Bariatric surgery

| Bariatric surgery | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Weight loss surgery |

| MeSH | D050110 |

| Part of a series on |

| Human body weight |

|---|

Bariatric surgery (or weight loss surgery) includes a variety of procedures performed on people who are obese. Long term weight loss through the standard of care procedures (Roux en-Y bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch) is largely achieved by altering gut hormone levels responsible for hunger and satiety, leading to a new hormonal weight set point.[1] Bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment causing weight loss and reducing complications of obesity.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9]

As of October 2022, the American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity (IFSO) recommend bariatric surgery for adults with a body mass index (BMI) >35, regardless of obesity-associated conditions, and recommend considering surgery for people with BMI 30.0-34.9 who have metabolic disease.[10] This is a recent change in guidelines (October 2022), so other guideline-producing organizations and health insurance plans may take time before their guidelines are updated.

Bariatric surgery can have significant health benefits in addition to weight loss, including improvement in cardiovascular risk factors, fatty liver disease, diabetes management, and reduction in mortality. Long-term studies from 2009 show the procedures result in significant long-term loss of weight, recovery from diabetes, improvement in cardiovascular risk factors, and a mortality reduction from 40% to 23%.[11] A meta-analysis in 2021 found that bariatric surgery was associated with 59% and 30% reduction in all-cause mortality among obese adults with or without type 2 diabetes, respectively.[12] This meta-analysis also found that median life-expectancy was 9.3 years longer for obese adults with diabetes who received bariatric surgery as compared to routine (non-surgical) care, whereas the life expectancy gain was 5.1 years longer for obese adults without diabetes.[12] A 2013 National Institute of Health symposium summarizing available evidence found a 29% mortality reduction, a 10-year remission rate of type 2 diabetes of 36%, fewer cardiovascular events, and a lower rate of diabetes-related complications in a long-term, non-randomized, matched intervention 15–20 year follow-up study, the Swedish Obese Subjects Study.[13] The symposium also found similar results from a Utah study using more modern gastric bypass techniques, though the follow-up periods of the Utah studies are only up to seven years. While randomized controlled trials of bariatric surgery exist, they are limited by short follow-up periods. The risk of death in the period following surgery is less than 1 in 1,000.[14]

Physiology

Each type of procedure exerts its effects through at least one of three mechanisms: restricting food intake, decreasing nutrient absorption, or affecting the body's cell signaling pathways. Often, procedures affect several of these mechanisms.

Restricting food intake

This is accomplished by reducing the size of the stomach that is available to hold a meal, (for example, gastric sleeve or stomach folding, see below). Filling the stomach faster enables an individual to feel more full after a smaller meal.

Decreasing nutrient absorption

Some procedures work by reducing the amount of intestine that food passes through. For example, a Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass connects the stomach to a more distal part of the intestine, which reduces the ability of the intestines to absorb nutrients from the food.

Affecting cell signaling pathways

While bariatric procedures may have initially been targeted at reducing intake and absorption, studies have shown additional affects on the hormones that dictate hunger (e.g. ghrelin[15]) and satiety (leptin[16]). This is especially important when considering the durability of weight loss compared to lifestyle changes. While diet and exercise are essential for maintaining a healthy weight and physical fitness, metabolism typically slows as the individual loses weight, a process known as Metabolic Adaptation.[16] Thus, efforts for obese individuals to lose weight often stall, or result in weight re-gain. Bariatric surgery is thought to affect the weight "set point," leading to a more durable weight loss. This is not completely understood, but may involve the cell-signaling pathways and hunger/satiety hormones.

Medical uses

Bariatric surgery has proven to be the most effective obesity treatment option for durable weight loss.[17] Along with this weight reduction, the procedure has significant health benefits ranging from reduced cardiovascular risk factors, remission of Type 2 Diabetes, reduced fatty liver disease, lower incidence and severity of depression syndromes, among others.[15]

Indications

Historically, eligibility for bariatric surgery was defined as a BMI >40, or a BMI >35 with an obesity associated comorbidity—based on the 1991 NIH Consensus Statement. In the three decades that followed, obesity rates have continued to rise, laparoscopic surgical techniques have made the procedure more safe, and high-quality research studies have shown the procedure's effectiveness at improving health across a variety of conditions. Thus, in October 2022, ASMBS/IFSO put forward a revised eligibility criteria, which now includes all adult patients with BMI>35, and those with BMI >30 with metabolic disease.[10]

As of 2019, the American Academy of Pediatrics has recommended bariatric surgery without age-based eligibility limits under the following indications: BMI >35 with severe comorbidity, such as obstructive sleep apnea (Apnea-Hypopnea Index >.5), Type 2 Diabetes mellitus, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, Blount disease, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and idiopathic hypertension or a BMI >40 kg/m2 without comorbidities. Surgery is contraindicated with a medically correctable cause of obesity, substance abuse, concurrent or planned pregnancy, eating disorder, or inability to adhere to postoperative recommendations and mandatory lifestyle changes.[18]

When counseling a patient on bariatric procedures, providers should take an interdisciplinary approach. Psychiatric screening is also critical for determining postoperative success. Patients with a body-mass index of 40 kg/m2 or greater have a 5-fold risk of depression, and half of bariatric surgery candidates are depressed.[19][20] Some people with disordered eating may not be able to follow post-operative dietary guidelines.

Weight loss

In adults, the malabsorptive procedures lead to more weight loss than the restrictive procedures; however, they have a higher risk profile. A 2005 meta-analysis from University of California, Los Angeles, reported the following weight loss at 36 months:[21] Biliopancreatic diversion — 117 Lbs / 53 kg, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) — 90 Lbs / 41 kg, Open — 95 Lbs/ 43 kg, Laparoscopic — 84 Lbs / 38 kg, Vertical banded gastroplasty — 71 Lbs / 32 kg.

