Erich von Manstein: Difference between revisions

m Spell atack => attack (224) |

→Trial: re-work content on trial, giving details of the charges and statements of the prosecution and defence |

||

| Line 192: | Line 192: | ||

Manstein was moved to [[Nuremberg]] in October 1945. He was held at the [[Palace of Justice (Nuremberg)|Palace of Justice]], the location of the [[Nuremberg Trials]] of major Nazi war criminals and organisations. While there, Manstein helped prepare a 132-page document for the defense of the General Staff and the OKW, on trial at Nuremberg in August 1946. The myth that the Wehrmacht was "clean"—not culpable for the events of the Holocaust—arose partly as a result of this document, written largely by Manstein, along with General of Cavalry Sigfried Westphal. He also gave oral testimony about the ''Einsatzgruppen'', the treatment of prisoners of war, and the concept of military obedience, especially as related to the [[Commissar Order]], an order issued by Hitler in 1941 requiring all Soviet [[political commissar]]s to be shot without trial. Manstein admitted that he received the order, but said he did not carry it out. He denied any knowledge of the activities of the ''Einsatzgruppen'', and testified that soldiers under his command were not involved in the murder of Jewish civilians. In September 1946 the General Staff and the OKW were declared to not be criminal organisations.{{sfn|Melvin|2010|pp=432–448}} |

Manstein was moved to [[Nuremberg]] in October 1945. He was held at the [[Palace of Justice (Nuremberg)|Palace of Justice]], the location of the [[Nuremberg Trials]] of major Nazi war criminals and organisations. While there, Manstein helped prepare a 132-page document for the defense of the General Staff and the OKW, on trial at Nuremberg in August 1946. The myth that the Wehrmacht was "clean"—not culpable for the events of the Holocaust—arose partly as a result of this document, written largely by Manstein, along with General of Cavalry Sigfried Westphal. He also gave oral testimony about the ''Einsatzgruppen'', the treatment of prisoners of war, and the concept of military obedience, especially as related to the [[Commissar Order]], an order issued by Hitler in 1941 requiring all Soviet [[political commissar]]s to be shot without trial. Manstein admitted that he received the order, but said he did not carry it out. He denied any knowledge of the activities of the ''Einsatzgruppen'', and testified that soldiers under his command were not involved in the murder of Jewish civilians. In September 1946 the General Staff and the OKW were declared to not be criminal organisations.{{sfn|Melvin|2010|pp=432–448}} |

||

After his testimony at Nuremberg, Manstein was interned by the British as a prisoner of war at [[Island Farm]] (also known as Special Camp 11) in [[Bridgend]], [[Wales]], where he awaited the decision as to whether or not he would face a war crimes trial. He mostly kept apart from the other inmates, taking solitary walks, tending a small garden, and beginning work on the drafts of two books. British author [[B. H. Liddell Hart]] was in correspondence with Manstein and others at Island Farm and visited inmates of several camps around Britain while preparing his best-selling 1947 book ''On the Other Side of the Hill''. Liddell Hart was an admirer of the German generals; he described Manstein as an operational genius. The two remained in contact, and Liddell Hart later helped Manstein arrange the publication of the Engish edition of his memoir, ''[[Verlorene Siege]]'' (''Lost Victories''), in 1958.{{sfn|Smelser|Davies|2008|p=102}}{{sfn|Melvin|2010|pp=452–456}} |

After his testimony at Nuremberg, Manstein was interned by the British as a prisoner of war at [[Island Farm]] (also known as Special Camp 11) in [[Bridgend]], [[Wales]], where he awaited the decision as to whether or not he would face a war crimes trial. He mostly kept apart from the other inmates, taking solitary walks, tending a small garden, and beginning work on the drafts of two books. British author [[B. H. Liddell Hart]] was in correspondence with Manstein and others at Island Farm and visited inmates of several camps around Britain while preparing his best-selling 1947 book ''On the Other Side of the Hill''. Liddell Hart was an admirer of the German generals; he described Manstein as an operational genius. The two remained in contact, and Liddell Hart later helped Manstein arrange the publication of the Engish edition of his memoir, ''[[Verlorene Siege]]'' (''Lost Victories''), in 1958.{{sfn|Smelser|Davies|2008|p=102}}{{sfn|Melvin|2010|pp=452–456}} The British cabinet, under pressure from the Soviet Union, finally decided in July 1948 to prosecute Manstein for war crimes. He and three other senior officers ([[Walther von Brauchitsch]], Gerd von Rundstedt, and [[Adolf Strauss]]) were transferred to [[Munster Training Area|Munsterlager]] to await trial. Brauchitsch died that October, and Rundstend and Strauss were released on medical grounds in March 1949. Manstein's trial was held in Hamburg from 23 August to 19 December 1949.{{sfn|Melvin|2010|pp=460–463, 467}} |

||

Manstein faced seventeen charges at the trial, three of which pertained to events in Poland and fourteen regarding events in the Soviet Union. The first and second charges regarding Poland accused him of authorising the killing, deportation, and maltreatment of Jews and other Polish civilians, and failing to prevent such killings and maltreatment. The third charge covered maltreatment and killing of Polish prisoners of war. The charges regarding events in the Soviet Union included the fourth charge, failing to attend to the needs of Soviet prisoners of war; many died through maltreatment or were executed by the ''[[Sicherheitsdienst]]'' (SD). The fifth charge regarded an order issued by Manstein on 20 September 1941 whereby captured Soviet soldiers were summarily killed without trial. The sixth charge claimed that captured Soviet soldiers were illegally recruited into German armed forces units. The seventh charge claimed that Soviet prisoners of war were illegally compelled to do dangerous work, and work of a military nature, which is prohibited by the [[Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907|Hague Convention]]. The eighth charge included fifteen cases of Soviet political commissars being executed in compliance with Hitler's Commissar Order.{{sfn|Melvin|2010|pp=469–471}} |

|||

In court, Manstein's defence, led by the prominent lawyer [[Reginald Thomas Paget]], argued that he had been unaware that [[genocide]] was taking place in the territory under his control. It was argued that Manstein did not enforce the "[[Commissar order]]", which called for the immediate execution of [[Political commissar#Red Army|Red Army Communist Party commissars]]. According to his testimony at the Nuremberg Trials,<ref name=Nuremburg08-10-46-608>[http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/08-10-46.asp Nuremberg trials proceedings, Vol. 20, pp. 608–609, August 10, 1946]</ref> he received it, but refused to carry it out. He claimed that his superior at the time, Field Marshal [[Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb|von Leeb]], tolerated and tacitly approved of his choice, and he also claimed that the order was not carried out in practice. In fact, Manstein had perjured himself when he claimed that he did not enforce the "Commissar Order": documents from 1941 showed that he passed the order on to his subordinates, and that he had suspected commissars shot.{{sfn|Smelser|Davies|2008|p=97}} Paget claimed that the only commissars Manstein had had shot were in the rear area in the Crimea by police units, likely because of partisan activities.{{sfn|Paget|1952|p=230}} |

|||

The remaining charges were related to the activities of ''Einsatzgruppe'' D in the Crimea. The ninth charge accused Manstein of authorising the execution of Jews and other Soviet citizens. The tenth charge accused him of failing to protect the lives of the civilians in the area. The eleventh charge claimed that soldiers in units commanded by Manstein handed over civilians to the ''Einstatsgruppe'', while knowing that to do so would mean their deaths. The twelfth charge accused Manstein of authorising his troops to kill Jewish civilians in the Crimea. The thirteenth charge accused Manstein of authorising the killing of civilians for offences which they did not commit. The fourteenth charge accused Manstein of issuing orders to execute civilians without trial; for merely being suspects; and for having committed offences that did not warrant the death penalty. The fifteenth charge was that Soviet citizens, in violation of the Hague Convention, had been compelled to build defensive positions and dig trenches in combat areas. The sixteenth charge accused him of ordering the deportation of civilians as slave labourers. The final charge accused Manstein of issuing "scorched earth" orders while in retreat, while ordering the deportation of the civilians in the affected areas. The fourteenth and fifteenth charges were withdrawn before the trial for lack of supporting evidence.{{sfn|Melvin|2010|pp=471–473}} |

