Virginia Woolf: Difference between revisions

→References: ref |

→Literary commentary: zinck |

||

| Line 687: | Line 687: | ||

==== Literary commentary ==== |

==== Literary commentary ==== |

||

* {{cite book|editor-last1=Barrett|editor-first1=Eileen|editor-last2=Cramer|editor-first2=Patricia|title=Virginia Woolf: Lesbian Readings|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JNQyMMwYVCwC|date= 1997|publisher=[[NYU Press]]|isbn=978-0-8147-1263-4|ref= |

* {{cite book|editor-last1=Barrett|editor-first1=Eileen|editor-last2=Cramer|editor-first2=Patricia|title=Virginia Woolf: Lesbian Readings|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JNQyMMwYVCwC|date= 1997|publisher=[[NYU Press]]|isbn=978-0-8147-1263-4|ref=}} |

||

** {{cite book|last=Cramer|first=Patricia|title=Lesbian readings of Woolf's novels: Introduction|url=https://books.google.coma/books?id=sH8UCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA117|pages=117–127|ref={{harvid|Cramer|1997}}}} |

** {{cite book|last=Cramer|first=Patricia|title=Lesbian readings of Woolf's novels: Introduction|url=https://books.google.coma/books?id=sH8UCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA117|pages=117–127|ref={{harvid|Cramer|1997}}}} |

||

* {{cite book|last=Beja|first=Morris|title=Critical essays on Virginia Woolf|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-6snAQAAMAAJ|year=1985|publisher=[[G. K. Hall & Co.|G.K. Hall]]|isbn=978-0-8161-8753-9|ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book|last=Beja|first=Morris|title=Critical essays on Virginia Woolf|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-6snAQAAMAAJ|year=1985|publisher=[[G. K. Hall & Co.|G.K. Hall]]|isbn=978-0-8161-8753-9|ref=harv}} |

||

| Line 709: | Line 709: | ||

** {{cite book|title=Introduction|pages=1–26|url=http://docshare01.docshare.tips/files/8192/81926159.pdf|ref={{harvid|Sim|2016}}}} |

** {{cite book|title=Introduction|pages=1–26|url=http://docshare01.docshare.tips/files/8192/81926159.pdf|ref={{harvid|Sim|2016}}}} |

||

* {{cite book|last=Transue|first=Pamela J.|title=Virginia Woolf and the Politics of Style|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7h57SNNzy3kC|year=1986|publisher=[[SUNY Press]]|location=Albany, NY|isbn=978-1-4384-2228-2}} |

* {{cite book|last=Transue|first=Pamela J.|title=Virginia Woolf and the Politics of Style|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7h57SNNzy3kC|year=1986|publisher=[[SUNY Press]]|location=Albany, NY|isbn=978-1-4384-2228-2}} |

||

* {{cite book|last=Zink|first=Suzana|title=Virginia Woolf's Rooms and the Spaces of Modernity|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3kFKDwAAQBAJ|date= 2018|publisher=[[Springer Nature]]|isbn=978-3-319-71909-2|ref=}} |

|||

==== Bloomsbury ==== |

==== Bloomsbury ==== |

||

Revision as of 20:57, 18 March 2018

Virginia Woolf | |

|---|---|

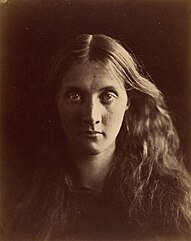

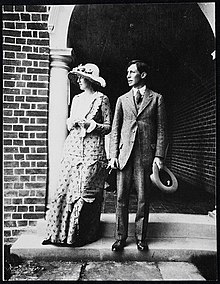

Virginia Woolf 1902 Photo: George Charles Beresford | |

| Born | Adeline Virginia Stephen 25 January 1882 South Kensington, London |

| Died | 28 March 1941 (aged 59) |

| Cause of death | Suicide by drowning |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | King's College London[1] |

| Occupation(s) | Novelist, essayist, publisher, critic |

| Spouse | |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | List

|

| Signature | |

| |

Adeline Virginia Woolf (/wʊlf/;[3] née Stephen; 25 January 1882 – 28 March 1941) was an English writer who is considered one of the most important modernist twentieth century authors and a pioneer in the use of stream of consciousness as a narrative device.

She was born in an affluent household in South Kensington, London, attended the Ladies' Department of King's College and was acquainted with the early reformers of women's higher education. Having been home-schooled for the most part of her childhood, mostly in English classics and Victorian literature, Woolf began writing professionally in 1900. During the interwar period, Virginia Woolf was an important part of London's literary society as well as a central figure in the group of intellectuals known as the Bloomsbury Group. She published her first novel titled The Voyage Out in 1915, through her half-brother’s publishing house, Gerald Duckworth and Company. Her best-known works include the novels Mrs Dalloway (1925), To the Lighthouse (1927) and Orlando (1928). She is also known for her essay A Room of One's Own (1929),[4] where she wrote the much-quoted dictum, "A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction."

Woolf became one of the central subjects of the 1970s movement of feminist criticism, and her works have since garnered much attention and widespread commentary for "inspiring feminism", an aspect of her writing that was unheralded earlier. Her works are widely read all over the world and have been translated into more than fifty languages. She suffered from severe bouts of mental illness throughout her life and took her own life by drowning in 1941 at the age of 59.

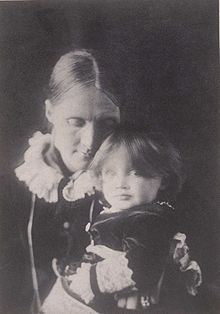

Life

Family of origin

Virginia Woolf was born Adeline Virginia Stephen on 25 January 1882 at 22 Hyde Park Gate in South Kensington, London[6] to Julia (née Jackson) (1846–1895) and Leslie Stephen (1832–1904), writer, historian, essayist, biographer and mountaineer.[6] Julia Jackson was born in 1846 in Calcutta, Bengal, British India to Dr John and Maria (Mia) Pattle Jackson, from two Anglo-Indian families.[7] Dr Jackson FRCS was the third son of George Jackson and Mary Howard of Bengal, a physician who spent 25 years with the Bengal Medical Service and East India Company and a professor at the fledgling Calcutta Medical College. While Dr Jackson was an almost invisible presence, the Pattle family (see Pattle family tree) were famous beauties, and moved in the upper circles of Bengali society.[8] The seven Pattle sisters all married into important families.[9] Julia Margaret Cameron was a celebrated photographer while Virginia married Earl Somers, and their daughter, Julia Jackson's cousin, was Lady Henry Somerset, the temperance leader. Julia moved to England with her mother at the age of two and spent much of her early life with another of her mother's sister, Sarah. Sarah and her husband Henry Thoby Prinsep, conducted an artistic and literary salon at Little Holland House where she came into contact with a number of Pre-Raphaelite painters such as Edward Burne-Jones, who she modelled for.[10]

Julia was the youngest of three sisters and Adeline Virginia Stephen was named after her mother's oldest sister Adeline Maria (1837–1881)[11] and her mother's aunt Virginia (see Pattle family tree and Table of ancestors). Because of the tragedy of her Aunt Adeline’s death the previous year, the family never used Virginia’s first name. The Jacksons were a well educated, literary and artistic proconsular middle-class family.[12][13] In 1867, Julia Jackson married Herbert Duckworth, a barrister,[14] but within three years was left a widow with three infant children.[15] She was devastated and entered a prolonged period of mourning, abandoning her faith and turning to nursing and philanthropy. Julia and Herbert Duckworth had three children;[16]

- George (5 March 1868 – 1934), a senior civil servant, married Lady Margaret Herbert 1904

- Stella (30 May 1869 – 1897), died aged 28[b]

- Gerald (29 October 1870 – 1937), founder of Duckworth Publishing, married Cecil Alice Scott-Chad 1921

