongst the first domesticated plants in the world.<ref>{{cite book |first1=Daniel |last1=Zohary |first2= Maria |last2=Hopf |first3= Ehud |last3=Weiss|title=Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Domesticated Plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin |edition= Fourth |publisher=Oxford: University Press |year=2012 |page=139}}.</ref> |

The '''founder crops''' (or '''primary domesticates''') are the eight [[plant]] [[species]] that were [[Domestication|domesticated]] by early [[Neolithic]] farming communities in [[Southwest Asia]] and went on to form the basis of [[agriculture|agricultural]] economies across much of [[Eurasia]], including Southwest Asia, [[South Asia]], [[Europe]], and [[North Africa]]. They consist of three [[cereal]]s ([[Emmer|emmer wheat]], [[einkorn wheat]], and [[barley]]), four [[Pulse (legume)|pulses]] ([[lentil]], [[pea]], [[chickpea]], and [[Vicia ervilia|bitter vetch]]), and [[flax]]. These species were amongst the first domesticated plants in the world.<ref name=":0">{{cite book |first1=Daniel |last1=Zohary |first2= Maria |last2=Hopf |first3= Ehud |last3=Weiss|title=Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Domesticated Plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin |edition= Fourth |publisher=Oxford: University Press |year=2012 |page=139}}.</ref> |

||

The founder crops were not the only species domesticated in southwest Asia, nor were they necessarily the most important in the Neolithic period.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Arranz-Otaegui |first=Amaia |date=2021-01-01 |title=Archaeology of Plant Foods. Methods and Challenges in the Identification of Plant Consumption during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic in Southwest Asia |url=https://www.brepolsonline.net/doi/10.1484/J.FOOD.5.126401 |journal=Food and History |volume=19 |issue=1-2 |pages=79–109 |doi=10.1484/J.FOOD.5.126401 |issn=1780-3187}}</ref> Domesticated [[rye]] (''Secale cereale'') occurs in the final Epipalaeolithic strata at [[Tell Abu Hureyra]] (the earliest instance of domesticated plant species),<ref>Hillman G., Hedges R., Moore A., Colledge S., Pettitt P. New evidence of late glacial cereal cultivation at Abu Hureyra on the euphrates (2001) Holocene, 11 (4), pp. 383-393</ref> but was not common until the spread of farming into [[northern Europe]] several millennia later.<ref>G. Hillman. Late Pleistocene changes in wild plant-foods available to hunter-gatherers of the northern Fertile Crescent: possible preludes to cereal cultivation. In Harris, ed. The origins and spread of agriculture and pastoralism in Eurasia. 1996.</ref> Other plants cultivated in the Neolithic include [[Almond|sweet almond]]<ref>Ladizinsky, G. On the Origin of Almond. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 46, 143–147 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008690409554</ref> and [[Common fig|figs]].<ref>{{Cite web |date=8 June 2006 |title=Figs likely first domesticated crop |url=https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2006/06/figs-likely-first-domesticated-crop/}}</ref> |

The founder crops were not the only species domesticated in southwest Asia, nor were they necessarily the most important in the Neolithic period.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Arranz-Otaegui |first=Amaia |date=2021-01-01 |title=Archaeology of Plant Foods. Methods and Challenges in the Identification of Plant Consumption during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic in Southwest Asia |url=https://www.brepolsonline.net/doi/10.1484/J.FOOD.5.126401 |journal=Food and History |volume=19 |issue=1-2 |pages=79–109 |doi=10.1484/J.FOOD.5.126401 |issn=1780-3187}}</ref> Domesticated [[rye]] (''Secale cereale'') occurs in the final Epipalaeolithic strata at [[Tell Abu Hureyra]] (the earliest instance of domesticated plant species),<ref>Hillman G., Hedges R., Moore A., Colledge S., Pettitt P. New evidence of late glacial cereal cultivation at Abu Hureyra on the euphrates (2001) Holocene, 11 (4), pp. 383-393</ref> but was not common until the spread of farming into [[northern Europe]] several millennia later.<ref>G. Hillman. Late Pleistocene changes in wild plant-foods available to hunter-gatherers of the northern Fertile Crescent: possible preludes to cereal cultivation. In Harris, ed. The origins and spread of agriculture and pastoralism in Eurasia. 1996.</ref> Other plants cultivated in the Neolithic include [[Almond|sweet almond]]<ref>Ladizinsky, G. On the Origin of Almond. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 46, 143–147 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008690409554</ref> and [[Common fig|figs]].<ref>{{Cite web |date=8 June 2006 |title=Figs likely first domesticated crop |url=https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2006/06/figs-likely-first-domesticated-crop/}}</ref> |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