|||

Manstein issued an order on 20 November 1941: his version of Field Marshal [[Walther von Reichenau|von Reichenau's]] infamous "[[Severity Order]]"<ref>[http://www.ns-archiv.de/krieg/untermenschen/reichenau.shtml "Der Reichenau-Befehl, Das Verhalten der Truppe im Ostraum"]</ref> of 10 October 1941, which equated "partisans" with "Jews" and called for their extermination. Following complaints by some of his officers about the massacres being committed by ''[[Einsatzgruppen]]'', Reicheanu had issued the "Severity Order" to explain to his men why in his view the massacres were necessary. Field Marshal [[Gerd von Rundstedt]], the commander of Army Group South and Reicheanu's superior, expressed his "complete agreement" with it, and send out a circular to all of his generals suggesting that they issue their own versions of the "Severity Order".<ref>Mayer, Arno J. ''Why Did The Heavens Not Darken?'', New York: Pantheon, 1988, 1990 page 250.</ref> Paget claimed that he had a subordinate write a more moderate version of the order and that he wrote a part himself in which he recommended lenient treatment of non-communists in order to secure their cooperation.{{sfn|Paget|1952|pp=194–195}} The German Army always disapproved of so-called "wild shootings" where troops would engage in sessions of indiscriminately shooting people on their own initiative, and it was normal when issuing orders calling for violence against civilians to warn against "arbitrary actions".{{sfn|Förster|1998|p=271}} The evidence for this order was first presented by prosecutor [[Telford Taylor]] on 10 August 1946, in Nuremberg. Manstein acknowledged that he had signed this order of 20 November 1941, but claimed that he did not remember it. The American historians Ronald Smelser and Edward Davies wrote in 2008 that Manstein was a vicious anti-Semite of the first order who whole-heartedly agreed with Hitler’s idea that the war against the Soviet Union was a war to exterminate "Judeo-Bolshevism" and that was simply committing perjury when he claimed he could not remember his version of the "Severity Order".{{sfn|Smelser|Davies|2008|p=98}} Others describe him as opportunistic, like many German career officers, who initially resented the Nazis, but when this could have threatened his career, he adopted a positive stance towards the Nazi regime.{{sfn|Forczyk|2010|pp=61–62}} |

|||

The prosecution, led by senior counsel [[Arthur Comyns Carr]], took twenty days to present their evidence in court. Manstein was presented with an order he had signed on 20 November 1941 which he had drafted based on the [[Severity Order]] that had been issued by Field Marshal [[Walther von Reichenau]] on 10 October 1941. Manstein claimed in court that he remembered asking for a draft of such an order, but had no recollection of signing it. The order called for the elimination of the "Jewish Bolshevik system" and the "harsh punishment of Jewry".{{sfn|Melvin|2010|pp=243, 466, 475}} The prosecution used this order to build their case that Manstein had known about and was complicit with the genocide. Whether or not Manstein was responsible for the activities of ''Einsatzgruppe'' D, a unit not under his direct control but operating in his zone of command, became one of the key points of the trial—the prosecution claimed that is was Manstein's duty to know about the activities of this unit and also his duty to put a stop to their genocidal operations.{{sfn|Melvin|2010|p=475–477}} |

|||

Manstein's defence, led by the prominent lawyer [[Reginald Thomas Paget]], argued that Manstein was not compelled to disobey orders given by his sovereign government, even if such orders were illegal. Paget claimed that the only commissars Manstein had ordered shot were in the rear area in the Crimea, likely because of partisan activities. Manstein, speaking in his own defence, stated that he found the Nazi racial policy to be repugnant. Sixteen other witnesses were called for the defence, several of whom were members of his staff, who testified that Manstein had no knowledge of or involvement in the genocide.{{sfn|Melvin|2010|pp=466, 477–480}}{{sfn|Paget|1952|p=230}} |

|||

The "Severity Order" was a major piece of evidence for the prosecution at his Hamburg trial. At this trial, Paget argued that the order was justified because he claimed that many partisans were Jews, and so Manstein's order calling for every Jewish men, women and child to be executed was justified by his desire to protect his men from partisan attacks.{{sfn|Smelser|Davies|2008|p=101}} In the same way, Paget called the Russians "savages", and argued that Manstein showed much restraint as a "decent German soldier" in allegedly upholding the laws of war when fighting against the Russians who at all times displayed the most "appalling savagery".{{sfn|Smelser|Davies|2008|p=101}} |

|||

While Paget got Manstein acquitted of many of the seventeen charges, he was still found guilty of two charges and accountable for seven others, mainly for employing [[scorched earth]] tactics and for failing to protect the civilian population,<ref>[[Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives]]</ref> and was sentenced on 19 December 1949, to 18 years imprisonment which was near the maximum for the charges that were retained. This caused a massive uproar among Manstein's supporters and the sentence was subsequently reduced to 12 years. As part of his work championing his client, Paget published a best-selling book in 1951 about Manstein's career and his trial, which portrayed Manstein as an honourable soldier fighting heroically despite overwhelming odds on the Eastern Front, who had been convicted of crimes that he did not commit.{{sfn|Smelser|Davies|2008|pp=101–102}} Paget's book helped to contribute to the growing cult surrounding Manstein's name.{{sfn|Smelser|Davies|2008|p=102}} He was released on 6 May 1953 for what were officially described as medical reasons, but was in fact due to strong pressure from the West German government, who saw Manstein as a hero.{{sfn|Smelser|Davies|2008|p=98}} |

While Paget got Manstein acquitted of many of the seventeen charges, he was still found guilty of two charges and accountable for seven others, mainly for employing [[scorched earth]] tactics and for failing to protect the civilian population,<ref>[[Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives]]</ref> and was sentenced on 19 December 1949, to 18 years imprisonment which was near the maximum for the charges that were retained. This caused a massive uproar among Manstein's supporters and the sentence was subsequently reduced to 12 years. As part of his work championing his client, Paget published a best-selling book in 1951 about Manstein's career and his trial, which portrayed Manstein as an honourable soldier fighting heroically despite overwhelming odds on the Eastern Front, who had been convicted of crimes that he did not commit.{{sfn|Smelser|Davies|2008|pp=101–102}} Paget's book helped to contribute to the growing cult surrounding Manstein's name.{{sfn|Smelser|Davies|2008|p=102}} He was released on 6 May 1953 for what were officially described as medical reasons, but was in fact due to strong pressure from the West German government, who saw Manstein as a hero.{{sfn|Smelser|Davies|2008|p=98}} |

||

Manstein claimed ignorance of what was happening in the concentration camps. In the Nuremberg Trials, he was asked "Did you at that time know anything about conditions in the concentration camps?" to which he replied: "No. I heard as little about that as the German people, or possibly even less, because when one was fighting 1,000 kilometres away from Germany, one naturally did not hear about such things. I knew from pre-war days that there were two concentration camps, [[Oranienburg]] and [[Dachau]], and an officer who at the invitation of the SS had visited such a camp told me that it was simply a typical collection of criminals, besides some political prisoners who, according to what he had seen, were being treated severely but correctly."<ref>[http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/08-10-46.asp Nuremberg trials proceedings, Vol. 20, page 615, August 10, 1946]</ref> However, Manstein ignored the massacres committed in the occupied areas of the Soviet Union by the ''[[Einsatzgruppen]]'' who travelled in the wake of the German Army, including Manstein's own 11th Army.{{sfn|Smelser|Davies|2008|p=43}} That Manstein was well aware of the ''Einsatzgruppen'' massacres is proven by a 1941 letter he sent to [[Otto Ohlendorf]], where Manstein demands Ohlendorf hand over the wrist-watches of murdered Jews, which Manstein wrote was unfair since his men were doing so much to help Ohlendorf's men with their work.{{sfn|Smelser|Davies|2008|p=43}} Smelser and Davies note that Manstein's letter complaining that the SS were keeping all of the wrist-watches of murdered Jews to themselves was the only time that Manstein ever complained about the actions of the ''Einsatzgruppen'' in the entire Second World War.{{sfn|Smelser|Davies|2008|p=43}} |

|||

===Post-war life and memoirs=== |

===Post-war life and memoirs=== |

||

Revision as of 03:49, 26 September 2012

Erich von Manstein | |

|---|---|

Generalfeldmarschall Erich von Manstein | |

| Born | 24 November 1887 Berlin, German Empire |

| Died | 9 June 1973 (aged 85) Irschenhausen, West Germany |

| Allegiance |

|

| Years of service | 1906–1944 |

| Rank | Generalfeldmarschall |

| Commands | |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords |

| Relations |

|

| Other work | Served as senior defence advisor to the West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer |

Erich von Manstein (24 November 1887 – 9 June 1973) was one of the most prominent commanders of Germany's World War II armed forces (Wehrmacht). During the war, he attained the rank of field marshal (Generalfeldmarschall) and was held in high esteem by other officers as one of the best military strategists.