In children and teens, evidence for the effectivenss of bariatric surgery is more context-specific. A 2017 meta-analysis found bariatric surgery to be effective for weight loss in adolescents 36 months after the intervention and that additional data was needed to determine whether it is also effective for long-term weight loss in adolescents.[22] According to the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, the comparative evidence base for bariatric surgery in adolescents and young adults was as of 2016 "...limited to a few studies that were narrow in scope and with relatively small sample sizes."[23]

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Type 2 Diabetes is characterized by the body's resistance to the hormone insulin, which results in high blood sugars and a range of complications including increased risk of heart attack, retinopathy, kidney failure, and peripheral neuropathy. Recent studies have shown that patients who have undergone bariatric surgery can often maintain their blood sugars within acceptable levels while discontinuing their diabetes medications.[15][24] This may essentially amount to a 'cure' for diabetes. Prior to the updated guidelines ASMBS/IFSO, international diabetes organizations had recommended considering bariatric surgery in people with a BMI over 30 who have type 2 diabetes and poorly controlled hyperglycemia.[25]

Reduced mortality and morbidity

A meta-analysis of 174,772 participants published in The Lancet in 2021 found that bariatric surgery was associated with 59% and 30% reduction in all-cause mortality among obese adults with or without type 2 diabetes respectively.[12] This meta-analysis also found that median life-expectancy was 9.3 years longer for obese adults with diabetes who received bariatric surgery as compared to routine (non-surgical) care, whereas the life expectancy gain was 5.1 years longer for obese adults without diabetes.[12]

Bariatric surgery in older patients has also been a topic of debate, centered on concerns for safety in this population; the relative benefits and risks in this population is not known.[26]

Fertility and pregnancy

The position of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery as of 2017 was that it was not clearly understood whether medical weight-loss treatments or bariatric surgery had an effect responsiveness to subsequent treatments for infertility in both men and women.[27] Bariatric surgery reduces the risk of gestational diabetes and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in women who later become pregnant but increases the risk of preterm birth.[28]

Mental Health

Among the patients who seek bariatric surgery, pre-operative mental health struggles are common.[29] Some studies have suggested that psychological health can improve after bariatric surgery, due in part to improved body image, self-esteem, and change in self-concept—these findings were also present in pediatric populations.[30] Bariatric surgery has consistently been associated with postoperative decreases in depressive symptoms and reduced severity of symptoms.[30] Importantly, the surgery may not affect everyone the same way, and there are potential adverse effects outlined in the next section.

Adverse effects

Weight loss surgery in adults is associated with relatively large risks and complications, compared to other treatments for obesity.[31][32]

The likelihood of major complications from weight-loss surgery is 4%.[33] "Sleeve gastrectomy had the lowest complication and reoperation rates of the three (main weight-loss surgery) procedures.....The percentage of procedures requiring reoperations due to complications was 15.3 percent for the gastric band, 7.7 percent for gastric bypass and 1.5 percent for sleeve gastrectomy," according to a 2012 study by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.[34] Over a 10-year study while using a common data model to allow for comparisons, 8.94% of patients who received a sleeve gastrectomy required some form of reoperation within 5 years compared to 12.27% of patients who received a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Both of the effects were fewer than those reported with adjustable gastric banding.[35]

As the rate of complications appears to be reduced when the procedure is performed by an experienced surgeon, guidelines recommend that surgery be performed in dedicated or experienced units.[36] It has been observed that the rate of leaks was greater in low volume centres whereas high volume centres showed a lesser leak rate. Leak rates have now globally decreased to a mean of 1-5%.

Postoperative Complications

Laparoscopic bariatric surgery requires a hospital stay of only one or two days. Short-term complications from laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding are reported to be lower than laparoscopic Roux-en-Y surgery, and complications from laparoscopic Roux-en-Y surgery are lower than conventional (open) Roux-en-Y surgery.[11][37][38]

Risks of Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass include Anastomotic Stenosis (narrowing of the intestine where the two segments are rejoined), Marginal ulcers (ulcers near the rejoined segment), internal hernia, small bowel obstruction, kidney stones, and gall stones. Sleeve Gastrectomy also carries a small risk of stenosis, staple line leak, and gastro-esophageal reflux disease (also known as GERD, or heartburn).[15]

In addition to procedure-specific risks, patients also face risks to surgery in general. Pulmonary embolism is another common adverse complication of bariatric surgery.[39] Pulmonary embolism occurs due as a result of deep vein thrombosis, in which blood clots form in the deep veins of the extremities, usually the legs. If not treated, the clot can travel to the heart and then to the lung. This adverse effect is simply prevented by heparin and LMWH, which are both blood thinning medications.[40]

Dumping Syndrome

Dumping syndrome is a condition characterized by quick emptying of the stomach and frequent bowel movements. It is more common following RYGB than SG,[41] and can typically be treated through dietary modification.

Metabolic Bone Disease

Metabolic bone disease manifesting as osteopenia and secondary hyperparathyroidism have been reported after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery due to reduced calcium absorption. The highest concentration of calcium transporters is in the duodenum. Since the ingested food will not pass through the duodenum after a bypass procedure, calcium levels in the blood may decrease, causing secondary hyperparathyroidism, increase in bone turnover, and a decrease in bone mass. Increased risk of fracture has also been linked to bariatric surgery.[42][43]

Cholelithiasis (Gallstones)

Rapid weight loss after obesity surgery can contribute to the development of gallstones by increasing the lithogenicity of bile. Estimates for prevalence of symptomatic cholecystitis after Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass range from 3-13%.[15] Cholelithiasis can be managed with a removal of the gallbladder (Cholecystectomy).

Renal Effects

Adverse effects on the kidneys have been studied. Hyperoxaluria that can potentially lead to oxalate nephropathy and irreversible renal failure is the most significant abnormality seen on urine chemistry studies. Rhabdomyolysis leading to acute kidney injury, and impaired renal handling of acid and base has been reported after bypass surgery.[44] Additionally, Nephrolithiasis (kidney stones) are common after Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass, with estimates of prevalence ranging from 7-11%.[15]

Nutritional Deficiencies

Deficiencies of micronutrients like iron, vitamin B12, fat soluble vitamins, thiamine, and folate are especially common after malabsorptive bariatric procedures. Seizures due to hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia have been reported. Inappropriate insulin secretion secondary to islet cell hyperplasia, called pancreatic nesidioblastosis, might explain this syndrome.[45][46][47]

Mental Health

Though many benefits to mental health are described above, there are several potential adverse effects that should be discussed. Alcohol problems have been reported to be more common in patients who have undergone gastric bypass surgery.[48] Of note, patients who receive an RYGB may reach a higher peak alcohol concentration more quickly, due to changes in their metabolism.[30] In addition, Self-harm behaviors and suicide appear to be increased in people with mental health issues in the five years after bariatric surgery had been done.[49]

Types

Bariatric procedures can be grouped in three main categories: blocking (reduce the absorption of nutrients), restricting (decrease the size of the gut and therefore the amount of food that can pass through), and mixed which are understood to work by altering gut hormone levels responsible for hunger and satiety.[50] However, this distinction might be less clear-cut than it may seem. For instance, while Sleeve Gastrectomy (discussed below) was initially thought to work simply by reducing the size of the stomach, research has begun to elucidate changes in gut hormone signaling as well. The two most frequently performed procedures are Sleeve Gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (also galled gastric bypass), with Sleeve Gastrectomy accounting for more than half of all procedures since 2014.[15]