Different species formed the basis of early agricultural economies in other [[Vavilov center|centres of domestication]]. For example, rice was first cultivated in the [[Yangtze River]] basin of East Asia in the early Neolithic.<ref name="Normile">{{cite journal|last=Normile|first=Dennis|year=1997|title=Yangtze seen as earliest rice site|journal=Science|volume=275|issue=5298|pages=309–310|doi=10.1126/science.275.5298.309|s2cid=140691699}}</ref><ref>"New Archaeobotanic Data for the Study of the Origins of Agriculture in China", Zhijun Zhao, Current Anthropology Vol. 52, No. S4, (October 2011), pp. S295-S306</ref> [[Sorghum]] was widely cultivated in sub-Saharan Africa during the early Neolithic,<ref>{{Cite book |last=Carney |first=Judith |title=In the Shadow of Slavery |publisher=University of California Press |year=2009 |isbn=9780520269965 |location=Berkeley and Los Angeles, California |pages=16}}</ref> while peanuts,<ref>{{cite web |last=Dillehay |first=Tom D. |title=Earliest-known evidence of peanut, cotton and squash farming found |url=http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2007-06/vu-eeo062507.php |access-date=June 29, 2007}}</ref> squash,<ref name="smith2006">{{cite journal |last=Smith |first=Bruce D. |date=15 August 2006 |title=Eastern North America as an Independent Center of Plant Domestication |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America |volume=103 |issue=33 |pages=12223–12228 |bibcode=2006PNAS..10312223S |doi=10.1073/pnas.0604335103 |pmc=1567861 |pmid=16894156 |doi-access=free}}</ref> and [[cassava]]<ref>Olsen, KM; Schaal, BA (1999). "Evidence on the origin of cassava: phylogeography of Manihot esculenta". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (10): 5586–91. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.5586O. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.10.5586. PMC 21904. {{PMID|10318928}}</ref> were domesticated in the Americas.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/28/science/28cnd-squash.html|title=Scientists Find Earliest Sign of Cultivated Crops in Americas|newspaper=The New York Times|date=28 June 2007|last1=Wilford|first1=John Noble}}</ref> |

Different species formed the basis of early agricultural economies in other [[Vavilov center|centres of domestication]]. For example, rice was first cultivated in the [[Yangtze River]] basin of East Asia in the early Neolithic.<ref name="Normile">{{cite journal|last=Normile|first=Dennis|year=1997|title=Yangtze seen as earliest rice site|journal=Science|volume=275|issue=5298|pages=309–310|doi=10.1126/science.275.5298.309|s2cid=140691699}}</ref><ref>"New Archaeobotanic Data for the Study of the Origins of Agriculture in China", Zhijun Zhao, Current Anthropology Vol. 52, No. S4, (October 2011), pp. S295-S306</ref> [[Sorghum]] was widely cultivated in sub-Saharan Africa during the early Neolithic,<ref>{{Cite book |last=Carney |first=Judith |title=In the Shadow of Slavery |publisher=University of California Press |year=2009 |isbn=9780520269965 |location=Berkeley and Los Angeles, California |pages=16}}</ref> while peanuts,<ref>{{cite web |last=Dillehay |first=Tom D. |title=Earliest-known evidence of peanut, cotton and squash farming found |url=http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2007-06/vu-eeo062507.php |access-date=June 29, 2007}}</ref> squash,<ref name="smith2006">{{cite journal |last=Smith |first=Bruce D. |date=15 August 2006 |title=Eastern North America as an Independent Center of Plant Domestication |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America |volume=103 |issue=33 |pages=12223–12228 |bibcode=2006PNAS..10312223S |doi=10.1073/pnas.0604335103 |pmc=1567861 |pmid=16894156 |doi-access=free}}</ref> and [[cassava]]<ref>Olsen, KM; Schaal, BA (1999). "Evidence on the origin of cassava: phylogeography of Manihot esculenta". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (10): 5586–91. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.5586O. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.10.5586. PMC 21904. {{PMID|10318928}}</ref> were domesticated in the Americas.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/28/science/28cnd-squash.html|title=Scientists Find Earliest Sign of Cultivated Crops in Americas|newspaper=The New York Times|date=28 June 2007|last1=Wilford|first1=John Noble}}</ref> |