Leslie Stephen was born in 1832 in South Kensington to Sir James and Lady Jane Catherine Stephen (née Venn), daughter of John Venn, rector of Clapham. The Venns were the centre of the evangelical Clapham sect. Sir James Stephen was the under secretary at the Colonial Office, and with another Clapham member, William Wilberforce, was responsible for the passage of the Slavery Abolition Bill in 1833.[6][18] In 1849 he was appointed Regius Professor of Modern History at Cambridge University.[19] As a family of educators, lawyers and writers the Stephens represented the elite intellectual aristocracy. While his family were distinguished and intellectual, they were less colourful and aristocratic than Julia Jackson's. A graduate and fellow of Cambridge University he renounced his faith and position to move to London where he became a notable man of letters.[20] In addition he was a rambler and mountaineer, described as a "gaunt figure with the ragged red brown beard...a formidable man, with an immensely high forehead, steely-blue eyes, and a long pointed nose".[c][19] In the same year as Julia Jackson's marriage, he wed Harriet Marian (Minny) Thackeray (1840–1875), youngest daughter of William Makepeace Thackeray, who bore him a daughter, Laura (1870–1945),[d][22] but died in childbirth in 1875. Laura turned out to be developmentally handicapped. and was eventually institutionalised.[23][24]

The widowed Julia Duckworth knew Leslie Stephen through her friendship with Minny's older sister Anne (Anny) Isabella Ritchie and had developed an interest in his agnostic writings. She was present the night Minny died[25] and added Lesley Stephen to her list of people needing care, and helped him move next door to her on Hyde Park Gate so Laura could have some companionship with her own children.[26][27][28][5] Both were preoccupied with mourning and although they developed a close friendship and intense correspondence, agreed it would go no further.[e][29][30] Lesley Stephen proposed to her in 1877, an offer she declined, but when Anny married later that year she accepted him and they were married on March 26, 1878. He and Laura then moved next door into Julia's house, where they lived till his death in 1904. Julia was 32 and Leslie was 46.[24][31]

Their first child, Vanessa, was born on May 30, 1879. Julia, having presented her husband with a child, and now having five children to care for, had decided to limit her family to this.[32] However, despite the fact that the couple took "precautions",[32] "contraception was a very imperfect art in the nineteenth century"[33] resulting in the birth of three more children over the next four years.[f][34][12][35]

22 Hyde Park Gate (1882–1904)

1882–1895

Virginia provides insight into her early life in her autobiographical essays, including Reminiscences (1908),[37] 22 Hyde Park Gate (1921)[38] and A Sketch of the Past (1940).[39] She also alludes to her childhood in her fictional writing. In To The Lighthouse (1927)[40] Her depiction of the life of the Ramsays in the Hebrides is an only thinly disguised account of the Stephens in Cornwall and the Godrevy Lighthouse they would visit there.[41][29][42] However, Woolf's understanding of her mother and family evolved considerably between 1907 and 1940, in which the somewhat distant, yet revered figure of her mother becomes more nuanced and filled in.[43] In 1891, Vanessa and Virginia Stephen began the Hyde Park Gate News,[44] chronicling life and events within the Stephen family,[45][35] while the following year the Stephen sisters also used photography to supplement their insights, as did Stella Duckworth.[46] Vanessa Bell's 1892 portrait of her sister and parents in the Library at Talland House (see image) was one of the family's favourites, and was written about lovingly in Leslie Stephen's memoir.[47]

Virginia was born into a literate and well-connected household of six children, with two half brothers and a half sister (the Duckworths, from her mother's first marriage), another half sister, Laura (from her father's first marriage, and an older sister, Vanessa and brother Thoby. The following year, another brother Adrian followed. The handicapped Laura Stephen lived with the family until she was institutionalised in 1891.[48] Julia and Leslie had four children together:[16]

- Vanessa "Nessa" (30 May 1879 – 1961), married Clive Bell 1907

- Thoby (9 September 1880 – 1906), founded Bloomsbury Group

- Virginia "Jinny", "Ginia" (25 January 1882 – 1941), married Leonard Woolf 1912

- Adrian (27 October 1883 – 1948), married Karin Costelloe 1914

Virginia was born at 22 Hyde Park Gate and lived there till her father's death in 1904. Number 22 Hyde Park Gate, South Kensington, lay at the south east end of Hyde Park Gate, a narrow cul-de-sac running south from Kensington Road, just west of the Royal Albert Hall, and opposite Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park,[49] where the family regularly took their walks (see Map). Built in the early nineteenth century as one of a row of single family townhouses for the upper middle class, it soon became too small for their expanding family. At the time of their marriage, it consisted of a basement, two stories and an attic. In 1886 substantial renovations added a new top floor, converted the attic into rooms, and added the first bathroom.[h] It was a tall but narrow townhouse, that at that time had no running water. Virginia would later describe it as "a very tall house on the left hand side near the bottom which begins by being stucco and ends by being red brick; which is so high and yet—as I can say now that we have sold it—so rickety that it seems as if a very high wond would topple it over"[51]. The servants worked "downstairs" in the basement. The ground floor had a drawing room, separated by a curtain from the servant's pantry and a library. Above this on the first floor were Julia and Leslie's bedrooms. On the next floor were the Duckworth children's rooms, and above them the day and night nurseries of the Stephen children occupied two further floors.[52] Finally in the attic, under the eaves, were the servant's bedrooms, accessed by a back staircase.[22][39][5] Life at 22 Hyde Park Gate was also divided symbolically, as Virginia put it "The division in our lives was curious. Downstairs there was pure convention: upstairs pure intellect. But there was no connection between them", the worlds typified by George Duckworth and Leslie Stephen.[53] Their mother, it seems was the only one who could span this divide.[54][55] The house was described as dimly lit and crowded with furniture and paintings.[56] Within it the younger Stephens formed a close-knit group. Life in London differed sharply from that in Cornwall, their outdoor activities consisting mainly of walks in nearby Hyde Park, and their daily activities around their lessons.[6]

Leslie Stephen's eminence as an editor, critic, and biographer, and his connection to William Thackeray, meant that his children were raised in an environment filled with the influences of Victorian literary society. Henry James, George Henry Lewes, Alfred Tennyson, Thomas Hardy, Edward Burne-Jones and Virginia's honorary godfather, James Russell Lowell, were among the visitors to the house. Julia Stephen was equally well connected. Her aunt was a pioneering early photographer Julia Margaret Cameron who was also a visitor to the Stephen household. The two Stephen sisters, Vanessa and Virginia, were almost three years apart in age, and exhibited some sibling rivalry. Virginia christened her older sister "the saint" and was far more inclined to exhibit her cleverness than her more reserved sister. Virginia resented the domesticity Victorian tradition forced on them, far more than her sister. They also competed for Thoby's affections.[57] Virginia would later confess her ambivalence over this rivalry to Duncan Grant in 1917. "indeed one of the concealed worms of my life has been a sister's jealousy — of a sister I mean; and to feed this I have invented such a myth about her that I scarce know one from t'other".[58]

Virginia showed an early affinity for writing. Although both parents disapproved of formal education for females, writing was considered a respectable profession for women, and her father encouraged her in this respect. Later she would describe this as "ever since I was a little creature, scribbling a story in the manner of Hawthorne on the green plush sofa in the drawing room at St. Ives while the grown-ups dined". By the age of five she was writing letters and could tell her father a story every night. Later she, Vanessa and Adrian would develop the tradition of inventing a serial about their next-door neighbours, every night in the nursery, or in the case of St. Ives, of spirits that resided in the garden. It was her fascination with books that formed the strongest bond between her and her father.[6]

Talland House (1882–1894)

Leslie Stephen was in the habit of hiking in Cornwall, and in the spring of 1881 he came across a large white house[59] in St. Ives, Cornwall, and took out a lease on it that September.[60] Although it had limited amenities,[i] its main attraction was the view overlooking Porthminster Bay towards

the Godrevy Lighthouse,[6] which the young Virginia could see from the upper windows and was to be the central figure in her To the Lighthouse (1927).[40] It was a large square house, with a terraced garden, divided by hedges, sloping down towards the sea.[6] Each year between 1882 and 1894 from mid-July to mid-September the Stephen's leased Talland House[6][61][j] as a summer residence. Leslie Stephen, who referred to it thus: "a pocket-paradise",[62] described it as "The pleasantest of my memories... refer to our summers, all of which were passed in Cornwall, especially to the thirteen summers (1882-1894) at St. Ives. There we bought the lease of Talland House: a small but roomy house, with a garden of an acre or two all up and down hill, with quaint little terraces divided by hedges of escallonia, a grape-house and kitchen-garden and a so-called ‘orchard’ beyond".[63] It was in Leslie's words, a place of "intense domestic happiness".[64] Virginia herself described the house in great detail:

"Our house was...outside the town; on the hill....a square house, like a child's drawing of a house; remarkable only for ts flat roof, and the railing with crossed bars of wood that ran around the roof. It had...a perfect view—right across the Bay to Godrevy Lighthouse. It had, running down the hill, little lawns, surrounded by thick escallonia bushes...it had so many corners and lawns that each was named...it was a large garden—two or three acres at most...You entered Talland House by a large wooden gate...up the carriage drive...to the Lookout place...From the Lookout place one had...a perfectly open view of the Bay....a large lap...flowing to the Lighthouse rocks...with the black and white Lighthouse tower"

Reminiscences 1908, pp. 111–112[37]

In both London and Cornwall, Julia was perpetually entertaining, and was notorious for her manipulation of her guests' lives, constantly matchmaking in the belief everyone should be married, the domestic equivalence of her philanthropy.[12] As her husband observed "My Julia was of course, though with all due reserve, a bit of a matchmaker".[66] While Cornwall was supposed to be a summer respite, Julia Stephen soon immersed herself in the work of caring for the sick and poor there, as well as in London.[61][62][k] Both at Hyde Park Gate and Talland House, the family mingled with much of the country's literary and artistic circles.[39] Frequent guests included literary figures such as Henry James and George Meredith,[66] as well as James Russell Lowell, and the children were exposed to much more intellectual conversations than their mother's at Little Holland House.[56] The family did not return, following Julia Stephen's death in May 1895.[62]

For the children it was the highlight of the year, and Virginia's most vivid childhood memories were not of London but of Cornwall. In a diary entry of 22 March 1921,[67] she described why she felt so connected to Talland House, looking back to a summer day in August 1890. "Why am I so incredibly and incurably romantic about Cornwall? One’s past, I suppose; I see children running in the garden … The sound of the sea at night … almost forty years of life, all built on that, permeated by that: so much I could never explain".[67][6][68] Cornwall inspired aspects of her work, in particular the "St Ives Trilogy" of Jacob's Room (1922),[69] To the Lighthouse (1927),[69] and The Waves (1931).[70][71]

1895–1904

Julia Stephen fell ill with influenza in February 1895, and never properly recovered, dying on 5 May,[72] when Virginia was only 13. This was a pivotal moment in her life and the beginning of her struggles with mental illness.[6] Essentially, her life had fallen apart.[73] The Duckworths were travelling abroad at the time of their mother's death, and Stella returned immediately to take charge and assume her role. That summer, rather than return to the memories of St Ives, the Stephens went to Freshwater, Isle of Wight, where a number of their mother's family lived. It was there that Virginia had the first of her many nervous breakdowns, and Vanessa was forced to assume some of her mother's role in caring for Virginia's mental state.[72] Stella became engaged to Jack Hills the following year and they were married on 10 April 1897, making Virginia even more dependent on her older sister.

George Duckworth also assumed some of their mother's role, taking upon himself the task of bringing them out into society.[73] First Vanessa, then Virginia, in both cases an equal disaster, for it was not a rite of passage which resonated with either girl and attracted a scathing critique by Virgina regarding the conventional expectations of young upper class women "Society in those days was a perfectly competent, perfectly complacent, ruthless machine. A girl had no chance against its fangs. No other desires – say to paint, or to write – could be taken seriously".[l][75] Rather her priorities were to escape from the Victorian conventionality of the downstairs drawing room to a "room of one's own" to pursue her writing aspirations.[73] She would revisit this criticism in her depiction of Mrs Ramsay stating the duties of a Victorian mother in To the Lighthouse "an unmarried woman has missed the best of life".[76]

The death of Stella Duckworth, her pregnant surrogate mother, on 19 July 1897, after a long illness,[77] was a further blow to Virginia's sense of self, and the family dynamics.[78] Woolf described the period following the death of both her mother and Stella as "1897–1904 — the seven unhappy years", referring to "the lash of a random unheeding flail that pointlessly and brutally killed the two people who should, normally and naturally, have made those years, not perhaps happy but normal and natural".[79][73] In April 1902 their father became ill, and although he underwent surgery later that year he never fully recovered, dying on 22 February 1904.[80] Virginia's father's death precipitated a further breakdown.[81] Later, Virginia would describe this time as one in which she was dealt successive blows as a "broken chrysalis" with wings still creased.[6] Chrysalis occurs many times in Woolf's writing but the "broken chrysalis" was an image that became a metaphor for those exploring the relationship between Woolf and grief.[82][83] At his death, Leslie Stephen's net worth was £15,715 6s. 6d.[m] (probate 23 March 1904)[n][86]

Education

In the late nineteenth century, education was sharply divided along gender lines, a tradition that Virginia would note and condemn in her writing.. Boys were sent to school, and in upper-middle-class families such as the Stephens, this involved private boys schools, often boarding schools, and university.[87][88][89][o] Girls, if they were afforded the luxury of education, received it from their parents, governesses and tutors.[95] Virginia was educated by her parents who shared the duty. There was a small classroom off the back of the drawing room, with its many windows, which they found perfect for quiet writing and painting. Julia taught the children Latin, French and History, while Leslie taught them mathematics. They also received piano lessons.[96] Supplementing their lessons was the children's unrestricted access to Leslie Stephen's vast library, exposing them to much of the literary canon,[13] resulting in a greater depth of reading than any of their Cambridge contemporaries, Virginia's reading being described as "greedy".[97] After Public School, the boys in the family all attended Cambridge University. The girls derived some indirect benefit from this, as the boys introduced them to their friends.[98] Another source was the conversation of their father's friends, to whom they were exposed. Leslie Stephen described his circle as "most of the literary people of mark...clever young writers and barristers, chiefly of the radical persuasion...we used to meet on Wednesday and Sunday evenings, to smoke and drink and discuss the universe and the reform movement".[19]

Later, between the ages of 15 and 19 she was able to pursue higher education. She took courses of study, some at degree level, in beginning and advanced Ancient Greek, intermediate Latin and German, together with continental and English history at the Ladies' Department of King's College London at nearby 13 Kensington Square between 1897 and 1901.[p] She studied Greek under the eminent scholar George Charles Winter Warr, professor of Classical Literature at King's.[100] In addition she had private tutoring in German, Greek and Latin. One of her Greek tutors was Clara Pater (1899–1900), who taught at King's.[1][99][101] Another was Janet Case, who involved her in the women's rights movement, and whose obituary Virginia would later write in 1937. Her experiences there led to her 1925 essay On Not Knowing Greek.[102] Her time at King's also brought her into contact with some of the early reformers of women's higher education such as the principal of the Ladies' Department, Lilian Faithfull (one of the so-called Steamboat ladies), in addition to Pater.[103] Her sister Vanessa also enrolled at the Ladies' Department (1899–1901). Although the Stephen girls could not attend Cambridge, they were to be profoundly influenced by their brothers' experiences there. When Thoby went up to Trinity in 1899 he became friends with a circle of young men, including Clive Bell, Lytton Strachey, Leonard Woolf, Saxon Sydney-Turner, that he would soon introduce to his sisters at the Trinity May Ball in 1900. These men formed a reading group they named the Midnight Society.[104][105]

Relationships with family

Although Virginia expressed the opinion that her father was her favourite parent, and although she had only just turned thirteen when her mother died, she was profoundly influenced by her mother throughout her life. It was Virginia who famously stated that "for we think back through our mothers if we are women",[106] and invoked the image of her mother repeatedly throughout her life in her diaries,[107] her letters[108] and a number of her autobiographical essays, including Reminiscences (1908),[37] 22 Hyde Park Gate (1921)[38] and A Sketch of the Past (1940),[39] frequently evoking her memories with the words "I see her ...".[109] She also alludes to her childhood in her fictional writing. In To The Lighthouse (1927)[40] the artist, Lily Briscoe, attempts to paint Mrs Ramsay, a complex character based on Julia Stephen, and repeatedly comments on the fact that she was "astonishingly beautiful".[110] Her depiction of the life of the Ramsays in the Hebrides is an only thinly disguised account of the Stephens in Cornwall and the Godrevy Lighthouse they would visit there.[41][29][42] However, Woolf's understanding of her mother and family evolved considerably between 1907 and 1940, in which the somewhat distant, yet revered figure becomes more nuanced and filled in.[43]

