Capoeira

Capoeira or the Dance of War by Johann Moritz Rugendas, 1825, published in 1835 | |

| Focus | Kicking, Striking |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Brazil |

| Famous practitioners | Mestre Bimba, Mestre Pastinha, Mestre Sinhozinho, Mestre João Grande, Mestre João Pereira dos Santos, Mestre Ananias, Mestre Sombra, Mestre Norival Moreira de Oliveira, Mestra Janja, fr:Mestre Cabeludo, Mestre Caramuru, Mestre Cobra Mansa, Jairo, Junior dos Santos, Wesley Snipes, Mark Dacascos, Anderson Silva, Lateef Crowder dos Santos, Cesar Carneiro, Jose Aldo |

Capoeira (Portuguese pronunciation: [kapuˈe(j)ɾɐ]) is a Brazilian martial art that combines elements of dance,[1][2][3] acrobatics,[4] music and spirituality.[5][6][7][8] Born of the melting pot of enslaved Africans, Indigenous Brazilians and Portuguese influences[9] at the beginning of the 16th century, capoeira is a constantly evolving art form.[10] It is known for its acrobatic and complex maneuvers, often involving hands on the ground and inverted kicks. It emphasizes flowing movements rather than fixed stances; the ginga, a rocking step, is usually the focal point of the technique. The most widely accepted origin of the word capoeira comes from the Tupi words ka'a ("forest") paũ ("round"),[11] referring to the areas of low vegetation in the Brazilian interior where fugitive slaves would hide. A practitioner of the art is called a capoeirista (Portuguese pronunciation: [kapue(j)ˈɾistɐ]).[12][13]

Though often said to be a martial art disguised as a dance,[14] capoeira served not only as a form of self defence, but also as a way to maintain spirituality and culture.[15] After the abolition of slavery in Brazil, capoeira was declared illegal in 1888. However, in the early 1930s, Mestre Bimba created a form of capoeira that held back on its spiritual elements and incorporated elements of jiu jitsu, gymnastics and sports.[16] In doing so, the government viewed capoeira as a socially acceptable sport. In the late 1970s, trailblazers such as Mestre Acordeon started bringing capoeira to the US and Europe, helping the art become internationally recognized and practiced. On 26 November 2014, capoeira was granted a special protected status as intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO.[17]

History

Origins

In the 16th century, Portugal had claimed one of the largest territories of the colonial empires, but lacked people to colonize it, especially workers. In the Brazilian colony, the Portuguese, like many European colonists, chose to use slavery to build their economy.

In its first century, the main economic activity in the colony was the production and processing of sugar cane. Portuguese colonists created large sugarcane farms called "engenhos", literally "engines" (of economic activity), which depended on the labor of slaves. Slaves, living in inhumane conditions, were forced to work hard and often suffered physical punishment for small infractions.[18]

Although slaves often outnumbered colonists, rebellions were rare because of the lack of weapons, harsh colonial law, disagreement between slaves coming from different African cultures, and lack of knowledge about the new land and its surroundings.

Capoeira originated as a product of the Angolan tradition of "Engolo" but became applied as a method of survival that was known to slaves. It was a tool with which an escaped slave, completely unequipped, could survive in the hostile, unknown land and face the hunt of the capitães-do-mato, the armed and mounted colonial agents who were charged with finding and capturing escapees.[19]

As Brazil became more urbanised in the 17th and 18th centuries, the nature of capoeira stayed largely the same. However, the nature of slavery differed from that in the United States. Since many slaves worked in the cities and were most of the time outside the master's supervision, they would be tasked with finding work to do (in the form of any manual labour) and in return, they would pay the master a share of the money they made. It is here where capoeira was common as it created opportunities for slaves to practice during and after work. Though tolerated until the 1800s, this quickly became criminalised due to its association with being African, as well as a threat to the current ruling regime.[20]

Quilombos

Soon several groups of enslaved persons who liberated themselves gathered and established settlements, known as quilombos, in remote and hard-to-reach places. Some quilombos would soon increase in size, attracting more fugitive slaves, Brazilian natives and even Europeans escaping the law or Christian extremism. Some quilombos would grow to an enormous size, becoming a real independent multi-ethnic state.[21]

Everyday life in a quilombo offered freedom and the opportunity to revive traditional cultures away from colonial oppression.[21] In this kind of multi-ethnic community, constantly threatened by Portuguese colonial troops, capoeira evolved from a survival tool to a martial art focused on war.

