North Sea: Difference between revisions

made new page to add in |

removed one citation which duplicated within the same sentence |

||

| Line 119: | Line 119: | ||

| accessdate = 2007-07-20 }}</ref> |

| accessdate = 2007-07-20 }}</ref> |

||

The [[Silver Pit]] is a valley-like depression 45 km (27 mi) east of [[Spurn Head]] in England that has been recognised for hundreds of years by fishermen. Nearby is the [[Silverpit crater]], a controversial structure initially proposed to be an [[impact crater]],<ref name="pit">{{cite web| url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/4360815.stm| title=North Sea crater shows its scars| publisher=[[BBC]]| date=18 March 2005| author=Jonathan Amos| accessdate=2008-11-02}}</ref> |

The [[Silver Pit]] is a valley-like depression 45 km (27 mi) east of [[Spurn Head]] in England that has been recognised for hundreds of years by fishermen. Nearby is the [[Silverpit crater]], a controversial structure initially proposed to be an [[impact crater]], though other geologists interpret it to be the result of the dissolution of a thick bed of [[salt]] which permitted the upper strata to collapse.<ref name="pit">{{cite web| url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/4360815.stm| title=North Sea crater shows its scars| publisher=[[BBC]]| date=18 March 2005| author=Jonathan Amos| accessdate=2008-11-02}}</ref> [[Devil's Hole (North Sea)|Devil's Hole]] is a group of trenches, around 130 m (425 ft) deeper than the surrounding sea floor, about 200 km (125 mi) east of [[Dundee]], [[Scotland]].<ref>{{cite journal| journal=The Edinburgh Geologist| issue=14| month=November | year=1983| title=The Devil's Hole in the North Sea| author=Alan Fyfe| url=http://www.edinburghgeolsoc.org/edingeologist/z_14_04.html/| accessdate=2008-11-02}}</ref> |

||

| publisher=BBC News |

|||

| author=Jonathan Amos |

|||

| title =North Sea crater shows its scars |

|||

| date =18 March 2005 |

|||

| url =http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/4360815.stm |

|||

| accessdate = 2008-11-02}}</ref> [[Devil's Hole (North Sea)|Devil's Hole]] is a group of trenches, around 130 m (425 ft) deeper than the surrounding sea floor, about 200 km (125 mi) east of [[Dundee]], [[Scotland]].<ref>{{cite journal| journal=The Edinburgh Geologist| issue=14| month=November | year=1983| title=The Devil's Hole in the North Sea| author=Alan Fyfe| url=http://www.edinburghgeolsoc.org/edingeologist/z_14_04.html/| accessdate=2008-11-02}}</ref> |

|||

"The [[Long Forties]]" denotes an area of the northern North Sea that is fairly consistently forty [[fathom]]s (73 m) deep (thus, on a [[nautical chart]] with depth shown in fathoms, a long area with many "40" notations). It is located between the northeast coast of Scotland and the southwest coast of Norway, centred about {{coord|57|00|00|N|0|30|0|E|type:landmark|display=inline|name=Long Forties}}. The [[Broad Fourteens]] are an area of the southern North Sea that is fairly consistently fourteen fathoms (26 m) deep (thus a broad area with many "14" notations). It is located off the coast of the Netherlands and south of the Dogger Bank, roughly between {{coord|53|30|00|N|0|3|0|E|type:landmark|display=inline|name=Broad Fourteens North east}} and {{coord|52|30|00|N|4|30|0|E|type:landmark|display=inline|name=Broad Fourteens South west}}. |

"The [[Long Forties]]" denotes an area of the northern North Sea that is fairly consistently forty [[fathom]]s (73 m) deep (thus, on a [[nautical chart]] with depth shown in fathoms, a long area with many "40" notations). It is located between the northeast coast of Scotland and the southwest coast of Norway, centred about {{coord|57|00|00|N|0|30|0|E|type:landmark|display=inline|name=Long Forties}}. The [[Broad Fourteens]] are an area of the southern North Sea that is fairly consistently fourteen fathoms (26 m) deep (thus a broad area with many "14" notations). It is located off the coast of the Netherlands and south of the Dogger Bank, roughly between {{coord|53|30|00|N|0|3|0|E|type:landmark|display=inline|name=Broad Fourteens North east}} and {{coord|52|30|00|N|4|30|0|E|type:landmark|display=inline|name=Broad Fourteens South west}}. |

||

| Line 253: | Line 247: | ||

| location = |

| location = |

||

| date = April 1992 |

| date = April 1992 |

||

| url = http:// |

| url = http://www.springerlink.com/content/f730864308572020/ |

||

| doi = 10.1007/BF02665747 |

| doi = 10.1007/BF02665747 |

||

| id = |

| id = |

||

Revision as of 01:03, 29 November 2008

| North Sea | |

|---|---|

| Location | Atlantic Ocean |

| Coordinates | 56°N 03°E / 56°N 3°E |

| Primary inflows | Forth, Ythan, Elbe, Weser, Ems, Rhine/Waal, Meuse, Scheldt, Spey, Tay, Thames, Humber, Tees, Wear, Tyne |

| Basin countries | Norway, Denmark, Germany, Netherlands, Belgium, France and the U.K. (England, Scotland) |

| Max. length | Template:Km to mi[1] |

| Max. width | Template:Km to mi[1] |

| Surface area | Template:Km2 to mi2[1] |

| Average depth | Template:M to ft[1] |

| Max. depth | Template:M to ft[1] |

| Water volume | Template:Km3 to mi3[1] |

| Salinity | 3.4 - 3.5 % |

| Max. temperature | Template:C to F[1] |

| Min. temperature | Template:C to F[1] |

The North Sea is a marginal, epeiric sea of the Atlantic Ocean on the European continental shelf. It is more than 970 kilometres (600 mi) long and 560 kilometres (350 mi) wide, with an area of around 570,000 square kilometres (220,000 sq mi). A large part of the European drainage basin empties into the North Sea including water from the Baltic Sea. The North Sea connects with the rest of the Atlantic through the Dover Strait and the English Channel in the south and through the Norwegian Sea in the north.

Much of the sea's coastal features are the result of glacial movements. Deep fjords and sheer cliffs mark the Norwegian and parts of the Scottish coastline, whereas the southern coasts consist of sandy beaches and mudflats. These flatter areas are particularly susceptible to flooding, especially as a result of storm tides. Elaborate systems of dikes have been constructed to protect coastal areas.

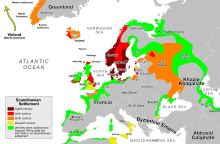

The development of European civilisation has been heavily affected by the maritime traffic on the North Sea. The Romans and the Vikings sought to extend their territory across the sea. The Hanseatic League, the Netherlands, and finally the British sought to dominate commerce on the North Sea and through it to access the markets and resources of the world. Commercial enterprises, growing populations, and limited resources gave the nations on the North Sea the desire to control or access it for their own commercial, military, and colonial ends.

In recent decades, its importance has turned away from the military and geopolitical to the purely economic. Traditional economic activities, such as fishing and shipping, have continued to grow and other resources, such as fossil fuels and wind energy, have been discovered and developed.

Geography

The North Sea is bounded by the east coasts of England and Scotland to the west and the northern and central European mainland to the east and south, including Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France.[2] In the south-west, beyond the Straits of Dover, the North Sea becomes the English Channel. In the east, it connects to the Baltic Sea via the Skagerrak and Kattegat, narrow straits that separate Denmark from Norway and Sweden respectively. In the north, it opens in a widening funnel shape to the Norwegian Sea, which lies in the very north-eastern part of the Atlantic.