Most Common

Sleeve gastrectomy

Sleeve gastrectomy, or gastric sleeve, is a surgical weight-loss procedure in which the stomach is reduced to about 15% of its original size, by the surgical removal of a large portion of the stomach, following the major curve. The open edges are then attached together (typically with surgical staples, sutures, or both) to leave the stomach shaped more like a tube, or a sleeve, with a banana shape. While this procedure was initially thought to work only by reducing the size of the stomach, recent research has also shown that there are changes in gut signaling hormones.[51] The procedure is performed laparoscopically and is not reversible. It has been found to produce a weight loss comparable to that of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. While it is not as effective at treating GERD or Type 2 Diabetes as RYGB, it has less risk of side effects like ulcers or intestinal strictures (narrowing of the gut).[15]

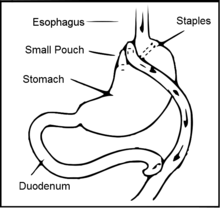

Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery (RYGB)

Main article: Gastric bypass surgery

The Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is designed to alter the gut hormones that control hunger and satiety. While the complete hormonal mechanisms are still being understood, it is now widely accepted that this is a hormonal procedure in addition to restriction and malabsorption properties.[1] Gastric bypass is a permanent procedure that helps patients reset hunger and satiety by altering stomach and small intestine handle the food that is eaten to achieve and maintain weight loss goals. After the surgery, the stomach will be smaller and there will be an increase in baseline satiety hormones, to help the patient will feel full with less food.[52]

The gastric bypass had been the most commonly performed operation for weight loss in the United States, and approximately 140,000 gastric bypass procedures were performed in 2005. Its market share has decreased, and since 2013, Sleeve Gastrectomy has overtaken RYGB as the most common bariatric procedure.[15]

A factor in the success of any bariatric surgery is strict post-surgical adherence to a healthy pattern of eating. One common side effect of bariatric surgery that is commonly reported with RYGB is Dumping Syndrome, in which food moves too quickly from the stomach to the small intestine. This can usually be treated through dietary changes.

Biliopancreatic Diversion with Duodenal Switch (BPD/DS)

Main Article: biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch

A slightly less common bariatric procedure, accounting for less than 1% of all bariatric procedures in 2016. The part of the stomach along its greater curve is resected and the remaining stomach is "tubulized" with a residual volume of about 150 ml. This volume reduction provides the food intake restriction component of this operation. This type of gastric resection is anatomically and functionally irreversible. The stomach is then disconnected from the duodenum and connected to the distal part of the small intestine. The duodenum and the upper part of the small intestine are reattached to the rest at about 75–100 cm from the colon.[citation needed]. Like the Roux en Y Bypass, it is now understood that its results are largely due to a significant alteration in gut hormones that control hunger and satiety, in addition to its restriction and malabsorption properties. The addition of the sleeve gastrectomy, causes further gut hormone set- point alterations by reducing levels of the hunger hormone, Ghrelin. Compared to the Sleeve Gastrectomy and Rou-en-Y Gastric Bypass, BPD/DS produces the best results in terms of durable weight loss and resolution of Type 2 Diabetes.

Other procedures

Vertical banded gastroplasty

In the vertical banded gastroplasty, also called the Mason procedure or stomach stapling, a part of the stomach is permanently stapled to create a smaller pre-stomach pouch, which serves as the new stomach.[citation needed]

Stomach folding

Basically, the procedure can best be understood as a version of the more popular gastric sleeve or gastrectomy surgery where a sleeve is created by suturing rather than removing stomach tissue thus preserving its natural nutrient absorption capabilities. Gastric plication significantly reduces the volume of the patient's stomach, so smaller amounts of food provide a feeling of satiety.[citation needed] The procedure is producing some significant results that were published in a recent study in Bariatric Times and are based on post-operative outcomes for 66 patients (44 female) who had the gastric sleeve plication procedure between January 2007 and March 2010. Mean patient age was 34, with a mean BMI of 35. Follow-up visits for the assessment of safety and weight loss were scheduled at regular intervals in the postoperative period. No major complications were reported among the 66 patients. Weight loss outcomes are comparable to gastric bypass.

The study describes gastric sleeve plication (also referred to as gastric imbrication or laparoscopic greater curvature plication) as a restrictive technique that eliminates the complications associated with adjustable gastric banding and vertical sleeve gastrectomy—it does this by creating restriction without the use of implants and without gastric resection (cutting) and staples.

Implants and Devices

Adjustable gastric band

The restriction of the stomach also can be created using a silicone band, which can be adjusted by addition or removal of saline through a port placed just under the skin. This operation can be performed laparoscopically, and is commonly referred to as a "lap band". Weight loss is predominantly due to the restriction of nutrient intake that is created by the small gastric pouch and the narrow outlet.[53] It is considered somewhat of a safe surgical procedure, with a mortality rate of 0.05%.[54]

Intragastric balloon

Intragastric balloon involves placing a deflated balloon into the stomach, and then filling it to decrease the amount of gastric space. The balloon can be left in the stomach for a maximum of 6 months and results in an average weight loss of 5–9 BMI over half a year.[55] The intragastric balloon is approved in Australia, Canada, Mexico, India, United States (received FDA approval in 2015) and several European and South American countries.[56][57] The intragastric balloon may be used prior to another bariatric surgery in order to assist the patient to reach a weight which is suitable for surgery, further it can also be used on several occasions if necessary.[58]

There are three cost categories for the intragastric balloon: pre-operative (e.g. professional fees, lab work and testing), the procedure itself (e.g. surgeon, surgical assistant, anesthesia and hospital fees) and post-operative (e.g. follow-up physician office visits, vitamins and supplements).

Quoted costs for the intragastric balloon are surgeon-specific and vary by region. Average quoted costs by region are as follows (provided in United States Dollars for comparison): Australia: US$4,178; Canada: US$8,250; Mexico: US$5,800; United Kingdom: US$6,195; United States: US$8,150.[59]

Endoluminal sleeve

This is a flexible tube inserted, through the mouth and stomach, into the upper small intestine. The purpose is to block absorption of certain foods/calories. It does not involve actual cutting and so is designed to lower risks from infection etc.[60] however the results were not conclusive and the device had issues with migration and slipping. A study recently done in the Netherlands found a decrease of 5.5 BMI points in 3 months with an endoluminal sleeve.

