University of Dallas

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| |

| Latin: Universitas Dallasensis | |

| Motto | Veritatem, Justitiam Diligite[1] |

|---|---|

Motto in English | Love Ye Truth and Justice[1] |

| Type | Private university[2] |

| Established | 1956[3] |

Religious affiliation | Roman Catholic[2] |

Academic affiliations | ACCU[4] CIC[5] NAICU[6] |

| Endowment | $74.9 million (2020)[7] |

| Chancellor | Edward J. Burns |

| President | Jonathan J. Sanford |

Academic staff | 136 full-time, 102 part-time[8] |

| Undergraduates | 1,342 (2015) [9] |

| Postgraduates | 1,045 (2015) [9] |

| Location | , , United States[2] 32°50′42″N 96°55′33″W / 32.8451074°N 96.925807°W[10] |

| Campus | Urban;[2] 744 acres (301 hectares)[11] |

| Colors | Navy and White[12] |

| Nickname | Crusaders[13] |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division III – SCAC (non-football) |

| Website | www |

The University of Dallas is a private Catholic university in Irving, Texas. Established in 1956, it is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools.[14]

The university comprises four academic units: the Braniff Graduate School of Liberal Arts, the Constantin College of Liberal Arts, the Satish & Yasmin Gupta College of Business, and the School of Ministry.[15] Dallas offers several master's degree programs and a doctoral degree program with three concentrations.[16] As of 2017, there are 136 full-time faculty and 102 part-time faculty.[8]

History

The University of Dallas' charter dates from 1910 when the Western Province of the Congregation of the Mission (Vincentians) renamed Holy Trinity College in Dallas, which they had founded in 1905.[17][18] The provincial of the Western Province closed the university in 1928, and the charter reverted to the Diocese of Dallas. In 1955, the Western Province of the Sisters of Saint Mary of Namur obtained it to create a new higher education institution in Dallas that would subsume their junior college, Our Lady of Victory College, located in Fort Worth.[19] The sisters, together with Eugene Constantin Jr. and Edward R. Maher Sr., petitioned the Diocese of Dallas to sponsor the university, though ownership was entrusted to a self-perpetuating independent board of trustees.[20]

The University character was defined from its first day as being quite unlike the other Catholic universities of Texas and in fact unlike most Catholic colleges nationwide because of the understanding in Bishop Gorman of what a great University was supposed to be. This understanding came in great part from his own education in Europe between the wars at the Louvain, the Catholic University in Belgium often thought to be the greatest Catholic University in the world.[21]

"Bishop Gorman, as chancellor of the new university, announced that it would be a Catholic coeducational institution welcoming students of all faiths and races and offering work on the undergraduate level, with a graduate school to be added as soon as possible. The new University of Dallas opened to ninety-six students in September 1956 on a 1,000-acre tract of rolling hills northwest of Dallas."[20]

The Sisters of Saint Mary of Namur, monks from the Order of Cistercians (Cistercians), friars from the Order of Friars Minor (Franciscans), and several lay professors formed the university's original faculty.[20] The Franciscans departed three years later; however, friars from the Order of Preachers (Dominicans) joined the faculty in 1958 and built St. Albert the Great Priory on campus. The Cistercians established Our Lady of Dallas Abbey in 1958[22] and Cistercian Preparatory School in 1962,[23] which are both adjacent to campus. The School Sisters of Notre Dame arrived in 1962 and opened the Notre Dame Special School for children with learning difficulties in 1963[24] and a motherhouse for the Dallas Province in 1964,[25] which were both on campus. The sisters moved the school to Dallas in 1985 and closed the motherhouse in 1987. The faculty now is almost exclusively lay and includes several distinguished scholars.

A grant from the Blakley-Braniff Foundation established the Braniff Graduate School in 1966 and allowed the construction of the Braniff Graduate Center. The Constantin Foundation similarly endowed the undergraduate college, and, in 1970, the Board of Trustees named the undergraduate college the Constantin College of Liberal Arts. The Graduate School of Management, begun in 1966, offers a large MBA program. Programs in art and English also began in 1966. In 1973, the Institute of Philosophic Studies, the doctoral program of the Braniff Graduate School and an outgrowth of the Kendall Politics and Literature Program, was initiated. The School of Ministry began in 1987. The College of Business, incorporating the Gupta Graduate School of Management and undergraduate business, opened in 2003.