Apart from the obvious boundaries formed by the coasts, the North Sea is generally considered to be bounded by an imaginary line from Lindesnes, Norway to Hanstholm, Denmark running towards the Skagerrak. However, for statistical purposes, the Skagerrak and the Kattegat are sometimes included as part of the North Sea.[3][4] The northern limit is less well-defined. Traditionally, an imaginary line is taken to run from northern Scotland, by way of Shetland, to Ålesund in Norway.[5] According to the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic of 1962 it runs further to the west and north from longitude 5° West and latitude 62° North, at the latitude of Geirangerfjord in Norway.[6]

The surface area of the North Sea is approximately Template:Km2 to mi2[1] with a volume of around Template:Km3 to mi3.[1] This places the North Sea at the 13th largest sea on the planet.[7] Around the edges of the North Sea are sizable islands and archipelagos, including Shetland, Orkney, and the Frisian Islands.

Submarine topography

For the most part, the sea lies on the European continental shelf. The only exception is the Norwegian trench, which reaches from the Stad peninsula in Sogn og Fjordane to the Oslofjord. The trench is between Template:NM to km - Template:NM to km wide and hundreds of metres deep.[6] Off the Rogaland coast, it is 250 - 300 m (820-980 ft) deep, and at its deepest point, off Arendal, it reaches 700 m (2300 ft) deep as compared to the average depth of the North Sea, about 100 m (325 ft).[1] The trench is not a subduction-related oceanic trench, where one tectonic plate is being forced under another. It is mainly a deep erosional scour, while the western part follows the North-South line of an old Rift Valley formed during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods.

To the east of Great Britain, lies the Dogger Bank, a vast moraine, or accumulation of unconsolidated glacial debris, which rises up to 15 to 30 m (50 - 100 ft) deep.[8]

The Silver Pit is a valley-like depression 45 km (27 mi) east of Spurn Head in England that has been recognised for hundreds of years by fishermen. Nearby is the Silverpit crater, a controversial structure initially proposed to be an impact crater, though other geologists interpret it to be the result of the dissolution of a thick bed of salt which permitted the upper strata to collapse.[9] Devil's Hole is a group of trenches, around 130 m (425 ft) deeper than the surrounding sea floor, about 200 km (125 mi) east of Dundee, Scotland.[10]

"The Long Forties" denotes an area of the northern North Sea that is fairly consistently forty fathoms (73 m) deep (thus, on a nautical chart with depth shown in fathoms, a long area with many "40" notations). It is located between the northeast coast of Scotland and the southwest coast of Norway, centred about 57°00′00″N 0°30′0″E / 57.00000°N 0.50000°E. The Broad Fourteens are an area of the southern North Sea that is fairly consistently fourteen fathoms (26 m) deep (thus a broad area with many "14" notations). It is located off the coast of the Netherlands and south of the Dogger Bank, roughly between 53°30′00″N 0°3′0″E / 53.50000°N 0.05000°E and 52°30′00″N 4°30′0″E / 52.50000°N 4.50000°E.

Name

The North Sea was named by the Frisians, who have inhabited the south-west coast of Denmark and northwest coasts of Germany and the Netherlands since pre-Roman times. Other seas that they named in relation to their own territory include the East Sea (Oostzee, the Baltic Sea) and two which have since been wholly or partly reclaimed, the South Sea (Zuiderzee, today's IJsselmeer) and Middle Sea (Middelzee). In mediaeval times the spread of maps used by Hanseatic merchants popularised the name ""North Sea" throughout Europe and it was adopted by German and Spanish writers (Mar del Norte in Spanish).[11]

Other common names in use for long periods were the Latin terms Mare Frisia, and Mare Frisicum, Oceanum- or Mare Germanicum as well as their English equivalents, "Frisian Sea", "German Ocean", "German Sea" and "Germanic Sea" (from the Latin Mare Germanicum).[12][13][13] By the late nineteenth century, these names were rare, scholarly usages.[13]

History

Early history

The first records of marine traffic on the North Sea come from the Roman Empire, which began exploring the sea in 12 BC. Great Britain was formally invaded in 43 AD and its southern areas incorporated into the Empire, beginning sustained trade across the North Sea and the English Channel. The Romans abandoned Britain in 410 and in the power vacuum they left, the Germanic Angles, Saxons, and Jutes began the next great migration across the North Sea during the Migration Period, conquering, displacing, and mixing with the native Celtic populations.[14]

The Viking Age began in 793 with the attack on Lindisfarne[15] and for the next quarter-millennium the Vikings ruled the North Sea. In their superior longships, they raided, traded, and established colonies and outposts on the Sea's coasts.

From the middle ages through the 15th century, the north European coastal ports exported domestic goods, dyes, linen, salt, metal goods and wine. The Scaninavian and Baltic areas shipped grain, fish, naval necessities, and timber. From the Mediterranean in this era would be high grade cloths, spices, and fruits.[16] Commerce during this era was mainly undertaken by maritime trade due to underdeveloped roadways.[16] The Burgundian Netherlands, French Netherlands, Spanish Netherlands and Austrian Netherlands and German lands were a central focus for trade situated on the banks of the North Sea or the English Channel. Antwerp experienced its golden age as the Netherlands surged ahead to be the main economic power of the 16th century.[16]

Trade on the North Sea came to be controlled by the Hanseatic League which monopolised the Northern Isles export trade.[16] The League, though centred on the Baltic Sea, had important members and outposts on the North Sea. Goods from all over the world flowed through the North Sea on their way to and from the Hanseatic cities. By the 16th Century, the League had been substantially weakened as neighbouring states took control of former Hanseatic cities and outposts and internal conflict prevented effective cooperation and defence.[17] Furthermore, the League lacked colonies as shipping began to focus on providing Europe with Asian, American, and African goods.

Early modern history

Dutch power saw its zenith during her Golden Age in the 17th century. During this era they had expanded their herring, cod and whale fisheries to an all time high.[16] Important overseas colonies, a vast merchant marine, and a powerful navy made the Dutch the main rivals of growing England, which saw its future in these three spheres. This conflict was at the root of the first three Anglo-Dutch Wars between 1652 and 1673. Despite Dutch victories in these wars and others, the ascension of the Dutch prince William to the English throne, caused a dramatic shift in commercial, military, and political power from Amsterdam to London.[18] By the end of the War of Spanish Succession in 1714, the Dutch were no longer a major player in European politics.

Scotland emerged as a prominent economic power during the Scottish Enlightenment of the 18th century. The advancements of this era established a great herring fishing industry resulting in Scotland becoming a European leader.[16]

Between 1700 and 1815, the North Sea saw only 45 years of peace, and could be regarded as the most dangerous eras to sail the sea.[19] In the late 1700s, Britain's naval supremacy faced a new challenge from Napoleonic France and her continental allies. In 1800, a union of lesser naval powers, called the League of Armed Neutrality, was formed to protect neutral trade during Britain's conflict with France. The British Navy defeated the combined forces of the League of Armed Neutrality in the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801 in the Kattegat.[20] French plans for an invasion of Britain were focused on the English Channel, but a series of mishaps and a decisive British naval victory in the Battle of Trafalgar (1805), off the coast of Spain, put them to rest. After Napoleon's exile in 1815, Britain's naval superiority preserved the Pax Britannica. Several conflicts involved interruptions in maritime trade in the North Sea, though none which had decisive effects on the wars' outcomes: the French and British cut off Russia's Baltic ports during the Crimean War and the First and Second Schleswig Wars saw Prussia's coasts blockaded, as did the Franco-Prussian War. The British did not face a challenge to their dominance of the North Sea until World War One broke out in 1914.

