American Eagle Flight 4184

This article may contain improper use of non-free material. (August 2024) |

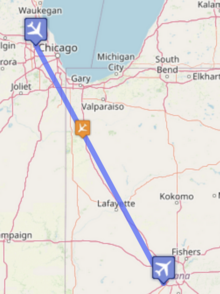

Aerial view of the crash site | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | October 31, 1994 |

| Summary | Atmospheric icing leading to loss of control[1] |

| Site | Lincoln Township, Newton County, Indiana, U.S. 41°5′40″N 87°19′20″W / 41.09444°N 87.32222°W |

| Aircraft | |

An American Eagle ATR 72–212 similar to the accident aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | ATR 72–212 |

| Operator | Simmons Airlines d/b/a American Eagle |

| Call sign | EAGLE FLIGHT 184 |

| Registration | N401AM |

| Flight origin | Indianapolis International Airport |

| Destination | O'Hare International Airport |

| Occupants | 68 |

| Passengers | 64 |

| Crew | 4 |

| Fatalities | 68 |

| Survivors | 0 |

American Eagle Flight 4184, officially operating as Simmons Airlines Flight 4184, was a scheduled domestic passenger flight from Indianapolis, Indiana, to Chicago, Illinois, United States. On October 31, 1994, the ATR 72 performing this route flew into severe icing conditions, lost control and crashed into a field, killing all 68 people on board in the high-speed impact.[1]

Background

[edit]Aircraft

[edit]

The aircraft involved, registration N401AM,[2] was built by the French-Italian aircraft manufacturer ATR and was powered by two Pratt & Whitney Canada PW127 turboprops.[3] It made its first flight on March 7, 1994, and was delivered to American Eagle on March 24, 1994. It was operated by Simmons Airlines on behalf of American Eagle.[1]: 1 [4][5] American Eagle was the banner carrier regional airline branding program of AMR Corporation's regional system, prior to the formation of the fully certificated carrier named American Eagle Airlines.

Passengers and crew

[edit]| Nation | Passengers | Crew | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Colombia | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Lesotho | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Mexico | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| South Korea | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Sweden | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| United Kingdom | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| United States | 49[a] | 4 | 53 |

| Total Fatalities | 64 | 4 | 68 |

The captain of Flight 4184 was Orlando Aguilar, 29. He was an experienced pilot with almost 8,000 hours of flight time, including 1,548 hours in the ATR.[1]: 13 Colleagues described Aguilar's flying skills in positive terms and commented on the relaxed cockpit atmosphere that he promoted.[1]: 13 The first officer was Jeffrey Gagliano, 30. His colleagues also considered him to be a competent pilot, and he had accumulated more than 5,000 flight hours, including 3,657 hours in the ATR.[1]: 14 There were two flight attendants, one of whom was on her first day in the job.

Weather

[edit]National Weather Service reports revealed low cloud ceilings and visibility under three miles in the area. The air temperature was approximately 45 °F (7 °C) at the accident site but 0 °F (−18 °C) at 18,000 feet (5,500 m), with precipitation in the air.

The weather conditions provided by Lowell Airport, located about 12 nautical miles (14 mi; 22 km) northwest of the accident site, indicated broken clouds at 1,400 feet (430 m) and an overcast sky at 3,000 feet (910 m) with gusty winds from the southwest at 20 knots (23 mph; 37 km/h; 10 m/s) and light drizzle. However, the report observation was made about 30 minutes after the accident.[1]: 17

Flight

[edit]This section needs expansion with: more information from the report. You can help by adding to it. (February 2020) |

The flight was en route from Indianapolis International Airport, Indiana (IND) to O'Hare International Airport, Chicago, Illinois (ORD). Flight 4184 was scheduled to depart the gate in IND at 14:10 and arrive in ORD at 15:15; however, due to deteriorating weather conditions at ORD, the flight left the gate at 14:14 and was held on the ground for 42 minutes before receiving an IFR clearance to ORD. The controller did not specify to the crew the reason for the hold.