The biggest quilombo, the Quilombo dos Palmares, consisted of many villages which lasted more than a century, resisting at least 24 small attacks and 18 colonial invasions. Portuguese soldiers sometimes said that it took more than one dragoon to capture a quilombo warrior since they would defend themselves with a strangely moving fighting technique. The provincial governor declared "it is harder to defeat a quilombo than the Dutch invaders."[21]

Urbanization

In 1808, the prince and future king Dom João VI, along with the Portuguese court, escaped to Brazil from the invasion of Portugal by Napoleon's troops. Formerly exploited only for its natural resources and commodity crops, the colony finally began to develop as a nation.[22] The Portuguese monopoly effectively came to an end when Brazilian ports opened for trade with friendly foreign nations.[23] Those cities grew in importance and Brazilians got permission to manufacture common products once required to be imported from Portugal, such as glass.[22]

Registries of capoeira practices existed since the 18th century in Rio de Janeiro, Salvador and Recife. Due to city growth, more slaves were brought to cities and the increase in social life in the cities made capoeira more prominent and allowed it to be taught and practiced among more people. Because capoeira was often used against the colonial guard, the colonial government in Rio tried to suppress the martial art, and established severe physical punishments to its practice, including hunting down practitioners and killing them openly.[24]

Ample data from police records from the 1800s shows that many slaves and free colored people were detained for practicing capoeira:

"From 288 slaves that entered the Calabouço jail during the years 1857 and 1858, 80 (31%) were arrested for capoeira, and only 28 (10.7%) for running away. Out of 4,303 arrests in Rio police jail in 1862, 404 detainees—nearly 10%—had been arrested for capoeira."[25]

End of slavery and prohibition of capoeira

By the end of the 19th century, slavery was on the verge of departing the Brazilian Empire. Reasons included growing quilombo militia raids in plantations that still used slaves, the refusal of the Brazilian army to deal with escapees and the growth of Brazilian abolitionist movements. The Empire tried to soften the problems with laws to restrict slavery, but finally Brazil would recognize the end of the institution on 13 May 1888, with a law called Lei Áurea (Golden Law), sanctioned by imperial parliament and signed by Princess Isabel.

However, free former slaves now felt abandoned. Most of them had nowhere to live, no jobs and were despised by Brazilian society, which usually viewed them as lazy workers.[26][27] Also, new immigration from Europe and Asia left most former slaves with no employment.[27][28]

Soon capoeiristas started to use their skills in unconventional ways. Criminals and warlords used capoeiristas as bodyguards and assassins. Groups of capoeiristas, known as maltas, raided Rio de Janeiro. The two main maltas were the Nagoas, composed of Africans, and the Guaiamuns, composed of native blacks, people of mixed race, poor whites, and Portuguese immigrants. The Nagoas and Guaiamuns were used, respectively, as a hitforce by the Conservative and Liberal party.[29] In 1890, the recently proclaimed Brazilian Republic decreed the prohibition of capoeira in the whole country.[30] Social conditions were chaotic in the Brazilian capital, and police reports identified capoeira as an advantage in fighting.[28]

After the prohibition, any citizen caught practicing capoeira, in a fight or for any other reason, would be arrested, tortured and often mutilated by the police.[31] Cultural practices, such as the roda de capoeira, were conducted in remote places with sentries to warn of approaching police.

Systematization of the art

By the 1920s, capoeira repression had declined, and some physical educators and martial artists started to incorporate capoeira as either a fighting style or a gymnastic method. Professor Mario Aleixo was the first in showing a capoeira "revised, made bigger and better", which he mixed with judo, wrestling, jogo do pau and other arts to create what he called "Defesa Pessoal" ("Personal Defense").[1][32] In 1928, Anibal "Zuma" Burlamaqui published the first capoeira manual, Ginástica nacional, Capoeiragem metodizada e regrada, where he also introduced boxing-like rules for capoeira competition. It was greatly influential, being even taught at academies.[32] Inezil Penha Marinho published a similar book.[1] Felix Peligrini founded a capoeira school in the 1920s, intending to practice it scientifically,[32] while Mestre Sinhozinho from Rio de Janeiro went further in 1930, creating a training method that divested capoeira from all its music and traditions in the process of making it a complete martial art.[33]

While those efforts helped to keep capoeira alive,[33] they also had the consequence that the pure, non-adulterated form of capoeira became increasingly rare.[1]

At the same time, Mestre Bimba from Salvador, a traditional capoeirista with both legal and illegal fights in his records, met with his future student Cisnando Lima, a martial arts aficionado who had trained judo under Takeo Yano. Both thought traditional capoeira was losing its martial roots due to the use of its playful side to entertain tourists, so Bimba began developing the first systematic training method for capoeira, and in 1932 founded the first official capoeira school.[34] Advised by Cisnando, Bimba called his style Luta Regional Baiana ("regional fight from Bahia"), because capoeira was still illegal in name.[35] At the time, capoeira was also known as "capoeiragem", with a practitioner being known as a "capoeira", as reported in local newspapers. Gradually, the art dropped the term to be known as "capoeira" with a practitioner being called a "capoeirista".[36]

In 1937, Bimba founded the school Centro de Cultura Física e Luta Regional, with permission from Salvador's Secretary of Education (Secretaria da Educação, Saúde e Assistência de Salvador). His work was very well received, and he taught capoeira to the cultural elite of the city.[35] By 1940, capoeira finally lost its criminal connotation and was legalized.