20th Century

Tensions in the North Sea were again heightened in 1904 by the Dogger Bank incident, in which Russian naval vessels mistook British fishing boats for Japanese ships and fired on them, and then upon each other. The incident, combined with Britain's alliance with Japan and the Russo-Japanese War led to an intense diplomatic crisis. The crisis was defused when Russia was defeated by the Japanese and agreed to pay compensation to the fishermen.[21]

During the First World War, Great Britain's Grand Fleet and Germany's Kaiserliche Marine faced each other on the North Sea, which became the main theatre of the war for surface action. Britain's larger fleet was able to establish an effective blockade for most of the war that restricted the Central Powers' access to many crucial resources. Major battles included the Battle of Heligoland Bight, the Battle of the Dogger Bank, the Battle of Jutland, and the Second Battle of Heligoland Bight. Britain, though not always tactically successful, maintained the blockade and thus kept the High Seas Fleet in port. Conversely, the German navy remained a threat that kept the vast majority of Britain's capital ships in the North Sea.[22] World War One was also the first in which submarine warfare was used extensively and a number of submarine actions occurred in the North Sea, including the sinking of the Pathfinder, the first combat victory of a modern submarine,[23] and the exploits of U-9, which sank three British cruisers in under an hour, establishing the submarine as an important new component of naval warfare.[24]

The Second World War also saw action in the North Sea, though it was restricted more to submarines and smaller vessels such as minesweepers, and torpedo boats and similar vessels.[25]

In the last years of the war and the first years thereafter, hundreds of thousands of tons of weapons were disposed of by being sunk in the North Sea.[26]

After the war, the North Sea lost much of its military significance because it is bordered only by NATO member-states. However, it gained significant economic importance in the 1960s as the states on the North Sea began full-scale exploitation of its oil and gas resources. The North Sea continues to be an active trade route.[27]

Political status

The countries bordering the North Sea all claim the Template:NM to km of territorial waters within which they have exclusive fishing rights.[28] The Common Fisheries Policy of the European Union (EU) exists to coordinate fishing rights and assist with disputes between EU states and the EU border state of Norway.[29]

After the discovery of mineral resources in the North Sea, Norway claimed its rights under the Convention on the Continental Shelf. The other countries on the sea followed suit. These rights are largely divided along the median line. The median line is defined as the line "every point of which is equidistant from the nearest points of the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea of each State is measured.[30]" The ocean floor border between Germany, the Netherlands, and Denmark was only reapportioned after protracted negotiations and a judgment of the International Court of Justice.[31][32]

Geology

History of the coastlines

Shallow epicontinental seas like the current North Sea have since long existed on the European continental shelf. The rifting that formed the northern part of the Atlantic Ocean during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, from about 150 million years ago, caused tectonic uplift in the British Isles.[33] Since then a shallow sea has almost continuously existed between the highs of the Fennoscandian Shield and the British Isles.[34] This precursor of the current North Sea has grown and shrunk with the rise and fall of the eustatic sea level during geologic time. Sometimes it was connected with other shallow seas, such as the sea above the Paris Basin to the southwest, the Paratethys Sea to the southeast, or the Tethys Ocean to the south.[35]

During the Late Cretaceous, about 85 million years ago, all of modern mainland Europe except for Scandinavia was a scattering of islands.[36] By the Early Oligocene, 34 to 28 million years ago, the emergence of Western and Central Europe had almost completely separated the North Sea from the Tethys Ocean, which gradually shrank to become the Mediterranean Sea as Southern Europe and South West Asia became dry land.[37] The North Sea was cut off from the English Channel by a narrow land bridge until that was breached by at least two catastrophic floods between 450,000 and 180,000 years ago.[38][39][40] Since the start of the Quarternary period about 2.6 million years ago, the eustatic sea level has fallen during each glacial period and then risen again. Every time the ice sheet reached its greatest extent, the North Sea became almost completely dry. The present-day North Sea coastline formed when, after the Last Glacial Maximum (the peak of the glaciation during the last ice age) 20,000 years ago, the sea began to flood the European continental shelf.[41] The Cenozoic era covers the period from 65.5 million years ago and is still ongoing. The North Sea coastline still undergoes changes following earthquakes, storm surges, the rise and fall of sea levels, shingle drifts as well as the deposition of sands and clastics in paralic environments.[35]

photo credit Tomasz G. Sienicki

Biology and the environment

Fish and Shellfish

Copepods and other zooplankton are plentiful in the North Sea. These tiny organisms are crucial elements of the food chain supporting many species of fish. The North Sea is home to about 230 species of fish. Cod, haddock, whiting, saithe, plaice, sole, mackerel, herring, pouting, sprat, and sandeel are all very common and the target of commercial fishing.[42] Due to the various depths of the North Sea trenches and differences in salinity, temperature, and water movement, some fish reside only in small areas of the North Sea. The blue-mouth redfish and rabbitfish are examples of these.[43]

Crustaceans are also commonly found throughout the sea. Norway lobster, deep-water prawns, and brown shrimp are all commercially fished, but other species of lobster, shrimp, oyster, mussels and clams are all found. Recently non-indigenous species have become established including the Pacific oyster and Atlantic jackknife clam.[42]

Birds

The coasts of the North Sea are home to nature reserves including the Ythan Estuary, Fowlsheugh Nature Preserve, and Farne Islands in the UK and The Wadden Sea National Parks in Germany. These locations provide breeding habitat for dozens of bird species. Tens of millions of birds make use of the North Sea for breeding, feeding, or migratory stopovers every year. Populations of Northern fulmars, Black-legged Kittiwakes, Atlantic puffins, razorbills, and species of petrels, gannets, seaducks, loons (divers), cormorants, gulls, auks, and terns, and many other seabirds make these coasts popular for birdwatching.[42]

Marine mammals

Photo credit Peter Asprey

The North Sea is also home to marine mammals. Common seals, grey seals can be found along the coasts, at marine installations, and on islands. The very northern North Sea islands like the Shetlands are occasionally home to a larger variety of pinnipeds including bearded, harp, hooded and ringed seals, and even walrus.[44] North Sea cetaceans include Harbour porpoises, common dolphins, bottlenose dolphins, Risso's dolphins, long-finned pilot whales and white-beaked dolphins, minke whales, killer whales, and sperm whales.[45]

Flora

Plant species in the North Sea include species of wrack, among them bladder wrack, knotted wrack, and serrated wrack. Algae, including kelp, such as oarweed and laminaria hyperboria, and species of maerl are found as well.[42] Many plants are harvested commercially, for the production of alginate, pharmaceuticals, and fertilizer. Eelgrass, formerly common in the entirety of the Wadden Sea, was nearly wiped out in the 20th century by a disease and has struggle to reestablish itself. Similarly, sea moss used to coat huge tracts of ocean floor, but have been damaged by trawling and dredging have diminished its habitat and prevented its return.[46] Invasive Japanese seaweed has spread along the shores of the sea, growing up to 10 m (33 ft) long and sometimes clogging harbours.

Biodiversity and Conservation

Historically, flamingos, pelicans, and Great Auk could be found along the southern shores of the North Sea.[47] Gray whale also resided in the North Sea but were driven to extinction in the Atlantic in the 1600s. Other species have seen dramatic declines in population, though they are still to be found; right whales, sturgeon, shad, rays, skates and salmon among other species were common in the North Sea into the 20th Century, when numbers declined.

A variety of factors have contributed to decreasing populations of North Sea fauna. The introduction of non-indigenous species, industrial and agricultural pollution, overfishing and trawling, dredging, human-induced eutrophication, construction on coastal breeding and feeding grounds, sand and gravel extraction, offshore construction, and heavy shipping traffic all threaten marine life in the North Sea.[42]

In recent decades, action has been taken by the border countries to address many of these threats. The OSPAR convention was created in 1992 as and expansion of the 1972 Oslo Convention. It is managed by the OSPAR commission and has taken action to counteract the harmful effects of human activity on wildlife in the North Sea and preserve many endangered species. All North Sea border states are signatories of the MARPOL 73/78 Accords. Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands also have a trilateral agreement for the protection of the Wadden Sea, or mudflats, which run along the coasts of the three countries on the southern edge of the North Sea.