||

== |

== Domestication == |

||

All of the founder crops are native to Southwest Asia and were [[Domestication|domesticated]] in the [[Pre-Pottery Neolithic]] period,<ref name=":0" /> between 10,500 and 7500 years ago.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |year=2002 |title=Aceramic Neolithic |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of Prehistory, Volume 8: South and Southwest Asia |publisher=Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers |location= |id= |url= |access-date= |last=Banning |first=Edward B. |editor-last1=Peregrine |editor-first1=Peter N. |editor-last2=Ember |editor-first2=Melvin}}</ref> |

|||

=== Cereals === |

=== Cereals === |

||

The [[Staple crop|staple crops]] of Neolithic agriculture were [[Cereal|cereals]], which could be easily cultivated in open fields, have a high [[nutritional value]], and can be stored for long periods of time. The most important were two species of [[wheat]], [[emmer]] (''Triticum turgidum'' subsp. ''dicoccum'') and [[Einkorn wheat|einkorn]] (''Triticum monococcum'') and barley (''Triticum vulgare''), which were amongst the first species to be domesticated in the world. The wild progenitors of all three crops are [[Self-pollination|self-pollinating]], which made them easier to domesticate.<ref name=":1">{{Citation |last=Zohary |first=Daniel |title=Cereals |date=2012 |url=https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199549061.001.0001/acprof-9780199549061-chapter-3 |work=Domestication of Plants in the Old World |edition=4 |place=Oxford |publisher=Oxford University Press |doi=10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199549061.001.0001/acprof-9780199549061-chapter-3 |isbn=978-0-19-954906-1 |access-date=2022-05-06 |last2=Weiss |first2=Ehud |last3=Hopf* |first3=Maria}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* [[Einkorn wheat]] (''Triticum monococcum'', descended from the wild ''T. boeoticum'') |

|||

Wild einkorn wheat (''Triticum monococcum'' subsp. ''boeoticum'') grows across Southwest Asia in open [[Forest steppe|parkland]] and [[steppe]] environments.<ref name=":1" /> It comprises three distinct [[Race (biology)|races]], only one of which, native to [[Southeast Anatolia]], was domesticated.<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal |last=Kilian |first=B. |last2=Ozkan |first2=H. |last3=Walther |first3=A. |last4=Kohl |first4=J. |last5=Dagan |first5=T. |last6=Salamini |first6=F. |last7=Martin |first7=W. |date=2007-12 |title=Molecular diversity at 18 loci in 321 wild and 92 domesticate lines reveal no reduction of nucleotide diversity during Triticum monococcum (Einkorn) domestication: implications for the origin of agriculture |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17898361/ |journal=Molecular Biology and Evolution |volume=24 |issue=12 |pages=2657–2668 |doi=10.1093/molbev/msm192 |issn=0737-4038 |pmid=17898361}}</ref> The main feature that distinguishes domestic einkorn from wild is that its ears will not [[Shattering (agriculture)|shatter]] without pressure, making it dependent on humans for dispersal and reproduction.<ref name=":1" /> It also tends to have wider grains.<ref name=":1" /> Wild einkorn was collected at [[Epipalaeolithic]] sites such as [[Tell Abu Hureyra]] ({{Circa|12,700–11,000 years ago}}) and [[Mureybet]] ({{Circa|11,800–11,300 years ago}}), but the earliest archaeological evidence for the domestic form comes from the early [[Pre-Pottery Neolithic B]] of southern Turkey, at [[Çayönü]], [[Cafer Höyük]], and possibly [[Nevalı Çori]].<ref name=":1" /> Genetic evidence indicates that it was domesticated in multiple places independently.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

