The King and I: Difference between revisions

→Inception: one revision to fine edits, "focused in" implies a conscious choice, which may be too strong |

m →Film and television versions: punct. See previous edit summary. |

||

| (25 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''''The King and I''''' is a 1951 [[musical theatre|stage musical]], the fifth by the team of [[Richard Rodgers]] and [[Oscar Hammerstein II]]. The play is based on the 1944 novel ''[[Anna and the King of Siam (book)|Anna and the King of Siam]]'' by [[Margaret Landon]] and derives from the memoirs of [[Anna Leonowens]], who became governess to the children of [[Mongkut|King Mongkut]] of [[Thailand|Siam]] in the early 1860s. The |

'''''The King and I''''' is a 1951 [[musical theatre|stage musical]], the fifth by the team of [[Richard Rodgers]] and [[Oscar Hammerstein II]]. The play is based on the 1944 novel ''[[Anna and the King of Siam (book)|Anna and the King of Siam]]'' by [[Margaret Landon]] and derives from the memoirs of [[Anna Leonowens]], who became governess to the children of [[Mongkut|King Mongkut]] of [[Thailand|Siam]] in the early 1860s. The story deals with the experiences of the British schoolteacher, who is hired as part of the King's drive to modernize his country. Anna and the King struggle to come to a mutual understanding despite their contrasting cultural backgrounds. She also assists Tuptim, one of the King's slaves, who wishes to escape from the court with the man she loves. |

||

In 1950, theatrical attorney [[Fanny Holtzmann]] was looking for a part for her client, Broadway and London legend [[Gertrude Lawrence]]. Holtzmann realized that Landon's book would be an ideal vehicle and contacted [[Rodgers and Hammerstein]], who were initially reluctant, but agreed to write the musical. The pair initially sought [[Rex Harrison]] to play the supporting part of the King—he had played the role in [[Anna and the King of Siam (film)|the 1946 movie]] made from Landon's book—but Harrison was unavailable. They settled on Russian-American actor [[Yul Brynner]]. |

In 1950, theatrical attorney [[Fanny Holtzmann]] was looking for a part for her client, Broadway and London legend [[Gertrude Lawrence]]. Holtzmann realized that Landon's book would be an ideal vehicle and contacted [[Rodgers and Hammerstein]], who were initially reluctant, but agreed to write the musical. The pair initially sought [[Rex Harrison]] to play the supporting part of the King—he had played the role in [[Anna and the King of Siam (film)|the 1946 movie]] made from Landon's book—but Harrison was unavailable. They settled on Russian-American actor [[Yul Brynner]]. |

||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

Both men had to overcome problems with how to properly represent Siamese speech or music. Rodgers did not wish to use actual Siamese music, which the audience might not like. Instead, he gave his music an exotic tone while avoiding actual Asian melodies.<ref name = "f293"/> Rodgers had experimented with music for an Asian setting in his short-lived 1928 musical with [[Lorenz Hart]], ''Chee-chee''.<ref name = "s311">Secrest, p. 311</ref> Hammerstein needed to decide how to represent Siamese-language speech. He heard actual Siamese speech while in London for the production of ''[[Carousel (musical)|Carousel]]'', and it sounded almost musical to him. He decided that when the characters were to speak in Siamese, that speech would be conveyed by musical sounds, made by the orchestra. For the speech of the King, Hammerstein developed an abrupt, emphatic way of talking, which was free of articles, as are many Oriental languages. The forcefulness of the King's speech reflected his personality.<ref name = "f293">Fordin, p. 293</ref> The manner of speech was maintained even when the King sang, especially in his one solo number, "A Puzzlement".<ref>Fordin, p. 294</ref> With Rodgers laid up with back trouble, Hammerstein completed most of the book before many songs were set to music.<ref>Fordin, p. 295</ref> |

Both men had to overcome problems with how to properly represent Siamese speech or music. Rodgers did not wish to use actual Siamese music, which the audience might not like. Instead, he gave his music an exotic tone while avoiding actual Asian melodies.<ref name = "f293"/> Rodgers had experimented with music for an Asian setting in his short-lived 1928 musical with [[Lorenz Hart]], ''Chee-chee''.<ref name = "s311">Secrest, p. 311</ref> Hammerstein needed to decide how to represent Siamese-language speech. He heard actual Siamese speech while in London for the production of ''[[Carousel (musical)|Carousel]]'', and it sounded almost musical to him. He decided that when the characters were to speak in Siamese, that speech would be conveyed by musical sounds, made by the orchestra. For the speech of the King, Hammerstein developed an abrupt, emphatic way of talking, which was free of articles, as are many Oriental languages. The forcefulness of the King's speech reflected his personality.<ref name = "f293">Fordin, p. 293</ref> The manner of speech was maintained even when the King sang, especially in his one solo number, "A Puzzlement".<ref>Fordin, p. 294</ref> With Rodgers laid up with back trouble, Hammerstein completed most of the book before many songs were set to music.<ref>Fordin, p. 295</ref> |

||

Hammerstein immediately contacted set designer [[Jo Mielziner]] and costume designer [[Irene Sharaff]] and asked them to begin work in coordination with each other. Sharaff communicated with [[Jim Thompson (designer)|Jim Thompson]], an American who had revived the Thai silk industry after [[World War II]]. Thompson sent Sharaff samples of silk cloth from Thailand and pictures of local dress from the mid-19th century.<ref>Fordin, pp. 292–93</ref> One such picture, of a Thai woman in western dress, inspired the song "Western People Funny", sung by the King's chief wife, Lady Thiang, while dressed in western garb.<ref name = "f296">Fordin, p. 296</ref> Producer [[Leland Hayward]], who had worked with the duo on ''South Pacific'', approached choreographer [[Jerome Robbins]] to arrange "The Small House of Uncle Thomas". Robbins was very enthusiastic about the project, and asked to choreograph the other musical numbers as well, which Rodgers and Hammerstein had thought unnecessary, as no other significant dancing was planned. Once hired, Robbins arranged "The Small House of Uncle Thomas" as an intimate performance, rather than a large production number.<ref name = "f296"/> His choreography for the parade of the King's children to meet their teacher ("March of the Royal Siamese Children") drew great acclaim.<ref name = "n208">Nolan, p. 208</ref> |

Hammerstein immediately contacted set designer [[Jo Mielziner]] and costume designer [[Irene Sharaff]] and asked them to begin work in coordination with each other. Sharaff communicated with [[Jim Thompson (designer)|Jim Thompson]], an American who had revived the Thai silk industry after [[World War II]]. Thompson sent Sharaff samples of silk cloth from Thailand and pictures of local dress from the mid-19th century.<ref>Fordin, pp. 292–93</ref> One such picture, of a Thai woman in western dress, inspired the song "Western People Funny", sung by the King's chief wife, Lady Thiang, while dressed in western garb.<ref name = "f296">Fordin, p. 296</ref> Producer [[Leland Hayward]], who had worked with the duo on ''South Pacific'', approached choreographer [[Jerome Robbins]] to arrange "The Small House of Uncle Thomas". Robbins was very enthusiastic about the project, and asked to choreograph the other musical numbers as well, which Rodgers and Hammerstein had thought unnecessary, as no other significant dancing was planned. Once hired, Robbins arranged "The Small House of Uncle Thomas" as an intimate performance, rather than a large production number.<ref name = "f296"/> His choreography for the parade of the King's children to meet their teacher ("March of the Royal Siamese Children") drew great acclaim.<ref name = "n208">Nolan, p. 208</ref> [[Robert Russell Bennett]] provided the orchestrations, and [[Trude Rittman]] arranged the ballet music.<!-- Lots of web sources confirm this, but one of your books must say so. --> |

||

The pair had contemplated an Act 1 musical scene involving Anna and the King's wives. The song to put in that scene proved to be very difficult to write for Hammerstein. He felt Anna would tell the wives something about her past, and wrote such lyrics as "I was dazzled by the splendor/Of Calcutta and Bombay" and "The celebrities were many/And the parties very gay/(I recall a curry dinner/And a certain Major Grey)."<ref name = "lyric"/> Eventually, Hammerstein decided to write about how Anna felt, a song which would, in addition to explaining her past, serve as a bond with Tuptim and lay the groundwork for the conflict which eventually devastates her relationship with the King.<ref name = "lyric">Mordden, p. 144</ref> "Hello, Young Lovers", the resultant song, was the work of five exhausting weeks for Hammerstein. He finally sent the lyric to Rodgers by messenger and awaited his reaction. No word came. Hammerstein considered the song his best work, and was anxious to hear what Rodgers thought of it, but still no comment came from Rodgers. Pride kept Hammerstein from asking. Finally, after four days, the two happened to be talking on the phone about other matters, and at the end of the conversation, Rodgers stated, very briefly, that the lyric was fine. Josh Logan found the usually unflappable Hammerstein extremely upset, and the lyricist poured out his feelings to Logan, before suddenly stopping, one of the few times that Hammerstein and Rodgers did not display a united front.<ref name = "f299">Fordin, p. 299</ref> |

The pair had contemplated an Act 1 musical scene involving Anna and the King's wives. The song to put in that scene proved to be very difficult to write for Hammerstein. He felt Anna would tell the wives something about her past, and wrote such lyrics as "I was dazzled by the splendor/Of Calcutta and Bombay" and "The celebrities were many/And the parties very gay/(I recall a curry dinner/And a certain Major Grey)."<ref name = "lyric"/> Eventually, Hammerstein decided to write about how Anna felt, a song which would, in addition to explaining her past, serve as a bond with Tuptim and lay the groundwork for the conflict which eventually devastates her relationship with the King.<ref name = "lyric">Mordden, p. 144</ref> "Hello, Young Lovers", the resultant song, was the work of five exhausting weeks for Hammerstein. He finally sent the lyric to Rodgers by messenger and awaited his reaction. No word came. Hammerstein considered the song his best work, and was anxious to hear what Rodgers thought of it, but still no comment came from Rodgers. Pride kept Hammerstein from asking. Finally, after four days, the two happened to be talking on the phone about other matters, and at the end of the conversation, Rodgers stated, very briefly, that the lyric was fine. Josh Logan found the usually unflappable Hammerstein extremely upset, and the lyricist poured out his feelings to Logan, before suddenly stopping, one of the few times that Hammerstein and Rodgers did not display a united front.<ref name = "f299">Fordin, p. 299</ref> |

||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

==Casting and tryouts== |

==Casting and tryouts== |

||

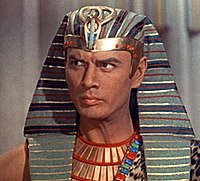

[[File:Yul Brynner in The Ten Commandments film trailer.jpg|thumb|right|200px|[[Yul Brynner]], in costume in ''[[The Ten Commandments (film)|The Ten Commandments]]'']] |

[[File:Yul Brynner in The Ten Commandments film trailer.jpg|thumb|right|200px|[[Yul Brynner]], in costume in ''[[The Ten Commandments (film)|The Ten Commandments]]'']] |

||

Although the part of the King was only a supporting role to Lawrence's Anna |

Although the part of the King was only a supporting role to Lawrence's Anna, Hammerstein and Rodgers thought it essential that a well-known theatrical actor play the role. The obvious choice was Rex Harrison, who had played the King in the movie, but he was booked, as was [[Noël Coward]]. [[Alfred Drake]], the original Curly in ''[[Oklahoma!]]'', made contractual demands which were too high. With time running short before rehearsals, finding an actor to find the King became a major concern. [[Mary Martin]], the original Nellie Forbush in ''[[South Pacific]]'' suggested that her co-star in a 1946 production of ''[[Lute Song (musical)|Lute Song]]'' try for the role.<ref>Hammerstein, pp. 204–05</ref> Rodgers later recalled the audition of the Russian-American performer, [[Yul Brynner]]: |

||

<blockquote> |

<blockquote> |

||

They told us the name of the first man and out he came with a bald head and sat cross-legged on the stage. He had a guitar and he hit his guitar one whack and gave out with this unearthly yell and sang some heathenish sort of thing, and Oscar and I looked at each other and said, "Well, that's it."<ref>Nolan, p. 202</ref> |

They told us the name of the first man and out he came with a bald head and sat cross-legged on the stage. He had a guitar and he hit his guitar one whack and gave out with this unearthly yell and sang some heathenish sort of thing, and Oscar and I looked at each other and said, "Well, that's it."<ref>Nolan, p. 202</ref> |

||

</blockquote> |

</blockquote> |

||

Brynner, however, later termed Rodgers's account "very picturesque, but totally inaccurate". He related that as an established television director, he was reluctant to go back on the stage. Mary Martin, his wife and his agent finally convinced him to read Hammerstein's working script, and once he did, he was fascinated by the character of the King and was eager to do the project.<ref>Nolan, pp. |

Brynner, however, later termed Rodgers's account "very picturesque, but totally inaccurate". He related that as an established television director, he was reluctant to go back on the stage. Mary Martin, his wife and his agent finally convinced him to read Hammerstein's working script, and once he did, he was fascinated by the character of the King and was eager to do the project.<ref>Nolan, pp. 202–03</ref> |

||

Pre-rehearsal preparations began in the autumn of 1950. Hammerstein had wanted [[Joshua Logan]] to direct and co-write the book, but when Logan declined Hammerstein decided to write the book himself. Instead of Logan, the duo hired [[John van Druten]], who had worked with Lawrence years earlier, to direct. Sharaff was quoted as saying, "The first-act finale of ''The King and I'' will feature Miss Lawrence, Mr. Brynner, and a pink satin ball gown."<ref>Hammerstein, p. 206</ref> Mielziner's set plan was the simplest of the four Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals he had worked on, with one main set (the throne room), a number of front-stage drops (for the ship and Anna's room, for example) and the entire stage cleared for "The Small House of Uncle Thomas".<ref>Mordden, p. 137</ref> |

Pre-rehearsal preparations began in the autumn of 1950. Hammerstein had wanted [[Joshua Logan]] to direct and co-write the book, but when Logan declined, Hammerstein decided to write the book himself. Instead of Logan, the duo hired [[John van Druten]], who had worked with Lawrence years earlier, to direct. Sharaff was quoted as saying, "The first-act finale of ''The King and I'' will feature Miss Lawrence, Mr. Brynner, and a pink satin ball gown."<ref>Hammerstein, p. 206</ref> Mielziner's set plan was the simplest of the four Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals he had worked on, with one main set (the throne room), a number of front-stage drops (for the ship and Anna's room, for example) and the entire stage cleared for "The Small House of Uncle Thomas".<ref>Mordden, p. 137</ref> |

||

The show was budgeted at $250,000, making it the most expensive Rodgers and Hammerstein production to that point, and prompting some mocking that it |

The show was budgeted at $250,000, making it the most expensive Rodgers and Hammerstein production to that point, and prompting some mocking that it exceeded even their expensive flop ''[[Allegro]]''.<ref>Nolan, p. 204</ref> Additional investors included Josh Logan, Mary Martin, [[Billy Rose]] and [[Leland Hayward]].<ref name = "m190"/> The children who were cast as the young princes and princesses, were from a wide range of ethnic backgrounds, though none were Thai. Some of the young performers who were hired during the show's run were Puerto Rican or Italian.<ref>Capua, p. 38</ref> |

||

Shortly before rehearsals began in January 1951, Rodgers had the first Tuptim, [[Doretta Morrow]] sing the entire score to Lawrence, including Lawrence's own songs. Lawrence listened calmly, but when meeting Rodgers and Hammerstein the following day, greeted the lyricist warmly, but cut Rodgers dead, apparently seeing the composer's actions as flaunting her vocal deficiencies.<ref>Hyland, p. 200</ref> Early in rehearsals, Lawrence realized the score was more complex than any she had sung in the past, and she feared she had taken on more than she could manage. Rodgers had composed her songs with her limited vocal range in mind, but she remained on edge and difficult to handle.<ref name = "m190">Morley, p. 190</ref> One reason that the team had sought Coward as the King was in the belief that Coward could handle Lawrence—director van Druten proved incapable of the task. Much of the work of |

Shortly before rehearsals began in January 1951, Rodgers had the first Tuptim, [[Doretta Morrow]], sing the entire score to Lawrence, including Lawrence's own songs. Lawrence listened calmly, but when meeting Rodgers and Hammerstein the following day, greeted the lyricist warmly, but cut Rodgers dead, apparently seeing the composer's actions as flaunting her vocal deficiencies.<ref>Hyland, p. 200</ref> Early in rehearsals, Lawrence realized the score was more complex than any she had sung in the past, and she feared she had taken on more than she could manage. Rodgers had composed her songs with her limited vocal range in mind, but she remained on edge and difficult to handle.<ref name = "m190">Morley, p. 190</ref> One reason that the team had sought Coward as the King was in the belief that Coward could handle Lawrence—director van Druten proved incapable of the task. Much of the work of calming Lawrence fell to Brynner, and in recognition of this, Lawrence asked, shortly before her death, that he be given star billing, "He's earned it."<ref>Nolan, p. 203</ref> Nevertheless, Hammerstein and Rodgers's doubts about whether Lawrence could handle the part were assuaged by the sheer force of her acting. James Poling, a writer for ''[[Collier's]]'' who was allowed to attend the rehearsals, wrote of Lawrence rehearsing "Shall I Tell You What I Think of You?": |

||

<blockquote> |

<blockquote> |

||

She took the center of the barren stage wearing, for practice, a dirty muslin hoop over her slacks, with an old jacket thrown on for warmth. She began rather quietly on the note, "Your servant! Your servant! Indeed I'm not your servant!" Then she gradually built the scene, slowly but powerfully, until, in a great crescendo, she ended prone on the floor, pounding in fury, and screaming, "Toads! Toads! Toads! All of your people are toads." When she finished, the handful of professionals in the theatre burst into admiring applause.<ref name = "s311"/> |

She took the center of the barren stage wearing, for practice, a dirty muslin hoop over her slacks, with an old jacket thrown on for warmth. She began rather quietly on the note, "Your servant! Your servant! Indeed I'm not your servant!" Then she gradually built the scene, slowly but powerfully, until, in a great crescendo, she ended prone on the floor, pounding in fury, and screaming, "Toads! Toads! Toads! All of your people are toads." When she finished, the handful of professionals in the theatre burst into admiring applause.<ref name = "s311"/> |

||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

At his first meeting with Sharaff, Brynner, who had only a fringe of hair, asked what he was to do about it. When told he was to shave it, Brynner was horror-struck and refused, convinced he would look terrible. He finally gave in during tryouts, and put dark makeup on his shaved head. The effect was so well-received that it became Brynner's trademark.<ref>Fordin, p. 297</ref> |

At his first meeting with Sharaff, Brynner, who had only a fringe of hair, asked what he was to do about it. When told he was to shave it, Brynner was horror-struck and refused, convinced he would look terrible. He finally gave in during tryouts, and put dark makeup on his shaved head. The effect was so well-received that it became Brynner's trademark.<ref>Fordin, p. 297</ref> |

||

Lawrence's health caused her to miss several rehearsals, though no one seemed certain what was wrong with her.<ref>Hyland, p. 200</ref> When tryouts opened in [[New Haven, Connecticut]] on February 27, 1951, the show was nearly four hours long. Lawrence, suffering from [[laryngitis]], had missed the [[dress rehearsal]], but managed to make it through the first public performance. The ''[[Variety (magazine)|Variety]]'' critic noted that despite her recent illness she "slinks, acts, cavorts, and in general exhibits exceedingly well her several facets for entertaining", but the ''[[Philadelphia Bulletin]]'' review observed her "already thin voice is now starting to wear a great deal thinner".<ref>Morley, p. 191</ref> Leland Hayward came to see the show in New Haven |

Lawrence's health caused her to miss several rehearsals, though no one seemed certain what was wrong with her.<ref>Hyland, p. 200</ref> When tryouts opened in [[New Haven, Connecticut]] on February 27, 1951, the show was nearly four hours long. Lawrence, suffering from [[laryngitis]], had missed the [[dress rehearsal]], but managed to make it through the first public performance. The ''[[Variety (magazine)|Variety]]'' critic noted that despite her recent illness she "slinks, acts, cavorts, and in general exhibits exceedingly well her several facets for entertaining", but the ''[[Philadelphia Bulletin]]'' review observed her "already thin voice is now starting to wear a great deal thinner".<ref>Morley, p. 191</ref> Leland Hayward came to see the show in New Haven and shocked Rodgers by advising him to close it before it went any further. Rodgers did not take Hayward's advice, but the show left New Haven for Boston at least 45 minutes too long.<ref name = "n207">Nolan, p. 207</ref> [[Gemze de Lappe]], who was one of the dancers, recalled one scene that she regretted was cut: |

||

[[Gemze de Lappe]], who was one of the dancers, recalled one scene that she regretted was cut: |

|||

<blockquote> |

<blockquote> |

||

They took out a wonderful scene. Mrs. Anna's first entrance into the palace comes with a song in which she sings, "Over half a year I have been waiting, waiting, waiting, waiting, waiting, waiting outside your door." At the end she points her umbrella at him, or something like that, and the King says "Off with her head" or words to that effect, and the eunuchs pick her up and carry her off. The King says "Who, who, who?" with great satisfaction, and finds out that he has just thrown out the English schoolteacher. So he says, "Bring her back!" and she is ushered in ... we all loved it.<ref>Secrest, p. 312</ref> |

They took out a wonderful scene. Mrs. Anna's first entrance into the palace comes with a song in which she sings, "Over half a year I have been waiting, waiting, waiting, waiting, waiting, waiting outside your door." At the end she points her umbrella at him, or something like that, and the King says "Off with her head" or words to that effect, and the eunuchs pick her up and carry her off. The King says "Who, who, who?" with great satisfaction, and finds out that he has just thrown out the English schoolteacher. So he says, "Bring her back!" and she is ushered in ... we all loved it.<ref>Secrest, p. 312</ref> |

||

</blockquote> |

</blockquote> |

||

The cut song, "Waiting", was a trio for Anna, the King, and the Kralahome. The Kralahome also lost his only solo, "Who Can Refuse?" Left without a note to sing, Mervyn Vye abandoned the show and was replaced by John Juliano. A song for Lady Thiang, "Now You Leave" was also cut.<ref name = "n207"/> |

The cut song, "Waiting", was a trio for Anna, the King, and the Kralahome. The Kralahome also lost his only solo, "Who Can Refuse?" Left without a note to sing, Mervyn Vye abandoned the show and was replaced by John Juliano. A song for Lady Thiang, "Now You Leave" was also cut.<ref name = "n207"/> After the cuts, the duo felt that the first act was lacking something. Lawrence suggested that they write a song for her and the children. Mary Martin reminded them of a song that had been used in rehearsal in ''South Pacific'' for the show-within-a-show, "Suddenly Lucky". The song had been replaced by "Honey Bun" in ''South Pacific''; its melody served for "Getting to Know You". "Western People Funny" and "I Have Dreamed" were also added in Boston.<ref name = "n208">Nolan, p. 208. Mordden points out (p. 138) that Martin was still engaged in ''South Pacific'' in New York, making it unlikely she would have been in Boston during the tryouts. However, he notes that the episode appears in Martin's autobiography. In some references, "Suddenly Lucky" is called "Suddenly Lovely".</ref> |

||

==Plot== |

==Plot== |

||

===Act 1=== |

===Act 1=== |

||

In Bangkok, Siam (which would later |

In Bangkok, Siam (which would later be known as Thailand), in 1862 a strong-willed, widowed schoolteacher, Anna Leonowens, arrives at the request of the King of Siam to tutor his many children. Anna's young son, Louis, fears the severe countenance of the King’s “Prime Minister” the Kralahome, but Anna refuses to be intimidated ("I Whistle A Happy Tune"). The Kralahome has come to escort them to the palace, where they are expected to live—a violation of Anna's contract, which calls for them to live in a separate house. She momentarily considers returning to Singapore aboard the vessel that brought them here, but leaves with her son and the Kralahome. |

||

Several weeks pass, during which Anna and Louis are confined to their palace rooms. The King receives a gift from the king of Burma, a lovely slave girl named Tuptim, to be one of his many wives. She has been brought by Lun Tha, here to copy a design for a temple, and the two are |

Several weeks pass, during which Anna and Louis are confined to their palace rooms. The King receives a gift from the king of Burma, a lovely slave girl named Tuptim, to be one of his many wives. She has been brought by Lun Tha, here to copy a design for a temple, and the two are deeply in love. Tuptim, left alone momentarily, proclaims that the King may own her, but he does not own her heart, another man does ("My Lord and Master"). The King gives Anna her first audience with him. The schoolteacher is a part of his plan for the modernization of Siam; he is surprised and impressed when she already knows this. She raises the issue of the house with him, he dismisses her protests and orders her to talk with his wives. They are interested in her, and she recalls her late husband, Tom to them ("Hello, Young Lovers"). The King returns to present her new pupils—Anna is to teach those of his 67 children (by Act 2, the figure will be 77) whose mothers are in favor with the King. They enter in procession (Instrumental: "March of the Royal Siamese Children"). Anna is utterly charmed by the children, and formality breaks down after the ceremony as they crowd around her. |

||

Anna has not given up on the house, and teaches the children proverbs and songs extolling the virtues of the home life, much to the irritation of the King. The King has enough worries on his mind without the battle with the schoolteacher, and wonders why the world has become so complicated |

Anna has not given up on the house, and teaches the children proverbs and songs extolling the virtues of the home life, much to the irritation of the King. The King has enough worries on his mind without the battle with the schoolteacher, and wonders why the world has become so complicated ("A Puzzlement"). In the schoolroom, children and wives are hard at work learning English ("The Royal Bangkok Academy"). With the children surprised by a map which shows how small Siam is compared with the rest of the world, Anna tells them that until recently, Siam was just a spot on the map to her ("[[Getting to Know You]]"). Nevertheless, there is disorder as the Crown Prince, Chulalongkorn, refuses to believe the map, and the King enters a noisy and chaotic schoolroom. On ascertaining the situation, he orders the pupils to believe the teacher. Still irritated, he complains to Anna about all the lessons about "home" she has been teaching. Anna stands her ground and insists on the letter of her contract. When the King is dismissive, she threatens to leave Siam, much to the dismay of wives and children. The King orders her to obey as "my servant"; she repudiates the term. She hurries away, and the King dismisses school. He stands for a moment, uncertain of his actions, then also leaves. Tuptim enters to get a book; Lun Tha, searching for Anna, comes upon her, and they muse on the impossibility of their love ("We Kiss in a Shadow"). |

||

Alone in her room, Anna angrily replays the confrontation in her mind and builds her anger against the King ("Shall I Tell You What I Think of You?"). Lady Thiang, the King's head wife, enters and urges Anna to go to the King, who is greatly troubled by news that he is being portrayed as a barbarian to the British, and that they should take over Siam as a [[protectorate]]. Anna is shocked by the accusations—the King may be a polygamist, but he is no barbarian—but she is reluctant to see him after the confrontation they had. Lady Thiang convinces her that though the King is imperfect, he is deserving of support ("Something Wonderful"). Anna goes to him, and finds him anxious for reconciliation, which she grudgingly agrees to. Forewarned that the King will not bring up the subject himself, Anna asks about the news from abroad. The King tells her of the allegations and a new development: the British are sending an envoy to Bangkok to evaluate the situation. Anna "guesses"—the only guise in which the King will accept advice—that the King will receive the envoy in European style, and that the wives will be dressed in Western fashion. Tuptim has been writing a play based on ''[[Uncle Tom's Cabin]]'', that can be presented to the guests. Fresh news arrives—the British are arriving much sooner than thought. Anna and the wives will have to stay up all night so everything is done on time. The King assembles his family for a Buddhist prayer for the success of the venture, and acknowledges before Buddha that Anna will receive the house she has insisted upon. |

Alone in her room, Anna angrily replays the confrontation in her mind and builds her anger against the King ("Shall I Tell You What I Think of You?"). Lady Thiang, the King's head wife, enters and urges Anna to go to the King, who is greatly troubled by news that he is being portrayed as a barbarian to the British, and that they should take over Siam as a [[protectorate]]. Anna is shocked by the accusations—the King may be a polygamist, but he is no barbarian—but she is reluctant to see him after the confrontation they had. Lady Thiang convinces her that though the King is imperfect, he is deserving of support ("Something Wonderful"). Anna goes to him, and finds him anxious for reconciliation, which she grudgingly agrees to. Forewarned that the King will not bring up the subject himself, Anna asks about the news from abroad. The King tells her of the allegations and a new development: the British are sending an envoy to Bangkok to evaluate the situation. Anna "guesses"—the only guise in which the King will accept advice—that the King will receive the envoy in European style, and that the wives will be dressed in Western fashion. Tuptim has been writing a play based on ''[[Uncle Tom's Cabin]]'', that can be presented to the guests. Fresh news arrives—the British are arriving much sooner than thought. Anna and the wives will have to stay up all night so everything is done on time. The King assembles his family for a Buddhist prayer for the success of the venture, and acknowledges before Buddha that Anna will receive the house she has insisted upon. |

||

===Act 2=== |

===Act 2=== |

||

It is the last moment before the British envoy arrives; the wives are dressed in the European gowns, which they find confining ("Western People Funny") It develops |

It is the last moment before the British envoy arrives; the wives are dressed in the European gowns, which they find confining ("Western People Funny"). It develops that, in the rush to be ready, the question of undergarments has been overlooked, and the wives have practically nothing on underneath their gowns. When the British envoy, Sir Edward Ramsay, arrives and gazes at them through a monocle, they are panicked by the "evil eye" and hike their skirts over their head in their rush to leave. Sir Edward is diplomatic about the incident, and engages in small talk with the King and Anna. When the King is called away, it develops that Sir Edward is an old flame of Anna's, and they dance in remembrance of old times, as Edward urges her to return to British society. The King returns and irritably reminds them that dancing is for after dinner. As final preparations for the play are made, Tuptim steals a moment to meet with Lun Tha. He tells her he has an escape plan, and she should be ready to leave after the play ("I Have Dreamed"). Anna encounters them, and they confide in her ("Hello, Young Lovers", reprise). |

||

The play ("Small House of Uncle Thomas") is presented as a traditional-appearing Siamese dance. Tuptim is the narrator, and dramatizes the evil of King Simon of Legree and the efforts of the slave Eliza to gain her freedom from him. She is saved by Buddha, who, after she has crossed miraculous ice pursued by King Simon, causes the ice to melt, drowning the slaveholding King. |

The play ("Small House of Uncle Thomas") is presented as a traditional-appearing Siamese dance. Tuptim is the narrator, and dramatizes the evil of King Simon of Legree and the efforts of the slave Eliza to gain her freedom from him. She is saved by Buddha, who, after she has crossed miraculous ice pursued by King Simon, causes the ice to melt, drowning the slaveholding King. Tuptim does not mince words in the anti-slavery message; she is glad for King Simon's death or the death of any king who pursues a slave who wishes to join her lover. |

||

After the play, Sir Edward makes it clear that the British threat has receded. The King, however, is distracted: he noticed Tuptim's anti-slavery message |

After the play, Sir Edward makes it clear that the British threat has receded. The King, however, is distracted: he noticed Tuptim's anti-slavery message and intends to make his displeasure known to her. Sir Edward takes his leave, and Anna and the King express their delight at how well the evening went. He presents her with a ring, which she accepts though she is not in the habit of accepting gifts from men. Secret police bring disquieting news; Tuptim is missing. The King realizes Anna knows something of this; she parries his inquiry by asking why he should care about a woman who is just another woman to him. He is delighted; she is at last understanding the Siamese perspective. Anna tries to explain to him the Western way of courtship, and tells him of what it is like for a woman at a formal dance ("Shall We Dance?"). She demonstrates the dance to him, and their dancing is interrupted by the Kralahome. Tuptim has been taken in her escape, she has been returned and a search is on for Lun Tha. The King is determined to question Tuptim, and to punish her, though she denies she and Lun Tha were lovers. Anna tries to dissuade him, and he takes the whip himself to prove the domination of his kingship over her influences. Under her gaze, however, he is unable to swing the whip. He rushes off as news arrive that Lun Tha has been found dead, and Tuptim is dragged off swearing to join him in death. Anna returns the ring to the Kralahome as both express their wish that Anna had never come to Siam. |

||

Several months pass. Anna is packed and ready to leave Siam. As she prepares to go to the ship, Chulalongkorn arrives with a letter from the King, who has been unable to resolve the conflicts in himself and is now dying. Anna hurries to his bedside. With the King's approaching death, all is forgiven, and the King prevails on her to accept the ring. He finally persuades her to stay to assist the next king, Chulalongkorn. The King tells Anna to take dictation from the prince, and tells the boy to give orders as if he were King. The boy orders the end of the custom of [[kowtow]]ing, which Anna has greatly disliked. The King does not agree with the decision, but accepts it, hinting to his son that he must maintain a custom of showing respect for the king. As Chulalongkorn continues, prescribing a less arduous bow to show respect for the king, his father quietly dies. At first, this is only noticed by the Kralahome, but Anna notices as well, and kneels by the late King, holding his hand and kissing it. Wives and children bow or curtsey, a gesture of respect to old king and new |

Several months pass. Anna is packed and ready to leave Siam. As she prepares to go to the ship, Chulalongkorn arrives with a letter from the King, who has been unable to resolve the conflicts in himself and is now dying. Anna hurries to his bedside. With the King's approaching death, all is forgiven, and the King prevails on her to accept the ring. He finally persuades her to stay to assist the next king, Chulalongkorn. The King tells Anna to take dictation from the prince, and tells the boy to give orders as if he were King. The boy orders the end of the custom of [[kowtow]]ing, which Anna has greatly disliked. The King does not agree with the decision, but accepts it, hinting to his son that he must maintain a custom of showing respect for the king. As Chulalongkorn continues, prescribing a less arduous bow to show respect for the king, his father quietly dies. At first, this is only noticed by the Kralahome, but Anna notices as well, and kneels by the late King, holding his hand and kissing it. Wives and children bow or curtsey, a gesture of respect to old king and new. |

||

==Principal roles and notable performers== |

==Principal roles and notable performers== |

||

| Line 155: | Line 153: | ||

* March of the Royal Siamese Children — Orchestra |

* March of the Royal Siamese Children — Orchestra |

||

* A Puzzlement — King |

* A Puzzlement — King |

||

* The Royal Bangkok Academy — Anna, Wives |

* The Royal Bangkok Academy — Anna, Wives and Children |

||

* [[Getting to Know You (song)|Getting to Know You]] — Anna, Wives, and Children |

* [[Getting to Know You (song)|Getting to Know You]] — Anna, Wives, and Children |

||

* [[We Kiss in a Shadow]] — Tuptim and Lun Tha |

* [[We Kiss in a Shadow]] — Tuptim and Lun Tha |

||

| Line 161: | Line 159: | ||

* Shall I Tell You What I Think of You? — Anna |

* Shall I Tell You What I Think of You? — Anna |

||

* [[Something Wonderful (song)|Something Wonderful]] — Lady Thiang |

* [[Something Wonderful (song)|Something Wonderful]] — Lady Thiang |

||

* Buddhist Prayer/Act I finale — The King |

* Buddhist Prayer/Act I finale — The King and Company |

||

{{col-break}} |

{{col-break}} |

||

;Act II<ref name = "h148"/> |

;Act II<ref name = "h148"/> |

||

| Line 175: | Line 173: | ||

==Productions== |

==Productions== |

||

===Original productions=== |

===Original productions=== |

||

The |

''The King and I'' opened on [[Broadway theatre|Broadway]] on March 29, 1951, with a wide expectation of a hit. Both Hammerstein and Rodgers professed to be worried. The composer complained that most people were not concerned about whether the show was good, but whether it was better than ''South Pacific''. Even the weather cooperated—heavy rain in New York stopped a few minutes before curtain, allowing the royalty of Broadway to arrive dry at the [[St. James Theatre]].<ref>Hyland, p. 201</ref> Margaret Landon, author of the book on which the musical was based, was not invited to opening night.<ref>Morgan, p. 216</ref> Brynner turned in an outstanding performance on opening night, nearly stealing the show. Lawrence knew that the company was nervous about her performance because of her illnesses. As Van Druten described her opening night performance, however: "She came on the stage with a new and dazzling quality, as if an extra power had been granted to the brilliance of her stage light. She was radiant and wonderful."<ref>Hyland, p. 202</ref> The rave reviews lifted Lawrence's spirits, and she prepared herself for a lengthy run as Anna, first on Broadway, then in the [[West End theatre|West End]], and finally on film.<ref>Morley, p. 193</ref> Lawrence won a [[Tony Award]] for her leading role, while Brynner won the award for best featured (that is, secondary) actor.<ref name = "chapin"/> |

||

De Lappe remembered the contrast between Lawrence's indifferent singing voice and the force of her performance: |

De Lappe remembered the contrast between Lawrence's indifferent singing voice and the force of her performance: |

||

| Line 181: | Line 179: | ||

I used to listen to Gertrude Lawrence on the public address system every night in our dressing rooms, and she'd get onto a note and sag down off of it. The night after I left the show to go into ''[[Paint Your Wagon (musical)|Paint Your Wagon]]'', Yul Brynner gave me house seats and I saw her from the front and I was so taken by her. She had such a star quality, you didn't care if she sang off-key. She more than dominated the stage. Boy, was that a lesson to me.<ref name ="s311">Secrest, p. 311</ref> |

I used to listen to Gertrude Lawrence on the public address system every night in our dressing rooms, and she'd get onto a note and sag down off of it. The night after I left the show to go into ''[[Paint Your Wagon (musical)|Paint Your Wagon]]'', Yul Brynner gave me house seats and I saw her from the front and I was so taken by her. She had such a star quality, you didn't care if she sang off-key. She more than dominated the stage. Boy, was that a lesson to me.<ref name ="s311">Secrest, p. 311</ref> |

||

</blockquote> |

</blockquote> |

||

Lawrence |

Lawrence had not yet discovered that she was dying from [[Hepatocellular carcinoma|liver cancer]], and her weakened condition was exacerbated by the demands of her role. At the age of 52, she was required to wear dresses weighing 75 pounds while walking or dancing a total of four miles during a 3½ hour performance eight times a week. Lawrence found it hard to bear the heat in the theater during the summer months. Understudy [[Constance Carpenter]] began replacing her in matinee performances. In the fall, Lawrence's strength returned, and she resumed her full schedule, but by Christmas she was battling [[pleurisy]] and suffering from exhaustion. She the hospital for a full week of tests. Just nine months before her death, the cancer still was not detected. In February 1952, [[bronchitis]] felled her for another week, and Lawrence's husband Richard Aldrich asked Rodgers and Hammerstein if they would consider closing the show Easter week to allow her an opportunity to recover fully. They denied his request, but agreed to replace her with the original Ado Annie from ''Oklahoma!'', [[Celeste Holm]], for six weeks during the summer. In the meanwhile, Lawrence's performances were becoming increasingly worse, prompting audiences to become audibly restive. Rodgers and Hammerstein prepared a letter, never delivered, advising her that "eight times a week you are losing the respect of 1,500 people".<ref> Morley, pp. 191-96</ref> |

||

In late August, Lawrence fainted following a matinee and was admitted to [[NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital|New York Hospital]], where doctors diagnosed her as suffering from [[hepatitis]]. Her former son-in-law, Dr. Bill Cahan, suspected liver cancer might be a more accurate diagnosis, and early on the morning of September 6 doctors performed a biopsy of her liver. Lawrence slipped into a coma and died later that day, aged 54. The autopsy revealed Cahan's suggestion of cancer had been correct. On the day of her funeral, ''The King and I'' cancelled its performance.<ref>Morley, pp. |

In late August, Lawrence fainted following a matinee and was admitted to [[NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital|New York Hospital]], where doctors diagnosed her as suffering from [[hepatitis]]. Her former son-in-law, Dr. Bill Cahan, suspected liver cancer might be a more accurate diagnosis, and early on the morning of September 6, doctors performed a biopsy of her liver. Lawrence slipped into a coma and died later that day, aged 54. The autopsy revealed Cahan's suggestion of cancer had been correct. On the day of her funeral, ''The King and I'' cancelled its performance.<ref>Morley, pp. 197–98</ref> The lights of Broadway and the West End were dimmed; she was buried in the ball gown she wore during Act 2.<ref>Hammerstein, p. 207</ref> Carpenter assumed the role of Anna and went on to play it for 620 performances.<ref>Daniels, Lee A. [http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9F0CEEDD173DF932A35752C0A965958260 "Constance Carpenter obituary",] ''The New York Times'', January 1, 1993. Retrieved on January 23, 2011</ref> Other Annas during the 1,246–performance run included Holm, [[Annamary Dickey]] and [[Patricia Morison]].<ref name = "h149">Hischak, p. 149</ref> |

||

One young actor, [[Sal Mineo]], began as an extra, then became an understudy for a younger prince, then |

One young actor, [[Sal Mineo]], began as an extra, then became an understudy for a younger prince, then an understudy for Crown Prince Chulalongkorn. Mineo began a close friendship and working relationship with Brynner which would last over a decade. Another youthful performer, Ronnie Lee, who was a replacement for Louis Leonowens, Anna's son, was called upon to kneel next to the King's deathbed, on the side less visible to the audience. As he did this, in the final moments of the performance, Brynner would tell him dirty jokes, and the boy, appearing to be shaking with grief, would be shaking with laughter instead.<ref>Capua, p. 39</ref> |

||

A national tour ran for a year and |

A national tour ran for a year and nine months, and Brynner went from the Broadway company to the touring company when the show closed at the St. James Theatre. He boasted about never missing a show, though he actually missed several, once when stagehands accidentally struck him in the nose with a piece of scenery, another time due to appendicitis.<ref>Capua, p. 47</ref> A London production at the [[Drury Lane Theatre]] opened on October 8, 1953 and ran for 946 performances.<ref name = "h150"/> The London cast featured [[Valerie Hobson]], in her last role, as Anna, and [[Herbert Lom]] as the King.<ref name = "h150">Hischak, p. 150</ref> American [[Muriel Smith (singer)|Muriel Smith]] played Lady Thiang, and [[Martin Benson (actor)|Martin Benson]] played the Kralaholme (a role that he recreated in the film). <!-- THERE MUST BE MORE TO SAY ABOUT THE LONDON PRODUCTION, EVEN THOUGH YOUR SOURCES SEEM TO BE FOCUSING ON THE US PRODUCTIONS. Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre |

||

By Stanley Green, p. 233, has some info, but you need to get a better source for this production. --> |

|||

===Early revivals=== |

===Early revivals=== |

||

The first revival of ''The King and I'' in New York was presented by the [[New York City Center]] Light Opera Company in April 1956 for three weeks, starring [[Jan Clayton]] and [[Zachary Scott]], directed by John Fearnley with choreography by Jerome Robbins restaged by June Graham.<ref>Atkinson, Brooks. "Theatre:'The King and I' in Fine Revival", ''The New York Times'', April 19, 1956, p. 34</ref> This company presented the musical again in May 1960 with [[Barbara Cook]] and [[Farley Granger]], again directed by John Fearnley, in a limited engagement of three weeks (which had been extended from the original two weeks), or 23 performances.<ref>Atkinson, Brooks. "'The King and I':City Center Lengthens Current Engagement", ''The New York Times'', May 22, 1960. p. X1</ref> The company presented the show in June 1963 with [[Eileen Brennan]] and Manolo Fabregas and directed by Fearnley.<ref>Funke, Lewis |

The first revival of ''The King and I'' in New York was presented by the [[New York City Center]] Light Opera Company in April 1956 for three weeks, starring [[Jan Clayton]] and [[Zachary Scott]], directed by John Fearnley with choreography by Jerome Robbins restaged by June Graham.<ref>Atkinson, Brooks. "Theatre: 'The King and I' in Fine Revival", ''The New York Times'', April 19, 1956, p. 34</ref> This company presented the musical again in May 1960 with [[Barbara Cook]] and [[Farley Granger]], again directed by John Fearnley, in a limited engagement of three weeks (which had been extended from the original two weeks), or 23 performances.<ref>Atkinson, Brooks. "'The King and I': City Center Lengthens Current Engagement", ''The New York Times'', May 22, 1960. p. X1</ref> The company presented the show in June 1963 with [[Eileen Brennan]] and Manolo Fabregas and directed by Fearnley.<ref>Funke, Lewis. "Theater: 'The King And I'; Eileen Brennan Stars at City Center", ''The New York Times'', June 13, 1963, p. 28</ref><ref name="h150">Hischak, p. 150</ref> Michael Kermoyan played the King with [[Constance Towers]] in the City Center Light Opera production for three weeks in May 1968.<ref>(no author), "Entertainment events: Theater:Opening tonight", ''The New York Times'', May 23, 1968, p. 56</ref> |

||

The Music Theatre of [[Lincoln Center]], with Rodgers as producer, presented the musical in July 1964 at the [[New York State Theatre]] with [[Rise Stevens]] and [[Darren McGavin]], with [[Lee Venora]] as Tuptim and Michael Kermoyan as the Kralahome. The director was Edward Greenberg with the Robbins choreography reproduced by [[Yuriko (dancer)|Yuriko]] ( |

The Music Theatre of [[Lincoln Center]], with Rodgers as producer, presented the musical in July 1964 at the [[New York State Theatre]] with [[Rise Stevens]] and [[Darren McGavin]], with [[Lee Venora]] as Tuptim and Michael Kermoyan as the Kralahome. The director was Edward Greenberg, with the Robbins choreography reproduced by [[Yuriko (dancer)|Yuriko]] (who had played the role of Eliza in the original run). This was the first production of the newly-formed Music Theatre, with a limited engagement of five weeks.<ref name="h150"/><ref>Taubman, Howard. "Theater: 'The King and I' in New Surroundings; Lincoln Center Musical Troupe Makes Debut Rise Stevens Is Starred With Darren McGavin", ''The New York Times'', July 7, 1964, p. 26</ref><ref>Suskin, Steven.[http://www.playbill.com/features/article/131945-ON-THE-RECORD-Rodgers-Hammersteins-The-King-and-I-and-Flower-Drum-Song/all "On the Record"Rodgers & Hammerstein's The King and I and Flower Drum Song"] playbill.com, August 16, 2009</ref> |

||

A London revival in 1973 at the [[Adelphi Theatre]] starred [[Sally Ann Howes]] and [[Peter Wyngarde]].<!-- There were also several early regional productions, beginning with a MUNY production in 1964. See: http://www.floormic.com/show/120045 --> |

|||

===Brynner reprises the role, 1976–1985=== |

===Brynner reprises the role, 1976–1985=== |

||

In early 1976, Brynner received an offer from Broadway impresarios [[Lee Gruber]] and [[Shelly Gross]], urging him to star in a revival of ''The King and I''. Brynner reached terms with them, and spent much of early 1976 preparing for the role he had originated. The national tour of ''The King and I'' opened in Los Angeles on July 26, 1976, with [[Constance Towers]] as Anna. Choreography was again done by Yuriko. At the opening night, Brynner suffered so badly from laryngitis that his son Rock |

In early 1976, Brynner received an offer from Broadway impresarios [[Lee Gruber]] and [[Shelly Gross]], urging him to star in a revival of ''The King and I''. Brynner reached terms with them, and spent much of early 1976 preparing for the role he had originated. The national tour of ''The King and I'' opened in Los Angeles on July 26, 1976, with [[Constance Towers]] as Anna. Choreography was again done by Yuriko. At the opening night, Brynner suffered so badly from laryngitis that he lip-synched to his son Rock singing and speaking the role from the orchestra pit. The production traveled across the United States, selling out every city it appeared in, and finally opening in New York at the [[Uris Theatre]] (today the Gershwin Theatre) on May 2, 1977, with [[Angela Lansbury]] as Anna.<ref>Capua, pp. 144–47</ref> The production lasted 696 performances.<ref name = "h150"/> The tour was extended after the New York run, eventually reaching London in 1979, with [[Virginia McKenna]], as Anna, who won an [[Olivier Award]] for the role, [[John Bennett (actor)|John Bennett]] as the Kralahome and [[June Angela]] as Tuptim. Brynner insisted on renovations to the Uris Theatre before he would play there, stating that before the work was done, the Uris resembled "a public toilet".<ref name = "toilet"/> Brynner, who was required to spend a good part of his time at the theatre, insisted that dressing rooms be to his satisfaction, and, according to Brynner biographer Michelangelo Capua, was thanked by performers for years for having backstage facilities across the country cleaned up.<ref name = "toilet">Capua, pp. 148–149</ref> |

||

In August 1980, during the London run, Brynner announced that he would only take a few months off after the run concluded later that year, but would return to the role in an extended |

In August 1980, during the London run, Brynner announced that he would only take a few months off after the run concluded later that year, but would return to the role in an extended U.S. tour, which was to return to Broadway at its conclusion. The tour began in early 1981. On September 13, 1983 in Los Angeles, Brynner celebrated his 4,000th performance in his role as the King; on the same day he was privately diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. The tour returned to Broadway in January 1985 running for 191 performances with [[Mary Beth Peil]] as Anna and [[Patricia Welch]] as Tuptim, before concluding with a special Sunday night show in honor of Brynner on June 30, 1985. Piel was nominated for a Tony for her performance, while Brynner received a special award for his role as the King.<ref name = "death"/> According to Theodore Chapin, president of the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization, which licenses the pair's plays, "By the time Brynner gave his 4,525th and final performance in New York, the actress playing Mrs. Anna was neither mentioned nor pictured on the marquee of the theater."<ref name = "chapin"/> Chapin also notes that Piel was nominated for a featured actress Tony, so much had Brynner made the play his own.<ref name = "chapin"/> Brynner died less than four months after the end of the run, on October 10, 1985.<ref name = "death">Capua, pp. 151–57</ref><!-- I added some notable actor names here, but they also need to go in the role table above. --> |

||

===Post-Brynner productions=== |

===Post-Brynner productions=== |

||

The first production to break away from the original staging and interpretation was [[Christopher Renshaw]]'s production, first presented in Australia with [[Hayley Mills]] as Anna in 1991. The production had a more sinister Siamese setting, a less elegant but more forceful Anna, and a younger King (Tony Marinyo).<ref name = "h150"/> In this production, the attraction between Anna and the King is made explicit.<ref name = "s313"/> The production was moved to Broadway in 1996;<ref name = "h150"/> it opened on April 11, 1996 at the [[Neil Simon Theatre]] and closed on February 22, 1998 after 780 performances. The production starred [[Lou Diamond Phillips]] as the King, [[Donna Murphy]] as Anna, [[Randall Duk Kim]] as the Kralaholme, [[Jose Llana]] as Lun Tha, Joohee Choi as Tuptim and Taewon Kim as Lady Thiang. The production was directed by |

The first major production to break away from the original staging and interpretation was [[Christopher Renshaw]]'s production, first presented in Australia with [[Hayley Mills]] as Anna in 1991. The production had a more sinister Siamese setting, a less elegant but more forceful Anna, and a younger King (Tony Marinyo).<ref name = "h150"/> In this production, the attraction between Anna and the King is made explicit.<ref name = "s313"/> The production was moved to Broadway in 1996;<ref name = "h150"/> it opened on April 11, 1996 at the [[Neil Simon Theatre]] and closed on February 22, 1998 after 780 performances. The production starred [[Lou Diamond Phillips]] as the King, [[Donna Murphy]] as Anna, [[Randall Duk Kim]] as the Kralaholme, [[Jose Llana]] as Lun Tha, Joohee Choi as Tuptim and Taewon Kim as Lady Thiang. The production was directed by Renshaw. It won the [[Drama Desk Award]] for Outstanding Revival of a Musical and was nominated for eight [[Tony Award]]s. Both the book and score were revised and adapted.<ref>Flatow, Sheryl. [http://www.playbill.com/features/article/64313-How-Christopher-Renshaw-Crowned-a-New-King "How Christopher Renshaw Crowned a New King"]. Playbill.com, August 9, 1996</ref> [[Marie Osmond]] played the role of Anna later in the run, as did [[Faith Prince]]. The production toured in the U.S. during 1998 with Osmond and Victor Talmadge. Other Annas on this tour included [[Hayley Mills]], [[Sandy Duncan]] and [[Stefanie Powers]]. [[Maureen McGovern]] ended the tour in Chicago in June 1998.<ref>Winer, Laurie. [http://articles.latimes.com/1998/may/25/entertainment/ca-53229 "Osmond a Pretty, Petulant Anna in 'King and I'"]. ''Los Angeles Times'', May 25, 1998</ref><ref>Jones, Chris. [http://www.maureenmcgovern.com/chictrib.htm "This 'King' has an 'I' Maureen McGovern pours herself into Anna"]. ''Chicago Tribune'' (reprint at maureenmcgovern.com), June 15, 1998</ref> |

||

A production based on the 1996 Broadway revival opened on May 3, 2000 at the [[London Palladium]]. The cast included [[Elaine Paige]] (and subsequently [[Josie Lawrence]]) as Anna and [[Jason Scott Lee]] (and later [[Paul Nakauchi]] and Keo Woolford) as the King, with Taewon Yi Kim as Tuptin. This production was extremely well received and before the opening, the box office had already taken in excess of £7 million in ticket sales.<ref>Loveridge, Lizzie.[http://www.curtainup.com/kingandi.html "A CurtainUp London Review, 'The King and I'"] |

A production based on the 1996 Broadway revival opened on May 3, 2000 at the [[London Palladium]]. The cast included [[Elaine Paige]] (and subsequently [[Josie Lawrence]]) as Anna and [[Jason Scott Lee]] (and later [[Paul Nakauchi]] and Keo Woolford) as the King, with Taewon Yi Kim as Tuptin. This production was extremely well received, and before the opening, the box office had already taken in excess of £7 million in ticket sales.<ref>Loveridge, Lizzie. [http://www.curtainup.com/kingandi.html "A CurtainUp London Review, 'The King and I'"]. Curtainup.com, 3 May 2000</ref> The production closed on January 5, 2002 to make way for the musical ''[[Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (musical)|Chitty Chitty Bang Bang]]''.<ref>[http://www.albemarle-london.com/Archive/ArchiveShow.php?Show_Name=King%20and%20I "The King and I archives, London Palladium"]. Albemarle-london.com, retrieved March 7, 2010</ref> |

||

==Film and television versions== |

==Film and television versions== |

||

{{Main|The King and I (1956 film)|The King and I (1999 film)}} |

{{Main|The King and I (1956 film)|The King and I (1999 film)}} |

||

The musical was filmed in 1956 with Brynner re-creating his role opposite [[Deborah Kerr]]. The film won 5 [[Academy Awards]] and was nominated for four more. Brynner won an Oscar as [[Academy Award for Best Actor|Best Actor]] for his portrayal, and Kerr was nominated as [[Academy Award for Best Actress|Best Actress]]. The film also won for best music.<ref name = "h151"/> |

The musical was filmed in 1956 with Brynner re-creating his role opposite [[Deborah Kerr]]. The film won 5 [[Academy Awards]] and was nominated for four more. Brynner won an Oscar as [[Academy Award for Best Actor|Best Actor]] for his portrayal, and Kerr was nominated as [[Academy Award for Best Actress|Best Actress]]. The film also won for best music. [[Marni Nixon]] dubbed the voice of Anna, while [[Rita Moreno]] played Tuptim.<ref name = "h151"/> |

||

[[RichCrest Animation Studios]] and [[Morgan Creek Productions]] released a new, animated adaptation of the musical in 1999. However, except for using some of the songs, the story was unrelated to the Rodgers and Hammerstein version. Geared towards children, the adaptation included a number of cuddly animals, including a dragon. Hischak notes that one compensation of the film is hearing [[Barbara Streisand]] sing "Something Wonderful", but states, "it is more surprising to think that the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization allowed it to be made" and "children have enjoyed ''The King and I'' for five decades without dancing dragons".<ref name = "h151">Hischak, p. 151</ref> |

[[RichCrest Animation Studios]] and [[Morgan Creek Productions]] released a new, animated adaptation of the musical in 1999. However, except for using some of the songs, the story was unrelated to the Rodgers and Hammerstein version. Geared towards children, the adaptation included a number of cuddly animals, including a dragon. Hischak notes that one compensation of the film is hearing [[Barbara Streisand]] sing "Something Wonderful", but states, "it is more surprising to think that the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization allowed it to be made" and "children have enjoyed ''The King and I'' for five decades without dancing dragons".<ref name = "h151">Hischak, p. 151</ref> <!-- THE HEADING INDICATES that there will be a discussion of the TV series here. Was it related to the musical? --> |

||

==Music and recordings== |

==Music and recordings== |

||

| Line 224: | Line 225: | ||

Kenrick recommends the 1964 Lincoln Center cast recording—the first time "The Small House of Uncle Thomas" was recorded—noting the performances of [[Rise Stevens]] as Anna and [[Patricia Neway]] (who had originated the Mother Abbess in ''[[The Sound of Music]]'') as Lady Thiang.<ref name = "ken"/> Such an inclusion was especially notable, as LP technology limited a single-disc album to about fifty minutes, and thus inclusion of the ballet required the exclusion of some of the other numbers.<ref>Mordden, p. 143</ref> "The Small House of Uncle Thomas" is omitted in the 1977 Broadway revival recording with Brynner and [[Constance Towers]]. Hischak notes that some might prefer Brynner in his earlier recordings, when his voice was more vibrant.<ref name = "h152"/> Kenrick recommends the 1992 Angel recording for its casting of [[Julie Andrews]] in a role she never played on stage.<ref name = "ken"/> The 1996 Broadway revival recording was applauded by Kenrick for the performance of [[Lou Diamond Phillips]] as the King, calling him "that rarity, a King who can stand free of Brynner's shadow".<ref name = "ken">Kenrick, John.[http://www.musicals101.com/cdcomps3.htm "Comparative CD Reviews: Part III. The King and I"] (Copyright 1998-2003); retrieved January 11, 2011</ref> Hischak finds the soundtrack to the 1999 animated film with [[Christiane Noll]] as Anna and [[Martin Vidnovic]] as the King more enjoyable than the movie itself,<ref name = "h152"/> while Kenrick's sole use for that CD is as a coaster.<ref name = "ken"/> |

Kenrick recommends the 1964 Lincoln Center cast recording—the first time "The Small House of Uncle Thomas" was recorded—noting the performances of [[Rise Stevens]] as Anna and [[Patricia Neway]] (who had originated the Mother Abbess in ''[[The Sound of Music]]'') as Lady Thiang.<ref name = "ken"/> Such an inclusion was especially notable, as LP technology limited a single-disc album to about fifty minutes, and thus inclusion of the ballet required the exclusion of some of the other numbers.<ref>Mordden, p. 143</ref> "The Small House of Uncle Thomas" is omitted in the 1977 Broadway revival recording with Brynner and [[Constance Towers]]. Hischak notes that some might prefer Brynner in his earlier recordings, when his voice was more vibrant.<ref name = "h152"/> Kenrick recommends the 1992 Angel recording for its casting of [[Julie Andrews]] in a role she never played on stage.<ref name = "ken"/> The 1996 Broadway revival recording was applauded by Kenrick for the performance of [[Lou Diamond Phillips]] as the King, calling him "that rarity, a King who can stand free of Brynner's shadow".<ref name = "ken">Kenrick, John.[http://www.musicals101.com/cdcomps3.htm "Comparative CD Reviews: Part III. The King and I"] (Copyright 1998-2003); retrieved January 11, 2011</ref> Hischak finds the soundtrack to the 1999 animated film with [[Christiane Noll]] as Anna and [[Martin Vidnovic]] as the King more enjoyable than the movie itself,<ref name = "h152"/> while Kenrick's sole use for that CD is as a coaster.<ref name = "ken"/> |

||

==Critical reception== |

==Critical reception==<!-- I HAVEN'T READ THIS SECTION YET, BUT IT LOOKS A BIT SKIMPY. --> |

||

The opening night brought warm reviews of the musical. Richard Watts in the [[New York Post|New York ''Post'']] termed it "another triumph for the masters".<ref name = "h149"/> Critic [[John Mason Brown]] stated, "They have done it again."<ref name = "h202">Hyland, p. 202</ref> ''The New York Times'' drama critic, [[Brooks Atkinson]] wrote, "This time Messrs. Rodgers and Hammerstein are not breaking any fresh trails, but they are accomplished artists of song and words in the theater; and ''The King and I'' is a beautiful and lovable musical play."<ref>Fordin, p. 303</ref> Less enthusiastic was [[John Lardner]] in the ''[[New Yorker]]'', who wrote, "Even those of us who find <nowiki>[the Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals]</nowiki> a little too unremittingly wholesome are bound to take pleasure in the high spirits and technical skill that their authors, and producers have put into them."<ref name = "s313">Secrest, p. 313</ref> [[Otis Guernsey]] wrote for the [[New York Herald Tribune|New York ''Herald Tribune'']], "Musicals and leading men will never be the same after last night ... Brynner set an example that will be hard to follow ... Probably the best show of the decade.<ref>Capua, p. 36</ref> |

The opening night brought warm reviews of the musical. Richard Watts in the [[New York Post|New York ''Post'']] termed it "another triumph for the masters".<ref name = "h149"/> Critic [[John Mason Brown]] stated, "They have done it again."<ref name = "h202">Hyland, p. 202</ref> ''The New York Times'' drama critic, [[Brooks Atkinson]] wrote, "This time Messrs. Rodgers and Hammerstein are not breaking any fresh trails, but they are accomplished artists of song and words in the theater; and ''The King and I'' is a beautiful and lovable musical play."<ref>Fordin, p. 303</ref> Less enthusiastic was [[John Lardner]] in the ''[[New Yorker]]'', who wrote, "Even those of us who find <nowiki>[the Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals]</nowiki> a little too unremittingly wholesome are bound to take pleasure in the high spirits and technical skill that their authors, and producers have put into them."<ref name = "s313">Secrest, p. 313</ref> [[Otis Guernsey]] wrote for the [[New York Herald Tribune|New York ''Herald Tribune'']], "Musicals and leading men will never be the same after last night ... Brynner set an example that will be hard to follow ... Probably the best show of the decade.<ref>Capua, p. 36</ref> |

||

| Line 246: | Line 247: | ||

==Awards and nominations== |

==Awards and nominations== |

||

{{col-begin}} |

|||

{{col-2}} |

|||

'''1952 [[Tony Award]]'''<ref name = "tony">{{Cite web | title = Search past winners—''The King and I'' | work = Tony Awards | publisher = American Theatre Wing | url = http://www.tonyawards.com/p/tonys_search?start=0&year=&award=&lname=&fname=&show=%3Ci%3EThe%20King%20and%20I%3C%2Fi%3E | accessdate = January 13, 2011}}</ref> |

'''1952 [[Tony Award]]'''<ref name = "tony">{{Cite web | title = Search past winners—''The King and I'' | work = Tony Awards | publisher = American Theatre Wing | url = http://www.tonyawards.com/p/tonys_search?start=0&year=&award=&lname=&fname=&show=%3Ci%3EThe%20King%20and%20I%3C%2Fi%3E | accessdate = January 13, 2011}}</ref> |

||

* Best Musical '''WINNER''' |

* Best Musical '''WINNER''' |

||

| Line 259: | Line 262: | ||

'''1979 [[Olivier Award]]s'''<ref name = "olive">{{Cite web | title = Official London Theatre listing, 1979 Olivier Awards | work = Olivier Awards | publisher = Official London Theatre | url = http://www.officiallondontheatre.co.uk/olivier_awards/past_winners/view/item98513/Olivier-Winners-1979/| accessdate = January 13, 2011}}</ref> |

'''1979 [[Olivier Award]]s'''<ref name = "olive">{{Cite web | title = Official London Theatre listing, 1979 Olivier Awards | work = Olivier Awards | publisher = Official London Theatre | url = http://www.officiallondontheatre.co.uk/olivier_awards/past_winners/view/item98513/Olivier-Winners-1979/| accessdate = January 13, 2011}}</ref> |

||

* Best Actress in a Musical |

* Best Actress in a Musical — [[Virginia McKenna]] '''WINNER''' |

||

'''1985 Tony Award'''<ref name = "tony"/> |

'''1985 Tony Award'''<ref name = "tony"/> |

||

* Special |

* Special Award — Yul Brynner |

||

* Best Featured Actress in a Musical — [[Mary Beth Peil]] (nominee) |

* Best Featured Actress in a Musical — [[Mary Beth Peil]] (nominee) |

||

* Best Direction of a Musical — Mitch Leigh (nominee) |

* Best Direction of a Musical — Mitch Leigh (nominee) |

||

{{col-break}} |

|||

'''1996 Tony Award'''<ref name = "tony"/> |

'''1996 Tony Award'''<ref name = "tony"/> |

||

| Line 290: | Line 294: | ||

* Best Set Designer - Brian Thomson (nominee) |

* Best Set Designer - Brian Thomson (nominee) |

||

* Best Costume Designer - Roger Kirk (nominee) |

* Best Costume Designer - Roger Kirk (nominee) |

||

{{col-end}} |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 316: | Line 321: | ||

*[http://www.rnh.com/show_detail.asp?id=KI&s=1 "The King and I" on R&H Theatricals site] |

*[http://www.rnh.com/show_detail.asp?id=KI&s=1 "The King and I" on R&H Theatricals site] |

||

*{{IMDB title|68039|Anna and the King (TV Series; 1972)}} |

*{{IMDB title|68039|Anna and the King (TV Series; 1972)}} |

||

*[http://www. |

*[http://www.vandaprints.com/image.php?id=326654 Photo of Hobson and Lom in the original London production] |

||

*[http://www.ovrtur.com/content/show.php?id=120045 Ovrtur.com Listing] |

*[http://www.ovrtur.com/content/show.php?id=120045 Ovrtur.com Listing] |

||

* [http://www.newcastletheatreco.net/ Newcastle Upon Tyne Musical Theatre Company] |

|||

{{DramaDesk MusicalRevival}} |

{{DramaDesk MusicalRevival}} |

||

Revision as of 02:07, 25 January 2011

| The King and I | |

|---|---|

Poster for the original Broadway production | |

| Music | Richard Rodgers |

| Lyrics | Oscar Hammerstein II |

| Book | Oscar Hammerstein II |

| Basis | Novel by Margaret Landon Anna and the King of Siam |

| Productions | 1951 Broadway 1953 West End 1956 Film 1977 Broadway revival 1979 West End revival 1985 Broadway revival 1996 Broadway revival 1999 Animated film 2000 West End revival |

| Awards | 1952 Tony Award for Best Musical 1996 Tony Award for Best Revival |

The King and I is a 1951 stage musical, the fifth by the team of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II. The play is based on the 1944 novel Anna and the King of Siam by Margaret Landon and derives from the memoirs of Anna Leonowens, who became governess to the children of King Mongkut of Siam in the early 1860s. The story deals with the experiences of the British schoolteacher, who is hired as part of the King's drive to modernize his country. Anna and the King struggle to come to a mutual understanding despite their contrasting cultural backgrounds. She also assists Tuptim, one of the King's slaves, who wishes to escape from the court with the man she loves.

In 1950, theatrical attorney Fanny Holtzmann was looking for a part for her client, Broadway and London legend Gertrude Lawrence. Holtzmann realized that Landon's book would be an ideal vehicle and contacted Rodgers and Hammerstein, who were initially reluctant, but agreed to write the musical. The pair initially sought Rex Harrison to play the supporting part of the King—he had played the role in the 1946 movie made from Landon's book—but Harrison was unavailable. They settled on Russian-American actor Yul Brynner.

The musical opened on March 29, 1951 and was an immediate hit, winning 1952 Tony Awards for Best Musical, Best Actress (for Lawrence) and Best Featured Actor (for Brynner), among others. Lawrence died unexpectedly of cancer a year and a half after the opening, and the role of Anna was played by other actresses after she left the cast during the Broadway run of 1,246 performances. A national tour and a hit London run followed, together with a 1956 film for which Brynner won an Academy Award. The musical has been repeatedly revived in the sixty years of its life, and before his 1985 death, Brynner converted the work into a star vehicle for himself.

Historical background

In 1861, Mongkut, King of Siam, wrote to his Singapore agent, Tan Kim Ching, asking him to find a British lady to be governess to the royal children. At the time, the British community in Singapore was small, and the choice fell on a recent arrival there, Anna Leonowens, who was running a small nursery school in the colony.[1] Leonowens was the mixed-race daughter of an Indian Army soldier and widow of a clerk and hotel keeper—she had arrived in Singapore two years previously, claiming to be the genteel widow of an officer and explaining her dark appearance by stating she was Welsh by birth. Her imposture was not detected in her lifetime.[2]

Leonowens sent her daughter, Avis, off to school in England, in the hope that her daughter would become the lady her mother pretended to be, and embarked for Bangkok with her five-year-old son, Louis, aboard the Chao Prya, commanded by Captain Orton.[1] King Mongkut had sought an English lady to teach his children after he had tried local missionaries, who used the opportunity to proselytize. Leonowens initially asked for $150 in Singapore currency per month. Another request by Leonowens, that she live in or near the missionary community for Western company, aroused suspicion in Mongkut, who noted in a letter, "we need not have teacher of Christianity as they are abundant here".[3] King Mongkut and Leonowens came to an agreement—$100 per month and a residence near the royal palace. At a time when the streets of Bangkok were canals, Mongkut did not wish to have to arrange for the teacher's transport every day.[3] The Leonowens family temporarily lived as guests of Mongkut's prime minister, and after the first house offered was found to be unsuitable, the family moved into a brick residence (wooden structures decayed quickly in Bangkok's climate) on the same side of the river as the palace, and within walking distance.[3]

King Mongkut himself was aged about 57 in 1861. He had lived half his life as a Buddhist monk and had proved an able scholar, founding a new order of Buddhism and a temple in Bangkok (paid for by his half-brother, King Jessadabodindra). When Jessadabodindra died in 1850, Mongkut became king. Through his decades of devotion, Mongkut had acquired an ascetic lifestyle and a firm grasp of Western languages. Mongkut came to the throne at a time when various European countries, as well as American traders, were striving for dominance in Southeast Asia, and his plans (ultimately successful) to keep Siam an independent nation involved familiarizing his heirs and harem with Western ways.[4]

Inception

In 1950, stage legend Gertrude Lawrence's business manager and attorney Fanny Holtzmann was looking for a new property for her client, when the 1944 Margaret Landon book Anna and the King of Siam (a fictionalized version of Leonowens' experiences) was sent to her by Landon's William Morris agent.[5] According to Rodgers biographer Meryle Secrest, Holtzmann was worried that Lawrence's career was fading.[6] In any case, Lawrence had appeared in plays rather than musicals since the revival of Lady in the Dark in 1943.[7] Holtzmann agreed that a musical based on Anna and the King of Siam would be ideal for Lawrence.[5] Lawrence purchased the stage rights to the book.[8] Holtzmann initially wanted Cole Porter to write the score, but he refused. Holtzmann was going to approach Noël Coward next, but happened to meet Dorothy Hammerstein (Oscar's wife) in Manhattan. Holtzmann told Dorothy Hammerstein that she wanted Rodgers and Hammerstein to do a show for Lawrence, and to see that her husband read a book that Holtzmann would send over. Both Dorothy Rodgers and Dorothy Hammerstein were under instructions to pass along all such messages to their husbands, and Dorothy Hammerstein did so. In fact, both wives had read the book, when it was first published, and had urged their husbands to consider it as a possible subject for a musical.[5]