The flight crew engaged the autopilot as the airplane climbed through 1,800 feet (549 m). At 15:05:14, the captain made initial radio contact with the DANVILLE Sector (DNV) Radar Controller and reported that they were at 10,700 feet (3,261 m) and climbing to 14,000 feet (4,267 m). The DNV controller issued a clearance to the crew to proceed directly to the Chicago Heights VOR. At 15:08:33, the captain of flight 4184 requested and received a clearance to continue the climb to the final en route altitude of 16,000 feet (4,877 m).

At 15:09:22, the pilot of a Beech Baron, N7983B, provided a pilot report (PIREP) to the DNV controller that there was "light icing" at 12,000 feet (3,658 m) over Lafayette, and, 22 seconds later, added that the icing was "trace rime...." According to the DNV controller, because the crew of flight 4184 was on the frequency and had established radio contact, the PIREP was not repeated.

At 15:13, flight 4184 began the descent to 10,000 feet (3,048 m) with first officer Gagliano at the controls. During the descent, the flight data recorder (FDR) recorded the activation of the Level III airframe deicing system and the propeller RPM at 86 percent.

At 15:17:24, the BOONE sector was advised by the ORD traffic controller to issue holding instructions to all inbound aircraft.

At 15:18:07, shortly after flight 4184 leveled off at 10,000 feet, the BOONE controller notified the crew that they were cleared to the LUCIT intersection and gave their holding pattern, telling them to expect further clearance (EFC) at 15:30. The captain acknowledged the transmission. About 1 minute later, the BOONE controller revised the EFC for flight 4184 to 15:45. This was followed a short time later by several radio transmissions between the captain of flight 4184 and the BOONE controller in which he received approval for 10-nautical-mile (12 mi; 19 km) legs in the holding pattern, a speed reduction, and confirmation of right turns while holding.

At 15:24:39, the captain of flight 4184 contacted the BOONE controller and reported, "entering the hold." The first holding pattern was flown at approximately 175 knots (201 mph; 324 km/h) with the wing flaps in the retracted position. The airframe deice system was deactivated during this time, and the propeller speed was reduced to 77 percent.

At 15:33:13, the captain stated, "man this thing gets a high deck angle in these turns...we're just wallowing in the air right now." FDR data indicated that the angle-of-attack (AOA) was 5 degrees. Following this comment, the first officer moved the flaps to the 15-degree position and the aircraft returned to level flight.

At 15:38:42, the BOONE controller issued a revised EFC of 1600 to flight 4184. The captain acknowledged this transmission, and the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) recorded the flight crew continuing their discussion with the flight attendant. At 15:41:07, the CVR recorded the sound of a single tone similar to the caution alert chime, and the FDR recorded the activation of the "Level III" airframe deicing systems. About 3 seconds later, both the CVR and FDR recorded an increase in the propeller speed from 77 percent to 86 percent, as required by Level III icing conditions.

At 15:48:34, the first officer commented to the captain, "that's much nicer, flaps fifteen." About 7 seconds later, the CVR recorded one of the two pilots saying, "I'm showing some ice now." The captain remarked shortly thereafter, "I'm sure that once they let us out of the hold and forget they're down we'll get the overspeed," referencing the aural flap overspeed warning that activates if the aircraft speed exceeds 185 knots (213 mph; 343 km/h) with flaps in the 15-degree position.

At 15:49:44, the captain departed the cockpit and went to the aft portion of the airplane to use the restroom. The captain returned from the restroom at 15:54:13, and upon his return asked the first officer for a status update regarding company and ATC communications. There was no verbal inquiry by the captain about the status of the icing conditions or the aircraft deice/anti-icing systems. At 15:55:42, the first officer commented, "we still got ice." This comment was not verbally acknowledged by the captain. The CVR indicated that the flightcrew had no further discussions regarding the icing conditions.

