Terrestrial planet

A terrestrial planet, telluric planet or rocky planet is a planet that is primarily composed of silicate rocks and/or metals. Within the solar system, the terrestrial planets are the inner planets closest to the Sun. The terms are derived from Latin words for Earth (Terra and Tellus), so these planets are, in a certain way, "Earth-like".

Terrestrial planets are substantially different from gas giants, which might not have solid surfaces and are composed mostly of some combination of hydrogen, helium, and water existing in various physical states.

Structure

Terrestrial planets all have roughly the same structure: a central metallic core, mostly iron, with a surrounding silicate mantle. The Moon is similar, but has a much smaller iron core. Terrestrial planets have canyons, craters, mountains, and volcanoes. Terrestrial planets possess secondary atmospheres — atmospheres generated through internal volcanism or comet impacts, as opposed to the gas giants, which possess primary atmospheres — atmospheres captured directly from the original solar nebula.[1]

Theoretically, there are two types of terrestrial or rocky planets, one dominated by silicon compounds and another dominated by carbon compounds, like carbonaceous chondrite asteroids. These are the silicate planets and carbon planets (or "diamond planets") respectively.

Solar terrestrial planets

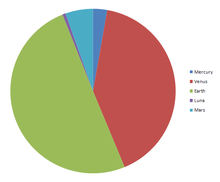

Earth's solar system has four terrestrial planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. Only one terrestrial planet, Earth, is known to have an active hydrosphere.

During the formation of the solar system, there were probably many more (planetesimals), but they have all merged with or been destroyed by the four remaining worlds in the solar nebula.

Plutoids, objects like Pluto, are similar to terrestrial planets in the fact that they do have a solid surface, but are composed of more icy materials.

Density trends

The uncompressed density of a terrestrial planet is the average density its materials would have at zero pressure. A higher uncompressed density indicates higher metal content. Uncompressed density is used rather than true average density because compression within planet cores increases their density (making average density depend on planet size as well as composition).

The uncompressed densities of the solar terrestrial planets and the three largest asteroids are shown below. Densities generally trends towards lower values as the distance from the sun increases.

| Object | mean density | uncompressed density | semi-major axis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury |

5.4 g cm−3 | 5.3 g cm−3 | 0.39 AU |

| Venus |

5.2 g cm−3 | 4.4 g cm−3 | 0.72 AU |

| Earth |

5.5 g cm−3 | 4.4 g cm−3 | 1.0 AU |

| Moon |

3.3 g cm−3 | 3.3 g cm−3 | 1.0 AU |

| Mars |

3.9 g cm−3 | 3.8 g cm−3 | 1.5 AU |

| Vesta |

3.4 g cm−3 | 3.4 g cm−3 | 2.3 AU |

| Pallas |

2.8 g cm−3 | 2.8 g cm−3 | 2.8 AU |

| Ceres |

2.1 g cm−3 | 2.1 g cm−3 | 2.8 AU |

The main exception to this rule is the density of the Moon, which probably owes its lower density to its unusual origin.

It is unknown whether extrasolar terrestrial planets in general will also follow this trend. E.g. Kepler-10b does: it has a density of 8.8 g cm−3, and orbits its star much closer than Mercury. On the other hand, the planets Kepler-11 b to f also orbit closer than Mercury, but have lower densities than the Sun's planets.[2]

Extrasolar terrestrial planets

The majority of planets found outside our solar system have been gas giants since they produce more pronounced wobbles in the host stars and are thus more easily detectable. However, a number of extrasolar planets are suspected to be terrestrial.

In the early 1990s, the first extrasolar planets were discovered orbiting the pulsar PSR B1257+12 with masses of 0.02, 4.3, and 3.9 times that of Earth's. They were discovered by accident: their transit caused interruptions in the pulsar's radio emissions (had they not been orbiting around a pulsar, they would not have been found).

When 51 Pegasi b, the first and only extrasolar planet found up until then around a star still undergoing fusion, was discovered, many astronomers assumed it must be a gigantic terrestrial, as it was assumed no gas giant could exist as close to its star (0.052 AU) as 51 Pegasi b did. However, subsequent diameter measurements of a similar extrasolar planet (HD 209458 b), which transited its star showed that these objects were indeed gas giants.

In June 2005, the first planet around a fusing star that may be terrestrial was found orbiting around the red dwarf star Gliese 876, 15 light years away. That planet has a mass of 7 to 9 times that of earth and an orbital period of just two Earth days. But the radius and composition of Gliese 876 d is unknown.

On 10 August 2005, Probing Lensing Anomalies NETwork/Robotic Telescope Network (PLANET/RoboNet) and Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE) observed the signature of a cold planet designated OGLE-2005-BLG-390Lb, about 5.5 times the mass of Earth, orbiting a star about 21,000 light years away in the constellation Scorpius. The newly discovered planet orbits its parent star at a distance similar to that of our solar system's asteroid belt. The planet revealed its existence through a technique known as gravitational microlensing, currently unique in its capability to detect planets with masses down to that of Earth.

In April 2007, a team of 11 European scientists announced the discovery of a planet outside our solar system that is potentially habitable, with Earth-like temperatures. The planet was discovered by the European Southern Observatory's telescope in La Silla, Chile, which has a special instrument that splits light to find wobbles in different wave lengths. Those wobbles can reveal the existence of other worlds. What they revealed is planets circling the red dwarf star, Gliese 581. Gliese 581 c was considered to be habitable at first, but more recent study (April 2009)[3] suggests Gliese 581 d is a better candidate. Regardless, it has fueled interest in looking at planets circling dimmer stars. About 80 percent of the stars near Earth are red dwarfs. The Gliese 581 (c and d) planets are about five to seven times heavier than Earth, classifying them as super-Earths.

Gliese 581 e is only about 1.9 Earth mass,[3] but could have 2 orders of magnitude more tidal heating than Jupiter’s volcanic satellite Io.[4] An ideal terrestrial planet would be 2 Earth masses with a 25 day orbital period around a M dwarf star.[5]

The discovery of Gliese 581 g was announced in September 2010, and is believed to be the first Goldilocks planet ever found, the most Earth-like planet, and the best exoplanet candidate with the potential for harboring life found to date.

The Kepler Mission endeavours to discover Earth-like planets orbiting around other stars by observing their transits across the star. The Kepler spacecraft was launched on 6 March 2009. The duration of the mission will need to be about three and a half years long to detect and confirm an Earth-like planet orbiting at an Earth-like distance from the host star. Since it will take intervals of one year for a truly Earth-like planet to transit (cross in front of its star), it will take about four transits for a reliable reading.

Dimitar Sasselov, the Kepler mission co-investigator, recently mentioned at the 2010 TED Conference that there have been hundreds more candidate terrestrial planets discovered since Kepler went online. If these planets are confirmed via further investigation, then it will represent the largest find of extrasolar planets to date. The Kepler science teams are, for now, keeping the initial results of any candidate planets a secret so they can confirm their results. The first public announcement of any such results is expected in the early part of 2011.[6][7]

On February 2, 2011, the Kepler Space Observatory Mission team released a list of 1235 extrasolar planet candidates, including 54 that may be in the "habitable zone."[8][9] Some of these candidates were "Earth-size" and "super-Earth-size" [defined as "less than or equal to 2 Earth radii (Re)" (or, Rp ≤ 2.0 Re) - Table 5].[8] Six of these candidates [namely: KOI 326.01 (Rp=0.85), KOI 701.03 (Rp=1.73), KOI 268.01 (Rp=1.75), KOI 1026.01 (Rp=1.77), KOI 854.01 (Rp=1.91), KOI 70.03 (Rp=1.96) - Table 6][8] are in the "habitable zone."[8] A more recent study found that one of these candidates (KOI 326.01) is in fact much larger and hotter than first reported.[10]

A number of other telescopes capable of directly imaging extrasolar terrestrial planets are also on the drawing board. These include the Terrestrial Planet Finder, Space Interferometry Mission, Darwin, New Worlds Mission, and Overwhelmingly Large Telescope.

Most Earth-like exoplanets

| Title | Planet | Star | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closest planet to 1 MEarth | Gliese 581 e | Gliese 581 | 1.7 to 3.1 MEarth | close to star and potentially volcanic like Io.[4] |

| Kepler-11f | Kepler-11 | 2.3 MEarth[2] | ||

| Closest planet to 1 Earth Radius | Kepler-10b | Kepler-10 | 1.416 REarth[2] | Has a mass of 3.3-5.7 MEarth. The less-massive Gliese 581 e is therefore probably smaller than Kepler-10b, unless it has a much lower density |

| Highest probability of liquid water | Gliese 581 g (unconfirmed) |

Gliese 581 | not known explicitly | 3.1 MEarth (min mass); in central habitable zone of red dwarf star.[3] |

Types

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2011) |

Several possible classifications for terrestrial planets have been proposed[11]:

- Silicate planet

- The standard type of terrestrial planet seen in the Solar System, made primarily of silicon-based rocky mantle with a metallic (iron) core.

- Iron planet

- A theoretical type of terrestrial planet that consists almost entirely of iron and therefore has a higher density and a smaller radius than other terrestrial planets of comparable mass. Mercury in our Solar System has a metallic core equal to 60-70% of its planetary mass. Iron planets are believed to form in the high-temperature regions close to a star, like Mercury, and if the protoplanetary disk is rich in iron.

- Coreless planet

- A theoretical type of terrestrial planet that consists of silicate rock but has no metallic core, i.e. the opposite of an iron planet. The Solar System contains no coreless planets but chondrite asteroids and meteorites are common. Coreless planets are believed to form farther from the star where volatile oxidizing material is more common.

- Carbon planet or diamond planet

- A theoretical type of terrestrial planet, composed primarily of carbon-based minerals. The Solar System contains no carbon planets, but does have carbonaceous asteroids.

- Super-Earth

- Super-Earths represent the upper-end of the terrestrial planet mass range.

See also

- Earth analog

- Gas giant — also known as Jovian or Giant planets.

- Dwarf planet

- Planetary habitability

References

- ^ Dr. James Schombert (2004). "Primary Atmospheres (Astronomy 121: Lecture 14 Terrestrial Planet Atmospheres)". Department of Physics University of Oregon. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

{{cite web}}: External link in|author= - ^ a b c http://kepler.nasa.gov/Mission/discoveries/

- ^ a b c "Lightest exoplanet yet discovered". ESO (ESO 15/09 - Science Release). 2009-04-21. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ^ a b Barnes, Rory; Jackson, Brian; Greenberg, Richard; Raymond, Sean N. (2009-06-09). "Tidal Limits to Planetary Habitability". arXiv:0906.1785v1 [astro-ph].

{{cite arXiv}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help) - ^ M. Mayor, X. Bonfils, T. Forveille, X. Delfosse, S. Udry, J.-L. Bertaux, H. Beust, F. Bouchy, C. Lovis, F. Pepe, C. Perrier, D. Queloz, N. C. Santos (2009). "The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets,XVIII. An Earth-mass planet in the GJ 581 planetary system". arXiv:0906.2780 [astro-ph].

{{cite arXiv}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://news.discovery.com/space/kepler-scientist-galaxy-is-rich-in-earth-like-planets.html

- ^ http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/80beats/2010/07/26/keplers-early-results-suggest-earth-like-planets-are-dime-a-dozen/

- ^ a b c d Borucki, William J. (1 February

2011). "Characteristics of planetary candidates observed by Kepler, II: Analysis of the first four months of data" (PDF). arXiv. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); line feed character in|date=at position 11 (help) - ^ [http://arxiv.org/abs/1006.2799 Characteristics of Kepler Planetary Candidates Based on the First Data Set: The Majority are Found to be Neptune-Size and Smaller], William J. Borucki, for the Kepler Team (Submitted on 14 Jun 2010)

- ^ Grant, Andrew (8 March 2011`). "Exclusive: "Most Earth-Like" Exoplanet Gets Major Demotion—It Isn't Habitable". 80beats. Discover Magazine. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ http://www.astrobio.net/pressrelease/2476/all-planets-possible

- Astronomers Find First Earth-like Planet in Habitable Zone ESO - European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere, 27 April 2007

- Found: one Earth-like planet Astronomers use gravity lensing to spot homely planets. By Mark Peplow, News @ Nature.com, 25 January 2006.

- Beaulieu J.P., et al. (2006) Nature, 439, 437-440.

- National Science Foundation press release "Closer to Home."

- A New Path to New Earths National Science Foundation webcast.

- Ogling Distant Stars National Science Foundation grant report.

- Wolszczan's Pulsar Planets.

- PLANET Homepage.

- RoboNet Homepage.

- OGLE Homepage.

- MOA Homepage.

External links

- SPACE.com: Q&A: The IAU's Proposed Planet Definition 16 August 2006 2:00 am ET

- BBC News: Q&A New planets proposal Wednesday, 16 August 2006, 13:36 GMT 14:36 UK