He was the initiator and one of the planners of the Ardennes offensive alternative in the invasion of France in 1940. He received acclaim from the German leadership for the victorious battles of Perekop Isthmus, Kerch, Sevastopol and Kharkov. He commanded the failed relief effort at Stalingrad and the successful Cherkassy pocket evacuation. He was dismissed from service by Adolf Hitler in March 1944, due to his frequent clashes with Hitler over military strategy. In his memoirs, Verlorene Siege (1955), translated into English as Lost Victories, he was critical of Hitler above all for denying the Army flexible defensive maneuverability and for "over-reliance" on his "will", and critical of the attempt by other military officers on Hitler's life.[1]

In 1949, he was tried in Hamburg for war crimes and was convicted of "neglecting to protect civilian lives" and using scorched earth tactics which denied vital food supplies to the local population. He was sentenced to 18 years in prison, later reduced to 12, but only served four years before being released from a British prison in 1953. He became a military advisor to the West German government. His memoirs largely contributed to the myth of a "clean Wehrmacht", and only later after his death did Manstein's involvement in atrocities on the Eastern Front during the war become more prominent.

Early life

He was born Fritz Erich Georg Eduard von Lewinski in Berlin, the tenth son of a Prussian aristocrat and artillery general, Eduard von Lewinski (1829–1906), and Helene von Sperling (1847–1910). His father's family was of partial Polish origin, with the Brochwicz coat of arms (Brochwicz III).[2] Hedwig von Sperling (1852–1925), Helene's younger sister, married Lieutenant General Georg von Manstein (1844–1913); the couple were not able to have children, so it was decided that the child would be adopted by his uncle and aunt. They had previously adopted Martha, the daughter of Helene and Hedwig's deceased brother.[3]

Erich von Manstein's biological and adoptive father were both Prussian generals, and his mother's brother and both his grandfathers had also been Prussian generals (one of them, Albrecht Gustav von Manstein, had led a corps in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71). He was a nephew of Paul von Hindenburg, the future Generalfeldmarschall and President of Germany, whose wife, Gertrud, was a sister of Hedwig and Helene. He attended the Imperial Lyzeum, a Catholic Gymnasium in Strasbourg (1894–99).

After six years in the cadet corps (1900–1906) in Plön and Groß-Lichterfelde, he joined the Third Foot Guards Regiment (Garde zu Fuß) in March 1906 as an ensign. He was promoted to lieutenant in January 1907, and in October 1913, entered the Prussian War Academy.[4]

Early military career

World War I

During World War I, Manstein served on both the German Western and Eastern Fronts. He was stationed in Belgium at the onset of the war, but was soon transferred to East Prussia. During a German retreat from Warsaw in November 1914, he was severely wounded. He returned to duty in 1915, was promoted to captain, and became a staff officer. He served in Poland, and then in Serbia, where he was awarded the Iron Cross First Class. In April 1916, he was transferred to the Western Front, where he remained until 1918 as division-level staff officer. In 1918, he volunteered for the staff position with the Frontier Defence Force in Breslau (Wroclaw) and served there until 1919.[5]

Inter-war era

Manstein married Jutta Sibylle von Loesch, the daughter of a Silesian landowner, in 1920. She died in 1966. They had three children: a daughter named Gisela, and two sons, Gero (b. 31 December 1922) and Rüdiger (born 1929[6]). Gero died on the battlefield in the northern sector of the Eastern Front on 29 October 1942 while serving as a lieutenant in the Wehrmacht.[7]

Manstein remained in the armed forces after World War I. In the 1920s, he participated in the formation of the Reichswehr, the German Army of the Weimar Republic (restricted to 100,000 men by the Versailles Treaty[8]). He was appointed company commander in 1920 and battalion commander in 1922. In 1927, he was promoted to major and began serving with the General Staff, visiting other countries to learn about their military facilities. In 1933, the Nazi Party seized power in Germany, thus ending the Weimar period. The new regime renounced the Versailles Treaty and proceeded with large scale rearmament and expansion of the military.[9]

On 1 July 1935, Manstein was made the Head of Operations Branch of the Army General Staff (Generalstab des Heeres), part of the Army High Command (Oberkommando des Heeres).[10] During his tenure, Manstein was one of the people responsible for the development of Germany's first war plan targeting France, Fall Rot (Case Red).[11] It was also during this time that Manstein came into contact with Heinz Guderian and Oswald Lutz, who advocated drastic changes in warfare emphasising the role of the Panzer. However, officers like Ludwig Beck, Chief of the Army General Staff, were against such drastic changes, and therefore Manstein proposed the development of Sturmgeschütze, self-propelled assault guns that would provide heavy direct-fire support to infantry, as an alternative to the Panzers.[12] In World War II, the resulting StuG series proved to be one of the most successful and cost-effective German weapons.[13]

He was promoted on 1 October 1936, becoming the Deputy Chief of Staff (Oberquartiermeister I) to General Ludwig Beck.[10] On 4 February 1938, with the fall of Werner von Fritsch, Manstein was transferred to the command of the 18th Infantry Division in Liegnitz, Silesia, with the rank of Generalleutnant.[14] In late July 1938, Manstein wrote to Beck telling him that he shared Beck's concerns about Germany going ahead with an attack on Czechoslovakia planned for 1 October. Both men felt that Germany was not yet ready for war. Manstein urged Beck not to resign, but to leave matters of the political strategy to the politicians, and to focus his attention solely on obtaining military success.[15] On 20 April 1939, Manstein delivered a speech at the celebration of Hitler's 50th birthday, in which he praised Hitler as a leader sent by God to save Germany. He warned the "hostile world" that if it kept erecting "ramparts around Germany to block the way of the German people towards their future", then he would be quite happy to see the world plunged into another world war.[16][17] The rise of officers such as Manstein was a part of a broad tendency for technocratic officers, usually ardent National Socialists, to come to the fore. Israeli historian Omer Bartov wrote:

The combined gratification of personal ambitions, technological obsessions and nationalist aspirations greatly enhanced their identification with Hitler's regime as individuals, professionals, representatives of a caste and leaders of a vast conscript army. Men such as Beck and Guderian, Manstein and Rommel, Doentiz and Kesserlring, Milch and Udet cannot be described as mere soldiers strictly devoted to their profession, rearmament and the autonomy of the military establishment while remaining indifferent to and detached from Nazi rule and ideology. The many points of contact between Hitler and his young generals were thus important elements in the integration of the Wehrmacht into the Third Reich, in stark contradiction of its image as a "haven" from Nazism.[18]

World War II

Poland

On 18 August 1939, in preparation for Fall Weiss, the German invasion of Poland, Manstein was appointed Chief of Staff to Gerd von Rundstedt’s Army Group South. Here he worked along with von Rundstedt’s Chief of Operations, Colonel Günther Blumentritt, in the development of the operational plan. Von Rundstedt accepted Manstein’s plan calling for the concentration of the majority of the army group’s armoured units into Walther von Reichenau's 10th Army, with the objective of a decisive breakthrough which would lead to the encirclement of Polish forces west of the Vistula River. In Manstein’s plan, two other armies comprising Army Group South, Wilhelm List’s 14th Army and Johannes Blaskowitz’s 8th Army, would provide flank support for Reichenau’s armoured thrust towards Warsaw, the Polish capital. Privately, Manstein was lukewarm about the Polish campaign, thinking that it would be better to keep Poland as a buffer between Germany and the Soviet Union. He also worried about an Allied attack on the West Wall once the Polish campaign was underway, thus drawing Germany into a two-front war.[19]

Manstein took part in conference on 22 August 1939 where Hitler underlined to his commanders the need for the physical destruction of Poland as a nation. After the war, he would state in his memoirs that he did not recognise at the time of this meeting that Hitler was going to pursue a policy of extermination against the Poles.[20] He did become aware of the policy later on, as he and other Wehrmacht generals received reports[21][22] on the activities of the Einsatzgruppen, the Schutzstaffel (SS) death squads tasked with following the army into Poland to kill intellectuals and other civilians.[23]These squads were also assigned to round up Jews and others for relocation to ghettos and Nazi concentration camps. Manstein later faced three charges of war crimes relating to Jewish and civilian deaths in the sectors under his control, and the mistreatment and deaths of prisoners of war.[24]