Since the first class in 1960, university graduates have won significant honors, including 39 Fulbright awards.[26] [27]

Accreditation by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools came in 1963 and has been reaffirmed regularly.[14] In 1989, it was the youngest higher education institution to ever be awarded a Phi Beta Kappa chapter.[28]

In 2015 the university applied for an exception to Title IX allowing it to discriminate based on gender identity for religious reasons. The university "cannot encourage individuals to live in conflict with Catholic principles" according to president Thomas Keefe. In 2016 the organization Campus Pride ranked the college among the worst schools in Texas for LGBT students.[29]

The university briefly considered a large expansion into adult education in 2017. That idea proved unpopular with many faculty and was shelved.[30]

President Thomas W. Keefe was hired from Benedictine University to serve as president.[31] Like his predecessors, he quickly ran into controversy as he oversaw efforts to adapt the way the University operates to those associated with more conventional American Catholic colleges and universities.[32][33][34] In 2017, Keefe's leadership was strongly and publicly challenged by over half the faculty and thousands of alumni members of an independent alumni group called UD Alumni for Liberal Education.[35][36][37][34] Their complaint was over a proposal to add a new college within the university that it was believed would have watered down standards.[38] After almost nonstop controversy and multiple efforts by Trustees to rein in the controversies, on Good Friday of 2018, after an extended and unexplained absence from work, the university's trustees voted to fire Keefe as university president effective at the end of the academic year.[39][37]

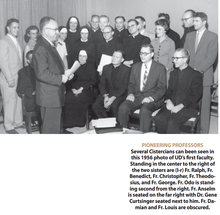

The Role of the Cistercians

Bishop Thomas Gorman wrote as early as 1954 to Fr. Anselm Nagy, O. Cist. to ask the displaced Hungarian Cistercian fathers from the Monastery of Zirc, Hungary to come assist in founding the university. On the first day of classes in September 1956, 9 Cistercian fathers, half the entire faculty, were employed at the new university.[40] The history of UD is connected to both those founding Cistercian priests and the many more Hungarians who would move to Dallas over the next decade and begin teaching at UD.[41]

Guadalupe art print scandal

On February 14, 2008, an image of Our Lady of Guadalupe was removed without permission from the Upper Gallery of the Haggerty Art Village. The image, entitled "Saint or Sinner", was on loan from Murray State University in Kentucky as part of a larger exhibit of works by Murray State University students.[42][43] The piece reportedly portrayed the Virgin Mary as a stripper. Immediate responses to the piece by students when it went on display were largely negative; to appease concerns, signage was put up warning students that "some items [on display] might be considered offensive."[42][43] The university's president, Frank Lazarus, publicly condemned the theft. Reaction to Dr. Lazarus' statement prompted heated campus discussion and faced negative reception from online Catholic and conservative tabloids.[44]

Governance and leadership

As of 2022, the President is Jonathan J. Sanford, an American philosopher who previously served as the school's provost.

The University of Dallas is governed by a board of trustees. According to the university's by-laws, the Bishop of Dallas is an ex-officio voting member.

Edward Burns, Bishop of the Diocese of Dallas, currently serves as the chancellor.[45] The office, held by a Catholic bishop per the constitution of the university, is an unpaid, honorary position.

Previous chancellors include:

- Thomas Kiely Gorman (1954–1969)

- Thomas Ambrose Tschoepe (1969–1990)

- Charles Victor Grahmann (1990–2007)

- Kevin J. Farrell (2008-2016)

Previous presidents include:

- F. Kenneth Brasted (1956–1959)

- Robert J. Morris (1960–1962)

- Donald A. Cowan (1962–1977)

- John R. Sommerfeldt (1978–1980)

- Robert F. Sasseen (1981–1995)[46]

- Milam J. Joseph (1996–2003)

- Frank Lazarus (2004–2010)

- Thomas Keefe (2010-2018)[47]

- Thomas S. Hibbs (2019–2021)

Campus

The university is located in Irving, Texas, on a 744-acre (301 hectare) campus in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex.[11] The Las Colinas development is nearby. It is 10 miles (16 km) from downtown Dallas. The campus consists mostly of mid-century modernist, earth-toned brick buildings set amidst the native Texas landscape. Several of these buildings were designed by the well-known Texas architect O'Neil Ford (dubbed the Godfather of Texas modernism).[48][49] The mall is the center of campus, with the 187.5 feet tall (57.15 meters) Braniff Memorial Tower as its focal point.

