Pathophysiology of multiple sclerosis: Difference between revisions

→Pathology: typos |

Juansempere (talk | contribs) This is already in pathology, but having available biomarkers it also has to be in pathophysiology. |

||

| Line 200: | Line 200: | ||

Response to therapy is heterogeneous in MS. Serum cytokine profiles have been proposed as biomarkers for response to Betaseron<ref>{{cite journal | author = Hegen Harald | year = 2016 | title = Cytokine profiles show heterogeneity of interferon-β response in multiple sclerosis patients | url = | journal = Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm | volume = 3 | issue = 2| page = e202 | doi = 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000202 |display-authors=etal}}</ref> and the same was proposed to MxA mRNA.<ref>Matas et al. MxA mRNA expression as a biomarker of interferon beta response in multiple sclerosis patients. J Neuroimmunol. 2016 Feb 15;291:73-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.12.015. Epub 2015 Dec 30.</ref> |

Response to therapy is heterogeneous in MS. Serum cytokine profiles have been proposed as biomarkers for response to Betaseron<ref>{{cite journal | author = Hegen Harald | year = 2016 | title = Cytokine profiles show heterogeneity of interferon-β response in multiple sclerosis patients | url = | journal = Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm | volume = 3 | issue = 2| page = e202 | doi = 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000202 |display-authors=etal}}</ref> and the same was proposed to MxA mRNA.<ref>Matas et al. MxA mRNA expression as a biomarker of interferon beta response in multiple sclerosis patients. J Neuroimmunol. 2016 Feb 15;291:73-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.12.015. Epub 2015 Dec 30.</ref> |

||

==Demyelination patters== |

|||

===Demyelination patterns=== |

|||

Four different damage patterns have been identified in patient's brain tissues. The original report suggests that there may be several types of MS with different immune causes, and that MS may be a family of several diseases. Though originally was required a biopsy to classify the lesions of a patient, since 2012 it is possible to classify them by a blood test<ref>F. Quintana et al., Specific Serum Antibody Patterns Detected with Antigen Arrays Are Associated to the Development of MS in Pediatric Patients, Neurology, 2012. Freely available at [http://www.neurology.org/cgi/content/meeting_abstract/78/1_MeetingAbstracts/S60.006]</ref> looking for antibodies against 7 lipids, three of which are cholesterol derivatives<ref>Harnesing the clinical value of biomarkers in MS, International Journal of MS care, June 2012 [http://ijmsc.org/doi/pdf/10.7224/1537-2073-14.S5.1]</ref> |

|||

It is believed that they may correlate with differences in disease type and prognosis, and perhaps with different responses to treatment. In any case, understanding lesion patterns can provide information about differences in disease between individuals and enable doctors to make more accurate treatment decisions |

|||

According to one of the researchers involved in the original research "Two patterns (I and II) showed close similarities to T-cell-mediated or T-cell plus antibody-mediated autoimmune encephalomyelitis, respectively. The other patterns (III and IV) were highly suggestive of a primary oligodendrocyte dystrophy, reminiscent of virus- or toxin-induced demyelination rather than autoimmunity." |

|||

The four identified patterns are:<ref name=brainpat96>{{cite journal | author = Lucchinetti CF1 Brück W, Rodriguez M, Lassmann H | date = Jul 1996 | title = Distinct patterns of multiple sclerosis pathology indicates heterogeneity on pathogenesis | url = | journal = Brain Pathol | volume = 6 | issue = 3| pages = 259–74 | pmid = 8864283 | doi=10.1111/j.1750-3639.1996.tb00854.x}}</ref> |

|||

; Pattern I : The scar presents [[T-cells]] and [[macrophages]] around blood vessels, with preservation of [[oligodendrocyte]]s, but no signs of [[complement system]] activation.<ref>{{cite web| url=http://immserv1.path.cam.ac.uk/~immuno/part1/lec10/lec10_97.html| title=Part 1B Pathology: Lecture 11 - The Complement System| accessdate=2006-05-10| first=Nick| last=Holmes| date=15 November 2001}}</ref> |

|||

; Pattern II : The scar presents T-cells and macrophages around blood vessels, with preservation of oligodendrocytes, as before, but also signs of [[complement system]] activation can be found.<ref>{{cite journal| url=http://brain.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/122/12/2279| journal=Brain| volume=122| issue=12| pages=2279–2295|date=December 1999| title=A quantitative analysis of oligodendrocytes in multiple sclerosis lesions - A study of 113 cases| first=Claudia| last=Lucchinetti| author2=Wolfgang Brück, Joseph Parisi, Bernd Scheithauer, Moses Rodriguez and Hans Lassmann| accessdate=2006-05-10| doi=10.1093/brain/122.12.2279| pmid=10581222}}</ref> This pattern has been considered similar to damage seen in NMO, though AQP4 damage does not appear in pattern II MS lesions<ref>{{cite journal | pmid = 19822791 | doi=10.1001/archneurol.2009.199 | volume=66 | issue=10 | title=Humoral pattern II multiple sclerosis pathology not associated with neuromyelitis Optica IgG | pmc=2767176 |date=October 2009 | author=Kale N, Pittock SJ, Lennon VA | journal=Arch Neurol | pages=1298–9 | displayauthors=etal }}</ref> Nevertheless, pattern II has been reported to respond to [[plasmapheresis]],<ref name="Wilner AN, Goodman">{{cite journal |author=Wilner AN, Goodman |title=Some MS patients have "Dramatic" responses to Plasma Exchange |journal=Neurology Reviews |volume=8 |issue=3 |date=March 2000 |url=http://www.neurologyreviews.com/mar00/nr_mar00_MSpatients.html}}</ref> which points to something pathogenic into the blood serum. |

|||

:The [[complement system]] infiltration in these cases convert this pattern into a candidate for research into autoimmune connections like anti-[[Kir4.1]], <ref name="ReferenceA">Srivastava R. et Al, Potassium channel KIR4.1 as an immune target in multiple sclerosis, N Engl J Med. 2012 Jul 12;367(2):115-23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110740, PMID 22784115</ref> anti-[[Calcium-activated chloride channel | Anoctamin-2]]<ref>Burcu Ayoglu et al. Anoctamin 2 identified as an autoimmune target in multiple sclerosis, February 9, 2016, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518553113, PNAS February 23, 2016 vol. 113 no. 8 2188-2193 [http://www.pnas.org/content/113/8/2188.abstract]</ref> or [[antiMOG associated encephalomyelitis|anti-MOG mediated MS]]<ref>{{cite journal | author = Spadaro Melania | year = 2015 | title = Histopathology and clinical course of MOG-antibody-associated encephalomyelitis | url = | journal = Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology | volume = 2 | issue = 3| pages = 295–301 | doi = 10.1002/acn3.164 |display-authors=etal}}</ref> About the last possibility, research has found antiMOG antibodies in some pattern-II MS patients.<ref>Jarius S, Metz I, König FB, Ruprecht K, Reindl M, Paul F, Brück W, Wildemann B.Screening for MOG-IgG and 27 other anti-glial and anti-neuronal autoantibodies in 'pattern II multiple sclerosis' and brain biopsy findings in a MOG-IgG-positive case. Mult Scler. 2016 Feb 11. pii: 1352458515622986.</ref> |

|||

:Pattern II pathogenic T cells have already been cloned and prepared for further studies.<ref name="Planas"/><ref name="Antel J. P., Ludwin S. K., Bar-Or A. 2015 873–874"/> The functional characterization shows that T cells releasing Th2 cytokines and helping B cells dominate the T-cell infiltrate in pattern II brain lesions.<ref name="Planas"/> |

|||

; Pattern III : The scars are diffuse with inflammation, distal [[oligodendrogliopathy]] and [[microglia]]l activation. There is also loss of [[myelin-associated glycoprotein]] (MAG). The scars do not surround the blood vessels, and in fact, a rim of preserved myelin appears around the vessels. There is evidence of partial remyelinization and oligodendrocyte apoptosis. For some researchers this pattern is an early stage of the evolution of the others.<ref name=Barnett/> For others, it represents ischaemia-like injury with a remarkable availability of a specific biomarker in CSF<ref>Hans Lassmann et al. A new paraclinical CSF marker for hypoxia‐like tissue damage in multiple sclerosis lesions, Oxford Journals Medicine Brain Volume 126, Issue 6 Pp. 1347-1357</ref><ref>Christina Marik , Paul A. Felts , Jan Bauer , Hans Lassmann , Kenneth J. Smith, Lesion genesis in a subset of patients with multiple sclerosis: a role for innate immunity? Brain, DOI:10.1093/brain/awm236 2800-2815</ref> |

|||

; Pattern IV : The scar presents sharp borders and [[oligodendrocyte]] degeneration, with a rim of normal appearing [[white matter]]. There is a lack of oligodendrocytes in the center of the scar. There is no complement activation or MAG loss. |