Launched on 1 September 1939, the invasion began successfully. In Army Group South's area of responsibility, under von Rundstedt, the 8th, 10th, and 14th Armies pursued the retreating Poles. The initial plan was for the 8th Army, the northernmost of the three, to advance towards Łódź. The 10th Army, with its motorized divisions, was to move quickly towards the Vistula, and the 14th Army was to advance and attempt to encircle the Polish troops in the Krakow area. These actions led to the encirclement and defeat of Polish forces in the Radom area on 8–14 September by six German corps. The flexibility and agility of the German forces led to the defeat of nine Polish infantry divisions and other units in the Battle of the Bzura (8–19 September), the largest engagement of the war thus far. Warsaw, under heavy air attack all month, was subjected to artillery bombardment in the second half of September, with substantial civilian loss of life.[25] The city surrendered on 27 September, and the last Polish military units surrendered on 6 October.[26]

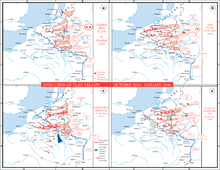

France

On 27 September 1939, the same day that Warsaw surrendered, Hitler ordered the Army High Command, led by General Franz Halder, to develop a plan for action in the west against France and the Low Countries. The various plans suggested by the General Staff were given to Manstein and his staff, who, with von Rundstedt's approval, formalized an alternative plan for Fall Gelb (Case Yellow). This plan received Hitler's attention in February 1940 and finally his agreement.[27]

By late October 1939, the bulk of the German Army had been redeployed to the west. Manstein was made Chief of Staff of von Rundstedt’s Army Group A in western Germany. Like many of the army's younger officers, Manstein opposed the initial plan for Fall Gelb, criticizing it for its lack of ability to deliver strategic results and the uninspired use of armoured forces. Manstein pointed out that a repeat of the Schlieffen Plan, with the attack directed through Belgium, was something the Allies expected, as they were already moving strong forces into the area. Bad weather in the area caused the attack to be cancelled several times and eventually delayed into the spring.[27]

During the autumn, Manstein, with the informal cooperation of Heinz Guderian, developed his own plan; he suggested that the Panzer divisions attack through the wooded hills of the Ardennes where no one would expect them, then establish bridgeheads on the Meuse River and rapidly drive to the English Channel. The Germans would thus cut off the French and Allied armies in Belgium and Flanders. Manstein's proposal also included a second thrust, outflanking the Maginot Line, which would have allowed the Germans to force any future defensive line much further south. The plan was after the event nicknamed Sichelschnitt (sickle cut).[27][28]

The Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) originally rejected the proposal. Halder had Manstein removed from von Rundstedt's headquarters and sent to the east to command the 38th Army Corps. But Hitler, looking for a more aggressive plan, approved a modified version of Manstein's ideas, today known as the Manstein Plan. Formulated by Halder, it did not contain the second thrust. Manstein and his corps played a minor role during the operations in France, serving under Günther von Kluge's 4th Army. However, it was his corps which helped to achieve the first breakthrough during Fall Rot, east of Amiens, and was the first to reach and cross the River Seine. The invasion of France was an outstanding military success, and Manstein was promoted to full general and awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross.[27][29]

Seelöwe

Manstein was a proponent of the prospective German invasion of Great Britain, named Operation Seelöwe. He considered the operation risky but necessary. Early studies by various staff officers determined that air superiority was a prerequisite to the planned invasion. His corps was to be shipped across the English Channel from Boulogne to Bexhill as one of four units assigned to the first wave; but as the Luftwaffe failed to decisively beat the Royal Air Force during the Battle of Britain, Operation Seelöwe was postponed indefinitely on 12 October. For the rest of the year, Manstein, with little to do, spent most of the time in Paris or at home.[30][31]

Barbarossa

In early 1941, the German High Command commenced planning the invasion of the Soviet Union, codenamed Operation Barbarossa. On 15 March, Manstein was appointed commander of the 56th Panzer Corps; he was one of 250 commanders to be briefed for the upcoming major offensive, first seeing detailed plans of the offensive in May. His corps was part of the Fourth Panzer Group under the command of General Erich Hoepner in Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb's Army Group North.[32] The Army Group was tasked with thrusting through the Baltic States and then advancing on Leningrad. Manstein arrived at the front only six days prior to the launch of the offensive. Operation Barbarossa commenced on 22 June 1941 with a massive German attack along the whole front line. Manstein's corps was tasked to advance with Georg-Hans Reinhardt's XLI Panzer Corps to the Dvina River to secure the bridges near the town of Daugavpils.[33] The Soviets mounted a number of counterattacks, but those were aimed against Reinhardt's corps, leading to the Battle of Raseiniai. Manstein's corps advanced rapidly, reaching the Dvina River, 315 kilometres (196 mi) distant, in just 100 hours. Overextended and well ahead of the rest of the army group, he was subjected to a number of determined Soviet counterattacks, which he was able to fend off.[34] After Reinhardt's corps closed in, the two corps were tasked with encircling the Soviet formations around Luga in a pincer movement. Again having penetrated deep into the Soviet lines with unprotected flanks, his corps was the target of a Soviet counteroffensive at Soltsy by the Soviet 11th Army, commanded by Nikolai Vatutin. During this attack from 15 July on, Manstein's 8th Panzer Division was cut off. Although it was able to fight its way free, it was badly mauled, and the Soviets succeeded in halting Manstein's advance at Luga, and he had his corps regroup at Dno.[35][36] The 8th Panzer were sent on anti-partisan duties and Manstein was given an SS police division. The attack on Luga was repeatedly delayed.[37]

The assault on Luga was still underway when Manstein received orders on 10 August that his next task would be to begin the advance toward Leningrad. No sooner had he moved to his new headquarters at Lake Samro than he was told to send his men towards Staraya Russa to relieve the X Corps, which was in danger of being encircled. On 12 August, the Soviets had launched an offensive with the 11th and 34th Armies against Army Group North, cutting off three divisions. Frustrated with the loss of the 8th Panzer and the opportunity to advance on Leningrad, Manstein returned to Dno. His counteroffensive led to a major Soviet defeat when he was able to encircle five Soviet divisions, receiving air support for the first time on that front. His unit captured 12,000 prisoners and 141 tanks. His opponent, General Kuzma M. Kachanov of the 34th Army, was subsequently court martialed and executed for the defeat. Manstein tried to obtain rest days for his men, who had been constantly fighting in poor terrain and increasingly poor weather since the start of the campaign, but to no avail. They were ordered to advance to the east on Demyansk. On 12 September, when he was near the city, he was informed that he would take over 11th Army of Army Group South in Ukraine.[36][38]

Crimea and the Battle of Sevastopol

In September 1941, Manstein was appointed commander of the 11th Army after its previous commander, Colonel-General Eugen Ritter von Schobert, perished when his plane landed in a Russian minefield. The 11th Army was tasked with invading the Crimea, capturing Sevastopol, and pursuing enemy forces on the flank of Army Group South during its advance into Russia.[39][40] Hitler's intention was to prevent the Russians from using airbases there, and to cut off the Russian supply of oil from the Caucasus.[41]

Manstein's forces—mostly infantry—achieved a rapid breakthrough during the first days against heavy Soviet resistance. After most of the neck of the Perekop Isthmus had been taken, his forces were substantially reduced, leaving six German divisions and the Romanian Third Army. The rest of the Perekop Isthmus was captured slowly and with some difficulty; Manstein complained of a lack of air support to contest Russian air superiority in the region. He next created a mobile reconnaissance unit to press down the peninsula, cutting the road between Simferopol and Sevastopol on 31 October. Simferopol was captured the next day. The 11th Army had captured all of the Crimean Peninsula—except for Sevastopol—by 16 November. Meanwhile, the Red Army had evacuated 300,000 personnel out of the city by sea.[42][43]

Manstein's first attack on Sevastopol in November failed, and with insufficient forces left for an immediate assault, he ordered an investment of the heavily fortified city. By 17 December, he launched another offensive, which also failed. On 26 December, the Soviets landed on the Kerch Straits to retake Kerch and its peninsula, and on 30 December executed another landing near Feodosiya. Only a hurried withdrawal from the area, in contravention of Manstein's orders, by the 46th Infantry Division under General Hans Graf von Sponeck prevented a collapse of the eastern part of the Crimea; the division lost most of its heavy equipment. Manstein cancelled a planned resumption of the attack and sent most of his forces east to destroy the Soviet bridgehead. The Soviets were in a superior position regarding men and materiel as they were able to re-supply by sea, and were therefore pushed by Stalin to conduct further offensives. However, the Russians were unable to capture the critical rail and road access points which would have cut the German lines of supply.[44][45]

For the Battle of the Kerch Peninsula, launched on 8 May 1942, Hitler finally assigned Manstein major air support. The 11th Army was outnumbered on the ground, so he had them feint an attack in the north while the bulk of the force attacked to the south. The Soviets were soon fleeing. Manstein recorded in his memoirs the capture of "170,000 prisoners, 1,133 guns, and 258 tanks".[46] Kerch was captured on 16 May. The Germans lost only 8,000 men.[47][48]