Implantable gastric stimulation

This procedure where a device similar to a heart pacemaker that is implanted by a surgeon, with the electrical leads stimulating the external surface of the stomach, is being studied in the USA. Electrical stimulation is thought to modify the activity of the enteric nervous system of the stomach, which is interpreted by the brain to give a sense of satiety, or fullness. Early evidence suggests that it is less effective than other forms of bariatric surgery.[61]

Historical Procedures (rarely performed)

Biliopancreatic diversion

This operation is termed biliopancreatic diversion (BPD) or the Scopinaro procedure. The original form of this procedure is now rarely performed and has been replaced with a modification known as biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS), or simply duodenal switch (DS). Part of the stomach is resected, creating a smaller stomach (however the patient can eat a free diet as there is no restrictive component). The distal part of the small intestine is then connected to the pouch, bypassing the duodenum and jejunum.

In around 2% of patients there is severe malabsorption and nutritional deficiency that requires restoration of the normal absorption. The malabsorptive effect of BPD is so potent that, as in most restrictive procedures, those who undergo the procedure must take vitamin and dietary minerals above and beyond that of the normal population.[62] Without these supplements, there is risk of serious deficiency diseases such as anemia and osteoporosis.[62]

Because gallstones are a common complication of the rapid weight loss following any type of bariatric surgery, some surgeons remove the gallbladder as a preventive measure during BPD. Others prefer to prescribe medications to reduce the risk of post-operative gallstones.[63]

Far fewer surgeons perform BPD compared to other weight loss surgeries, in part because of the need for long-term nutritional follow-up and monitoring of BPD patients.[citation needed]

Jejunoileal bypass

This procedure is no longer performed. It was a surgical weight-loss procedure performed for the relief of morbid obesity from the 1950s through the 1970s in which all but 30 cm (12 in) to 45 cm (18 in) of the small bowel was detached and set to the side.

Post-Procedure Follow-up

In many institutions, patients are followed closely both before and after a procedure. The care team may also include people in a variety of disciplines, including social work, dietitians, and medical weight management specialists. Follow up post-op is typically focused on helping avoid complications, and tracking patients' progress toward their weight goals.

Dietary Recommendations

Diet restrictions after recovery from surgery depend in part on the type of surgery. In general, immediately after bariatric surgery, the patient is restricted to a clear liquid diet, which includes foods such as clear broth, diluted fruit juices or sugar-free drinks and gelatin desserts. This diet is continued until the gastrointestinal tract begins to recover. The next stage provides a blended or pureed sugar-free diet for at least two weeks. This may consist of high protein, liquid or soft foods such as protein shakes, soft meats, and dairy products. Foods high in carbohydrates are usually avoided when possible during the initial weight loss period. Post-surgery, overeating is curbed because exceeding the capacity of the stomach causes nausea and vomiting.

In the long term, many patients will need to take a daily multivitamin pill for life to compensate for reduced absorption of essential nutrients.[64] Because patients cannot eat a large quantity of food, physicians typically recommend a diet that is relatively high in protein and low in fats and alcohol.

Fluid recommendations

It is very common, within the first-month post-surgery, for a patient to undergo volume depletion and dehydration. Patients have difficulty drinking the appropriate amount of fluids as they adapt to their new gastric volume. Additionally, limitations on oral fluid intake, reduced calorie intake, and a higher incidence of vomiting and diarrhea all contribute to dehydration.[65]

Family Planning

In general, patients are advised to avoid pregnancy for 12–24 months after a bariatric surgery.[66] This waiting period is intended to reduce the possibility of Intrauterine Growth Restriction or nutrient deficiency, since the bariatric surgery patient will likely undergo significant weight loss and changes in metabolism. In the long run, however, the rates of many adverse maternal and fetal outcomes are reduced for obese mothers following bariatric surgery.[66]

Cosmetic body contouring

After a person successfully loses weight following bariatric surgery, they are usually left with excess skin. These can be addressed in a series of plastic surgery procedures sometimes called body contouring in which the skin flaps are removed. Targeted areas include the arms, buttocks and thighs, abdomen, and breasts.[67] These procedures are taken slowly, step by step, and from beginning to end often takes three years.[68]

Economic Implications

The cost of healthcare in the United States is increasing, and obesity rates are likely to be playing a role. Per the CDC, approximately 41.9% of US adults are obese (as measured from 2017-2020), a rate that has increased significantly from a level of 30.5% in 1999-2000.[69] Obesity-related illnesses account for 14.3% of US healthcare spending, and also result in significant losses to the economy through decreased productivity.[15]

Bariatric surgery is expensive, with average cost estimates ranging from $11,500 to $26,000, however, this cost is estimated to be recovered within 2–4 years due to decreased healthcare spending, gains in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and increased productivity.[15] Cohort modeling has found that Bariatric Surgery results in a net QALY gain of 4.2, and is cost-saving from a societal perspective.[70] Even by the previous BMI criteria, a study had found that more than 32 million people may have been eligible for bariatric surgery in 2016—nearly triple the 1993 amount.[71] Importantly, only ~1% of eligible patients receives bariatric surgery.[72][15]

Considerations in adolescent patients

As childhood obesity has more than doubled over recent years and more than tripled in adolescents (according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), bariatric surgery for youth has become increasingly common across the various types of procedures.[73][74][75] Some worry that a decline in life expectancy might occur from the increasing levels of obesity,[76] so providing youth with proper care may help prevent the serious medical complications caused by obesity and its related diseases. Difficulties and ethical issues arise when making decisions related to obesity treatments for those that are too young or otherwise unable to give consent without adult guidance.[74]

Children and adolescents are still developing, both physically and mentally. This makes it difficult for them to make an informed decision and give consent to move forward with a treatment.[77][needs update] These patients may also be experiencing severe depression or other psychological disorders related to their obesity that make understanding the information very difficult.[74][78]

History

Open weight loss surgery began slowly in the 1950s with the intestinal bypass. It involved anastomosis of the upper and lower intestine, which bypasses a large amount of the absorptive circuit, which caused weight loss purely by the malabsorption of food. Later Drs. J. Howard Payne, Lorent T. DeWind and Robert R. Commons developed in 1963 the Jejuno-colic Shunt, which connected the upper small intestine to the colon. The laboratory research leading to gastric bypass did not begin until 1965 when Dr. Edward E. Mason (b. 1920) and Dr. Chikashi Ito (1930–2013) at the University of Iowa developed the original gastric bypass for weight reduction which led to fewer complications than the intestinal bypass and for this reason Mason is known as the "father of obesity surgery".[79]

See also

References

- ^ a b Pucci, A.; Batterham, R. L. (2019). "Mechanisms underlying the weight loss effects of RYGB and SG: similar, yet different". Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 42 (2): 117–128. doi:10.1007/s40618-018-0892-2. ISSN 0391-4097. PMC 6394763. PMID 29730732.