Hydrology

Basic data

The water temperature of the North Sea varies depending on the influence of the Atlantic currents, depth, and season, generally reaching 21 °C (77 °F) in summer and 6 °C (50 °F) in winter, though Arctic currents can be colder. The eastern side is both the warmest in summer and the coldest in winter. In the deeper northern North Sea, the water remains a nearly constant 10 °C (50 °F) year round because of water exchange with the Atlantic. The greatest temperature variations are found on the very shallow Wadden Sea coast, where sea ice can form in very cold winters.[7]

The salinity of the water is also dependent on place and time of year, but it is generally in the range of 15 to 25 parts per thousand (ppt) around river mouths and up to 32 to 35 ppt in the northern North Sea[7] — lower than the average North Atlantic salinity of around 35 ppt.

The exchange of salt water between the North Sea and Atlantic occurs through the English Channel, in the northern North Sea along the Scottish coast, and through the Norwegian Sea. The North Sea receives freshwater not only from rivers but also from the low-salinity Baltic Sea, which drains into the North Sea via the Skagerrak. The North Sea rivers drain a land area of 841,500 km² (324,905 sq mi) and supply 296-354 km³ (71-85 cu mi) of fresh water annually. The Baltic rivers drain almost twice as large an area (1,650,000 km², 637,068 sq mi) and contribute 470 km³ (113 cu mi) of fresh water annually.[7]

Around 185 million people live in the catchment area of the rivers that flow into the North Sea.[48] These rivers drain a large part of Northern Europe: a quarter of France, three quarters of Germany, nearly all of Switzerland, half of Denmark, the whole of the Netherlands and Belgium, the southern part of Norway, the Rhine basin of western Austria and the eastern side of Great Britain.[48] This area contains one of the world's greatest concentrations of industry.

Water circulation

The main pattern to the flow of water in the North Sea is a counter-clockwise rotation along the edges.[49] Water from the Gulf Stream flows in both through the English Channel towards Norway, and around the north of Britain, moving south along the British coast. From the south-moving current smaller currents are pulled off eastwards into the central North Sea. Another significant current sweeps south in the eastern part of the Sea. This is cold North Atlantic water and is strongest in late spring and early summer when the British offshore waters remain cool while the sea off the Netherlands and Germany starts warming up. Water from the Channel, and water flowing out of the Baltic Sea eventually move north along the Norwegian coast back into the Atlantic in what is called the Norwegian Current.[50] The current moves at a depth of 50 to 100 m (165-330 ft). It has a relatively low salinity due to the brackish water of the Baltic and the fresh water contributed by the rivers and the fjords. Though the current is, on average, cooler than the North Sea water as a whole, warmer water flowing in from the Channel mixed with the cooler waters of the Baltic and North Atlantic result in streams of widely varying temperatures within the current.

The mean residence time of water in the North sea is between one and two years.[50] Water in the north is exchanged most quickly while water in the German Bight can circulate for years before being pulled northwards.

Bodies of water characterised by the same temperature, salinity, nutrients, and pollution can be clearly identified; they are more clearly defined in summer than in winter. Large fronts are the Frisian Front, which divides water coming from the North Atlantic from water originating in the English Channel, and the Danish Front, which divides southern coastal waters from water in the central North Sea. The inflow of water from large rivers mixes very slowly with North Sea water. Water from the Rhine and Elbe, for example, can still be clearly differentiated from sea water off the northwest coast of Denmark.

| River | Country | Discharge in m³/s | in cu ft/s |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhine / Meuse | Netherlands | 2,524 | 89,134 |

| Elbe | Germany | 856 | 30,229 |

| Glomma | Norway | 603 | 21,295 |

| IJsselmeer | Netherlands | 555 | 19600 |

| Weser | Germany | 358 | 12,643 |

| Skjern Å | Denmark | 206 | 7275 |

| Firth of Tay (includes River Tay and River Earn) | Scotland | 203 | 7169 |

| Moray Firth (includes River Spey and River Ness) | Scotland | 168 | 5933 |

| Scheldt | Belgium/Netherlands | 126 | 4450 |

| Humber | England | 125 | 4415 |

| Forth | Scotland | 112 | 3955 |

| Ems | Germany | 88 | 3108 |

| Tweed | England | 85 | 3002 |

| Thames | England | 76 | 2684 |

Tides

The North Sea has very strong and unusual tides. They are caused by the tide wave from the North Atlantic, as the sea itself is too small and too flat to have its own tides. Ebb and flow alternate in a cycle of 12.5 hours. The tide wave, owing to the Coriolis effect, flows around Scotland and then counter-clockwise along the English coast, reaching the German Bight some 12 hours after arriving in Scotland. In so doing, it runs around three amphidromic points, places where the tidal range is very near zero, around which tides rotate. One such point lies northeast of the Straits of Dover. It is formed by the tide wave which is transported through the English Channel. It influences the tides in the narrow area in the Southern Bight between southern England and the Netherlands. A second amphidromic system, which affects most of the Sea consists of two points near each other, which form a tide wave. The two other points just off the coast of southern Norway and lying on a line between southern Denmark and the West Frisian Islands form a single area around which the tides flow. Its central point lies off the coast of Denmark.

As a result, the tidal range in southern Norway is less than half a metre (1.5 ft), but increases the further any given coast lies from the amphidromic point.[51] Shallow coasts and the funnel effect of narrow straits increase the tidal range. The tidal range is at its greatest at The Wash on the English coast, where it reaches Template:M to ft.[52] In shallow water areas, the real tidal range is strongly influenced by other factors, such as the position of the coast and the wind at any given moment or the action of storms. In river estuaries, high water levels can considerably amplify the effect of high tide.

Coasts

The eastern and western coasts of the North Sea are jagged, as they were stripped by glaciers during the ice ages. The coastlines along the southernmost part are soft, covered with the remains of deposited glacial sediment, which was left directly by the ice or has been redeposited by the sea. The Norwegian mountains plunge into the sea, giving birth, north of Stavanger, to deep fjords and archipelagos. South of Stavanger, the coast softens, the islands become fewer. The eastern Scottish coast is similar, though less severe than Norway. Starting from Flamborough Head in the northeast of England, the cliffs become lower and are composed of less resistant moraine, which erodes more easily, so that the coasts have more rounded contours. In Holland, Belgium and in the east of England (East Anglia) the littoral is low and marshy. The east coast and south-east of the North Sea (Wadden Sea) have coastlines that are mainly sandy and straight owing to longshore currents, particularly along Belgium and Denmark.[53]

Northern fjords, skerries, and cliffs

Photo credit Frédéric de Goldschmid

The northern North Sea coasts bear the impression of the enormous glaciers which covered them during the Ice Ages and created a split, craggy coastal landscape. Fjords arose by the action of glaciers, which dragged their way through them from the highlands, cutting and scraping deep trenches in the land. During the subsequent rise in sea level, they filled with water. They very often display steep coastlines and are extremely deep for the North Sea. Fjords are particularly common on the coast of Norway.[54]

Firths are similar to fjords, but are generally shallower with broader bays in which small islands may be found. The glaciers that formed them influenced the land over a wider area and scraped away larger areas. Firths are to be found mostly on the Scottish and northern English coasts. Individual islands in the firths, or islands and the coast, are often joined up by sandbars or spits made up of sand deposits known as “tombolos”.[55][56]

Towards the south the firths give way to a cliff coast, which was formed by the moraines of Ice Age glaciers.[57] The horizontal impact of waves on the North Sea coast gives rise to eroded coasts. The eroded material is an important source of sediment for the mudflats on the other side of the North Sea.[58] The cliff landscape is interrupted in southern England by large estuaries with their corresponding mud and marshy flats, notably the Humber and the Thames.

There are skerries in southern Norway and on the Swedish Skagerrak coast.[59] Formed by similar action to that which created the fjords and firths, the glaciers in these places affected the land to an even greater extent, so that large areas were scraped away. The coastal brim (Strandflaten), which is found especially in southern Norway, is a gently sloping lowland area between the sea and the mountains. It consists of plates of bedrock, and often extends for kilometres, reaching under the sea, at a depth of only a few metres.