|||

These differences are noticeable only in early lesions<ref>{{cite journal |author=Breij EC, Brink BP, Veerhuis R |title=Homogeneity of active demyelinating lesions in established multiple sclerosis |journal=Annals of Neurology |volume=63 |issue=1 |pages=16–25 |year=2008 |pmid=18232012 |doi=10.1002/ana.21311 |displayauthors=etal }}</ref> and the heterogeneity was controversial during some time because some research groups thought that these four patterns could be consequence of the age of the lesions.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Michael H. Barnett, MBBS and John W. Prineas, MBBS |title=Relapsing and Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: Pathology of the Newly Forming Lesion |journal=Annals of Neurology |volume=55 |issue=1 |pages=458–468 |year=2004 |pmid=15048884 |doi=10.1002/ana.20016|url=http://www.cpnhelp.org/files/Ref1_Annals04.pdf}}</ref> Nevertheless, after some debate among research groups, the four patterns model is accepted and the exceptional case found by Prineas has been classified as NMO<ref>{{cite journal | author = Brück W, Popescu B, Lucchinetti CF, Markovic-Plese S, Gold R, Thal DR, Metz I | date = Sep 2012 | title = Neuromyelitis optica lesions may inform multiple sclerosis heterogeneity debate | url = | journal = Ann Neurol | volume = 72 | issue = 3| pages = 385–94 | doi = 10.1002/ana.23621 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Arnold P, Mojumder D, Detoledo J, Lucius R, Wilms H | date = Feb 2014 | title = Pathophysiological processes in multiple sclerosis: focus on nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 and emerging pathways | url = | journal = Clin Pharmacol | volume = 6 | issue = | pages = 35–42 | doi = 10.2147/CPAA.S35033 | pmid = 24591852 }}</ref> |

|||

For some investigation teams this means that MS is a heterogeneous disease. Currently antibodies to [[lipids]] and [[peptides]] in sera, detected by [[microarrays]], can be used as markers of the pathological subtype given by brain biopsy.<ref name=Quintana08>{{cite journal |author=Quintana FJ, Farez MF, Viglietta V |title=Antigen microarrays identify unique serum autoantibody signatures in clinical and pathologic subtypes of multiple sclerosis |journal=Proc Natl Acad Sci USA |volume=105 |issue=48 |pages=18889–94 |date=December 2008 |pmid=19028871 |pmc=2596207 |doi=10.1073/pnas.0806310105 |url=http://www.pnas.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=19028871|author2=and others |displayauthors=1 |bibcode=2008PNAS..10518889Q |last3=Viglietta |last4=Iglesias |last5=Merbl |last6=Izquierdo |last7=Lucas |last8=Basso |last9=Khoury |last10=Lucchinetti |last11=Cohen |last12=Weiner }}</ref> |

|||

Other developments in this area is the finding that some lesions present [[Mitochondrion|mitochondrial]] defects that could distinguish types of lesions.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Mahad D, Ziabreva I, Lassmann H, Turnbull D. |title=Mitochondrial defects in acute multiple sclerosis lesions |journal= Brain |volume= 131|issue= Pt 7|pages= 1722–35|year=2008 |pmid=18515320 |doi=10.1093/brain/awn105 |pmc=2442422|last2=Ziabreva |last3=Lassmann |last4=Turnbull }}</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 11:08, 22 April 2016

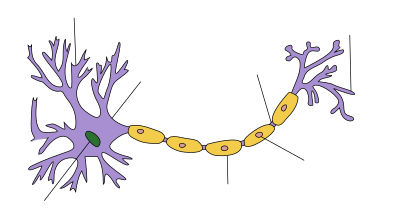

Multiple sclerosis is a putative autoimmune disorder in which activated immune cells invade the central nervous system and cause inflammation, neurodegeneration and tissue damage. There are three phenotypes: relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), characterized by periods of neurological worsening following by remissions; secondary-progressive MS (SPMS), in which there is gradual progression of neurological dysfunction with fewer or no relapses; and primary-progressive MS (MS), in which there is neurological deterioration from onset.

There are two phases for how an unknown underlying condition may cause damage in MS: First some MRI-abnormal areas with hidden damage appear in the brain and spine (NAWM, NAGM, DAWM). Second, there are leaks in the blood–brain barrier where immune cells infiltrate causing the known demyelination[1] and axon destruction.[2] Some clusters of activated microglia, transection of axons and myelin degeneration is present before the BBB breaks down and the immune attack begins[3][4][5]

Pathophysiology is a convergence of pathology with physiology. Pathology is the medical discipline that describes conditions typically observed during a disease state; whereas physiology is the biological discipline that describes processes or mechanisms operating within an organism. Referring to MS, the physiology refers to the different processes that lead to the development of the lesions and the pathology refers to the condition associated with the lesions.

Pathology

Multiple sclerosis can be pathologically defined as the presence of distributed scars (or sclerosis) in the central nervous system disseminated in time (DIT) and space (DIS).[6] These scleroses are the remainders of previous demyelinating lesions in the CNS white matter of a patient (encephalomyelitis) showing special characteristics, like for example confluent instead of perivenous demyelination.[7]

Multiple sclerosis differs from other idiopathic inflammatory demyelinating diseases in its confluent subpial cortical lesions, being a hallmark exclusively present in MS patients,[8]

Normally the WM lesions appear along to other kind of damage such as NAWM (normal appearing white matter) and grey matter lesions, but MS main findings take place inside the white matter, and lesions appear mainly in a peri-ventricular distribution (lesions clustered around the ventricles of the brain), but apart from the usually known white matter demyelination, also the cortex and deep gray matter (GM) nuclei are affected, together with diffuse injury of the normal-appearing white matter.[9] MS is active even during remission periods.[10] GM atrophy is independent of the MS lesions and is associated with physical disability, fatigue, and cognitive impairment in MS[11]

At least five characteristics are present in CNS tissues of MS patients: Inflammation beyond classical white matter lesions, intrathecal Ig production with oligoclonal bands, an environment fostering immune cell persistence, Follicle-like aggregates in the meninges and a disruption of the blood–brain barrier also outside of active lesions.[12] The scars that give the name to the condition are produced by the astrocyte cells healing old lesions.[13]

Physiology of MS

In multiple sclerosis there is an inflammatory condition together with a neurodegenerative condition. Clinical trials with humanized molecular antibodies have shown that the inflammation produces the relapses and the demyelination, and an independent neurodegeneration (axonal transection) produces the accumulative disability. Degeneration has been shown to advance even when inflammation and demyelination are detained.[14]

The lesion development process

Currently it is unknown what the primary cause of MS is. Current models can be divided into two groups: Inside-out and Outside-in. In the first ones, it is hypothesized that a problem in the CNS cells produces an immune response that destroys myelin and finally breaks the BBB. In the second models, an external factor produces BBB leaks, enters the CNS, and destroys myelin and axons.[15] Some authors claim that NAWM comes before the BBB breakdown [16] and some others point to adipsin as a factor of the breakdown.[17]

Whatever the underlying condition for MS is, some damage is triggered by a CSF unknown soluble factor, which is produced in meningeal areas and diffuses into the cortical parenchyma. It destroys myelin either directly or indirectly through microglia activation.[8]

Confluent subpial cortical lesions are the most specific finding for MS, being exclusively present in MS patients, though currently it can only be detected at autopsy.[8]

The lesions are driven mainly by T-cells. Nevertheless, recently it has been found that B-cells are also involved.[18]

Blood–brain barrier disruption

The blood–brain barrier (BBB) is a protective barrier that denies the entrance of foreign material into the nervous system. BBB disruption is the moment in which penetration of the barrier by lymphocytes occur and has been considered one of the early problems in MS lesions.[19]

The BBB is composed of endothelial cells which line the blood vessel walls of the central nervous system. Compared to normal endothelial cells, the cells lining the BBB are connected by occludin and claudin which form tight junctions in order to create a barrier to keep out larger molecules such as proteins. In order to pass through, molecules must be taken in by transport proteins or an alteration in the BBB permeability must occur, such as interactions with associated adaptor proteins like ZO-1, ZO-2 and ZO-3.[20] The BBB is compromised due to active recruitment of lymphocytes and monocytes and their migration across the barrier. Release of chemokines allow for the activation of adhesion molecules on the lymphocytes and monocytes, resulting in an interaction with the endothelial cells of the BBB which then activate the expression of matrix metalloproteinases to degrade the barrier.[20] This results in disruption of the BBB, causing an increase in barrier permeability due to the degradation of tight junctions which maintain barrier integrity. Inducing the formation of tight junctions can restore BBB integrity and reduces its permeability, which can be used to reduce the damage caused by lymphocyte and monocyte migration across the barrier as restored integrity would restrict their movement.[21]

After barrier breakdown symptoms may appear, such as swelling. Activation of macrophages and lymphocytes and their migration across the barrier may result in direct attacks on myelin sheaths within the central nervous system, leading to the characteristic demyelination event observed in MS.[22] After demyelination has occurred, the degraded myelin sheath components, such as myelin basic proteins and Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoproteins, are then used as identifying factors to facilitate further immune activity upon myelin sheaths. Further activation of cytokines is also induced by macrophage and lymphocyte activity, promoting inflammatory activity as well continued activation of proteins such as matrix metalloproteinases, which have detrimental effect on BBB integrity.[23]