- ^ Müller, Timo D.; Blüher, Matthias; Tschöp, Matthias H.; DiMarchi, Richard D. (March 2022). "Anti-obesity drug discovery: advances and challenges". Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 21 (3): 201–223. doi:10.1038/s41573-021-00337-8. ISSN 1474-1784. PMC 8609996. PMID 34815532.

Bariatric surgery represents the most effective approach to weight loss...

- ^ Bettini, Silvia; Belligoli, Anna; Fabris, Roberto; Busetto, Luca (2020). "Diet approach before and after bariatric surgery". Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. 21 (3): 297–306. doi:10.1007/s11154-020-09571-8. ISSN 1573-2606. PMC 7455579. PMID 32734395.

Bariatric surgery (BS) is today the most effective therapy for inducing long-term weight loss and for reducing comorbidity burden and mortality in patients with severe obesity.

- ^ Zarshenas, Nazy; Tapsell, Linda Clare; Neale, Elizabeth Phillipa; Batterham, Marijka; Talbot, Michael Leonard (1 May 2020). "The Relationship Between Bariatric Surgery and Diet Quality: a Systematic Review". Obesity Surgery. 30 (5): 1768–1792. doi:10.1007/s11695-020-04392-9. ISSN 1708-0428. PMID 31940138. S2CID 210195296.

Bariatric surgery is currently the most effective treatment for morbid obesity.

- ^ Athanasiadis, Dimitrios I.; Martin, Anna; Kapsampelis, Panagiotis; Monfared, Sara; Stefanidis, Dimitrios (1 August 2021). "Factors associated with weight regain post-bariatric surgery: a systematic review". Surgical Endoscopy. 35 (8): 4069–4084. doi:10.1007/s00464-021-08329-w. ISSN 1432-2218. PMID 33650001. S2CID 232083997.

Bariatric surgery is the most effective intervention for sustained weight loss of morbidly obese patients, but WR remains a concern.

- ^ Dang, Jerry T.; Lee, Jeremy K. H.; Kung, Janice Y.; Switzer, Noah J.; Karmali, Shahzeer; Birch, Daniel W. (March 2020). "The Effect of Bariatric Surgery on Migraines: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Obesity Surgery. 30 (3): 1061–1067. doi:10.1007/s11695-019-04290-9. PMID 31786719. S2CID 208496819.

Given that bariatric surgery is the most effective intervention for obesity and obesity-related comorbidities, there is potential for bariatric surgery to improve migraine symptoms.

- ^ Hedjoudje, Abdellah; Abu Dayyeh, Barham K.; Cheskin, Lawrence J.; Adam, Atif; Neto, Manoel Galvão; Badurdeen, Dilhana; Morales, Javier Graus; Sartoretto, Adrian; Nava, Gontrand Lopez; Vargas, Eric; Sui, Zhixian; Fayad, Lea; Farha, Jad; Khashab, Mouen A.; Kalloo, Anthony N.; Alqahtani, Aayed R.; Thompson, Christopher C.; Kumbhari, Vivek (May 2020). "Efficacy and Safety of Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 18 (5): 1043–1053.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.022. PMID 31442601. S2CID 201632114.

Bariatric surgery is the most successful treatment for obesity.

- ^ Cerón-Solano, Giovanni; Zepeda, Rossana C.; Romero Lozano, José Gilberto; Roldán-Roldán, Gabriel; Morin, Jean-Pascal (2021). "Bariatric surgery and alcohol and substance abuse disorder: A systematic review". Cirugía Española (English Edition). 99 (9): 635–647. doi:10.1016/j.cireng.2021.10.004. PMID 34690075. S2CID 239519223.

Bariatric surgery is the best treatment for obesity and its complications.

- ^ Snoek, Katinka M; Steegers-Theunissen, Régine P M; Hazebroek, Eric J; Willemsen, Sten P; Galjaard, Sander; Laven, Joop S E; Schoenmakers, Sam (18 October 2021). "The effects of bariatric surgery on periconception maternal health: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction Update. 27 (6): 1030–1055. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmab022. PMC 8542997. PMID 34387675.

Worldwide, the prevalence of obesity in women of reproductive age is increasing. Bariatric surgery is currently viewed as the most effective, long-term solution for this problem.

- ^ a b "After 30 Years — New Guidelines For Weight-Loss Surgery". American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. 2022-10-21. Retrieved 2022-11-07.

- ^ a b Robinson MK (July 2009). "Editorial: Surgical treatment of obesity—weighing the facts". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (5): 520–1. doi:10.1056/NEJMe0904837. PMID 19641209.

- ^ a b c d Syn, Nicholas L.; Cummings, David E.; Wang, Louis Z.; Lin, Daryl J.; Zhao, Joseph J.; Loh, Marie; Koh, Zong Jie; Chew, Claire Alexandra; Loo, Ying Ern; Tai, Bee Choo; Kim, Guowei (2021-05-15). "Association of metabolic-bariatric surgery with long-term survival in adults with and without diabetes: a one-stage meta-analysis of matched cohort and prospective controlled studies with 174 772 participants". Lancet. 397 (10287): 1830–1841. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00591-2. ISSN 1474-547X. PMID 33965067. S2CID 234345414.

- ^ Courcoulas AP, Yanovski SZ, Bonds D, Eggerman TL, Horlick M, Staten MA, Arterburn DE (December 2014). "Long-term outcomes of bariatric surgery: a National Institutes of Health symposium". JAMA Surgery. 149 (12): 1323–9. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2014.2440. PMC 5570469. PMID 25271405.

- ^ Robertson, A. G. N.; Wiggins, T.; Robertson, F. P.; Huppler, L.; Doleman, B.; Harrison, E. M.; Hollyman, M.; Welbourn, R. (19 August 2021). "Perioperative mortality in bariatric surgery: meta-analysis". The British Journal of Surgery. 108 (8): 892–897. doi:10.1093/bjs/znab245. PMID 34297806.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l English, Wayne J.; Williams, D. Brandon (July 2018). "Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery: An Effective Treatment Option for Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease". Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 61 (2): 253–269. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2018.06.003. ISSN 1873-1740. PMID 29953878. S2CID 49592181.

