Great Lakes Storm of 1913: Difference between revisions

m add missing punctuation |

SandyGeorgia (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

== Prelude== |

== Prelude== |

||

The storm was first noticed on Thursday November 6 on the western side of [[Lake Superior]], moving rapidly toward northern [[Lake Michigan]]. The weather forecast in ''[[The Detroit News]]'' predicted "moderate to brisk" winds at the Great Lakes with occasional rain on Thursday night or Friday for the upper lakes (except southern [[Lake Huron]]) and fair-to-unsettled conditions for the lower lakes.<ref>Weather forecast, ''The Detroit News'', Detroit, Michigan, 5 Nov 1913.</ref> Around midnight on |

The storm was first noticed on Thursday November 6 on the western side of [[Lake Superior]], moving rapidly toward northern [[Lake Michigan]]. The weather forecast in ''[[The Detroit News]]'' predicted "moderate to brisk" winds at the Great Lakes with occasional rain on Thursday night or Friday for the upper lakes (except southern [[Lake Huron]]) and fair-to-unsettled conditions for the lower lakes.<ref>Weather forecast, ''The Detroit News'', Detroit, Michigan, 5 Nov 1913.</ref> Around midnight on 6–7 November, the [[steamboat|steamer]] ''Cornell'', which was {{convert|50|mi|km}} west of [[Whitefish Point]] in Lake Superior, ran into a sudden northerly gale and was severely damaged. This gale lasted until late November 10 and almost forced ''Cornell'' ashore.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca//documents/1913Storm/default.asp?ID=s15 |title=Steamer Cornell Detailed Account Of Captain Noble's Experiences In Storm On Lake Superior, November 7th, 8th & 9th, 1913 |work=Maritime History of the Great Lakes |accessdate=June 8, 2021}}</ref> |

||

== Storm == |

== Storm == |

||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

=== November 8 === |

=== November 8 === |

||

By Saturday, the storm's status had been upgraded to "[[Severe weather|severe]]". At 10:00 a.m., [[United States Coast Guard|Coast Guard]] stations and [[United States Department of Agriculture]] (USDA) Weather Bureau offices at Lake Superior ports raised white [[maritime flags|pennants]] above square red flags with black centers, indicating a storm warning with northwesterly winds.{{sfn|Brown|2002|page=56}} The storm was centered over eastern Lake Superior, covering the entire lake basin. The weather forecast of the ''Port Huron Times-Herald'' stated southerly winds had remained "moderate to brisk".<ref>Front page, ''Port Huron Times-Herald'', Port Huron, Michigan, 8 November 1913.</ref> Northwesterly winds had reached gale strength on northern Lake Michigan and western Lake Superior.{{sfn|Brown|2002|page=59}} Gale wind flags were raised at more than a hundred ports but many captains continued their journeys. [[Lake freighter|Long ships]] traveled through the [[St. Marys River (Michigan–Ontario)|St. Marys River]] all that day, through the [[Straits of Mackinac]] all night, and up the [[Detroit River|Detroit]] and [[St. Clair River|St. Clair]] rivers early the following morning.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages= |

By Saturday, the storm's status had been upgraded to "[[Severe weather|severe]]". At 10:00 a.m., [[United States Coast Guard|Coast Guard]] stations and [[United States Department of Agriculture]] (USDA) Weather Bureau offices at Lake Superior ports raised white [[maritime flags|pennants]] above square red flags with black centers, indicating a storm warning with northwesterly winds.{{sfn|Brown|2002|page=56}} The storm was centered over eastern Lake Superior, covering the entire lake basin. The weather forecast of the ''Port Huron Times-Herald'' stated southerly winds had remained "moderate to brisk".<ref>Front page, ''Port Huron Times-Herald'', Port Huron, Michigan, 8 November 1913.</ref> Northwesterly winds had reached gale strength on northern Lake Michigan and western Lake Superior.{{sfn|Brown|2002|page=59}} Gale wind flags were raised at more than a hundred ports but many captains continued their journeys. [[Lake freighter|Long ships]] traveled through the [[St. Marys River (Michigan–Ontario)|St. Marys River]] all that day, through the [[Straits of Mackinac]] all night, and up the [[Detroit River|Detroit]] and [[St. Clair River|St. Clair]] rivers early the following morning.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages=44–67}} |

||

[[File:1913 Great Lakes storm wave.jpg|thumb|A wave breaking on the shore of [[Lake Michigan]] in [[Chicago]] while a man watches from a bridge|alt=See caption]] |