While her father painted Julia Stephen's work in in terms of reverence, Woolf drew a sharp distinction between her mother's work and "the mischievous philanthropy which other women practise so complacently and often with such disastrous results". She describes her degree of sympathy, engagement, judgement and decisiveness, and her sense of both irony and the absurd. She recalls trying to recapture "the clear round voice, or the sight of the beautiful figure, so upright and distinct, in its long shabby cloak, with the head held at a certain angle, so that the eye looked straight out at you".[39] Julia Stephen dealt with her husband's depressions and his need for attention, which created resentment in her children, boosted his self-confidence, nursed her parents in their final illness, and had many commitments outside the home that would eventually wear her down. Her frequent absences and the demands of her husband instilled a sense of insecurity in her children that had a lasting effect on her daughters.[111] In considering the demands on her mother, Woolf described her father as "fifteen years her elder, difficult, exacting, dependent on her" and reflected that this was at the expense of the amount of attention she could spare her young children, "a general presence rather than a particular person to a child",[112][113] reflecting that she rarely ever spent a moment alone with her mother, "someone was always interrupting".[114] Woolf was ambivalent about all this, yet eager to separate herself from this model of utter selflessness. She describes it as "boasting of her capacity to surround and protect, there was scarcely a shell of herself left for her to know herself by"[39] At the same time she admired the strengths of her mother's womanly ideals. Given Julia's frequent absences and commitments, the young Stephen children became increasingly dependent on Stella Duckworth, who emulated her mother's selflessness, as Woolf wrote "Stella was always the beautiful attendant handmaid ... making it the central duty of her life".[115]

Julia Stephen greatly admired her husband's intellect, and although she knew her own mind, thought little of her own. As Woolf observed "she never belittled her own works, thinking them, if properly discharged, of equal, though other, importance with her husband's". She believed with certainty in her role as the centre of her activities, and the person who held everything together,[12] with a firm sense of what was important and valuing devotion. Of the two parents, Julia's "nervous energy dominated the family".[116] While Virginia identified most closely with her father, Vanessa stated her mother was her favourite parent.[117] Angelica Garnett recalls how Virginia asked Vanessa which parent she preferred, although Vanessa considered it a question that "one ought not to ask", she was unequivocal in answering "Mother"[116] Virginia observed that her half-sister, Stella, the oldest daughter, led a life of total subservience to her mother, incorporating her ideals of love and service.[118] Virginia quickly learned, that like her father, being ill was the only reliable way of gaining the attention of her mother, who prided herself on her sickroom nursing.[111][114] Other issues the children had to deal with was Leslie Stephen's temper, Woolf describing him as "the tyrant father".[119][120] Eventually she became deeply ambivalent about her father. He had given her his ring on her eighteenth birthday and she had a deep emotional attachment as his literary heir, writing about her "great devotion for him". Yet, like Vanessa, she also saw him as victimiser and tyrant.[121]

Sexual abuse

Much has been made of Virginia's statements that she was continually sexually abused during the whole time that she lived at 22 Hyde Park Gate, as a possible cause of her mental health issues,[122][123] though there are likely to be a number of contributing factors (see Mental health). Against a background of over committed and distant parents, suggestions that this was a dysfunctional family must be evaluated. These include evidence of sexual abuse of the Stephen girls by their older Duckworth stepbrothers, and by their cousin, James Kenneth Stephen (1859–1892), at least of Stella Duckworth.[q] Laura is also thought to have been abused.[124] The most graphic account is by Louise DeSalvo,[125] but other authors and reviewers have been more cautious.[126][127] Lee states that "The evidence is strong enough, and yet ambiguous enough, to open the way for conflicting psychobiographical interpretations that draw quite different shapes of Virginia Woolf's interior life"[128]

Bloomsbury: life in squares (1904–1941)

Gordon Square (1904–1907)

On their father's death, the Stephens first instinct was to escape from the dark house of yet more mourning, and this they did immediately, accompanied by George, travelling to Manorbier, on the coast of Pembrokeshire on 27 February. There they spent a month, and it was there that Virginia first came to realise her destiny was as a writer, as she recalls in her diary of 3 September 1922.[67] They then further pursued their new found freedom by spending April in Italy and France, where they met up with Clive Bell again.[129] Virginia then suffered her second nervous breakdown, and first suicidal attempt on 10 May, and convalesced over the next three months.[130]

Before their father died, the Stephens had discussed the need to leave South Kensington in the West End, with its tragic memories and their parents' relations.[131] George Duckworth was 35, his brother Gerald 33. The Stephen children were now between 24 and 20. Virginia was 22. Vanessa and Adrian decided to sell 22 Hyde Park Gate in respectable South Kensington and move to Bloomsbury. Bohemian Bloomsbury, with its characteristic leafy squares seemed sufficiently far away, geographically and socially, and was a much cheaper neighbourhood to rent in (see Map). They had not inherited much and they were unsure about their finances.[132] Also Bloomsbury was close to the Slade School which Vanessa was then attending. While Gerald was quite happy to move on and find himself a bachelor establishment, George who had always assumed the role of quasi-parent decided to accompany them, much to their dismay.[132] It was then that Lady Margaret Herbert[r]appeared on the scene, George proposed, was accepted and married in September, leaving the Stephens to their own devices.[133]

Vanessa found a house at 46 Gordon Square in Bloomsbury, and they moved in November, to be joined by Virginia now sufficiently recovered. It was at Gordon Square that the Stephens began to regularly entertain Thoby's intellectual friends in February 1905. The circle now included Lytton Strachey, Clive Bell, Rupert Brooke, E. M. Forster, Saxon Sydney-Turner, Duncan Grant, Leonard Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, David Garnett, and Roger Fry, with Thursday evening "At Homes" that became known as the Thursday Club. This circle formed the nucleus of the intellectual circle of writers and artists known as the Bloomsbury Group.[134][105][135] Also in 1905 Virginia and Adrian visited Portugal and Spain, Clive Bell proposed to Vanessa, but was declined, while Virginia began teaching evening classes at Morley College and Vanessa added another event to their calendar with the Friday Club, dedicated to the fine arts.[134][136] The following year, 1906, Virginia suffered two further losses. Her cherished brother Thoby, who was only 26, died of typhoid, following a trip they had all taken to Greece, and immediately after Vanessa accepted Clive's third proposal.[137][138] Vanessa and Clive were married in February 1907 and as a couple, their interest in avant garde art would have an important influence on Woolf's further development as an author.[139] With Vanessa's marriage, Virginia and Adrian needed to find a new home.[140]

Fitzroy Square (1907–1911) and Brunswick Square (1911–1912)

Virginia moved into 29 Fitzroy Square in April 1907, a house on the west side of the street, formerly occupied by George Bernard Shaw. It was in Fitzrovia, immediately to the west of Bloomsbury but still relatively close to her sister at Gordon Square. The two sisters continued to travel together, visiting Paris in March. Adrian was now to play a much larger part in Virginia's life, and they resumed the Thursday Club in October at their new home, while Gordon Square became the venue for the Play Reading Society in December. Meanwhile, Virginia began work on her first novel, Melymbrosia that eventually became The Voyage Out (1915).[141][140] Vanessa's first child, Julian was born in February 1908, and in September Virginia accompanied the Bells to Italy and France.[142] It was during this time that Virginia's rivalry with her sister resurfaced, flirting with Clive, which he reciprocated, and which lasted on and off from 1908 to 1914, by which time her sister's marriage was breaking down.[143] On 17 February 2009, Lytton Strachey proposed to Virginia and she accepted, but he then withdrew the offer.[144]

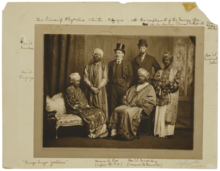

Several members of the group attained notoriety in 1910 with the Dreadnought hoax, which Virginia participated in disguised as a male Abyssinian royal. Her complete 1940 talk on the hoax was discovered and is published in the memoirs collected in the expanded edition of The Platform of Time (2008).[145] It was while she was at Fitzroy Square that the question arose of Virginia needing a quiet country retreat, which she started looking for in December 2010 and soon found a property in Sussex (see below), maintaining a relationship with that area for the rest of her life.[146]

In 1911 Virginia and Adrian decided to give up their home on Fitzroy Square in favour of a different living arrangement, moving to 38 Brunswick Square in Bloomsbury proper[s] in November, with Maynard Keynes and Duncan Grant, and in December they were joined by the writer, Leonard Woolf, an arrangement that continued till late 1912. The house was adjacent to the Foundling Hospital, much to Virginia's amusement since she was an unchaperoned single woman.[147] Duncan Grant decorated Adrian Stephen's rooms (see image).[150]