- ^ a b Knuth, Nicolas D.; Johannsen, Darcy L.; Tamboli, Robyn A.; Marks-Shulman, Pamela A.; Huizenga, Robert; Chen, Kong Y.; Abumrad, Naji N.; Ravussin, Eric; Hall, Kevin D. (December 2014). "Metabolic adaptation following massive weight loss is related to the degree of energy imbalance and changes in circulating leptin". Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.). 22 (12): 2563–2569. doi:10.1002/oby.20900. ISSN 1930-739X. PMC 4236233. PMID 25236175.

- ^ Maciejewski, Matthew L.; Arterburn, David E.; Van Scoyoc, Lynn; Smith, Valerie A.; Yancy, William S.; Weidenbacher, Hollis J.; Livingston, Edward H.; Olsen, Maren K. (2016-11-01). "Bariatric Surgery and Long-term Durability of Weight Loss". JAMA Surgery. 151 (11): 1046–1055. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2016.2317. ISSN 2168-6254. PMC 5112115. PMID 27579793.

- ^ Armstrong, Sarah C.; Bolling, Christopher F.; Michalsky, Marc P.; Reichard, Kirk W.; SECTION ON OBESITY, SECTION ON SURGERY; Haemer, Matthew Allen; Muth, Natalie Digate; Rausch, John Conrad; Rogers, Victoria Weeks; Heiss, Kurt F.; Besner, Gail Ellen (2019-12-01). "Pediatric Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery: Evidence, Barriers, and Best Practices". Pediatrics. 144 (6): e20193223. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-3223. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 31656225. S2CID 204947687.

- ^ Yen YC, Huang CK, Tai CM (September 2014). "Psychiatric aspects of bariatric surgery". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 27 (5): 374–9. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000085. PMC 4162326. PMID 25036421.

- ^ Lin HY, Huang CK, Tai CM, Lin HY, Kao YH, Tsai CC, Hsuan CF, Lee SL, Chi SC, Yen YC (January 2013). "Psychiatric disorders of patients seeking obesity treatment". BMC Psychiatry. 13: 1. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-13-1. PMC 3543713. PMID 23281653.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Maggard MA, Shugarman LR, Suttorp M, Maglione M, Sugerman HJ, Sugarman HJ, Livingston EH, Nguyen NT, Li Z, Mojica WA, Hilton L, Rhodes S, Morton SC, Shekelle PG (April 2005). "Meta-analysis: surgical treatment of obesity". Annals of Internal Medicine. 142 (7): 547–59. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00013. PMID 15809466.

- ^ Pedroso FE, Angriman F, Endo A, Dasenbrock H, Storino A, Castillo R, Watkins AA, Castillo-Angeles M, Goodman JE, Zitsman JL (March 2018). "Weight loss after bariatric surgery in obese adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 14 (3): 413–422. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2017.10.003. PMID 29248351.

- ^ Bariatric Surgery for Adolescents and Young Adults: A Review of Comparative Clinical Effectiveness, Cost-Effectiveness, and Evidence-Based Guidelines. CADTH Rapid Response Reports. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. 2016. PMID 27831668.

- ^ Schauer, Philip R.; Bhatt, Deepak L.; Kirwan, John P.; Wolski, Kathy; Aminian, Ali; Brethauer, Stacy A.; Navaneethan, Sankar D.; Singh, Rishi P.; Pothier, Claire E.; Nissen, Steven E.; Kashyap, Sangeeta R.; STAMPEDE Investigators (2017-02-16). "Bariatric Surgery versus Intensive Medical Therapy for Diabetes - 5-Year Outcomes". The New England Journal of Medicine. 376 (7): 641–651. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1600869. ISSN 1533-4406. PMC 5451258. PMID 28199805.

- ^ Stenberg, Erik; dos Reis Falcão, Luiz Fernando; O’Kane, Mary; Liem, Ronald; Pournaras, Dimitri J.; Salminen, Paulina; Urman, Richard D.; Wadhwa, Anupama; Gustafsson, Ulf O.; Thorell, Anders (2022). "Guidelines for Perioperative Care in Bariatric Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society Recommendations: A 2021 Update". World Journal of Surgery. 46 (4): 729–751. doi:10.1007/s00268-021-06394-9. PMC 8885505. PMID 34984504.

- ^ Colquitt JL; et al. (Aug 2014). "Surgery for weight loss in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 (8): CD003641. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003641.pub4. PMC 9028049. PMID 25105982.

- ^ Kominiarek MA, Jungheim ES, Hoeger KM, Rogers AM, Kahan S, Kim JJ (May 2017). "American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery position statement on the impact of obesity and obesity treatment on fertility and fertility therapy Endorsed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Obesity Society". Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 13 (5): 750–757. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2017.02.006. PMID 28416185.

- ^ Kwong W, Tomlinson G, Feig DS (June 2018). "Maternal and neonatal outcomes after bariatric surgery; a systematic review and meta-analysis: do the benefits outweigh the risks?". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 218 (6): 573–580. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.02.003. PMID 29454871. S2CID 3837276.

- ^ Morledge, Michael D.; Pories, Walter J. (April 2020). "Mental Health in Bariatric Surgery: Selection, Access, and Outcomes". Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.). 28 (4): 689–695. doi:10.1002/oby.22752. ISSN 1930-739X. PMID 32202073. S2CID 214618061.

- ^ a b c Kubik JF, Gill RS, Laffin M, Karmali S (2013). "The impact of bariatric surgery on psychological health". Journal of Obesity. 2013: 1–5. doi:10.1155/2013/837989. PMC 3625597. PMID 23606952.

- ^ Beaulac J, Sandre D (May 2017). "Critical review of bariatric surgery, medically supervised diets, and behavioural interventions for weight management in adults". Perspectives in Public Health. 137 (3): 162–172. doi:10.1177/1757913916653425. PMID 27354536. S2CID 3853658.

- ^ Torpy JM (2005). "Bariatric Surgery". JAMA. 294 (15): 1986. doi:10.1001/jama.294.15.1986. PMID 16234505. Retrieved 10 Sep 2020.

- ^ Flum DR, Belle SH, King WC, Wahed AS, Berk P, Chapman W, Pories W, Courcoulas A, McCloskey C, Mitchell J, Patterson E, Pomp A, Staten MA, Yanovski SZ, Thirlby R, Wolfe B (July 2009). "Perioperative safety in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (5): 445–54. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0901836. PMC 2854565. PMID 19641201.