At 15:56:16, the BOONE controller contacted flight 4184 and instructed the flight crew to, "descend and maintain eight thousand [feet]." This was followed by a transmission from the BOONE controller informing the crew that "...[it] should be about ten minutes till you're cleared in." The first officer responded, "thank you." There were no further radio communications with the crew of flight 4184.

Accident

[edit]At 15:56:51, the FDR showed that the airplane began to descend from 10,000 feet (3,048 m), the engine power was reduced to the flight idle position, the propeller speed was 86 percent, and the autopilot remained engaged in the vertical speed and heading select modes. At 15:57:21, as the airplane was descending in a 15-degree right-wing-down attitude at 186 knots (214 mph; 344 km/h), the sound of the flap overspeed warning was recorded on the CVR. Five seconds later, the captain commented, "I knew we'd do that." As the flaps began transitioning to the zero degree position, the AOA and pitch attitude began to increase.

At 15:57:33, as the airplane was descending through 9,130 feet (2,783 m), the AOA increased through 5 degrees, and the ailerons began deflecting to a right-wing-down position. About half a second later, the ailerons rapidly deflected to 13.43 degrees right wing down (maximum designed aileron deflection is 14 degrees in either direction from neutral), the autopilot disconnected, and the CVR recorded the sounds of the autopilot disconnect warning (a repetitive triple chirp that is manually silenced by the pilot). The airplane rolled rapidly to the right, and the pitch attitude and AOA began to decrease.

Within several seconds of the initial aileron and roll excursion, the AOA decreased through 3.5 degrees, the ailerons moved to a nearly neutral position, and the airplane stopped rolling at 77 degrees right wing down. The airplane then began to roll to the left toward a wings-level attitude, the elevator began moving in a nose-up direction, the AOA began increasing, and the pitch attitude stopped at approximately 15 degrees nose down.

Five seconds later, as the airplane rolled back to the left through 59 degrees right wing down (towards wings level), the AOA increased again through 5 degrees and the ailerons again deflected rapidly to a right wing down position. The captain's nose-up control column force exceeded 22 pounds, and the airplane rolled rapidly to the right, at a rate in excess of 50 degrees per second, bringing the plane completely inverted.

As the airplane rolled through 120 degrees, the captain's nose-up control column force decreased below 22 pounds, and the first officer's nose-up control column force exceeded 22 pounds just after the airplane rolled through the inverted position (180 degrees). Throughout this roll, the data recorder showed that the first officer was sustaining nose-up elevator inputs. After the aircraft completed a full right roll and passed through a wings-level attitude, the captain said "alright man" and the first officer's nose-up control column force decreased below 22 pounds. The nose-up elevator and AOA then decreased rapidly, the ailerons immediately deflected to 6 degrees left wing down and then stabilized at about 1 degree right wing down, and the airplane stopped rolling at 144 degrees right wing down, a steep right bank.

Fifteen seconds after the autopilot first disconnected, the airplane began rolling left, back towards wings level. The airspeed increased through 260 knots (299 mph; 482 km/h), the pitch attitude decreased through 60 degrees nose down, acceleration fluctuated between 2.0 and 2.5 G, and altitude decreased through 6,000 feet. At 15:57:51, as the roll attitude passed through 90 degrees, continuing towards wings level, the captain applied more than 22 pounds of nose-up control column force, the elevator position increased to about 3 degrees nose up, pitch attitude stopped decreasing at 73 degrees nose down, the airspeed increased through 300 knots (345 mph; 556 km/h), normal acceleration remained above 2 G, and the altitude decreased through 4,900 feet (1,494 m).