After a month's delay, Manstein turned his attention once more to the capture of Sevastopol, a battle in which Germany used some of the largest guns ever built. Along with large numbers of regular artillery pieces, super-heavy 600mm mortars and the 800mm "Dora" railway gun were brought in for the assault. A furious barrage began on the morning of 2 June 1942, and all of the resources of the Luftwaffe's Luftflotte 4, commanded by Wolfram von Richthofen, were committed, continuing for five days before the ground assault began.[49][50]

The 11th Army gained ground during mid-June, focusing their attention on the northern approaches to the city. Casualties were high on both sides as the month dragged on. Aware of the need to act before the German summer offensive of 1942 reduced the availability of reinforcements and supplies, Manstein ordered a surprise attack using amphibious landings across Severnaya Bay on 29 June. The operation was a success; Soviet resistance crumbled. On 1 July, German forces entered the city while the Soviets conducted a disorganised evacuation: by 4 July, the entire city was in German hands. Hitler promoted Manstein to Generalfeldmarschall in August.[50][51][52]

During the Crimean campaign, Manstein was indirectly involved in atrocities against the Soviet population, especially those committed by Einsatzgruppe D, one of several Schutzstaffel (SS) groups that had been tasked with the elimination of the Jews of Europe. Einsatzgruppe D travelled in the wake of Manstein's 11th Army, and were provided by Manstein's command with vehicles, fuel, and drivers. Military police cordoned off areas where the Einsatzgruppe planned to shoot Jews to prevent anyone from escaping. Captain Ulrich Gunzert, shocked to have witnessed Einsatzgruppe D massacre a group of Jewish women and children, went to Manstein to ask him to do something to stop the killings. Gunzert states that Manstein told him to forget what he had seen and to focus on fighting the Red Army. Gunzert later called Manstein's inaction "a flight from responsibility, a moral failure".[53] Eleven of the seventeen charges against Manstein at his later war crimes trial were related to Nazi maltreatment and killing of Jews and prisoners of war in the Crimea.[54]

Leningrad

After the capture of Sevastopol, the Hitler felt Manstein was the right man to command the forces at Leningrad, which had been under siege since September 1941. With elements of the 11th Army, Manstein was transferred to the Leningrad front, arriving on 27 August 1942. Manstein again lacked the proper forces to storm the city, so he planned Operation Nordlicht, a bold plan for a thrust to cut off Leningrad's supply line at Lake Ladoga.[55]

However, on the day of his arrival, the Soviet launched the Sinyavin Offensive. Originally planned as spoiling attack against Georg Lindemann's 18th Army in the narrow German salient west of Lake Ladoga, the offensive appeared able to break through the German lines, lifting the siege. Hitler, bypassing the usual chain of command, telephoned Manstein directly and ordered him to take offensive action in the area. After a series of heavy battles, he launched a counterattack on 21 September that cut off the two Soviet armies in the salient. Fighting continued throughout October. Although the Soviet offensive was fended off, the resulting attrition meant that the Germans could no longer execute a decisive assault on Leningrad, and Nordlicht was put on hold.[56][57] The siege was finally lifted by the Soviets in January 1944.[58]

Stalingrad

In an attempt to resolve their persistent shortage of oil, the Germans had launched Case Blue, a massive offensive aimed against the Caucasian oilfields, in the summer of 1942.[59] After German air attacks, the 6th Army, led by Friedrich Paulus, was tasked with capturing Stalingrad, a key city on the Volga River. His troops, supported by 4th Panzer Army, entered the city on 12 September. Hand-to-hand combat and street fighting ensued.[60] The Soviets launched a huge counteroffensive on 19 November, codenamed Operation Uranus, which was designed to encircle the German armies and trap them in the city; this goal was accomplished on 23 November.[61] Manstein's initial assessment on 24 November was that the 6th Army, given adequate air support, would be able to hold on. Hitler, aware that if Stalingrad were lost it would likely never be retaken, appointed Manstein as commander of the newly created Army Group Don (Heeresgruppe Don), tasked with mounting a relief operation named Operation Winter Storm (Unternehmen Wintergewitter), to reinforce the German hold on the city.[62][63]

Launched on 12 December, Winter Storm achieved some initial success. Manstein's three Panzer divisions (comprising the 23rd Panzer Grenadier Division and the 6th and 17th Panzer Divisions) and supporting units of the 57th Panzer Corps within 48 km (30 mi) of Stalingrad by 20 December at the Myshkova River, where they came under assault by Soviet tanks in blizzard conditions. Manstein made a request to Hitler on 18 December that 6th Army should attempt to break out.[64] Hitler was against it, and both Manstein and Paulus were reluctant to openly disobey his orders.[65] Conditions deteriorated inside the city; the men suffered from lice, the cold weather, and inadequate supplies of food and ammunition. Reichsminister of Aviation Hermann Göring had assured Hitler that the trapped 6th Army could be adequately supplied by air, but due to poor weather, a lack of aircraft, and mechanical difficulties, this turned out not to be the case.[66] On 24 January Manstein urged Hitler to allow Paulus to surrender, but he refused.[67] In spite of Hitler's wishes, Paulus surrendered with his remaining 91,000 troops on 31 January 1943. Some 200,000 German and Romanian soldiers died; of those who surrendered, only 6,000 survivors returned to Germany at the end of the war.[68]

American historians Williamson Murray and Allan Millett wrote that Manstein's message to Hitler on November 24 advising him that the 6th Army should not break out, along with Göring's statements that the Luffwaffe could supply Stalingrad, "... sealed the fate of Sixth Army".[69] Historians, including Gerhard Weinberg, have pointed out that Manstein's version of the events at Stalingrad in his memoir is distorted and several events described there were probably made up.[70][71] "Because of the sensitivity of the Stalingrad question in post-war Germany, Manstein worked as hard to distort the record on this matter as on his massive involvement in the murder of Jews", wrote Weinberg.[72]

Meanwhile, the Soviets launched an offensive of their own. Operation Saturn was intended to capture Rostov and thus cut off the German Army Group A. However, after the launch of Winter Storm, the Soviets had to reallocate forces to prevent the relief of Stalingrad, so the operation was scaled down and redubbed "Little Saturn". The offensive forced Manstein to divert forces to avoid the collapse of the entire front. The attack also prevented the 48th Panzer Corps (comprising the 336th Infantry Division, the 3rd Luftwaffe Field Division, and the 11th Panzer Division), under the command of General Otto von Knobelsdorff, from joining up with the 57th Panzer Corps as planned to aid the relief effort. Instead, the 48th Panzer Corps held a line along the Chir River, beating off successive Russian attacks. General Hermann Balck used the 11th Panzer Division to counterattack Soviet salients. On the verge of collapse, the German units were able to hold the line, but the Italian 8th Army on the flanks was overwhelmed and subsequently destroyed.[73][74]

Spurred on by this success, the Soviets planned a series of follow-up offensives in January and February 1943 intended to decisively beat the Germans in southern Russia. After the destruction of the remaining Hungarian and Italian forces during the Ostrogozhsk–Rossosh Offensive, Operation Star and Operation Gallop were launched to recapture Kharkov and Kursk and to cut off all German forces east of Donetsk. Those operations succeeded in breaking through the German lines and threatened the whole southern part of the German front. To deal with this threat, Army Group Don, Army Group B, and parts of Army Group A were united as Army Group South (Heeresgruppe Süd) under Manstein's command in early February.[74][75]

Kharkov operation

During their offensives in February 1943, the Soviets broke through the German lines, retaking Kursk on 9 February.[76] As Army Groups B and Don were in danger of being surrounded, Manstein repeatedly called for reinforcements. Although Hitler called on 13 February for Kharkov to be held "at all costs",[76] Commander Paul Hausser ordered the city evacuated on 15 February.[77] Hitler arrived at the front in person on 17 February, and over the course of three days of exhausting meetings, Manstein convinced him that offensive action was needed in the area to regain the initiative and prevent encirclement. Troops were reorganised and reinforcements were pulled into the zone from neighbouring armies. Manstein immediately began planning a counter-offensive, which was launched on 20 February. By 2 March, the Germans had captured 615 tanks and had killed some 23,000 Russian soldiers.[78]

To reinforce the point that the recapture of Kharkov was important politically, Hitler returned to the front on 10 March. Manstein carefully assembled his available forces along a wide front to prevent their encirclement, and recaptured Kharkov on 14 March, after bloody street fighting in the Third Battle of Kharkov.[79] For this accomplishment, he received the Oak Leaves for the Knight's Cross.[80] Hausser's II SS Panzer Corps then captured Belgorod on 18 March. The spring thaw began a few days later, ending operations in the area for the time being. Planning was then undertaken to eliminate the enemy salient at Kursk.[81]