- ^ "Studies Weigh in on Safety and Effectiveness of Newer Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery Procedure - American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery". American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. 2012-06-20.

- ^ Courcoulas, Anita; Coley, R. Yates; Clark, Jeanne M.; McBride, Corrigan L.; Cirelli, Elizabeth; McTigue, Kathleen; Arterburn, David; Coleman, Karen J.; Wellman, Robert; Anau, Jane; Toh, Sengwee (2020-03-01). "Interventions and Operations 5 Years After Bariatric Surgery in a Cohort From the US National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network Bariatric Study". JAMA Surgery. 155 (3): 194–204. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2019.5470. ISSN 2168-6254. PMC 6990709. PMID 31940024.

- ^ Snow V, Barry P, Fitterman N, Qaseem A, Weiss K (April 2005). "Pharmacologic and surgical management of obesity in primary care: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 142 (7): 525–31. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00011. PMID 15809464.

- ^ Flum DR, Belle SH, King WC, Wahed AS, Berk P, Chapman W, Pories W, Courcoulas A, McCloskey C, Mitchell J, Patterson E, Pomp A, Staten MA, Yanovski SZ, Thirlby R, Wolfe B (July 2009). "Perioperative safety in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (5): 445–54. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0901836. PMC 2854565. PMID 19641201.

- ^ Nguyen NT, Silver M, Robinson M, Needleman B, Hartley G, Cooney R, Catalano R, Dostal J, Sama D, Blankenship J, Burg K, Stemmer E, Wilson SE (May 2006). "Result of a national audit of bariatric surgery performed at academic centers: a 2004 University HealthSystem Consortium Benchmarking Project". Archives of Surgery. 141 (5): 445–9, discussion 449–50. doi:10.1001/archsurg.141.5.445. PMID 16702515.

- ^ Sapala, James A.; Wood, Michael H.; Schuhknecht, Michael P.; Sapala, M. Andrew (2003-12-01). "Fatal Pulmonary Embolism after Bariatric Operations for Morbid Obesity: A 24-Year Retrospective Analysis". Obesity Surgery. 13 (6): 819–825. doi:10.1381/096089203322618588. ISSN 1708-0428. PMID 14738663. S2CID 20798423.

- ^ Scholten, Donald J.; Hoedema, Rebecca M.; Scholten, Sarah E. (2002-02-01). "A Comparison of Two Different Prophylactic Dose Regimens of Low Molecular Weight Heparin in Bariatric Surgery". Obesity Surgery. 12 (1): 19–24. doi:10.1381/096089202321144522. ISSN 1708-0428. PMID 11868291. S2CID 38002757.

- ^ Fischer, Lars; Wekerle, Anna-Laura; Bruckner, Thomas; Wegener, Inga; Diener, Markus K.; Frankenberg, Moritz V.; Gärtner, Daniel; Schön, Michael R.; Raggi, Matthias C.; Tanay, Emre; Brydniak, Rainer; Runkel, Norbert; Attenberger, Corinna; Son, Min-Seop; Türler, Andreas (2015-07-18). "BariSurg trial: Sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in obese patients with BMI 35-60 kg/m(2) - a multi-centre randomized patient and observer blind non-inferiority trial". BMC Surgery. 15: 87. doi:10.1186/s12893-015-0072-7. ISSN 1471-2482. PMC 4506636. PMID 26187377.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Bariatric Surgery Linked to Increased Fracture Risk". Science Daily. Retrieved 2011-06-05.

- ^ Ahlin S; et al. (May 2020). "Fracture risk after three bariatric surgery procedures in Swedish obese subjects: up to 26 years follow-up of a controlled intervention study". J. Intern. Med. 287 (5): 546–557. doi:10.1111/joim.13020. PMID 32128923. S2CID 212408565.

- ^ "Bariatric Surgery: A Detailed Overview". bariatricguide.org. Bariatric Surgery Information Guide. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ Chauhan V, Vaid M, Gupta M, Kalanuria A, Parashar A (August 2010). "Metabolic, renal, and nutritional consequences of bariatric surgery: implications for the clinician". Southern Medical Journal. 103 (8): 775–83, quiz 784–5. doi:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181e6cc3f. PMID 20622731.

- ^ "Reproductive and Other Health Considerations for Women Undergoing Bariatric Surgery". Journal Watch.

- ^ Miller K (2008). Comparison of Nutritional Deficiencies and Complications following Vertical Sleeve Gastrectomy, Roux-en-y Gastric Bypass, and Biliopancreatic Diversion with Duodenal Switch (Ph.D. thesis). Bowling Green State University. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ^ Svensson PA; et al. (Dec 2013). "Alcohol consumption and alcohol problems after bariatric surgery in the Swedish obese subjects study". Obesity. 21 (12): 2444–2451. doi:10.1002/oby.20397. PMID 23520203. S2CID 30688487.

- ^ Bhatti JA, Nathens AB, Thiruchelvam D, Grantcharov T, Goldstein BI, Redelmeier DA (March 2016). "Self-harm Emergencies After Bariatric Surgery: A Population-Based Cohort Study". JAMA Surgery. 151 (3): 226–32. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.3414. PMID 26444444.

- ^ Abell TL, Minocha A (April 2006). "Gastrointestinal complications of bariatric surgery: diagnosis and therapy". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 331 (4): 214–8. doi:10.1097/00000441-200604000-00008. PMID 16617237. S2CID 25920218.

- ^ Cornejo-Pareja, Isabel; Clemente-Postigo, Mercedes; Tinahones, Francisco J. (2019-09-19). "Metabolic and Endocrine Consequences of Bariatric Surgery". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 10: 626. doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00626. ISSN 1664-2392. PMC 6761298. PMID 31608009.

- ^ Pucci, A.; Batterham, R. L. (2019). "Mechanisms underlying the weight loss effects of RYGB and SG: similar, yet different". Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 42 (2): 117–128. doi:10.1007/s40618-018-0892-2. ISSN 0391-4097. PMC 6394763. PMID 29730732.

- ^ Shikora SA, Kim JJ, Tarnoff ME (February 2007). "Nutrition and gastrointestinal complications of bariatric surgery". Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 22 (1): 29–40. doi:10.1177/011542650702200129. PMID 17242452.

- ^ Freitas A, Sweeney JF (2010). "20. Bariatric Surgery". In B. Banerjee (ed.). Nutritional Management of Digestive Disorders. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. pp. 327–342.