Southern shoals and mudflats

The shallow-water coasts of the southern and eastern coast up to Denmark were formed by Ice Age activity, but their particular shape is determined for the most part by the sea and sediment deposits.[60] The Wadden Sea stretches between Esbjerg, Denmark in the north and Den Helder, Netherlands in the west. This landscape is heavily influenced by the tides and important sections of it have been declared a National Park. The whole of the coastal zone is shallow; the tides flood large areas and uncover them again, constantly depositing sediments. The Southern Bight has been especially changed by land reclamation, as the Dutch have been especially active. The largest project of this type was the diking and reclamation of the IJsselmeer.

In the micro tidal area, (a tidal range of up to 1.35 m (4.43 ft)), such as on the Dutch or Danish coasts,[61] barrier beaches with dunes are formed. In the mesotidal area (a tidal range of between 1.35 and 2.90 m (4.43-9.5 ft)), barrier islands are formed; in the macrotidal area (above 2.90 m (9.5 ft) tidal range), such as at the mouth of the Elbe, underwater sandbanks form.

The Dutch West Frisian and the German East Frisian Islands are barrier islands. They arose along the breakers’ edge where the water surge piled up sediment, and behind which sediment was carried away by the breaking waves. Over time, sandplates arose, which finally were only covered by infrequent storm floods. Once plants began to colonise the sandbanks the land began to stabilise.[62]

The North Frisian Islands, on the other hand, arose from the remains of old Geestland islands, where the land was partially removed by storm floods and water action and then separated from the mainland. They are, therefore, often higher and their cores are less exposed to changes than the islands to the south. Beyond the core, however, the same processes are at work, particularly evident on Sylt, where the south of the island threatens to be broken away, while the harbour at List in the north silts up.[63] The Danish Islands, the next in the chain to the north, arose from sandbanks. Right up into the twentieth century, the silting up of the islands was a serious problem. To protect the islands, small woods were planted.

The small, historically strategic island of Heligoland was not formed by sediment deposition; it is considerably older and is composed of Early Triassic sandstone.

Storm tides

Photo credit Tom Corser

Storm tides threaten, in particular, the coasts of the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, and Denmark. These coasts are quite flat, so even a relatively small increase in the water levels is sufficient to put large stretches of land under water. Storms from the west are especially strong, so the most dangerous places are on the south-east coast. Over the years, floods caused by storm tides have cost hundreds of thousands of lives and have significantly helped to shape the coast. Until early modern times, the recorded number of victims from a single storm tide could be in the tens of thousands, even exceeding a hundred thousand, though to what extent these historically-reported casualties are accurate can only be estimated with difficulty.

The Storegga Slides were a series of underwater landslides, in which a piece of the Norwegian continental shelf slid into the Norwegian Sea. The immense landslips occurred between 8150 BC and 6000 BC, and caused a tsunami up to 20 m (65 ft) high that swept through the North Sea, having the greatest effect on Scotland and the Faeroe Islands.[64][65]

The first recorded storm tide flood was the Julianenflut, on 17 February 1164.[66] In its wake the Jadebusen began to form. Ancient records tell also of the First Marcellus Flood, which struck West Friesland in 1219. A storm tide in 1228 is recorded to have killed more than 100,000 people. In 1362, the Second Marcellus Flood, also known as the Grote Mandrenke, hit the entire southern coast of the North Sea. Chronicles of the time again record more than 100,000 deaths as large parts of the coast were lost permanently to the sea, including the now legendary lost city of Rungholt.

The coastline of the North Sea changed again following the flood of 1825; the Jutland Peninsula is now called the North Jutlandic Island.[67][68] The Dover Straits earthquake of 1580 is among the first recorded earthquake in the North Sea and caused extensive damage in both France and England both through its tremors and a tsunami. The largest earthquake ever recorded in the United Kingdom was the 1931 Dogger Bank earthquake, which measured 6.1 on the Richter Scale and caused a tsunami that flooded parts of the British coast.[69][70] In the twentieth century, the North Sea flood of 1953 flooded several nations' coasts and cost more than 2,000 lives.[71] 315 citizens of Hamburg died in the North Sea flood of 1962. The "Century Flood" of 1976 and the "North Frisian Flood" of 1981 brought the highest water levels measured to date on the North Sea coast, but because of the dikes built and improved after the flood of 1962, these led only to property damage.[72] A storm surge occurred on November 9, 2007, causing flooding. The conditions were likened to those that had caused the damage and large loss of life in 1953. Fortunately, in 2007, nowhere near as much damage was caused, though the Thames Barrier was closed twice to protect London.

Coastal preservation

Photo credit Johann H. Addicks/Wikipedia

Photo credit Donar Reiskoffer

The southern coastal areas were originally amphibious. The land included countless islands and islets which had been divided by rivers, streams, and wetlands and areas of dry land were regularly flooded. In areas especially vulnerable to storm tides, people settled first on natural areas of high ground such as spits and Geestland. As early as 500 BC, people were constructing artificial dwelling hills several metres high. It was only around the beginning of the High Middle Ages, in 1200 AD, that inhabitants began to connect single ring dikes into a dike line along the entire coast, thereby turning amphibious regions between the land and the sea into permanent solid ground.

The modern form of the dikes began to appear in the 17th and 18th centuries, built by private enterprises in the Netherlands. The Dutch dike builders exported their designs to other North Sea regions. The North Sea Floods of 1953 and 1962 were impetus for further raising of the dikes as well as the shortening of the dike line through land reclamation and river weirs so as to present as little surface area as possible to the punishment of the sea and the storms.[73] Currently, 27% of the Netherlands is below sea level protected by dikes, dunes, and beach flats.[74]

Coastal preservation today consists of several levels. The dike slope reduces the energy of the incoming sea, so that the dike itself does not receive the full impact. Dikes that lie directly on the sea are especially reinforced. The dikes have, over the years, been repeatedly raised, sometimes up to 10 m (32 ft) and have become flatter in order to better reduce the erosion of the waves.[75] Modern dikes are up to 100 m (328 ft) across. Behind the dike, there generally runs an access road and a thinly inhabited area. In many places, another dike follows after several kilometres.

Where the dunes are sufficient to protect the land behind them from the sea, these dunes are planted with beach grass to protect them from erosion by wind, water, and foot traffic.[76]

Economy

Oil and gas

Photo credit: Erik Christensen

As early as 1859, oil was discovered in onshore areas around the North Sea and natural gas as early as 1910.[36] In 1958, geologists discovered a natural gas field in Slochteren in the Dutch province of Groningen and it was suspected that more fields lay under the North Sea. However, at this point, the rights to natural resource exploitation on the high seas were still under dispute.[77]

Test drilling began in 1966 and, then in 1969, Phillips Petroleum Company discovered the Ekofisk oil field (now Norwegian), which at that point was one of the 20 largest in the world and turned out to be distinguished by valuable, low-sulphur oil. Commercial exploitation began in 1971 with tankers and after 1975 by a pipeline first to Teesside, England and then, after 1977, also to Emden, Germany.[78]

The exploitation of the North Sea oil reserves began just before the 1973 oil crisis, and the climb of international oil prices made the large investments needed for extraction much more attractive. In the 1980s and 1990s, further discoveries of large oil fields followed. Although the production costs are relatively high, the quality of the oil, the political stability of the region, and the nearness of important markets in western Europe has made the North Sea an important oil producing region. The largest single humanitarian catastrophe in the North Sea oil industry was the destruction of the offshore oil platform Piper Alpha in 1988 in which 167 people lost their lives.[79] The fires on the Piper Alpha burned off most of the hydrocarbons on board and released from the disrupted wells. However, a major blowout in 1977 in the Ekofisk field resulted in oil flowing unimpeded into the sea for a week before it was capped; estimates of the amount of oil released to the environment vary between 86,000 and 202,380 barrels (between 10,000 to 30,000 tonnes, depending on the density of the oil).[80]

Besides the Ekofisk oil field, the Statfjord oil field is also notable as it was the cause of the first pipeline to span the Norwegian trench.[81] The largest natural gas field in the North Sea, Troll Field, lies in the Norwegian trench at a depth of 345 metres (1100 ft) requiring the construction of the enormous Troll A platform to access it.[82]

In 1999, extraction reached an all time high with nearly 6 million barrels (950,000 m³) of crude oil and 280,000,000 m³ (999,000,000 cu ft) of natural gas per day.[83] The Danish explorations of Cenozoic stratigraphy undertaken in the 1990s showed petroleum rich reserves in the northern Danish sector especially the Central Graben area.[84] The Dutch area of the North Sea followed through with onshore and offshore gas exploration and well creation.[85][86]

The price of Brent Crude, one of the first types of oil extracted from the North Sea, is used today as a standard price for comparison for crude oil from the rest of the world.[87]

Fishing

Photo credit: Dirk Ingo Franke

Fishing in the North Sea is concentrated in the southern part of the coastal waters. The main method of fishing is trawling.