At 15:57:53, as the captain's nose-up control column force decreased below 22 pounds, the first officer's nose-up control column force again exceeded 22 pounds and the captain made the statement "nice and easy." At 15:57:55, the normal acceleration increased to over 3.0 G, the sound of the ground proximity warning system (GPWS) alert was recorded on the CVR, and the captain's nose-up control column force again exceeded 22 pounds. Approximately 1.7 seconds later, as the altitude decreased through 1,700 feet (518 m), the first officer made an expletive comment, the elevator position and vertical acceleration began to increase rapidly, and the CVR recorded a loud "crunching" sound. The last recorded data on the FDR occurred at an altitude of 1,682 feet (513 m) (vertical speed of approximately 500 feet per second [150 m/s]), and indicated that the airplane was at an indicated airspeed of 375 knots (432 mph; 694 km/h), a pitch attitude of 38 degrees nose down with 5 degrees of nose-up elevator, and was experiencing a vertical acceleration of 3.6 G. The CVR continued to record the loud crunching sound for an additional 0.4 seconds.

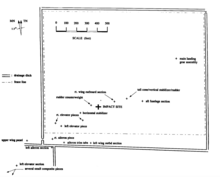

The airplane impacted a wet soybean field in Lincoln Township, Newton County, Indiana, partially inverted, in a nose down, left-wing-low attitude. The NTSB determined that the accident was not survivable because the impact forces exceeded human tolerances, and no occupiable space remained intact.[1]

The distribution of wreckage, combined with data from the flight recorders, indicated that the horizontal stabilizer and outboard sections of both wings separated from the airplane prior to impact, "in close proximity to the ground." As the bodies of all on board were fragmented by the impact forces, the crash site was declared a biohazard.[1]: 73

Flight 4184 was the first hull loss, and was also tied with Aero Caribbean Flight 883 as the deadliest aviation accident involving an ATR 72 aircraft, until Yeti Airlines Flight 691 crashed in 2023.

Probable cause

[edit]In its report, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) found that the aircraft manufacturer ATR, the French Directorate General for Civil Aviation (the French counterpart of the American FAA) and the FAA itself had each contributed to the accident by failing to achieve the highest possible level of safety.

The unabridged NTSB probable cause statement reads:

3.2 Probable Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable causes of this accident were the loss of control, attributed to a sudden and unexpected aileron hinge moment reversal that occurred after a ridge of ice accreted beyond the deice boots because: 1) ATR failed to completely disclose to operators, and incorporate in the ATR 72 airplane flight manual, flightcrew operating manual and flightcrew training programs, adequate information concerning previously known effects of freezing precipitation on the stability and control characteristics, autopilot and related operational procedures when the ATR 72 was operated in such conditions; 2) the French Directorate General for Civil Aviation's (DGAC's) inadequate oversight of the ATR 42 and 72, and its failure to take the necessary corrective action to ensure continued airworthiness in icing conditions; and 3) the DGAC's failure to provide the FAA with timely airworthiness information developed from previous ATR incidents and accidents in icing conditions, as specified under the Bilateral Airworthiness Agreement and Annex 8 of the International Civil Aviation Organization.

Contributing to the accident were: 1) the Federal Aviation Administration's (FAA's) failure to ensure that aircraft icing certification requirements, operational requirements for flight into icing conditions, and FAA published aircraft icing information adequately accounted for the hazards that can result from flight in freezing rain and other icing conditions not specified in 14 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 25, Appendix C; and 2) the FAA's inadequate oversight of the ATR 42 and 72 to ensure continued airworthiness in icing conditions.[1]: 210

BEA response and investigation

[edit]This section needs expansion with: information from the BEA's comments on the accident. You can help by adding to it. (February 2020) |

The French Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety (BEA) conducted its own separate investigation and agreed with the NTSB's cause of the accident as aileron deflection leading to loss of control. However, the BEA stated in its response to the NTSB's report that the aileron deflection was caused by pilot error instead of by ice, citing several off-topic conversations made by the crew during the holding phase as well as the flight crew's extension of the flaps to 15 degrees while at a high speed, which can create large axial loads. The BEA also stated that the air-traffic controller was not adequately monitoring the flight.[7] However, the NTSB refuted the BEA's arguments in its final report and in a separate detailed response article. In addition, there was no factual evidence to support the BEA's claims. The NTSB stated that the crew's conversation took place at a non-critical moment of the flight and that the pilots were aware of the ice on the wings. Therefore, the NTSB concluded that the non-pertinent conversation did not contribute to the accident.[citation needed]

