Chord (music): Difference between revisions

tags |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Classical spectacular07.jpg|thumb|right|300px|[[Musical instrument|Instruments]] and voices playing different [[note]]s create chords.]] |

[[File:Classical spectacular07.jpg|thumb|right|300px|[[Musical instrument|Instruments]] and voices playing different [[note]]s create chords.]] |

||

{{Refimprove}} |

|||

{{technical}} |

|||

:''This article describes pitch simultaneity and harmony in music. For other meanings of the word, see [[Chord]].'' |

:''This article describes pitch simultaneity and harmony in music. For other meanings of the word, see [[Chord]].'' |

||

Revision as of 19:44, 11 September 2010

This article needs additional citations for verification. |

This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. |

- This article describes pitch simultaneity and harmony in music. For other meanings of the word, see Chord.

In music, a chord is any set of harmonically-related notes that is heard as if sounding simultaneously (a "harmonic simultaneity"). The most frequently encountered chords in theory and music are triads.

Triads are so called because they consist of three distinct notes: further notes may be added to give extended chords and added tone chords. Chords are also commonly classed by their root note so, for instance, the chord C Major may be described as a three-note chord built upon the note C. The term major is referred to as the chord (or chordal) quality. Other chord qualities include minor, augmented, diminished, half-diminished, and dominant.

Since the structural meaning of a chord depends exclusively upon the degree of the scale upon which it is built,[1] chords are often analysed by numbering them, using Roman numerals, upwards from the key-note. A chord may also be classified by its inversion, the order in which its notes are stacked from lowest to highest.

A chord, then, is the harmonic or "vertical" function of any group of notes. These need not actually be played together: arpeggios and broken chord figures may for many practical and theoretical purposes be understood as chords. There are four common ways of notating or representing chords as such[2]: Roman numerals are commonly used in harmonic analysis to denote the step of the scale upon which the chord is built and its quality. Figured bass, much used in the Baroque era, added numbers to a written bass line to enable keyboard players to improvise chords with the right hand while playing the bass with their left. Macro symbols are a technique of modern musicology while various popular music symbols, such as chord charts for guitarists, can quickly lay out the harmonic groundplan of a piece so that the musician may improvise, "jam", or "vamp" on a part.

in just intonation

in Equal temperament in Lucy tuning

in 1/4-comma meantone

in Young temperament

in Pythagorean tuning

Definition and history

The English word "chord" derives from "cord", a Middle English shortening of "accord" in the sense of "in tune with one another". For a sound configuration to be recognized as a chord it must have a certain duration.

Since a chord may be understood as such even when all its notes are not simultaneously audible there has been some academic discussion regarding the point at which a group of notes can be called a chord. Jean-Jacques Nattiez (1990, p. 218) explains that "we can encounter 'pure chords' in a musical work," such as in the "Promenade" of Modest Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition but "often, we must go from a textual given to a more abstract representation of the chords being used" - as in Claude Debussy's Première Arabesque.

Early Christian harmony featured the perfect intervals of a fourth, a fifth, and an octave. In the 15th and 16th centuries, the major and minor triads became increasingly common, and were soon established as the default sonority for Western music. Such triads can be described as a series of three notes; the root note, the "third", and the "fifth" of the chord. As an example, the C major scale consists of the notes C D E F G A B C while the chord of C Major - the major triad formed using the note C as the root - consists of C itself (the root note of the scale), E (the third note of the scale) and G (the fifth note of the scale). This triad is major because the interval from C to E, of four semitones, is a major third. Using the same scale a chord may be constructed using the D as the root note; D (root), F (third), A (fifth). While there were four semitones between the root and third of the chord on C, in the D chord there are only 3 semitones between the root and third (the outer notes are still a perfect fifth apart). Thus, while the C triad is major, the D triad is minor. A triad can be constructed on any note of the C major scale and all will be minor or major, with the exception of the triad on the leading-tone which is diminished.

Taking any other major scale (Ionian mode), the first, fourth and fifth intervals, when used as roots, form major triads. Similarly, as any major scale can also yield a relative minor, in any natural minor scale (Aeolian mode) minor triads are found on the tonic, fourth and fifth degrees of the scale. Each seven-note diatonic scale can provide three major and three minor chords, both sets of three standing in the same I-IV-V relationship to one another. The seventh degree of the major (degree two of the relative minor) will result in a diminished chord. See Music and mathematics#Mathematics of musical scales.

Four-note "seventh chords" were widely adopted from the 17th century. The harmony of many contemporary popular Western genres continues to be founded in the use of triads and seventh chords, though far from universally. Notable exceptions include chromatic, atonal or post-tonal contemporary classical music (including the music of some film scores) and modern jazz (especially circa 1960), in which chords often include at least five notes, with seven (and occasionally more) being quite common.

Polychords are formed by two or more chords superimposed. Often these may be analysed as extended chords but some examples lack the tertian sonority of triads (See: altered chord, secundal chord, quartal and quintal harmony and Tristan chord). A nonchord tone is a dissonant or unstable tone that lies outside the chord currently heard, though often resolving to a chord tone. A succession of chords is called a chord progression.

Chord characteristics

Every chord has certain characteristics, which include:

- Number of pitch classes (distinct notes without respect to octave) that constitute the chord.

- Scale degree of the root note

- Position or inversion of the chord

- General type of intervals it contains: for example seconds, thirds, or fourths

Number of distinct notes

Chords may be classified according to the number of notes they contain. More precisely, since instances of any given note in different octaves may be taken as the same note for the purposes of analysis, it is better to speak of the number of distinct pitch classes used in their construction. Three such pitch classes are needed to define any common chord, therefore the simultaneous sounding of two notes is sometimes classed as an interval rather than a chord. Hence Andrew Surmani (2004, p. 72) states; "when three or more notes are sounded together, the combination is called a chord" and George T. Jones (1994, p. 43) explains; "two tones sounding together are usually termed an interval, while three or mores tones are called a chord" while, according to Monath (1984, p. 37); "A chord is a combination of three or more tones sounded simultaneously for which the distances (called intervals) between the tones are based on a particular formula."

Chords, however, are so well-established in Western music that sonorities of two pitches, or even single-note melodies, are commonly heard as "implying" chords, a psychoacoustic phenomenon resulting from a lifetime of exposure to the conventional harmonies of music so that the brain "completes" the chord.[3] Otto Karolyi[4] writes that "two or more notes sounded simultaneously are known as a chord."

Two-note combinations, whether referred to as chords or intervals, are called dyads. Chords constructed of three notes of some underlying scale are described as triads. They may be understood to be constructed from a stack of two third intervals. Chords of four notes are known as tetrads, those containing five are called pentads and those using six are hexads. Sometimes the terms "trichord", "tetrachord", "pentachord" and "hexachord" are used, though these more usually refer to the pitch classes of any scale, not generally played simultaneously. Chords that may contain more than three notes include suspended chords, pedal point chords, dominant seventh chords and others termed extended chords, added tone chords, clusters, and polychords.

Scale degree

In the key of C major the first degree of the scale, called the tonic, is the note C itself, so a C major chord, a triad built on the note C, may be called the one chord of that key and notated in Roman numerals as I. The same C major chord can be found in other scales: it forms chord III in the key of A minor (A-B-C) and chord IV in the key of G major (G-A-B-C). This numbering lets us see the job a chord is doing in the current key and tonality.

Many analysts use lower-case Roman numerals to indicate minor triads and upper-case for major ones, and "degree" and "plus" signs ( o and + ) to indicate diminished and augmented triads respectively. Otherwise all the numerals may be upper-case and the qualities of the chords inferred from the scale degree. Chords outside the scale can be indicated by placing a flat/sharp sign before the chord — for example, the chord of E flat major in the key of C major is represented by ♭III. The tonic of the scale may be indicated to the left (e.g. F♯:)or may be understood from a key signature or other contextual clues. Indications of inversions or added tones may be omitted if they are not relevant to the analysis. Roman numerals indicate the root of the chord as a scale degree within a particular major key as follows:

| Roman numeral | I | ii | iii | IV | V | vi | viio/bVII |

| Scale degree | tonic | supertonic | mediant | subdominant | dominant | submediant | leading tone/subtonic |

When a chord is analysed as "borrowed" from another key it may be shown by the Roman numeral corresponding with that key after a slash so, for example, V/V indicates the dominant chord of the dominant key of the present home-key. The dominant key of C major is G major so this secondary dominant will be the chord of the fifth degree of the G major scale, which is D major. If used, this chord will cause a modulation.

Inversion

In the harmony of Western art music a chord is said to be in root position when the tonic note is the lowest in the chord, and the other notes are above it. When the lowest note is not the tonic, the chord is said to be inverted. Chords, having many constituent notes, can have many different inverted positions as shown below for the C major chord:

| Bass Note | Position | Order of notes | Notation |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | root position | C E G | as G is a 5th above C and E is a 3rd above C |

| E | 1st inversion | E G C | as C is a 6th above E and G is a 3rd above E |

| G | 2nd inversion | G C E | as E is a 6th above G and C is a 4th above G |

Further, a four-note chord can be inverted to four different positions by the same method as triadic inversion.

Secundal, tertian, and quartal chords

Many chords can be arranged as a series of ascending notes separated by intervals of roughly the same size. For example the C major triad's notes, C, E, and G, can be arranged in the series C-E-G, the first interval (C-E) being a major third and the second (E-G) a minor third. Any such chord that can be arranged as a series of (major or minor) thirds may be called a tertian chord. Most common chords are tertian.

A chord such as C-D-E♭, though, is a series of seconds, containing a major second (C-D) and a minor second (D-E♭). Such chords are called secundal. The chord C-F-B, which consists of a perfect fourth C-F and an augmented fourth (tritone) F-B is called quartal.

However all these terms can become ambiguous when dealing with non-diatonic scales such as the pentatonic or chromatic scales. The use of accidentals can also complicate the terminology. For example the chord B♯-E-A♭ appears to be a series of diminished fourths (B♯-E) and (E-A♭) but is enharmonically equivalent to (and sonically indistinguishable from) the chord C-E-G♯, which is a series of major thirds (C-E) and (E-G♯).

See also Mixed-interval chord.

Triads

Triads, also called triadic chords, are tertian chords (see above) with three notes. The four basic triads are described below.

| Chord name | Component intervals | Example | Chord symbol | Audio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| major triad | major third | perfect fifth | C-E-G | C, CM, Cma, Cmaj, CΔ | |

| minor triad | minor third | perfect fifth | C-E♭-G | Cm, Cmi, Cmin, C- | |

| augmented triad | major third | augmented fifth | C-E-G♯ | C+, C+, Caug | |

| diminished triad | minor third | diminished fifth | C-E♭-G♭ | Cm(♭5), Cº, Cdim, C⌀ | |

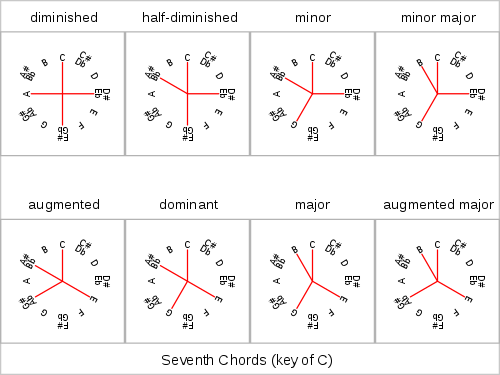

Seventh chords

Seventh chords are tertian chords (see above), constructed by adding a fourth note to a triad, at the interval of a third above the fifth of the chord. This creates the interval of a seventh above the root of the chord, the next natural step in composing tertian chords. The seventh chord on the fifth step of the scale (the dominant seventh) is the only one available in the major scale: it contains all three notes of the diminished triad of the seventh and is frequently used as a stronger substitute for it.

There are various types of seventh chords depending on the quality of both the chord and the seventh added. In chord notation the chord type is sometimes superscripted and sometimes not (e.g. Dm7, Dm7, and Dm7 are all identical).

| Chord name | Component notes (intervals) | Chord symbol | Example (C root) | Audio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| diminished seventh | minor third | diminished fifth | diminished seventh | Co7, Cdim7 | C E♭ G♭ B |

|

| half-diminished seventh | minor third | diminished fifth | minor seventh | Cø7, Cm7♭5, C-7(♭5) | C E♭ G♭ B♭ | |

| minor seventh | minor third | perfect fifth | minor seventh | Cm7, C−7, C−7 | C E♭ G B♭ | |

| minor major seventh | minor third | perfect fifth | major seventh | Cm(Maj7), C−(j7), Cm♯7, C−Δ7, C−maj7 | C E♭ G B | |

| Dominant seventh chord | major third | perfect fifth | minor seventh | C7, C7, Cdom7 | C E G B♭ | |

| Major seventh chord | major third | perfect fifth | major seventh | CMaj7, CM7, CΔ7, Cj7, C+7 | C E G B | |

| augmented seventh | major third | augmented fifth | minor seventh | C+7, C7+, C7+5, C7♯5 | C E G♯ B♭ | |

| augmented major seventh | major third | augmented fifth | major seventh | C+(Maj7), CMaj7+5, CMaj7♯5, C+j7, CΔ+7 | C E G♯ B | |

Extended chords

Extended chords are triads with further tertian notes added beyond the seventh; the ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth chords. After the thirteenth any notes added in thirds will duplicate notes elsewhere in the chord: all seven notes of the scale are present in the chord and further added notes will not give new pitch classes. Such chords may be constructed only by using notes that lie outside the diatonic seven-note scale (See #Altered chords below).

| Chord name | Component notes (chord and interval) | Chord symbol | Audio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dominant ninth | dominant seventh chord | major ninth | - | - | C9 | |

| Dominant eleventh | dominant seventh the third is usually omitted |

major ninth | perfect eleventh | - | C11 | |

| Dominant thirteenth | dominant seventh the eleventh is usually omitted |

major ninth | perfect eleventh | major thirteenth | C13 | |

Other extended chords follow the same rules as shown above, so that for example Maj9, Maj11 and Maj13, shown above are with major sevenths rather than minor sevenths: similarly m9, m11 and m13 will have minor thirds and minor sevenths.

Altered chords

Although the third and seventh of the chord are always determined by the symbols shown above, the fifth, ninth, eleventh and thirteenth may all be chromatically altered by accidentals (the root cannot be so altered without changing the name of the chord, while the third cannot be altered without altering the chord's quality). These are noted alongside the element to be altered. Accidentals are most often used in conjunction with dominant seventh chords. "Altered" dominant seventh chords (C7alt) may have a flat ninth, a sharp ninth, a diminished fifth or an augmented fifth (see Levine's Jazz Theory). Some write this as C7+9, which assumes also the flat ninth, diminished fifth and augmented fifth (see Aebersold's Scale Syllabus). The augmented ninth is often referred to in blues and jazz as a blue note, being enharmonically equivalent to the flat third or tenth. When superscripted numerals are used the different numbers may be listed horizontally (as shown) or else vertically.

| Chord name | Component notes | Chord symbol | Audio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seventh augmented fifth | dominant seventh | augmented fifth | C7+5, C7♯5 | |

| Seventh flat nine | dominant seventh | minor ninth | C7-9, C7♭9 | |

| Seventh sharp nine | dominant seventh | augmented ninth | C7+9, C7♯9 | |

| Seventh augmented eleventh | dominant seventh | augmented eleventh | C7+11, C7♯11 | |

| Seventh flat thirteenth | dominant seventh | minor thirteenth | C7-13, C7♭13 | |

| Half-diminished seventh | minor seventh | diminished fifth | Cø, Cm7♭5 | |

Added tone chords

An added tone chord is a triad chord with an added, non-tertian note, such as the commonly added sixth as well as chords with an added second (ninth) or fourth (eleventh) or a combination of the three. These chords do not include "intervening" thirds as in an extended chord. Added chords can also have variations. Thus madd9, m4 and m6 are minor triads with extended notes.

Added-sixth chords can be considered as belonging to either of two separate groups; chords that contain the sixth (from the root) as a chord member—a note separated by the interval of a sixth from the chord's root—and inverted chords in which the interval of a sixth appears above a bass note that is not the root[citation needed].

The major sixth chord (also called, sixth or added sixth with the chord notation 6, e.g., "C6") is by far the most common type of sixth chord of the first group. It comprises a major chord with the added major sixth above the root, common in popular music[2]. For example, the chord C6 contains the notes C-E-G-A. The minor sixth chord (min6 or m6, e.g., "Cm6") is a minor chord with the same added note. For example, the chord Cmin6 contains the notes C-E♭-G-A. In chord notation, the sixth of either chord is always assumed to be a major sixth rather than a minor sixth, however a minor sixth may be indicated in the notation as, for example, "Cm(min6)" or "Cm♭6". The augmented sixth chord usually appears in chord notation as its enharmonic equivalent, the seventh chord. This chord contains two notes separated by the interval of an augmented sixth (or, by inversion, a diminished third, though this inversion is rare). The augmented sixth is generally used as a dissonant interval most commonly used in motion towards a dominant chord in root position (with the root doubled to create the octave to which the augmented sixth chord resolves) or to a tonic chord in second inversion (a tonic triad with the fifth doubled for the same purpose). In this case, the tonic note of the key is included in the chord, sometimes along with an optional fourth note, to create one of the following (illustrated here in the key of C major):

- Italian augmented sixth: A♭, C, F♯

- French augmented sixth: A♭, C, D, F♯

- German augmented sixth: A♭, C, E♭, F♯

The augmented sixth family of chords exhibits certain peculiarities. Since they are not based on triads, as are seventh chords and other sixth chords, they are not generally regarded as having roots (nor, therefore, inversions), although one re-voicing of the notes is common (with the namesake interval inverted to create a diminished third).

The second group of sixth chords includes inverted major and minor chords, which may be called sixth chords in that the six-three (6/3) and six-four (6/4) chords contain intervals of a sixth with the bass note, though this is not the root. Nowadays this is mostly for academic study or analysis (see figured bass) but the neapolitan sixth chord is an important example; a major triad with a flat supertonic scale degree as its root that is called a "sixth" because it is almost always found in first inversion. Though a technically accurate Roman numeral analysis would be ♭II, it is generally labelled N6. In C major, the chord is notated (from root position) D♭, F, A♭. Because it uses chromatically altered tones this chord is often grouped with the borrowed chords (see below) but the chord is not borrowed from the relative major or minor and it may appear in both major and minor keys.

| Chord name | Component notes (chord and interval) | Chord symbol | Audio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Add nine | major triad | major ninth | - | C2, Cadd9 | |

| Major 4th | major triad | perfect fourth | - | C4, Cadd11 | |

| Major sixth | major triad | major sixth | - | C6 | |

| Six-nine | major triad | major sixth | major ninth | C6/9 | |

Suspended chords

A suspended chord, or "sus chord" (sometimes wrongly thought to mean sustained chord), is a chord in which the third is delayed by either of its dissonant neighbouring notes, forming intervals of a major second or (more commonly) a perfect fourth with the root. This results in two distinct chord types: the suspended second (sus2) and the suspended fourth (sus4). The chords, Csus2 and Csus4, for example, consist of the notes C D G and C F G, respectively.

The name suspended derives from an early polyphonic technique developed during the common practice period, in which a stepwise melodic progress to a harmonically stable note in any particular part was often momentarily delayed or suspended by extending the duration of the previous note. The resulting unexpected dissonance could then be all the more satisfyingly resolved by the eventual appearance of the displaced note. In traditional music theory the inclusion of the third in either chord would negate the suspension, so such chords would be called added ninth and added eleventh chords instead.

In modern layman usage the term is restricted to the displacement of the third only and the dissonant second or fourth no longer needs to be held over ("prepared") from the previous chord. Neither is it now obligatory for the displaced note to make an appearance at all though in the majority of cases the conventional stepwise resolution to the third is still observed. In post-bop and modal jazz compositions and improvisations suspended seventh chords are often used in nontraditional ways: these often do not function as V chords, and do not resolve from the fourth to the third. The lack of resolution gives the chord an ambiguous, static quality. Indeed, the third is often played on top of a sus4 chord. A good example is the jazz standard, "Maiden Voyage".

Extended versions are also possible, such as the seventh suspended fourth which, with root C, contains the notes C F G B♭ and is notated as C7sus4 . Csus4 is sometimes written Csus since the sus4 is more common than the sus2.

Notation

Chords can be notated in many and various different ways. The most commonly used notation in Western academic circles is that of Roman numerals, coupled with figured bass notation. Other methods include jazz notation and pop notation but there are many other methods which are not all formalized.

In Western music theory, a chord name (e.g. C major seventh), and the corresponding chord symbol (e.g. CM7), are often composed of three parts:

- The root note (e.g. C)

- The chord quality (e.g. major, or M)

- An interval number (e.g. seventh, or 7)

Chord qualities are related with the qualities of the component intervals which define the chord (see below). The main chord qualities are:

- Major or minor.

- Augmented, diminished, or half-diminished.

- Dominant.

The symbols used for chord quality are similar to those used for interval quality. In addition, however,

- Δ is sometimes used for major, instead of the standard M, or maj

- − is sometimes used for minor, instead of the standard m or min

- +, or aug, or ♯ is used for augmented (A is not used),

- o, °, dim, or ♭ is used for diminished (d is not used),

- ø, or Ø is used for half diminished.

- dom is used for dominant.

Notice that ♯ and ♭ are used only in composite symbols such as C7(♯5), or Cm(♭7), where they are not adjacent to the root, and cannot be interpreted as a sharp or flat accidental.

Only a very limited amount of information is explicitly provided in the chord symbol or chord name. However, it is often necessary to deduce from it the component intervals which define the chord. The missing information is implied and must be deduced according to some rules.

Relationship between chord name or symbol and chord definition

The rules described here apply to most 3-note chords (triads) and 4-note chords (tetrads). There are four main triads (major, minor, augmented, diminished), and they are all tertian, i.e. defined by the root, a third interval, and a fifth interval. Since the main tetrads are obtained by adding one note to these four basic triads, their name and symbol is often built by just adding to the name and symbol of the basic triad the number for the added interval. For instance, a C major seventh chord (CM7) is a C major triad (CM) with an extra major seventh interval (M7). Thus, the quality of the tetrad is often the same as the quality of the basic triad it contains.

Some chord symbols or chord names may not include the interval number, the chord quality, or both (see table below). For instance, C or CM is typically used instead of CM3 (major triad). Even when root, quality, and number are all included (e.g. in CM7), the quality of the added interval is not specified, and must be deduced.

1) General rule to interpret the existing information

- For triads, the symbols for major or minor (e.g. M, or m) always refer to the third interval, while those for augmented and diminished (e.g. + or o) always refer to the fifth. Thus, the 3 for the third, and the 5 for the fifth are typically omitted.

- This rule can be generalized, as it always holds for tetrads as well, provided the above mentioned symbols appear immediately after the root note. For instance, in the chord symbols CM and CM7, M refers to the interval M3. On the other hand, in Cm/M7 (minor-major seventh chord), M refers only to the M7 interval, as it does not appear immediately after the root note C.

2) General rule to deduce missing information

- Without contrary information, a major third interval and a perfect fifth interval (major triad) are implied. For instance, a C chord is a C major triad (both the major third and the perfect fifth are implied).

- Rules 1 and 2 can be easily combined. For instance, both in Cm (C minor triad), and in Cm7 (C minor seventh chord) a minor third is deduced according to rules 1 and 2, and a perfect fifth is implied according to rule 3.

3) Specific rules to deduce missing information

- A plain 6 stands for M6, a chord formed by a major sixth interval, added to the implied major triad.

- A plain 7 stands for dom7, a chord formed by a minor seventh interval, added to the implied major triad.

- For sixth chord names or symbols composed only of root, quality and number (such as "C major sixth", or "CM6"):

- M, maj, or major stands for major-major (e.g. CM6 means CM/M6, or CM3/M6),

- m, min, or minor stands for minor-major (e.g. Cm7 means Cm/M7, or Cm3/M7).

- For seventh chord names or symbols composed only of root, quality and number (such as "C major seventh", or "CM7"):

- M, maj, or major stands for major-major (e.g. CM7 means CM/M7, or CM3/M7),

- m, min, or minor stands for minor-minor (e.g. Cm7 means Cm/m7, or Cm3/m7),

- +, aug, or augmented stands for augmented-minor (e.g. C+7 means C+/m7, or C+5/m7),

- o, dim, or diminished stands for diminished-diminished (e.g. Co7 means Co/o7, or Co5/o7),

- ø, or half-diminished stands for diminished-minor (e.g. Cø7 means Co/m7, or Co5/m7).

Examples

- The table shows the application of these generic and specific rules to interpret some of the main chord symbols. The same rules apply for the analysis of chord names. Only a very limited amount of information is explicitly provided in the chord symbol (boldface font in the column labeled "Component intervals"), and can be easily interpreted with rule 1. The rest is implied (plain font), and can be deduced by applying the other rules. The "Analysis of symbol parts" is performed by applying rule 1.

Chord Symbol Analysis of symbol parts Component intervals Chord name Short Other Rarely used Root Third Fifth Added Third Fifth Added C C maj3 perf5 Major triad CM Cmaj CM3 or Cmaj3 C maj maj3 perf5 Cm Cmin Cm3 or Cmin3 C min min3 perf5 Minor triad C+ Caug C+5 or Caug5 C aug maj3 aug5 Augmented triad Co Cdim Co5 or Cdim5 C dim min3 dim5 Diminished triad C6 C 6 maj3 perf5 maj6 Major sixth chord CM6 C maj 6 maj3 perf5 maj6 Cm6 C min 6 min3 perf5 maj6 Minor sixth chord C7 Cdom7 C 7 maj3 perf5 min7 Dominant seventh chord CM7 Cmaj7 C maj 7 maj3 perf5 maj7 Major seventh chord Cm7 Cmin7 C min 7 min3 perf5 min7 Minor seventh chord C+7 Caug7 C aug 7 maj3 aug5 min7 Augmented seventh chord Co7 Cdim7 C dim 7 min3 dim5 dim7 Diminished seventh chord Cø7 C dim 7 min3 dim5 min7 Half-diminished seventh chord Cm/M7 Cmin/maj7 Cmin3/maj7 C min 7 min3 perf5 maj7 Minor-major seventh chord Cm(M7) Cmin(maj7) Cmin3(maj7)

Borrowed chords

A borrowed chord is one that is taken from a different key to that of the piece it is used in. The most common occurrence of this is where a chord from the parallel major or minor is used, with particularly good examples of this evident through-out the works of composers such as Schubert. Indeed it was Schubert (and although later Schenker) who first hypothesized that tonal areas should be based around a note rather than a particular mode such as major[citation needed]. This approach can be seen in works of Schubert's such as Winterreise. When a tonal area include both the major and minor modes it leads to the free use of chords from either major or minor in any one key area. If a composer is working in C major they would be borrowing a chord if they used a major ♭III chord as this appears in C minor only.

Although borrowed chords could theoretically include chords taken from any key other than the home key this is not how the term is used when a chord is described in formal musical analysis.

Progression

Whenever different chords are played in sequence they can be described as a progression. The relative importance of each chord within a progression is taken from its situation both metrically and harmonically relative to the tonal centre.

- According to Goldman (1965, p. 26);

"the sense of harmonic relation, change, or effect depends on speed (or tempo) as well as on the relative duration of single notes or triadic units. Both absolute time (measurable length and speed) and relative time (proportion and division) must at all times be taken into account in harmonic thinking or analysis."

Chords which are particularly dissonant with relation to the home key create tension and chords close to the home key lessen tension. If a chord falls on the strong beat of a bar (commonly beat 1 or 3 in common time) then it is highlighted and its dissonance (or lack of) is attenuated. The picture is an example of a chord progression ending on the tonal centre which is highlighted by its metric position. Interestingly the dominant chord proceeding it, a structurally dissonant chord, falls on the weakest beat of the bar. The general function of the use of chord progressions is to support a melody and add both interest and direction (through dissonance and resolution) which would not otherwise be inherent in the melody.

See also

- Chord bible

- Elektra chord

- Chord factor

- Guitar chord

- Harmonized scale

- Homophony

- Mystic chord

- Open chord

- Petrushka chord

- Prolongation

- Psalms chord

- Spider chord

- Subsidiary chord

References

- ^ Arnold Schoenberg, Structural Functions of Harmony, Faber and Faber, 1983, p.1-2.

- ^ a b Benward & Saker (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I, p. 77. Seventh Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- ^ Schellenberg, E. Glenn; Bigand, Emmanuel; Poulin-Charronnat, Benedicte; Garnier, Cecilia; Stevens, Catherine (Nov.). "Children's implicit knowledge of harmony in Western music". Developmental Science. 8 (8): 551–566. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.00447.x. PMID 16246247.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ Károlyi, Otto, Introducing Music, p. 63. England: Penguin Books.

- Grout, Donald Jay (1960). A History Of Western Music. Norton Publishing.

- Dahlhaus, Carl. Gjerdingen, Robert O. trans. (1990). Studies in the Origin of Harmonic Tonality, p. 67. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09135-8.

- Goldman (1965). Cited in Nattiez (1990).

- Jones, George T. (1994). HarperCollins College Outline Music Theory. ISBN 0-06-467168-2.

- Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1990). Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music (Musicologie générale et sémiologue, 1987). Translated by Carolyn Abbate (1990). ISBN 0-691-02714-5.

- Norman Monath, Norman (1984). How To Play Popular Piano In 10 Easy Lessons. Fireside Books. ISBN 0-671-53067-4.

- Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell, eds. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. ISBN 1-56159-239-0.

- Surmani, Andrew (2004). Essentials of Music Theory: A Complete Self-Study Course for All Musicians. ISBN 0-7390-3635-1.

Further reading

- Schejtman, Rod (2008). Music Fundamentals. The Piano Encyclopedia. ISBN 978-987-25216-2-2.

- Persichetti, Vincent (1961). Twentieth-century Harmony: Creative Aspects and Practice. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-09539-8. OCLC 398434.

- Benward, Bruce & Saker, Marilyn (2002). Music in Theory and Practice, Volumes I & II (7th ed.). New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-07-294262-2.

- Piston, Walter (1987). Harmony (5th ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-95480-3.

External links

- Piano Chord Dictionary Online browser able to show any chord (and inversion) as played on the piano.

- Music Fundamentals eBook An eBook that explains how to build any chord by using music intervals. Available for free.

- Morphogenesis of chords and scales Chords and scales classification

- Chord Identifier Online tool for searching chords that have a specific set of notes (useful for fitting chords to a scale, melody or riff).

- Decoding the Circle of Vths Advanced online tool for analyzing and searching structures and substructures over the circle of Vths.