Perhaps reflecting prevailing biases against mid-century modern architecture, The Princeton Review once mentioned the University of Dallas as having the fourth-least beautiful campus among the America's top colleges and universities, along with several other campuses with abundant modern architecture.[50] Travel + Leisure's October 2013 issue lists it as one of America's ugliest college campuses, citing its "low-profile, boxy architecture that bears uncanny resemblance to a public car park", but noting that a recent $12 million donation from alumni Satish and Yasmin Gupta would bring new campus construction.[51]

A Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) Orange Line light-rail station opened near campus on July 30, 2012.[52]

The campus is home to the Orpheion Theatre, a small Greek-style playing space built into a hillside. The theatre was constructed in 2003, and has since been used for a handful of mainstage and student productions.

Enrollment

- 1,471 students

- 44% in-state; 55% out-of-state; 1% international

- 98% full-time

- 56% female; 44% male

- 99% age 24 and under

- 78% Catholic[8]

- 27% minority

The 2019–2020 estimated charges, including tuition, room, board, and fees, for full-time undergraduates is $59,600. This is an increase from the 2016–2017 academic year of $54,976.[55]

81% of freshmen who began their degree programs in Fall 2014 returned as sophomores in Fall 2015. 66% of freshmen who began their degree programs in Fall 2009 graduated within 4-years.[56]

Graduate

Academics

Core curriculum and traditional liberal education

The university has resisted a focus on "trades and job training" and pursued the traditional ideas of a liberal education according to the model described by John Henry Newman in The Idea of a University. The university's "Core Curriculum" is a collection of approximately twenty courses (two years) of common study covering philosophy, theology, history, literature, politics, economics, mathematics, science, art, and a foreign language.[57] The curriculum not only includes a slate of required courses, but includes specific standardized texts, which permit professors to assume a common body of knowledge and speak across disciplines.[58] Classes in these core subjects typically have an average class size of 16 students to permit frequent discussion.[57] Dallas is one of 25 schools graded "A" by the American Council of Trustees and Alumni for a solid core curriculum.[59]

There is a similar Core Curriculum for graduate studies in the Braniff Graduate School of Liberal Arts.[60]

Undergraduate

Undergraduate students are enrolled in the Constantin College of Liberal Arts, the Satish & Yasmin Gupta College of Business, or the Ann & Joe O. Neuhoff School of Ministry. The university awards Bachelor of Arts (BA) and Bachelor of Science (BS) degrees.

UD offers a five-year dual degree program in Electrical Engineering, in collaboration with The University of Texas at Arlington.[61]

In 1970, the university started a study abroad program in which Dallas students, generally sophomores, spend a semester at its campus southeast of Rome in the Alban Hills along the Via Appia Nuova.[62] In June 1994, the property was renovated and renamed the Eugene Constantin Rome Campus. It includes a library, a chapel, housing, a dining hall, classrooms, a tennis court, a bocce court, a swimming pool, an outdoor Greco-Roman theater, vineyards, and olive groves.

Graduate programs

The Braniff Graduate School of Liberal Arts administers master's degrees in American studies, art, English, humanities, philosophy, politics, psychology, and theology, as well as an interdisciplinary doctoral program with concentrations in English, philosophy, and politics.

The Satish and Yasmin Gupta College of Business is an AACSB-accredited business school offering a part-time MBA program for working professionals, a Master of Science program, a Doctor of Business Administration (DBA), Graduate Certificates, graduate preparatory programs, and professional development courses.

The Ann & Joe O. Neuhoff School of Ministry offers master's degrees in Theological Studies (MTS), Religious Education (MRE), Catholic School Leadership (MCSL), Catholic School Teaching (MCST), and Pastoral Ministry (MPM). The University of Dallas School of Ministry offers a comprehensive, four-year Catholic Biblical School (CBS) certification program. This program, which covers every book of the Bible, is offered onsite and online in both English and Spanish.