Operation Zitadelle

Manstein favoured an immediate pincer attack on the Kursk salient after the battle at Kharkov, but Hitler was concerned that such a plan would draw forces away from the industrial region in the Donets Basin. In any event, the ground was still too muddy to move the tanks into position. In lieu of an immediate attack, the OKH prepared Operation Zitadelle (Citadel), the launching of which would be delayed while more troops were gathered in the area and the mud solidified. Meanwhile the Soviets, well aware of the danger of encirclement, also moved in large numbers of reinforcements, and their intelligence reports had revealed the expected locations and timing of the German thrusts.[82][83]

Citadel was the last German strategic offensive on the Eastern Front, and one of the largest battles in history, involving more than four million men. By the time the Germans launched their initial assault on 5 July 1943, the Russians outnumbered them by nearly three to one. Walther Model was in command of the northern pincer, with the Ninth Panzer Army, while Manstein's Army Group South formed the southern pincer. Both armies were slowed as the tanks were blown up in minefields, and after five days of fighting Model's advance was stopped. Manstein's forces were able to penetrate the Soviet lines, causing heavy casualties, and he reached Prokhorovka, his first major objective, on 11 July. In spite of disastrous Soviet losses in the resulting Battle of Prokhorovka, Hitler called off the Kursk offensive; the Allies had landed in Sicily, so he issued the order for a withdrawal.[84] Manstein protested, asserting that the victory was almost at hand. He felt that the Soviets had exhausted all their reserves in the area. But Hitler was adamant.[85] Although Soviet casualties were indeed heavy, modern historians usually discount the possibility of a successful German continuation of the offensive.[86][87][88]

From Kursk to the Dnieper

Manstein regarded the Battle of Kursk as something of a German victory, as he believed that he had destroyed much of the Red Army's offensive capacity for the rest of 1943. This assessment turned out to be incorrect, as the Soviets were able to recover much more quickly than anyone expected. Manstein moved his panzer reserves to the Mius River and the lower Dnieper, not realising the Soviet activities there were a diversion. A Soviet offensive that began on 3 August put Army Group South under heavy pressure. After two days of heavy fighting, the Soviets broke though the German lines and retook Belgorod, punching a 56 km (35 mi) wide hole between Fourth Panzer Army and Armee Abteilung Kempf, tasked with holding Kharkov. In response to Manstein's demands for reinforcements, Hitler sent the Großdeutschland, 7th Panzers, SS 2nd Das Reich, and SS 3rd Totenkopf.[89][90][91]

Construction began of defensive positions along the Dnieper, but Hitler refused requests to pull back, insisting that Kharkov be held. With reinforcements trickling in, Manstein waged a series of counter-attacks and armoured battles near Bohodukhiv and Okhtyrka between 13 and 17 August, which resulted in heavy casualties as they ran into prepared Soviet lines. On 20 August he informed the OKH that his forces in the Donets river area were holding a too-wide front with insufficient numbers, and that he needed to either withdraw to the Dnieper River or receive reinforcements. Continuous pressure from the Soviets had separated Army Group Centre from Army Group South and severely threatened Manstein's northern flank. When the Soviets threw their main reserves behind a drive to retake Kharkov on 21–22 August, Manstein took advantage of this to close the gap between the 4th and 8th Panzer Armies and reestablish a defensive line. Hitler finally allowed Manstein to withdraw back across the Dnieper on 15 September.[90][92][93] During the withdrawal, Manstein ordered scorched earth actions to be taken in a zone 20 to 30 kilometres (12 to 19 mi) from the river, and later faced charges at his war crimes trial for issuing this order.[94] Soviet losses in July and August included over 1.6 million casualties, 10,000 tanks and self-propelled artillery pieces, and 4,200 aircraft. German losses, while only one-tenth that of the Russian losses, were much more difficult to sustain, as there were no further reserves of men and materiel to draw on.[95] In a series of four meetings that September, Manstein tried unsuccessfully to convince Hitler to reorganise the high command and let his generals make more of the military decisions. [96]

Dnieper campaign

In September 1943 Manstein withdrew to the west bank of the Dnieper in an operation that for the most part was well-ordered, but at times degenerated into a disorganized rout as his exhausted soldiers became "unglued".[97] Hundreds of thousands of Russian civilians traveled west with them, many bringing livestock and personal property.[98] Manstein correctly deduced that the next Soviet attack would be towards Kiev, but as had been the case throughout the campaign, the Soviets used maskirovka (deception) to disguise the timing and exact location of their intended offensive.[99] Murray and Millett wrote that many German generals' "fanatical belief" in Nazi racial theories " ... made the idea that Slavs could manipulate German intelligence with such consistency utterly inconceivable".[100] The brigade-strength 1st Ukrainian Front, led by Nikolai Fyodorovich Vatutin, met the outnumbered Fourth Panzer Army near Kiev. Vatutin first made a thrust near Liutezh, just north of Kiev, and then attacked near Bukrin, to the south, on 1 November. The Germans, thinking Bukrin would be the location of the main attack, were taken completely by surprise when Vatutin captured the bridgehead at Liutezh and gained a foothold on the west bank of the Dnepr. Kiev was liberated on 6 November.[101] The Seventeenth Army was cut off and isolated in the Crimea by the attacking 4th Ukrainian Front on 28 October.[102]

Under the guidance of General Hermann Balck, the cities of Zhytomyr and Korosten were retaken in mid-November,[101] but most of the German forces were concentrated against the smaller decoy forces, and the Soviets continued to succeed. Manstein's repeated requests to Hitler for more reinforcements were turned down.[103] On 4 January 1944 Manstein met with Hitler to tell him that the Dnieper line was untenable and that he needed to retreat in order to save his forces.[104] Hitler refused, and Manstein again requested changes in the highest levels of the military leadership, but was turned down, as Hitler believed that he alone was capable of managing the wider strategy.[105]

In January Manstein was forced to retreat further west by the Soviet offensive. Without waiting for permission from Hitler, he ordered the German XI and XXXXII Corps (consisting of 56,000 men in six divisions) of Army Group South to break out of the Korsun Pocket during the night of 16–17 February 1944. By the beginning of March, the Soviets had driven the Germans well back of the river. Because of Hitler's directive of 19 March that from that point forward all positions were to be defended to the last man, Manstein's First Panzer Army became encircled on 21 March when permission to break out was not received from Hitler in time. Manstein flew to Hitler's headquarters in Lvov to try to convince him to change his mind. Hitler eventually relented, but relieved Manstein of his command on 30 March 1944.[106]

Manstein appeared on the cover of the 10 January 1944 issue of Time magazine, above the caption "Retreat may be subtle, but victory lies in the other direction".[107][108]

Dismissal

Manstein received the the Swords of the Knight's Cross—the third highest German military honour—on 30 March 1944,[109] and handed over control of Army Group South to Walther Model on 2 April. While on medical leave after surgery to remove a cataract in his right eye, Manstein recovered at home in Liegnitz and in a medical facility in Dresden. He suffered from an infection and for a time was in danger of losing his sight. On the day of the failed 20 July plot, an assassination attempt on Hitler's life that was part of a planned military coup d'état, Manstein was at a seaside resort on the Baltic. Although he had met at various times with three of the main conspirators— Claus von Stauffenberg, Henning von Tresckow, and Rudolf Christoph Freiherr von Gersdorff—Manstein was not involved in the conspiracy; he later said "Preussische Feldmarschälle meutern nicht" – "Prussian field marshals do not mutiny."[110] Still, the Gestapo placed Manstein's house under surveillance.[111]

When it became obvious that Hitler would not be appointing him to a new post, Manstein bought an estate in East Pomerania in October 1944, but was soon forced to abandon it as Soviet forces overran the area. His home at Liegnitz had to be evacuated on 22 January 1945, and he and his family took refuge temporarily with friends in Berlin. While there, Manstein tried to get an audience with Hitler in the Führerbunker, but was turned away. He and his family continued to move further west into Germany until the war in Europe ended with a German defeat in May 1945. Manstein suffered further complications in his right eye and was receiving treatment in a hospital in Heiligenhafen when he was arrested by the British and transferred to a prisoner of war camp near Lüneburg on 26 August.[112][113][114]

