LZ 129 Hindenburg: Difference between revisions

→Commercial and passenger operations: plebiscite is totally unrelated to first commercial flight, and it's mention is only inflammatory |

→Commercial and passenger operations: need to follow WP:MOS |

||

| Line 71: | Line 71: | ||

[[Image:Zeppelin Passenger Pins.jpg|thumb|right|150px|Zeppelin passenger lapel pins]] |

[[Image:Zeppelin Passenger Pins.jpg|thumb|right|150px|Zeppelin passenger lapel pins]] |

||

On March 4, 1936, the ''Hindenburg'' made its first commercial flight, a transatlantic passage to [[Rio de Janeiro]].<ref>Mooney 1972, pp. 82–85.</ref> For the first time since the death of Count Zeppelin, however, Hugo Eckener was not the commander and had no operational control over the airship on which he was only to be a passenger, while Captain Lehmann commanded the ship. Upon arrival in Rio, |

On March 4, 1936, the ''Hindenburg'' made its first commercial flight, a transatlantic passage to [[Rio de Janeiro]].<ref>Mooney 1972, pp. 82–85.</ref> For the first time since the death of Count Zeppelin, however, Hugo Eckener was not the commander and had no operational control over the airship on which he was only to be a passenger, while Captain Lehmann commanded the ship. Upon arrival in Rio, Eckener learned from an Associated Press Service reporter that Goebbles had followed through on his threat made the previous week and issued orders that Eckener's name would "no longer be mentioned in German newspapers and periodicals" and "no pictures nor articles about him shall be printed."<ref>Mooney 1972, p. 86.</ref> |

||

During the outbound flight to Rio, one of the ''Hindenburg's'' four [[Daimler-Benz]] 16-cylinder [[diesel engine]]s broke down because of a wrist-pin breakage, and while repairs were made at [[Recife]] it was no longer able deliver full power. A similar problem developed on the return journey in another engine, and while mechanics attempted to repair it a third also broke down. By then running on just two of its four powerplants, the ''Hindenburg'' almost drifted into the Sahara Desert where it potentially could have been lost in a crash or forced landing. To avoid such a catastrophe, the crew instead raised the airship in search of counter-trade winds which were usually above {{convert|5000|ft}} even though this was well beyond its pressure height. Fortunately the ''Hindenburg'' found a wind at {{convert|3600|ft}} to bring it safely back to Friedrichshafen. The two engines restored partial power after repairs were made and were later overhauled. No subsequent problems occurred with either engine.<ref>Lehmann 1937, pp. 341-342.</ref> |

During the outbound flight to Rio, one of the ''Hindenburg's'' four [[Daimler-Benz]] 16-cylinder [[diesel engine]]s broke down because of a wrist-pin breakage, and while repairs were made at [[Recife]] it was no longer able deliver full power. A similar problem developed on the return journey in another engine, and while mechanics attempted to repair it a third also broke down. By then running on just two of its four powerplants, the ''Hindenburg'' almost drifted into the Sahara Desert where it potentially could have been lost in a crash or forced landing. To avoid such a catastrophe, the crew instead raised the airship in search of counter-trade winds which were usually above {{convert|5000|ft}} even though this was well beyond its pressure height. Fortunately the ''Hindenburg'' found a wind at {{convert|3600|ft}} to bring it safely back to Friedrichshafen. The two engines restored partial power after repairs were made and were later overhauled. No subsequent problems occurred with either engine.<ref>Lehmann 1937, pp. 341-342.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 03:00, 7 May 2010

| Hindenburg | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hindenburg | |

| Type | Hindenburg-class airship |

| Manufacturer | Luftschiffbau Zeppelin |

| Construction number | LZ 129 |

| Manufactured | 1931-36 |

| Registration | D-LZ129 |

| First flight | March 4, 1936 |

| Owners and operators | Deutsche Zeppelin Reederei |

| In service | 1936-37 |

| Fate | Destroyed in fire May 6, 1937 |

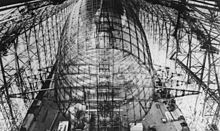

LZ 129 Hindenburg (Deutsches Luftschiff Zeppelin #129; Registration: D-LZ 129) was a large German commercial passenger-carrying rigid airship, the lead ship of the Hindenburg class, which were the longest (245 meters, 803.8 feet) flying machines of any kind as well as the largest airships by envelope volume (200,000 m³, 7,062,000 cubic feet).[1] The airship flew from March 1936 until destroyed by fire 14 months later on May 6, 1937, at the end of the first North American transatlantic journey of its second season of service. Thirty-six people died in the accident, which occurred while landing at Lakehurst Naval Air Station in Manchester Township, New Jersey.

The Hindenburg was named after the late Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg (1847–1934), President of Germany (1925–1934).

Design and development

The Hindenburg had a Duralumin structure, incorporating 15 Ferris wheel-like bulkheads along its length with 16 cotton gas bags fitted between these, and bulkheads braced to each other by longitudinal girders placed around their circumferences. The airship's skin was of cotton doped with a mixture of reflective materials intended to protect the gas bags within from both ultraviolet (which would damage them) and infrared (which might cause them to overheat). Records of the Zeppelin company indicate that in 1931 it purchased 5,000 kg of duralumin salvaged from the wreckage of the October 1930 crash of the British airship R101 all or some of which may have been to re-cast and used in the construction of the Hindenburg.[2]

The interior furnishings of the Hindenburg were designed by Professor Fritz August Breuhaus, whose design experience included Pullman coaches, ocean liners, and warships of the German Navy.[3] The upper A Deck contained small passenger quarters in the middle flanked by large public rooms: a dining room to port as well as a lounge and writing room to starboard. Paintings on the walls of the dining room portrayed the Graf Zeppelin's trips to South America. A stylized world map covered the wall of the lounge. Long slanted windows ran the length of both decks. The passengers were expected to spend most of their time in the public areas rather than their cramped cabins.[4]

The lower B Deck contained washrooms, a mess hall for the crew, and a smoking lounge. Recalled Harold G. Dick, an American representative from the Goodyear Zeppelin Corporation, "The only entrance to the smoking room, which was pressurized to prevent the admission of any leaking hydrogen, was via the bar, which had a swiveling air lock door, and all departing passengers were scrutinized by the bar steward to make sure they were not carrying out a lighted cigarette or pipe."[5]

Use of hydrogen instead of helium

Helium was initially selected[6] for the lifting gas because it was the safest to use in airships, as it is not flammable. At the time it was extremely expensive, and was available from natural gas reserves in the United States. Hydrogen, by comparison, could be cheaply produced by any industrialized nation and has somewhat more lift. The American rigid airships using helium were forced to conserve the gas at all costs and this hampered their operation.[7] While a hydrogen-filled ship could routinely valve gas as necessary, a helium-filled ship had to resort to dynamic force if it was too light to descend, a measure which took a toll on its structure[citation needed].

Despite a ban the U.S. had imposed on helium exports, the Germans nonetheless designed the ship to use the gas in the belief that the ban would be lifted; however, the designers learned as they were working to complete the project that the ban was to remain in place, forcing them to re-engineer the Hindenburg to use hydrogen for lift[8]. Although the danger of using inflammable hydrogen was obvious, there were no alternative gases that could be produced in sufficient quantities that would provide sufficient lift. One beneficial side effect of employing hydrogen was that more passenger cabins could be added. The Germans' long history of flying hydrogen-filled passenger airships without a single injury or fatality engendered a widely held belief they had mastered the safe use of hydrogen. The Hindenburg's first season performance appeared to demonstrate this.

Operational history

Five years after construction began in 1931, the Hindenburg made its maiden flight at Friedrichshafen on March 4, 1936, with 87 souls on board[9] consisting of Zeppelin Company chairman Hugo Eckener as commander, Lt. Col. Joachim Breithaupt representing the German Air Ministry, the Zeppelin company's eight airship captains, 47 other crew members, and 30 employees of the Zeppelin dockyards who flew as passengers.[10] After making five more "shake down" flights over the next three weeks, the airship made its formal public debut with a three-day, 4,100 miles (6,598 km) propaganda flight around Germany (Die Deutschlandfahrt) which it made jointly with the Graf Zeppelin from March 26 to 29.[11] Two days later, the new airship made its first commercial flight as it departed Löwental on March 31 on a four-day transatlantic voyage to Rio de Janeiro.[12]

The airship was operated commercially by the Deutsche Zeppelin Reederei GmbH (DZR), which had been established by Hermann Göring in March, 1935 to increase Nazi influence over zeppelin operations.[13] The DZR was jointly owned by the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin, the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (German Air Ministry), and Deutsche Lufthansa AG, and also operated the Graf Zeppelin during its last two years of commercial service to South America from 1935 to 1937. The Hindenburg and its sister ship, the D-LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II (launched: September, 1938), were the only two airships ever purpose-built for regular commercial transatlantic passenger operations, although the latter never entered passenger service before being scrapped in 1940.

Die Deutschlandfahrt

The Hindenburg's first "official" function was not to be in the commercial transatlantic passenger service for which it was designed and built. Instead the airship was used as a vehicle for Nazi propaganda. Three days after its first test flight on March 4, 1936, troops of the German Reich occupied the Rhineland, a region that abutted the borders with the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Belgium, and France. The area had been specified in the 1920 Treaty of Versailles as a de-militarized zone in order to provide a buffer between Germany and the neighboring countries. In order to then justify the remilitarization of the Rhineland (which was a violation of the 1925 Locarno Pact[14]), a plebiscite was quickly called by Hitler for March 29 to ask the German people to ratify the Rhineland occupation. The Hindenburg and the Graf Zeppelin were designated to be a key part of the process.

For the four days prior to the balloting, German Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels ordered the two airships to fly in tandem over Germany on a "Hitler Re-election and Rhineland Referendum Flight" (Deutschlandfahrt), taking off together from Friedrichshafen on the morning of March 26.[15] It was during March 24–25 that the name Hindenburg was painted on the hull, although it had been named that by Eckener over a year earlier.[16] This greatly angered Goebbles, who quickly summoned Eckener to Berlin and informed him that he wanted the airship to be renamed Adolph Hitler. When Eckener refused to change the name, the propaganda minister decreed that it would be referred to in Germany only as "LZ 129" and threatened to make Eckener a "non-person" in the German media.[17] There was no christening ceremony for the Hindenburg.[citation needed]

Wind conditions were not good for takeoff that morning, but the Hindenburg's commander, Captain Ernst Lehmann, was determined to impress the politicians that were present on the field by rushing the takeoff. As the airship began to rise in a majestic manner with full engine power, a gust of wind hit the ship and the lower tail fin hit the ground, damaging the rear end of the fin.[18] Eckener was furious and rebuked Lehmann:

How could you, Mr Lehmann, order the ship to be brought out in such windy conditions? You had the best excuse in the world for postponing this idiotic flight; instead, you risk the ship, merely to avoid annoying Mr Goebbels. Do you call this showing a sense of responsibility towards our enterprise?[19]

The Graf Zeppelin thus left alone on the propaganda mission while temporary repairs were made to the Hindenburg, which then joined the smaller airship later that day.[20] As millions of Germans watched from below, the two giants of the sky flew throughout Germany for the next four days and nights dropping propaganda leaflets, blaring martial music and slogans from large loudspeakers, and broadcasting election speeches from a makeshift radio studio on board the Hindenburg.[21]

Commercial and passenger operations

On March 4, 1936, the Hindenburg made its first commercial flight, a transatlantic passage to Rio de Janeiro.[22] For the first time since the death of Count Zeppelin, however, Hugo Eckener was not the commander and had no operational control over the airship on which he was only to be a passenger, while Captain Lehmann commanded the ship. Upon arrival in Rio, Eckener learned from an Associated Press Service reporter that Goebbles had followed through on his threat made the previous week and issued orders that Eckener's name would "no longer be mentioned in German newspapers and periodicals" and "no pictures nor articles about him shall be printed."[23]

During the outbound flight to Rio, one of the Hindenburg's four Daimler-Benz 16-cylinder diesel engines broke down because of a wrist-pin breakage, and while repairs were made at Recife it was no longer able deliver full power. A similar problem developed on the return journey in another engine, and while mechanics attempted to repair it a third also broke down. By then running on just two of its four powerplants, the Hindenburg almost drifted into the Sahara Desert where it potentially could have been lost in a crash or forced landing. To avoid such a catastrophe, the crew instead raised the airship in search of counter-trade winds which were usually above 5,000 feet (1,500 m) even though this was well beyond its pressure height. Fortunately the Hindenburg found a wind at 3,600 feet (1,100 m) to bring it safely back to Friedrichshafen. The two engines restored partial power after repairs were made and were later overhauled. No subsequent problems occurred with either engine.[24]

The Hindenburg made 17 round trips across the Atlantic Ocean in 1936, its first and only full year of service, with 10 trips to the U.S. and seven to Brazil. In July 1936, the airship also completed a record Atlantic double crossing in five days, 19 hours and 51 minutes. After defeating Joe Louis, the German boxer Max Schmeling returned home on the Hindenburg to a hero's welcome in Frankfurt.[25] The airship flew 308,323 kilometres (191,583 mi) with 2,798 passengers and 160 tons of freight and mail during the season, and its success encouraged the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin Company to plan the expansion of its airship fleet and transatlantic services.

One year to the day before it crashed, the Hindenburg departed Germany on May 6 on its first of 10 North American flights in 1936, arriving in Lakehurst, New Jersey, three days later. Passengers observed that the ship was so stable (a pen or pencil reportedly could be stood on a table without falling) that some missed the takeoff and believed the ship was still on the ground. The cost of a ticket between Germany and Lakehurst was US$400 (about US$5,900 in 2008 dollars[26]), which was a considerable sum for the Depression era. Hindenburg passengers were generally affluent, including many leaders of industry.

From time to time the Hindenburg was used for propaganda purposes. On August 1st it flew over of the Olympic Stadium (Olympiastadion) in Berlin during the opening ceremonies of the 1936 Summer Olympic Games. Shortly before the arrival of Adolf Hitler to declare the Games open, the airship crossed low over the packed massive stadium while trailing the Olympic flag on a long weighted line suspended from its gondola.[27]

During its first year in service, the airship had a special aluminium Blüthner grand piano placed on board in the music salon. It was the first piano ever[citation needed] placed in flight and helped host the first radio broadcast "air concert." The piano was removed after the first year to save weight.[28]

Over the winter of 1936–37, several changes were made. The greater lift capacity allowed 10 passenger cabins to be added, nine with two beds and one with four beds, increasing the total passenger capacity to 72.[29] In addition, "gutters" were installed to collect rain for use as water ballast.

Final flight

After making its first South American flight of the 1937 season in late March, the Hindenburg left Frankfurt for Lakehurst, New Jersey on the evening of May 3 on its first scheduled round trip between Europe and the United States that season. Although strong headwinds slowed the crossing, the flight had otherwise proceeded routinely as it approached for a landing three days later.[30]

Around 7:00 p.m. local time on May 6, at an altitude of 650 ft (200 m), Hindenburg approached Naval Air Station Lakehurst with Captain Max Pruss at the helm. Twenty-five minutes later, the airship caught fire and crashed, completely engulfed in flames, in only 37 seconds. Of the 36 passengers and 61 crew on board, 13 passengers and 22 crew died. One member of the ground crew was also killed, making a total of 36 lives lost in the disaster.

The location of the initial fire, the source of ignition, and the initial source of fuel remain subjects of debate. The cause of the accident has never been determined, although many theories have been proposed. Escaping hydrogen gas will burn after mixing with air. The covering also contained material (such as cellulose nitrate and aluminum flakes) which some experts claim are highly flammable.[31] This, however, is highly controversial and has been rejected by some researchers because the outer skin burns too slowly to account for the rapid flame propagation.[30] The duralumin framework of the Hindenburg was salvaged and shipped back to Germany. There the scrap was recycled and used in the construction of military aircraft for the Luftwaffe, as were the frames of the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin and LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II when they were scrapped in 1940.[32]

Notable appearances in media

- Actual footage of the Hindenburg is shown in the 1937 Charlie Chan film Charlie Chan at the Olympics, which depicts Chan onboard for a flight across the Atlantic to attend the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. The movie was released 15 days after the actual Hindenburg disaster on May 21, 1937.

- The image of the airship exploding was used as the cover of Led Zeppelin's self-titled debut album.

- The plot of the third book of the Pendragon fantasy book series, The Never War is based on the Hindenburg disaster.

- The Hindenburg (film) presents a dramatic re-telling (1975).

- In the original theatrical release of the film Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Indiana Jones travels on the Hindenburg. The name was digitally removed from the Zeppelin's fixtures in subsequent releases, apparently because the film's events took place in 1938 and the Hindenburg was actually destroyed a year earlier in 1937. Jones also escapes the zeppelin via a trapeze-mounted parasite fighter biplane, a system never successfully installed on the Hindenburg or any German airship.[33]

Specifications

General characteristics

- Crew: 40 to 61

- Capacity: 50-72 passengers

Performance Source: [1]

See also

- Hindenburg class airship

- Harold G. Dick was an American engineer who flew on most of the Hindenburg flights.

- The Zeppelin Museum Friedrichshafen displays a reconstruction of a 33 m section of the Hindenburg.

- Timeline of hydrogen technologies

References

- Notes

- ^ a b "Hindenburg Statistics", airships.net, 2009, Retrieved 6 May, 2010

- ^ R101 - the Final Trials and Loss of the Ship The Airship Heritage Trust

- ^ Lehmann 1937, p. 319.

- ^ Dick and Robinson 1985, p. 96.

- ^ Dick and Robinson 1985, p. 97.

- ^ Anne MacGregor (2001). The Hindenburg Disaster: Probable Cause (Documentary). Moondance Films/Discovery Channel.

- ^ Vaeth 2005, p. 38.

- ^ MacGregor. Op. cit.

- ^ "Souls on board" is a long standing technical term used in aviation and maritime contexts to designate the total number of living persons making up the passengers (men, women, children, and infants) and crew on board an aircraft in flight or a vessel at sea.

- ^ Lehmann 1937, p. 323.

- ^ Lehmann 1937, pp. 323–332.

- ^ Lehmann 1937, p. 341.

- ^ "Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei (DZR)" Airships.net

- ^ BELGIUM INSISTENT ON LOCARNO TERMS The New York Times. Mar 12, 1936

- ^ "Photograph of the Hindenburg and Graf Zeppelin preparing to depart Freidrichshafen on Die Deutschlandfahrt." specialcollections.wichita.edu. Retrieved: January 11, 2010.

- ^ "The Airship." British Quarterly Journal, Spring, 1935.

- ^ Mooney 1972, p. 77-78.

- ^ "Photograph by Harold Dick of damaged lower vertical tail fin." specialcollections.wichita.edu. Retrieved: January 11, 2010.

- ^ Eckener 1958, pp. 150–151.

- ^ "Photograph by Harold Dick of temporary repair to lower vertical tail fin." specialcollections.wichita.edu. Retrieved: January 11, 2010.

- ^ Lehmann 1937, pp. 326–332.

- ^ Mooney 1972, pp. 82–85.

- ^ Mooney 1972, p. 86.

- ^ Lehmann 1937, pp. 341-342.

- ^ Berg, Emmett. "Fight of the Century". Humanities, Vol. 25, No. 4, July/August 2004. Retrieved: January 7, 2008.

- ^ "Data." data.bls.gov. Retrieved: January 11, 2010.

- ^ Birchall 1936

- ^ "A History of the Blüthner Piano Company". bluthnerpiano.com. Retrieved: January 7, 2008.

- ^ Mooney 1972, p. 95.

- ^ a b "Cause of the Hindenburg Disaster." Aerospaceweb.org. Retrieved: January 11, 2010.

- ^ "Hydrogen Exonerated in Hindenburg Disaster." hydrogenus.com. Retrieved: January 11, 2010.

- ^ Mooney 1972, p. 262.

- ^ " 'Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade'." imdb.com. Retrieved: January 11, 2010.

- Bibliography

- Archbold, Rick. Hindenburg: An Illustrated History. Toronto: Viking Studio/Madison Press, 1994. ISBN 0-670-85225-2.

- Birchall, Frederick. "100,000 Hail Hitler; U.S. Athletes Avoid Nazi Salute to Him". The New York Times, 1 August 1936, p. 1.

- Botting, Douglas. Dr. Eckener's Dream Machine: The Great Zeppelin and the Dawn of Air Travel. New York: Henry Holt & Co., 2001. ISBN 0-80506-458-3.

- Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederi. Airship Voyages Made Easy (16 page booklet for "Hindenburg" passengers). Luftschiffbau Zeppelin G.m.b.H., Friedrichshafen, Germany, 1937.

- Dick, Harold G. and Douglas H. Robinson. The Golden Age of the Great Passenger Airships Graf Zeppelin & Hindenburg. Washington, D.C. and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985. ISBN 1-56098-219-5.

- Duggan, John. LZ 129 "Hindenburg": The Complete Story. Ickenham, UK: Zeppelin Study Group, 2002. ISBN 0-9514114-8-9.

- Hoehling, A.A. Who Destroyed The Hindenburg? Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1962. ISBN 0-44508-347-6.

- Eckener, Dr. Hugo, translated by Dr. Douglas Robinson. My Zeppelins. London: Putnam & Co. Ltd., 1958.

- Lehmann, Ernst. Zeppelin: The Story of Lighter-than-air Craft. London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1937.

- Majoor, Mireille. Inside the Hindenburg. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 2000. ISBN 0-316-123866-2.

- Mooney, Michael Macdonald. The Hindenburg. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1972. ISBN 0-396-06502-3.

- National Geographic. Hindenburg's Fiery Secret (DVD). Washington, DC: National Geographic Video, 2000.

- Vaeth, Joseph Gordon. They Sailed the Skies: U.S. Navy Balloons and the Airship Program. Annapolis MD: Naval Institute Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1591149149.

External links

Video

- "Hindenburg - End Of A Successful Voyage (Standard 4:3) (1937)". Pathgrams. Retrieved 2009-02-21. (shows docking team, passengers)

- "Hindenburg - Passengers Disembarking (Standard 4:3) (1937)". Pathgrams. Retrieved 2009-02-21. (passengers descend ramp)

Articles

- Technical Drawing of the LZ 129 Hindenburg

- Airships.net: Detailed history and photographs of interior and exterior of LZ-129 Hindenburg

- eZEP.de — The webportal for Zeppelin mail and airship memorabilia

- Hindenburg: Sky Cruise. Illustrated account of a flight on the Hindenburg - with maiden voyage and final flight passenger lists

- Page at Great Zeppelins website, with various pictures

- Harold G. Dick Airship Collection (Harold G. Dick was an American engineer who flew on most Hindenburg flights.)

- ZLT Zeppelin Luftschifftechnik GmbH & Co KG. The company is still in the airship business today.

- The Hindenburg at Navy Lakehurst Historical Society