Bimba's Regional style overshadowed traditional capoeiristas, who were still distrusted by society. This began to change in 1941 with the founding of Centro Esportivo de Capoeira Angola (CECA) by Mestre Pastinha. Located in the Salvador neighborhood of Pelourinho, this school attracted many traditional capoeiristas. With CECA's prominence, the traditional style came to be called Capoeira Angola. The name derived from brincar de angola ("playing Angola"), a term used in the 19th century in some places. But it was also adopted by other masters, including some who did not follow Pastinha's style.[37]

Though there was some degree of tolerance, capoeira from the beginning of the 20th century began to become a more sanitised form of dance with less martial application. This was due to the reasons mentioned above but also due to the military coup in the 1930s to 1945, as well as the military regime from 1964 to 1985. In both cases, capoeira was still seen by authorities as a dangerous pastime which was punishable; however, during the Military Regime it was tolerated as an activity for University students (which by this time is the form of capoeira that is recognised today).[citation needed]

Today

Capoeira is an active exporter of Brazilian culture all over the world. In the 1970s, capoeira mestres began to emigrate and teach it in other countries. Present in many countries on every continent, every year capoeira attracts thousands of foreign students and tourists to Brazil. Foreign capoeiristas work hard to learn Portuguese to better understand and become part of the art. Renowned capoeira mestres often teach abroad and establish their own schools. Capoeira presentations, normally theatrical, acrobatic and with little martiality, are common sights around the world.[17]

In 2014 the Capoeira Circle was added to UNESCO's Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, the convention recognised that the "capoeira circle is a place where knowledge and skills are learned by observation and imitation" and that it "promotes social integration and the memory of resistance to historical oppression".[17][38]

-

Practicing capoeira in Yoyogi Park, Japan

-

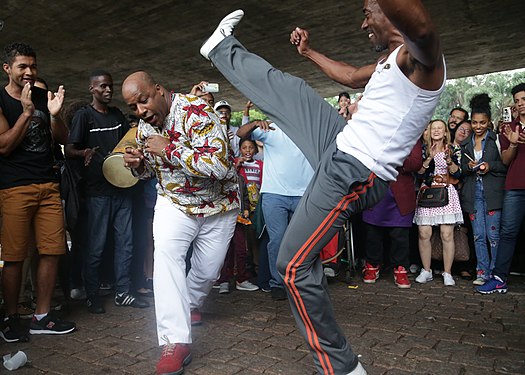

A capoeira demonstration at the

Helsinki Samba Carnaval in Finland

Techniques

Capoeira is a fast and versatile martial art that is historically focused on fighting when outnumbered or at a technological disadvantage. The style emphasizes using the lower body to kick, sweep and take down their aggressors, using the upper body to assist those movements and occasionally attack as well. It features a series of complex positions and body postures that are meant to get chained in an uninterrupted flow, to strike, dodge and move without breaking motion, conferring the style with a characteristic unpredictability and versatility.

The ginga (literally: rocking back and forth; to swing) is the fundamental movement in capoeira, important both for attack and defense purposes. It has two main objectives. One is to keep the capoeirista in a state of constant motion, preventing them from being a still and easy target. The other, using also fakes and feints, is to mislead, fool or trick the opponent, leaving them open for an attack or a counter-attack.

The attacks in the capoeira should be done when opportunity arises, and though they can be preceded by feints or pokes, they must be precise and decisive, like a direct kick to the head, face or a vital body part, or a strong takedown. Most capoeira attacks are made with the legs, like direct or swirling kicks, rasteiras (leg sweeps), tesouras or knee strikes. Elbow strikes, punches and other forms of takedowns complete the main list. The head strike is a very important counter-attack move.

The defense is based on the principle of non-resistance, meaning avoiding an attack using evasive moves instead of blocking it. Avoids are called esquivas, which depend on the direction of the attack and intention of the defender, and can be done standing or with a hand leaning on the floor. A block should only be made when the esquiva is completely non-viable. This fighting strategy allows quick and unpredictable counterattacks, the ability to focus on more than one adversary and to face empty-handed an armed adversary.

A series of rolls and acrobatics (like the cartwheels called aú or the transitional position called negativa) allows the capoeirista to quickly overcome a takedown or a loss of balance, and to position themselves around the aggressor to lay up for an attack. It is this combination of attacks, defense and mobility that gives capoeira its perceived "fluidity" and choreography-like style.

Weapons

Through most of its history in Brazil, capoeira commonly featured weapons and weapon training, given its street fighting nature. Capoeiristas usually carried knives and bladed weapons with them, and the berimbau could be used to conceal those inside, or even to turn itself into a weapon by attaching a blade to its tip.[32] The knife or razor was used in street rodas and/or against openly hostile opponents, and would be drawn quickly to stab or slash. Other hiding places for the weapons included hats and umbrellas.[32]

Mestre Bimba included in his teachings a curso de especialização or "specialization course", in which the pupils would be taught defenses against knives and guns, as well as the usage of knife, straight razor, scythe, club, chanfolo (double-edged dagger), facão (facón or machete) and tira-teima (cane sword).[1] Upon graduating, pupils were given a red scarf which marked their specialty. This course was scarcely used, and was ceased after some time. A more common custom practised by Bimba and his students, however, was furtively handing a weapon to a player before a jogo for them to use it to attack their opponent on Bimba's sign, with the other player's duty being to disarm them.[1]

This weapon training is almost completely absent in current capoeira teachings, but some groups still practice the use of razors for ceremonial usage in the rodas.