Marriage (1912–1941)

In May 1912 Virginia agreed to marry Woolf, and the marriage took place on 10 August.[151] The Woolfs continued to live at Brunswick Square till October 1912, when they moved to a small flat at 13 Clifford's Inn, further to the east.[148] Despite his low material status (Woolf referring to Leonard during their engagement as a "penniless Jew") the couple shared a close bond. Indeed, in 1937, Woolf wrote in her diary: "Love-making—after 25 years can't bear to be separate ... you see it is enormous pleasure being wanted: a wife. And our marriage so complete."[152] However, Virginia made a suicide attempt in 1913.[144]

In October 1914, Leonard and Virginia Woolf moved away from Bloomsbury and central London to Richmond, living at 17 The Green, a home discussed by Leonard in his autobiography Beginning Again (1964).[153] In early March 1915, the couple moved again, to nearby Hogarth House, Paradise Road,[154] after which they named their publishing house.[148] Virginia's first novel, The Voyage Out[141] was published in 1915, followed by another suicide attempt. Despite the introduction of conscription in 1916, Leonard was exempted on medical grounds.[148]

Between 1924 and 1939 the Woolfs returned to Bloomsbury, living at 52 Tavistock Square, from where they ran the Hogarth Press from the basement, where Virginia also had her writing room, and is commemorated with a bust of her in the square (see illustration).[155] Their final residence in London was at 37 Mecklenburgh Square (1939–1940), destroyed during the Blitz in September 1940, a month later their previous home on Tavistock Square was also destroyed. After that they made Sussex their permanent home.[156] For descriptions and illustrations of all Virginia Woolf's London homes, see Wilson (1987).

Hogarth Press (1917–1938)

Virginia had taken up book-binding as a pastime in October 1901, at the age of 19,[158][159] and the Woolfs had been discussing setting up a publishing house for some time, and at the end of 1916 started making plans. Having discovered that they were not eligible to enroll in the St Bride School of Printing, they started purchasing supplies after seeking advice from the Excelsior Printing Supply Company on Farringdon Road in March 1917, and soon they had a printing press set up on their dining room table at Hogarth House, and the Hogarth Press was born.[159]

The press subsequently published Virginia's novels along with works by T. S. Eliot, Laurens van der Post, and others.[160] The Press also commissioned works by contemporary artists, including Dora Carrington and Vanessa Bell. Woolf believed that to break free of a patriarchal society that women writers needed a "room of their own" to develop and often fantasised about an "Outsider's Society" where women writers would create a virtual private space for themselves via their writings to develop a feminist critique of society.[161] Though Woolf never created the "Outsider's society", the Hogarth Press was the closest approximation as the Woolfs chose to publish books by writers that took unconventional points of view to form a reading community.[161] Initially the press concentrated on small expermental publications, of little interwest to large commercial publishers. Until 1930, Woolf often helped her husband print the Hogarth books as the money for employees was not there.[161] Virginia relinquished her interest in 1938. After it was bombed in September 1940, the press was moved to Letchworth for the remainder of the war.[162] Both the Woolfs were internationalists and pacifists who believed that promoting understanding between peoples was the best way to avoid another world war and chose quite consciously to publish works by foreign authors of whom the British reading public were unaware.[161] The first non-British author to be published was the Soviet writer Maxim Gorky, the book Reminiscences of Leo Nikolaiovich Tolstoy in 1920, dealing with his friendship with Count Leo Tolstoy.[159]

Vita Sackville-West

The ethos of the Bloomsbury group encouraged a liberal approach to sexuality, and in 1922 she met the writer and gardener Vita Sackville-West, wife of Harold Nicolson. At the time, Sackville-West was the more successful writer both commercially and critically, and it was not until after Woolf's death that she became considered the better writer.[163] After a tentative start, they began a sexual relationship, which, according to Sackville-West in a letter to her husband dated 17 August 1926, was only twice consummated.[164] However, Virginia's intimacy with Vita seems to have continued into the early 1930s.[165] Woolf was also inclined to brag of her affairs with other women within her intimate circle, such as Sibyl Colefax and Comtesse de Polignac.[166]

Sackville-West worked tirelessly to lift up Woolf's self-esteem, encouraging her not to view herself as a quasi-reclusive inclined to sickness who should hide herself away from the world, but rather offered praise for her liveliness and sense of wit, her health, her intelligence and achievements as a writer.[167] Sackville-West led Woolf to reappraise herself, developing a more positive self-image, and the feeling that her writings were the products of her strengths rather than her weakness.[167] Starting at the age of 15, Woolf had believed the diagnosis by her father and his doctor that reading and writing were deleterious to her nervous condition, requiring a regime of physical labour such as gardening to prevent a total nervous collapse. This led Woolf to spend much time obsessively engaging in such physical labour.[167] Sackville-West was the first to argue to Woolf she had been misdiagnosed, and that it was far better to engage in reading and writing to calm her nerves—advice that was taken.[167] Under the influence of Sackville-West, Woolf learned to deal with her nervous ailments by switching between various forms of intellectual activities such as reading, writing and book reviews, instead of spending her time in physical activities that sapped her strength and worsened her nerves.[167] Sackville-West chose the financially struggling Hogarth Press as her publisher in order to assist the Woolfs financially. Seducers in Ecuador, the first of the novels by Sackville-West published by Hogarth, was not a success, selling only 1500 copies in its first year, but the next Sackville-West novel they published, The Edwardians, was a bestseller that sold 30,000 copies in its first six months.[167] Sackville-West's novels, though not typical of the Hogarth Press, saved Hogarth, taking them from the red into the black.[167] However, Woolf was not always appreciative of the fact that it was Sackville-West's books that kept the Hogarth Press profitable, writing dismissively in 1933 of her "servant girl" novels.[167] The financial security allowed by the good sales of Sackville-West's novels in turn allowed Woolf to engage in more experimental work, such as The Waves, as Woolf had to be cautious when she depended upon Hogarth entirely for her income.[167]

In 1928, Woolf presented Sackville-West with Orlando,[168] a fantastical biography in which the eponymous hero's life spans three centuries and both sexes. Nigel Nicolson, Vita Sackville-West's son, wrote, "The effect of Vita on Virginia is all contained in Orlando, the longest and most charming love letter in literature, in which she explores Vita, weaves her in and out of the centuries, tosses her from one sex to the other, plays with her, dresses her in furs, lace and emeralds, teases her, flirts with her, drops a veil of mist around her."[169] After their affair ended, the two women remained friends until Woolf's death in 1941. Virginia Woolf also remained close to her surviving siblings, Adrian and Vanessa; Thoby had died of typhoid fever at the age of 26.[170]

Sussex (1911–1941)

Virginia was needing a country retreat to escape to, and on 24 December 1910 Virginia found a house for rent in Firle, Sussex, near Lewes (see Map). She obtained a lease and took possession of the house the following month, and named it Little Talland House, after their childhood home in Cornwall, although it was actually a new red gabled villa on the main street opposite the village hall.[u][146][171] The lease was a short one and in October she and Leonard Woolf found Asham House[v] at Asheham a few miles to the west, while walking along the Ouse from Firle. The house, at the end of tree-lined road was a strange beautiful Regency-Gothic house in a lonely location (see image).[156] She described it as "flat, pale, serene, yellow-washed", without electricity or water and allegedly haunted.[172] She planned to lease it jointly with Vanessa in the new year, and they moved in in February 1912.[173][174] It was at Asham that the Woolfs spent their wedding night in 1912. At Asham, she recorded the events of the weekends and holidays they spent there in her Asham Diary, part of which was later published as A Writer’s Diary in 1953.[175] In terms of creative writing, The Voyage Out was completed there, and much of Night and Day. Asham provided Woolf with well needed relief from the pace of London life and was where she found a happiness that she expressed in her diary of May 5, 1919 "Oh, but how happy we’ve been at Asheham! It was a most melodious time. Everything went so freely; - but I can’t analyse all the sources of my joy".[176] Asham was the inspiration for A Haunted House (1921-1944),[177][172] and was painted by members of the Bloomsbury Group, including Vanessa Bell and Roger Fry.[178]