[[File:1913 Great Lakes storm wave.jpg|thumb|A wave breaking on the shore of [[Lake Michigan]] in [[Chicago]] while a man watches from a bridge|alt=See caption]] |

||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

By noon on Sunday, weather conditions on lower Lake Huron were close to normal for a November gale. [[Barometric pressure]]s in some areas began to rise, bringing hopes of an end to the storm. The [[low pressure area]] that had moved across Lake Superior was moving northeast, away from the lakes.{{sfn|Brown|2002|page=80}} The U.S. Weather Bureau issued the first of its twice-daily reports at approximately 8:00 a.m.; it did not send another report to [[Washington, D.C.]] until 8:00 p.m. This proved to be a serious problem; the storm would have most of the day to build up hurricane-force winds before the Bureau headquarters in Washington, D.C., would have detailed information.{{sfn|Brown|2002|page=80}}{{sfn|Brown|2002|page=12}} |

By noon on Sunday, weather conditions on lower Lake Huron were close to normal for a November gale. [[Barometric pressure]]s in some areas began to rise, bringing hopes of an end to the storm. The [[low pressure area]] that had moved across Lake Superior was moving northeast, away from the lakes.{{sfn|Brown|2002|page=80}} The U.S. Weather Bureau issued the first of its twice-daily reports at approximately 8:00 a.m.; it did not send another report to [[Washington, D.C.]] until 8:00 p.m. This proved to be a serious problem; the storm would have most of the day to build up hurricane-force winds before the Bureau headquarters in Washington, D.C., would have detailed information.{{sfn|Brown|2002|page=80}}{{sfn|Brown|2002|page=12}} |

||

Along southeastern Lake Erie near [[Erie, Pennsylvania]], a southern low-pressure area was moving toward the lake. This low had formed overnight so was absent from Friday's weather map. It had been moving northward but turned northwestward after passing over Washington, D.C.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages= |

Along southeastern Lake Erie near [[Erie, Pennsylvania]], a southern low-pressure area was moving toward the lake. This low had formed overnight so was absent from Friday's weather map. It had been moving northward but turned northwestward after passing over Washington, D.C.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages=99–101}} The low's intense, [[clockwise and counterclockwise|counterclockwise]] rotation was made apparent by the changing wind directions around its center. In [[Buffalo, New York]], morning northwest winds had shifted to the northeast by noon and to the southeast by 5:00 p.m., with gusts of up to {{convert|80|mph|kph|abbr=on}} occurring between 1:00 p.m. and 2:00 p.m. In [[Cleveland, Ohio]], {{convert|180|mi|km}} to the southwest, winds remained northwest during the day, shifting to the west by 5:00 p.m., and maintaining speeds of more than {{convert|50|mph|kph|abbr=on}}. The fastest gust in Cleveland, {{convert|79|mph|kph|abbr=on}}, occurred at 4:40 p.m. At Buffalo, barometric pressure dropped from 29.52 [[Pressure|inHg]] (999.7 [[hPa]]) at 8:00 a.m. to 28.77 inHg (974.3 hPa) at 8:00 p.m.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages=99–101}} |

||

[[File:DetroitNews-11-13-1913.png|thumb|''[[The Detroit News]]'' storm headlines, November 13, 1913|alt=The front page of a newspaper with the headline "Death Toll on Lakes May Be 273]] |

[[File:DetroitNews-11-13-1913.png|thumb|''[[The Detroit News]]'' storm headlines, November 13, 1913|alt=The front page of a newspaper with the headline "Death Toll on Lakes May Be 273]] |

||

The rotating low continued northward into the evening, bringing its counterclockwise winds in phase with the northwesterly winds already hitting Lakes Superior and Huron. This resulted in a dramatic increase in northerly wind speeds and swirling snow.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages= |