As a game

Playing capoeira is both a game and a method of practicing the application of capoeira movements in simulated combat. It can be played anywhere, but it's usually done in a roda. During the game most capoeira moves are used, but capoeiristas usually avoid using punches or elbow strikes unless it's a very aggressive game.[39]

The game usually does not focus on knocking down or destroying the opponent, rather it emphasizes skill. Capoeiristas often prefer to rely on a takedown like a rasteira, then allowing the opponent to recover and get back into the game. It is also very common to slow down a kick inches before hitting the target, so a capoeirista can enforce superiority without the need of injuring the opponent. If an opponent clearly cannot dodge an attack, there is no reason to complete it. However, between two high-skilled capoeiristas, the game can get much more aggressive and dangerous. Capoeiristas tend to avoid showing this kind of game in presentations or to the general public.[citation needed]

Roda

The roda (pronounced [ˈʁodɐ]) is a circle formed by capoeiristas and capoeira musical instruments, where every participant sings the typical songs and claps their hands following the music. Two capoeiristas enter the roda and play the game according to the style required by the musical rhythm. The game finishes when one of the musicians holding a berimbau determines it, when one of the capoeiristas decides to leave or call the end of the game, or when another capoeirista interrupts the game to start playing, either with one of the current players or with another capoeirista.[40]

In a roda every cultural aspect of capoeira is present, not only the martial side. Aerial acrobatics are common in a presentation roda, while not seen as often in a more serious one. Takedowns, on the other hand, are common in a serious roda but rarely seen in presentations.[citation needed]

Batizado

The batizado (lit. baptism) is a ceremonial roda where new students will get recognized as capoeiristas and earn their first graduation. Also more experienced students may go up in rank, depending on their skills and capoeira culture. In Mestre Bimba's Capoeira Regional, batizado was the first time a new student would play capoeira following the sound of the berimbau.[citation needed]

Students enter the roda against a high-ranked capoeirista (such as a teacher or master) and normally the game ends with the student being taken down. In some cases the more experienced capoeirista can judge the takedown unnecessary. Following the batizado the new graduation, generally in the form of a cord, is given.[citation needed]

Apelido

Traditionally, the batizado is the moment when the new practitioner gets or formalizes their apelido (nickname). This tradition was created back when capoeira practice was considered a crime. To avoid having problems with the law, capoeiristas would present themselves in the capoeira community only by their nicknames. So if capoeiristas are captured by the police, they would be unable to identify their fellow capoeiristas, even when tortured.[citation needed]

Chamada

Chamada means 'call' and can happen at any time during a roda where the rhythm angola is being played. It happens when one player, usually the more advanced one, calls their opponent to a dance-like ritual. The opponent then approaches the caller and meets them to walk side by side. After it both resume normal play.[41]

While it may seem like a break time or a dance, the chamada is actually both a trap and a test, as the caller is just watching to see if the opponent will let his guard down so she can perform a takedown or a strike. It is a critical situation, because both players are vulnerable due to the close proximity and potential for a surprise attack. It's also a tool for experienced practitioners and masters of the art to test a student's awareness and demonstrate when the student left herself open to attack.[42]

The use of the chamada can result in a highly developed sense of awareness and helps practitioners learn the subtleties of anticipating another person's hidden intentions. The chamada can be very simple, consisting solely of the basic elements, or the ritual can be quite elaborate including a competitive dialogue of trickery, or even theatric embellishments.[42]

Volta ao mundo

Volta ao mundo means around the world.

The volta ao mundo takes place after an exchange of movements has reached a conclusion, or after there has been a disruption in the harmony of the game. In either of these situations, one player will begin walking around the perimeter of the circle counter-clockwise, and the other player will join the volta ao mundo in the opposite part of the roda, before returning to the normal game.[43]

Malandragem and mandinga

Malandragem is a word that comes from malandro, which means a person who possesses cunning as well as malícia (malice). This, however, is misleading as the meaning of malícia in capoeira is the capacity to understand someone's intentions. Malícia means making use of this understanding to misdirect someone as to your next move.[44] In the spirit of capoeira, this is done good-naturedly, contrary to what the word may suggest.[44] Men who used street smarts to make a living were called malandros.

In capoeira, malandragem is the ability to quickly understand an opponent's aggressive intentions, and during a fight or a game, fool, trick and deceive him.[45]

Similarly capoeiristas use the concept of mandinga. Mandinga can be translated "magic" or "spell", but in capoeira a mandingueiro is a clever fighter, able to trick the opponent. Mandinga is a tricky and strategic quality of the game, and even a certain esthetic, where the game is expressive and at times theatrical, particularly in the Angola style. The roots of the term mandingueiro would be a person who had the magic ability to avoid harm due to protection from the Orixás.[46]

Alternately Mandinga is a way of saying Mandinka (as in the Mandinka Nation) who are known as "musical hunters". Which directly ties into the term "vadiação". Vadiação is the musical wanderer (with flute in hand), traveler, vagabond.[citation needed]