Recently it has been found that BBB damage happens even in non-enhancing lesions.[24] MS has an important vascular component.[25]

Postmortem BBB study

Postmortem studies of the BBB, specially the vascular endotelium, show immunological abnormalities. Microvessels in periplaque areas coexpressed HLA-DR and VCAM-1, some others HLA-DR and urokinase plasminogen activator receptor, and others HLA-DR and ICAM-1.[26]

In vivo BBB study

This section may require copy editing. (September 2015) |

As lesions appear (using MRI) in "Normal-appearing white matter" (NAWM), the cause that finally triggers the BBB disruption is supposed to be there.[16] The damaged white matter is known as "Normal-appearing white matter" (NAWM) and is where lesions appear.[1] These lesions form in NAWM before blood–brain barrier breakdown.[27]

BBB can be broken centripetally or centrifugally, the first form being the most normal.[28] Several possible biochemical disrupters have been proposed. Some hypothesis about how the BBB is compromised revolve around the presence of different compounds in the blood that could interact with the vascular vessels only in the NAWM areas. The permeability of two cytokines, Interleukin 15 and LPS, could be involved in the BBB breakdown.[29] The BBB breakdown is responsible for monocyte infiltration and inflammation in the brain.[30] Monocyte migration and LFA-1-mediated attachment to brain microvascular endothelia is regulated by SDF-1alpha through Lyn kinase[31]

Using iron nanoparticles, involvement of macrophages in the BBB breakdown can be detected.[32] A special role is played by Matrix metalloproteinases. These are a group of proteases that increase T-cells permeability of the blood–brain barrier, specially in the case of MMP-9,[23] and are supposed to be related to the mechanism of action of interferons.[33]

Whether BBB dysfunction is the cause or the consequence of MS[34] is still disputed, because activated T-Cells can cross a healthy BBB when they express adhesion proteins.[35] Apart from that, activated T-Cells can cross a healthy BBB when they express adhesion proteins.[35] (Adhesion molecules could also play a role in inflammation[36]) In particular, one of these adhesion proteins involved is ALCAM (Activated Leukocyte Cell Adhesion Molecule, also called CD166), and is under study as therapeutic target.[37] Other protein also involved is CXCL12,[38] which is found also in brain biopsies of inflammatory elements,[39] and which could be related to the behavior of CXCL13 under methylprednisolone therapy.[40] Some molecular biochemical models for relapses have been proposed.[41]

Normally, gadolinium enhancement is used to show BBB disruption on MRIs.[42] Abnormal tight junctions are present in both SPMS and PPMS. They appear in active white matter lesions, and gray matter in SPMS. They persist in inactive lesions, particularly in PPMS.[43]

A deficiency of uric acid has been implicated in this process. Uric acid added in physiological concentrations (i.e. achieving normal concentrations) is therapeutic in MS by preventing the breakdown of the blood brain barrier through inactivation of peroxynitrite.[44] The low level of uric acid found in MS victims is manifestedly causative rather than a consequence of tissue damage in the white matter lesions,[45] but not in the grey matter lesions.[46] Besides, uric acid levels are lower during relapses.[47]

Normal-appearing tissues and their origin

Some areas that appear normal under normal MRI look abnormal under special MRI, like magnetisation transfer MTR-MRI. These are called Normal Appearing White Matter (NAWM) and Normal Appearing Grey Matter (NAGM).

The cause why the normal appearing areas appear in the brain is unknown. Historically, several theories about how this happens has been presented.

Old blood flow theories

Venous pathology has been associated with MS for more than a century. Pathologist Georg Eduard Rindfleisch noted in 1863 that the inflammation-associated lesions were distributed around veins.[48] Some other authors like Tracy Putnam[49] pointed to venous obstructions.

Some authors like Franz Schelling proposed a mechanical damage procedure based on violent blood reflux.[50] Later the focus moved to softer hemodynamic abnormalities, which were showing precede changes in sub-cortical gray matter[51] and in substantia nigra.[52] However, such reports of a "hemodynamic cause of MS" are not universal, and possibly not even common. At this time the evidence is largely anecdotal and some MS patients have no blood flow issues. Possibly vascular problems may be an aggravating factor, like many others in MS. Indeed, the research, by demonstrating patients with no hemodynamic problems actually prove that this is not the only cause of MS.

Endothelium theories

Other theories point to a possible primary endothelial dysfunction.[53] The importance of vascular misbehaviour in MS pathogenesis has also been independently confirmed by seven-tesla MRI.[54] It is reported that a number of studies have provided evidence of vascular occlusion in MS, which suggest the possibility of a primary vascular injury in MS lesions or at least that they are occasionally correlated.[55]

Some morphologically special medullar lesions (wedge-shaped) have also been linked to venous insufficiency.[56]

It has also been pointed out that some infectious agents with positive correlation to MS, specially Chlamydia pneumoniae, can cause problems in veins and arteries walls[57]

CCSVI

The term "chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency" was coined in 2008 by Paolo Zamboni, who described it in patients with multiple sclerosis. Instead of intracranial venous problems he described extracranial blockages, and he stated that the location of those obstructions seemed to influence the clinical course of the disease.[58] According to Zamboni, CCSVI had a high sensitivity and specificity differentiating healthy individuals from those with multiple sclerosis.[59] Zamboni's results were criticized as some of his studies were not blinded and they need to be verified by further studies.[58][59] As of 2010[update] the theory is considered at least defensible[60]

A more detailed evidence of a correlation between the place and type of venous malformations imaged and the reported symptoms of multiple sclerosis in the same patients was published in 2010.[61]

Haemodynamic problems have been found in the blood flow of MS patients using Doppler,[62] initially using transcranial color-coded duplex sonography (TCCS), pointing to a relationship with a vascular disease called chronic cerebro-spinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI).[63][64] In 2010 there were conflicting results when evaluating the relationship between MS and CCSVI.[65][66][67][68] but is important to note that positives have appeared among the blinded studies.

CSF flow theories

Other theories focus in the possible role of cerebrospinal fluid flow impairment.[69] This theory could be partially consistent with the previous one[70]

Currently a small trial with 8 participants has been performed[71]

CSF composition: Kir4.1 and Anoctamin-2

Whatever the underlying primary condition is, it is expected to be a soluble factor in the CSF,[8] maybe an unknown cytokine or ceramide, or a combination of them. Also B-cells and microglia could be involved[72][73]

It has been reported several times that CSF of some MS patients can damage myelin in culture[74][75][76][77][78] and mice[79][80] and ceramides have been recently brought into the stage.[81] Whatever the problem is, it produces apoptosis of neurons respecting astrocytes[82]

In 2012 it was reported that a subset of MS patients have a seropositive anti-Kir4.1 status,[83] which can represent up to a 47% of the MS cases, and the study has been reproduced by at least one other group.[84]

In 2016 a similar association was reported for anti-Anoctamin-2[85]

If the existence of any of these subsets of MS is confirmed, the situation would be similar to what happened for Devic Disease and Aquaporine-4. MS could be considered a heterogeneous condition or a new medical entity will be defined for these cases.

Primary neuro-degeneration theories

Some authors propose a primary neurodegenerative factor. Maybe the strongest argument supporting this theory comes from the comparison with NMO. Though autoimmune demyelination is strong, axons are preserved, showing that the standard model of a primary demyelination cannot be hold.[86] The theory of the trans-synaptic degeneration, is compatible with other models based in the CSF biochemistry.[87]

Others propose an oligodendrocyte stress as primary dysfunction, which activates microglia creating the NAWM areas[88] and others propose a yet-unknown intrinsic CNS trigger induces the microglial activation and clustering, which they point out could be again axonal injury or oligodendrocyte stress.[89]

Finally, other authors point to a cortical pathology which starts in the brain external layer (pial surface) and progresses extending into the brain inner layers[90]

MS biomarkers

Diagnosis of MS has always been made by clinical examination, supported by MRI or CSF tests. According with both the pure autoimmune hypothesis and the immune-mediated hypothesis,[91] researchers expect to find biomarkers able to yield a better diagnosis, and able to predict the response to the different available treatments.[92] As of 2014 no biomarker with perfect correlation has been found,[93] but some of them have shown a special behavior like an autoantibody against the potassium channel Kir4.1.[94] Biomarkers are expected to play an important role in the near future[95]

As of 2014, the only fully specific biomarkers found to date are four proteins in the CSF: CRTAC-IB (cartilage acidic protein), tetranectin (a plasminogen-binding protein), SPARC-like protein (a calcium binding cell signalling glycoprotein), and autotaxin-T (a phosphodiesterase)[96] Nevertheless, abnormal concentrations of non-specific proteins can also help in the diagnosis, like chitinases[97]

Biomarkers are also important for the expected response to therapy. Currently it has been proposed the protein SLC9A9 (gen Solute carrier family 9) as biomarker for the response to interferon beta[98]

Molecular biomarkers in blood

Blood serum of MS patients shows abnormalities. Endothelin-1 shows maybe the most striking discordance between patients and controls, being a 224% higher in patients than controls.[99]