Aftermath

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: Most of this was written more than 10 years ago. There have been crashes of this type of aircraft since then that were caused by icing. Also, some of the claims below come without references. (February 2020) |

In March 1995, some families of the victims discovered remains of their loved ones at the accident site, giving rise to a suspicion that cleanup efforts were not thorough. In a statement, the Newton County coroner – referring to other comments made – said he was not surprised there were remains left, given how serious the accident was.[8]

In April 1996, the FAA issued 18 Airworthiness Directives (ADs) affecting 29 turboprop aircraft having the combination of unpowered flight controls, pneumatic deicing boots and NACA "five-digit sharp-stall" airfoils. They included significant revisions of pilot operating procedures in icing conditions (higher minimum speeds, manual control and different upset recovery procedures) as well as physical changes to the coverage area of the deicing boots on the airfoils.[citation needed]

In the years following the accident, AMR stopped flying its American Eagle ATRs out of its northern hubs and moved them to its southern and Caribbean hubs at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, Miami, Florida, and San Juan, Puerto Rico, to reduce potential icing problems in the future. Other American ATR operators, particularly Atlantic Southeast Airlines, operated ATR 72 aircraft in areas where icing conditions were not common.[citation needed]

Robert Boser, editor at airlinesafety.com, stated:[9]

The ADs require extensive instruction, to pilots flying the affected aircraft, on how to fly in freezing rain and drizzle (including the prohibition of the use of the autopilot in icing conditions), how to recognize indications of severe icing, and then require an immediate exit from icing areas. In addition, both ATR-42 and ATR-72 aircraft had their deicing boots modified to extend the boot area to reach back to 12.5 % of the chord. Previously, they had extended only to 5 % and 7 %, respectively. In theory, that should solve the problem of the tendency of ice ridge formation at the 9% chord position of those obsolete sharp-stall airfoils.

However, it still doesn't deal with the results of the Boscombe Downs tests, conducted by the British, which demonstrated ice could form as far back on the wing as 23% of the chord, and on the tail at 30% of chord. Both percentages remain well beyond the limits of the deicing boots. Those tests limited the size of the droplets to 40 microns, near the maximum limit of the archaic FAA design certification rules for Transport Category aircraft (Part 25, Appendix C), still in effect at that time of the Roselawn crash.

Boser further noted "it is possible for airliners to encounter water droplets exceeding 200 microns in average diameter".[9]

It is likely that the lack of further ATR icing accidents during the 1990s is attributable to the changes in pilot operating procedures, as well as the moving of those aircraft to operating areas where severe icing is not a problem, rather than to the modest extension of the deicing boots to 12.5% of the chord.[citation needed]

Three ATR 72s have since crashed because of icing. TransAsia Airways Flight 791 crashed on December 21, 2002, killing both pilots. The cause was attributed to water-droplet size that was beyond Part 25, Appendix C of the FAA design certification.[10]: ii, 131, 156–157, 178 Aero Caribbean Flight 883 crashed on November 4, 2010, killing all 68 people on board.[11] UTair Flight 120 crashed on April 2, 2012, because of a failure to deice the aircraft prior to takeoff, and 33 of the 43 people on board were killed.[12]

A 2020 report from Flight Global described a 2016 icing incident with an ATR 72 involving a Jettime flight for SAS during a domestic Bergen-Alesund service in Norway; nobody was injured in the flight.[13]

Dramatization

[edit]- This crash was featured in the Discovery Channel program The New Detectives in an episode titled "Witness to Terror". (The episode incorrectly indicates the number of victims killed on the flight as 72.)[14]

- The crash was featured in the theatrical production Charlie Victor Romeo.

- The crash was featured in Season 7 of the Canadian documentary series Mayday in an episode titled "Frozen in Flight".[15]

- The crash was briefly mentioned in an episode of Modern Marvels ("Sub Zero") on the History Channel.