While at ‘’Asham’’ Leonard and Virginia found a farmhouse in 1916, that was to let, about four miles away, which they thought would be ideal for her sister. Eventually Vanessa came down to inspect it, and moved in in October of that year, taking it as a summer home for her family. The Charleston Farmhouse was to become the summer gathering place for the literary and artistic circle of the Bloomsbury Group.[179]

In 1919, the Woolf's were forced to relinquish the lease and purchased the Round House in Pipe Passage, Lewes, a converted windmill.[173][174] That same year they discovered Monk's House in nearby Rodmell, which both she and Leonard favoured because of its orchard and garden, and sold the Round House, to purchase it.[180] Monk's House also lacked water and electricity, but came with an acre of garden, and had a view across the Ouse towards the hills of the South Downs. Leonard Woolf describes this view as being unchanged since the days of Chaucer.[181] From 1940 it became their permanent home after their London home was bombed, and Virginia continued to live there until her death in 1941. Meanwhile Vanessa had also made Charleston her permanent home in 1936.[179]

Mental health

Much examination has been made of Woolf's mental health (e.g. see Mental health bibliography). From the age of 13, Woolf suffered periodic mood swings from severe depression to manic excitement, including psychotic episodes, which the family referred to as her "madness".[182][183] Psychiatrists today consider that her illness constitutes bipolar disorder (manic-depressive illness).[184] She spent three short periods in 1910, 1912 and 1913 at Burley House, 15 Cambridge Park, Twickenham, described as "a private nursing home for women with nervous disorder".[185] The death of her father in 1904 provoked her most alarming collapse and she was briefly institutionalised[48] under the care of her father's friend, the eminent psychiatrist George Savage. Savage blamed her education, frowned on by many at the time as unsuitable for women,[95] for her illness.[81][186] She spent time recovering at her friend Violet Dickinson's house, and at her aunt Caroline's house in Cambridge.[187] Though this instability often affected her social life, her literary productivity continued with few breaks throughout her life. Woolf herself provides not only a vivid picture of her symptoms in her diaries and letters, but also her response to the demons that haunted her and at times made her long for death[184] "But it is always a question whether I wish to avoid these glooms....These 9 weeks give one a plunge into deep waters....One goes down into the well & nothing protects one from the assault of truth".[188] Psychiatry had little to offer her in her lifetime, but she recognised that writing was one of the behaviours that enabled her to cope with her illness[184] The only way I keep afloat...is by working....Directly I stop working I feel that I am sinking down, down. And as usual, I feel that if I sink further I shall reach the truth".[189] Sinking under water was Woolf's metaphor for both the effects of depression and psychosis— but also finding truth, and ultimately was her choice of death.[184] Throughout her life Woolf struggled, without success, to find meaning in her illness, on the one hand an impediment, on the other something she visualised as an essential part of who she was, and a necessary condition of her art.[184]

Modern scholars, including her nephew and biographer, Quentin Bell,[190] have suggested her breakdowns and subsequent recurring depressive periods were also influenced by the sexual abuse to which she and her sister Vanessa were subjected by their half-brothers George and Gerald Duckworth (which Woolf recalls in her autobiographical essays A Sketch of the Past and 22 Hyde Park Gate) (see Sexual abuse). It is likely that other factors also played a part. It has been suggested that these include genetic predisposition, for both trauma and family history have been implicated in bipolar disorder.[191] Virginia's father, Leslie Stephen suffered from depression and her half-sister, Laura was institutionalised. Many of Virginia's symptoms, including persistent headache, insomnia, irritability, and anxiety resemble those of her father.[192]

Thomas Caramagno[193] and others,[194] in discussing her illness, warn against the "neurotic-genius" way of looking at mental illness, which rationalises the theory that creativity is somehow born of mental illness.[195][193] Stephen Trombley describes Woolf as having a confrontational relationship with her doctors, and possibly being a woman who is a "victim of male medicine", referring to the contemporary relative lack of understanding about mental illness.[196][197]

Death

After completing the manuscript of her last novel (posthumously published), Between the Acts (1941),[198] Woolf fell into a depression similar to that which she had earlier experienced. The onset of World War II, the destruction of her London home during the Blitz, and the cool reception given to her biography[199] of her late friend Roger Fry all worsened her condition until she was unable to work.[200] When Leonard enlisted in the Home Guard, Virginia disapproved. She held fast to her pacifism and criticized her husband for wearing what she considered to be the silly uniform of the Home Guard.[201] After World War II began, Woolf's diary indicates that she was obsessed with death, which figured more and more as her mood darkened.[202] On 28 March 1941, Woolf drowned herself by filling her overcoat pockets with stones and walking into the River Ouse near her home.[203] Her body was not found until 18 April.[204] Her husband buried her cremated remains beneath an elm tree in the garden of Monk's House, their home in Rodmell, Sussex.[205]

In her suicide note, addressed to her husband, she wrote:

Dearest, I feel certain that I am going mad again. I feel we can't go through another of those terrible times. And I shan't recover this time. I begin to hear voices, and I can't concentrate. So I am doing what seems the best thing to do. You have given me the greatest possible happiness. You have been in every way all that anyone could be. I don't think two people could have been happier till this terrible disease came. I can't fight it any longer. I know that I am spoiling your life, that without me you could work. And you will I know. You see I can't even write this properly. I can't read. What I want to say is I owe all the happiness of my life to you. You have been entirely patient with me and incredibly good. I want to say that—everybody knows it. If anybody could have saved me it would have been you. Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness. I can't go on spoiling your life any longer. I don't think two people could have been happier than we have been. V.[206][207]

Work

Fiction

Woolf is one of the greatest twentieth century novelists and one of the pioneers, among modernist writers[208][209] using stream of consciousness as a narrative device, alongside contemporaries such as Marcel Proust,[210][211] Dorothy Richardson and James Joyce.[212] Woolf's reputation was at its greatest during the 1930s, but declined considerably following World War II. The growth of feminist criticism in the 1970s helped re-establish her reputation.[213][214]

She began writing professionally in 1900, and in November 1904 started sending articles to the editor of the Women's Supplement of The Guardian, the first of which appeared on December 14 of that year,[215] although anonymously, being a review of a visit to Haworth that year, titled Haworth, November 1904.[216][6] From 1905 she wrote for The Times Literary Supplement.[217]

Woolf would go on to publish novels and essays as a public intellectual to both critical and popular acclaim. Much of her work was self-published through the Hogarth Press. "Virginia Woolf's peculiarities as a fiction writer have tended to obscure her central strength: she is arguably the major lyrical novelist in the English language. Her novels are highly experimental: a narrative, frequently uneventful and commonplace, is refracted—and sometimes almost dissolved—in the characters' receptive consciousness. Intense lyricism and stylistic virtuosity fuse to create a world overabundant with auditory and visual impressions".[218] "The intensity of Virginia Woolf's poetic vision elevates the ordinary, sometimes banal settings"—often wartime environments—"of most of her novels".[218]

Her first novel, The Voyage Out,[141] was published in 1915 at the age of 33, by her half-brother's imprint, Gerald Duckworth and Company Ltd. This novel was originally titled Melymbrosia, but Woolf repeatedly changed the draft. An earlier version of The Voyage Out has been reconstructed by Woolf scholar Louise DeSalvo and is now available to the public under the intended title. DeSalvo argues that many of the changes Woolf made in the text were in response to changes in her own life.[219] The novel is set on a ship bound for South America, and a group of young Edwardians onboard and their various mismatched yearnings and misunderstandings. In the novel are hints of themes that would emerge in later work, including the gap between preceding thought and the spoken word that follows, and the lack of concordance between expression and underlying intention, together with how these reveal to us aspects of the nature of love.[220]

"Mrs Dalloway (1925)[221] centres on the efforts of Clarissa Dalloway, a middle-aged society woman, to organise a party, even as her life is paralleled with that of Septimus Warren Smith, a working-class veteran who has returned from the First World War bearing deep psychological scars",[218]

"To the Lighthouse (1927)[40] is set on two days ten years apart. The plot centres on the Ramsay family's anticipation of and reflection upon a visit to a lighthouse and the connected familial tensions. One of the primary themes of the novel is the struggle in the creative process that beset painter Lily Briscoe while she struggles to paint in the midst of the family drama. The novel is also a meditation upon the lives of a nation's inhabitants in the midst of war, and of the people left behind."[218] It also explores the passage of time, and how women are forced by society to allow men to take emotional strength from them.[222]

Orlando: A Biography (1928)[168] is one of Virginia Woolf's lightest novels. A parodic biography of a young nobleman who lives for three centuries without ageing much past thirty (but who does abruptly turn into a woman), the book is in part a portrait of Woolf's lover Vita Sackville-West. It was meant to console Vita for the loss of her ancestral home, Knole House, though it is also a satirical treatment of Vita and her work. In Orlando, the techniques of historical biographers are being ridiculed; the character of a pompous biographer is being assumed in order for it to be mocked.[223]

"The Waves (1931) presents a group of six friends whose reflections, which are closer to recitatives than to interior monologues proper, create a wave-like atmosphere that is more akin to a prose poem than to a plot-centred novel".[218]

Flush: A Biography (1933)[224] is a part-fiction, part-biography of the cocker spaniel owned by Victorian poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning. The book is written from the dog's point of view. Woolf was inspired to write this book from the success of the Rudolf Besier play The Barretts of Wimpole Street. In the play, Flush is on stage for much of the action. The play was produced for the first time in 1932 by the actress Katharine Cornell.

