Encephalitis

| Encephalitis | |

|---|---|

| |

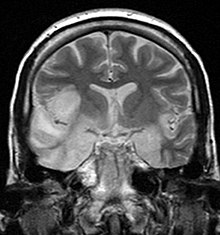

| MRI scan image shows high signal in the temporal lobes and right inferior frontal gyrus in someone with herpes simplex encephalitis. | |

| Specialty | Neurology, infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Headache, fever, confusion, stiff neck, vomiting[1] |

| Complications | Seizures, trouble speaking, memory problems, problems hearing[1] |

| Duration | Weeks to months for recovery[1] |

| Types | Herpes simplex, West Nile, rabies, Eastern equine, others[2] |

| Causes | Infection, autoimmune, certain medication, unknown[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, supported by blood tests, medical imaging, analysis of cerebrospinal fluid[2] |

| Treatment | Antiviral medication, anticonvulsants, corticosteroids, artificial respiration[1] |

| Prognosis | Variable[1] |

| Frequency | 4.3 million (2015)[3] |

| Deaths | 150,000 (2015)[4] |

Encephalitis is inflammation of the brain.[5] The severity can be variable with symptoms including reduction or alteration in consciousness, headache, fever, confusion, a stiff neck, and vomiting.[1][6] Complications may include seizures, hallucinations, trouble speaking, memory problems, and problems with hearing.[1]

Causes of encephalitis include viruses such as herpes simplex virus and rabies virus as well as bacteria, fungi, or parasites.[1][2] Other causes include autoimmune diseases and certain medications.[2] In many cases the cause remains unknown.[2] Risk factors include a weak immune system.[2] Diagnosis is typically based on symptoms and supported by blood tests, medical imaging, and analysis of cerebrospinal fluid.[2]

Certain types are preventable with vaccines.[5] Treatment may include antiviral medications (such as acyclovir), anticonvulsants, and corticosteroids.[1] Treatment generally takes place in hospital.[1] Some people require artificial respiration.[1] Once the immediate problem is under control, rehabilitation may be required.[2] In 2015, encephalitis was estimated to have affected 4.3 million people and resulted in 150,000 deaths worldwide.[3][4]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Adults with encephalitis present with acute onset of fever, headache, confusion, and sometimes seizures. Younger children or infants may present with irritability, poor appetite and fever.[7] Neurological examinations usually reveal a drowsy or confused person. Stiff neck, due to the irritation of the meninges covering the brain, indicates that the patient has either meningitis or meningoencephalitis.[8]

Limbic encephalitis

[edit]Limbic encephalitis refers to inflammatory disease confined to the limbic system of the brain. The clinical presentation often includes disorientation, disinhibition, memory loss, seizures, and behavioral anomalies. MRI imaging reveals T2 hyperintensity in the structures of the medial temporal lobes, and in some cases, other limbic structures. Some cases of limbic encephalitis are of autoimmune origin.[9]

Encephalitis lethargica

[edit]Encephalitis lethargica is identified by high fever, headache, delayed physical response, and lethargy. Individuals can exhibit upper body weakness, muscular pains, and tremors, though the cause of encephalitis lethargica is not currently known. From 1917 to 1928, an epidemic of encephalitis lethargica occurred worldwide.[10]

Cause

[edit]

In 30%-40% of encephalitis cases, the etiology remains unknown.[11]

Viral

[edit]Viral infections are the usual cause of infectious encephalitis.[11] Viral encephalitis can occur either as a direct effect of an acute infection, or as one of the sequelae of a latent infection. The majority of viral cases of encephalitis have an unknown cause; however, the most common identifiable cause of viral encephalitis is from herpes simplex infection.[12] Other causes of acute viral encephalitis are rabies virus, poliovirus, and measles virus.[13]

Additional possible viral causes are arboviral flavivirus (St. Louis encephalitis, West Nile virus), bunyavirus (La Crosse strain), arenavirus (lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus), reovirus (Colorado tick virus), and henipavirus infections.[14][15] The Powassan virus is a rare cause of encephalitis.[16]

Bacterial

[edit]It can be caused by a bacterial infection, such as bacterial meningitis,[17] or may be a complication of a current infectious disease such as syphilis (secondary encephalitis).[18]

Other bacterial pathogens, like Mycoplasma and those causing rickettsial disease, cause inflammation of the meninges and consequently encephalitis. Lyme disease or Bartonella henselae may also cause encephalitis.[citation needed]

Other Infectious Causes

[edit]Certain parasitic or protozoal infestations, such as toxoplasmosis and malaria can also cause encephalitis in people with compromised immune systems.