Rankings

| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| Master's | |

| Washington Monthly[63] | 80 |

| Regional | |

| U.S. News & World Report[64] | 12 (West) |

| National | |

| Forbes[65] | 225 |

Undergraduate

- Ranked No. 9 in the nation as the least LGBT friendly by Princeton Review in 2017 and 15th in 2018[66]

- Ranked No. 12 among Western regional universities by U.S. News & World Report (2022 edition).[67]

- Ranked No. 15 among master's universities by The Washington Monthly (2015 edition).[68]

- Ranked No. 64 among Western regional universities on the Webometrics Ranking of World Universities (2012 edition).[69]

- Ranked No. 225 on Forbes list of America's Best Colleges (2019 edition).[70]

- Listed as one of the 126 best colleges in the Western United States by The Princeton Review.[50]

- Earned an A-grade on the 2011 "What Will They Learn?" project of the American Council of Trustees and Alumni.[71]

- Endorsed by the Cardinal Newman Society, a conservative Catholic association. (Twenty schools in the US received such an endorsement).[72][73]

- A 1998 book of conservative college recommendations, Choosing the Right College, strongly endorsed the University of Dallas.[74]

Graduate

- The Department of Art was ranked No. 191 by the U.S. News & World Report's Best Graduate School Rankings 2016.[75]

- The 2010 National Research Council Assessment of Research-Doctorate Programs in the US[76] ranked the University of Dallas' doctoral concentrations at or near the bottom (survey-based quality score) of those surveyed in the US: English: 116-119/119;[77] philosophy: 76-89/90;[78] politics: 100-105/105.[79]

- A 2010 survey of political theory professors published in the journal Political Science & Politics ranked the doctoral concentration in politics 29th out of 106-surveyed programs in the US specializing in political theory.[80]

Research

The on-campus editorial offices of Dallas Medieval Texts and Translations have been publishing a book series of medieval Latin texts with facing English translations. The goal of the series is to build a library that will represent the whole breadth and variety of medieval civilization. The series is open-ended; as of May, 2016, it has published 21 volumes.[81]

Haggerty Art Village

The Braniff Graduate School of Liberal Arts features a small, graduate art program, located in Haggerty Art Village. Haggerty Art Village is separated from the rest of campus by a wooded grove, and the social atmosphere around the village is considerably different from the rest of the university.

Haggerty Art Village itself features printmaking, painting, sculpture, and ceramics facilities, though graduate students are not bound to a single medium, and receive their degree as a broader "art" classification. The program is small, with only 16 graduate art students.[citation needed]

The University's gallery is named after Beatrice Haggerty who helped form the Art Village. Haggerty's involvement with the art program came after her daughter Kathleen was seriously injured in an auto accident. The Haggerty gift of the first art building in 1960 was engineered for her therapy. Haggerty suggested to her husband Patrick E. Haggerty that the new university could benefit by a small building for sculpture. In return, their daughter had access to the needed therapeutic work. Beatrice Haggerty simultaneously cultivated partnerships and future opportunity for the university's art program to flourish. After the completion of the Patrick and Beatrice Haggerty Museum of Art in Wisconsin, Haggerty again donated to fund the building of the first art building at the University of Dallas in 1960. It is currently one of six structures that make up the Haggerty Art Village.

In 1994 a fundraising campaign was launched for the completion of more buildings to change the existing structures into a proper village. The funds would renovate the older art buildings, add a multipurpose art history building, a new sculpture facility, and an art foundations building.[82][83]

Media

The student newspaper is The University News, published weekly on Wednesdays both in-print and online. The yearbook, first published in 1957,[84] is The Crusader. Ramify, the official journal of the Braniff Graduate School of Liberal Arts, has been published since 2009.[85] OnStage Magazine has been operated by the Drama Department since 2016. The Mockingbird, a student-ran and student-funded publication, began monthly printing in September 2020.[86] Since 2011, the Phi Beta Kappa liberal arts honor society has published the University Scholar once a semester to showcase essays, short stories, poems, and scientific abstracts of the university's undergraduates.[87]

The Office of Advancement publishes Tower Magazine for alumni on a twice yearly basis, usually in Summer and in Winter.

Residence life

On campus residency is required of all students who have not yet attained senior status or who are under 21 and are not married, not a veteran of the military, or who do not live with their parents or relatives in the Dallas–Fort Worth area. These requirements change from year to year depending upon the size of the incoming freshman class; for instance, in 2009, all students with senior credit standing were required to live off campus. Freshmen live in traditional single-sex halls, while upperclassmen live either in the University's co-ed dormitory or off-campus.