"Her last work, Between the Acts (1941),[198] sums up and magnifies Woolf's chief preoccupations: the transformation of life through art, sexual ambivalence, and meditation on the themes of flux of time and life, presented simultaneously as corrosion and rejuvenation—all set in a highly imaginative and symbolic narrative encompassing almost all of English history."[218] This book is the most lyrical of all her works, not only in feeling but in style, being chiefly written in verse.[225] While Woolf's work can be understood as consistently in dialogue with the Bloomsbury group, particularly its tendency (informed by G. E. Moore, among others) towards doctrinaire rationalism, it is not a simple recapitulation of the coterie's ideals.[18]

Themes

Woolf's fiction has been studied for its insight into many themes including war, shell shock, witchcraft, and the role of social class in contemporary modern British society.[226] In the postwar Mrs. Dalloway (1925),[221] Woolf addresses the moral dilemma of war and its effects[227][228] and provides an authentic voice for soldiers returning from World War I, suffering from shell shock, in the person of Septimus Smith.[229] In A Room of One's Own (1929) Woolf equates historical accusations of witchcraft with creativity and genius among women[230] "When, however, one reads of a witch being ducked, of a woman possessed by devils, ...then I think we are on the track of a lost novelist, a suppressed poet, of some mute and inglorious Jane Austen".[231] Throughout her work Woolf tried to evaluate the degree to which her privileged background framed the lens through which she viewed class.[232][180] She both examined her own position as someone who would be considered an elitist snob, but attacked the class structure of Britain as she found it. In her 1936 essay Am I a Snob?,[233] she examined her values and those of the privileged circle she existed in. She concluded she was, and subsequent critics and supporters have tried to deal with the dilemma of being both elite and a social critic.[234][235][236]

Despite the considerable conceptual difficulties, given Woolf's idiosyncratic use of language,[237] her works have been translated into over 50 languages.[226][238] Some writers, such as the Belgian Marguerite Yourcenar having had rather tense encounters with her, while others such as the Argentinian Jorge Luis Borges produced versions that were highly controversial.[237][214]

Non-fiction

Amongst Woolf's non fiction works, one of the best known is A Room of One's Own (1929).[4] Considered a key work of feminist literary criticism, it was written following two lectures she delivered on "Women and Fiction" at Cambridge University the previous year. In it, she examines the historical disempowerment women have faced in many spheres, including social, educational and financial. One of her most famous dicta is contained within the book "A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction". Much of her argument ("to show you how I arrived at this opinion about the room and the money") is developed through the "unsolved problems" of women and fiction writing to arrive at her conclusion, although she claimed that was only "an opinion upon one minor point".[239]

Influences

A major influence on Woolf from 1912 onward was Russian literature as Woolf adopted many of its aesthetic conventions.[240] The style of Fyodor Dostoyevsky with his depiction of a fluid mind in operation helped to influence Woolf's writings about a "discontinuous writing process", though Woolf objected to Dostoyevsky's obsession with "psychological extremity" and the "tumultuous flux of emotions" in his characters together with his right-wing, monarchist politics as Dostoyevsky was an ardent supporter of the autocracy of the Russian Empire.[240] In contrast to her objections to Dostoyevsky's "exaggerated emotional pitch", Woolf found much to admire in the work of Anton Chekhov and Leo Tolstoy.[240] Woolf admired Chekhov for his stories of ordinary people living their lives, doing banal things and plots that had no neat endings.[240] From Tolstoy, Woolf drew lessons about how a novelist should depict a character's psychological state and the interior tension within.[240] From Ivan Turgenev, Woolf drew the lessons that there are multiple "I's" when writing a novel, and the novelist needed to balance those multiple versions of him- or herself to balance the "mundane facts" of a story vs. the writer's overreaching vision, which required a "total passion" for art.[240]

Another influence on Woolf was the American writer Henry David Thoreau, with Woolf writing in a 1917 essay that her aim as a writer was to follow Thoreau by capturing "the moment, to burn always with this hard, gem-like flame" while praising Thoreau for his statement "The millions are awake enough for physical labor, but only one in hundreds of millions is awake enough to a poetic or divine life. To be awake is to be alive".[241] Woolf praised Thoreau for his "simplicity" in finding "a way for settling free the delicate and complicated machinery of the soul".[241] Like Thoreau, Woolf believed that it was silence that set the mind free to really contemplate and understand the world.[241] Both authors believed in a certain transcendental, mystical approach to life and writing, where even banal things could be capable of generating deep emotions if one had enough silence and the presence of mind to appreciate them.[241] Woolf and Thoreau were both concerned with the difficulty of human relationships in the modern age.[241] Other notable influences include William Shakespeare, George Eliot, Leo Tolstoy, Marcel Proust, Anton Chekhov, Emily Brontë, Daniel Defoe, James Joyce, and E. M. Forster.

List of selected publications

see Kirkpatrick & Clarke (1997)

Novels

- Woolf, Virginia (2017) [1915]. The voyage out. FV Éditions. ISBN 979-10-299-0459-2. see also The Voyage Out & Complete text

- — (2015) [1922]. Jacob's Room. Mondial. ISBN 978-1-59569-114-9. see also Jacob's Room & Complete text

- — (2012) [1925]. Mrs. Dalloway. Broadview Press. ISBN 978-1-55111-723-2. see also Mrs Dalloway & Complete text

- — (2004) [1927]. To the Lighthouse. Collector's Library. ISBN 978-1-904633-49-5. see also To the Lighthouse & Complete text, also Texts at Woolf Online

- Woolf, Virginia (2006) [1928]. DiBattista, Maria (ed.). Orlando (Annotated): A Biography. HMH. ISBN 978-0-547-54316-1. see also Orlando: A Biography & Complete text

- — (2000) [1931]. The Waves. Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 978-1-84022-410-8. see also The Waves & Complete text

- — (2014) [1941]. Between the Acts. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-544-45178-0. see also Between the Acts & Complete text

Short stories

- Woolf, Virginia (2016) [1944]. The Short Stories of Virginia Woolf. Read Books Limited. ISBN 978-1-4733-6304-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) see also A Haunted House and Other Short Stories & Complete text

Cross-genre

- Woolf, Virginia (1998) [1933]. Flush. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-283328-0. see also Flush: A Biography & Complete text

Non-fiction

- Woolf, Virginia (2016) [1929]. A Room of One's Own. Read Books Limited. ISBN 978-1-4733-6305-2. see also A Room of One's Own & Complete text

- — (2016) [1938]. Three Guineas. Read Books Limited. ISBN 978-1-4733-6301-4. see also Three Guineas & Complete text

- — (2017) [1940]. Roger Fry: A Biography. Musaicum Books. ISBN 978-80-272-3516-2. see also Roger Fry: A Biography & Complete text

Essays

- Woolf, Virginia (2009). Bradshaw, David (ed.). Selected Essays. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-955606-9.