The rare but typically deadly forms of encephalitis, primary amoebic meningoencephalitis and Granulomatous amoebic encephalitis, are caused by free-living amoeba.[19]

Autoimmune encephalitis

[edit]Autoimmune encephalitis signs can include catatonia, psychosis, abnormal movements, and autonomic dysregulation. Antibody-mediated anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate-receptor encephalitis and Rasmussen encephalitis are examples of autoimmune encephalitis.[20]

Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis is the most common autoimmune form, and is accompanied by ovarian teratoma in 58 percent of affected women 18–45 years of age.[21]

Another autoimmune cause includes acute disseminated encephalitis, a demyelinating disease which primarily affects children.[22]

Diagnosis

[edit]

People should only be diagnosed with encephalitis if they have a decreased or altered level of consciousness, lethargy, or personality change for at least twenty-four hours without any other explainable cause.[23] Diagnosing encephalitis is done via a variety of tests:[24][25]

- Brain scan, done by MRI, can determine inflammation and differentiate from other possible causes.

- EEG, in monitoring brain activity, encephalitis will produce abnormal signal.

- Lumbar puncture (spinal tap), this helps determine via a test using the cerebral-spinal fluid, obtained from the lumbar region.

- Blood test

- Urine analysis

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of the cerebrospinal fluid, to detect the presence of viral DNA which is a sign of viral encephalitis.

Prevention

[edit]Vaccination is available against tick-borne[26] and Japanese encephalitis[27] and should be considered for at-risk individuals. Post-infectious encephalomyelitis complicating smallpox vaccination is avoidable, for all intents and purposes, as smallpox is nearly eradicated.[28] Contraindication to Pertussis immunization should be observed in patients with encephalitis.[29]

Treatment

[edit]An ideal drug to treat brain infection should be small, moderately lipophilic at pH of 7.4, low level of plasma protein binding, volume of distribution of litre per kg, does not have strong affinity towards binding with P-glycoprotein, or other efflux pumps on the surface of blood–brain barrier. Some drugs such as isoniazid, pyrazinamide, linezolid, metronidazole, fluconazole, and some fluoroquinolones have good penetration to blood brain barrier.[30]Treatment (which is based on supportive care) is as follows:[31]

- Antiviral medications (if virus is cause)

- Antibiotics, (if bacteria is cause)

- Steroids are used to reduce brain swelling

- Sedatives for restlessness

- Acetaminophen for fever

- Occupational and physical therapy (if brain is affected post-infection)

Pyrimethamine-based maintenance therapy is often used to treat toxoplasmic encephalitis (TE), which is caused by Toxoplasma gondii and can be life-threatening for people with weak immune systems.[32] The use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), in conjunction with the established pyrimethamine-based maintenance therapy, decreases the chance of relapse in patients with HIV and TE from approximately 18% to 11%.[32] This is a significant difference as relapse may impact the severity and prognosis of disease and result in an increase in healthcare expenditure.[32]

The effectiveness of intravenous immunoglobulin for the management of childhood encephalitis is unclear. Systematic reviews have been unable to draw firm conclusions because of a lack of randomised double-blind studies with sufficient numbers of patients and sufficient follow-up.[33] There is the possibility of a benefit of intravenous immunoglobulin for some forms of childhood encephalitis on some indicators such as length of hospital stay, time to stop spasms, time to regain consciousness, and time to resolution of neuropathic symptoms and fever.[33] Intravenous immunoglobulin for Japanese encephalitis appeared to have no benefit when compared with placebo (pretend) treatment.[33]

Prognosis

[edit]Identification of poor prognostic factors include cerebral edema, status epilepticus, and thrombocytopenia.[34] In contrast, a normal encephalogram at the early stages of diagnosis is associated with high rates of survival.[34]

Epidemiology

[edit]

The number of new cases a year of acute encephalitis in Western countries is 7.4 cases per 100,000 people per year. In tropical countries, the incidence is 6.34 per 100,000 people per year.[35] The number of cases of encephalitis has not changed much over time, with about 250,000 cases a year from 2005 to 2015 in the US. Approximately seven per 100,000 people were hospitalized for encephalitis in the US during this time.[34] In 2015, encephalitis was estimated to have affected 4.3 million people and resulted in 150,000 deaths worldwide.[4][3] Herpes simplex encephalitis has an incidence of 2–4 per million of the population per year.[36]

Terminology

[edit]Encephalitis with meningitis is known as meningoencephalitis, while encephalitis with involvement of the spinal cord is known as encephalomyelitis.[2]

The word is from Ancient Greek ἐγκέφαλος, enképhalos 'brain',[37] composed of ἐν, en, 'in' and κεφαλή, kephalé, 'head', and the medical suffix -itis 'inflammation'.[38]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Meningitis and Encephalitis Information Page". NINDS. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Meningitis and Encephalitis Fact Sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ a b c Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, et al. (GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ a b c Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ a b "Encephalitis". NHS Choices. 2016. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ Ellul M, Solomon T (March 2018). "Acute encephalitis - diagnosis and management". Clinical Medicine. 18 (2): 155–159. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.18-2-155. PMC 6303463. PMID 29626021.

- ^ "Symptoms of encephalitis". NHS. Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Shmaefsky B, Babcock H (2010-01-01). Meningitis. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-3216-7. Archived from the original on 2015-10-30.

- ^ Larner AJ (2013-05-02). Neuropsychological Neurology: The Neurocognitive Impairments of Neurological Disorders. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-60760-6. Archived from the original on 2015-10-30.

- ^ Encephalitis Lethargica at NINDS

- ^ a b "Encephalitis". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 2021-08-08. Retrieved 2024-01-09.

- ^ Roos KL, Tyler KL (2015). "Meningitis, Encephalitis, Brain Abscess, and Empyema". Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (19 ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-180215-4. Archived from the original on 2017-11-17. Retrieved 2017-11-17.

- ^ Fisher DL, Defres S, Solomon T (March 2015). "Measles-induced encephalitis". QJM. 108 (3): 177–182. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcu113. PMID 24865261.

- ^ Kennedy PG (March 2004). "Viral encephalitis: causes, differential diagnosis, and management". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 75 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1): i10–15. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2003.034280. PMC 1765650. PMID 14978145.

- ^ Broder CC, Geisbert TW, Xu K, Nikolov DB, Wang LF, Middleton D, et al. (2012). "Immunization strategies against henipaviruses". Henipavirus. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 359. pp. 197–223. doi:10.1007/82_2012_213. ISBN 978-3-642-29818-9. PMC 4465348. PMID 22481140.

- ^ "Symptoms & Treatment | Powassan | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 4 December 2018. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ^ Ashar BH, Miller RG, Sisson SD (2012-01-01). Johns Hopkins Internal Medicine Board Review: Certification and Recertification. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-1-4557-0692-1. Archived from the original on 2015-11-29.

- ^ Hama K, Ishiguchi H, Tuji T, Miwa H, Kondo T (2008-01-01). "Neurosyphilis with mesiotemporal magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities". Internal Medicine. 47 (20): 1813–1817. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.47.0983. PMID 18854635.

- ^ "Free Living Amebic Infections". 2024-06-24.

- ^ Armangue T, Petit-Pedrol M, Dalmau J (November 2012). "Autoimmune encephalitis in children". Journal of Child Neurology. 27 (11): 1460–1469. doi:10.1177/0883073812448838. PMC 3705178. PMID 22935553.

- ^ Dalmau J, Graus F (March 2018). "Antibody-Mediated Encephalitis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 378 (9): 840–851. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1708712. hdl:2445/147222. PMID 29490181. S2CID 3623281.

- ^ Encephalitis at eMedicine

- ^ Venkatesan A, Tunkel AR, Bloch KC, Lauring AS, Sejvar J, Bitnun A, et al. (October 2013). "Case definitions, diagnostic algorithms, and priorities in encephalitis: consensus statement of the international encephalitis consortium". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 57 (8): 1114–1128. doi:10.1093/cid/cit458. PMC 3783060. PMID 23861361.

- ^ "Encephalitis: Diagnosis". NHS Choices. Archived from the original on 2015-07-16. Retrieved 2015-08-05.

- ^ Kneen R, Michael BD, Menson E, Mehta B, Easton A, Hemingway C, et al. (May 2012). "Management of suspected viral encephalitis in children - Association of British Neurologists and British Paediatric Allergy, Immunology and Infection Group national guidelines". The Journal of Infection. 64 (5): 449–477. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2011.11.013. PMID 22120594.

- ^ "Tick-borne Encephalitis: Vaccine". International travel and health. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ^ "Japanese encephalitis". Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ^ "CDC Media Statement on Newly Discovered Smallpox Specimens". www.cdc.gov. January 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-05-20. Retrieved 2016-05-19.

- ^ "Contraindications and Precautions to Commonly Used Vaccines in Adults". Vaccines. Center for Disease Control. Archived from the original on 2015-08-23. Retrieved 2015-08-05.

- ^ Nau R, Sörgel F, Eiffert H (October 2010). "Penetration of drugs through the blood-cerebrospinal fluid/blood-brain barrier for treatment of central nervous system infections". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 23 (4): 858–883. doi:10.1128/CMR.00007-10. PMC 2952976. PMID 20930076.

- ^ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Encephalitis

- ^ a b c Connolly MP, Goodwin E, Schey C, Zummo J (February 2017). "Toxoplasmic encephalitis relapse rates with pyrimethamine-based therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis". Pathogens and Global Health. 111 (1): 31–44. doi:10.1080/20477724.2016.1273597. PMC 5375610. PMID 28090819.

- ^ a b c Iro MA, Martin NG, Absoud M, Pollard AJ (October 2017). "Intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of childhood encephalitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (10): CD011367. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011367.pub2. PMC 6485509. PMID 28967695.

- ^ a b c Venkatesan A (June 2015). "Epidemiology and outcomes of acute encephalitis". Current Opinion in Neurology. 28 (3): 277–282. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000199. PMID 25887770. S2CID 21041693.

- ^ Jmor F, Emsley HC, Fischer M, Solomon T, Lewthwaite P (October 2008). "The incidence of acute encephalitis syndrome in Western industrialised and tropical countries". Virology Journal. 5 (134): 134. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-5-134. PMC 2583971. PMID 18973679.

- ^ Rozenberg F, Deback C, Agut H (June 2011). "Herpes simplex encephalitis : from virus to therapy". Infectious Disorders Drug Targets. 11 (3): 235–250. doi:10.2174/187152611795768088. PMID 21488834.

- ^ "Woodhouse's English-Greek Dictionary" (in German). The University of Chicago Library. Archived from the original on 2017-03-05. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- ^ The word seems to have had a meaning of "lithic imitation of the human brain" at first, according to the Trésor de la langue française informatisé (cf. the article on "encéphalite" Archived 2017-11-05 at the Wayback Machine). The first use in the medical sense is attested from the early 19th century in French (J. Capuron, Nouveau dictionnaire de médecine, chirurgie..., 1806), and from 1843 in English respectively (cf. the article "encephalitis" in the Online Etymology Dictionary). Retrieved 11 March 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Steiner I, Budka H, Chaudhuri A, Koskiniemi M, Sainio K, Salonen O, et al. (May 2005). "Viral encephalitis: a review of diagnostic methods and guidelines for management". European Journal of Neurology. 12 (5): 331–343. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01126.x. PMID 15804262. S2CID 8986902.

- Basavaraju SV, Kuehnert MJ, Zaki SR, Sejvar JJ (September 2014). "Encephalitis caused by pathogens transmitted through organ transplants, United States, 2002-2013". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 20 (9): 1443–1451. doi:10.3201/eid2009.131332. PMC 4178385. PMID 25148201.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. "Encephalitis". PubMed Health. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2015-08-05.