Postwar

Trial

Manstein was moved to Nuremberg in October 1945. He was held at the Palace of Justice, the location of the Nuremberg Trials of major Nazi war criminals and organisations. While there, Manstein helped prepare a 132-page document for the defense of the General Staff and the OKW, on trial at Nuremberg in August 1946. The myth that the Wehrmacht was "clean"—not culpable for the events of the Holocaust—arose partly as a result of this document, written largely by Manstein, along with General of Cavalry Sigfried Westphal. He also gave oral testimony about the Einsatzgruppen, the treatment of prisoners of war, and the concept of military obedience, especially as related to the Commissar Order, an order issued by Hitler in 1941 requiring all Soviet political commissars to be shot without trial. Manstein admitted that he received the order, but said he did not carry it out. He denied any knowledge of the activities of the Einsatzgruppen, and testified that soldiers under his command were not involved in the murder of Jewish civilians. In September 1946 the General Staff and the OKW were declared to not be criminal organisations.[115]

After his testimony at Nuremberg, Manstein was interned by the British as a prisoner of war at Island Farm (also known as Special Camp 11) in Bridgend, Wales, where he awaited the decision as to whether or not he would face a war crimes trial. He mostly kept apart from the other inmates, taking solitary walks, tending a small garden, and beginning work on the drafts of two books. British author B. H. Liddell Hart was in correspondence with Manstein and others at Island Farm and visited inmates of several camps around Britain while preparing his best-selling 1947 book On the Other Side of the Hill. Liddell Hart was an admirer of the German generals; he described Manstein as an operational genius. The two remained in contact, and Liddell Hart later helped Manstein arrange the publication of the Engish edition of his memoir, Verlorene Siege (Lost Victories), in 1958.[116][117] The British cabinet, under pressure from the Soviet Union, finally decided in July 1948 to prosecute Manstein for war crimes. He and three other senior officers (Walther von Brauchitsch, Gerd von Rundstedt, and Adolf Strauss) were transferred to Munsterlager to await trial. Brauchitsch died that October, and Rundstend and Strauss were released on medical grounds in March 1949. Manstein's trial was held in Hamburg from 23 August to 19 December 1949.[118]

Manstein faced seventeen charges at the trial, three of which pertained to events in Poland and fourteen regarding events in the Soviet Union. The first and second charges regarding Poland accused him of authorising the killing, deportation, and maltreatment of Jews and other Polish civilians, and failing to prevent such killings and maltreatment. The third charge covered maltreatment and killing of Polish prisoners of war. The charges regarding events in the Soviet Union included the fourth charge, failing to attend to the needs of Soviet prisoners of war; many died through maltreatment or were executed by the Sicherheitsdienst (SD). The fifth charge regarded an order issued by Manstein on 20 September 1941 whereby captured Soviet soldiers were summarily killed without trial. The sixth charge claimed that captured Soviet soldiers were illegally recruited into German armed forces units. The seventh charge claimed that Soviet prisoners of war were illegally compelled to do dangerous work, and work of a military nature, which is prohibited by the Hague Convention. The eighth charge included fifteen cases of Soviet political commissars being executed in compliance with Hitler's Commissar Order.[119]

The remaining charges were related to the activities of Einsatzgruppe D in the Crimea. The ninth charge accused Manstein of authorising the execution of Jews and other Soviet citizens. The tenth charge accused him of failing to protect the lives of the civilians in the area. The eleventh charge claimed that soldiers in units commanded by Manstein handed over civilians to the Einstatsgruppe, while knowing that to do so would mean their deaths. The twelfth charge accused Manstein of authorising his troops to kill Jewish civilians in the Crimea. The thirteenth charge accused Manstein of authorising the killing of civilians for offences which they did not commit. The fourteenth charge accused Manstein of issuing orders to execute civilians without trial; for merely being suspects; and for having committed offences that did not warrant the death penalty. The fifteenth charge was that Soviet citizens, in violation of the Hague Convention, had been compelled to build defensive positions and dig trenches in combat areas. The sixteenth charge accused him of ordering the deportation of civilians as slave labourers. The final charge accused Manstein of issuing "scorched earth" orders while in retreat, while ordering the deportation of the civilians in the affected areas. The fourteenth and fifteenth charges were withdrawn before the trial for lack of supporting evidence.[120]

The prosecution, led by senior counsel Arthur Comyns Carr, took twenty days to present their evidence in court. Manstein was presented with an order he had signed on 20 November 1941 which he had drafted based on the Severity Order that had been issued by Field Marshal Walther von Reichenau on 10 October 1941. Manstein claimed in court that he remembered asking for a draft of such an order, but had no recollection of signing it. The order called for the elimination of the "Jewish Bolshevik system" and the "harsh punishment of Jewry".[121] The prosecution used this order to build their case that Manstein had known about and was complicit with the genocide. Whether or not Manstein was responsible for the activities of Einsatzgruppe D, a unit not under his direct control but operating in his zone of command, became one of the key points of the trial—the prosecution claimed that is was Manstein's duty to know about the activities of this unit and also his duty to put a stop to their genocidal operations.[122]

Manstein's defence, led by the prominent lawyer Reginald Thomas Paget, argued that Manstein was not compelled to disobey orders given by his sovereign government, even if such orders were illegal. Paget claimed that the only commissars Manstein had ordered shot were in the rear area in the Crimea, likely because of partisan activities. Manstein, speaking in his own defence, stated that he found the Nazi racial policy to be repugnant. Sixteen other witnesses were called for the defence, several of whom were members of his staff, who testified that Manstein had no knowledge of or involvement in the genocide.[123][124]

While Paget got Manstein acquitted of many of the seventeen charges, he was still found guilty of two charges and accountable for seven others, mainly for employing scorched earth tactics and for failing to protect the civilian population,[125] and was sentenced on 19 December 1949, to 18 years imprisonment which was near the maximum for the charges that were retained. This caused a massive uproar among Manstein's supporters and the sentence was subsequently reduced to 12 years. As part of his work championing his client, Paget published a best-selling book in 1951 about Manstein's career and his trial, which portrayed Manstein as an honourable soldier fighting heroically despite overwhelming odds on the Eastern Front, who had been convicted of crimes that he did not commit.[126] Paget's book helped to contribute to the growing cult surrounding Manstein's name.[116] He was released on 6 May 1953 for what were officially described as medical reasons, but was in fact due to strong pressure from the West German government, who saw Manstein as a hero.[53]

Post-war life and memoirs

Called on by West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, Manstein served as his senior defense advisor and chaired a military sub-committee appointed to advise the parliament on military organization and doctrine for the new German Army, the Bundeswehr, and its incorporation into NATO. He later moved with his family to Bavaria.

His war memoirs, Verlorene Siege (Lost Victories), were published in Germany in 1955, and translated into English in 1958. In them, he presented the thesis that if only he had been in charge of strategy instead of Hitler, the war on the Eastern Front could have been won.[127] Verlorene Siege was much acclaimed and a best-seller when it was published in the 1950s.[128] The favorable portrait Manstein drew of himself in Verlorene Siege continues to influence the popular picture of him to this day.[128] Because of his influence, for the first few years of the Bundeswehr he was seen as the unofficial chief of staff. Even later, his birthday parties were regularly attended by official delegations of Bundeswehr and NATO top leaders such as General Hans Speidel, who was the Commander-in-Chief of the Allied ground forces in Central Europe from 1957 to 1963. This was not the case with other field marshals such as Milch, Schörner, von Küchler and others, who were disregarded and forgotten after the war. By the mid-1950s, Manstein had become the object of a vast cult centered around him, which portrayed him as not only as one of Germany's greatest generals, but also one of the world's greatest generals ever. Manstein was described as a militärische Kult- und Leitfigur (military cult legend), a general of legendary, almost mythical ability and superhuman skill, much honored by both the public and historians.[129]

Erich von Manstein suffered a stroke and died in Munich on the night of 9 June 1973. He was buried with full military honours.[130] His obituary in The Times on 13 June 1973 states "His influence and effect came from powers of mind and depth of knowledge rather than by generating an electrifying current among the troops or 'putting over' his personality."[131]

Notes

- ^ Manstein 2004, pp. 273–288.

- ^ Kosk 2001.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 10.

- ^ Forczyk 2010, p. 6.

- ^ Forczyk 2010, p. 7.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 42.

- ^ Forczyk 2010, pp. 7–8, 28.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 36.

- ^ Forczyk 2010, pp. 7–9.

- ^ a b Melvin 2010, p. 73.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 76.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 79–82.

- ^ Forczyk 2010, p. 9.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 100.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 97.

- ^ Kopp 2003.

- ^ Bartov 1999, p. 145.

- ^ Forczyk 2010, p. 11.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 117.

