Coat of arms of England: Difference between revisions

Replaced infobox, there are problems with it but let's discuss on talk page; but reverted to my previous version of text |

|||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

|use = [[National symbols of England|National symbol of England]] |

|use = [[National symbols of England|National symbol of England]] |

||

}} |

}} |

||

[[File:UK Arms 1837.svg |thumb|200px|The Royal Arms of England from 1837 to the present. The [[blazon]] may be summarised as: ''[[Quartering (heraldry)|Quarterly]]: 1st & 4th England; 2nd Scotland; 3rd Ireland''. The [[Escutcheon (heraldry)|escutcheon]] is properly shown encircled with the [[Order of the Garter|Garter]]<ref>Debrett's Peerage, 1968, p.2</ref>]] |

|||

In [[heraldry]], the '''Royal Arms of England'''<ref>{{harvnb|Jamieson|1998|pp=14–15}}.</ref> is a [[coat of arms]] symbolising [[England]] and [[List of English monarchs|its monarchs]].<ref name=boutell373>{{Harvnb|Boutell|1859|p=373}}: "The three golden lions upon a ground of red have certainly continued to be the royal and national arms of England."</ref> Its [[blazon]] (technical description) is ''Gules three lions passant guardant in pale Or armed and langued Azure'',<ref name=fd607>{{harvnb|Fox-Davies|2008|p=607}}.</ref><ref name=Blazon01 >{{cite web |url=http://footguards.tripod.com/08HISTORY/08_heraldry.htm |title=Coat of Arms of King George III |author=The First Foot Guards |publisher=footguards.tripod.com|date= |accessdate=4-February-2010 }}</ref> meaning three identical gold [[lion (heraldry)|lion]]s with blue tongues and claws, walking and facing the observer, arranged in a column on a red background. This coat, designed in the [[High Middle Ages]], has been variously combined with those of France, Scotland, Ireland, [[House of Nassau|Nassau]] and [[Kingdom of Hanover|Hanover]], according to dynastic and other political changes affecting England, but has not itself been altered since the reign of [[Richard I of England|Richard I]]. |

|||

[[File:Royal Arms of England (1198-1340).svg|thumb|200px|Arms of Plantagenet ("England"): ''Gules, three lions passant guardant in pale or'']] |

|||

[[File:Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom.svg|thumb|200px|The heraldic [[Achievement (heraldry)|achievement]] of the [[Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom]] with escutcheon encircled with Garter, crest, supporters and motto as used by Queen Elizabeth II from 1953. The arms of Plantagenet ("England") occupy the 1st & 4th [[quarter (heraldry)|quarter]]s of greatest honour. This is the form of Royal Arms which symbolises Her Majesty's Government of the UK, and is seen in government buildings and on government correspondence]] |

|||

In [[heraldry]], the '''Royal Arms of England'''<ref>{{harvnb|Jamieson|1998|pp=14–15}}.</ref> is a [[coat of arms]] used exclusively by the [[List of English monarchs|English monarch]]. It forms an expression and symbol of royal power, exercised (now democratically) by Her Majesty's Government, and is thus displayed prominently within government buildings and within courts dispensing royal justice, on the letter-heads of the [[Inland Revenue]], a branch of Her Majesty's [[Treasury]] and in other such contexts. More widely the Royal Arms may be seen to symbolise the nation of the [[United Kingdom]] of [[Kingdom of England|England]], [[Kingdom of Scotland|Scotland]] and [[Northern Ireland]], which nation is however more properly signified by the national emblem of the [[Union Flag]]. <ref name=boutell373>{{Harvnb|Boutell|1859|p=373}}: "The three golden lions upon a ground of red have certainly continued to be the royal and national arms of England."</ref> The earliest constituent of the current [[Quartering (heraldry)|quartered]] arms is the "Lions of Plantagenet". This is [[blazon]]ed (technical heraldic description) as: ''Gules, three [[Lion (heraldry)|lions passant guardant]] in pale or armed and langued azure'',<ref name=fd607>{{harvnb|Fox-Davies|2008|p=607}}.</ref><ref name=Blazon01 >{{cite web |url=http://footguards.tripod.com/08HISTORY/08_heraldry.htm |title=Coat of Arms of King George III |author=The First Foot Guards |publisher=footguards.tripod.com|date= |accessdate=4-February-2010 }}</ref> signifying three identical gold [[lion (heraldry)|lion]]s with blue tongues and claws, in the act of walking past, but with head facing toward, the observer, arranged one above the other in a column on a red field (i.e. background). These arms when incorporated into quarterings of other families, for example of royal dukes, may be correctly blazoned simply as "England". These arms of Plantagenet were adopted in simple and primitive form, as a single lion or a pair, after the accession of [[Henry II of England|King Henry II]](1154-1189), son of [[Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou]], and became fixed in their present triple form and tinctures during the reign of his son and heir [[Richard I of England|Richard I]](1189-1199). The first use of heraldic arms spread rapidly to the nobility and knights from about 1200 to 1215. The arms of Plantagenet have been variously quartered by English monarchs with the royal arms of France, Scotland, Ireland, the [[House of Nassau]] and [[Kingdom of Hanover]], according to dynastic and other political alliances and marriages entered into by English monarchs. |

|||

| ⚫ | Although royal emblems depicting lions were used by the [[Norman dynasty]],<ref name="Boutell"/><ref name=bl_royal3>{{harvnb|Brooke-Little|1981|p=3–6}}</ref><ref name=paston114>{{harvnb|Paston-Bedingfield|Gwynn-Jones|1993|pp=114–115}}.</ref> a formal and consistent [[English heraldry]] |

||

| ⚫ | Although royal emblems depicting lions were used by the [[Norman dynasty]],<ref name="Boutell"/><ref name=bl_royal3>{{harvnb|Brooke-Little|1981|p=3–6}}</ref><ref name=paston114>{{harvnb|Paston-Bedingfield|Gwynn-Jones|1993|pp=114–115}}.</ref> as can be seen on certain shields in the [[Bayeux Tapestry]](1066), a formal and consistent system of [[English heraldry]] emerged during the very early 13th century. The [[Escutcheon (heraldry)|escutcheon]], or shield, featuring three lions is traceable back to King Richard I's [[Great Seal of the Realm]], which initially used a single lion rampant, or a pair of lions, but in 1198, was permanently altered to depict three lions passant.<ref name=Blazon01/><ref name="Boutell"/><ref name=bl_royal3/><ref name=paston114/> In 1340, [[Edward III of England|King Edward III]] laid claim to the [[King of France|throne of France]] and quartered his paternal arms of Plantagenet with those of the [[Kingdom of France|King of France]].<ref name="Boutell">{{harvnb|Brooke-Little|1950|pp=205–222}}.</ref> This quartering was adjusted, abandoned and restored intermittently throughout the Middle Ages as the relationship between England and France changed. Since the [[Union of the Crowns]] in 1603, when the kingdoms of England and [[Kingdom of Scotland|Scotland]] entered a union, which in substance was a [[Feudalism|feudal]] [[personal union]] between the two monarchs, the English king added to his arms a quartering of the arms of the king of Scotland to form the large part of what has now become the arms of the monarch of the [[United Kingdom]], termed popularly the [[Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom]], although strictly they are personal family arms of the monarch.<ref name="britmon">{{cite web|url=http://www.royal.gov.uk/MonarchUK/Symbols/UnionJack.aspx |title=Union Jack |accessdate=2009-08-28 |author=The Royal Household|publisher=royal.gov.uk}}</ref> "The Lions of England" appear in a similar capacity to represent England in the [[Arms of Canada]] and the [[Queen's Personal Canadian Flag]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=518&ProjectElementID=1811|title=The Flag of Her Majesty the Queen for personal use in Canada|author=The Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada|accessdate=2009-08-28|date=|publisher=gg.ca}}</ref> The coat of three lions continues to represent England on several [[coins of the pound sterling]], forms the basis, with altered tinctures, of several emblems of English national sports teams, <ref name=briggs>{{harvnb|Briggs|1971|pp=166–167}}.</ref><ref name=why>{{cite web|url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/football/2002/jul/18/theknowledge.sport|publisher=guardian.co.uk|title=Why do England have three lions on their shirts?|date=2002-07-18|accessdate=2010-09-15|first=Sean|last=Ingle}}</ref> and endures as one of the most recognisable [[national symbols of England]].<ref name=boutell373/> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The Royal Arms in the form of a [[heraldic flag]] signifies the presence of the monarch in person within the building or vehicle from which it flies. It is variously known as the '''Royal Banner of England''',<ref>{{harvnb|Thompson|2001|p=91}}.</ref> the '''Banner of the Royal Arms''',<ref name=fd474/> the '''Banner of the King of England''',<ref>{{harvnb|Keightley|1834|p=310}}.</ref><ref>{{harvnb|James|2009|p=247}}.</ref> or by the [[misnomer]] of the '''Royal Standard of England'''.{{#tag:ref|In ''A Complete Guide to Heraldry'' (1909), [[Arthur Charles Fox-Davies]] explains:{{cquote|It is a [[misnomer]] to term the banner of the Royal Arms the Royal Standard. The term standard properly refers to the long tapering flag used in battle, by which an overlord mustered his retainers in battle.<ref name=fd474>{{Harvnb|Fox-Davies|1909|p=474}}.</ref>}}The archaeologist and antiquarian [[Charles Boutell]] also makes this distinction.<ref name=journal/>|group=note}} This Royal Banner differs entirely from England's [[national flag]], [[Flag of England|St George's Cross]], in that it does not represent any particular area or land, but rather symbolises the monarch herself. It is essentially the remnant of feudal usage, to inform as to the physical presence of a great lord, and such personal banners are still used by many of the great and ancient English ducal families in a similar manner, for example they are flown from a flagstaff on the duke's home when he is in residence and removed when he has departed <ref name=fd607>{{harvnb|Fox-Davies|2008|p=607}}.</ref> |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

===Origins=== |

===Origins=== |

||

{{see also|English heraldry|Armorial of Plantagenet}} |

{{see also|English heraldry|Armorial of Plantagenet}} |

||

[[File:Richard I 2nd seal.png|thumb| |

[[File:Richard I 2nd seal.png|thumb|200px|The battle-shield of [[Richard I of England|King Richard I]](1189-1199), grandson of [[Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou]] on which are depicted 3 lions passant guardant, the earliest known fixed example of the heraldic Arms of Plantagenet, the Royal arms of the English kings. Detail from the second [[Great Seal of the Realm|Great Seal]] of King Richard I]] |

||

[[File:Geoffrey of Anjou Monument.jpg|thumb|200px|The battle-shield used by [[Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou]](d.1151) as depicted in enamel on his tomb(c.1151) at [[Le Mans]] shows the origin of the ''Lions of Plantagenet''. It was decorated with 7 lions, 4 of which are visible to the viewer the remaining 3 being hidden by the curvature of the shield. This device was merely an informal [[recognisance]] or personal emblem as heraldry proper, with its own rules of usage, did not appear in France and England until the very early 13th.c.]] |

|||

Lions had previously been used by the [[Norman dynasty]] as royal emblems, and [[ |

Lions had previously been used by the [[Norman dynasty]] as royal emblems, and imaginary arms, known as [[attributed arms]], have been allocated by their descendants to kings who pre-dated the introduction of hereditary [[English heraldry]] which spread into general usage in the very early 13th.c.<ref name="Boutell"/> [[Henry II of England|King Henry II]](1154-1189), son of Geoffrey Plantagenet, used used a shield with two lions on it,<ref name="Ailes">{{cite book |last=Ailes |first=Adrian |title=The Origins of The Royal Arms of England|year=1982 |publisher=Graduate Center for Medieval Studies, University of Reading |location=Reading |pages=52–63}}</ref> an apparent variation on the usage of his father, as appears from a half-view of his shield on his seal. His two sons experimented with different combinations of lions. The battle-shield of [[Richard I of England|Richard the Lionheart]], in half-view, shows a single lion rampant, or perhaps two lions affrontés, as depicted on his first seal,<ref name=Blazon01/> but his later shield showed three lions passant guardant as depicted on his 1198 [[Great Seal of the Realm|Great Seal of England]], and thus established the lasting design of the Royal Arms of England.<ref name=Blazon01/><ref name=Ailes/> Although in 1177 his younger brother the future [[John I of England|King John]](1199-1216) used a seal showing a shield with two lions passant guardant, the three golden lions passant guardant on a red field were used as the Royal Arms by John after he had become king in 1199 and by his son [[Henry III of England|Henry III]](1216-1272) and by future kings until Edward III(1327-1377),<ref name=Blazon01/> who in 1340 [[Quartering (herldry)|quartered]] them with the arms of the King of France, with the arms of France placed in the quarters of greatest honour, as arms of [[pretender|pretence]], as a symbol of his claim to the French throne. |

||

===Crest=== |

|||

In 1362, Edward III, one of whose titles was Lord of Aquitaine, used the arms of the Counts of Aquitaine as his [[crest (heraldry)|crest]], and made his eldest son [[Edward the Black Prince]] Prince of Aquitaine. In 1390, The Black Prince's son King [[Richard II of England|King Richard II]] appointed his uncle [[John of Gaunt]] as Duke of Aquitaine. This title again passed on to [[Henry V of England|Henry IV]] (1399), who inherited the duchy from his father, but ceded it to his son upon becoming [[King of England]]. Henry V continued to rule over Aquitaine as King of England and Lord of Aquitaine. The Lion of Aquitaine has remained the Royal Crest of England since the reign of Edward III. |

|||

===Development=== |

===Development=== |

||

{{see also|English claims to the French throne|Union of the Crowns}} |

{{see also|English claims to the French throne|Union of the Crowns}} |

||

In 1340, following the death of King [[Charles IV of France]], [[Edward III of England|Edward III]] asserted [[English claims to the French throne|a claim to the French throne]] through his mother [[Isabella of France]]. In addition to initiating the [[Hundred Years' War]], Edward III expressed his claim in heraldic form by quartering the royal arms of England with the [[National Emblem of France#History|Arms of France]]. This quartering continued until 1801, with intervals in 1360–1369 and 1420–1422.<ref name=Blazon01/> |

In 1340, following the death of King [[Charles IV of France]], [[Edward III of England|Edward III]] asserted [[English claims to the French throne|a claim to the French throne]] through his mother [[Isabella of France]]. In addition to initiating the [[Hundred Years' War]], Edward III expressed his claim in heraldic form by adopting "arms of [[Pretender|pretence]]" by [[quartering (heraldry)|quartering]] the royal arms of England with the [[National Emblem of France#History|Arms of France]] (''France Ancien''), and furthermore placed the French arms in the 1st & 4th quarters of greatest honour, generally reserved for the paternal arms, as a recognition of quasi-feudal superiority of the King of France. This quartering continued until 1801, with intervals in 1360–1369 and 1420–1422.<ref name=Blazon01/> |

||

Following the death of Queen [[Elizabeth I of England]] in 1603, the throne of England was inherited by the Scottish [[House of Stuart]], resulting in the [[Union of the Crowns]]: the Kingdom of England and Kingdom of Scotland were united in a [[personal union]] under King [[James I of England|James I of England and VI of Scotland]].<ref>{{Harvnb|Ross|2002|p=56|quote=''1603:'' James VI becomes [[James I of England]] in the [[Union of the Crowns]], and leaves Edinburgh for London}}.</ref> As a consequence, the Royal Arms of England and Scotland were combined in the king's new personal arms. Nevertheless, although referencing the personal union with Scotland and Ireland, the Royal Arms of England remained distinct from the [[Royal Arms of Scotland]], until the two realms were joined in a [[political union]] in 1707, leading to a unified [[Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom]].<ref name="britmon"/> |

Following the death of Queen [[Elizabeth I of England]] in 1603, the throne of England was inherited by the Scottish [[House of Stuart]], resulting in the [[Union of the Crowns]]: the Kingdom of England and Kingdom of Scotland were united in a [[personal union]] under King [[James I of England|James I of England and VI of Scotland]].<ref>{{Harvnb|Ross|2002|p=56|quote=''1603:'' James VI becomes [[James I of England]] in the [[Union of the Crowns]], and leaves Edinburgh for London}}.</ref> As a consequence, the Royal Arms of England and Scotland were combined in the king's new personal arms. Nevertheless, although referencing the personal union with Scotland and Ireland, the Royal Arms of England remained distinct from the [[Royal Arms of Scotland]], until the two realms were joined in a [[political union]] in 1707, leading to a unified [[Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom]].<ref name="britmon"/> |

||

| Line 52: | Line 60: | ||

! width=70%|Description |

! width=70%|Description |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Image:Henry II arms.png|75px|center]]||1154–1189||[[Henry II of England|King Henry II]], the first king from the House of Plantagenet, is thought to have used pair of lions passant in his personal arms. Although the tinctures of Henry's coat are unknown, some descendants used a similar coat with gold lions on red.<ref name=Ailes/> These arms |

| [[Image:Henry II arms.png|75px|center]]||1154–1189||[[Henry II of England|King Henry II]], the first king from the House of Plantagenet, is thought to have used pair of lions passant in his personal arms. Although the tinctures of Henry's coat are unknown, some descendants used a similar coat with gold lions on red.<ref name=Ailes/> These arms were later allocated as [[attributed arms]] to [[William the Conquerer]]. |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| <center>[[Image:Henry_II_Arms_bw.png|75px]] or [[Image:Richard I of England Arms bw.png|75px]]</center>||1189–1198||Two possible interpretations of the arms shown on Richard I's first [[Great Seal of the Realm|Great Seal of England]]. The tinctures and the number of charges are |

| <center>[[Image:Henry_II_Arms_bw.png|75px]] or [[Image:Richard I of England Arms bw.png|75px]]</center>||1189–1198||Two possible interpretations of the arms shown on Richard I's first [[Great Seal of the Realm|Great Seal of England]], depicted in half-view. The tinctures and the number of charges are unknown.<ref name=Blazon01/> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[File:Royal Arms of England (1198-1340).svg|75px|center]]||1198–1340<br/>1360–1369||The arms on the second Great Seal of King Richard I, used by his successors until 1340: three golden lions ''[[Attitude (heraldry)#Passant|passant guardant]]'', on a red field.<ref name=Blazon01/><ref name="Boutell"/> |

| [[File:Royal Arms of England (1198-1340).svg|75px|center]]||1198–1340<br/>1360–1369||The arms on the second Great Seal of King Richard I, used without additions by his successors until 1340: ''Gules, three lions passant guardant in pale or'' (three golden lions ''[[Attitude (heraldry)#Passant|passant guardant]]'', on a red field).<ref name=Blazon01/><ref name="Boutell"/> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[File:Royal Arms of England (1340-1367).svg|75px|center]]||1340–1360</br>1369–1395</br>1399–1406||[[Edward III of England|King Edward III]] quartered |

| [[File:Royal Arms of England (1340-1367).svg|75px|center]]||1340–1360</br>1369–1395</br>1399–1406||In 1340 [[Edward III of England|King Edward III]](1327-1377) [[Quartering (heraldry)|quartered]] his paternal arms of Plantagenet with the [[National emblem of France|Royal Arms of France]]: ''[[Azure]] [[Fleur-de-lis|semé-de-lis]] [[Or (heraldry)|or]]'' (a scattering of gold [[fleurs-de-lis]] on a blue field), known as "France Ancient" which action symbolised his [[English claims to the French throne|claim to the French throne]].<ref name="Boutell"/><ref name=knight/> He placed the arms of France in the 1st & 4th quarters, the positions of greatest honour, symbolising the quasi-[[Feudalism|feudal]] superiority of the French king over his own family, descended from French counts who were technically [[vassal]]s of the kings of France. Summary blazon: ''France Ancient quartered with England'' |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[File:Royal Arms of England (1395-1399).svg|75px|center]]||1395–1399||[[Richard II of England|King Richard II]] impaled the Royal Arms of England with the [[attributed arms]] of King [[Edward the Confessor]] |

| [[File:Royal Arms of England (1395-1399).svg|75px|center]]||1395–1399||[[Richard II of England|King Richard II]] [[Impalement (heraldry)|impaled]] the Royal Arms of England with the [[attributed arms]] of King [[Edward the Confessor]],<ref name="Boutell"/><ref name=knight/> to symbolise his claimed mystical union with that ancient king and saint. The arms of the Confessor are placed in the [[Dexter and sinister|dexter]] half, the position of greatest honour. |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[File:Royal Arms of England (1399-1603).svg|75px|center]]||1406–1422||[[Henry IV of England|King Henry IV]], |

| [[File:Royal Arms of England (1399-1603).svg|75px|center]]||1406–1422||Between 1406 and 1411 [[Henry IV of England|King Henry IV]](1399-1413), in imitation of [[Charles VI of France]]'s 1376 alteration of the French arms to "[[National emblem of France|France Modern]]", reduced the number of fleurs-de-lis quartered in his own arms to three.<ref name="Boutell"/><ref name=knight/>Summary blazon: ''France Modern quartered with England'' |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[File:Royal Arms of England (1470-1471).svg|75px|center]]||1422–1461</br>1470–1471||[[Henry VI of England|King Henry VI]] |

| [[File:Royal Arms of England (1470-1471).svg|75px|center]]||1422–1461</br>1470–1471||[[Henry VI of England|King Henry VI]](1422-1461) used the heraldic technique of [[Impalement (heraldry)|impalement]], generally used to [[Marshalling (heraldry)|marshall]] the arms of husband and wife, to symbolise the [[dual monarchy of England and France]].<ref name=knight/>Blazon: France Modern [[Impalement(heraldry)|impaled]] with England'' |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[File:Royal Arms of England (1399-1603).svg|75px|center]]||1461–1470</br>1471–1554||[[Edward IV of England|King Edward IV]] restored the arms of King Henry IV.<ref name=knight/> |

| [[File:Royal Arms of England (1399-1603).svg|75px|center]]||1461–1470</br>1471–1554||[[Edward IV of England|King Edward IV]](1461-1483), who had deposed his predecessor, restored the arms of King Henry IV.<ref name=knight/> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[File:Royal Arms of England (1554-1558).svg|75px|center]]||1554–1558||[[Mary I of England|Queen Mary I]] impaled her arms with those of her husband, [[Philip II of Spain|King Philip]].<ref name="Boutell"/><ref name=knight/> Although Queen Mary I's father, [[Henry VIII of England|King Henry VIII]], assumed the title of [[King of Ireland]] and this was further conferred upon King Philip, the arms were not altered to feature the [[Kingdom of Ireland]]. |

| [[File:Royal Arms of England (1554-1558).svg|75px|center]]||1554–1558||[[Mary I of England|Queen Mary I]] [[Impalement (heraldry)|impaled]] her arms with those of her husband, [[Philip II of Spain|King Philip]].<ref name="Boutell"/><ref name=knight/> Although Queen Mary I's father, [[Henry VIII of England|King Henry VIII]], assumed the title of [[King of Ireland]] and this was further conferred upon King Philip, the arms were not altered to feature the [[Kingdom of Ireland]]. |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[File:Royal Arms of England (1399-1603).svg|75px|center]]||1558–1603||[[Elizabeth I of England|Queen Elizabeth I]] restored the arms of King Henry IV.<ref name="Boutell"/> |

| [[File:Royal Arms of England (1399-1603).svg|75px|center]]||1558–1603||[[Elizabeth I of England|Queen Elizabeth I]] restored the arms of King Henry IV.<ref name="Boutell"/> |

||

| Line 84: | Line 93: | ||

{{main|Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom}} |

{{main|Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom}} |

||

{{see also|Union of the Crowns|Commonwealth of England|Acts of Union 1707|Acts of Union 1800}} |

{{see also|Union of the Crowns|Commonwealth of England|Acts of Union 1707|Acts of Union 1800}} |

||

[[File:Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom.svg|thumb|right|upright|The [[Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom]] as used by Queen Elizabeth II from 1953 contains that of England as a [[quarter (heraldry)|quarter]]]] |

|||

On 1 May 1707, the kingdoms of England and Scotland were merged to form that of Great Britain; this was reflected by impaling their arms in a single quarter. The claim to the French throne continued, albeit passively, until it was mooted by the [[French Revolution]] and the formation of the [[French First Republic]] in 1792.<ref name=Blazon01/> During the peace negotiations at the Conference of Lille, from July to November 1797, the French delegates demanded that the King of Great Britain abandon the title of King of France as a condition of peace. The [[Acts of Union 1800]] united the [[Kingdom of Great Britain]] with the [[Kingdom of Ireland]] to form the [[United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland]]. Under King [[George III of the United Kingdom]], a proclamation of 1 January 1801 set the [[Style of the British sovereign|royal style and titles]] and modified the Royal Arms, removing the French quarter and putting the arms of England, Scotland and Ireland on the same structural level, with the dynastic arms of Hanover moved to an [[inescutcheon]].<ref name=Blazon01/> |

On 1 May 1707, the kingdoms of England and Scotland were merged to form that of Great Britain; this was reflected by impaling their arms in a single quarter. The claim to the French throne continued, albeit passively, until it was mooted by the [[French Revolution]] and the formation of the [[French First Republic]] in 1792.<ref name=Blazon01/> During the peace negotiations at the Conference of Lille, from July to November 1797, the French delegates demanded that the King of Great Britain abandon the title of King of France as a condition of peace. The [[Acts of Union 1800]] united the [[Kingdom of Great Britain]] with the [[Kingdom of Ireland]] to form the [[United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland]]. Under King [[George III of the United Kingdom]], a proclamation of 1 January 1801 set the [[Style of the British sovereign|royal style and titles]] and modified the Royal Arms, removing the French quarter and putting the arms of England, Scotland and Ireland on the same structural level, with the dynastic arms of Hanover moved to an [[inescutcheon]].<ref name=Blazon01/> |

||

Revision as of 22:28, 7 December 2011

| Royal Arms of England | |

|---|---|

| |

| Versions | |

The Royal Banner of England | |

Royal Coat of Arms of England (1399–1603) | |

| Armiger | Monarchs of England |

| Adopted | High Middle Ages (with various modifications) |

| Shield | Gules three lions passant guardant in pale Or armed and langued Azure. |

| Supporters | Various |

| Motto | Dieu et mon droit |

| Order(s) | Order of the Garter |

| Earlier version(s) |  or or  |

| Use | National symbol of England |

In heraldry, the Royal Arms of England[2] is a coat of arms used exclusively by the English monarch. It forms an expression and symbol of royal power, exercised (now democratically) by Her Majesty's Government, and is thus displayed prominently within government buildings and within courts dispensing royal justice, on the letter-heads of the Inland Revenue, a branch of Her Majesty's Treasury and in other such contexts. More widely the Royal Arms may be seen to symbolise the nation of the United Kingdom of England, Scotland and Northern Ireland, which nation is however more properly signified by the national emblem of the Union Flag. [3] The earliest constituent of the current quartered arms is the "Lions of Plantagenet". This is blazoned (technical heraldic description) as: Gules, three lions passant guardant in pale or armed and langued azure,[4][5] signifying three identical gold lions with blue tongues and claws, in the act of walking past, but with head facing toward, the observer, arranged one above the other in a column on a red field (i.e. background). These arms when incorporated into quarterings of other families, for example of royal dukes, may be correctly blazoned simply as "England". These arms of Plantagenet were adopted in simple and primitive form, as a single lion or a pair, after the accession of King Henry II(1154-1189), son of Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou, and became fixed in their present triple form and tinctures during the reign of his son and heir Richard I(1189-1199). The first use of heraldic arms spread rapidly to the nobility and knights from about 1200 to 1215. The arms of Plantagenet have been variously quartered by English monarchs with the royal arms of France, Scotland, Ireland, the House of Nassau and Kingdom of Hanover, according to dynastic and other political alliances and marriages entered into by English monarchs.

Although royal emblems depicting lions were used by the Norman dynasty,[6][7][8] as can be seen on certain shields in the Bayeux Tapestry(1066), a formal and consistent system of English heraldry emerged during the very early 13th century. The escutcheon, or shield, featuring three lions is traceable back to King Richard I's Great Seal of the Realm, which initially used a single lion rampant, or a pair of lions, but in 1198, was permanently altered to depict three lions passant.[5][6][7][8] In 1340, King Edward III laid claim to the throne of France and quartered his paternal arms of Plantagenet with those of the King of France.[6] This quartering was adjusted, abandoned and restored intermittently throughout the Middle Ages as the relationship between England and France changed. Since the Union of the Crowns in 1603, when the kingdoms of England and Scotland entered a union, which in substance was a feudal personal union between the two monarchs, the English king added to his arms a quartering of the arms of the king of Scotland to form the large part of what has now become the arms of the monarch of the United Kingdom, termed popularly the Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom, although strictly they are personal family arms of the monarch.[9] "The Lions of England" appear in a similar capacity to represent England in the Arms of Canada and the Queen's Personal Canadian Flag.[10] The coat of three lions continues to represent England on several coins of the pound sterling, forms the basis, with altered tinctures, of several emblems of English national sports teams, [11][12] and endures as one of the most recognisable national symbols of England.[3]

The Royal Arms in the form of a heraldic flag signifies the presence of the monarch in person within the building or vehicle from which it flies. It is variously known as the Royal Banner of England,[13] the Banner of the Royal Arms,[14] the Banner of the King of England,[15][16] or by the misnomer of the Royal Standard of England.[note 1] This Royal Banner differs entirely from England's national flag, St George's Cross, in that it does not represent any particular area or land, but rather symbolises the monarch herself. It is essentially the remnant of feudal usage, to inform as to the physical presence of a great lord, and such personal banners are still used by many of the great and ancient English ducal families in a similar manner, for example they are flown from a flagstaff on the duke's home when he is in residence and removed when he has departed [4]

History

Origins

Lions had previously been used by the Norman dynasty as royal emblems, and imaginary arms, known as attributed arms, have been allocated by their descendants to kings who pre-dated the introduction of hereditary English heraldry which spread into general usage in the very early 13th.c.[6] King Henry II(1154-1189), son of Geoffrey Plantagenet, used used a shield with two lions on it,[18] an apparent variation on the usage of his father, as appears from a half-view of his shield on his seal. His two sons experimented with different combinations of lions. The battle-shield of Richard the Lionheart, in half-view, shows a single lion rampant, or perhaps two lions affrontés, as depicted on his first seal,[5] but his later shield showed three lions passant guardant as depicted on his 1198 Great Seal of England, and thus established the lasting design of the Royal Arms of England.[5][18] Although in 1177 his younger brother the future King John(1199-1216) used a seal showing a shield with two lions passant guardant, the three golden lions passant guardant on a red field were used as the Royal Arms by John after he had become king in 1199 and by his son Henry III(1216-1272) and by future kings until Edward III(1327-1377),[5] who in 1340 quartered them with the arms of the King of France, with the arms of France placed in the quarters of greatest honour, as arms of pretence, as a symbol of his claim to the French throne.

Crest

In 1362, Edward III, one of whose titles was Lord of Aquitaine, used the arms of the Counts of Aquitaine as his crest, and made his eldest son Edward the Black Prince Prince of Aquitaine. In 1390, The Black Prince's son King King Richard II appointed his uncle John of Gaunt as Duke of Aquitaine. This title again passed on to Henry IV (1399), who inherited the duchy from his father, but ceded it to his son upon becoming King of England. Henry V continued to rule over Aquitaine as King of England and Lord of Aquitaine. The Lion of Aquitaine has remained the Royal Crest of England since the reign of Edward III.

Development

In 1340, following the death of King Charles IV of France, Edward III asserted a claim to the French throne through his mother Isabella of France. In addition to initiating the Hundred Years' War, Edward III expressed his claim in heraldic form by adopting "arms of pretence" by quartering the royal arms of England with the Arms of France (France Ancien), and furthermore placed the French arms in the 1st & 4th quarters of greatest honour, generally reserved for the paternal arms, as a recognition of quasi-feudal superiority of the King of France. This quartering continued until 1801, with intervals in 1360–1369 and 1420–1422.[5]

Following the death of Queen Elizabeth I of England in 1603, the throne of England was inherited by the Scottish House of Stuart, resulting in the Union of the Crowns: the Kingdom of England and Kingdom of Scotland were united in a personal union under King James I of England and VI of Scotland.[19] As a consequence, the Royal Arms of England and Scotland were combined in the king's new personal arms. Nevertheless, although referencing the personal union with Scotland and Ireland, the Royal Arms of England remained distinct from the Royal Arms of Scotland, until the two realms were joined in a political union in 1707, leading to a unified Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom.[9]

| Escutcheon | Period | Description |

|---|---|---|

|

1154–1189 | King Henry II, the first king from the House of Plantagenet, is thought to have used pair of lions passant in his personal arms. Although the tinctures of Henry's coat are unknown, some descendants used a similar coat with gold lions on red.[18] These arms were later allocated as attributed arms to William the Conquerer. |

or or  |

1189–1198 | Two possible interpretations of the arms shown on Richard I's first Great Seal of England, depicted in half-view. The tinctures and the number of charges are unknown.[5] |

|

1198–1340 1360–1369 |

The arms on the second Great Seal of King Richard I, used without additions by his successors until 1340: Gules, three lions passant guardant in pale or (three golden lions passant guardant, on a red field).[5][6] |

|

1340–1360 1369–1395 1399–1406 |

In 1340 King Edward III(1327-1377) quartered his paternal arms of Plantagenet with the Royal Arms of France: Azure semé-de-lis or (a scattering of gold fleurs-de-lis on a blue field), known as "France Ancient" which action symbolised his claim to the French throne.[6][20] He placed the arms of France in the 1st & 4th quarters, the positions of greatest honour, symbolising the quasi-feudal superiority of the French king over his own family, descended from French counts who were technically vassals of the kings of France. Summary blazon: France Ancient quartered with England |

|

1395–1399 | King Richard II impaled the Royal Arms of England with the attributed arms of King Edward the Confessor,[6][20] to symbolise his claimed mystical union with that ancient king and saint. The arms of the Confessor are placed in the dexter half, the position of greatest honour. |

|

1406–1422 | Between 1406 and 1411 King Henry IV(1399-1413), in imitation of Charles VI of France's 1376 alteration of the French arms to "France Modern", reduced the number of fleurs-de-lis quartered in his own arms to three.[6][20]Summary blazon: France Modern quartered with England |

|

1422–1461 1470–1471 |

King Henry VI(1422-1461) used the heraldic technique of impalement, generally used to marshall the arms of husband and wife, to symbolise the dual monarchy of England and France.[20]Blazon: France Modern impaled with England |

|

1461–1470 1471–1554 |

King Edward IV(1461-1483), who had deposed his predecessor, restored the arms of King Henry IV.[20] |

|

1554–1558 | Queen Mary I impaled her arms with those of her husband, King Philip.[6][20] Although Queen Mary I's father, King Henry VIII, assumed the title of King of Ireland and this was further conferred upon King Philip, the arms were not altered to feature the Kingdom of Ireland. |

|

1558–1603 | Queen Elizabeth I restored the arms of King Henry IV.[6] |

|

1603–1649 1660-1689 | James VI, King of Scots inherited the English and Irish thrones in 1603 in the Union of the Crowns, and quartered the Royal Arms of England with those of Scotland. The Royal Arms of Ireland was added to represent the Kingdom of Ireland. Last used by Queen Anne, this was the final version of the Royal Arms of England before being subsumed into the Royal Arms of Great Britain.[6][20] |

|

1689-1694 | King James II is deposed and replaced with his daughter Mary and her husband, William, Prince of Orange ruling jointly as William III & II and Mary II. As King and Queen Regnant they impaled their arms: William bore the Royal Arms with an escutcheon of Nassau (the royal house to which William belonged) added (a golden lion rampant on a blue field), while Mary bore the Royal Arms undifferenced.[21] |

|

1694-1702 | After the death of Mary II, William III reigned alone, and used his arms only.[6] |

|

1702-1707 | Queen Anne inherited the throne upon the death of King William III & II, and the Royal Arms returned to the 1603 version.[6] |

Union with Scotland and Ireland

On 1 May 1707, the kingdoms of England and Scotland were merged to form that of Great Britain; this was reflected by impaling their arms in a single quarter. The claim to the French throne continued, albeit passively, until it was mooted by the French Revolution and the formation of the French First Republic in 1792.[5] During the peace negotiations at the Conference of Lille, from July to November 1797, the French delegates demanded that the King of Great Britain abandon the title of King of France as a condition of peace. The Acts of Union 1800 united the Kingdom of Great Britain with the Kingdom of Ireland to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Under King George III of the United Kingdom, a proclamation of 1 January 1801 set the royal style and titles and modified the Royal Arms, removing the French quarter and putting the arms of England, Scotland and Ireland on the same structural level, with the dynastic arms of Hanover moved to an inescutcheon.[5]

Contemporary

English heraldry flourished as a working art up to around the 17th century, when it assumed a mainly ceremonial role.[5] The Royal Arms of England continued to embody information relating to English history.[5] Although the Acts of Union 1707 placed England within the Kingdom of Great Britain, prompting new, British Royal Arms, the Royal Arms of England has continued to endure as one of the national symbols of England,[3] and has a variety of active uses. For instance, the coats of arms of both The Football Association[11][22] and the England and Wales Cricket Board[23] have a design featuring three lions passant, based on the historic Royal Arms of England. In 1997 (and again in 2002), the Royal Mint issued a British one pound (£1) coin featuring three lions passant to represent England.[24] To celebrate St George's Day, in 2001, Royal Mail issued first– and second-class postage stamps with the Royal Crest of England (a crowned lion), and the Royal Arms of England (three lions passant) respectively.[25]

-

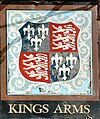

The Royal Arms of England as depicted on the Kings Arms pub in Blakeney, Norfolk

-

A British one pound (£1) coin, issued in 1997, featuring three lions passant, representing England.[24]

-

A modern, commercially available Royal Banner of England, printed on polyester fabric

-

The coat of arms of the Football Association (granted by the College of Arms in 1949), worn by the England national football team, are based on the Royal Arms of England.[11][12]

Crest, supporters and other parts of the achievement

Various accessories to the escutcheon (shield) were added and modified by successive English monarchs. These included a crest (with mantling, helm and crown); supporters (with a compartment); a motto; and the insignia of an order of knighthood. These various components made up the full achievement of arms.[20]

Royal crest

The first addition to the shield was in the form of a crest borne above the shield. It was during the reign of Edward III that the crest began to be widely used in English heraldry. The first representation of a royal crest was in Edward's third Great Seal, which showed a helm above the arms, and thereon a gold lion passant guardant standing upon a chapeau, and bearing a royal crown on its head.[26] The design underwent minor variations until it took on its present form in the reign of Henry VIII: "The Royal Crown proper, thereon a lion statant guardant Or, royally crowned also proper".[26]

The exact form of crown used in the crest varied over time. Until the reign of Henry VI it was usually shown as an open circlet adorned with fleurs-de-lys or stylised leaves. On Henry's first seal for foreign affairs the design was altered with the circlet decorated by alternating crosses formy and fleurs-de-lys. From the reign of Edward IV the crown bore a single arch, altered to a double arch by Henry VII. The design varied in details until the late 17th century, but since that time has consisted of a jewelled circlet, above which are alternating crosses formy and fleurs-de-lys. From this spring two arches decorated with pearls, and at their intersection an orb surmounted by a cross formy.[26] A cap of crimson velvet is shown within the crown, with the cap's ermine lining appearing at the base of the crown in lieu of a torse.[26] The shape of the arches of the crown has been represented differently at different times, and can help to date a depiction of the crest.[26]

The helm on which the crest was borne was originally a simple steel design, sometimes with gold embellishments. In the reign of Elizabeth I a pattern of helm unique to the Royal Arms was introduced. This is a gold helm with a barred visor, facing the viewer.[27] The decorative mantling (a stylised cloth cloak that hangs from the helm) was originally of red cloth lined with ermine, but was altered to cloth of gold lined ermine by Elizabeth.[27]

Supporters

Animal supporters, standing on either side of the shield to hold and guard it, first appeared in English heraldry in the 15th century. Originally, they were not regarded as an integral part of arms, and were subject to frequent change. Various animals were sporadically shown supporting the Royal Arms of England, but it was only with the reign of Edward IV that their use became consistent. Supporters fell under the regulation of the Kings of Arms in the Tudor period. The heralds of that time also prochronistically created supporters for earlier monarchs, and although these attributed supporters were never used by the monarchs concerned, they were later used to signify them on public buildings or monuments completed after their deaths, for instance at St. George's Chapel, in Windsor Castle.[28][29]

The boar adopted by Richard III prompted William Collingbourne's quip "The Rat, the Cat, and Lovell the Dog, Rule all England under the Hog",[note 2][20] and William Shakespeare's derision in Richard III.[note 3][30] The red dragon, a symbol of the Tudor dynasty, was added upon the accession of the Henry VII.[20] After the Union of the Crowns, the supporters of the arms of the British monarch have remained as the Lion and the Unicorn, representing England and Scotland respectively.[20]

| Period | Description |

|---|---|

| Edward III

(1327–1377) |

Lion and falcon (attributed); Two lions; two angels |

| Richard II

(1377–1399) |

Two white harts (attributed) |

| Henry IV

(1399–1413) |

Lion and antelope; antelope and swan (attributed); Two angels |

| Henry V

(1413–1422) |

Lion and antelope (attributed) |

| Henry VI

(1422–1461) |

Two antelopes argent; lion and panther; antelope and tiger (attributed) |

| Edward IV

(1461–1483) |

Lion or and bull sable; lion argent and hart argent; two lions argent |

| Edward V

(1483) |

Lion argent and hart argent, gorged and chained or |

| Richard III

(1483–1485) |

Lion or and boar argent; two boars argent; boar argent and bull sable |

| Henry VII

(1485–1509) |

Dragon gules and greyhound argent; two greyhounds argent; lion or and dragon gules |

| Henry VIII

(1509–1547) |

Lion or and dragon gules; dragon gules and bull sable; dragon gules and greyhound argent; dragon gules and cock argent |

| Edward VI

(1547–1553) |

Lion or and dragon gules |

| Mary I

(1553–1558) |

Lion or and dragon gules; lion or and greyhound argent; eagle sable and lion or (Philip and Mary) |

| Elizabeth I

(1558–1603) |

Lion or and dragon or; lion or and greyhound argent |

| James I

From 1603 |

Lion gardant or, regally crowned proper and unicorn argent, armed unguled, and crined or, gorged with a coronet composed of crosses paty and fleurs-de-lis or, a chain affixed thereto passing between the forelegs and reflexing over the back or |

Garter and motto

Edward III founded the Order of the Garter in about 1348. Since then, the full achievement of the Royal Arms has included a representation of the Garter, encircling the shield. This is a blue circlet with gold buckle and edging, bearing the order's Old French motto Honi soit qui mal y pense ("evil to him who evil thinks") in gold capital letters.[27]

A motto, placed on a scroll below the Royal Arms of England, seems to have first been adopted by Henry IV in the early 15th century. His motto was Souverayne ("sovereign").[27] His son, Henry V adopted the motto Dieu et mon droit ("God and my right"). While this motto has been exclusively used since the accession of George I in 1714, and continues to form part of the Royal Arms of the United Kingdom, other mottoes were used by certain monarchs in the intervening period.[27] Veritas temporis filia ("truth is the daughter of time") was the motto of Mary I (1553–1558), Semper Eadem ("always the same") was used by Elizabeth I (1558–1603) and Anne (1702–1714), James I (1603–1625) sometimes used Beati pacifici ("blessed are the peacemakers"), while William III (1689–1702) used the motto of the House of Orange: Je maintiendrai ("I will maintain").[27]

As a banner

The Royal Banner of England is the English banner of arms and so has always borne the Royal Arms of England—the personal arms of England's reigning monarch. When displayed in war or battle, this banner signalled that the sovereign was present in person.[17] Because the Royal Banner depicted the Royal Arms of England, so its design and composition changed throughout the Middle Ages.[17] It is variously known as the Royal Banner of England, the Banner of the Royal Arms,[14] the Banner of the King of England, or by the misnomer of the Royal Standard of England; Arthur Charles Fox-Davies explains that it is "a misnomer to term the banner of the Royal Arms the Royal Standard", because "the term standard properly refers to the long tapering flag used in battle, by which an overlord mustered his retainers in battle".[14] The archaeologist and antiquarian Charles Boutell also makes this distinction.[17] This Royal Banner differs from England's national flag, St George's Cross, in that it does not represent any particular area or land, but rather symbolises the sovereignty vested in the rulers thereof.[4]

When displayed in war or battle, this banner signalled that the sovereign was present in person.[17] Because the Royal Banner depicted the Royal Arms of England, so its design and composition changed throughout the Middle Ages.[17]

In other banners

-

The Banner of the Duchy of Lancaster viz the Royal Banner of England defaced with a blue label of three points, each point containing three fleur-de-lis.

-

The Royal Banner of the United Kingdom featuring the Royal Banner of England in the first and fourth quarters.

-

The Royal Banner of the United Kingdom used in Scotland, featuring the Royal Banner of England in the second quarter.

-

The Queen's Personal Canadian Flag, featuring the Royal Banner of England in the First quarter of the first two divisions.

Other roles and manifestations

Several ancient English towns displayed the Royal Arms of England upon their seals and, when it occurred to them to adopt insignia of their own, used the Royal Arms, albeit with modification, as their inspiration.[33] For instance, in the arms of New Romney, the field is changed from red to blue.[33] Hereford changes the lions from gold to silver, and in the 17th century was granted a blue border charged with silver saltires in allusion to its siege by a Scottish army during the English Civil War.[33] The town council of Faversham changes only the hindquarters of the three lions to silver.[32] Berkshire County Council bore arms with two golden lions in reference to its Royal patronage and the Norman kings' influence upon the early history of Berkshire.[33]

The Royal Arms of England features on the tabard, the distinctive traditional garment of English officers of arms.[34] These garments were worn by heralds when performing their original duties—making royal or state proclamations and announcing tournaments. Since 1484 they have been part of the Royal Household.[35] Tabards featuring the Royal Arms continue to be worn at several traditional ceremonies, such as the annual procession and service of the Order of the Garter at Windsor Castle, the State Opening of Parliament at the Palace of Westminster, the coronation of the British monarch at Westminster Abbey, and state funerals in the United Kingdom.[34]

-

Thomas Hawley, an English officer of arms, wearing a tabard emblazoned with the Royal Arms of England

-

The Arms of the Gibraltarian Government, which was granted by the College of Arms in 1836 to commemorate the Great Siege of Gibraltar, features the Royal Arms of England.[36]

-

Edward, the Black Prince, wearing a surcoat emblazoned with the Royal Arms of England

-

The arms of Oriel College, Oxford alludes to the institution's regal foundation by using the Royal Arms of England with a silver border added for difference.[37]

See also

Notes

- ^ In A Complete Guide to Heraldry (1909), Arthur Charles Fox-Davies explains:

The archaeologist and antiquarian Charles Boutell also makes this distinction.[17]It is a misnomer to term the banner of the Royal Arms the Royal Standard. The term standard properly refers to the long tapering flag used in battle, by which an overlord mustered his retainers in battle.[14]

- ^ This was a pun on Richard III (the Hog) and three of his staunchest supporters, Richard Ratcliffe (the Rat), William Catesby (the Cat) and Francis Lovell (the Dog).

- ^ For instance, in Act 1, Scene III of Richard III, Margaret, Queen consort of England describes Richard as "Thou elvish-mark'd, abortive, rooting hog!"

References

- ^ Debrett's Peerage, 1968, p.2

- ^ Jamieson 1998, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b c Boutell 1859, p. 373: "The three golden lions upon a ground of red have certainly continued to be the royal and national arms of England."

- ^ a b c Fox-Davies 2008, p. 607.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l The First Foot Guards. "Coat of Arms of King George III". footguards.tripod.com. Retrieved 4-February-2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Brooke-Little 1950, pp. 205–222.

- ^ a b Brooke-Little 1981, p. 3–6

- ^ a b Paston-Bedingfield & Gwynn-Jones 1993, pp. 114–115.

- ^ a b The Royal Household. "Union Jack". royal.gov.uk. Retrieved 2009-08-28.

- ^ The Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada. "The Flag of Her Majesty the Queen for personal use in Canada". gg.ca. Retrieved 2009-08-28.

- ^ a b c Briggs 1971, pp. 166–167.

- ^ a b Ingle, Sean (2002-07-18). "Why do England have three lions on their shirts?". guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-09-15.

- ^ Thompson 2001, p. 91.

- ^ a b c d Fox-Davies 1909, p. 474.

- ^ Keightley 1834, p. 310.

- ^ James 2009, p. 247.

- ^ a b c d e f Boutell 1859, pp. 373–377.

- ^ a b c Ailes, Adrian (1982). The Origins of The Royal Arms of England. Reading: Graduate Center for Medieval Studies, University of Reading. pp. 52–63.

- ^ Ross 2002, p. 56.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Knight 1835, pp. 148–150.

- ^ Arnaud Bunel's Héraldique européenne site

- ^ "England Football Online – The Three Lions". englandfootballonline.com. Retrieved 2010-09-15.

- ^ England Wales Cricket Board

- ^ a b Royal Mint (2010). "The United Kingdom £1 Coin". royalmint.com. Retrieved 2010-09-15.

- ^ "Three lions replace The Queen on stamps". telegraph.co.uk. 2001-03-06. Retrieved 2010-09-15.

- ^ a b c d e Brooke-Little 1981, pp. 4–8.

- ^ a b c d e f Brooke-Little 1981, p. 16.

- ^ Brooke-Little 1981, p. 9.

- ^ Paston-Bedingfield & Gwynn-Jones 1993, p. 117.

- ^ Hall 1853, p. 74.

- ^ Woodward 1997, pp. 50–54.

- ^ a b Faversham Town Council (2010). "Faversham Coat of Arms". The Faversham Website. faversham.org. Retrieved 2010-09-16.

- ^ a b c d e Scott-Giles 1953, p. 11.

- ^ a b College of Arms. "The history of the Royal heralds and the College of Arms". college-of-arms.gov.uk. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ "Herald's tabard". The Independent. independent.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ Sumner 2001, p. 9.

- ^ "The name and arms of the College". oriel.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

Bibliography

- Boutell, Charles (1859). "The Art Journal London". 5. Virtue: 373–376.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Briggs, Geoffrey (1971). Civic and Corporate Heraldry: A Dictionary of Impersonal Arms of England, Wales and N. Ireland. London: Heraldry Today. ISBN 0900455217.

- Brooke-Little, J.P., FSA (1978) [1950]. Boutell's Heraldry (Revised ed.). London: Frederick Warne LTD. ISBN 0-7232-2096-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Brooke-Little, J.P., FSA, MVO, MA, FSA, FHS (1981). Royal Heraldry. Beasts and Badges of Britain. Derby: Pilgrim Press Ltd. ISBN 0900594594.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles (2008) [1909]. A Complete Guide to Heraldry. READ.

- Hall, Samuel Carter (1853). The Book of British Ballads. H. G. Bohn.

- Hassler, Charles (1980). The Royal Arms. ISBN 0904041204.

- James, George Payne Rainsford (2009). The History of Chivalry. General Books LLC.

- Jamieson, Andrew Stewart (1998). Coats of Arms. Pitkin. ISBN 9-780853-728702.

- Knight, Charles (1835-04-18). "English Regal Arms and Supporters". The Penny Magazine. Vol. 4. Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge.

- Keightley, Thomas (1834). The crusaders; or, Scenes, events, and characters, from the times of the crusades. Vol. 2 (3rd ed.). J. W. Parker.

- Paston-Bedingfield, Henry; Gwynn-Jones, Peter (1993). Heraldry. Greenwich Editions. ISBN 0862882796.

- Robson, Thomas (1830). The British Herald. Turner & Marwood.

- Ross, David (2002). Chronology of Scottish History. Geddes & Grosset. ISBN 1855343800.

- Scott-Giles, Wilfrid (1953). Civic Heraldry of England and Wales (2nd ed.). London: J M Dent & Sons.

- Sumner, Ian (2001). British Colours & Standards 1747–1881 (2): Infantry. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1841762016.

- Thomson, D. Croal (2001). Fifty Years of Art, 1849–1899: Being Articles and Illustrations Selected from 'The Art Journal'. Adegi Graphics LLC.

- Woodward, Jennifer (1997). The Theatre of Death: The Ritual Management of Royal Funerals in Renaissance England, 1570–1625. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9780851157047.

![A British one pound (£1) coin, issued in 1997, featuring three lions passant, representing England.[24]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/b/bd/British_one_pound_coin_1997_Lions_Passant.jpg)

![The Arms of the Gibraltarian Government, which was granted by the College of Arms in 1836 to commemorate the Great Siege of Gibraltar, features the Royal Arms of England.[36]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/84/Coat_of_arms_of_the_Government_of_Gibraltar.svg/120px-Coat_of_arms_of_the_Government_of_Gibraltar.svg.png)

![The arms of Oriel College, Oxford alludes to the institution's regal foundation by using the Royal Arms of England with a silver border added for difference.[37]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/33/Oriel_Boss.jpg/120px-Oriel_Boss.jpg)