* [[Barley]] (''Hordeum vulgare/sativum'', descended from the wild ''H. spontaneum'') |

|||

Wild emmer wheat (''Triticum turgidum'' subsp. ''dicoccoides'') is less widespread that einkorn, favouring the rocky [[Basalt|basaltic]] and [[limestone]] soils found in the [[Hilly Flanks|hilly flanks]] of the Fertile Crescent.<ref name=":1" /> It is also more diverse, with domesticated varieties falling into two major groups: hulled or non-shattering, in which threshing seperates the whole [[spikelet]]; and free-threshing, where the individual grains are seperated. Both varieties probably existed in the Neolithic, but over time free-threshing cultivars became more common.<ref name=":1" /> Genetic studies have found that, like einkorn, emmer was domesticated in southeast Anatolia, but only once.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Ozkan |first=H. |last2=Brandolini |first2=A. |last3=Schäfer-Pregl |first3=R. |last4=Salamini |first4=F. |date=2002-10 |title=AFLP analysis of a collection of tetraploid wheats indicates the origin of emmer and hard wheat domestication in southeast Turkey |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12270906/ |journal=Molecular Biology and Evolution |volume=19 |issue=10 |pages=1797–1801 |doi=10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004002 |issn=0737-4038 |pmid=12270906}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Luo |first=M.-C. |last2=Yang |first2=Z.-L. |last3=You |first3=F. M. |last4=Kawahara |first4=T. |last5=Waines |first5=J. G. |last6=Dvorak |first6=J. |date=2007-04-01 |title=The structure of wild and domesticated emmer wheat populations, gene flow between them, and the site of emmer domestication |url=https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-006-0474-0 |journal=Theoretical and Applied Genetics |language=en |volume=114 |issue=6 |pages=947–959 |doi=10.1007/s00122-006-0474-0 |issn=1432-2242}}</ref> The earliest secure archaeological evidence for domestic emmer comes from the early PPNB levels at Çayönü, {{Circa|10,250–9550 years ago}}, where distinctive scars on the spikelets indicated that they came from a hulled domestic variety.<ref name=":1" /> Slightly earlier finds have been reported from [[Tell Aswad]] in Syria, {{Circa|10,500–10,200 years ago}}, but these were identified using a less reliable method based on grain size.<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

=== Pulses === |

=== Pulses === |

||

| Line 55: | Line 61: | ||

* [[Vicia ervilia|Bitter vetch]] (''Vicia ervilia'') |

* [[Vicia ervilia|Bitter vetch]] (''Vicia ervilia'') |

||

=== |

=== Flax === |

||

* [[Flax]] (''Linum usitatissimum'') |

* [[Flax]] (''Linum usitatissimum'') |

||

Revision as of 12:00, 6 May 2022

Triticum turgidum subsp. dicoccum

Triticum monococcum

Hordeum spp.