Annual catches grew each year until the 1980s, when a high point of more than 3 million metric tons (3.3 million S/T) was reached. Since then, the numbers have fallen back to around 2.3 million tons (2.5 million S/T) annually with considerable differences between years. Besides the fish caught, it is estimated that 150,000 metric tons (165,000 S/T) of unmarketable by-catch are caught and around 85,000 metric tons (94,000 S/T) of dead and injured invertebrates.[88]

In recent decades, overfishing has left many fisheries unproductive, disturbing the marine food chain dynamics and costing jobs in the fishing industry.[89] Herring, cod and plaice fisheries may soon face the same plight as mackerel fishing which ceased in the 1970s due to overfishing.[90] Since the 1960s, various regulations have attempted to protect the stocks of fish such as limited fishing times and limited numbers of fishing boats, among other regulations. However, these rules were never systematically enforced and did not bring much relief. Since then, the United Kingdom and Denmark, two important fishing nations, became members of the EU, and have attempted, with the help of the Common Fisheries Policy, to bring the problem under control.[91]

Mineral resources

In addition to oil, gas, and fish, the states along the North Sea also take millions of cubic metres per year of sand and gravel from the ocean floor. These are used for construction projects, sand for beaches, and coast protection. The largest extractor of sand and gravel in 2003 was far and away the Netherlands (around 30 million m³ {322 million sq ft) with Denmark a distant second (around 10 million m³ {110 million sq ft} from the North Sea).[92]

Rolled pieces of amber, usually small but occasionally of very large size, may be picked up on the east coast of England, having probably been washed up from deposits under the North Sea. Cromer is the best-known locality, but it occurs also on other parts of the Norfolk coast, such as Great Yarmouth, as well as Southwold, Aldeburgh and Felixstowe in Suffolk, and as far south as Walton-on-the-Naze in Essex, whilst northwards it is not unknown in Yorkshire. On the other side of the North Sea, amber is found at various localities on the coast of the Netherlands and Denmark.[93] Amber was also found on the Baltic coast across northern Europe. Some of the amber districts of the Baltic and North Sea were known in prehistoric times, and led to early trade with the south of Europe along the so-called Amber Road.

Renewable energy

Photo credit Leonard G.

Due to the strong prevailing winds, countries on the North Sea, particularly England and Denmark, have used the areas near the coast of the sea for wind driven electricity production since the 1990s. Offshore wind turbines appeared first off the English coast near Blyth in 2000 and then off the Danish coast in 2002 near Horns Rev. Others have been commissioned, including Windpark Egmond aan Zee (OWEZ) and Scroby Sands and more are in the planning phase. Offshore wind farms have met some resistance. Concerns have arisen about shipping collisions and damage to the ocean ecology, particularly by the construction of the foundations. Furthermore, the distance from consumers leads to considerable energy losses in transmission.[94] Nonetheless, the first deep water turbines in Scotland are under commission for Talisman Energy, who are installing two large machines 25 km (15 mi) offshore adjacent to the Beatrice oilfield. These turbines are 88 m (290 ft) high with the blades 63 m (210 ft) long and will have a capacity of 5 megawatts (MW) each, making them the largest in the world.[95][96]

Energy production from the sea itself is still in a pre-commercial stage. The southern parts of the North Sea, do not have sufficient tidal range to harness energy usefully. The Norwegian coast and the intersection with the Irish Sea could be found suitable for waves or ocean currents to provide power. The European Marine Energy Centre (EMEC) based at Stromness in Orkney is a Scottish Government-backed research facility. They have installed a wave testing system at Billia Croo on the Orkney mainland[97] and a tidal power testing station on the nearby island of Eday.[98] Since 2003, a Wave Dragon overtopping system prototype for harnessing wave power is deployed in Nissum Bredning, a fjord in the northern part of Denmark[99]

Tourism

The beaches and coastal waters of the North Sea are popular destinations for tourists. The Belgian, Dutch, German, and Danish coasts are especially developed for tourism. While many of the busiest British beach resorts are on the south coast, the British east coast also has important beach resorts.

Windsurfing and sailing are popular sports because of the strong winds. Mudflat hiking, recreational fishing, diving — including wreck diving, and birdwatching are among other popular activities.

The climatic conditions on the North Sea coast are often claimed to be especially healthful. As early as the 19th century travellers used their stays on the North Sea coast as curative and restorative vacations (German:Kur-Urlaub). The sea air, temperature, wind, water, and sunshine are counted among the beneficial conditions that are said to activate the body's defences, improve circulation, strengthen the immune system, and have healing effects on the skin and the respiratory system.[100][101] Besides the climate, thalassotherapy spas use sea waters, mud, brine, algae, and sea salt for curative and restorative purposes.[102]

One peculiarity of the North Sea tourism until the 1990s was the Butterfahrten or butter rides. These were trips past the German tariff barriers onto the high seas for the purpose of purchasing items much more cheaply than they could be bought in Germany itself. The name comes from the time when butter was an expensive commodity and could be purchased more cheaply from Denmark. Other important wares were the heavily taxed goods like tobacco, spirits, and perfume.[103]

Marine traffic

Photo credit Quistnix

The North Sea is very important for marine traffic and experiences some of the densest concentrations of ships in the world. Great ports are located along its coasts: Rotterdam, the third busiest port in the world by tonnage, Antwerp and Hamburg, both in the top 25, Bremen/Bremerhaven and Felixstowe, both in the top 30 busiest container seaports,[104] as well as the Port of Bruges-Zeebrugge, Europe's leading RoRo port.

All major ports have easy access to the various sea lanes of the North Sea, which are monitored, well-regulated, and regularly dredged. Traffic in the North Sea can be difficult. Fishing boats, oil and gas platforms as well as merchant traffic from Baltic ports share routes on the North Sea. The possibility of bottlenecks at the Dover Strait, which sees more than 400 vessels a day[105] and the Kiel Canal, which averages more than 100 per day plus sport traffic (2003 figure)[106] can add to the difficulty.

The North Sea coasts are home to numerous canals and canal systems to facilitate traffic between and among rivers, artificial harbours, and the sea. The Kiel Canal, connecting the North Sea with the Baltic Sea, is the most heavily used artificial seaway in the world.[107] It opened on June 20, 1895[108] and saves an average of Template:NM to km, instead of the voyage around the Jutland Peninsula.[107] The North Sea Canal connects Amsterdam with the North Sea.