- Woolf, Virginia (2017). The Greatest Essays of Virginia Woolf. Musaicum Books. ISBN 978-80-272-3514-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - — (14 December 1904). "Haworth, November 1904". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Autobiographical writing

- Woolf, Virginia (2003) [1953]. Woolf, Leonard (ed.). A Writer's Diary. HMH. ISBN 978-0-547-54691-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editorlink=ignored (|editor-link=suggested) (help) - — (1985) [1976]. Schulkind, Jeanne (ed.). Moments of being: unpublished autobiographical writings (2nd ed.). Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 978-0-15-162034-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) (see Moments of Being)- Schulkind, Jeanne. Preface to the Second Edition. p. 6., in Woolf (1985)

- Schulkind, Jeanne. Introduction. pp. 11–24., in Woolf (1985)

- Reminiscences. 1908. pp. 25–60.

- A Sketch of the Past. 1940. pp. 61–160.[w] (excerpts — 1st ed.)

- Memoir Club Contributions

- 22 Hyde Park Gate. 1921. pp. 162–178.

- Old Bloomsbury. 1922. pp. 179–202.

- Am I a Snob?. 1936. pp. 203–220.

Diaries and letters

- Woolf, Virginia (1977–1984). Bell, Anne Oliver (ed.). The Diary of Virginia Woolf 5 vols. Houghton Mifflin.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)- — (1979). The Diary of Virginia Woolf Volume One 1915–1919. ISBN 978-0-544-31037-7.

- — (1981). The Diary of Virginia Woolf Volume Two 1920–1924. ISBN 978-0-14-005283-1.

- — (1978). The Diary of Virginia Woolf Volume Three 1925–1930.

- — (1985). The Diary Of Virginia Woolf Volume Five 1936-1941. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-15-626040-4.

- — (2008). Rosenbaum, S. P. (ed.). The Platform of Time: Memoirs of Family and Friends. Hesperus Press. ISBN 978-1-84391-711-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - — (1975–1980). Nicolson, Nigel; Banks, Joanne Trautmann (eds.). The Letters of Virginia Woolf 6 vols. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|editorlink1=ignored (|editor-link1=suggested) (help)- — (1982). The Letters of Virginia Woolf: 1932-1935. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 978-0-15-650886-5.

Photograph albums

- Woolf, Virginia (1983). "Virginia Woolf Monk's House photographs, ca. 1867-1967 (MS Thr 564)" (Guide). Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard Library. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

Collections

- Woolf, Virginia (2013). Delphi Complete Works of Virginia Woolf (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. ISBN 978-1-908909-19-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)- Selected complete texts: — (2015). "eBooks@Adelaide". Library of University of Adelaide. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- Excerpted selections: — (2017a). The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf. Musaicum Books. ISBN 978-80-272-1784-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Views

Though happily married to a Jewish man, Woolf often wrote of Jewish characters in stereotypical archetypes and generalisations, including describing some of her Jewish characters as physically repulsive and dirty.[243] For example, while travelling on a cruise to Portugal she protests at finding "a great many Portuguese Jews on board, and other repulsive objects, but we keep clear of them".[244] Furthermore, she wrote in her diary: "I do not like the Jewish voice; I do not like the Jewish laugh." In a 1930 letter to the composer Ethel Smyth, quoted in Nigel Nicolson's biography Virginia Woolf, she recollects her boasts of Leonard's Jewishness confirming her snobbish tendencies, "How I hated marrying a Jew—What a snob I was, for they have immense vitality."[245]

In another letter to Smyth, Woolf gives a scathing denunciation of Christianity, seeing it as self-righteous "egotism" and stating "my Jew has more religion in one toenail—more human love, in one hair."[246] Woolf claimed in her private letters that she thought of herself as an atheist.[247]

Woolf and her husband Leonard came to despise and fear the 1930s fascism and antisemitism. Her 1938 book Three Guineas[248] was an indictment of fascism and what Woolf described as a recurring propensity among patriarchal societies to enforce repressive societal mores by violence.[249]

Modern scholarship and interpretations

Though at least one biography of Virginia Woolf appeared in her lifetime, the first authoritative study of her life was published in 1972 by her nephew Quentin Bell. Hermione Lee's 1996 biography Virginia Woolf[200] provides a thorough and authoritative examination of Woolf's life and work, which she discussed in interview in 1997.[250] In 2001 Louise DeSalvo and Mitchell A. Leaska edited The Letters of Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf. Julia Briggs's Virginia Woolf: An Inner Life (2005) focuses on Woolf's writing, including her novels and her commentary on the creative process, to illuminate her life. The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu also uses Woolf's literature to understand and analyse gender domination.

Historical feminism

"Recently, studies of Virginia Woolf have focused on feminist and lesbian themes in her work, such as in the 1997 collection of critical essays, Virginia Woolf: Lesbian Readings, edited by Eileen Barrett and Patricia Cramer."[218] In 1928, Virginia Woolf took a grassroots approach to informing and inspiring feminism. She addressed undergraduate women at the ODTAA Society at Girton College, Cambridge and the Arts Society at Newnham College with two papers that eventually became A Room of One’s Own (1929).[4] Woolf's best-known nonfiction works, A Room of One's Own (1929)[4] and Three Guineas (1938),[248] examine the difficulties that female writers and intellectuals faced because men held disproportionate legal and economic power, as well as the future of women in education and society, as the societal effects of industrialization and birth control had not yet fully been realized.[citation needed] In The Second Sex (1949), Simone de Beauvoir counts, of all women who ever lived, only three female writers—Emily Brontë, Woolf and "sometimes" Katherine Mansfield— have explored "the given."[251]

In popular culture

- Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? is a 1962 play by Edward Albee. It examines the structure of the marriage of an American middle-aged academic couple, Martha and George. Mike Nichols directed a film version in 1966, starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. Taylor won the 1966 Academy Award for Best Actress for the role.

- Me! I'm Afraid of Virginia Woolf, a 1978 TV play, references the title of the Edward Albee play and features an English literature teacher who has a poster of her. It was written by Alan Bennett and directed by Stephen Frears.

- The artwork The Dinner Party (1979) features a place setting for Woolf.[252]

- Michael Cunningham's 1998 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Hours focused on three generations of women affected by Woolf's novel Mrs Dalloway. In 2002, a film version of the novel was released starring Nicole Kidman as Woolf.

- Susan Sellers' novel Vanessa and Virginia (2008) explores the close sibling relationship between Woolf and her sister, Vanessa Bell. It was adapted for the stage by Elizabeth Wright in 2010 and first performed by Moving Stories Theatre Company.

- Priya Parmar's 2014 novel Vanessa and Her Sister also examined the Stephen sisters' relationship during the early years of their association with what became known as the Bloomsbury Group.[253]

- An exhibition on Virginia Woolf was held at the National Portrait Gallery from July to October 2014.[254]

- Virginia is portrayed by both Lydia Leonard and Catherine McCormack in the BBC's three-part drama series Life in Squares (2015).[255]

- On 25 January 2018, Google showed a doodle celebrating her 136th birthday.[256]

Legacy

Virginia Woolf is known for her contributions to twentieth century literature and her essays, as well as the influence she has had on literary, particularly feminist criticism. A number of authors have stated that their work was influenced by Virginia Woolf, including Margaret Atwood, Michael Cunningham,[x] Gabriel García Márquez,[y] and Toni Morrison.[z] Her iconic image[260] is instantly recognisable from the Beresford portrait of her at twenty (at the top of this page) to the Beck and Macgregor portrait in her mother's dress in Vogue at forty four (see image) or Man Ray's cover of Time magazine (see image) at 55.[261] More postcards of Woolf are sold by the National Portrait Gallery, London than any other person.[262] Her image is ubiquitous, and can be found on tea towels to T shirts.[261]

In addition to organisations dedicated to the study of Virginia Woolf, like the Virginia Woolf Society,[263] trusts such as the Asham Trust have been set up to encourage writers, in her honour.[176] Although she had no descendants, a number of her extended family are notable.[264]

Monuments and memorials

In 2013 Woolf was honoured by her alma mater of King's College London with the opening of the Virginia Woolf Building on Kingsway, with a plaque commemorating her time there and her contributions (see image),[265][266] together with an this exhibit depicting her accompanied by a quotation "London itself perpetually attracts, stimulates, gives me a play & a story & a poem" from her 1926 diary.[267] Busts of Virginia Woolf have been erected at her home in Rodmell, Sussex and at Tavistock Square, London where she lived between 1924 and 1939.

Family trees

see Lee 1999, pp. xviii–xvix, Bell 1972, pp. x–xi, Bicknell 1996, p. xx harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBicknell1996 (help),Venn 1904

| Family of Virginia Woolf | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||