Creatine and Uric acid levels are lower than normal, at least in women.[100] Ex vivo CD4(+) T cells isolated from the circulation show a wrong TIM-3 (Immunoregulation) behavior,[101] and relapses are associated with CD8(+) T Cells.[102] There is a set of differentially expressed genes between MS and healthy subjects in peripheral blood T cells from clinically active MS patients. There are also differences between acute relapses and complete remissions.[103] Platelets are known to have abnormal high levels.[104]

MS patients are also known to be CD46 defective, and this leads to Interleukin-10 (IL-10) deficiency, being this involved in the inflammatory reactions.[105] Levels of IL-2, IL-10, and GM-CSF are lower in MS females than normal. IL6 is higher instead. These findings do not apply to men.[106] This IL-10 interleukin could be related to the mechanism of action of methylprednisolone, together with CCL2. Interleukin IL-12 is also known to be associated with relapses, but this is unlikely to be related to the response to steroids[107]

Kallikreins are found in serum and are associated with secondary progressive stage.[108] Related to this, it has been found that B1-receptors, part of the kallikrein-kinin-system, are involved in the BBB breakdown[109][110]

There is evidence of Apoptosis-related molecules in blood and they are related to disease activity.[111] B cells in CSF appear, and they correlate with early brain inflammation.[112] There is also an overexpression of IgG-free kappa light chain protein in both CIS and RR-MS patients, compared with control subjects, together with an increased expression of an isoforms of apolipoprotein E in RR-MS.[113] Expression of some specific proteins in circulating CD4+ T cells is a risk factor for conversion from CIS to clinically defined multiple sclerosis.[114]

Recently, unique autoantibody patterns that distinguish RRMS, secondary progressive (SPMS), and primary progressive (PPMS) have been found, based on up- and down-regulation of CNS antigens,[115] tested by microarrays. In particular, RRMS is characterized by autoantibodies to heat shock proteins that were not observed in PPMS or SPMS. These antibodies patterns can be used to monitor disease progression.[116][117]

Finally, a promising biomarker under study is an antibody against the potassium channel protein KIR4.1.[94] This biomarker has been reported to be present in around a half of MS patients, but in nearly none of the controls.

MS types by genetics

By RNA profile

Also in blood serum can be found the RNA type of the MS patient. Two types have been proposed classifying the patients as MSA or MSB, allegedly predicting future inflammatory events.[118]

By transcription factor

The autoimmune disease-associated transcription factors EOMES and TBX21 are dysregulated in multiple sclerosis and define a molecular subtype of disease.[119] The importance of this discovery is that the expression of these genes appears in blood and can be measured by a simple blood analysis.

In blood vessels tissue

Endothelial dysfunction has been reported in MS[120] and could be used as biomarker via biopsia. Blood circulation is slower in MS patients and can be measured using contrast[121] or by MRI[122]

Interleukin-12p40 has been reported to separate RRMS and CIS from other neurological diseases[123]

In Cerebrospinal Fluid

It has been known for quite some time that glutamate is present at higher levels in CSF during relapses[124] and to MS patients before relapses compared to healthy subjects. This observation has been linked to the activity of the infiltrating leukocytes and activated microglia, and to the damage to the axons[125] and to the oligodendrocytes damage, supposed to be the main cleaning agents for glutamate[126]

Also a specific MS protein has been found in CSF, chromogranin A, possibly related to axonal degeneration. It appears together with clusterin and complement C3, markers of complement-mediated inflammatory reactions.[127] Also Fibroblast growth factor-2 appear higher at CSF.[128]

CSF also shows oligoclonal bands (OCB) in the majority (around 95%) of the patients. Several studies have reported differences between patients with and without OCB with regard to clinical parameters such as age, gender, disease duration, clinical severity and several MRI characteristics, together with a varying lesion load.[129] Free kappa chains in CSF are documented and have been proposed as a marker for MS evolution[130]

Varicella-zoster virus particles have been found in CSF of patients during relapses, but this particles are virtually absent during remissions.[131] Plasma Cells in the cerebrospinal fluid of MS patients could also be used for diagnosis, because they have been found to produce myelin-specific antibodies.[132] As of 2011, a recently discovered myelin protein TPPP/p25, has been found in CSF of MS patients[133]

A study found that quantification of several immune cell subsets, both in blood and CSF, showed differences between intrathecal (from the spine) and systemic immunity, and between CSF cell subtypes in the inflammatory and noninflammatory groups (basically RRMS/SPMS compared to PPMS). This showed that some patients diagnosed with PPMS shared an inflammatory profile with RRMS and SPMS, while others didn't.[134]

Other study found using a proteomic analysis of the CSF that the peak intensity of the signals corresponding to Secretogranin II and Protein 7B2 were significantly upregulated in RRMS patients compared to PrMS (p<0.05), whereas the signals of Fibrinogen and Fibrinopeptide A were significantly downregulated in CIS compared to PrMS patients[135]

As of 2014 it is considered that the CSF signature of MS is a combination of cytokines[136] CSF lactate has been found to correlate to disease progression[137]

Micro-RNA as biomarker

Micro-RNA are non-coding RNA of around 22 nucleotides in length. They are present in blood and in CSF. Several studies have found specific micro-RNA signatures for MS[138]

Biomarkers in brain cells and biopsies

Abnormal sodium distribution has been reported in living MS brains. In the early-stage RRMS patients, sodium MRI revealed abnormally high concentrations of sodium in brainstem, cerebellum and temporal pole. In the advanced-stage RRMS patients, abnormally high sodium accumulation was widespread throughout the whole brain, including normal appearing brain tissue.[139] It is currently unknown whether post-mortem brains are consistent with this observation.

The pre-active lesions are clusters of microglia driven by the HspB5 protein, thought to be produced by stressed oligodendrocytes. The presence of HspB5 in biopsies can be a marker for lesion development.[4]

Biomarkers by MRI

Recently SWI adjusted magnetic resonance has given results close to 100% specificity and sensitivity respect McDonalds CDMS status[140] and Magnetization transfer MRI has shown that NAWM evolves during the disease reducing its magnetization transfer coeficient[141]

Biomarkers for the clinical courses

Currently it is possible to distinguish between the three main clinical coursesusing a combination of four blood protein tests with an accuracy around 80% [142]

Currently the best predictor for clinical multiple sclerosis is the number of T2 lesions visualized by MRI during the CIS, but it has been proposed to complement it with MRI measures of BBB permeability[143] It is normal to evaluate diagnostic criteria against the "time to conversion to definite".

Subgroups by molecular biomarkers

Differences have been found between the proteines expressed by patients and healthy subjects, and between attacks and remissions. Using DNA microarray technology groups of molecular biomarkers can be established.[144] For example, it is known that Anti-lipid oligoclonal IgM bands (OCMB) distinguish MS patients with early aggressive course and that these patients show a favourable response to immunomodulatory treatment.[145]

It seems that Fas and MIF are candidate biomarkers of progressive neurodegeneration. Upregulated levels of sFas (soluble form of Fas molecule) were found in MS patients with hypotense lesions with progressive neurodegeneration, and also levels of MIF appeared to be higher in progressive than in non-progressing patients. Serum TNF-α and CCL2 seem to reflect the presence of inflammatory responses in primary progressive MS.[146]

As previously reported, there is an antibody against the potassium channel protein KIR4.1[94] which is present in around a half of MS patients, but in nearly none of the controls, pointing towards an heterogeneous etiology in MS. The same happens with B-Cells[147]

Biomarkers for response to therapy

Response to therapy is heterogeneous in MS. Serum cytokine profiles have been proposed as biomarkers for response to Betaseron[148] and the same was proposed to MxA mRNA.[149]

Demyelination patters

Demyelination patterns

Four different damage patterns have been identified in patient's brain tissues. The original report suggests that there may be several types of MS with different immune causes, and that MS may be a family of several diseases. Though originally was required a biopsy to classify the lesions of a patient, since 2012 it is possible to classify them by a blood test[150] looking for antibodies against 7 lipids, three of which are cholesterol derivatives[151]

It is believed that they may correlate with differences in disease type and prognosis, and perhaps with different responses to treatment. In any case, understanding lesion patterns can provide information about differences in disease between individuals and enable doctors to make more accurate treatment decisions

According to one of the researchers involved in the original research "Two patterns (I and II) showed close similarities to T-cell-mediated or T-cell plus antibody-mediated autoimmune encephalomyelitis, respectively. The other patterns (III and IV) were highly suggestive of a primary oligodendrocyte dystrophy, reminiscent of virus- or toxin-induced demyelination rather than autoimmunity."

The four identified patterns are:[152]

- Pattern I

- The scar presents T-cells and macrophages around blood vessels, with preservation of oligodendrocytes, but no signs of complement system activation.[153]

- Pattern II

- The scar presents T-cells and macrophages around blood vessels, with preservation of oligodendrocytes, as before, but also signs of complement system activation can be found.[154] This pattern has been considered similar to damage seen in NMO, though AQP4 damage does not appear in pattern II MS lesions[155] Nevertheless, pattern II has been reported to respond to plasmapheresis,[156] which points to something pathogenic into the blood serum.