Music

Music is integral to capoeira. It sets the tempo and style of game that is to be played within the roda. Typically the music is formed by instruments and singing. Rhythms (toques), controlled by a typical instrument called berimbau, differ from very slow to very fast, depending on the style of the roda.[47]

Instruments

Capoeira instruments are disposed in a row called bateria. It is traditionally formed by three berimbaus, two pandeiros, three atabaques, one agogô and one ganzá, but this format may vary depending on the capoeira group's traditions or the roda style.[citation needed]

The berimbau is the leading instrument, determining the tempo and style of the music and game played. Two low-pitch berimbaus (called berra-boi and médio) form the base and a high-pitch berimbau (called viola) makes variations and improvisations. The other instruments must follow the berimbau's rhythm, free to vary and improvise a little, depending upon the capoeira group's musical style.[48]

As the capoeiristas change their playing style significantly following the toque of the berimbau, which sets the game's speed, style and aggressiveness, it is truly the music that drives a capoeira game.[49]

Songs

Many of the songs are sung in a call and response format while others are in the form of a narrative. Capoeiristas sing about a wide variety of subjects. Some songs are about history or stories of famous capoeiristas. Other songs attempt to inspire players to play better. Some songs are about what is going on within the roda. Sometimes the songs are about life or love lost. Others have lighthearted and playful lyrics.[citation needed]

There are four basic kinds of songs in capoeira, the Ladaínha, Chula, Corrido and Quadra. The Ladaínha is a narrative solo sung only at the beginning of a roda, often by a mestre (master) or most respected capoeirista present. The solo is followed by a louvação, a call and response pattern that usually thanks God and one's master, among other things. Each call is usually repeated word-for-word by the responders. The Chula is a song where the singer part is much bigger than the chorus response, usually eight singer verses for one chorus response, but the proportion may vary. The Corrido is a song where the singer part and the chorus response are equal, normally two verses by two responses. Finally, the Quadra is a song where the same verse is repeated four times, either three singer verses followed by one chorus response, or one verse and one response.[citation needed]

Capoeira songs can talk about virtually anything, being it about a historical fact, a famous capoeirista, trivial life facts, hidden messages for players, anything. Improvisation is very important also, while singing a song the main singer can change the music's lyrics, telling something that's happening in or outside the roda.[citation needed]

Styles

Determining styles in capoeira is difficult, since there was never a unity in the original capoeira, or a teaching method before the decade of 1920. However, a division between two styles and a sub-style is widely accepted.[44]

Capoeira Angola

Capoeira de Angola refers to every capoeira that maintains traditions from before the creation of the regional style.

Existing in many parts of Brazil since colonial times, most notably in the cities of Rio de Janeiro, Salvador and Recife, it's impossible to tell where and when Capoeira Angola began taking its present form. The name Angola starts as early as the beginning of slavery in Brazil, when Africans, taken to Luanda to be shipped to the Americas, were called in Brazil "black people from Angola", regardless of their nationality. In some places of Brazil people would refer to capoeira as "playing Angola" and, according to Mestre Noronha, the capoeira school Centro de Capoeira Angola Conceição da Praia, created in Bahia, already used the name Capoeira Angola illegally in the beginning of the 1920 decade.[37]

The name Angola was finally immortalized by Mestre Pastinha at 23 February 1941, when he opened the Centro Esportivo de capoeira Angola (CECA). Pastinha preferred the ludic aspects of the game rather than the martial side, and was much respected by recognized capoeira masters. Soon many other masters would adopt the name Angola, even those who would not follow Pastinha's style.[citation needed]

The ideal of Capoeira Angola is to maintain capoeira as close to its roots as possible.[44] Characterized by being strategic, with sneaking movements executed standing or near the floor depending on the situation to face, it values the traditions of malícia, malandragem and unpredictability of the original capoeira.[44]

Typical music bateria formation in a roda of Capoeira Angola is three berimbaus, two pandeiros, one atabaque, one agogô and one ganzuá.[50]

Capoeira Regional

Capoeira Regional began to take form in the 1920s, when Mestre Bimba met his future student, José Cisnando Lima. Both believed that capoeira was losing its martial side and concluded there was a need to re-strengthen and structure it. Bimba created his sequências de ensino (teaching combinations) and created capoeira's first teaching method. Advised by Cisnando, Bimba decided to call his style Luta Regional Baiana, as capoeira was still illegal at that time.[51][52]

The base of capoeira regional is the original capoeira without many of the aspects that were impractical in a real fight, with less subterfuge and more objectivity. Training focuses mainly on attack, dodging and counter-attack, giving high importance to precision and discipline. Bimba also added a few moves from other arts, notably the batuque, an old street fight game invented by his father.[53] Use of jumps or aerial acrobatics stay to a minimum, since one of its foundations is always keeping at least one hand or foot firmly attached to the ground.

Capoeira Regional also introduced the first ranking method in capoeira. Regional had three levels: calouro (freshman), formado (graduated) and formado especializado (specialist). After 1964, when a student completed a course, a special celebration ceremony occurred, ending with the teacher tying a silk scarf around the capoeirista's neck.[54]

The traditions of roda and capoeira game were kept, being used to put into use what was learned during training. The disposition of musical instruments, however, was changed, being made by a single berimbau and two pandeiros.[citation needed]

The Luta Regional Baiana soon became popular, finally changing capoeira's bad image. Mestre Bimba made many presentations of his new style, but the best known was the one made at 1953 to Brazilian president Getúlio Vargas, where the president would say: "A Capoeira é o único esporte verdadeiramente nacional" (Capoeira is the only truly national sport).[55]

Capoeira Contemporânea

In the 1970s a mixed style began to take form, with practitioners taking the aspects they considered more important from both Regional and Angola. Notably more acrobatic, this sub-style is seen by some as the natural evolution of capoeira, by others as adulteration or even misinterpretation of capoeira.[citation needed]

Nowadays the label Contemporânea applies to any capoeira group who don't follow Regional or Angola styles, even the ones who mix capoeira with other martial arts. Some notable groups whose style cannot be described as either Angola or Regional but rather "a style of their own", include Senzala de Santos, Cordão de Ouro and Abada. In the case of Cordão de Ouro, the style may be described as "Miudinho", a low and fast-paced game, while in Senzala de Santos the style may described simply as "Senzala de Santos", an elegant, playful combination of Angola and Regional. Capoeira Abada may be described as a more aggressive, less dance-influenced style of capoeira.[citation needed]

Ranks

Because of its origin, capoeira never had unity or a general agreement. Ranking or graduating system follows the same path, as there never existed a ranking system accepted by most of the masters. That means graduation style varies depending on the group's traditions. The most common modern system uses colored ropes, called corda or cordão, tied around the waist. Some masters use different systems, or even no system at all.[56] In a substantial number of groups (mainly of the Angola school) there is no visible ranking system. There can still be several ranks: student, treinel, professor, contra-mestre and mestre, but often no cordas (belts).[57]

There are many entities (leagues, federations and association) with their own graduation system. The most usual is the system of the Confederação Brasileira de Capoeira (Brazilian Capoeira Confederation), which adopts ropes using the colors of the Brazilian flag, green, yellow, blue and white.[58] However, the Confederação Brasileira de Capoeira is not widely accepted as the capoeira's main representative.[citation needed]

Brazilian Capoeira Confederation system

Source:[58]

Children's system (3 to 14 years)

- 1st stage: Iniciante (Beginner) - No color

- 2nd stage: Batizado (Baptized) - Green/Light Grey

- 3rd stage: Graduado (Graduated) - Yellow/Light Grey

- 4th stage: Adaptado (Adept) - Blue/Light Grey

- 5th stage: Intermediário (Intermediary) - Green/YellowLight Grey

- 6th stage: Avançado (Advanced) - Green/Blue/Light Grey

- 7th stage: Estagiário (Trainee) - Yellow/Green/Blue/Light Grey

Adult system (above 15)

- 8th stage: Iniciante (Beginner) - No color

- 9th stage: Batizado (Baptized) - Green

- 10th stage: Graduado (Graduated) - Yellow

- 11th stage: Adaptado (Adept) - Blue

- 12th stage: Intermediário (Intermediary) - Green

- 13th stage: Avançado (Advanced) - Green/Blue

- 14th stage: Estagiário (Trainee) - Yellow/Blue

Instructors' system

- 15th stage: Formado (Graduated) - Yellow/Green/Blue

- 16th stage: Monitor (Monitor) - White/Green

- 17th stage: Instrutor (Instructor) - White/Yellow

- 18th stage: Contramestre (Foreman) - White/Blue

- 19th stage: Mestre (Master) - White

Related activities

Even though those activities are strongly associated with capoeira, they have different meanings and origins.

Samba de roda

Performed by many capoeira groups, samba de roda is a traditional Brazilian dance and musical form that has been associated with capoeira for many decades. The orchestra is composed by pandeiro, atabaque, berimbau-viola (high pitch berimbau), chocalho, accompanied by singing and clapping. Samba de roda is considered one of the primitive forms of modern Samba.

Maculelê

Originally the Maculelê is believed to have been an indigenous armed fighting style, using two sticks or a machete. Nowadays it's a folkloric dance practiced with heavy Brazilian percussion. Many capoeira groups include Maculelê in their presentations.

Puxada de rede

Puxada de Rede is a Brazilian folkloric theatrical play, seen in many capoeira performances. It is based on a traditional Brazilian legend involving the loss of a fisherman in a seafaring accident.

Sports development

Capoeira is currently being used as a tool in sports development (the use of sport to create positive social change) to promote psychosocial wellbeing in various youth projects around the world. Capoeira4Refugees is a UK-based NGO working with youth in conflict zones in the Middle East. Capoeira for Peace is a project based in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The Nukanti Foundation works with street children in Colombia. Capoeira Maculelê has social projects promoting cultural arts for wellness in Colombia, Angola, Brazil, Argentina, USA among others.

MMA

Many Brazilian mixed martial arts fighters have a capoeira background, either training often or having tried it before. Some of them include Anderson Silva, who is a yellow belt, trained in capoeira at a young age, then again when he was a UFC fighter; Thiago Santos, an active UFC middleweight contender who trained in capoeira for 8 years; Former UFC Heavyweight Champion Júnior dos Santos, who trained in capoeira as a child and incorporates its kicking techniques and movement into his stand up; Marcus "Lelo" Aurélio, who is famous for knocking a fighter out with a Meia-lua de Compasso kick, and UFC veterans José Aldo and Andre Gusmão also use capoeira as their base.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f Capoeira, Nestor (2012). Capoeira: Roots of the Dance-Fight-Game. North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-58394-637-4.

- ^ Ancona, George (2007). Capoeira: Game! Dance! Martial Art!. Lee & Low Books. ISBN 978-1-58430-268-1.

- ^ Goggerly, Liz (2011). Capoeira: Fusing Dance and Martial Arts. Lerner Publications. ISBN 978-0-7613-7766-5.

- ^ Poncianinho, Mestre; Almeida, Ponciano (2007). Capoeira: The Essential Guide to Mastering the Art. New Holland. ISBN 978-1-84537-761-8.

- ^ Hofling, A. P. (2008). "Merrell, Floyd. Capoeira and Candomble: Conformity and Resistance Through Afro-Brazilian Experience. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2005. 317 pp". Luso-Brazilian Review. 45: 222–223. doi:10.1353/lbr.0.0013. S2CID 219193367.

- ^ Dils, Ann; Cooper Albright, Ann (2001). Moving History/Dancing Cultures: A Dance History Reader. Wesleyan University Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-8195-6413-9.

- ^ Cachorro, Ricardo (2012). Unknown Capoeira: A History of the Brazilian Martial Art. Vol. 2. Blue Snake Books. ISBN 978-1-58394-234-5.

- ^ "Capoeira DANCE-LIKE MARTIAL ART". www.britannica.com.

- ^ "Estado é exaltado em festa nacional" (in Brazilian Portuguese). Ministério da Cultura. Archived from the original on 17 November 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ Assunção 2005, pp. 5–27.

- ^ "Definition of CAPOEIRA". merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ "Hoje é Dia do Capoeirista" (in Brazilian Portuguese). Ministério da Cultura do Govermo do Brasil. Archived from the original on 17 November 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ "Como surgiu a capoeira?" (in Brazilian Portuguese). Revista Mundo Estranho. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ All you need to know about: Capoeira www.theguardian.com

- ^ Willson, Margaret (2001). "Designs of Deception: Concepts of Consciousness, Spirituality and Survival in Capoeira Angola in Salvador, Brazil". Anthropology of Consciousness. 12: 19–36. doi:10.1525/ac.2001.12.1.19. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ "Histoire de la capoeira".

- ^ a b c "Brazil's capoeira gets Unesco status". BBC News. 26 November 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ "O Brasil no quadro do Antigo Sistema Colonial" (in Portuguese). Culturabrasil.pro.br. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ^ "Capoeira History". Capoeira Centre Manchester.

- ^ Desch-Obi, T. J. "Capoeira." Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History, edited by Colin A. Palmer, 2nd ed., vol. 2, Macmillan Reference USA, 2006, pp. 395-398. Gale eBooks, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX3444700236/GVRL?u=tamp44898&sid=GVRL&xid=fe4652ba. Accessed 19 Jan. 2021.

- ^ a b c Gomes, Flávio (2010). Mocambos de Palmares; histórias e fontes (séculos XVI–XIX) (in Portuguese). Editora 7 Letras. ISBN 978-85-7577-641-4.

- ^ a b Gomes, Laurentino (2007). 1808; Como uma rainha louca, um príncipe medroso e uma corte corrupta enganaram Napoleão e mudaram a História de Portugal e do Brasil (in Portuguese). Editora Planeta. ISBN 978-85-7665-320-2.

- ^ Vimmar Comunicação Digital. "Abertura Dos Portos Às Nações Amigas – 1808". Historiadobrasil.net. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ^ "Gangues do Rio: Capoeira era reprimida no Brasil" (in Portuguese). Guiadoestudante.abril.com.br. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ^ Assunção 2005

- ^ Empty webpage at www.brasil.gov.br/sobre/historia/abolicao (archived copy) [dead link]

- ^ a b Cardoso, Fernando Henrique (1962). Capitalismo e Escravidão no Brasil Meridional (in Portuguese). Editora Civilização Brasileira. ISBN 978-85-200-0635-1.

- ^ a b Campos, Andrelino (2005). Do Quilombo à Favela: A Produção do "Espaço Criminalizado" no Rio de Janeiro (in Portuguese). Editora Bertrand Brasil. ISBN 978-85-286-1159-5.

- ^ a-capoeira-na-politica-as-maltaswww.vermelho.org.br Archived 12 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Código penal brasileiro – proibição da capoeira – 1890 – Wikisource" (in Portuguese). Pt.wikisource.org. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ^ Assuncao, Matthias Rohrig; Assunção, Matthias Röhrig (2005). Capoeira: The History of an Afro-Brazilian Martial Art. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7146-5031-9.

- ^ a b c d e Gerard Taylor, Capoeira: The Jogo de Angola from Luanda to Cyberspace, vol. 2 (Berkeley CA: Blue Snake Books, 2007), ISBN 1583941835, 9781583941836

- ^ a b André Luiz Lacé Lopes (2015). A capoeiragem no Rio de Janeiro, primeiro ensaio: Sinhozinho e Rudolf Hermanny. Editorial Europa. ISBN 978-85-900795-2-1.

- ^ Kingsford-Smith, Andrew. "Disguised In Dance: The Secret History Of Capoeira". Culture Trip. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ a b Sodre, Muniz (2002). Mestre Bimba: Corpo de Mandiga (in Portuguese). Livraria da Travessa. ISBN 978-85-86218-13-2.

- ^ Roberto Pedreira, Choque: The Untold Story of Jiu-Jitsu in Brazil 1856–1949

- ^ a b "O ABC da Capoeira Angola – Os Manuscritos de Mestre Noronha | Publicaçþes e Artigos – Capoeira". Portalcapoeira.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ^ "UNESCO – Capoeira circle". Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. 2014.

- ^ Crocitti, John J. Vallance, Monique M. (2012). Brazil today : an encyclopedia of life in the republic. Calif. ISBN 978-0-313-34672-9. OCLC 810633190.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ DOWNING, BEN (1996). "Jôgo Bonito: A Brief Anatomy of Capoeira". Southwest Review. 81 (4): 545–562. ISSN 0038-4712. JSTOR 43471791.

- ^ "Capoeira – The Martial Arts Encyclopedia". bullshido.org. Archived from the original on 10 April 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ a b "Capoeira: An Ancient Brazilian Fitness Routine". Women Fitness. 10 November 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ Neto, Vianna. "Capoeira and Transnational Culture" (PDF). Griffith University. Vianna Neto & Eurico Lopez Baretto. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Contemporary Latin American cultural studies. Stephen M. Hart, Richard Young. London: Arnold. 2003. pp. 285–286. ISBN 0-340-80821-7. OCLC 52946422.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Diaz, J. D. (2017). Between repetition and variation: A musical performance of malícia in capoeira. Ethnomusicology Forum, 26(1), 46–68. doi:10.1080/17411912.2017.1309297

- ^ "O Fio Da Navalha", ESPN Brasil documentary, 2007

- ^ "The History of Capoeira". Capoeira Brasil. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ Assunção, M. R. (2002). Workers, vagrants, and tough guys in Bahia, c. 1860-1950. In Capoeira: The history of an Afro-Brazilian martial art (pp. 93-124). Taylor & Francis Group.

- ^ "Instruments of Capoeira: The Music That Drives Movement". LV Capoeira. 21 April 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "What musical instruments are used in capoeira? | Capoeira Connection". capoeira-connection.com. 26 October 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ^ Matthias Röhrig Assunção, Capoeira: A History of an Brazilian Martial Art (London: Psychology/Routledge, 2005), 133–35. ISBN 0714650315, 9780714650319; Aniefre Essien, Capoeira Beyond Brazil: From a Slave Tradition to an International Way of Life (Berkeley CA: Blue Snake Books, 2008), 6–8. ISBN 1583942556, 9781583942550

- ^ Taylor, Pp. 233–35.

- ^ “I challenged all the tough guys” – Mestre Bimba, 1973 Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine capoeira-connection.com

- ^ Taylor, Page 234.

- ^ Campos, Hellio (2009), "Capoeira Regional", Capoeira Regional: A escola de Mestre Bimba, EDUFBA, pp. 62–69, doi:10.7476/9788523217273.0007, ISBN 9788523217273

- ^ "Capoeira Ranking- Capoeira Cord System". Capoeira-World.com. 2015. Archived from the original on 28 May 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ "Angola High School". U.S. News. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ a b "CBC - CONFEDERAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE CAPOEIRA". www.cbcapoeira.com.br. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

Bibliography

- Assunção, Matthias Röhrig (2005). Capoeira: The History of an Afro-Brazilian Martial Art. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-8086-6.

- Capoeira, Nestor (2003). The Little Capoeira Book. Translated by Ladd, Alex. North Atlantic. ISBN 978-1-55643-440-2.

- Talmon-Chvaicer, Maya (2007). The Hidden History of Capoeira: A Collision of Cultures in the Brazilian Battle Dance. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71723-7.

Further reading

- Almeida, Bira "Mestre Acordeon" (1986). Capoeira: A Brazilian Art Form. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-0-938190-30-1.

- Downey, Greg (2005). Learning Capoeira: Lessons in cunning from an Brazilian art. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195176988.

- Mason, Paul H. (2013). "Intracultural and Intercultural Dynamics of Capoeira" (PDF). Global Ethnographic. 1: 1–8.

- Merrell, Floyd (2005). Capoeira and Candomblé: Conformity and Resistance in Brazil. Princeton: Markus Wiener. ISBN 978-1-55876-349-4.

- Stephens, Neil; Delamont, Sara (2006). "Balancing the Berimbau Embodied Ethnographic Understanding". Qualitative Inquiry. 12 (2): 316–339. doi:10.1177/1077800405284370. S2CID 143105472.