Lens culinaris

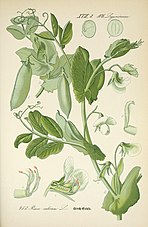

Pisum sativum

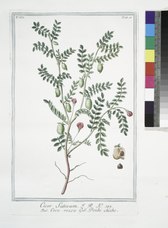

Cicer arietinum

Vicia ervilia

Linum usitatissimum

The founder crops (or primary domesticates) are the eight plant species that were domesticated by early Neolithic farming communities in Southwest Asia and went on to form the basis of agricultural economies across much of Eurasia, including Southwest Asia, South Asia, Europe, and North Africa. They consist of three cereals (emmer wheat, einkorn wheat, and barley), four pulses (lentil, pea, chickpea, and bitter vetch), and flax. These species were amongst the first domesticated plants in the world.[1]

The founder crops were not the only species domesticated in southwest Asia, nor were they necessarily the most important in the Neolithic period.[2] Domesticated rye (Secale cereale) occurs in the final Epipalaeolithic strata at Tell Abu Hureyra (the earliest instance of domesticated plant species),[3] but was not common until the spread of farming into northern Europe several millennia later.[4] Other plants cultivated in the Neolithic include sweet almond[5] and figs.[6]

Different species formed the basis of early agricultural economies in other centres of domestication. For example, rice was first cultivated in the Yangtze River basin of East Asia in the early Neolithic.[7][8] Sorghum was widely cultivated in sub-Saharan Africa during the early Neolithic,[9] while peanuts,[10] squash,[11] and cassava[12] were domesticated in the Americas.[13]

Domestication

All of the founder crops are native to Southwest Asia and were domesticated in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period,[1] between 10,500 and 7500 years ago.[14]

Cereals

The staple crops of Neolithic agriculture were cereals, which could be easily cultivated in open fields, have a high nutritional value, and can be stored for long periods of time. The most important were two species of wheat, emmer (Triticum turgidum subsp. dicoccum) and einkorn (Triticum monococcum) and barley (Triticum vulgare), which were amongst the first species to be domesticated in the world. The wild progenitors of all three crops are self-pollinating, which made them easier to domesticate.[15]

Wild einkorn wheat (Triticum monococcum subsp. boeoticum) grows across Southwest Asia in open parkland and steppe environments.[15] It comprises three distinct races, only one of which, native to Southeast Anatolia, was domesticated.[16] The main feature that distinguishes domestic einkorn from wild is that its ears will not shatter without pressure, making it dependent on humans for dispersal and reproduction.[15] It also tends to have wider grains.[15] Wild einkorn was collected at Epipalaeolithic sites such as Tell Abu Hureyra (c. 12,700–11,000 years ago) and Mureybet (c. 11,800–11,300 years ago), but the earliest archaeological evidence for the domestic form comes from the early Pre-Pottery Neolithic B of southern Turkey, at Çayönü, Cafer Höyük, and possibly Nevalı Çori.[15] Genetic evidence indicates that it was domesticated in multiple places independently.[16]

Wild emmer wheat (Triticum turgidum subsp. dicoccoides) is less widespread that einkorn, favouring the rocky basaltic and limestone soils found in the hilly flanks of the Fertile Crescent.[15] It is also more diverse, with domesticated varieties falling into two major groups: hulled or non-shattering, in which threshing seperates the whole spikelet; and free-threshing, where the individual grains are seperated. Both varieties probably existed in the Neolithic, but over time free-threshing cultivars became more common.[15] Genetic studies have found that, like einkorn, emmer was domesticated in southeast Anatolia, but only once.[17][18] The earliest secure archaeological evidence for domestic emmer comes from the early PPNB levels at Çayönü, c. 10,250–9550 years ago, where distinctive scars on the spikelets indicated that they came from a hulled domestic variety.[15] Slightly earlier finds have been reported from Tell Aswad in Syria, c. 10,500–10,200 years ago, but these were identified using a less reliable method based on grain size.[15]

Barley (Hordeum vulgare/sativum) is descended from the wild H. spontaneum.

Pulses

- Lentil (Lens culinaris)

- Pea (Pisum sativum)

- Chickpea (Cicer arietinum)

- Bitter vetch (Vicia ervilia)

Flax

- Flax (Linum usitatissimum)

See also

References

- ^ a b Zohary, Daniel; Hopf, Maria; Weiss, Ehud (2012). Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Domesticated Plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin (Fourth ed.). Oxford: University Press. p. 139..

- ^ Arranz-Otaegui, Amaia (2021-01-01). "Archaeology of Plant Foods. Methods and Challenges in the Identification of Plant Consumption during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic in Southwest Asia". Food and History. 19 (1–2): 79–109. doi:10.1484/J.FOOD.5.126401. ISSN 1780-3187.

- ^ Hillman G., Hedges R., Moore A., Colledge S., Pettitt P. New evidence of late glacial cereal cultivation at Abu Hureyra on the euphrates (2001) Holocene, 11 (4), pp. 383-393

- ^ G. Hillman. Late Pleistocene changes in wild plant-foods available to hunter-gatherers of the northern Fertile Crescent: possible preludes to cereal cultivation. In Harris, ed. The origins and spread of agriculture and pastoralism in Eurasia. 1996.

- ^ Ladizinsky, G. On the Origin of Almond. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 46, 143–147 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008690409554

- ^ "Figs likely first domesticated crop". 8 June 2006.

- ^ Normile, Dennis (1997). "Yangtze seen as earliest rice site". Science. 275 (5298): 309–310. doi:10.1126/science.275.5298.309. S2CID 140691699.

- ^ "New Archaeobotanic Data for the Study of the Origins of Agriculture in China", Zhijun Zhao, Current Anthropology Vol. 52, No. S4, (October 2011), pp. S295-S306

- ^ Carney, Judith (2009). In the Shadow of Slavery. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. p. 16. ISBN 9780520269965.

- ^ Dillehay, Tom D. "Earliest-known evidence of peanut, cotton and squash farming found". Retrieved June 29, 2007.

- ^ Smith, Bruce D. (15 August 2006). "Eastern North America as an Independent Center of Plant Domestication". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (33): 12223–12228. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10312223S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0604335103. PMC 1567861. PMID 16894156.

- ^ Olsen, KM; Schaal, BA (1999). "Evidence on the origin of cassava: phylogeography of Manihot esculenta". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (10): 5586–91. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.5586O. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.10.5586. PMC 21904. PMID 10318928

- ^ Wilford, John Noble (28 June 2007). "Scientists Find Earliest Sign of Cultivated Crops in Americas". The New York Times.

- ^ Banning, Edward B. (2002). "Aceramic Neolithic". In Peregrine, Peter N.; Ember, Melvin (eds.). Encyclopedia of Prehistory, Volume 8: South and Southwest Asia. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Zohary, Daniel; Weiss, Ehud; Hopf*, Maria (2012), "Cereals", Domestication of Plants in the Old World (4 ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199549061.001.0001/acprof-9780199549061-chapter-3, ISBN 978-0-19-954906-1, retrieved 2022-05-06

- ^ a b Kilian, B.; Ozkan, H.; Walther, A.; Kohl, J.; Dagan, T.; Salamini, F.; Martin, W. (2007-12). "Molecular diversity at 18 loci in 321 wild and 92 domesticate lines reveal no reduction of nucleotide diversity during Triticum monococcum (Einkorn) domestication: implications for the origin of agriculture". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 24 (12): 2657–2668. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm192. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 17898361.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Ozkan, H.; Brandolini, A.; Schäfer-Pregl, R.; Salamini, F. (2002-10). "AFLP analysis of a collection of tetraploid wheats indicates the origin of emmer and hard wheat domestication in southeast Turkey". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 19 (10): 1797–1801. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004002. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 12270906.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Luo, M.-C.; Yang, Z.-L.; You, F. M.; Kawahara, T.; Waines, J. G.; Dvorak, J. (2007-04-01). "The structure of wild and domesticated emmer wheat populations, gene flow between them, and the site of emmer domestication". Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 114 (6): 947–959. doi:10.1007/s00122-006-0474-0. ISSN 1432-2242.

Further reading

- Daniel Zohary, Maria Hopf, Ehud Weiss (2012). Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Domesticated Plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin. Fourth edition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850356-3