- ^ Mathus-Vliegen EM (2008). "Intragastric balloon treatment for obesity: what does it really offer?". Digestive Diseases. 26 (1): 40–4. doi:10.1159/000109385. PMID 18600014. S2CID 207744056.

- ^ Rosenthal E (January 3, 2006). "Europeans Find Extra Options for Staying Slim". The New York Times. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ "FDA approves non-surgical temporary balloon device to treat obesity". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. July 30, 2015. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ "Gastric Balloon | the Health Clinic UK". Archived from the original on 2010-12-01. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

- ^ Gastric Balloon Surgery: Complete Patient Guide (Annual Gastric Balloon Cost Survey), Bariatric Surgery Source, retrieved 22 September 2015

- ^ "Intestinal Sleeve May Improve Glycemic Control". medpagetoday.com. 16 November 2009.

- ^ Pardo JV, Sheikh SA, Kuskowski MA, Surerus-Johnson C, Hagen MC, Lee JT, Rittberg BR, Adson DE (November 2007). "Weight loss during chronic, cervical vagus nerve stimulation in depressed patients with obesity: an observation". International Journal of Obesity. 31 (11): 1756–9. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0803666. PMC 2365729. PMID 17563762.

- ^ a b Heber, David; Greenway, Frank L.; Kaplan, Lee M.; Livingston, Edward; Salvador, Javier; Still, Christopher; Endocrine Society (2010). "Endocrine and nutritional management of the post-bariatric surgery patient: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 95 (11): 4823–4843. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-2128. ISSN 1945-7197. PMID 21051578.

- ^ Sucandy, Iswanto; Abulfaraj, Moaz; Naglak, Mary; Antanavicius, Gintaras (2016). "Risk of Biliary Events After Selective Cholecystectomy During Biliopancreatic Diversion with Duodenal Switch". Obesity Surgery. 26 (3): 531–537. doi:10.1007/s11695-015-1786-4. ISSN 1708-0428. PMID 26156307. S2CID 31588556.

- ^ Tucker ON, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ (May 2007). "Nutritional consequences of weight-loss surgery". The Medical Clinics of North America. 91 (3): 499–514, xii. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2007.01.006. PMID 17509392.

- ^ Petering R, Webb CW (2009). "Exercise, fluid, and nutrition recommendations for the postgastric bypass exerciser". Current Sports Medicine Reports. 8 (2): 92–7. doi:10.1249/JSR.0b013e31819e2cd6. PMID 19276910. S2CID 7007125.

- ^ a b Narayanan, Ram Prakash; Syed, Akheel A. (October 2016). "Pregnancy Following Bariatric Surgery-Medical Complications and Management". Obesity Surgery. 26 (10): 2523–2529. doi:10.1007/s11695-016-2294-x. ISSN 1708-0428. PMC 5018021. PMID 27488114.

- ^ Chandawarkar RY (2006). "Body contouring following massive weight loss resulting from bariatric surgery". Advances in Psychosomatic Medicine. 27: 61–72. doi:10.1159/000090964. ISBN 3-8055-8028-2. PMID 16418543.

- ^ Chandawarkar RY (2006). "Body contouring following massive weight loss resulting from bariatric surgery". Advances in Psychosomatic Medicine. 27: 61–72. doi:10.1159/000090964. ISBN 3-8055-8028-2. PMID 16418543.

- ^ CDC (2022-07-20). "Obesity is a Common, Serious, and Costly Disease". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2022-11-07.

- ^ Lester, Erica L. W.; Padwal, Raj S.; Birch, Daniel W.; Sharma, Arya M.; So, Helen; Ye, Feng; Klarenbach, Scott W. (April 2021). "The real-world cost-effectiveness of bariatric surgery for the treatment of severe obesity: a cost-utility analysis". CMAJ Open. 9 (2): E673–E679. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20200188. ISSN 2291-0026. PMC 8248561. PMID 34145050.

- ^ Campos, Guilherme M.; Khoraki, Jad; Browning, Matthew G.; Pessoa, Bernardo M.; Mazzini, Guilherme S.; Wolfe, Luke (February 2020). "Changes in Utilization of Bariatric Surgery in the United States From 1993 to 2016". Annals of Surgery. 271 (2): 201–209. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003554. ISSN 1528-1140. PMID 31425292. S2CID 201098614.

- ^ Campos, Guilherme M.; Khoraki, Jad; Browning, Matthew G.; Pessoa, Bernardo M.; Mazzini, Guilherme S.; Wolfe, Luke (February 2020). "Changes in Utilization of Bariatric Surgery in the United States From 1993 to 2016". Annals of Surgery. 271 (2): 201–209. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003554. ISSN 1528-1140. PMID 31425292. S2CID 201098614.

- ^ Inge, Thomas H.; Coley, R. Yates; Bazzano, Lydia A.; Xanthakos, Stavra A.; McTigue, Kathleen; Arterburn, David; Williams, Neely; Wellman, Rob; Coleman, Karen J.; Courcoulas, Anita; Desai, Nirav K. (2018). "Comparative effectiveness of bariatric procedures among adolescents: the PCORnet bariatric study". Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 14 (9): 1374–1386. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2018.04.002. PMC 6165694. PMID 29793877.

- ^ a b c Hofmann B (April 2013). "Bariatric surgery for obese children and adolescents: a review of the moral challenges". BMC Medical Ethics. 14 (1): 18. doi:10.1186/1472-6939-14-18. PMC 3655839. PMID 23631445.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Childhood Obesity Facts". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 17 March 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ^ Caniano DA (August 2009). "Ethical issues in pediatric bariatric surgery". Seminars in Pediatric Surgery. 18 (3): 186–92. doi:10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2009.04.009. PMID 19573761.

- ^ Ells LJ, Mead E, Atkinson G, Corpeleijn E, Roberts K, Viner R, Baur L, Metzendorf MI, Richter B (June 2015). "Surgery for the treatment of obesity in children and adolescents" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD011740. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011740. PMID 26104326. S2CID 37383758.

- ^ Zeller MH, Roehrig HR, Modi AC, Daniels SR, Inge TH (April 2006). "Health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms in adolescents with extreme obesity presenting for bariatric surgery". Pediatrics. 117 (4): 1155–61. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1141. PMID 16585310. S2CID 8099778.

- ^ "Alumni Interview: Edward Mason, M.D". Medicine Alumni Society, University of Iowa. Archived from the original on 2014-08-10. Retrieved 2014-08-09.

External links

Media related to Bariatric surgery at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bariatric surgery at Wikimedia Commons