- ^ Longerich, Chapter 10 2003.

- ^ Lemay & Heyward 2010, pp. 81–88.

- ^ Evans 2008, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 469–470.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 120–125.

- ^ Evans 2008, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d Forczyk 2010, pp. 11–14.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 145.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 178–179.

- ^ Forczyk 2010, p. 16.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 186, 193.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 205.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 217–218.

- ^ a b Forczyk 2010, pp. 16–20.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 220–221.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 221–224.

- ^ Forczyk 2010, p. 20.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 227.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 229.

- ^ Forczyk 2010, p. 21.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 233–235, 237.

- ^ Forczyk 2010, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 238–239, 247, 252.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 259.

- ^ Forczyk 2010, p. 23.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 256–259.

- ^ Forczyk 2010, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b Glantz 1995, pp. 94, 117.

- ^ Forczyk 2010, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 265–270.

- ^ a b Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 98.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 240.

- ^ Forczyk 2010, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Forczyk 2010, pp. 25–28.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 275–278.

- ^ Evans 2008, p. 621.

- ^ Glantz 1995, pp. 108–110.

- ^ Evans 2008, p. 410–411.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 282, 285.

- ^ Evans 2008, p. 413.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 287, 294.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 304–305.

- ^ Murray & Millett 2000, p. 289.

- ^ Evans 2008, pp. 413, 416–417.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 313.

- ^ Evans 2008, pp. 419–420.

- ^ Murray & Millett 2000, p. 288.

- ^ Weinberg 2005, p. 451.

- ^ Forczyk 2010, pp. 29, 62.

- ^ Weinberg 2005, p. 1045.

- ^ Nipe 2000, pp. 18–33.

- ^ a b Glantz 1995, pp. 143–147.

- ^ Nipe 2000, pp. 54–64, 110.

- ^ a b Melvin 2010, p. 333.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 334.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 338–341.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 343.

- ^ Manstein 2004, p. 565.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 343–344.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 350–351.

- ^ Evans 2008, p. 485.

- ^ Evans 2008, pp. 486–489.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 377–378.

- ^ Forczyk 2010, pp. 41–45.

- ^ Murray & Millett 2000, p. 298.

- ^ Glantz 1995, pp. 160–167.

- ^ Murray & Millett 2000, pp. 390–391.

- ^ a b Forczyk 2010, pp. 41–47.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 384–385.

- ^ Murray & Millett 2000, pp. 391–392.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 386–394.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 396, 471.

- ^ Evans 2008, pp. 489–490.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 387–392.

- ^ Murray & Millett 2000, p. 393.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 397.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 399.

- ^ Murray & Millett 2000, p. 395.

- ^ a b Melvin 2010, p. 402.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 400, Map 15.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 402, 404, 411.

- ^ Murray & Millett 2000, p. 396.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 410.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 414–418.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 412.

- ^ Time 1944.

- ^ Fellgiebel 2003, p. 38.

- ^ Beevor 1999, p. 276.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 420–425.

- ^ Forczyk 2010, p. 58–60.

- ^ Murray & Millett 2000, p. 401.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 425–431.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 432–448.

- ^ a b Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 102.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 452–456.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 460–463, 467.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 469–471.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 471–473.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 243, 466, 475.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 475–477.

- ^ Melvin 2010, pp. 466, 477–480.

- ^ Paget 1952, p. 230.

- ^ Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 95.

- ^ a b Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 90.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, pp. 90–92.

- ^ Melvin 2010, p. 503.

- ^ "Obituary: Field Marshal von Manstein: An outstanding German soldier". The Times. 13 June 1973. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

References

- Barnett, Correlli, ed. (2003) [1989]. Hitler's Generals. Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3994-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bartov, Omer (1999). "Soldiers, Nazis and War in the Third Reich". In Leitz, Christian (ed.). The Third Reich. London: Blackwell. pp. 129–150. ISBN 978-0-631-20700-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Beevor, Antony (1999). Stalingrad: The Fateful Siege, 1942–1943. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-028458-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Carver, Michael (1976). The War Lords: Military Commanders of the Twentieth Century. Boston: Little Brown & Co. ISBN 0-316-13060-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Citino, Robert M. (2012). The Wehrmacht Retreats: Fighting a Lost War, 1943. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1826-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Engelmann, Joachim (1981). Manstein, Stratege und Truppenführer: ein Lebensbericht in Bilder (in German). Friedberg: Podzun-Pallas-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7909-0159-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Evans, Richard J. (2008). The Third Reich At War. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-14-311671-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fellgiebel, Walther-Peer (2003) [2000]. Elite of the Third Reich: The Recipients of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939–1945: A Reference. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-874622-46-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Forczyk, Robert (2010). Manstein: Leadership – Strategy – Conflict. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-465-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fest, Joachim (1997). Plotting Hitler's Death: The German Resistance to Hitler, 1933–1945. New York: H. Holt. ISBN 0-8050-5648-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Förster, Jürgen (1998). "Complicity or Entanglement? The Wehrmact, the War and the Holocaust". In Berenbaum, Michael; Peck, Abraham (eds.). The Holocaust and History The Known, the Unknown, the Disputed and the Reexamined. Bloomington: Indian University Press. pp. 266–283. ISBN 978-0-253-33374-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Glantz, David M. (1995). When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0899-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Glantz, David M (2002). Black Sea Inferno: The German Storm of Sevastopol 1941–1942. Staplehurst: Spellmount. ISBN 1-86227-161-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kehrig, Manfred (1974). Stalingrad : Analyse und Dokumentation einer Schlacht (in German). Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt. ISBN 3-421-01653-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kopp, Roland (2003). "Die Wehrmacht feiert. Kommandeurs-Reden zu Hitlers 50. Geburtstag am 20. April 1939". Militärgeschichtliche Zeitschrift (in German). 62 (2). Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt: 471–535.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kosk, Henryk P (2001). Generalicja Polska: Popularny Słownik Biograficzny. T. 2, M - Ż, suplement. Pruszków: Oficyna Wydawnicza Ajaks. ISBN 978-83-87103-81-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lemay, Benoît; Heyward, Pierce (2010). Erich von Manstein: Hitler's Master Strategist. Havertown, PA; Newbury, Berkshire: Casemate. ISBN 978-1-935149-26-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Liddell Hart, B. H. (1999) [1948]. The Other Side of the Hill. London: Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-37324-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Longerich, Heinz Peter (2003), "10. Hilter and the Mass Murders in Poland 1939/40", Hitler's Role in the Persecution of the Jews by the Nazi Regime, Atlanta: Emory University, retrieved 19 July 2012.

- Manstein, Erich (1983). Verlorene Siege (in German). München: Bernard & Graefe. ISBN 3-7637-5253-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Manstein, Erich (2002). Soldat im 20. Jahrhundert (in German). München: Bernard & Graefe. ISBN 3-7637-5214-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Manstein, Erich (2004) [1955]. Powell, Anthony G (ed.). Lost Victories: The War Memoirs of Hitler's Most Brilliant General. St. Paul, MN: Zenith. ISBN 0-7603-2054-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - von Mellenthin, Friedrich W. (1955). Panzer Battles, 1939-1945: A Study of the Employment of Armour in the Second World War. London: Cassell. OCLC 7009406.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Megargee, Geoffrey P (2000). Inside Hitler's High Command. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1015-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Melvin, Mungo (2010). Manstein: Hitler's Greatest General. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson. ISBN 978-0-297-84561-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Müller, Rolf-Dieter; Uebershar, Gerd R (2002) [1997]. Hitler's War in the East: A Critical Assessment. New York: Berghahn. ISBN 978-1-57181-293-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nipe, George M. Jr. (2000). Last Victory in Russia: The SS-Panzerkorps and Manstein's Kharkov Counteroffensive, February–March 1943. Atglen, PA: Schiffer. ISBN 0-7643-1186-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Paget, Baron Reginald Thomas (1952). Manstein: Seine Feldzüge und sein Prozess (in German). Wiesbaden: Limes Verlag. OCLC 16731799.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Paget, Baron Reginald Thomas (1951). Manstein: His Campaigns and His Trial. London: Collins. OCLC 5582465.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stahlberg, Alexander (1990). Bounden Duty: The Memoirs of a German Officer, 1932–1945. London: Brassey's. ISBN 3-548-33129-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smelser, Ronald; Davies, Edward (2008). The Myth of the Eastern Front: The Nazi-Soviet War in American Popular Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-71231-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stein, Marcel (2007). The Janushead: Field Marshal Von Manstein, A Reappraisal. Solihill, West Midlands: Helion and Company. ISBN 1-906033-02-1.