See also

[edit]- TransAsia Airways Flight 791 – Another ATR 72 that crashed after a loss of control due to atmospheric icing.

- Comair Flight 3272 – Another aircraft that crashed after a loss of control due to atmospheric icing also during approach 2 years later.

- Voepass Flight 2283 – Another ATR 72 flight suspected to also have suffered from atmospheric icing also during approach in 2024.

- Ice protection system

Notes

[edit]- ^ Including one dual South African-American citizen.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "In-Flight Icing Encounter and Loss of Control, Simmons Airlines, d.b.a. American Eagle Flight 4184, Avions de Transport Regiona (ATR), Model 72-212, N401AM, Roselawn, Indiana, October 31, 1994" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. July 9, 1996. NTSB/AAR-96/01. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "FAA Registry (N401AM)". Federal Aviation Administration.

- ^ Harro, Ranter (October 31, 1994). "ASN Aircraft accident ATR-72-212 N401AM Roselawn, IN". Aviation-safety.net. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- ^ "American Eagle N401AM". airfleets.net. Airfleets aviation.

- ^ "N401AM Simmons Airlines ATR 72". www.planespotters.net. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ^ "Crew and Passengers aboard Flight 4184".

- ^ "In-Flight Icing Encounter, Simmons Airlines, d.b.a. American Eagle Flight 4184, Avions de Transport Regional (ATR) Model 72-212, N401AM, Roselawn, Indiana, October 31, 1994; Volume II: Response of Bureau Enquetes-Accidents to Safety Board's Draft Report" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board via the Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety. May 13, 1996. NTSB/AAR-96/02. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ^ Washburn, Gary (March 2, 1995). "Body Parts At Crash Site Anger Victims' Families, that same year NASA developed the Tailplane Icing program to address pilots to safer reactions to avoid the mistakes that led to the crash of Flight 4184". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 17, 2018. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- ^ a b Boser, Robert (September 2002). "Editor's Reply to Letter to the Editor – Unheeded Warning". AirlineSafety.com. Archived from the original on February 19, 2009. Retrieved December 4, 2007.

- ^ "Inflight icing encounter and crash into the sea, TransAsia Airways Flight 791, ATR72-200, B-22708, 17 kilometers Southwest of Makung City, Phengu Islands, Taiwan, December 21, 2002" (PDF). Aviation Occurrence Report. 1. Taipei, Taiwan: Aviation Safety Council. October 25, 2003. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ Hradecky, Simon. "Crash: Aerocaribbean AT72 near Guasimal on Nov 4th 2010, impacted ground after emergency call". The Aviation Herald. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "Accident ATR 72-201 VP-BYZ, Monday 2 April 2012". asn.flightsafety.org. Retrieved September 16, 2024.

- ^ Kaminski-Morrow, David (September 11, 2020). "Crew's late escape from icing preceded serious ATR 72 upset". Flight Global. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ^ Witness to Terror, June 12, 1997, retrieved February 19, 2020

- ^ Mayday - Air Crash Investigation (S01-S22), retrieved March 16, 2024

External links

[edit]- Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network

- "NTSB AAR-96/01 – NTSB Aircraft Accident Report" (PDF). (3.58 MiB), 340 pages)

- "NTSB AAR-96/02 – Comments of Bureau Enquête-Accidents" (PDF). (4.42 MiB), 341 pages)

- PlaneCrashInfo.Com entry on Flight 4184

- Tv.Com – New Detectives: Witness to Terror (Details Flight 4184 investigation) Archived February 23, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Site for Families and Friends of 4184

- Aviation accidents and incidents in the United States in 1994

- 1994 in Indiana

- Airliner accidents and incidents in Indiana

- Airliner accidents and incidents caused by ice

- 1994 meteorology

- American Airlines accidents and incidents

- Accidents and incidents involving the ATR 72

- Newton County, Indiana

- October 1994 events in the United States

- Aviation accidents and incidents caused by loss of control

- Aviation accidents and incidents in 1994