Speed of light

Sunlight takes about 8 minutes, 19 seconds to reach Earth | |

| Exact values | |

|---|---|

| metres per second | 299,792,458 |

| Planck units | 1 |

| Approximate values | |

| kilometres per second | 300,000 |

| kilometres per hour | 1,079 million |

| miles per second | 186,000 |

| miles per hour | 671 million |

| astronomical units per day | 173 |

| Approximate light signal travel times | |

| Distance | Time |

| one foot | 1.0 ns |

| one metre | 3.3 ns |

| one kilometre | 3.3 μs |

| one statute mile | 5.4 μs |

| from geostationary orbit to Earth | 119 ms |

| the length of Earth's equator | 134 ms |

| from Moon to Earth | 1.3 s |

| from Sun to Earth (1 AU) | 8.3 min |

| one parsec | 3.26 years |

| from Proxima Centauri to Earth | 4.24 years |

| from Alpha Centauri to Earth | 4.37 years |

| from the nearest galaxy (the Canis Major Dwarf Galaxy) to Earth | 25,000 years |

| across the Milky Way | 100,000 years |

| from the Andromeda Galaxy to Earth | 2.5 million years |

The speed of light, usually denoted by c, is a physical constant important in many areas of physics. Light and all other forms of electromagnetic radiation always travel at this speed in empty space (vacuum), regardless of the motion of the source or the inertial frame of reference of the observer. Its value is exactly 299,792,458 metres per second[1] (approximately 186,282 miles per second). In the theory of relativity, c interrelates space and time, and appears in the famous equation of mass–energy equivalence E = mc2.[2] It is the speed of all massless particles and associated fields in vacuum, and it is predicted by the current theory to be the speed of gravity and of gravitational waves and an upper bound on the speed at which energy, matter, and information can travel.

The speed at which light propagates through transparent materials, such as glass or air, is less than c. The ratio between c and the speed v at which light travels in a material is called the refractive index n of the material (n = c / v). For example, for visible light the refractive index of glass is typically around 1.5, meaning that light in glass travels at c / 1.5 ≈ 200000 km/s; the refractive index of air for visible light is about 1.0003, so the speed of light in air is very close to c.

In most practical cases, light can be thought of as moving instantaneously, but for long distances and very sensitive measurements the finite speed of light has noticeable effects. In communicating with distant space probes, it can take minutes to hours for the message to get from Earth to the satellite and back. The light we see from stars left them many years ago, allowing us to study the history of the universe by looking at distant objects. The finite speed of light also limits the theoretical maximum speed of computers, since information must be sent within the computer chips and from chip to chip. Finally, the speed of light can be used with time of flight measurements to measure large distances to high precision.

Ole Rømer first demonstrated in 1676 that light travelled at a finite speed (as opposed to instantaneously) by studying the apparent motion of Jupiter's moon Io. In 1905, Albert Einstein postulated that the speed of light in vacuum was independent of the source or inertial frame of reference, and explored the consequences of that postulate by deriving the theory of special relativity and showing that the parameter c had relevance outside of the context of light and electromagnetism. After centuries of increasingly precise measurements, in 1975 the speed of light was known to be 299792458 m/s with a relative measurement uncertainty of 4 parts per billion. In 1983, the metre was redefined in the International System of Units (SI) as the distance travelled by light in vacuum in 1⁄299792458 of a second. As a result, the numerical value of c in metres per second is now fixed exactly by the definition of the metre.[3]

Numerical value, notation, and units

The speed of light in vacuum is usually denoted by c, for "constant" or the Latin [celeritas] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (meaning "swiftness"). Originally, the symbol V was used, introduced by James Clerk Maxwell in 1865. In 1856, Wilhelm Eduard Weber and Rudolf Kohlrausch used c for a constant later shown to equal √2 times the speed of light in vacuum. In 1894, Paul Drude redefined c with its modern meaning. Einstein used V in his original German-language papers on special relativity in 1905, but in 1907 he switched to c, which by then had become the standard symbol.[4][5]

Sometimes c is used for the speed of waves in any material medium, and c0 for the speed of light in vacuum.[6] This subscripted notation, which is endorsed in official SI literature,[3] has the same form as other related constants: namely, μ0 for the vacuum permeability or magnetic constant, ε0 for the vacuum permittivity or electric constant, and Z0 for the impedance of free space. This article uses c exclusively for the speed of light in vacuum.

In the International System of Units (SI), the metre is defined as the distance light travels in vacuum in 1⁄299792458 of a second. This definition fixes the speed of light in vacuum at exactly 299792458 m/s.[7][8][9] As a dimensional physical constant, the numerical value of c is different for different unit systems.[Note 1]

In branches of physics in which c appears often, such as in relativity, it is common to use systems of natural units of measurement in which c = 1.[11][12] Using these units, c does not appear explicitly because multiplication or division by 1 does not affect the result.

Fundamental role in physics

The speed at which light propagates in vacuum is independent both of the motion of the light source and of the inertial frame of reference of the observer.[Note 2] This invariance of the speed of light was postulated by Einstein in 1905, after being motivated by Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism and the lack of evidence for the luminiferous ether;[13] it has since been consistently confirmed by many experiments.[Note 3][12][14] The theory of special relativity explores the consequences of this invariance of c with the assumption that the laws of physics are the same in all inertial frames of reference.[15][16] One consequence is that c is the speed at which all massless particles and waves, including light, must travel.

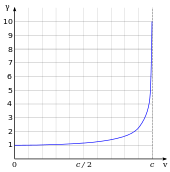

Special relativity has many counter-intuitive and experimentally verified implications.[17] These include the equivalence of mass and energy (E = mc2), length contraction (moving objects shorten),[Note 4] and time dilation (moving clocks run slower). The factor γ by which lengths contract and times dilate, is known as the Lorentz factor and is given by γ = (1 − v2/c2)−1/2, where v is the speed of the object. The difference of γ from 1 is negligible for speeds much slower than c, such as most everyday speeds—in which case special relativity is closely approximated by Galilean relativity—but it increases at relativistic speeds and diverges to infinity as v approaches c.

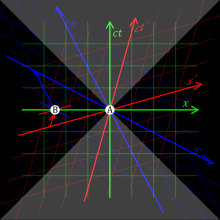

The results of special relativity can be summarized by treating space and time as a unified structure known as spacetime (with c relating the units of space and time), and requiring that physical theories satisfy a special symmetry called Lorentz invariance, whose mathematical formulation contains the parameter c.[20] Lorentz invariance is an almost universal assumption for modern physical theories, such as quantum electrodynamics, quantum chromodynamics, the Standard Model of particle physics, and general relativity. As such, the parameter c is ubiquitous in modern physics, appearing in many contexts that are unrelated to light. For example, general relativity predicts that c is also the speed of gravity and of gravitational waves.[21][22] In non-inertial frames of reference (gravitationally curved space or accelerated reference frames), the local speed of light is constant and equal to c, but the speed of light along a trajectory of finite length can differ from c, depending on how distances and times are defined.[23]

It is generally assumed that fundamental constants such as c have the same value throughout spacetime, meaning that they do not depend on location and do not vary with time. However, it has been suggested in various theories that the speed of light may have changed over time.[24][25] No conclusive evidence for such changes has been found, but they remain the subject of ongoing research.[26][27][28]

It also is generally assumed that the speed of light is isotropic, meaning that it has the same value regardless of the direction in which it is measured. Observations of the emissions from nuclear energy levels as a function of the orientation of the emitting nuclei in a magnetic field and of rotating optical resonators have put stringent limits on the possible anisotropy.[29][30]

Upper limit on speeds

According to special relativity, the energy of an object with rest mass m and speed v is given by γmc2, where γ is the Lorentz factor defined above. When v is zero, γ is equal to one, giving rise to the famous E = mc2 formula for mass-energy equivalence. Since the γ factor approaches infinity as v approaches c, it would take an infinite amount of energy to accelerate an object with mass to the speed of light. The speed of light is the upper limit for the speeds of objects with positive rest mass.[31]

More generally, it is normally impossible for information or energy to travel faster than c. One argument for this follows from the counter-intuitive implication of special relativity known as the relativity of simultaneity. If the spatial distance between two events A and B is greater than the time interval between them multiplied by c then there are frames of reference in which A precedes B, others in which B precedes A, and others in which they are simultaneous. As a result, if something were travelling faster than c relative to an inertial frame of reference, it would be travelling backwards in time relative to another frame, and causality would be violated.[Note 5][33] In such a frame of reference, an "effect" could be observed before its "cause". Such a violation of causality has never been recorded,[14] and would lead to paradoxes such as the tachyonic antitelephone.[34]

Faster-than-light observations and experiments

There are situations in which it may seem that matter, energy, or information travels at speeds greater than c, but they do not. For example, as is discussed in the propagation of light in a medium section below, many wave velocities can exceed c. For example, the phase velocity of X-rays through most glasses can routinely exceed c,[35] but such waves do not convey any information.[36]

If a laser beam is swept quickly across a distant object, the spot of light can move faster than c, although the initial movement of the spot is delayed because of the time it takes light to get to the distant object at the speed c. However, the only physical entities that are moving are the laser and its emitted light, which travels at the speed c from the laser to the various positions of the spot. Similarly, a shadow projected onto a distant object can be made to move faster than c, after a delay in time.[37] In neither case does any matter, energy, or information travel faster than light.[38] The rate of change in the distance between two objects in a frame of reference with respect to which both are moving (their closing speed) may have a value in excess of c. However, this does not represent the speed of any single object as measured in a single inertial frame.[38]

Certain quantum effects appear to be transmitted instantaneously and therefore faster than c, as in the EPR paradox. An example involves the quantum states of two particles that can be entangled. Until either of the particles is observed, they exist in a superposition of two quantum states. If the particles are separated and one particle's quantum state is observed, the other particle's quantum state is determined instantaneously (i.e., faster than light could travel from one particle to the other). However, it is impossible to control which quantum state the first particle will take on when it is observed, so information cannot be transmitted in this manner.[38][39]

Another quantum effect that predicts the occurrence of faster-than-light speeds is called the Hartman effect; under certain conditions the time needed for a virtual particle to tunnel through a barrier is constant, regardless of the thickness of the barrier.[40][41] This could result in a virtual particle crossing a large gap faster-than-light. However, no information can be sent using this effect.[42]

So-called superluminal motion is seen in certain astronomical objects,[43] such as the relativistic jets of radio galaxies and quasars. However, these jets are not moving at speeds in excess of the speed of light: the apparent superluminal motion is a projection effect caused by objects moving near the speed of light and approaching Earth at a small angle to the line of sight: since the light which was emitted when the jet was farther away took longer to reach the Earth, the time between two successive observations corresponds to a longer time between the instants at which the light rays were emitted.[44]

In models of the expanding universe, the farther galaxies are from each other, the faster they drift apart. This receding is not due to motion through space, but rather to the expansion of space itself.[38] For example, galaxies far away from Earth appear to be moving away from the Earth with a speed proportional to their distances. Beyond a boundary called the Hubble sphere, the rate at which their distance from Earth increases becomes greater than the speed of light.[45]

Propagation of light

In classical physics, light is described as a type of electromagnetic wave. The classical behaviour of the electromagnetic field is described by Maxwell's equations, which predict that the speed c with which electromagnetic waves (such as light) propagate through the vacuum is related to the electric constant ε0 and the magnetic constant μ0 by the equation c = 1/√ε0μ0.[46] In modern quantum physics, the electromagnetic field is described by the theory of quantum electrodynamics (QED). In this theory, light is described by the fundamental excitations (or quanta) of the electromagnetic field, called photons. In QED, photons are massless particles and thus, according to special relativity, they travel at the speed of light in vacuum.

Extensions of QED in which the photon has a mass have been considered. In such a theory, its speed would depend on its frequency, and the invariant speed c of special relativity would then be the upper limit of the speed of light in vacuum.[23] No variation of the speed of light with frequency has been observed in rigorous testing,[47][48][49] putting stringent limits on the mass of the photon. The limit obtained depends on the model used: if the massive photon is described by Proca theory,[50] the experimental upper bound for its mass is about 10−57 grams;[51] if photon mass is generated by a Higgs mechanism, the experimental upper limit is less sharp, m ≤ 10−14 eV/c2 [50] (roughly 2 × 10−47 g).

Another reason for the speed of light to vary with its frequency would be the failure of special relativity to apply to arbitrarily small scales, as predicted by some proposed theories of quantum gravity. In 2009, the observation of the spectrum of gamma-ray burst GRB 090510 did not find any difference in the speeds of photons of different energies, confirming that Lorentz invariance is verified at least down to the scale of the Planck length (lP = √ħG/c3 ≈ 1.6163×10−35 m) divided by 1.2.[52]

In a medium

In a medium, light usually does not propagate at a speed equal to c; further, different types of light wave will travel at different speeds. The speed at which the individual crests and troughs of a plane wave (a wave filling the whole space, with only one frequency) propagates is called the phase velocity vp. An actual physical signal with a finite extent (a pulse of light) travels at a different speed. The largest part of the pulse travels at the group velocity vg, and its earliest part travels at the front velocity vf.

The phase velocity is important in determining how a light wave travels through a material or from one material to another. It is often represented in terms of a refractive index. The refractive index of a material is defined as the ratio of c to the phase velocity vp in the material: larger indices of refraction indicate lower speeds. The refractive index of a material may depend on the light's frequency, intensity, polarization, or direction of propagation; in many cases, though, it can be treated as a material-dependent constant. The refractive index of air is approximately 1.0003.[53] Denser media, such as water,[54] glass,[55] and diamond,[56] have refractive indexes of around 1.3, 1.5 and 2.4 respectively for visible light.

In transparent materials, the refractive index generally is greater than 1, meaning that the phase velocity is less than c. In other materials, it is possible for the refractive index to become smaller than 1 for some frequencies; in some exotic materials it is even possible for the index of refraction to become negative.[57] The requirement that causality is not violated implies that the real and imaginary parts of the dielectric constant of any material, corresponding respectively to the index of refraction and to the attenuation coefficient, are linked by the Kramers–Kronig relations.[58] In practical terms, this means that in a material with refractive index less than 1, the absorption of the wave is so quick that no signal can be sent faster than c.

A pulse with different group and phase velocities (which occurs if the phase velocity is not the same for all the frequencies of the pulse) smears out over time, a process known as dispersion. Certain materials have an exceptionally low (or even zero) group velocity for light waves, a phenomenon called slow light, which has been confirmed in various experiments.[59][60][61][62] The opposite, group velocities exceeding c, has also been shown in experiment.[63] It should even be possible for the group velocity to become infinite or negative, with pulses travelling instantaneously or backwards in time.[64]

None of these options, however, allow information to be transmitted faster than c. It is impossible to transmit information with a light pulse any faster than the speed of the earliest part of the pulse (the front velocity). It can be shown that this is (under certain assumptions) always equal to c.[64]

It is possible for a particle to travel through a medium faster than the phase velocity of light in that medium (but still slower than c). When a charged particle does that in an electrical insulator, the electromagnetic equivalent of a shock wave, known as Cherenkov radiation, is emitted.[65]

Practical effects of finiteness

The finiteness of the speed of light has implications for various sciences and technologies. In some cases, it is a hindrance: for example, c, being the upper limit of the speed with which signals can be sent, provides a theoretical upper limit for the operating speed of microprocessors.[66] On the other hand, some techniques depend on it, for example in distance measurements.

The speed of light is of relevance to communications. For example, given the equatorial circumference of the Earth is about 40,075 km and c about 300,000 km/s, the theoretical shortest time for a piece of information to travel half the globe along the surface is about 67 milliseconds. When light is travelling around the globe in an optical fibre, the actual transit time is longer, in part because the speed of light is slower by about 35% in an optical fibre, depending on its refractive index n.[67] Furthermore, straight lines rarely occur in global communications situations, and delays are created when the signal passes through an electronic switch or signal regenerator.[68]

Another consequence of the finite speed of light is that communications between the Earth and spacecraft are not instantaneous. There is a brief delay from the source to the receiver, which becomes more noticeable as distances increase. This delay was significant for communications between ground control and Apollo 8 when it became the first manned spacecraft to orbit the Moon: for every question, the ground control station had to wait at least three seconds for the answer to arrive.[69] The communications delay between Earth and Mars can vary between five and twenty minutes depending upon the relative positions of the two planets. As a consequence of this, if a robot on the surface of Mars were to encounter a problem, its human controllers would not be aware of it until at least five minutes, and possibly up to twenty minutes, later; it would then take a further five to twenty minutes for instructions to travel from Earth to Mars.

The speed of light can also be of concern over very short distances. In supercomputers, the speed of light imposes a limit on how quickly data can be sent between processors. If a processor operates at 1 gigahertz, a signal can only travel a maximum of about 30 centimetres (1 ft) in a single cycle. Processors must therefore be placed close to each other to minimize communication latencies; this can cause difficulty with cooling. If clock frequencies continue to increase, the speed of light will eventually become a limiting factor for the internal design of single chips.[66]

Distance measurement

Radar systems measure the distance to a target by the time it takes a radio-wave pulse to return to the radar antenna after being reflected by the target: the distance to the target is half the round-trip transit time multiplied by the speed of light. A Global Positioning System (GPS) receiver measures its distance to GPS satellites based on how long it takes for a radio signal to arrive from each satellite, and from these distances calculates the receiver's position. Because light travels about 300,000 kilometres (186,000 miles) in one second, these measurements of small fractions of a second must be very precise. The Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment, radar astronomy and the Deep Space Network determine distances to the Moon,[70] planets[71] and spacecraft,[72] respectively, by measuring round-trip transit times.

Astronomy

The finite speed of light is important in astronomy. Due to the vast distances involved, it can take a very long time for light to travel from its source to Earth. For example, it has taken 13 billion (13×109) years for light to travel to Earth from the faraway galaxies viewed in the Hubble Ultra Deep Field images.[73][74] Those photographs, taken today, capture images of the galaxies as they appeared 13 billion years ago, when the universe was less than a billion years old.[73] The fact that more distant objects appear to be younger, due to the finite speed of light, allows astronomers to infer the evolution of stars, of galaxies, and of the universe itself.

Astronomical distances are sometimes expressed in light-years, especially in popular science publications and media.[75] A light-year is the distance light travels in one year, around 9461 billion kilometres, 5879 billion miles, or 0.3066 parsecs. Proxima Centauri, the closest star to Earth after the Sun, is around 4.2 light-years away.[76]

Measurement

There are different ways to determine the value of c. One way is to measure the actual speed at which light waves propagate, which can be done in various astronomical and earth-based setups. However, it is also possible to determine c from other physical laws where it appears, for example, by determining the values of the electromagnetic constants ε0 and μ0 and using their relation to c. Historically, the most precise results have been obtained by separately determining the frequency and wavelength of a lightwave, with their product equaling c.

In 1983 the metre was defined as "the length of the path travelled by light in vacuum during a time interval of 1⁄299,792,458 of a second",[77] fixing the value of the speed of light at 299792458 m/s by definition, as described below. Consequently, precision measurements of the speed of light yield a precise realization of the metre rather than a precise value of c.

Astronomical measurements

Outer space is a natural setting for measuring the speed of light because of its large scale and nearly perfect vacuum. Typically, one measures the time needed for light to traverse some reference distance in the solar system, such as the radius of the Earth's orbit. Historically, such measurements could be made fairly accurately, compared to how accurately the length of the reference distance is known in Earth-based units. It is customary to express the results in astronomical units (AU) per day. An astronomical unit is approximately the average distance between the Earth and Sun; it is not based on the International System of Units.[Note 6] Because the AU determines an actual length, and is not based upon time-of-flight like the SI units, modern measurements of the speed of light in astronomical units per day can be compared with the defined value of c in the International System of Units.

Ole Christensen Rømer used an astronomical measurement to make the first quantitative estimate of the speed of light.[80][81] When measured from Earth, the periods of moons orbiting a distant planet are shorter when the Earth is approaching the planet than when the Earth is receding from it. The distance travelled by light from the planet (or its moon) to Earth is shorter when the Earth is at the point in its orbit that is closest to its planet than when the Earth is at the farthest point in its orbit, the difference in distance being the diameter of the Earth's orbit around the Sun. The observed change in the moon's orbital period is actually the difference in the time it takes light to traverse the shorter or longer distance. Rømer observed this effect for Jupiter's innermost moon Io and deduced that light takes 22 minutes to cross the diameter of the Earth's orbit.

Another method is to use the aberration of light, discovered and explained by James Bradley in the 18th century.[82] This effect results from the vector addition of the velocity of light arriving from a distant source (such as a star) and the velocity of its observer (see diagram on the right). A moving observer thus sees the light coming from a slightly different direction and consequently sees the source at a position shifted from its original position. Since the direction of the Earth's velocity changes continuously as the Earth orbits the Sun, this effect causes the apparent position of stars to move around. From the angular difference in the position of stars (maximally 20.5 arcseconds)[83] it is possible to express the speed of light in terms of the Earth's velocity around the Sun, which with the known length of a year can be easily converted to the time needed to travel from the Sun to the Earth. In 1729, Bradley used this method to derive that light travelled 10,210 times faster than the Earth in its orbit (the modern figure is 10,066 times faster) or, equivalently, that it would take light 8 minutes 12 seconds to travel from the Sun to the Earth.[82]

Nowadays, the "light time for unit distance"—the inverse of c, expressed in seconds per astronomical unit—is measured by comparing the time for radio signals to reach different spacecraft in the Solar System, with their position calculated from the gravitational effects of the Sun and various planets. By combining many such measurements, a best fit value for the light time per unit distance is obtained. As of 2009[update], the best estimate, as approved by the International Astronomical Union (IAU), is:[84][85]

- light time for unit distance: 499.004783836(10) s

- c = 0.00200398880410(4) AU/s = 173.144632674(3) AU/day.

The relative uncertainty in these measurements is 0.02 parts per billion (2×10−11), equivalent to the uncertainty in Earth-based measurements of length by interferometry.[86][Note 7] Since the metre is defined to be the length travelled by light in a certain time interval, the measurement of the light time for unit distance can also be interpreted as measuring the length of an AU in metres.[Note 8]

Time of flight techniques

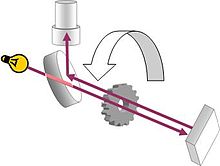

A method of measuring the speed of light is to measure the time needed for light to travel to a mirror at a known distance and back. This is the working principle behind the Fizeau–Foucault apparatus developed by Hippolyte Fizeau and Léon Foucault.

The setup as used by Fizeau consists of a beam of light directed at a mirror 8 kilometres (5 mi) away. On the way from the source to the mirror, the beam passes through a rotating cogwheel. At a certain rate of rotation, the beam passes through one gap on the way out and another on the way back, but at slightly higher or lower rates, the beam strikes a tooth and does not pass through the wheel. Knowing the distance between the wheel and the mirror, the number of teeth on the wheel, and the rate of rotation, the speed of light can be calculated.[87]

The method of Foucault replaces the cogwheel by a rotating mirror. Because the mirror keeps rotating while the light travels to the distant mirror and back, the light is reflected from the rotating mirror at a different angle on its way out than it is on its way back. From this difference in angle, the known speed of rotation and the distance to the distant mirror the speed of light may be calculated.[88]

Nowadays, using oscilloscopes with time resolutions of less than one nanosecond, the speed of light can be directly measured by timing the delay of a light pulse from a laser or an LED reflected from a mirror. This method is less precise (with errors of the order of 1%) than other modern techniques, but it is sometimes used as a laboratory experiment in college physics classes.[89][90][91]

Electromagnetic constants

An option for measuring c that does not directly depend on the propagation of electromagnetic waves is to use relation between c and the vacuum permittivity ε0 vacuum permeability μ0 established by Maxwell theory: c2 = 1/(ε0μ0). The vacuum permittivity may be determined by measuring the capacitance and dimensions of a capacitor, whereas the value of the vacuum permeability is fixed at exactly 4π×10−7 H*m-1 through the definition of the ampere. Rosa and Dorsey used this method in 1907 to find a value of 299710±22 km/s.[92][93]

Cavity resonance

Another way to measure the speed of light is to independently measure the frequency f and wavelength λ of an electromagnetic wave in vacuum. The value of c can then be found by using the relation c = fλ. One option is to measure the resonance frequency of a cavity resonator. If the dimensions of the resonance cavity are also known, these can be used determine the wavelength of the wave. In 1946, Louis Essen and A.C. Gordon-Smith establish the frequency for a variety of normal modes of microwaves of a microwave cavity of precisely known dimensions. The dimensions were established to an accuracy of about ±0.8 μm using gauges calibrated by interferometry.[92] As the wavelength of the modes was known from the geometry of the cavity and from electromagnetic theory, knowledge of the associated frequencies enabled a calculation of the speed of light.[92][94]

The Essen–Gordon-Smith result, 299792±9 km/s, was substantially more precise than those found by optical techniques.[92] By 1950, repeated measurements by Essen established a result of 299792.5±3.0 km/s.[95]

A household demonstration of this technique is possible, using a microwave oven and food such as marshmallows or margarine: if the turntable is removed so that the food does not move, it will cook the fastest at the antinodes (the points at which the wave amplitude is the greatest), where it will begin to melt. The distance between two such spots is half the wavelength of the microwaves; by measuring this distance and multiplying the wavelength by the microwave frequency (usually displayed on the back of the oven, typically 2450 MHz), the value of c can be calculated, "often with less than 5% error".[96][97]

Interferometry

Interferometry is another method to find the wavelength of electromagnetic radiation for determining the speed of light.[98] A coherent beam of light (e.g. from a laser), with a known frequency (f), is split to follow two paths and then recombined. By adjusting the path length while observing the interference pattern and carefully measuring the change in path length, the wavelength of the light (λ) can be determined. The speed of light is then calculated using the equation c = λf.

Before the advent of laser technology, coherent radio sources were used for interferometry measurements of the speed of light.[99] However interferometric determination of wavelength becomes less precise with wavelength and the experiments were thus limited in precision by the long wavelength (~0.4 cm) of the radiowaves. The precision can be improved by using light with a shorter wavelength, but then it becomes difficult to directly measure the frequency of the light. One way around this problem is to start with a low frequency signal of which the frequency can be precisely measured, and from this signal progressively synthesize higher frequency signals whose frequency can then be linked to the original signal. A laser can then be locked to the frequency, and its wavelength can be determined using interferometry.[100] This technique was due to a group at the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) (which later became NIST). They used it in 1972 to measure the speed of light in vacuum with a fractional uncertainty of 3.5×10−9.[100][101]

History

| 1675 | Rømer and Huygens, moons of Jupiter | 220000[81][102] |

| 1729 | James Bradley, aberration of light | 301000[87] |

| 1849 | Hippolyte Fizeau, toothed wheel | 315000[87] |

| 1862 | Léon Foucault, rotating mirror | 298000±500[87] |

| 1907 | Rosa and Dorsey, EM constants | 299710±30[92][93] |

| 1926 | Albert Michelson, rotating mirror | 299796±4[103] |

| 1950 | Essen and Gordon-Smith, cavity resonator | 299792.5±3.0[95] |

| 1958 | K.D. Froome, radio interferometry | 299792.50±0.10[99] |

| 1972 | Evenson et al., laser interferometry | 299792.4562±0.0011[101] |

| 1983 | 17th CGPM, definition of the metre | 299792.458 (exact)[77] |

Until the early modern period, it was not known whether light travelled instantaneously or at a very fast finite speed. The first extant recorded examination of this subject was in ancient Greece. Empedocles was the first to claim that the light has a finite speed.[104] He maintained that light was something in motion, and therefore must take some time to travel. Aristotle argued, to the contrary, that "light is due to the presence of something, but it is not a movement".[105] Euclid and Ptolemy advanced the emission theory of vision, where light is emitted from the eye, thus enabling sight. Based on that theory, Heron of Alexandria argued that the speed of light must be infinite because distant objects such as stars appear immediately upon opening the eyes.

Early Islamic philosophers initially agreed with the Aristotelian view that light had no speed of travel. In 1021, Alhazen (Ibn al-Haytham) published the Book of Optics, in which he presented a series of arguments dismissing the emission theory in favour of the now accepted intromission theory of vision, in which light moves from an object into the eye.[106] This led Alhazen to propose that light must have a finite speed,[105][107][108] and that the speed of light is variable, decreasing in denser bodies.[108][109] He argued that light is substantial matter, the propagation of which requires time, even if this is hidden from our senses.[110]

Also in the 11th century, Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī agreed that light has a finite speed, and observed that the speed of light is much faster than the speed of sound.[111] Roger Bacon argued that the speed of light in air was not infinite, using philosophical arguments backed by the writing of Alhazen and Aristotle.[112][113] In the 1270s, Witelo considered the possibility of light travelling at infinite speed in vacuum, but slowing down in denser bodies.[114]

In the early 17th century, Johannes Kepler believed that the speed of light was infinite, since empty space presents no obstacle to it. René Descartes argued that if the speed of light were finite, the Sun, Earth, and Moon would be noticeably out of alignment during a lunar eclipse. Since such misalignment had not been observed, Descartes concluded the speed of light was infinite. Descartes speculated that if the speed of light were found to be finite, his whole system of philosophy might be demolished.[105]

First measurement attempts

In 1629, Isaac Beeckman proposed an experiment in which a person observes the flash of a cannon reflecting off a mirror about one mile (1.6 km) away. In 1638, Galileo Galilei proposed an experiment, with an apparent claim to having performed it some years earlier, to measure the speed of light by observing the delay between uncovering a lantern and its perception some distance away. He was unable to distinguish whether light travel was instantaneous or not, but concluded that if it weren't, it must nevertheless be extraordinarily rapid.[115][116] Galileo's experiment was carried out by the Accademia del Cimento of Florence, Italy, in 1667, with the lanterns separated by about one mile, but no delay was observed. Based on the modern value of the speed of light, the actual delay in this experiment is about 11 microseconds.

The first quantitative estimate of the speed of light was made in 1676 by Rømer (see Rømer's determination of the speed of light).[80][81] From the observation that the periods of Jupiter's innermost moon Io appeared to be shorter when the Earth was approaching Jupiter than when receding from it, he concluded that light travels at a finite speed, and estimated that it takes light 22 minutes to cross the diameter of Earth's orbit. Christiaan Huygens combined this estimate with an estimate for the diameter of the Earth's orbit to obtain an estimate of speed of light of 220000 km/s, 26% lower than the actual value.[102]

In his 1704 book Opticks, Isaac Newton reported Rømer's calculations of the finite speed of light and gave a value of "seven or eight minutes" for the time taken for light to travel from the Sun to the Earth (the modern value is 8 minutes 19 seconds).[117] Newton queried whether Rømer's eclipse shadows were coloured; hearing that they weren't, he concluded the different colours travelled at the same speed. In 1729, James Bradley discovered the aberration of light.[82] From this effect he determined that light must travel 10,210 times faster than the Earth in its orbit (the modern figure is 10,066 times faster) or, equivalently, that it would take light 8 minutes 12 seconds to travel from the Sun to the Earth.[82]

19th and early 20th century

In the 19th century Hippolyte Fizeau developed a method to determine the speed of light based on time-of-flight measurements on Earth and reported a value of 315000 km/s. His method was improved upon by Léon Foucault who obtained a value of 298000 km/s in 1862.[87] In the year 1856, Wilhelm Eduard Weber and Rudolf Kohlrausch measured the ratio of the electromagnetic and electrostatic units of charge, 1/√ε0μ0, by discharging a Leyden jar, and found that its numerical value was very close to the speed of light as measured directly by Fizeau. The following year Gustav Kirchoff calculated that an electric signal in a resistanceless wire travels along the wire at this speed.[118] In the early 1860s, Maxwell showed that according to the theory of electromagnetism which he was working on, that electromagnetic waves propagate in empty space[119][120][121] at a speed equal to the above Weber/Kohrausch ratio, and drawing attention to the numerical proximity of this value to the speed of light as measured by Fizeau, he proposed that light is in fact an electromagnetic wave.[122]

It was thought at the time that empty space was filled with a background medium called the luminiferous aether in which the electromagnetic field existed. Some physicists thought that this aether acted as an absolute reference frame for all physics and therefore it should be possible to measure the motion of the Earth with respect to this medium. Beginning in the 1880s several experiments were performed to try to detect this motion, the most famous of which is the experiment performed by Albert Michelson and Edward Morley in 1887.[123] The detected motion was always less than the observational error. Modern experiments indicate that the two-way speed of light is isotropic (the same in every direction) to within 6 nanometers per second.[124] Because of this experiment Hendrik Lorentz proposed that the motion of the apparatus through the aether may cause the apparatus to contract along its length in the direction of motion, by a factor such as to ensure that there is no interference fringes detected by the interferometer. Based on Lorentz's theory, Poincare concluded in 1904 that the speed of light is a limiting factor in dynamics.[125] In 1905 Einstein proposed that the speed of light in vacuum, measured by a non-accelerating observer, is independent of the motion of the source or observer. Using this and the principle of relativity as a basis he derived the special theory of relativity, in which the speed of light in vacuum c featured as a fundamental parameter, also appearing in contexts unrelated to light.[126]

Increased accuracy of c and redefinition of the metre

In the second half of the 20th century much progress was made in increasing the accuracy of measurements of the speed of light, first by cavity resonance techniques and later by laser interferometer techniques. In 1972, using the latter method, a group at NBS in Boulder, Colorado determined the speed of light in vacuum to be c = 299792456.2±1.1 m/s. This was 100 times less uncertain than the previously accepted value. The remaining uncertainty was mainly related to the definition of the metre.[Note 9][101] Since similar experiments found comparable results for c, the 15th Conférence Générale des Poids et Mesures (CGPM) in 1975 recommended using the value 299792458 m/s for the speed of light.[129]

Because the previous definition was deemed inadequate for the needs of various experiments, the 17th CGPM in 1983 decided to redefine the metre.[130] The new (and current) definition reads: "The metre is the length of the path travelled by light in vacuum during a time interval of 1/299 792 458 of a second."[77] As a result of this definition, the value of the speed of light in vacuum is exactly 299792458 m/s[131][132] and has become a defined constant in the SI system of units.[9] Improved experimental techniques do not affect the value of the speed of light in SI units, but do result in a more precise realization of the metre.[133][134]

See also

Notes

- ^ The speed of light in imperial units and US units is based on an inch of exactly 2.54 cm and is exactly 186,282 miles, 698 yards, 2 feet, and 5+21⁄127 inches per second.[10]

- ^ However, the frequency of light can depend on the motion of the source relative to the observer due to the Doppler effect.

- ^ It is only possible to verify experimentally that the two-way speed of light (for example, from a source to a mirror and back again) is frame-independent, because it is impossible to measure the one-way speed of light (for example, from a source to a distant detector) without some convention as to how clocks at the source and at the detector should be synchronized. However, by adopting Einstein synchronization for the clocks, the one-way speed of light becomes equal to the two way speed of light by definition.

- ^ Whereas moving objects are measured to be shorter along the line of relative motion, they are also seen as being rotated. This effect, known as Terrell rotation, is due to the different times that light from different parts of the object takes to reach the observer.[18][19]

- ^ It is thought that the Scharnhorst effect does allow signals to travel slightly faster than c, but the special conditions in which this effect can occur prevent one from using this effect to violate causality.[32]

- ^ The astronomical unit is defined the radius of an unperturbed circular Newtonian orbit about the Sun of a particle having infinitesimal mass, moving with an angular frequency of 0.01720209895 radians (approximately 1⁄365.256898 of a revolution) per day.[78] It may be noted that the astronomical unit increases at a rate of about (15 ± 4) cm/yr, probably due to the changing mass of the Sun.[79] This unit has the advantage that the gravitational constant multiplied by the Sun's mass has a fixed, exact value in cubic astronomical units per day squared.

- ^ The value of the speed of light in astronomical units has a measurement uncertainty, unlike the value in SI units, because of the different definitions of the unit of length.

- ^ Nevertheless, at this degree of precision, the effects of general relativity must be taken into consideration when interpreting the length. The metre is considered to be a unit of proper length, whereas the AU is usually used as a unit of observed length in a given frame of reference. The values cited here follow the latter convention, and are TDB-compatible.[85]

- ^ Since 1960 the metre was defined as: "The metre is the length equal to 1650763.73 wavelengths in vacuum of the radiation corresponding to the transition between the levels 2p10 and 5d5 of the krypton 86 atom."[127] It was later discovered that this spectral line was not symmetric, which put a limit on the precision with which the definition could be realized in interferometry experiments.[128]

References

- ^ Penrose, R (2004). The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. Vintage Books. pp. 410–1. ISBN 9780679776314.

... the most accurate standard for the metre is conveniently defined so that there are exactly 299,792,458 of them to the distance travelled by light in a standard second, giving a value for the metre that very accurately matches the now inadequately precise standard metre rule in Paris.

- ^ Uzan, J-P; Leclercq, B (2008). The Natural Laws of the Universe: Understanding Fundamental Constants. Springer. pp. 43–4. ISBN 0387734546.

- ^ a b Le Système international d’unités [The International System of Units] (PDF) (in French and English) (9th ed.), International Bureau of Weights and Measures, 2019, p. 112, ISBN 978-92-822-2272-0

- ^ Gibbs, P (2004) [1997]. "Why is c the symbol for the speed of light?". Usenet Physics FAQ. University of California, Riverside. Archived from the original on 2009-11-17. Retrieved 2009-11-16.

- ^

Mendelson, KS (2006). "The story of c". American Journal of Physics. 74 (11): 995–997. doi:10.1119/1.2238887.

{{cite journal}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ See for example:

- Lide, DR (2004). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. CRC Press. pp. 2–9. ISBN 0849304857.

- Harris, JW (2002). Handbook of Physics. Springer. p. 499. ISBN 0-387-95269-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Whitaker, JC (2005). The Electronics Handbook. CRC Press. p. 235. ISBN 0849318890.

- Cohen, ER (2007). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry (3rd ed.). Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 184. ISBN 0854044337.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- ^

Sydenham, PH (2003). "Measurement of length". In Boyes, W (ed.). Instrumentation Reference Book (3rd ed.). Butterworth–Heinemann. p. 56. ISBN 0750671238.

... if the speed of light is defined as a fixed number then, in principle, the time standard will serve as the length standard ...

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ "CODATA value: Speed of Light in Vacuum". The NIST reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- ^ a b Jespersen, J; Fitz-Randolph, J; Robb, J (1999). From Sundials to Atomic Clocks: Understanding Time and Frequency (Reprint of National Bureau of Standards 1977, 2nd ed.). Courier Dover. p. 280. ISBN 0486409139.

- ^

Savard, J. "From Gold Coins to Cadmium Light". John Savard's Home Page. Archived from the original on 2009-11-14. Retrieved 2009-11-14.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^

Lawrie, ID (2002). "Appendix C: Natural units". A Unified Grand Tour of Theoretical Physics (2nd ed.). CRC Press. p. 540. ISBN 0750306041.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ a b

Hsu, L (2006). "Appendix A: Systems of units and the development of relativity theories". A Broader View of Relativity: General Implications of Lorentz and Poincaré Invariance (2nd ed.). World Scientific. pp. 427–8. ISBN 9812566511.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "Hsu" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^

Einstein, A (1905). "Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper" (PDF). Annalen der Physik (in German). 17: 890–921. English translation: Perrett, W; Jeffery, GB (tr.); Walker, J (ed.). "On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies". Fourmilab. Retrieved 2009-11-27.

{{cite web}}:|first3=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Zhang, YZ (1997). Special Relativity and Its Experimental Foundations. Advanced Series on Theoretical Physical Science. Vol. 4. World Scientific. pp. 172–3. ISBN 9810227493.

- ^ d'Inverno, R (1992). Introducing Einstein's Relativity. Oxford University Press. pp. 19–20. ISBN 0198596863.

- ^

Sriranjan, B (2004). "Postulates of the special theory of relativity and their consequences". The Special Theory to Relativity. PHI Learning. pp. 20 ff. ISBN 812031963X.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^

Roberts, T; Schleif, S; Dlugosz, JM (ed.) (2007). "What is the experimental basis of Special Relativity?". Usenet Physics FAQ. University of California, Riverside. Retrieved 2009-11-27.

{{cite web}}:|first3=has generic name (help) - ^ Terrell, J (1959). "Invisibility of the Lorentz Contraction". Physical Review. 116: 1041–5. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.116.1041.

- ^ Penrose, R (1959). "The Apparent Shape of a Relativistically Moving Sphere". Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 55: 137–9. doi:10.1017/S0305004100033776.

- ^ Hartle, JB (2003). Gravity: An Introduction to Einstein's General Relativity. Addison-Wesley. pp. 52–9. ISBN 9810227493.

- ^ Hartle, JB (2003). Gravity: An Introduction to Einstein's General Relativity. Addison-Wesley. p. 332. ISBN 9810227493.

- ^ The interpretation of observations on binary systems used to determine the speed of gravity is considered doubtful by some authors, leaving the experimental situation uncertain; see Schäfer, G; Brügmann, MH (2008). "Propagation of light in the gravitational filed of binary systems to quadratic order in Newton's gravitational constant: Part 3: 'On the speed-of-gravity controversy'". In Dittus, H; Lämmerzahl, C; Turyshev, SG (eds.). Lasers, clocks and drag-free control: Exploration of relativistic gravity in space. Springer. ISBN 3540343768.

- ^ a b Gibbs, P (1997) [1996]. Carlip, S (ed.). "Is The Speed of Light Constant?". Usenet Physics FAQ. University of California, Riverside. Archived from the original on 2009-11-17. Retrieved 2009-11-26.

- ^

Ellis, GFR; Uzan, J-P (2005). "'c' is the speed of light, isn't it?". American Journal of Physics. 73: 240–7. doi:10.1119/1.1819929. arXiv:gr-qc/0305099.

The possibility that the fundamental constants may vary during the evolution of the universe offers an exceptional window onto higher dimensional theories and is probably linked with the nature of the dark energy that makes the universe accelerate today.

- ^ An overview can be found in the dissertation of Mota, DF (2006). Variations of the fine structure constant in space and time. (PhD thesis). University of Cambridge. arXiv:astro-ph/0401631.

- ^ Uzan, J-P (2003). "The fundamental constants and their variation: observational status and theoretical motivations". Reviews of Modern Physics. 74: 403. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.75.403. arXiv:hep-ph/0205340.

- ^

Farrell, DJ; Dunning-Davies, J (2007). "The constancy, or otherwise, of the speed of light". In Ross, LV (ed.). New Research on Astrophysics, Neutron Stars and Galaxy Clusters. Nova Publishers. pp. 71ff. ISBN 1600211100.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Amelino-Camelia, G (2008). "Quantum Gravity Phenomenology". arXiv:0806.0339 [gr-qc].

- ^ Herrmann, S; Senger, A; Kovalchuk, E; Müller, H; Peters, A (2005). "Test of the isotropy of the speed of light using a continuously rotating optical resonator". Phys Rev Lett. 95: 150401. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.150401. arXiv:physics/0508097.

- ^ Lang, KR (1999). Astrophysical formulae (3rd ed.). Birkhäuser. p. 152. ISBN 3540296921.

- ^ Fowler, M (March 2008). "Notes on Special Relativity" (PDF). University of Virginia. p. 56. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ^ Liberati, S; Sonego, S; Visser, M (2002). "Faster-than-c signals, special relativity, and causality". Annals of Physics. 298: 167–85. doi:10.1006/aphy.2002.6233. arXiv:gr-qc/0107091.

- ^ Taylor, EF; Wheeler, JA (1992). Spacetime Physics. W. H. Freeman. pp. 74–5. ISBN 0716723271.

- ^ Tolman, RC (2009) [1917]. "Velocities greater than that of light". The Theory of the Relativity of Motion (Reprint ed.). BiblioLife. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-103-17233-7.

- ^ Hecht, E (1987). Optics (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley. p. 62. ISBN 0-201-11609-X.

- ^ Quimby, RS (2006). Photonics and lasers: an introduction. John Wiley and Sons. p. 9. ISBN 9780471719748.

- ^ Wertheim, M (2007-06-20). "The Shadow Goes". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- ^ a b c d Gibbs, P (1997). "Is Faster-Than-Light Travel or Communication Possible?". Usenet Physics FAQ. University of California, Riverside. Archived from the original on 2009-11-17. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ^ Sakurai, JJ (1994). T, S (ed.). Modern Quantum Mechanics (Revised ed.). Addison-Wesley. pp. 231–232. ISBN 0-201-53929-2.

- ^

Muga, JG; Mayato, RS; Egusquiza, IL, eds (2007). Time in Quantum Mechanics. Springer. p. 48. ISBN 3540734724.

{{cite book}}:|first3=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hernández-Figueroa, HE; Zamboni-Rached, M; Recami, E (2007). Localized Waves. Wiley Interscience. p. 26. ISBN 0470108851.

- ^ Wynne, K (2002). "Causality and the nature of information" (PDF). Optics Communications. 209: 84–100. doi:10.1016/S0030-4018(02)01638-3.

- ^ Rees, M (1966). "The Appearance of Relativistically Expanding Radio Sources". Nature. 211: 468. doi:10.1038/211468a0.

- ^ Chase, IP. "Apparent Superluminal Velocity of Galaxies". Usenet Physics FAQ. University of California, Riverside. Retrieved 2009-11-26.

- ^ Harrison, ER (2003). Masks of the Universe. Cambridge University Press. p. 206. ISBN 0521773512.

- ^ Panofsky, WKH; Phillips, M (1962). Classical Electricity and Magnetism. Addison-Wesley. p. 182. ISBN 9780201057027.

- ^ Schaefer, BE (1999). "Severe limits on variations of the speed of light with frequency". Physical Review Letters. 82: 4964–6. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.4964. arXiv:astro-ph/9810479.

- ^ Ellis, J; Mavromatos, NE; Nanopoulos, DV; Sakharov, AS (2003). "Quantum-Gravity Analysis of Gamma-Ray Bursts using Wavelets". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 403: 409–24. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20030263. arXiv:astro-ph/0210124.

- ^ Füllekrug, M (2004). "Probing the Speed of Light with Radio Waves at Extremely Low Frequencies". Physical Review Letters. 93: 043901. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.043901.

- ^ a b Adelberger, E; Dvali, G; Gruzinov, A (2007). "Photon Mass Bound Destroyed by Vortices". Physical Review Letters. 98: 010402. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.010402. arXiv:hep-ph/0306245.

- ^ Sidharth, BG (2008). The Thermodynamic Universe. World Scientific. p. 134. ISBN 9812812342.

- ^ Amelino-Camelia, G (2009). "Astrophysics: Burst of support for relativity". Nature. 462 (7271): 291–292. doi:10.1038/462291a. PMID 19924200.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - ^ de Podesta, M (2002). Understanding the Properties of Matter. CRC Press. p. 131. ISBN 0415257883.

- ^ "Refractive index of Water, H20 [Liquids]". refractiveindex.info. Mikhail Polyanskiy.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessed=ignored (help) - ^ "Refractive index of Fused Silica [Glasses]". refractiveindex.info. Mikhail Polyanskiy.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessed=ignored (help) - ^

"Refractive index of C [Crystals etc.]". refractiveindex.info. Mikhail Polyanskiy.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessed=ignored (help) - ^ Milonni, PW (2004). Fast light, slow light and left-handed light. CRC Press. p. 25. ISBN 0750309261.

- ^ Toll, JS (1956). "Causality and the Dispersion Relation: Logical Foundations". Physical Review. 104: 1760–1770. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.104.1760.

- ^ Hau, LV; Harris, SE; Dutton, Z; Behroozi, CH (1999). "Light speed reduction to 17 metres per second in an ultracold atomic gas" (PDF). Nature. 397: 594–598. doi:10.1038/17561.

- ^ Liu, C; Dutton, Z; Behroozi, CH; Hau, LV (2001). "Observation of coherent optical information storage in an atomic medium using halted light pulses" (PDF). Nature. 409 (6819): 490–493. doi:10.1038/35054017. PMID 11206540.

- ^ Bajcsy, M; Zibrov, AS; Lukin, MD (2003). "Stationary pulses of light in an atomic medium". Nature. 426 (6967): 638–41. doi:10.1038/nature02176. PMID 14668857.

- ^ Dumé, B (2003). "Switching light on and off". Physics World. Institute of Physics. Retrieved 2008-12-08.

- ^ Whitehouse, D (19 July 2000). "Beam Smashes Light Barrier". BBC News. Retrieved 2008-12-08.

- ^ a b Milonni, PW (2004). "2". Fast light, slow light and left-handed light. CRC Press. ISBN 0750309261.

- ^ Cherenkov, Pavel A. (1934). Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR. 2: 451.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) Reprinted in Selected Papers of Soviet Physicists, Usp. Fiz. Nauk 93 (1967) 385. V sbornike: Pavel Alekseyevich Čerenkov: Chelovek i Otkrytie pod redaktsiej A. N. Gorbunova i E. P. Čerenkovoj, M.,"Nauka, 1999, s. 149-153. (ref) - ^ a b Parhami, B (1999). Introduction to parallel processing: algorithms and architectures. Plenum Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780306459702. and Imbs, D; Raynal, Michel (2009). "Software Transactional Memories: An Approach for Multicore Programming". In Malyshkin, V (ed.). Parallel Computing Technologies. 10th International Conference, PaCT 2009, Novosibirsk, Russia, August 31-September 4, 2009. Springer. p. 26. ISBN 9783642032745.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ A typical value for the refractive index of optical fibre is between 1.518 and 1.538: Midwinter, JE (1991). Optical Fibers for Transmission (2nd ed.). Krieger Publishing Company. ISBN 0894645951.

- ^ "Theoretical vs real-world speed limit of Ping". Royal Pingdom. Pingdom. June 2007. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ "Day 4: Lunar Orbits 7, 8 and 9". The Apollo 8 Flight Journal. NASA. Retrieved 2010-12-16.

- ^ Dickey, JO (1994). "Lunar Laser Ranging: A Continuing Legacy of the Apollo Program". Science. 265 (5171): 482–490. Bibcode:1994Sci...265..482D. doi:10.1126/science.265.5171.482.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Standish, EM (1982). "The JPL planetary ephemerides". Celestial Mechanics. 26: 181–186. Bibcode:1982CeMec..26..181S. doi:10.1007/BF01230883.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Berner, JB; Bryant, SH; Kinman, PW (2007). "Range Measurement as Practiced in the Deep Space Network". Proceedings of the IEEE. 95 (11): 2202–2214. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2007.905128.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Hubble Reaches the "Undiscovered Country" of Primeval Galaxies" (Press release). Space Telescope Science Institute. 5 January 2010.

- ^ "The Hubble Ultra Deep Field Lithograph" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 2010-02-04.

- ^ "The IAU and astronomical units". International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ Further discussion can be found at "StarChild Question of the Month for March 2000". StarChild. NASA. 2000. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ^ a b c "Resolution 1 of the 17th CGPM". BIPM. 1983. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), p. 126, ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-06-04, retrieved 2021-12-16.

- ^ John D. Anderson and Michael Martin Nieto (2009). "Astrometric solar-system anomalies". Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 5. Cambridge University Press: 189–197. doi:10.1017/S1743921309990378. arXiv:0907.2469.

- ^ a b Cohen, IB (1940). "Roemer and the first determination of the velocity of light (1676)". Isis. 31 (2): 327–79. doi:10.1086/347594.

- ^ a b c

"Touchant le mouvement de la lumiere trouvé par M. Rŏmer de l'Académie Royale des Sciences" (PDF). Journal des sçavans (in French): 233–36. 1676.

Translated in "On the Motion of Light by M. Romer". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 12 (136): 893–95. 1677. doi:10.1098/rstl.1677.0024. (As reproduced in Hutton, C; Shaw, G; Pearson, R eds. (1809). "On the Motion of Light by M. Romer". The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, from Their Commencement in 1665, in the Year 1800: Abridged. Vol. 2. London: C. & R. Baldwin. pp. 397–98.{{cite book}}:|first3=has generic name (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help))

The account published in Journal des sçavans was based on a report that Rømer read to the French Academy of Sciences in November 1676 (Cohen, 1940, p. 346). - ^ a b c d Bradley, J (1729). "Account of a new discoved Motion of the Fix'd Stars". Philosophical Transactions. 35: 637–660.

- ^ Duffett-Smith, P (1988). Practical astronomy with your calculator. Cambridge University Press. p. 62. ISBN 0521356997.

- ^ Pitjeva, EV; Standish, EM (2009). "Proposals for the masses of the three largest asteroids, the Moon-Earth mass ratio and the Astronomical Unit". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 103 (4): 365–372. doi:10.1007/s10569-009-9203-8.

- ^ a b IAU Working Group on Numerical Standards for Fundamental Astronomy. "IAU WG on NSFA Current Best Estimates". US Naval Observatory. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- ^ "NPL's Beginner's Guide to Length". UK National Physical Laboratory. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

- ^ a b c d e Gibbs, P (1997). "How is the speed of light measured?". Usenet Physics FAQ. University of California, Riverside. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

- ^ Fowler, M. "The Speed of Light". University of Virginia. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ^ Cooke, J; Martin, M; McCartney, H; Wilf, B (1968). "Direct determination of the speed of light as a general physics laboratory experiment". American Journal of Physics. 36 (9): 847. doi:10.1119/1.1975166.

- ^ Aoki, K; Mitsui, T (2008). "A small tabletop experiment for a direct measurement of the speed of light". American Journal of Physics. 76 (9): 812–815. doi:10.1119/1.2919743. arXiv:0705.3996.

- ^ James, MB; Ormond, RB; Stasch, AJ (1999). "Speed of light measurement for the myriad". American Journal of Physics. 67 (8): 681–714. doi:10.1119/1.19352.

- ^ a b c d e Essen, L; Gordon-Smith, AC (1948). "The Velocity of Propagation of Electromagnetic Waves Derived from the Resonant Frequencies of a Cylindrical Cavity Resonator". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A. 194 (1038): 348–361. Bibcode:1948RSPSA.194..348E. doi:10.1098/rspa.1948.0085. JSTOR 98293.

- ^ a b Rosa, EB; Dorsey, NE (1907). "The Ratio of the Electromagnetic and Electrostatic Units". Bulletin of the Bureau of Standards. 3: 433. doi:10.1103/PhysRevSeriesI.22.367.

- ^ Essen, L (1947). "Velocity of Electromagnetic Waves". Nature. 159 (4044): 611–612. Bibcode:1947Natur.159..611E. doi:10.1038/159611a0.

- ^ a b Essen, L (1950). "The Velocity of Propagation of Electromagnetic Waves Derived from the Resonant Frequencies of a Cylindrical Cavity Resonator". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A. 204 (1077): 260–277. Bibcode:1950RSPSA.204..260E. doi:10.1098/rspa.1950.0172. JSTOR 98433.

- ^

Stauffer, RH (1997). "Finding the Speed of Light with Marshmallows". The Physics Teacher. 35. American Association of Physics Teachers: 231. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "BBC Look East at the speed of light". BBC Norfolk website. BBC. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

- ^ A detailed discussion of the interferometer and its use for determining the speed of light can be found in Vaughan, JM (1989). The Fabry-Perot interferometer. CRC Press. p. 47, pp. 384–391. ISBN 0852741383.

- ^ a b

Froome, KD (1958). "A New Determination of the Free-Space Velocity of Electromagnetic Waves". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences,. 247 (1248). The Royal Society: 109–122. doi:10.1098/rspa.1958.0172. JSTOR 100591.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b Sullivan, DB (2001). "Speed of Light from Direct Frequency and Wavelength Measurements". In Lide, DR (ed.). A Century of Excellence in Measurements, Standards, and Technology (PDF). CRC Press. pp. 191–193. ISBN 0849312477.

- ^ a b c

Evenson, KM (1972). "Speed of Light from Direct Frequency and Wavelength Measurements of the Methane-Stabilized Laser". Physical Review Letters. 29: 1346–49. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.29.1346.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Huygens, C (1690). Traitée de la Lumière (in French). Pierre van der Aa. pp. 8–9.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1086/143021, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1086/143021instead. - ^ Sarton, G (1993). Ancient science through the golden age of Greece. Courier Dover. p. 248. ISBN 0486274950.

- ^ a b c MacKay, RH; Oldford, RW (2000). "Scientific Method, Statistical Method and the Speed of Light". Statistical Science. 15 (3): 254–78. doi:10.1214/ss/1009212817.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1177/107385849900500108, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1177/107385849900500108instead. - ^ Hamarneh, S (1972). "Review: Hakim Mohammed Said, Ibn al-Haitham". Isis. 63 (1): 119. doi:10.1086/350861.

- ^ a b Lester, PM (2005). Visual Communication: Images With Messages. Thomson Wadsworth. pp. 10–11. ISBN 0534637205.

- ^ O'Connor, JJ; Robertson, EF. "Abu Ali al-Hasan ibn al-Haytham". MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. University of St Andrews. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

- ^

Lauginie, P (2005). "Measuring: Why? How? What?" (PDF). Proceedings of the 8th International History, Philosophy, Sociology & Science Teaching Conference. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ O'Connor, JJ; Robertson, EF. "Abu Arrayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni". MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. University of St Andrews. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

- ^ Lindberg, DC (1996). Roger Bacon and the origins of Perspectiva in the Middle Ages: a critical edition and English translation of Bacon's Perspectiva, with introduction and notes. Oxford University Press. p. 143. ISBN 0198239920.

- ^ Lindberg, DC (1974). "Late Thirteenth-Century Synthesis in Optics". In Edward Grant (ed.). A source book in medieval science. Harvard University Press. p. 396. ISBN 9780674823600.

- ^ Marshall, P (1981). "Nicole Oresme on the Nature, Reflection, and Speed of Light". Isis. 72 (3): 357–74 [367–74]. doi:10.1086/352787.

- ^ Boyer, CB (1941). "Early Estimates of the Velocity of Light". Isis. 33 (1): 24. doi:10.1086/358523.

- ^ Galilei, G (1954) [1638]. Dialogues Concerning Two New Sciences. Crew, H; de Salvio A (trans.). Dover Publications. p. 43. ISBN 0486-60099-8.

- ^ Newton, I (1704). "Prop. XI". Optiks. The text of Prop. XI is identical between the first (1704) and second (1719) editions.

- ^ Graneau, P; Assis, AKT (1994). "Kirchhoff on the motion of electricity in conductors" (PDF). Apeiron. 19: 19–25. Retrieved 2010-10-21.

- ^ Giordano, Nicholas J. (2009). College physics: reasoning and relationships. Cengage Learning. p. 787. ISBN 0-534-42471-6., Extract of page 787

- ^ Bergmann, Peter Gabriel (1992). The riddle of gravitation. Courier Dover Publications. p. 17. ISBN 0-486-27378-4., Extract of page 17

- ^ Bais, Sander (2005). The equations: icons of knowledge. Harvard University Press. p. 40. ISBN 0-674-01967-9., Extract of page 40

- ^ O'Connor, JJ; Robertson, EF (November 1997). "James Clerk Maxwell". School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ Michelson, AA; Morley, EW (1887). . American Journal of Science. 34: 333–345.

- ^ French, AP (1983). Special relativity. Van Nostrand Reinhold. pp. 51–57. ISBN 0-442-30782-9.

- ^ French, AP (2009). Special relativity. M I T. pp. 63–64, 267. ISBN 0-7487-6422-4.

- ^ French, AP (1983). Special relativity. Van Nostrand Reinhold. pp. 3–4. ISBN 0-442-30782-9.

- ^ "Resolution 6 of the 15th CGPM". BIPM. 1967. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1063/1.1654608, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1063/1.1654608instead. - ^ "Resolution 2 of the 15th CGPM". BIPM. 1975. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ Tom Wilkie (October 27, 1983). "Time to remeasure the metre". New Scientist. 100 (1381). Reed Business Information: 258 ff. ISSN 0262-4079.

- ^ Taylor, EF; Wheeler, JA (1992). Spacetime Physics: Introduction to Special Relativity (2nd ed.). Macmillan. ISBN 0716723271.

- ^ Penzes, WB (2009). "Time Line for the Definition of the Meter". NIST. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- ^

Adams, S (1997). Relativity: An Introduction to Space-Time Physics. CRC Press. p. 140. ISBN 0748406212.

One peculiar consequence of this system of definitions is that any future refinement in our ability to measure c will not change the speed of light (which is a defined number), but will change the length of the meter!

- ^

Rindler, W (2006). Relativity: Special, General, and Cosmological (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 41. ISBN 0198567316.

Note that [...] improvements in experimental accuracy will modify the meter relative to atomic wavelengths, but not the value of the speed of light!

Further reading

Historical references

- Rømer, O (1676). "Démonstration touchant le mouvement de la lumière trouvé par M. Römer de l'Academie Royale des Sciences". Journal des sçavans (in French): 223–36. Archived from the original on 2007-07-29.

- Translated as "A Demonstration concerning the Motion of Light". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (136): 893–4. 1677. Archived from the original on 2007-07-29.

- Halley, E (1694). "Monsieur Cassini, his New and Exact Tables for the Eclipses of the First Satellite of Jupiter, reduced to the Julian Stile and Meridian of London". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 18 (214): 237–56. doi:10.1098/rstl.1694.0048.

- Fizeau, HL (1849). "Sur une expérience relative à la vitesse de propagation de la lumière" (PDF). Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences (in French). 29: 90–92, 132.

- Foucault, JL (1862). "Détermination expérimentale de la vitesse de la lumière: parallaxe du Soleil". Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences (in French). 55: 501–503, 792–796.

- Michelson, AA (1878). "Experimental Determination of the Velocity of Light". Proceedings of the American Association of Advanced Science. 27: 71–77.

- Michelson, AA; Pease, FG; Pearson, F (1935). "Measurement of the Velocity of Light in a Partial Vacuum". Astrophysical Journal. 82: 26–61. doi:10.1086/143655.

- Newcomb, S (1886). "The Velocity of Light". Nature. 34: 29–32. doi:10.1038/034029c0.

- Perrotin, J (1900). "Sur la vitesse de la lumière". Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences (in French). 131: 731–4.

Modern references

- Brillouin, L (1960). Wave propagation and group velocity. Academic Press.

- Jackson, JD (1975). Classical Electrodynamics (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-30932-X.

- Keiser, G (2000). Optical Fiber Communications (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 32. ISBN 0072321016.

- Ng, YJ (2004). "Quantum Foam and Quantum Gravity Phenomenology". In Amelino-Camelia, G; Kowalski-Glikman, J (ed.). Planck Scale Effects in Astrophysics and Cosmology. Springer. pp. 321ff. ISBN 3540252630.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Helmcke, J; Riehle, F (2001). "Physics behind the definition of the meter". In Quinn, TJ; Leschiutta, S; Tavella, P (ed.). Recent advances in metrology and fundamental constants. IOS Press. p. 453. ISBN 1586031678.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Duff, MJ (2004). "Comment on time-variation of fundamental constants". arXiv:hep-th/0208093.

{{cite arXiv}}:|class=ignored (help)

External links

- Speed of light in vacuum (National Institute of Standards and Technology, NIST)

- Definition of the metre (International Bureau of Weights and Measures, BIPM)

- Data Gallery: Michelson Speed of Light (Univariate Location Estimation) (download data gathered by A.A. Michelson)

- Subluminal (Java applet demonstrating group velocity information limits)

- De Mora Luminis at MathPages

- Light discussion on adding velocities

- Speed of Light (University of Colorado Department of Physics)

- Usenet Physics FAQ

- The Fizeau "Rapidly Rotating Toothed Wheel" Method