- The complement system infiltration in these cases convert this pattern into a candidate for research into autoimmune connections like anti-Kir4.1, [83] anti- Anoctamin-2[157] or anti-MOG mediated MS[158] About the last possibility, research has found antiMOG antibodies in some pattern-II MS patients.[159]

- Pattern II pathogenic T cells have already been cloned and prepared for further studies.[160][161] The functional characterization shows that T cells releasing Th2 cytokines and helping B cells dominate the T-cell infiltrate in pattern II brain lesions.[160]

- Pattern III

- The scars are diffuse with inflammation, distal oligodendrogliopathy and microglial activation. There is also loss of myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG). The scars do not surround the blood vessels, and in fact, a rim of preserved myelin appears around the vessels. There is evidence of partial remyelinization and oligodendrocyte apoptosis. For some researchers this pattern is an early stage of the evolution of the others.[162] For others, it represents ischaemia-like injury with a remarkable availability of a specific biomarker in CSF[163][164]

- Pattern IV

- The scar presents sharp borders and oligodendrocyte degeneration, with a rim of normal appearing white matter. There is a lack of oligodendrocytes in the center of the scar. There is no complement activation or MAG loss.

These differences are noticeable only in early lesions[165] and the heterogeneity was controversial during some time because some research groups thought that these four patterns could be consequence of the age of the lesions.[166] Nevertheless, after some debate among research groups, the four patterns model is accepted and the exceptional case found by Prineas has been classified as NMO[167][168]

For some investigation teams this means that MS is a heterogeneous disease. Currently antibodies to lipids and peptides in sera, detected by microarrays, can be used as markers of the pathological subtype given by brain biopsy.[116]

Other developments in this area is the finding that some lesions present mitochondrial defects that could distinguish types of lesions.[169]

See also

References

- ^ a b Goodkin DE, Rooney WD, Sloan R; et al. (December 1998). "A serial study of new MS lesions and the white matter from which they arise". Neurology. 51 (6): 1689–97. doi:10.1212/wnl.51.6.1689. PMID 9855524.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tallantyre EC1, Bø L, Al-Rawashdeh O, Owens T, Polman CH, Lowe JS, Evangelou N. "Clinico-pathological evidence that axonal loss underlies disability in progressive multiple sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2010 May;119(5):601-15. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0618-9. Epub 2009 Dec 5.

- ^ van der Valk P, Amor S; Amor (June 2009). "Preactive lesions in multiple sclerosis". Current Opinion in Neurology. 22 (3): 207–13. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e32832b4c76. PMID 19417567.

- ^ a b Bsibsi M, Holtman IR, Gerritsen WH, Eggen BJ, Boddeke E, van der Valk P, van Noort JM, Amor S. Alpha-B-Crystallin Induces an Immune-Regulatory and Antiviral Microglial Response in Preactive Multiple Sclerosis Lesions, J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013 Sep 13, doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182a776bf PMID 24042199

- ^ Ontaneda; et al. (Nov 2014). "Identifying the Start of Multiple Sclerosis Injury: A Serial DTI Study". J Neuroimaging. 24 (6): 569–76. doi:10.1111/jon.12082.

- ^ Dutta R, Trapp BD (Jun 2006). "Pathology and definition of multiple sclerosis". Rev Prat. 56 (12): 1293–8.

- ^ Young Nathan P., Weinshenker Brian G., Parisi Joseph E., Scheithauer B., Giannini C., Roemer Shanu F., Thomsen Kristine M., Mandrekar Jayawant N., Erickson Bradley J., Lucchinetti Claudia F. (2010). "Perivenous demyelination: association with clinically defined acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and comparison with pathologically confirmed multiple sclerosis". Brain. 133: 333–348. doi:10.1093/brain/awp321.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Lassmann Hans (2014). "Multiple sclerosis: Lessons from molecular neuropathology". Experimental Neurology. 262: 2–7. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.12.003.

- ^ Lassmann H, Brück W, Lucchinetti CF; Brück; Lucchinetti (April 2007). "The immunopathology of multiple sclerosis: an overview". Brain Pathol. 17 (2): 210–8. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00064.x. PMID 17388952.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kirov I, Patil V, Babb J, Rusinek H, Herbert J, Gonen O; Patil; Babb; Rusinek; Herbert; Gonen (June 2009). "MR Spectroscopy Indicates Diffuse Multiple Sclerosis Activity During Remission". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 80 (12): 1330–6. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2009.176263. PMC 2900785. PMID 19546105.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pirko I, Lucchinetti CF, Sriram S, Bakshi R; Lucchinetti; Sriram; Bakshi (February 2007). "Gray matter involvement in multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 68 (9): 634–42. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000250267.85698.7a. PMID 17325269.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Meinl E, Krumbholz M, Derfuss T, Dewitt D,; Krumbholz; Derfuss; Junker; Hohlfeld (November 2008). "Compartmentalization of inflammation in the CNS: A major mechanism driving progressive multiple sclerosis". J Neurol Sci. 274 (1–2): 42–4. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2008.06.032. PMID 18715571.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brosnan C. F., Raine C. S. (2013). "The astrocyte in multiple sclerosis revisited". Glia. 61: 453–465. doi:10.1002/glia.22443.

- ^ Alasdair J. Cole et al. Monoclonal Antibody Treatment Exposes Three Mechanisms Underlying the Clinical Course of Multiple Sclerosis, Ann Neurol 1999;46:296 –304 [1]

- ^ Ikuo Tsunoda, Robert S. Fujinami, Inside-Out versus Outside-In models for virus induced demyelination: axonal damage triggering demyelination, Springer Seminars in Immunopathology, November 2002, Volume 24, Issue 2, pp 105-125

- ^ a b Werring DJ, Brassat D, Droogan AG; et al. (August 2000). "The pathogenesis of lesions and normal-appearing white matter changes in multiple sclerosis: a serial diffusion MRI study". Brain. 123 (8): 1667–76. doi:10.1093/brain/123.8.1667. PMID 10908196.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schmid A et al. Quantification and regulation of adipsin in human cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2015 Jul 17. doi: 10.1111/cen.12856.PMID 26186410

- ^ Ireland SJ, Guzman AA, Frohman EM, Monson NL, B cells from relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis patients support neuro-antigen-specific Th17 responses. J Neuroimmunol. 2016 Feb 15;291:46-53. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.11.022. Epub 2015 Nov 26.

- ^ Alireza Minagar and J Steven Alexander, Blood–brain barrier disruption in multiple sclerosis [2]

- ^ a b Correale, Jorge; Andrés Villa (24 July 2006). "The blood–brain-barrier in multiple sclerosis: Functional roles and therapeutic targeting". Autoimmunity. 40 (2): 148–160. doi:10.1080/08916930601183522.

- ^ Cristante, Enrico; Simon McArthur, Claudio Mauro, Elisa Maggiolo, Ignacio A. Romero, Marzena Wylezinska-Arridge, Pierre O. Couraud, Jordi Lopez-Tremoleda, Helen C. Christian, Babette B. Weksler, Andrea Malaspina, Egle Solito; Mauro, C.; Maggioli, E.; Romero, I. A.; Wylezinska-Arridge, M.; Couraud, P. O.; Lopez-Tremoleda, J.; Christian, H. C.; Weksler, B. B.; Malaspina, A.; Solito, E. (15 January 2013). "Identification of an essential endogenous regulator of blood–brain barrier integrity, and its pathological and therapeutic implications". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (3): 832–841. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110..832C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1209362110.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Prat, Elisabetta; Roland Martin (March–April 2002). "The immunopathogenesis of multiple sclerosis". Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 39 (2): 187.