See also

- Doggerland

- List of languages of the North Sea

- North Sea Commission

- Principality of Sealand

- Geography Portal

- Nautical Portal

Further reading

- Bridging Troubled Waters : Conflict and Co-operation in the North Sea Region since 1550 (2005, ISBN 8790982304)

- Ilyina, P Ilyina (2007) The fate of persistent organic pollutants in the North Sea. Springer. ISBN 9783540681625)

- Karlsdóttir, Hrefna M (2005) Fishing on common grounds : the consequences of unregulated fisheries of North Sea herring in the postwar period. ISBN 9185196622)

- North Sea coast: landscape panoramas (2007, ISBN 9781877339653)

- Rural History in the North Sea Area A State of the Art. (2007, ISBN 9782503510057)

- Mesolithic studies in the North Sea Basin and beyond : proceedings of a conference held at Newcastle in 2003 (2007, ISBN 1842172247)

- Offshore wind energy in the North Sea Region : the state of affairs of offshore wind energy projects, national policies and economic, environmental and technological conditions in Denmark, Germany, The Netherlands, Belgium and the United Kingdom (2005, OCLC: 71640714)

Footnotes

- Ziegler, P.A.; 1990: Geological Atlas of Western and Central Europe, Shell Internationale Petroleum Maatschappij BV (2nd ed.), ISBN 90-6644-125-9.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "About the North Sea: Key facts". Safety at Sea. Design by Tvers. Developed by WebCat. 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ^ De Angelo, Laura (August 22, 2008). "North Sea, Europe - Encyclopedia of Earth". Environmental Information Coalition, National Council for Science and the Environment). Retrieved 2008-11-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Forum Skagerrak II Database". Forum Skagerrak II. Retrieved 2008-11-02."The Skagerrak together with the Kattegat is a transitional area between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea. Normally the Skagerrak is understood to be a part of the North Sea while the Kattegat according to the HELCOM constitutes part of the Baltic Sea area."

- ^ "Kattegat definition". Babylon Ltd. 1997–2008. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link)"The Kattegat is a continuation of the Skagerrak and may be seen as either a bay of the Baltic Sea, a bay of the North Sea, or, in traditional Scandinavian usage, none of these. " - ^ Lehfeldt, R. "Propagation of a Tsunami-wave in the North Sea" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-11-24.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)Northern boundary of the North Sea between Wick (Scotland) and Stavanger (Norway) - ^ a b "LIS No. 10 - North Sea 1974" (pdf). U.S. Department of State. United States Government. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ^ a b c d Management Unit of the North Sea Mathematical Models (2002–2008). "North Sea facts". Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. Retrieved 2007-07-19.

- ^ Dogger Bank, Maptech Online MapServer, 1989 - 2008, retrieved 2007-07-20

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Jonathan Amos (18 March 2005). "North Sea crater shows its scars". BBC. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ^ Alan Fyfe (1983). "The Devil's Hole in the North Sea". The Edinburgh Geologist (14). Retrieved 2008-11-02.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Peterson, Mark (2005). "Naming the Pacific". Common-place. 5 (2). The Interactive Journal of Early American Life. Retrieved 2007-07-19.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Redbad (November 30, 1998). "History of the Frisian Folk". Retrieved 2008-11-23.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Buijtenen, M. P. Van. "JSTOR: De grondslag van de Friese vrijheid". Speculum, Vol. 29, No. 3 (Jul., 1954), pp. 620-621. Medieval Academy of America. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Cite error: The named reference "Buijtenen" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Germany - People, Encyclopædia Britannica <--no other fuller citation available-->, 02 Nov. 2008, retrieved 2007-07-24

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Nick Atwood (2006), The Viking Raid on Lindisfarne, Lindisfarne.org.uk, retrieved 2008-11-02

- ^ a b c d e f Smith, H.D. (April 1992). "The British Isles and the Age of Exploration - A Maritime Perspective". GeoJournal. 26 (4): 483–487. doi:10.1007/BF02665747. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Hanseatic League, howstuffworks.com, 2008, retrieved 2008-11-02

- ^ Short History of the Anglo Dutch Wars, The Contemplator, retrieved 2008-11-02

- ^ "historical background". Norwegian University of Science and Technology. NTNU. 2005.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Claus Christiansen (1997), War with England 1801-1804, Danish Military History, retrieved 2008-11-02

- ^ Dogger Bank: Voyage of the Damned, Hullwebs, 2004, retrieved 2008-11-02

{{citation}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Smith, Gordon (1999–2008), North Sea in Outline 1914-1918, Naval-History.net, retrieved 2008-11-02

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Story of the U-21, National Underwater and Marine Agency, retrieved 2008-11-02

- ^ Helgason, Guðmundur (2008), U 9, Uboat.net, retrieved 2008-11-02

- ^ Atlantic, WW2, U-boats, convoys, OA, OB, SL, HX, HG, Halifax, RCN ..., Naval-History.net, retrieved 2007-07-24

- ^ Koch, Marc; Ruck, Wolfgang, Securing and Remediation Concepts for Dumped Chemical and Conventional Munitions in the Baltic Sea (PDF), retrieved 2007-10-26

- ^ Forth Ports PLC (html), 2008, retrieved 2007-11-11

- ^ Barry, Michael. "Governing the North Sea in the Netherlands" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-11-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ About the Common Fisheries Policy, European Commission, 24 January 2008, retrieved 2008-11-02

- ^ Convention on the Continental Shelf, Geneva., The Multilaterals Project, The Fletcher School, Tufts University, 29 April 1958, retrieved 2007-07-24

- ^ North Sea Continental Shelf Cases, International Court of Justice, Judgment of 20 February 1969, retrieved 2007-07-24

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Barry, M. Governing the North Sea in the Netherlands (pdf). Administering Marine Spaces: International Issues. International Federation of Surveyors. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ziegler, P. A. "AAPG/Datapages, Inc. DOI Citation". Geologic Evolution of North Sea and Its Tectonic Framework. doi:10.1306/83D91F2E-16C7-11D7-8645000102C1865D. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ See Ziegler (1990) or Glennie (1998) for the development of the paleogeography around the North Sea area from the Jurassic onwards

- ^ a b Torsvik, Trond H. (November 2004). "Global reconstructions and North Atlantic paleogeography 440 Ma to Recen" (PDF). Retrieved November 19, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Glennie, KW (1998), Petroleum Geology of the North Sea: Basic Concepts and Recent Advances, Blackwell Publishing, pp. 11–12, ISBN 9780632038459 =

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Smith, A.G. (2004). Atlas of Mesozoic and Cenozoic Coastlines. Cambridge University Press. pp. 27–38. ISBN 0521602874. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ^ Gibbard, P. (July 2007). "Palaeogeography: Europe cut adrift". Nature. 448: 259–260.

{{cite journal}}: Text "doi:10.1038/448259a" ignored (help) - ^ Gupta, Sanjeev; Collier, Jenny S.; Palmer-Felgate, Andy; Potter, Graeme (2007), "Catastrophic flooding origin of shelf valley systems in the English Channel", Nature, 448: 342–346.