There are five traditional halls for freshmen students. Jerome, Augustine and Gregory halls are all-female halls. These halls were last renovated in 1998, 1995, and 2014 respectively. Theresa and Madonna halls are all-male halls. These halls were renovated in 2000 and 1999 respectively. Clark Hall is the only co-ed dormitory and was built in 2010. The final hall is O'Connell Hall. Renovated in 2010, O'Connell Hall housing is based upon campus population housing needs for any given year. This hall may house new students, continuing students or a combination of both by floor if necessary.[88]

Tuition

The cost of attendance for the University of Dallas is dependent on the student's commuter status. For an on-campus student, the cost of attendance for the 2019–2020 school year is $59,600. For an off-campus resident in Texas, the cost of attendance for the 2019–2020 school year is $55,640. For a student living with parents or relatives, the cost of attendance for the 2019–2020 school year is $51,340.[89]

Criticism

The University of Dallas was criticized for a 2015 commencement ceremony in which speaker L. Brent Bozell III attributed the "destruction of the family" to gay marriage, saying that paganism and gay acceptance constituted anti-Christian bigotry taking over America.[90] The Princeton Review ranked the university as the 15th most LGBT-unfriendly school in the United States.[91]

Notable people

Alumni

Notable alumni include:

Intellectuals, artists and entertainers

- Larry Arnhart - Political theorist

- Jeffrey Bishop - Philosopher, physician and bioethicist (Director of the Albert Gnaegi Center for Health Care Ethics) at St. Louis University

- L. Brent Bozell III - Founder of Media Research Center and Fox News political commentator

- L. M. Kit Carson - Actor and screenwriter[92]

- Elizabeth (Betsy) DiSalvo, née James - Scholar in interactive computing and learning sciences and professor at Georgia Institute of Technology.

- John C. Eastman - Constitutional law scholar and Reagan Administration official

- Joe G. N. Garcia - Pulmonary scientist, medical researcher, academic administrator (at Johns Hopkins University) and physician

- Henry Godinez - Scholar of Latino theater at Northwestern University

- Lara Grice - American film actress known for The Mechanic (2011), The Final Destination (2009) and Déjà Vu

- Ernie Hawkins - Blues guitarist and singer

- Jason Henderson - Best-selling fantasy novelist and comic book author

- Thomas S. Hibbs - Philosopher and Honors College Dean at Baylor University, former President

- Andy Hummel - Bassist and songwriter for power-pop band Big Star

- Emily Jacir - Palestinian-American artist and activist

- Anita Jose - Professor, business strategist, essayist

- Joseph Patrick Kelly - Literary scholar focused on the works of James Joyce

- Peter MacNicol - Actor, notable performances include Ghostbusters, Ally McBeal, and Fox's 24[93]

- Patrick Madrid – Author, radio host and Catholic commentator

- William Marshner - Ethicist and theologian

- John McCaa - American television journalist

- Eric McLuhan - media theorist and son of Marshall McLuhan

- Trish Murphy - Singer-songwriter[94]

- Carl Olson - American journalist and Catholic writer

- Mackubin Thomas Owens - assistant dean of academics for Electives, Naval War College

- Tan Parker - Texas State Representative from Flower Mound and businessman

- Margot Roosevelt (attended, did not graduate) - American journalist at Orange County Register

- Gary Schmitt - public intellectual and co-founder of the Project for the New American Century

- Daryush Shokof - artist "Maximalism", Filmmaker "Amenic Film", Philosopher "Yekishim"

- Christopher Evan Welch - American actor famous for playing Peter Gregory in the HBO series Silicon Valley

- Gene Wolande - actor (L.A. Confidential) and television writer (The Wonder Years)

- Brantly Womack - professor of government and foreign affairs, University of Virginia

Business, politics and public affairs

- Miriem Bensalah-Chaqroun - Moroccan businesswoman and president of Confédération générale des entreprises du Maroc from 2012 to 2018[95]

- Robert Bunda - Hawaiian politician

- Suren Dutia - Business executive and entrepreneurship expert at Kauffman Foundation

- Emmet Flood - Special Counsel to President George W. Bush, 2007–2008[96]

- John H. Gibson - Senior Defense Department official and business executive

- Tadashi Inuzuka - Japanese politician and diplomat

- Katherine, Crown Princess of Yugoslavia - Wife of Alexander, Crown Prince of Yugoslavia