- ^ a b Gray E, Thomas TL, Betmouni S, Scolding N, Love S; Thomas; Betmouni; Scolding; Love (September 2008). "Elevated matrix metalloproteinase-9 and degradation of perineuronal nets in cerebrocortical multiple sclerosis plaques". J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 67 (9): 888–99. doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e318183d003. PMID 18716555.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Soon D, Tozer DJ, Altmann DR, Tofts PS, Miller DH; Tozer; Altmann; Tofts; Miller (2007). "Quantification of subtle blood–brain barrier disruption in non-enhancing lesions in multiple sclerosis: a study of disease and lesion subtypes". Multiple Sclerosis. 13 (7): 884–94. doi:10.1177/1352458507076970. PMID 17468443.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Minagar A, Jy W, Jimenez JJ, Alexander JS; Jy; Jimenez; Alexander (2006). "Multiple sclerosis as a vascular disease". Neurol. Res. 28 (3): 230–5. doi:10.1179/016164106X98080. PMID 16687046.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Washington R, Burton J, Todd RF 3rd, Newman W, Dragovic L, Dore-Duffy P (Jan 1994). "Expression of immunologically relevant endothelial cell activation antigens on isolated central nervous system microvessels from patients with multiple sclerosis". Ann. Neurol. 35 (1): 89–97. doi:10.1002/ana.410350114. PMID 7506877.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Allen; McQuaid, S; Mirakhur, M; Nevin, G (2001). "Pathological abnormalities in the normal-appearing white matter in multiple sclerosis". Neurol Sci. 22 (2): 141–4. doi:10.1007/s100720170012. PMID 11603615.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Shinohara RT, Crainiceanu CM, Caffo BS, Gaitán MI, Reich DS; Crainiceanu; Caffo; Gaitán; Reich (May 2011). "Population-Wide Principal Component-Based Quantification of Blood-Brain-Barrier Dynamics in Multiple Sclerosis". NeuroImage. 57 (4): 1430–46. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.038. PMC 3138825. PMID 21635955.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pan W, Hsuchou H, Yu C, Kastin AJ; Hsuchou; Yu; Kastin (2008). "Permeation of blood-borne IL15 across the blood–brain barrier and the effect of LPS". J. Neurochem. 106 (1): 313–9. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05390.x. PMC 3939609. PMID 18384647.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Reijerkerk A, Kooij G, van der Pol SM, Leyen T, van Het Hof B, Couraud PO, Vivien D, Dijkstra CD, de Vries HE.; Kooij; Van Der Pol; Leyen; Van Het Hof; Couraud; Vivien; Dijkstra; De Vries (2008). "Tissue-type plasminogen activator is a regulator of monocyte diapedesis through the brain endothelial barrier". Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950). 181 (5): 3567–74. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3567. PMID 18714030.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Malik M, Chen YY, Kienzle MF, Tomkowicz BE, Collman RG, Ptasznik A; Chen; Kienzle; Tomkowicz; Collman; Ptasznik (October 2008). "Monocyte migration and LFA-1 mediated attachment to brain microvascular endothelia is regulated by SDF-1α through Lyn kinase". Journal of Immunology. 181 (7): 4632–7. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4632. PMC 2721474. PMID 18802065.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Petry KG, Boiziau C, Dousset V, Brochet B; Boiziau; Dousset; Brochet (2007). "Magnetic resonance imaging of human brain macrophage infiltration". Neurotherapeutics : the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics. 4 (3): 434–42. doi:10.1016/j.nurt.2007.05.005. PMID 17599709.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boz C, Ozmenoglu M, Velioglu S; et al. (February 2006). "Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase (TIMP-1) in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis treated with interferon beta". Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 108 (2): 124–8. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2005.01.005. PMID 16412833.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Waubant E (2006). "Biomarkers indicative of blood–brain barrier disruption in multiple sclerosis". Dis. Markers. 22 (4): 235–44. doi:10.1155/2006/709869. PMC 3850823. PMID 17124345.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Multiple Sclerosis at eMedicine

- ^ Elovaara I, Ukkonen M, Leppäkynnäs M; et al. (April 2000). "Adhesion molecules in multiple sclerosis: relation to subtypes of disease and methylprednisolone therapy". Arch. Neurol. 57 (4): 546–51. doi:10.1001/archneur.57.4.546. PMID 10768630.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Alexandre Prat, Nicole Beaulieu, Sylvain-Jacques Desjardins, New Therapeutic Target For Treatment Of Multiple Sclerosis, Jan. 2008

- ^ McCandless EE, Piccio L, Woerner BM; et al. (March 2008). "Pathological Expression of CXCL12 at the Blood-Brain Barrier Correlates with Severity of Multiple Sclerosis". Am J Pathol. 172 (3): 799–808. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2008.070918. PMC 2258272. PMID 18276777.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moll NM, Cossoy MB, Fisher E; et al. (January 2009). "Imaging correlates of leukocyte accumulation and CXCR4/CXCR12 in multiple sclerosis". Arch. Neurol. 66 (1): 44–53. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2008.512. PMC 2792736. PMID 19139298.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Michałowska-Wender G, Losy J, Biernacka-Łukanty J, Wender M; Losy; Biernacka-Łukanty; Wender (2008). "Impact of methylprednisolone treatment on the expression of macrophage inflammatory protein 3alpha and B lymphocyte chemoattractant in serum of multiple sclerosis patients" (PDF). Pharmacol Rep. 60 (4): 549–54. PMID 18799824.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Steinman L (May 2009). "A molecular trio in relapse and remission in multiple sclerosis". Nature Reviews Immunology. 9 (6): 440–7. doi:10.1038/nri2548. PMID 19444308.

- ^ Waubant E (2006). "Biomarkers indicative of blood–brain barrier disruption in multiple sclerosis". Disease Markers. 22 (4): 235–44. doi:10.1155/2006/709869. PMC 3850823. PMID 17124345.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Leech S, Kirk J, Plumb J, McQuaid S; Kirk; Plumb; McQuaid (2007). "Persistent endothelial abnormalities and blood–brain barrier leak in primary and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis". Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 33 (1): 86–98. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2990.2006.00781.x. PMID 17239011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kean R, Spitsin S, Mikheeva T, Scott G, Hooper D; Spitsin; Mikheeva; Scott; Hooper (2000). "The peroxynitrite scavenger uric acid prevents inflammatory cell invasion into the central nervous system in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis through maintenance of blood-central nervous system barrier integrity". Journal of Immunology. 165 (11): 6511–8. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6511. PMID 11086092.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rentzos M, Nikolaou C, Anagnostouli M, Rombos A, Tsakanikas K, Economou M, Dimitrakopoulos A, Karouli M, Vassilopoulos D; Nikolaou; Anagnostouli; Rombos; Tsakanikas; Economou; Dimitrakopoulos; Karouli; Vassilopoulos (2006). "Serum uric acid and multiple sclerosis". Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 108 (6): 527–31. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2005.08.004. PMID 16202511.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ van Horssen J, Brink BP, de Vries HE, van der Valk P, Bø L; Brink; De Vries; Van Der Valk; Bø (April 2007). "The blood–brain barrier in cortical multiple sclerosis lesions". J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 66 (4): 321–8. doi:10.1097/nen.0b013e318040b2de. PMID 17413323.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Guerrero AL, Martín-Polo J, Laherrán E; et al. (April 2008). "Variation of serum uric acid levels in multiple sclerosis during relapses and immunomodulatory treatment". Eur J Neurol. 15 (4): 394–7. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02087.x. PMID 18312403.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lassmann H (July 2005). "Multiple sclerosis pathology: evolution of pathogenetic concepts". Brain Pathology. 15 (3): 217–22. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2005.tb00523.x. PMID 16196388.[verification needed]

- ^ Putnam, T.J. (1937) Evidence of vascular occlusion in multiple sclerosis

- ^ Schelling, F (October 1986). "Damaging venous reflux into the skull or spine: relevance to multiple sclerosis". Medical Hypotheses. 21 (2): 141–8. doi:10.1016/0306-9877(86)90003-4. PMID 3641027.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Varga AW, Johnson G, Babb JS, Herbert J, Grossman RI, Inglese M; Johnson; Babb; Herbert; Grossman; Inglese (July 2009). "White Matter Hemodynamic Abnormalities precede Sub-cortical Gray Matter Changes in Multiple Sclerosis". J. Neurol. Sci. 282 (1–2): 28–33. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2008.12.036. PMC 2737614. PMID 19181347.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Walter U, Wagner S, Horowski S, Benecke R, Zettl UK; Wagner; Horowski; Benecke; Zettl (September 2009). "Transcranial brain sonography findings predict disease progression in multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 73 (13): 1010–7. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b8a9f8. PMID 19657105.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Leech S, Kirk J, Plumb J, McQuaid S; Kirk; Plumb; McQuaid (February 2007). "Persistent endothelial abnormalities and blood–brain barrier leak in primary and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis". Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 33 (1): 86–98. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2990.2006.00781.x. PMID 17239011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ge Y, Zohrabian VM, Grossman RI.; Zohrabian; Grossman (2008). "7T MRI: New Vision of Microvascular Abnormalities in Multiple Sclerosis". Archives of neurology. 65 (6): 812–6. doi:10.1001/archneur.65.6.812. PMC 2579786. PMID 18541803.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ M. Filippi, G. Comi (2004). "Normal-appearing White and Grey Matter Damage in Multiple Sclerosis. Book review". AJRN. 27 (4): 945–946.

- ^ Qiu, W; Raven, S; Wu, JS; Carroll, WM; Mastaglia, FL; Kermode, AG (March 2010). "Wedge-shaped medullary lesions in multiple sclerosis". Journal of the neurological sciences. 290 (1–2): 190–3. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2009.12.017. PMID 20056253.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ J. Gutiérrez, J. Linares-Palomino, C. Lopez-Espada, M. Rodríguez, E. Ros, G. Piédrola and M. del C. Maroto, "Chlamydia pneumoniae DNA in the Arterial Wall of Patients with Peripheral Vascular Disease, Infection Volume 29, Number 4 (2001), 196-200 doi:10.1007/s15010-001-1180-0

- ^ a b Zamboni P, Galeotti R, Menegatti E; et al. (April 2009). "Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency in patients with multiple sclerosis". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 80 (4): 392–9. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2008.157164. PMC 2647682. PMID 19060024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Khan O, Filippi M, Freedman MS; et al. (March 2010). "Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency and multiple sclerosis". Annals of Neurology. 67 (3): 286–90. doi:10.1002/ana.22001. PMID 20373339.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bryce Weir (2010). "MS, A vascular ethiology?" (PDF). Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 37: 745–757.