- ^ Europe cut adrift", by Philip Gibbard, pp 259-260, Nature, vol 448, 19 July 2007

- ^ Sola, M. A. (2000). "Geological Exploration in Murzuq Basin". A contribution to IUGS/IAGC Global Geochemical Baselines. Elsevier Science B.V., then Google books. ISBN 0-4444-50611-X. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e "Quality Status Report for the Greater North Sea" (pdf). Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR). 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ^ Factors affecting the distribution Of North Sea fish (pdf), International Council for the Exploration of the Sea ICES, retrieved 2007-12-09

- ^ Marine mammals in the waters of the north sea, The North Sea Bird Club, 11 December 2002, retrieved 2007-12-21

- ^ Whales and dolphins in the North Sea 'on the increase', Newcastle University Press Release, 2 April 2005, retrieved 2007-12-21

- ^ "Effects of Trawling and Dredging on Seafloor Habitat". Ocean Studies Board (OSB). National Academy of Sciences. 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "296 - The Dykes of Doggerland". Strange Maps. July 2, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ^ a b Quality Status Report 2000 for the North-East Atlantic, Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR), 2 November 2008, retrieved 2007-12-21

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ "Met Office: Flood alert!". Met office UK government. 2006-11-28. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b "Currents in the North Sea". Safety At Sea. 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ^ Tett, Paul (19 February 2003). "Marine Biology 2. Water layering and water movements". School of Life Sciences,. Napier University. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Murby, Paul (1997). "The Wash Natural Area Profile" (PDF). English Nature. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Verwaest, Toon (19–23 September 2005). "Windows in the dunes – the creation of sea inlets in the nature reserve de Westhoek in De Panne" (pdf). in Herrier J.-L., J. Mees, A. Salman, J. Seys, H. Van Nieuwenhuyse and I. Dobbelaere (Eds) Proceedings ‘Dunes and Estuaries 2005’ – International Conference on Nature Restoration Practices in European Coastal Habitats. Koksijde, Belgium: Flanders Marine Institute (VLIZ). pp. p. 433-439. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

{{cite conference}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ International EMECS Center (2003). Environmental Guidebook 5: North Sea (pdf). International Center for the Environmental Management of Enclosed Coastal Seas (EMECS). Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ May, V.J. and Hansom, J.D. (2003). Coastal Geomorphology of Great Britain (pdf). Geological Conservation Review Series, No. 28. Peterborough: Joint Nature Conservation Committee. pp. 754 pp. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hansom, J.D. "St Ninian's Tombolo" (pdf). volume 28: Coastal Geomorphology of Great Britain from Geological Conservation Review Chapter 8: Sand spits and tombolos. Joint Nature Conservation Committee: 5pp. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|doi_brokendate=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Development of the East Riding Coastline" (pdf). East Riding of Yorkshire Council. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ "Action plan for Mudflats". UK Biodiversity Group Tranche 2 Action Plans Volume V: Maritime species and habitats. Joint Nature Conservation Committee. 1999. pp. p.179. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

{{cite web}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Drömresan, Micke W (1997–2005), Sailing in Sweden and the Baltic, retrieved 2007-07-24

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ "Bridlington to Skegness: Habitat: Earth heritage". Natural England. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ Hollebrandse, Florenz A.P. "Temporal development of the tidal range in the southern North Sea" (PDF). Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences. Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "North Frisian Islands". WorldAtlas.com. 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ Ahrendt, Kai, Expected Effects of Climatic Change on a Barrier Island - Case Study Sylt Island/German Bight (PDF), retrieved 2007-07-24

- ^ Axel Bojanowski, (October 11, 2006). "Tidal Waves in Europe? Study Sees North Sea Tsunami Risk". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Bondevik, Stein (2003). "Record-breaking Height for 8000-Year-Old Tsunami in the North Atlantic" (PDF). EOS, Transactions of the American Geophysical Union. 84 (31): 289, 293. Retrieved 2007-01-15.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Storm tide / Natural catastrophe - Economy-point.org". Economy-point.org. 2006. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Jutland Peninsula: North Sea". Retriever > Regional > Denmark > North Jutland. Lycos Inc. 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Vendsyssel-Thy -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia". 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ A tsunami in Belgium?, Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, 2005, retrieved 2008-11-02

- ^ Today in Earthquake History June 7, U.S. Geological Survey, 2008, retrieved 2008-11-02

- ^ Coastal Flooding: The great flood of 1953, Investigating Rivers, retrieved 2007-07-24

- ^ Lamb, Hubert (2005). Historic Storms of the North Sea, British Isles and Northwest Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521619319.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "North Sea Protection Works - Seven Modern Wonders of World". Compare Infobase Limited. 2006–2007. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Rosenberg, Matt (January 30 2007). "Dykes of the Netherlands". About.com - Geography. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 2007-07-19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Martin, Susan Taylor (November 6, 2005). "To live below sea level, ask Dutch". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ^ "Dune Grass Planting". A guide to managing coastal erosion in beach/dune systems - Summary 2. Scottish Natural Heritage. 2000. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ^ Hugo Manson (12 June 2006). "Brief History of North Sea Oil and Gas". Department of History, University of Aberdeen. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ "Ekofisk". Norwegian Petroleum Directorate. 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ^ "On This Day 6 July 1988: Piper Alpha oil rig ablaze". BBC. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ^ "Ekofisk Bravo Platform Blowout". Oil Rig Disasters. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ^ "Statpipe Rich Gas". Gassco. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ^ Craig Glenday (11 October 2006). "Guinness World Records Reaches New Depths..." Guinness World Records. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ^ Morton, Glenn R. "An Analysis of the UK North Sea Production". Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- ^ Konradi, P. (February 2005). "Cenozoic stratigraphy in the Danish North Sea Basin" (PDF). Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland,. Netherlands Journal of Geosciences — Geologie en Mijnbouw. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Text "109 - 111" ignored (help); Text "2005" ignored (help); Text "84 – 2" ignored (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "Gas exploration in Dutch sector North Sea - Ascent Resources plc". Retrieved November 19, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Hanze F2A, Dutch North Sea, Netherlands". offshore-technology.com is a product of SPG Media Limited. SPG Media Limited, a subsidiary of SPG Media Group PLC. 2008. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "North Sea Brent Crude". Investopedia ULC. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ^ International Fishmeal and Fish Oil Organisation (2004). "Evidence for Inquiry into the Scottish Fishing Industry" (PDF). Royal Society of Edinburgh. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Clover, Charles (2004). The End of the Line: How overfishing is changing the world and what we eat. London: Ebury Press. ISBN 0-09-189780-7.

- ^ "North Sea Fish Crisis - Our Shrinking Future". part 1. Greenpeace. c1997. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ North Sea Fish Stocks: Good and Bad News (pdf), International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, 18 October 2004, retrieved 2007-07-19

- ^ "New zoning information for England ..." (PDF). European Marine Sand And Gravel Group. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- ^ "Geographic Occurence of Amber". World of Amber. 2004. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ^ Offshore Wind Turbine Pictures, Danish Wind Industry Association, 13 May 2004, retrieved 2007-07-24

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ "Beatrice Wind Farm Demonstrator Project: FAQ" (PDF). Talisman Energy. 2006-02-14. Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- ^ "Worlds Largest Wind Turbine Generator". Renewable Energy. Retrieved 2007-02-14.

- ^ "Billia Croo Test Site". EMEC. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ^ "Fall of Warness Test Site". EMEC. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ^ "Prototype testing in Denmark". Wave Dragon. 2005. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ^ Büsum: The natural healing power of the sea, German National Tourist Board, retrieved 2008-11-02

- ^ Beauty and Health Derived from the Sea, Spa Hotel Sternhagen, 2007–2008, retrieved 2008-11-02

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ SPA – “Sanus Per Aquam”, Healing Treatment utilising Sea Water, Spa Hotel Sternhagen, 2007–2008, retrieved 2008-11-02

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Hemetsberge, Paul (2002 - 2008). "dict.cc dictionary :: Butterfahrt :: English-German translation". Retrieved 2008-11-02.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "World Port Rankings" (XLS). American Association of Port Authorities. 2006. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ^ "The Dover Strait". Maritime and Coastguard Agency. 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ^ "Kiel Canal Annual Report" (PDF). 2000. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ^ a b "Kiel Canal". Kiel Canal. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ^ "North Sea Canal Opened". The New York Times. 21 June 1895. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

External links

- See Interactive Map over Oil and Gas Resoources in the North Sea

- Etymology and History of names

- North Sea Commission Environment Group Member Profiles 2006

- Old map : Manuscript chart of the North Sea, VOC, ca.1690 (high resolution zoomable scan)

- Template:PDFlink

- Silver Pit chart

- The Jurassic-Cretaceous North Sea Rift Dome and associated Basin Evolution

- OSPAR Commission Homepage an international commission designed to protect and conserve the North-East Atlantic and its resources

- The Physical Geography of Western Europe By Eduard A. Koster

- North Sea Region Programme 2007-2013 a transnational cooperation Programme under the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF)