Inquisition

The Inquisition, Inquisitio Haereticae Pravitatis (inquiry on heretical perversity), was the "fight against heretics" by several institutions within the justice system of the Roman Catholic Church. It started in the 12th century, with the introduction of torture in the persecution of heresy.[1] Inquisition practices were used also on offences against canon law other than heresy.

Definition

The term "Inquisition" can apply to any one of several institutions which fought against heretics (or other offenders against canon law) within the justice-system of the Roman Catholic Church. The term "Inquisition" is usually applied to that of the Catholic Church. It may also refer to:[2]

- an ecclesiastical tribunal

- the institution of the Catholic Church for combating heresy

- a number of historical expurgation movements against heresy (orchestrated by some groups/individuals within the Catholic Church or within a Catholic state)

- the trial of an individual accused of heresy.

Generally, the Inquisition movement was concerned only with the heretical behaviour of Catholic adherents or converts, and did not concern itself with those outside its jurisdiction, such as Jews or Muslims.[3]

Tribunals and institutions

Before 1100, the Catholic Church had already suppressed heresy, usually through a system of ecclesiastical proscription or imprisonment, but without using torture[1] and seldom resorting to executions.[4][5] Such punishments had a number of ecclesiastical opponents, although some countries punished heresy with the death penalty.[6][7]

In the 12th century, to counter the spread of Catharism, prosecution of heretics by secular governments became more frequent. The Church charged councils composed of bishops and archbishops with establishing inquisitions (see Episcopal Inquisition). The first Inquisition was established in Languedoc (south of France) in 1184.

In the 13th century, Pope Gregory IX (reigned 1227–1241) assigned the duty of carrying out inquisitions to the Dominican Order. They used inquisitorial procedures, a legal practice common at that time. They judged heresy alone, using the local authorities to establish a tribunal and to prosecute heretics. After 1200, a Grand Inquisitor headed each Inquisition. Grand Inquisitions persisted until the mid 19th century.[8]

By 1500, the Catholic Church had reached an apparently dominant position as the established religious authority in western and central Europe dominating a faith-landscape in which Judaism, Waldensianism, Hussitism, Lollardry and the finally conquered Muslims al-Andalus (the Muslim-dominated Spain) hardly figured in terms of numbers or influence. When the institutions of the Church felt themselves threatened by what they perceived as the heresy, and then schism of the Protestant Reformation, they reacted. Paul III (Pope from 1534 to 1549) established a system of tribunals, administered by the "Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Universal Inquisition", and staffed by cardinals and other Church officials. This system would later become known as the Roman Inquisition. In 1908 Pope Saint Pius X renamed the organisation: it became the "Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office". This in its turn became the "Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith"[9] in 1965, which name continues to this day[update].

Functional role

In practice, the Inquisition would not itself pronounce sentence, but handed over convicted heretics to secular authorities.[10] The laws were inclusive of proscriptions against certain religious crimes (heresy, etc.), and the punishments included death by burning. Thus the inquisitors generally knew what would be the fate of anyone so remanded, and cannot be considered to have divorced the means of determining guilt from its effects.[11]

Purpose

The 1578 handbook for inquisitors spelled out the purpose of inquisitorial penalties: ... quoniam punitio non refertur primo & per se in correctionem & bonum eius qui punitur, sed in bonum publicum ut alij terreantur, & a malis committendis avocentur. Translation from the Latin: ... for punishment does not take place primarily and per se for the correction and good of the person punished, but for the public good in order that others may become terrified and weaned away from the evils they would commit."[12]

Movements

Most of Medieval Western and Central Europe had a long-standing veneer of Catholic standardisation over traditional non-Christian practices, with intermittent localized occurrences of different ideas (such as Catharism or Platonism) and constantly recurring anti-Semitic or anti-Judaic activity and conspiration.

Exceptionally, Portugal and Spain in the late Middle Ages consisted largely of multicultural territories of muslim and jewish influence, conquered from the Islamic states of Al-Andalus control, and the new Christian authorities could not assume that all their subjects would suddenly become and remain orthodox Catholics. So the Inquisition in Iberia, in the lands of the Reconquista counties and kingdoms like Leon, Castile and Aragon, had a special socio-political basis as well as more fundamentalistic religious motives. Later followed Portugal in this fundamentalistic christianisation.

With the Protestant Reformation, Catholic authorities became much more ready to suspect heresy in any new ideas,[13] including those of Renaissance humanism,[14] previously strongly supported by many at the top of the Church hierarchy. The extirpation of heretics became a much broader and more complex enterprise, complicated by the politics of territorial Protestant powers, especially in northern Europe. The Catholic Church could no longer exercise direct influence in the politics and justice-systems of lands which officially adopted Protestantism. Thus war (the French Wars of Religion, the Thirty Years War), massacre (the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre) and the missional[15] and propaganda work (by the Sacra congregatio de propaganda fide)[16] of the Counter-Reformation came to play larger roles in these circumstances, and the roman law type of a "judicial" approach to heresy represented by the Inquisition became less important overall. Inquisition tribunals mostly functioned in Catholic territories, but christian law outside the church in both Catholic and Protestant countries could address the 'criminal offences' of heresy and witchcraft. [citation needed]

Historians distinguish four different manifestations of the Christian Inquisition:

- the Medieval Inquisition (1184–16th century), including

- the Episcopal Inquisition (1184–1230s)

- the Papal Inquisition (1230s) and following christian inquisitions

- the Spanish Inquisition (1478–1834)

- the Portuguese Inquisition (1536–1821)

- the Roman Inquisition (1542 – c. 1860)

Medieval Inquisition

Historians use the term "Medieval Inquisition" to describe the various inquisitions that started around 1184, including the Episcopal Inquisition (1184–1230s) and later the Papal Inquisition (1230s). These inquisitions responded to large popular movements throughout Europe considered apostate or heretical to Christianity, in particular the Cathars in southern France and the Waldensians in both southern France and northern Italy. Other Inquisitions followed after these first inquisition movements. Legal basis for some inquisitorial activity came from Pope Innocent IV's papal bull Ad extirpanda of 1252, which authorized and regulated the use of torture in investigating heresy. [citation needed]

Spanish Inquisition

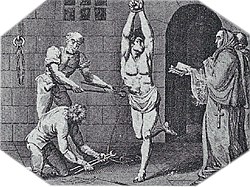

Many artistic representations depict torture and burning at the stake as occurring during the auto-da-fé.

King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile established the Spanish Inquisition in 1478. In contrast to the previous inquisitions, it operated completely under royal christian authority, though staffed by secular clergy and orders, and independently of the Holy See. It operated in Spain and in all Spanish colonies and territories, which included the Canary Islands, the Spanish Netherlands, the Kingdom of Naples, and all Spanish possessions in North, Central, and South America. It targeted primarily forced converts from Islam (Moriscos, Conversos and secret Moors) and converts from Judaism (Conversos, Crypto-Jews and Marranos) — both groups still resided in Spain after the end of the Islamic control of Spain — who came under suspicion of either continuing to adhere to their old religion or of having fallen back into it. Somewhat later the Spanish Inquisition took an interest in Protestants of virtually any sect, notably in the Spanish Netherlands, Heresy and Witchcraft. In the Spanish possessions of the Kingdom of Sicily and the Kingdom of Naples in southern Italy, which formed part of the Spanish Crown's hereditary possessions, it also targeted Greek Orthodox Christians. The Spanish Inquisition, tied to the authority of the Spanish Crown, also examined political cases. [citation needed]

In the Americas, King Philip II set up two tribunals (each formally titled Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición) in 1569, one in Mexico and the other in Peru. The Mexican office administered Mexico (central and southeastern Mexico), Nueva Galicia (northern and western Mexico), the Audiencias of Guatemala (Guatemala, Chiapas, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica), and the Spanish East Indies. The Peruvian Inquisition, based in Lima, administered all the Spanish territories in South America and Panama. From 1610 a new Inquisition seat established in Cartagena (Colombia) administered much of the Spanish Caribbean in addition to Panama and northern South America. [citation needed]

The Inquisition continued to function in North America until the Mexican War of Independence (1810–1821). In South America Simón Bolívar and Jose de San Martin abolished the Inquisition; in Spain itself the institution survived until 1834. [citation needed]

Portuguese Inquisition

The Portuguese Inquisition formally started in Portugal in 1536 at the request of the King of Portugal, João III. Manuel I had asked Pope Leo X for the installation of the Inquisition in 1515, but only after his death (1521) did Pope Paul III acquiesce. The Portuguese Inquisition principally targeted the Sephardic Jews, whom the state forced to convert to Christianity. Spain had expelled its Sephardic population in 1492 (see Alhambra decree); after 1492 many of these Spanish Jews left Spain for Portugal, but eventually were targeted there as well. The Portuguese Inquisition came under the authority of the King. At its head stood a Grande Inquisidor, or General Inquisitor, named by the Pope but selected by the Crown, and always from within the royal family. The Grande Inquisidor would later nominate other inquisitors. In Portugal, Cardinal Henry served as the first Grand Inquisitor: he would later become King Henry of Portugal. Courts of the Inquisition operated in Lisbon, Porto, Coimbra, and Évora. [citation needed]

The Portuguese Inquisition held its first auto-da-fé in 1540. It concentrated its efforts on rooting out converts from other faiths (overwhelmingly Judaism) who did not adhere to the observances of Catholic orthodoxy; the Portuguese inquisitors mostly targeted the Jewish "New Christians" (i.e. conversos or marranos). The Portuguese Inquisition expanded its scope of operations from Portugal to Portugal's colonial possessions, including Brazil, Cape Verde, and Goa, where it continued as a religious court, investigating and trying cases of breaches of the tenets of orthodox Roman Catholicism until 1821. King João III (reigned 1521–57) extended the activity of the courts to cover censorship, divination, witchcraft and bigamy. Originally oriented for a religious action, the Inquisition had an influence in almost every aspect of Portuguese society: politically, culturally and socially. The Goa Inquisition, an inquisition largely aimed at Catholic converts from Hinduism or Islam who were thought to have returned to their original ways, started in Goa in 1560. In addition, the Inquisition prosecuted non-converts who broke prohibitions against the observance of Hindu or Muslim rites or interfered with Portuguese attempts to convert non-Christians to Catholicism.[3] Aleixo Dias Falcão and Francisco Marques set it up in the palace of the Sabaio Adil Khan.

According to Henry Charles Lea[18] between 1540 and 1794 tribunals in Lisbon, Porto, Coimbra and Évora resulted in the burning of 1,175 persons, the burning of another 633 in effigy, and the penancing of 29,590. But documentation of fifteen out of 689[19] Template:Que In the wake of the Liberal Revolution of 1820, the "General Extraordinary and Constituent Courts of the Portuguese Nation" abolished the Portuguese inquisition in 1821.

Roman Inquisition

In 1542 Pope Paul III established the Congregation of the Holy Office of the Inquisition as a permanent congregation staffed with cardinals and other officials. It had the tasks of maintaining and defending the integrity of the faith and of examining and proscribing errors and false doctrines;[20] it thus became the supervisory body of local Inquisitions. Arguably the most famous case tried by the Roman Inquisition involved Galileo Galilei in 1633.

The penances and sentences for those who confessed or were found guilty were pronounced together in a public ceremony at the end of all the processes. This was the sermo generalis or auto-da-fé.[21] Penances might consist of a pilgrimage, a public scourging, a fine, or the wearing of a cross. The wearing of two tongues of red or other brightly colored cloth, sewn onto an outer garment in an "X" pattern, marked those who were under investigation. The penalties in serious cases were confiscation of property or imprisonment. The most severe penalty the inquisitors could themselves impose was life imprisonment. [citation needed]

Following the French invasion of 1798, the new authorities sent 3,000 chests containing over 100,000 Inquisition documents to France from Rome. After the restoration of the Pope as the ruler of the Papal States after 1814, Roman Inquisition activity continued until the mid-19th century, notably in the well-publicised Mortara Affair (1858–1870). In 1908 the name of the Congregation became "The Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office", which in 1965 further changed to "Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith", as retained to the present day[update]. The Pope appoints a cardinal to preside over the Congregation, which usually includes ten other cardinals, as well as a prelate and two assistants, all chosen from the Dominican Order. The "Holy Office" also has an international group of consultants, experienced scholars in theology and canon law, who advise it on specific questions. [citation needed]

Reputation(s)

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2010) |

With the sharpening of debate and of conflict between the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation, Protestant societies came to see/use the Inquisition as a terrifying "Other" trope,[22] while staunch Catholics regarded the Holy Office as a necessary bulwark against the spread of reprehensible heresies. [citation needed] Some of the fictional works mentioned below reflect the popular reputation of the Inquisition as much as its historicity.

Derivative works

The Inquisitions appear in many cultural works. Some include:

- The Grand Inquisitor, a parable told by Ivan to Alyosha in Fyodor Dostoevsky's novel The Brothers Karamazov (1879–1880).

- The Spanish Inquisition, the subject of a classic Monty Python sketch of 1970 ("Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!"), became referenced conspicuously in the film Sliding Doors (1998).

- The short story by Edgar Allan Poe, "The Pit and the Pendulum" takes place against the background of the Spanish Inquisition.

- "The Torture of Hope", a short story by Jean-Marie Villiers de l'Isle Adam.

- In the alternative history novel The Two Georges by Harry Turtledove and Richard Dreyfuss, the Spanish Inquisition remains active, in Spain itself and throughout Latin America, during the whole of the 20th century.

- A body known as the Inquisition exists in the fictional Warhammer 40,000 universe, with a similar purpose.

- Mel Brooks's 1981 film The History of the World, Part I contains a musical number about the Spanish Inquisition.

- In Terry Pratchett's Small Gods, the Omnian church has a Quisition, with sub-sections called Inquisition and Exquisition: "... some of the inquisitors had an enviable knowledge of the insides of the human body that is denied to all those who are not allowed to open it while it's still working ..."

- In J.K. Rowling's 2003 book Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, Professor Dolores Umbridge sets up an Inquisition at the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, with herself as the High Inquisitor.

- The "Dark Ages" setting in the World of Darkness (WoD) fantasy universe makes heavy use of the Inquisition: that particular setting takes place during the early 13th century.

- The computer game "Lionheart: Legacy of the Crusader" made by the former Black Isle Studios uses the Spanish Inquisition as a key plot element for the storyline and development of the game.

- Man of La Mancha, a Broadway musical, tells the story of the classic novel Don Quixote as a play-within-a-play performed by prisoners as they await a hearing with the Spanish Inquisition.

- Starways Congress forms an element of the Ender-verse by Orson Scott Card. In the later books, the inquisitors play an important part in determining the fate of the fictional planet Lusitania. In Speaker for the Dead, Ender Wiggin threatens to become an Inquisitor and thus revoke the catholic licence [clarification needed] of Lusitania, thus ruining the fragile catholic culture there.

- Voltaire's satire Candide has a scene featuring the Portuguese Inquisition, with the title character and Dr. Pangloss both found guilty of heresy.

- Arturo Ripstein's 1973 film The Holy Office (El santo oficio) about the Inquisition in New Spain (Mexico).

- Dave Sim's independent comic book Cerebus the Aardvark featured Inquisition-inspired characters in the "High Society" issues of the series.

- The 2006 film Goya's Ghosts starring Stellan Skarsgård, Natalie Portman, and Javier Bardem features the Spanish Inquisition. In the film, the painter Goya (Skarsgård) attempts to save his muse, Ines (Portman), from persecution by the Holy Office. He turns for help to Brother Lorenzo (Bardem), who, unknown to Goya, has an agenda of his own.

- The music video for the song It's A Sin by the Pet Shop Boys shows Neil Tennant under the influence of the Inquisition

- An example of a science-fiction type inquisition appears in "The Inquisitor", an episode of the British sci-fi series Red Dwarf, in which the villain holds inquisitions for the people he encounters.

- Inquisition, an underground newspaper published in Charlotte, North Carolina (1968–1969).

- Green, Toby (2008) [2007]. Inquisition: the reign of fear. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4050-8873-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origmonth=and|origdate=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Nemesis the Warlock by Pat Mills, originally published in 2000AD (comic), features the Spanish Inquisition and Tomas de Torquemada, who is the namesake of the antagonist in one of its books .

See also

- Historical revision of the Inquisition

- Inquisitorial system

- Marian Persecutions: Roman Catholic heretic-hunting in Tudor England

- Vatican Secret Archives

- Witchhunt

Documents and works

Notable inquisitors

Notable cases

- Trial of Joan of Arc

- Trial of Galileo Galilei

- Edgardo Mortara's abduction

- Logroño trials against Basque witches.

- Execution of Giordano Bruno

References

- ^ a b

Lea, Henry Charles (1888). "Chapter VII. The Inquisition Founded". A History of the Inquisition In The Middle Ages. Vol. 1. ISBN [[Special:BookSources/1-152-29621-3

span.brokenref {

display: inline;

}[dead link]|1-152-29621-3

span.brokenref {

display: inline;

}

[[Category:All articles with dead external links]][[Category:Articles with dead external links from February 2012]]<sup class="noprint Inline-Template"><span style="white-space: nowrap;">[<i>[[Wikipedia:Link rot|<span title=" Dead link tagged February 2012">dead link</span>]]</i>]</span></sup>]].

The judicial use of torture was as yet happily unknown [...]

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); line feed character in|isbn=at position 14 (help) - ^ Medieval Sourcebook: Inquisition - Introduction

- ^ a b Salomon, H. P. and Sassoon, I. S. D., in Saraiva, Antonio Jose. The Marrano Factory. The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians, 1536-1765 (Brill, 2001), Introduction pp. XXX. Cite error: The named reference "Salomon, H. P 2001 pp. 345-7" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Foxe's Book of Martyrs Chapter V

- ^

Blötzer, J. (1910). "Inquisition". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 2009-11-26.

... in this period the more influential ecclesiastical authorities declared that the death penalty was contrary to the spirit of the Gospel, and themselves opposed its execution. For centuries this was the ecclesiastical attitude both in theory and in practice. Thus, in keeping with the civil law, some Manichæans were executed at Ravenna in 556. On the other hand. Elipandus of Toledo and Felix of Urgel, the chiefs of Adoptionism and Predestinationism, were condemned by councils, but were otherwise left unmolested. We may note, however, that the monk Gothescalch, after the condemnation of his false doctrine that Christ had not died for all mankind, was by the Synods of Mainz in 848 and Quiercy in 849 sentenced to flogging and imprisonment, punishments then common in monasteries for various infractions of the rule

- ^

Blötzer, J. (1910). "Inquisition". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 2009-11-26.

[...] the occasional executions of heretics during this period must be ascribed partly to the arbitrary action of individual rulers, partly to the fanatic outbreaks of the overzealous populace, and in no wise to ecclesiastical law or the ecclesiastical authorities.

- ^

Lea, Henry Charles. "Chapter VII. The Inquisition Founded". A History of the Inquisition In The Middle Ages. Vol. 1. ISBN [[Special:BookSources/1-152-29621-3

span.brokenref {

display: inline;

msg=Dead Link

}|1-152-29621-3

span.brokenref {

display: inline;

msg=Dead Link

}]].

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origmonth=,|origdate=, and|month=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); line feed character in|isbn=at position 14 (help) - ^ [1]

- ^ Profile

- ^ Lea, Henry Charles. "Chapter VII. The Inquisition Founded". A History of the Inquisition In The Middle Ages. Vol. 1. ISBN 1-152-29621-3.

Obstinate heretics, refusing to abjure and return to the Church with due penance, and those who after abjuration relapsed, were to be abandoned to the secular arm for fitting punishment.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origmonth=,|origdate=, and|month=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Kirsch, Jonathan. The Grand Inquisitors Manual: A History of Terror in the Name of God. HarperOne. ISBN 0-06-081699-6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|origmonth=(help) - ^ Directorium Inquisitorum, edition of 1578, Book 3, pg. 137, column 1. Online in the Cornell University Collection; retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ^ Stokes, Adrian Durham (2002) [1955]. Michelangelo: a study in the nature of art. Routledge classics (2 ed.). Routledge. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-415-26765-6. Retrieved 2009-11-26.

Ludovico is so immediately settled in heaven by the poet that some commentators have divined that Michelangel is voicing heresy, that is to say, the denial of purgatory.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ Erasmus, the arch-Humanist of the Renaissance, came under suspicion of heresy, see

Olney, Warren (2009). Desiderius Erasmus; Paper Read Before the Berkeley Club, March 18, 1920. BiblioBazaar. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-113-40503-6. Retrieved 2009-11-26.

Thomas More, in an elaborate defense of his friend, written to a cleric who accused Erasmus of heresy, seems to admit that Erasmus was probably the author of Julius.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ Vidmar, John C. (2005). The Catholic Church Through the Ages. New York: Paulist Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-8091-4234-7.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ Soergel, Philip M. (1993). Wondrous in His Saints: Counter Reformation Propaganda in Bavaria. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 239. ISBN 0-520-08047-5.

- ^ Page of the painting at Prado Museum.

- ^ Henry Charles Lea, A History of the Inquisition of Spain, vol. 3, Book 8

- ^

Saraiva, António José; Salomon, Herman Prins; Sassoon, I. S. D (2001) [First published in Portuguese in 1969]. The Marrano Factory: the Portuguese Inquisition and its New Christians 1536-1765. Brill. p. 102. ISBN 978-90-04-12080-8. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help); Unknown parameter|firstn=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|lastn=ignored (help) - ^ The Galileo Project | Christianity|The Inquisition

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia

- ^

Compare Haydon, Colin (1993). Anti-Catholicism in eighteenth-century England, c. 1714-80: a political and social study. Studies in imperialism. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-7190-2859-0. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

The popular fear of Popery focused on the persecution of heretics by the Catholics. It was generally assumed that, whenever it was in their power, Papists would extirpate heresy by force, seeing it as a religious duty. History seemed to show this all too clearly. [...] The Inquisition had suppressed, and continued to check, religious dissent in Spain. Papists, and most of all, the Pope, delighted in the slaughter of heretics. 'I most firmly believed when I was as boy', William Cobbett [born 1763], coming originally from rural Surrey, recalled, 'that the Pope was a prodigious woman, dressed in a dreadful robe, which had been made red by being dipped in the blood of Protestants'.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help)

Bibliography

- Adler, E. N. (1901). "Auto de fe and Jew". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 13 (3). University of Pennsylvania Press: 392–437. doi:10.2307/1450541. JSTOR 1450541.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Edward Burman, The Inquisition: The Hammer of Heresy (Sutton Publishers, 2004) ISBN 0-7509-3722-X

- A new edition of a book first published in 1984, a general history based on the main primary sources.

- Foxe, John (1997) [1563]. Chadwick, Harold J. (ed.). The new Foxe's book of martyrs/John Foxe; rewritten and updated by Harold J. Chadwick. Bridge-Logos. ISBN 0-88270-672-1.

- Henry Kamen, The Spanish Inquisition: A Historical Revision. (Yale University Press, 1999); ISBN 0-300-07880-3

- This revised edition of his 1965 original contributes to the understanding of the Spanish Inquisition in its local context.

- Edward M. Peters, Inquisition (University of California Press, 1989); ISBN 0-520-06630-8

- Parker, Geoffrey (1982). "Some Recent Work on the Inquisition in Spain and Italy". Journal of Modern History. 54 (3).

- Cecil & Irene Roth, A history of the Marranos, Sepher-Hermon Press, 1974.

- William Thomas Walsh, Characters of the Inquisition (TAN Books and Publishers, Inc, 1940/97); ISBN 0-89555-326-0

- Ludovico a Paramo, De Origine et Progressu Sanctae Inquisitionis (1598).

- J. Baker, History of the Inquisition (1736).

- R. Cappa, La Inquisicion Espanola (1888).

- Genaro Garcia, Autos de fe de la Inquisicion de Mexico (1910).

- F. Garau, La Fee Triunfante (1691-reprinted 1931).

- Given, James B Inquisition and Medieval Society New York, Cornell University Press, 2001

- Henry Charles Lea, A History of the Inquisition of Spain (4 volumes), (New York and London, 1906–7).

- Juan Antonio Llorente, Historia Critica de la Inquisicion de Espana

- J. Marchant, A Review of the Bloody Tribunal (1770).

- J.M. Marin, Procedimientos de la Inquisicion (2 volumes), (1886).

- Antonio Puigblanch, La Inquisición sin máscara (Cádiz, 1811–1813). [The Inquisition Unmasked (London, 1816)]

- V. Vignau, Catalogo... de la Inquisicion de Toledo (1903).

- W.T. Walsh, Isabella of Spain (1931).

- Simon Whitechapel, Flesh Inferno: Atrocities of Torquemada and the Spanish Inquisition (Creation Books, 2003); ISBN 1-84068-105-5

- "A good example of how uncritical acceptance of disjointed historical data helps inform contemporary notions of the black legend"[This quote needs a citation]

- Paz y Mellia, Antonio (1914). Catalogo Abreviado de Papeles de Inquisicion (in in Spanish). Madrid: Tip. de la Revista de arch., bibl. y museos.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Sir Alexandr G. Cardew, A Short History of the Inquisition (1933).

- Warren H. Carroll, Isabel: the Catholic Queen Front Royal, Virginia, 1991 (Christendom Press)

- G. G. Coulton, The Inquisition (1929).

- Ramon de Vilana Perlas, La Verdadera Practica Apostolica de el S. Tribunal de la Inquisicion (1735).

- A. Herculano, Historia da Origem e Estabelecimento da Inquisicao em Portugal (English translation, 1926).

- H.B. Piazza, A Short and True Account of the Inquisition and its Proceeding (1722).

- L. Tanon, Histoire des Tribunaux de l'Inquisition (1893).

- Twiss, Miranda (2002). The Most Evil Men And Women In History. Michael O'Mara Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85479-488-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|month=,|coauthors=, and|editorn=(help) - Emile van der Vekene: Bibliotheca bibliographica historiae sanctae inquisitionis. Bibliographisches Verzeichnis des gedruckten Schrifttums zur Geschichte und Literatur der Inquisition. Vol. 1–3. Topos-Verlag, Vaduz 1982–1992, ISBN 3-289-00272-1, ISBN 3-289-00578-X (7110 titles on the subject "Inquisition")

- Emile van der Vekene: La Inquisición en grabados originales. Exposición realizada con fondos de la colección Emile van der Vekene de la Universidad San Pablo-CEU, Aranjuez, 4-26 de Mayo de 2005, Madrid: Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, 2005. ISBN 84-96144-86-0

Online works

- Ludwig von Pastor, History of the Popes from the Close of the Middle Ages; Drawn from the Secret Archives of the Vatican and other original sources, 40 vols. St. Louis,

- Joseph de Maistre, tr. John Fletcher, Letters on the Spanish Inquisition, London: Printed by W. Hughes, 1838 (composed 1815): late defense of the Inquisition by the principal author of the Counter-Enlightenment.

- Sister Antoinette Marie Pratt, A.M., The attitude of the Catholic Church towards witchcraft and the allied practices of sorcery and magic, A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Philosophy of The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C. June 1915, reprinted 1982, New York: AMS Press; ISBN 0-404-18429-4.

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (December 2010) |

- The Inquisition by Jewish Virtual Library

- Frequently Asked Questions About the Inquisition by James Hannam

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). Encyclopedia Americana.

Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). Encyclopedia Americana. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)- The Secret Files of The Inquistion. PBS

- "The Immeasurable Curiousity of Edward Peters", p.4 as found in the Pennsylvania Gazzette, a publication of the University of Pennsylvania

- Bradley, Gerard. "One Cheer for Inquisitions". Catholic Dossier. Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2008-11-06.: online copy of a column by a professor of law at the University of Notre Dame

- Scholarly studies including Lea's History

- Jewish Virtual Library on the Spanish Inquisition

- Galileo Project: Christianity: Inquisition

- Spanish Inquisition (1478-1813) (in Spanish language)

- Clandestine Judaism in the Shadow of the Inquisition, Dr. Rivkah Shafek Lissak

- The history of the inquisition of Spain

- Maris, Yves. "Cathars: Cathar philosophy". Chemis cathares. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - L. D. Barnett, "Two Documents of the Inquisition", in The Jewish Quarterly Review, New Ser., Vol. 15, No. 2 (Oct., 1924), pp. 213-239

- Inquisition against the Jews 1481-1834 (from Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971)