- ^ Bartolomei I.; et al. (April 2010). "Haemodynamic patterns in chronic cereblrospinal venous insufficiency in multiple sclerosis. Correlation of symptoms at onset and clinical course". Int Angiol. 29 (2): 183–8. PMID 20351667.

- ^ Zamboni P, Menegatti E, Bartolomei I; et al. (November 2007). "Intracranial venous haemodynamics in multiple sclerosis". Curr Neurovasc Res. 4 (4): 252–8. doi:10.2174/156720207782446298. PMID 18045150.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zamboni P, Galeotti R, Menegatti E; et al. (April 2009). "Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency in patients with multiple sclerosis". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 80 (4): 392–9. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2008.157164. PMC 2647682. PMID 19060024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lee AB, Laredo J, Neville R; Laredo; Neville (April 2010). "Embryological background of truncular venous malformation in the extracranial venous pathways as the cause of chronic cerebro spinal venous insufficiency" (PDF). Int Angiol. 29 (2): 95–108. PMID 20351665.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Al-Omari MH, Rousan LA; Rousan (April 2010). "Internal jugular vein morphology and hemodynamics in patients with multiple sclerosis". Int Angiol. 29 (2): 115–20. PMID 20351667.

- ^ Krogias C, Schröder A, Wiendl H, Hohlfeld R, Gold R; Schröder; Wiendl; Hohlfeld; Gold (April 2010). "["Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency" and multiple sclerosis : Critical analysis and first observation in an unselected cohort of MS patients.]". Nervenarzt. 81 (6): 740–6. doi:10.1007/s00115-010-2972-1. PMID 20386873.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Doepp F, Paul F, Valdueza JM, Schmierer K, Schreiber SJ; Paul; Valdueza; Schmierer; Schreiber (August 2010). "No cerebrocervical venous congestion in patients with multiple sclerosis". Annals of Neurology. 68 (2): 173–83. doi:10.1002/ana.22085. PMID 20695010.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sundström, P.; Wåhlin, A.; Ambarki, K.; Birgander, R.; Eklund, A.; Malm, J. (2010). "Venous and cerebrospinal fluid flow in multiple sclerosis: A case-control study". Annals of Neurology. 68 (2): 255–259. doi:10.1002/ana.22132. PMID 20695018.

- ^ Damadian RV, Chu D. The possible role of cranio-cervical trauma and abnormal CSF hydrodynamics in the genesis of multiple sclerosis, 2011, [3]

- ^ Zamboni; et al. (2010). "CSF dynamics and brain volume in multiple sclerosis are associated with extracranial venous flow anomalies". Int Angiol. 29: 140–8. PMID 20351670.

- ^ Raymond V. Damadian and David Chu, The Possible Role of Cranio-Cervical Trauma and Abnormal CSF Hydrodynamics in the Genesis of Multiple Sclerosis [4][5][6]

- ^ Robert P. Lisak et al. 2012 Secretory products of multiple sclerosis B cells are cytotoxic to oligodendroglia in vitro, Journal of Neuroimmunology, Volume 246, Issues 1–2, Pages 85–95 doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.02.015

- ^ Ilana Katz Sand et al. CSF from MS Patients Induces Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Unmyelinated Neuronal Cultures, Neurology February 12, 2013; 80(Meeting Abstracts 1): P05.179

- ^ Alcázar A1 Regidor I, Masjuan J, Salinas M, Alvarez-Cermeño JC (Apr 2000). "Axonal damage induced by cerebrospinal fluid from patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis". J Neuroimmunol. 104 (1): 58–67. doi:10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00225-8.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Alvarez-Cermeño JC, Cid C, Regidor I, Masjuan J, Salinas-Aracil M, Alcázar-González A (2002). "The effect of cerebrospinal fluid on neurone culture: implications in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis". Rev Neurol. 35 (10): 994–7.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cid C1 Alvarez-Cermeño JC, Camafeita E, Salinas M, Alcázar A (Feb 2004). "Antibodies reactive to heat shock protein 90 induce oligodendrocyte precursor cell death in culture. Implications for demyelination in multiple sclerosis". FASEB J. 18 (2): 409–11. doi:10.1096/fj.03-0606fje.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Tiwari-Woodruff SK, Myers LW, Bronstein JM. "Cerebrospinal fluid immunoglobulin G promotes oligodendrocyte progenitor cell migration. ;;J Neurosci Res.;; 2004 Aug 1;77(3):363-6.

- ^ Cristofanilli M, Cymring B, Lu A, Rosenthal H, Sadiq SA (Oct 2013). "Cerebrospinal fluid derived from progressive multiple sclerosis patients promotes neuronal and oligodendroglial differentiation of human neural precursor cells in vitro". Neuroscience. 250: 614–21. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.07.022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cristofanilli M, Rosenthal H, Cymring B, Gratch D, Pagano B, Xie B, Sadiq SA, "Progressive multiple sclerosis cerebrospinal fluid induces inflammatory demyelination, axonal loss, and astrogliosis in mice, Exp Neurol. 2014; doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.07.020 PMID 25111532

- ^ Saeki Y, Mima T, Sakoda S, Fujimura H, Arita N, Nomura T, Kishimoto T (1992). "Transfer of multiple sclerosis into severe combined immunodeficiency mice by mononuclear cells from cerebrospinal fluid of the patients". PNAS. 89: 13. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.13.6157.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vidaurre OG, et al. (Aug 2014). "Cerebrospinal fluid ceramides from patients with multiple sclerosis impair neuronal bioenergetics". Brain. 137 (8): 2271–86. doi:10.1093/brain/awu139.

- ^ Burgal , Mathur (Jul 2014). "Molecular Shots". Ann Neurosci. 21 (3): 123. doi:10.5214/ans.0972.7531.210311.

- ^ a b Srivastava R, et al. (Jul 2012). "Potassium channel KIR4.1 as an immune target in multiple sclerosis". N Engl J Med. 367 (2): 115–23. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110740. PMID 22784115. Cite error: The named reference "ReferenceA" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Raphael Schneider "Autoantibodies to Potassium Channel KIR4.1 in Multiple Sclerosis doi: 10.3389/fneur.2013.00125 PMID 24032025

- ^ Burcu Ayoglua et al. Anoctamin 2 identified as an autoimmune target in multiple sclerosis. PNAS 2016 ; published ahead of print February 9, 2016, doi:10.1073/pnas.1518553113

- ^ Matthews Lucy; et al. "Imaging Surrogates of Disease Activity in Neuromyelitis Optica Allow Distinction from Multiple Sclerosis". PLOS ONE. 10: e0137715. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0137715.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Alcázar A.; et al. (2000). "Axonal damage induced by cerebrospinal fluid from patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neuroimmunology. 104 (1): 58–67. doi:10.1016/S0165-5728(99)00225-8.

- ^ Peferoen, L., D. Vogel, Marjolein Breur, Wouter Gerritsen, C. Dijkstra, and S. Amor. "Do stressed oligodendrocytes trigger microglia activation in pre-active MS lesions?." In GLIA, vol. 61, pp. S164-S164. 111 RIVER ST, HOBOKEN 07030-5774, NJ USA: WILEY-BLACKWELL, 2013.

- ^ van Horssen Jack; et al. "Clusters of activated microglia in normal-appearing white matter show signs of innate immune activation". Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2012 (9): 156.

- ^ Mainero C, et al. (2015). "A gradient in cortical pathology in multiple sclerosis by in vivo quantitative 7 T imaging". Brain. 138: 932–45. doi:10.1093/brain/awv011. PMID 25681411.

- ^ Wootla B, Eriguchi M, Rodriguez M (2012). "Is multiple sclerosis an autoimmune disease?". Autoimmune Dis. 2012: 969657. doi:10.1155/2012/969657.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Buck Dorothea, Hemmer Bernhard (2014). "Biomarkers of treatment response in multiple sclerosis". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 14 (2): 165–172. doi:10.1586/14737175.2014.874289.

- ^ Comabella Manuel, Montalban Xavier (2014). "Body fluid biomarkers in multiple sclerosis". The Lancet Neurology. 13 (1): 113–126. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70233-3.

- ^ a b c Srivastava Rajneesh; et al. (2012). "Potassium Channel KIR4.1 as an Immune Target in Multiple Sclerosis". New England Journal of Medicine. 367: 115–123. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110740. PMID 22784115.

- ^ Katsavos Serafeim, Anagnostouli Maria. "Biomarkers in Multiple Sclerosis: An Up-to-Date Overview". Multiple Sclerosis International. 2013: 340508. doi:10.1155/2013/340508.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Proteomic analysis of multiple sclerosis cerebrospinal fluid". Mult Scler. 10: 245–60. Jun 2004. doi:10.1191/1352458504ms1023oa. PMID 15222687.

- ^ Hinsinger G, et al. (2015). "Chitinase 3-like proteins as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of multiple sclerosis". Mult Scler. doi:10.1177/1352458514561906.

