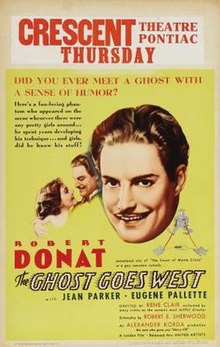

The Ghost Goes West

| The Ghost Goes West | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | René Clair |

| Screenplay by | Robert E. Sherwood (adaptation) Geoffrey Kerr (scenario) |

| Based on | the 1932 short story "Sir Tristram Goes West" by Eric Keown |

| Produced by | Alexander Korda |

| Starring | Robert Donat Jean Parker Eugene Pallette |

| Cinematography | Harold Rosson |

| Edited by | Henry Cornelius Harold Earle-Fishbacher |

| Music by | Mischa Spoliansky |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 80 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Box office | £158,039 (UK distributor)[1] |

The Ghost Goes West is a 1935 British romantic comedy/fantasy film directed by René Clair and starring Robert Donat, Jean Parker, and Eugene Pallette.[2] It was Clair's first English-language film. The story concerns an Old World ghost dealing with American materialism.

Plot

[edit]In 18th-century Scotland, Clan Glourie's enemy is Clan McLaggan, which is hated even more than the English. The McLaggan, the head of his clan, and his five sons go to fight the English. They pause at Glourie Castle to mock The Glourie and his clan as cowards. The outraged Glourie insists that one Glourie can thrash fifty McLaggans. The Glourie is too old and sick to fight, but he sends his only son Murdoch to the battle, even though Murdoch would rather spend his time kissing the lassies. At the Scottish encampment, Murdoch is outnumbered by the McLaggans and hides behind a barrel of gunpowder. An errant Scottish cannonball kills him, but in the afterlife he is stranded in Limbo due to his cowardice. His now-deceased father tells him he is doomed to haunt Glourie Castle until he can get a McLaggan to kneel and admit that one Glourie can thrash fifty McLaggans.

In the 20th century, Peggy Martin, the daughter of a rich American businessman, persuades her father to purchase Glourie Castle from Donald Glourie, who is besieged by his creditors. Donald agrees to sell for the £2,388 he owes, but is then outraged that Martin plans to dismantle his ancestral home and reassemble it in Florida; however, he is attracted to Peggy. Peggy meets the ghost of Murdoch on the castle battlements, but thinks he is Donald as they look exactly alike. Martin hires Donald to supervise the reconstruction in Florida, and along with the castle goes its ghost.

On the sea voyage to America, Donald has second thoughts, and he and Martin agree to cancel their deal. Martin's business rival, Ed Bigelow, sees a wonderful opportunity to publicize his products, and offers Donald $100,000 for the castle. Alarmed, Martin repurchases it for $150,000. Murdoch makes a spectral appearance before many witnesses, igniting a media frenzy, but Bigelow remains openly sceptical about the ghost. Murdoch's dalliances with other women, however, derail Donald's attempts at romance with Peggy, who still believes Murdoch is Donald.

In Florida, Martin hosts a lavish party to celebrate the castle's reassembly, but Murdoch refuses to make an appearance. Bigelow insults the Glouries during a radio broadcast, revealing he is a McLaggan on his mother's side. Murdoch chases him down and forces him to admit that one Glourie can thrash fifty McLaggans, and Murdoch is finally released to join his ancestors. Peggy, having realised her mistake, reconciles with Donald.

Cast

[edit]- Robert Donat as Murdoch Glourie and Donald Glourie

- Jean Parker as Peggy Martin

- Eugene Pallette as Mr. Martin

- Elsa Lanchester as Miss Shepperton

- Ralph Bunker as Ed. Bigelow

- Patricia Hilliard as shepherdess

- Everley Gregg as Mrs. Martin

- Morton Selten as The Glourie

- Chili Bouchier as Cleopatra

- Mark Daly as Murdoch's Groom

- Herbert Lomas as Fergus

- Elliott Mason as Mrs. MacNiff

- Hay Petrie as The McLaggan

- Quentin McPhearson as Mackaye

Background

[edit]The film is an adaptation of Eric Keown's short story "Sir Tristam Goes West", and was written by Robert E. Sherwood and Geoffrey Kerr, though Clair and Lajos Biro have been alleged by contemporary sources to have done uncredited writing on the screenplay.[3]

This was the first of two films Clair made in England following a deal he made with producer Alexander Korda, the other being his 1938 film Break the News.

Critical response

[edit]Writing for The Spectator in 1935, Graham Greene praised the film. He wrote of how the "camera sense" of René Clair manifested itself in the film's "feeling of mobility, of visual freedom" and highlighted Clair's directorial genius. Greene also praised the acting of Pallette and Donat, describing Pallette's portrayal of an American millionaire as the finest performance of his career, and Donat's acting style as imbued with "invincible naturalness".[4]

The Monthly Film Bulletin gave a mixed review: "If the continuity of the film appears in places rather thin, the satire occasionally a trifle obvious, and the humour sometimes a little mechanical, there are, nevertheless, some very good moments".[5]

Box office

[edit]The Ghost Goes West was the 13th most popular film at the British box office in 1935–36.[6] The film was voted the best British movie of 1936 by readers of Film Weekly magazine.[7] It was the most popular British film at the box office in 1936.[8]

Both the original treatment and the cutting continuity of the finished film were published in Successful Film Writing as Illustrated by 'The Ghost Goes West' by Seton Margrave. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1936, ASIN:B002A8VVQW.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ James Chapman ‘The Billings verdict’: Kine Weekly and the British Box Office, 1936–62' Journal of British Cinema and Television, Volume 20 Issue 2, Page 200-238, p 205

- ^ "The Ghost Goes West". British Film Institute Collections Search. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ Greene, Graham (27 December 1935). "The Ghost Goes West". The Spectator. (reprinted in: Taylor, John Russell, ed. (1980). The Pleasure Dome. pp. 40–41. ISBN 0192812866.)

- ^ "Ghost Goes West, The (1935)". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 2 (23). British Film Institute: 194–195. December 1935.

- ^ The Film Business in the United States and Britain during the 1930s by John Sedgwick and Michael Pokorny, The Economic History Review New Series, Vol. 58, No. 1 (Feb., 2005), pp. 97

- ^ "BEST FILM PERFORMANCE LAST YEAR". The Examiner (LATE NEWS EDITION and DAILY ed.). Launceston, Tasmania. 9 July 1937. p. 8. Retrieved 4 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ James Chapman ‘The Billings verdict’: Kine Weekly and the British Box Office, 1936–62' Journal of British Cinema and Television, Volume 20 Issue 2, Page 200-238, p 203

External links

[edit]- The Ghost Goes West at AllMovie

- The Ghost Goes West at the TCM Movie Database

- The Ghost Goes West at IMDb

- The Ghost Goes West at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- The Ghost Goes West on Screen Guild Theater: 21 August 1944

- 1935 films

- 1935 romantic comedy films

- 1930s historical comedy films

- 1930s fantasy comedy films

- 1930s ghost films

- British romantic comedy films

- British fantasy comedy films

- British black-and-white films

- British ghost films

- Films set in castles

- Films set in Scotland

- Films set in Florida

- Films set in the 18th century

- Films set in the 1930s

- London Films films

- Films directed by René Clair

- Films produced by Alexander Korda

- British historical comedy films

- British historical romance films

- British historical fantasy films

- 1930s British films

- Films scored by Mischa Spoliansky