- Michael Neeb - CEO at HCA Healthcare UK

- Rosemary Odinga - Kenyan entrepreneur and activist

- Susan Orr Traffas - Former Head of the United States Children's Bureau

Religious leaders

- Oscar Cantú - Bishop of San Jose

- Michael Duca - Bishop of Baton Rouge

- Daniel E. Flores - Bishop of Brownsville

- David Konderla - Bishop of the Diocese of Tulsa

- Shawn McKnight - Bishop of Jefferson City

- Mark J. Seitz - Bishop of El Paso

Athletes

- Mike McPhee - NHL player and investment banker

- Tom Rafferty - Professional football player (offensive lineman for the Dallas Cowboys)

Faculty

The university's full-time, permanent faculty have included the following scholars:

- Mel Bradford - literary scholar and traditional conservative political theorist

- John Alexander Carroll- American historian and co-winner of the 1958 Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography for George Washington, Volumes I-VII

- Louise Cowan - literary critic, English professor and public intellectual

- Eugene Curtsinger - professor of English, novelist and academic administrator

- Willmoore Kendall - political theorist (mentor of William F. Buckley while teaching at Yale University)

- Thomas Lindsay - Texas Public Policy Foundation, Center for Higher Education

- Taylor Marshall - traditionalist Catholic writer, former Anglican priest, and one time philosophy professor

- Wilfred M. McClay - Intellectual historian and public intellectual[97]

- Joshua Parens - Philosopher concentrating on Islamic and Jewish medieval philosophy

- Philipp Rosemann - German philosopher specializing in continental and medieval philosophy

- Robert Skeris - American theologian and pioneering enthno-musicologist

- Janet E. Smith - classicist and philosopher

- Gerard Wegemer - literary scholar and the Director for The Center for Thomas More Studies[98]

- Thomas G. West - political theorist [99]

- Frederick Wilhelmsen - philosopher

Notable visiting or part-time faculty have included:

- Rudolph Gerken - former Archbishop of Santa Fe

- Caroline Gordon - American novelist and literary critic

- Magnus L. Kpakol - Chief Economic Advisor to the President of Nigeria

- Marshall McLuhan - Media theorist and philosopher (coined the expression "the medium is the message" )

- Bernard Orchard - British Biblical scholar and Benedictine monk

- Mitch Pacwa - American theologian and host of several shows on EWTN

- John Marini - political scientist studying American legislative and administrative politics

- Mark J. Seitz - Bishop of El Paso

- Jeffrey N. Steenson- prelate who converted to Catholicism from Anglicanism

References

- ^ a b "University of Dallas: 2016–2017 Bulletin" (PDF). Irving, TX: University of Dallas. 2016. p. 3. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ a b c d National Center for Education Statistics (2011), "University of Dallas", College Navigator, U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, retrieved September 22, 2011

- ^ University of Dallas: 2016–2017 Bulletin (PDF), Irving, TX: University of Dallas, 2016, p. 7, retrieved February 25, 2017

- ^ "Search Institutions Results", Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities, 2011, retrieved September 22, 2011

- ^ "Members", Council of Independent Colleges, 2017, retrieved February 25, 2017

- ^ "Member Institutions", National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities, 2011, retrieved September 22, 2011

- ^ https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/university-of-dallas-3651 [bare URL]

- ^ a b c d e "Institutional Profile", University of Dallas, University of Dallas, 2011, retrieved February 25, 2017

- ^ a b "University of Dallas : Overview". Usnews.com. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- ^ "Latitude and Longitude of a Point". iTouchMap.com. 2011. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

- ^ a b "City of Irving Comprehensive Plan Update, 2005 Report" (PDF). Irving, TX: City of Irving. 2005. p. 27. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

- ^ "UD Branding and Visual Identity Guidelines". Udallas.edu.

- ^ "Member Institutions", Southern Collegiate Athletic Conference, 2011, retrieved September 22, 2011

- ^ a b "Institution Details: University of Dallas", Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, Commission on Colleges, 2011, retrieved September 22, 2011

- ^ University of Dallas: 2016–2017 Bulletin (PDF), Irving, TX: University of Dallas, 2016–2017, pp. 4–6, retrieved February 25, 2017

- ^ National Center for Education Statistics (2011), "University of Dallas", College Navigator, U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, retrieved September 22, 2011

- ^ DeAndreis-Rosati Memorial Archives Holdings: University of Dallas (PDF), Chicago: DePaul University, 2005, pp. 1–2, retrieved September 22, 2011

- ^ "lost-colleges - (125)Holy Trinity College". America's Lost Colleges.

- ^ Jodziewicz, Thomas W., "Our Lady of Victory College", Handbook of Texas Online, The Texas State Historical Association, retrieved September 22, 2011

- ^ a b c Bannon, Louis, "University of Dallas", Handbook of Texas Online, The Texas State Historical Association, retrieved September 22, 2011

- ^ "A Little UD History and Prophecy". Steps in a Peregrine Rainscape. May 31, 2011. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ "The Founding of Our Lady of Dallas", Cistercian Abbey, Our Lady of Dallas, Cistercian Abbey, Our Lady of Dallas, 2011, retrieved September 22, 2011

- ^ "The History of Cistercian", Cistercian Preparatory School, Cistercian Preparatory School, 2011, retrieved September 22, 2011

- ^ Landregan, Steve (2011), "History: Catholic Schools in the Diocese of Dallas", Catholic Schools, Diocese of Dallas, Diocese of Dallas, retrieved September 22, 2011

- ^ "Provincials", School Sisters of Notre Dame, Dallas Province, School Sisters of Notre Dame, Dallas Province, 2011, retrieved September 22, 2011

- ^ "Fulbright Legacy", University of Dallas, 2010, retrieved November 2, 2013

- ^ "Anthony Kersting, BA '15, Becomes 39th UD Student to Earn Fulbright Award", University of Dallas, 2015

- ^ "University of Dallas – Phi Betta Kappa", University of Dallas, 2011, retrieved September 23, 2011

- ^ Hacker, Holly K. (August 29, 2016). "9 Texas colleges rank among the 'absolute worst' for LGBT students, gay rights group says". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ Rick Seltzer (June 1, 2017). "Clinging to the Core". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "Wanted: A New President for UD". D Magazine. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "TROUBLE at the University of Dallas? - The Catholic Thing". The Catholic Thing. March 3, 2011. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Crack in the Wall of Orthodoxy?". National Catholic Register. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ a b "What's next for UD?". The University News. April 17, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Faculty perspective: Dr. Susan Hanssen on the new college". The University News. April 5, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Dr. Malloy: a case against the New College". The University News. April 26, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ a b "Ousted University of Dallas president defends 8-year tenure as time of growth". Dallas News. April 17, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "University of Dallas struggles to find expansion direction amid questions of identity and curriculum". Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Scott Jaschik (April 16, 2018). "President Fired at University of Dallas". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ David, Stewart (Winter 2009). "Generation Gap" (PDF). Continuum: 1–7.

- ^ Brian, Melton (Winter 2008). "Laying a Foundation". Continuum: 8–12.

- ^ a b "Artwork showing Virgin Mary as stripper stirs up Catholic campus". Plainview Herald. March 8, 2008. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b "Artwork showing Virgin Mary as stripper stirs up Catholic campus". Waxahachie Daily Light. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "UD: The Mother of Jesus as Stripper". National Review. February 27, 2008. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ University of Dallas: 2016–2017 Bulletin (PDF), Irving, TX: University of Dallas, 2016, p. 12, retrieved February 25, 2017

- ^ "Controversial Student Organizations: Why They Should Not Be Recognized by a Catholic University - Crisis Magazine". Crisis Magazine. October 1, 1993. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

- ^ "University of Dallas board fires president but won't say why". Dallas News. April 13, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Sisson, Patrick (August 23, 2017). "O'Neil Ford: Texas's godfather of modern architecture". Curbed. Curbed. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ See Mary Carolyn Hollers George, O'Neil Ford, Architect (College Station, Tex.: Texas A&M University Press, 1992), 154, 236, 238.

- ^ a b "University of Dallas", The Princeton Review, 2017, retrieved February 25, 2017

- ^ "America's Ugliest College Campuses", Travel + Leisure, October 2013.

- ^ Orange Line Facts, Dallas Area Rapid Transit, retrieved September 23, 2011

- ^ a b National Center for Education Statistics (2015), "University of Dallas", College Navigator, U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, retrieved February 25, 2017

- ^ "University of Dallas 2011". UCAN. Retrieved April 13, 2012.

- ^ "Undergraduate Cost of Attendance", University of Dallas, University of Dallas, 2016, retrieved February 25, 2017

- ^ "University of Dallas", College Navigator, U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, 2015, retrieved February 25, 2017

- ^ a b "Classes in the Core". Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- ^ "The Great Books".

- ^ ""A" List". Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ "IPS Core Curriculum". Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- ^ "Engineering Requirements". udallas.edu.

- ^ "Rome and Summer Programs". Udallas.edu.

- ^ "2024 Master's Universities Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "2023-2024 Best Regional Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 18, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2024". Forbes. September 6, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ Princeton Review Labels Three Texas Universities as LGBT-Unfriendly, 2017, retrieved September 17, 2018

- ^ "University of Dallas, Overall Rankings", U.S. News & World Report, 2022, retrieved May 7, 2021

- ^ "Master's University Rankings 2014", Washington Monthly, 2015, retrieved February 25, 2017

- ^ "Top Universities Regional West", Webometrics Ranking Web of World Universities, 2012, retrieved March 14, 2012

- ^ "University of Dallas", Forbes, 2019, archived from the original on August 2, 2015, retrieved May 7, 2021

- ^ "University of Dallas", What Will They Learn?, 2011, retrieved September 22, 2011

- ^ Recommended Colleges, Manassas, VA: The Cardinal Newman Society, 2016, retrieved October 29, 2013

- ^ "University of Dallas - Cardinal Newman Society". Cardinal Newman Society. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

- ^ Honan, William H. (September 6, 1998). "A Right-Wing Slant on Choosing the Right College". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

- ^ Best Fine Arts Schools 2016, U.S. News & World Report, 2016, retrieved February 25, 2017

- ^ "Assessment of Research Doctorate Programs", National Research Council, 2010, retrieved September 23, 2011

- ^ "English Language and Literature Rankings". PhDs.org Graduate School Guide. Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- ^ "Philosophy Rankings". PhDs.org Graduate School Guide. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ "Political Science Rankings". PhDs.org Graduate School Guide. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ Moore, Matthew J. (April 2010), "Political Theory Today: Results of a National Survey" (PDF), PS: Political Science & Politics: 271, retrieved September 22, 2011

- ^ Dallas Medieval Texts & Translations. "Dallas Medieval Texts & Translations | Home". Dallasmedievaltexts.org. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ^ Novinski, Lyle (2017). "Personal Notes: on Pat Haggerty".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Novinski, Lyle (2017). "Personal Notes: The Haggerty Art Village".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Crusader | Joe Staler Student Publications Collection | University of Dallas". digitalcommons.udallas.edu. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "Ramify | About". www.ramify.org. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ Feltl, Elsa. ""The Mockingbird" magazine takes flight | The University News". udallasnews.com. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "University Scholar Journal". udallas.edu. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "Residence Halls". udallas.edu. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "Cost". Udallas.edu.

- ^ O'Donnell, Carey (May 28, 2015). "University Of Dallas Student Demands School's President Apologize For Anti-Gay Commencement Speech". NewNowNext. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ Washeck, Angela (January 21, 2013). "Princeton Review Labels Three Texas Universities as LGBT-Unfriendly". Texas Monthly. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ Simek, Peter (June 2, 2011). "Why 'David Holzman's Diary' Still Matters | FrontRow". Frontrow.dmagazine.com. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ^ "Peter MacNicol Biography". TV Guide. Retrieved January 25, 2007.

- ^ "Trish Murphy – Free listening, videos, concerts, stats and pictures at". Last.fm. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ^ Le Bec, Christophe (May 16, 2012). "Maroc – CGEM : Meriem Bensalah Chaqroun élue patronne des patrons". Jeune Afrique (in French). Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ "Williams & Connolly: Emmet T. Flood profile". Wc.com. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ^ "Wilfred McClay". Utc.edu. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ^ "About us". The Center for Thomas More Studies. 2015.

- ^ "Hillsdale College - Faculty Profile". www.hillsdale.edu. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012.

Further reading

- University of Dallas: 50 Years of Vision & Courage, 1956–2006 (Irving, Tex.: University of Dallas, 2006). ISBN 978-0-9789075-0-1. 165 pp.

- The University of Dallas honoring William A. Blakley (Irving, Tex.: University of Dallas, 1966). 19 pp.

External links

- Official website

- University of Dallas Athletics website

- The University News – student newspaper

- Articles with bare URLs for citations from January 2022

- University of Dallas

- Buildings and structures in Irving, Texas

- Education in Irving, Texas

- Educational institutions established in 1956

- Universities and colleges accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools

- Universities and colleges in Dallas County, Texas

- Universities and colleges in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex

- USCAA member institutions

- Catholic universities and colleges in Texas

- Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities

- 1956 establishments in Texas