- ^ Esposito F et al. A pharmacogenetic study implicates SLC9A9 in multiple sclerosis disease activity. Ann Neurol. 2015; doi: 10.1002/ana.24429. PMID 25914168

- ^ Haufschild T, Shaw SG, Kesselring J, Flammer J (Mar 2001). "Increased endothelin-1 plasma levels in patients with multiple sclerosis". J Neuroophthalmol. 21 (1): 37–8. doi:10.1097/00041327-200103000-00011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kanabrocki EL, Ryan MD, Hermida RC; et al. (2008). "Uric acid and renal function in multiple sclerosis". Clin Ter. 159 (1): 35–40. PMID 18399261.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yang L, Anderson DE, Kuchroo J, Hafler DA; Anderson; Kuchroo; Hafler (2008). "Lack of TIM-3 Immunoregulation in Multiple Sclerosis". Journal of Immunology. 180 (7): 4409–4414. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4409. PMID 18354161.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Malmeström C, Lycke J, Haghighi S, Andersen O, Carlsson L, Wadenvik H, Olsson B.; Lycke; Haghighi; Andersen; Carlsson; Wadenvik; Olsson (2008). "Relapses in multiple sclerosis are associated with increased CD8(+) T-cell mediated cytotoxicity in CSF". J Neuroimmunol. 196 (Apr.5): 35–40. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.03.001. PMID 18396337.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Satoh J. (2008). "Molecular biomarkers for prediction of multiple sclerosis relapse". Nippon Rinsho (in Japanese). 66 (6): 1103–11. PMID 18540355.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Sheremata WA, Jy W, Horstman LL, Ahn YS, Alexander JS, Minagar A.; Jy; Horstman; Ahn; Alexander; Minagar (2008). "Evidence of platelet activation in multiple sclerosis". J Neuroinflammation. 5 (1): 27. doi:10.1186/1742-2094-5-27. PMC 2474601. PMID 18588683.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Astier AL (2008). "T-cell regulation by CD46 and its relevance in multiple sclerosis". Immunology. 124 (2): 149–54. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02821.x. PMC 2566619. PMID 18384356.

- ^ Kanabrocki EL, Ryan MD, Lathers D, Achille N, Young MR, Cauteren JV, Foley S, Johnson MC, Friedman NC, Siegel G, Nemchausky BA.; Ryan; Lathers; Achille; Young; Cauteren; Foley; Johnson; Friedman; Siegel; Nemchausky (2007). "Circadian distribution of serum cytokines in multiple sclerosis". Clin. Ter. 158 (2): 157–62. PMID 17566518.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rentzos M, Nikolaou C, Rombos A, Evangelopoulos ME, Kararizou E, Koutsis G, Zoga M, Dimitrakopoulos A, Tsoutsou A, Sfangos C.; Nikolaou; Rombos; Evangelopoulos; Kararizou; Koutsis; Zoga; Dimitrakopoulos; Tsoutsou; Sfangos (2008). "Effect of treatment with methylprednisolone on the serum levels of IL-12, IL-10 and CCL2 chemokine in patients with multiple sclerosis in relapse". Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 110 (10): 992–6. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2008.06.005. PMID 18657352.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Scarisbrick IA, Linbo R, Vandell AG, Keegan M, Blaber SI, Blaber M, Sneve D, Lucchinetti CF, Rodriguez M, Diamandis EP.; Linbo; Vandell; Keegan; Blaber; Blaber; Sneve; Lucchinetti; Rodriguez; Diamandis (2008). "Kallikreins are associated with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis and promote neurodegeneration". Biological chemistry. 389 (6): 739–45. doi:10.1515/BC.2008.085. PMC 2580060. PMID 18627300.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ New Control System Of The Body Discovered - Important Modulator Of Immune Cell Entry Into The Brain - Perhaps New Target For The Therapy, Dr. Ulf Schulze-Topphoff, Prof. Orhan Aktas, and Professor Frauke Zipp (Cecilie Vogt-Clinic, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC) Berlin-Buch and NeuroCure Research Center) [7]

- ^ Schulze-Topphoff U, Prat A, Prozorovski T; et al. (July 2009). "Activation of kinin receptor B1 limits encephalitogenic T lymphocyte recruitment to the central nervous system". Nat. Med. 15 (7): 788–93. doi:10.1038/nm.1980. PMID 19561616.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rinta S, Kuusisto H, Raunio M; et al. (October 2008). "Apoptosis-related molecules in blood in multiple sclerosis". J Neuroimmunol. 205 (1–2): 135–41. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.09.002. PMID 18963025.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kuenz B, Lutterotti A, Ehling R; Ehling; Gneiss; Haemmerle; Rainer; Deisenhammer; Schocke; Berger; Reindl; et al. (2008). Zimmer, Jacques (ed.). "Cerebrospinal Fluid B Cells Correlate with Early Brain Inflammation in Multiple Sclerosis". PLoS ONE. 3 (7): e2559. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2559K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002559. PMC 2438478. PMID 18596942.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author2=(help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

- ^ Chiasserini D, Di Filippo M, Candeliere A, Susta F, Orvietani PL, Calabresi P, Binaglia L, Sarchielli P.; Di Filippo; Candeliere; Susta; Orvietani; Calabresi; Binaglia; Sarchielli (2008). "CSF proteome analysis in multiple sclerosis patients by two-dimensional electrophoresis". European Journal of Neurology. 15 (9): 998–1001. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02239.x. PMID 18637954.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Frisullo G, Nociti V, Iorio R; et al. (October 2008). "The persistency of high levels of pSTAT3 expression in circulating CD4+ T cells from CIS patients favors the early conversion to clinically defined multiple sclerosis". J Neuroimmunol. 205 (1–2): 126–34. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.09.003. PMID 18926576.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Proceedings of the National Academy of sciences, complementary information [8]

- ^ a b Quintana FJ, Farez MF, Viglietta V; Viglietta; Iglesias; Merbl; Izquierdo; Lucas; Basso; Khoury; Lucchinetti; Cohen; Weiner; et al. (December 2008). "Antigen microarrays identify unique serum autoantibody signatures in clinical and pathologic subtypes of multiple sclerosis". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (48): 18889–94. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10518889Q. doi:10.1073/pnas.0806310105. PMC 2596207. PMID 19028871.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author2=(help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Quintana08" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Villar LM, Masterman T, Casanova B; et al. (June 2009). "CSF oligoclonal band patterns reveal disease heterogeneity in multiple sclerosis". J. Neuroimmunol. 211 (1–2): 101–4. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.03.003. PMID 19443047.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Linda Ottoboni, Brendan T. Keenan, Pablo Tamayo, Manik Kuchroo, Jill P. Mesirov, Guy J. Buckle, Samia J. Khoury, David A. Hafler, Howard L. Weiner, and Philip L. De Jager. An RNA Profile Identifies Two Subsets of Multiple Sclerosis Patients Differing in Disease Activity. Sci Transl Med, 26 September 2012 doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3004186

- ^ Grant P .Parnell et al. The autoimmune disease-associated transcription factors EOMES and TBX21 are dysregulated in multiple sclerosis and define a molecular subtype of disease, doi:10.1016/j.clim.2014.01.003

- ^ Plumb J, McQuaid S, Mirakhur M, Kirk J; McQuaid; Mirakhur; Kirk (April 2002). "Abnormal endothelial tight junctions in active lesions and normal-appearing white matter in multiple sclerosis". Brain Pathol. 12 (2): 154–69. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00430.x. PMID 11958369.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mancini, M, Cerebral circulation time in the evaluation of neurological diseases [9]

- ^ Meng Law et al. Microvascular Abnormality in Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: Perfusion MR Imaging Findings in Normal-appearing White Matter [10]

- ^ Orbach R, Gurevich M, Achiron A. Interleukin-12p40 in the spinal fluid as a biomarker for clinically isolated syndrome, Mult Scler. 2013 May 30

- ^ Sarchielli P, Greco L, Floridi A, Floridi A, Gallai V.; Greco; Floridi; Floridi; Gallai (2003). "Excitatory amino acids and multiple sclerosis: evidence from cerebrospinal fluid". Arch. Immunol. 60 (8): 1082–8. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.8.1082. PMID 12925363.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Frigo M1 Cogo MG, Fusco ML, Gardinetti M, Frigeni B (2012). "Glutamate and multiple sclerosis". Curr Med Chem. 19 (9): 1295–9. doi:10.2174/092986712799462559. PMID 22304707.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ David Pitt el al. Glutamate uptake by oligodendrocytes. Neurology 2003; 61(8): 1113-1120 doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000090564.88719.37

- ^ Stoop MP, Dekker LJ, Titulaer MK; et al. (2008). "Multiple sclerosis-related proteins identified in cerebrospinal fluid by advanced mass spectrometry". Proteomics. 8 (8): 1576–85. doi:10.1002/pmic.200700446. PMID 18351689.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sarchielli P, Di Filippo M, Ercolani MV; et al. (April 2008). "Fibroblast growth factor-2 levels are elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of multiple sclerosis patients". Neurosci Lett. 435 (3): 223–8. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.040. PMID 18353554.