The rotating low continued northward into the evening, bringing its counterclockwise winds in phase with the northwesterly winds already hitting Lakes Superior and Huron. This resulted in a dramatic increase in northerly wind speeds and swirling snow.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages=99–101}} Ships on Lake Huron that were south of [[Alpena, Michigan]]—especially around [[Harbor Beach, Michigan|Harbor Beach]] and [[Port Huron, Michigan|Port Huron]] in [[Michigan]], and [[Goderich, Ontario|Goderich]] and [[Sarnia, Ontario|Sarnia]] in Ontario—experienced massive waves moving southward toward St. Clair River.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages=68–103}} Some ships sought shelter along the Michigan shore or between Goderich and Point Edward. Three of the larger ships were found upside down, indicating extremely high winds and tall waves.<ref name="Scott"/> From 8:00 p.m. to midnight, the storm became a "[[weather bomb]]" with sustained hurricane-speed winds of more than {{convert|70|mph|kph|abbr=on}} on the four western lakes. The worst damage was done on Lake Huron as ships sought shelter along its southern end. Gusts of {{convert|90|mph|kph|abbr=on}} were reported off Harbor Beach, Michigan. The lake's shape allowed northerly winds to increase unimpeded because water has less [[surface friction]] than land and because the wind followed the lake's length.{{sfn|Brown|2002|page=101}} |

||

Weather forecasters of the time did not have enough data or understanding of atmospheric dynamics to predict or comprehend the events of Sunday November 9. [[Weather front|Frontal]] mechanisms, which were then referred to as "squall lines", were not yet understood. Surface observations were only collected twice daily at stations around the country; by the time these data were collected and maps were hand-drawn, the information was no longer representative of the actual weather conditions.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages=13, 19, 68}} |

Weather forecasters of the time did not have enough data or understanding of atmospheric dynamics to predict or comprehend the events of Sunday November 9. [[Weather front|Frontal]] mechanisms, which were then referred to as "squall lines", were not yet understood. Surface observations were only collected twice daily at stations around the country; by the time these data were collected and maps were hand-drawn, the information was no longer representative of the actual weather conditions.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages=13, 19, 68}} |

||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

[[File:Charles S Price upside down, 1913.png|thumb|The {{convert|504|ft|m|abbr=on}} ''Charles S. Price'', upside down on the southern end of Lake Huron|alt=See caption]] |

[[File:Charles S Price upside down, 1913.png|thumb|The {{convert|504|ft|m|abbr=on}} ''Charles S. Price'', upside down on the southern end of Lake Huron|alt=See caption]] |

||

The greatest damage was done on the lakes. Major shipwrecks occurred on all but Lake Ontario, with most happening on southern and western Lake Huron. [[Lake master]]s said waves reached at least {{convert|35|ft|m|abbr=on}} in height.{{sfn|Brown|2002|page=223}} These waves were shorter than waves usually formed by gales and occurred in rapid succession. Rocky shores prevalent on the Great Lakes reflect rather than absorb waves. Reflected waves can combine with incoming waves to create [[rogue wave]]s of up to {{Convert|50|ft|m|abbr=on}}. Captains said the phenomenon combines waves into trios of rogue waves called "Three Sisters"; Lake Superior is noted for having them.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages= |

The greatest damage was done on the lakes. Major shipwrecks occurred on all but Lake Ontario, with most happening on southern and western Lake Huron. [[Lake master]]s said waves reached at least {{convert|35|ft|m|abbr=on}} in height.{{sfn|Brown|2002|page=223}} These waves were shorter than waves usually formed by gales and occurred in rapid succession. Rocky shores prevalent on the Great Lakes reflect rather than absorb waves. Reflected waves can combine with incoming waves to create [[rogue wave]]s of up to {{Convert|50|ft|m|abbr=on}}. Captains said the phenomenon combines waves into trios of rogue waves called "Three Sisters"; Lake Superior is noted for having them.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages=47–48}} |

||

In the late afternoon of November 10, an unknown vessel was spotted floating upside-down in about {{convert|60|ft|m}} of water on the eastern coast of Michigan within sight of [[Huronia Beach]] and the mouth of the St. Clair River. Determining the identity of this "mystery ship" became a national interest, resulting in daily front-page newspaper articles. The ship eventually sank and was identified on November 15 as ''Charles S. Price''.{{sfn|Minnich|1989|page=218}} The front page of that day's ''Port Huron Times-Herald'' extra edition read: "BOAT IS PRICE —DIVER IS BAKER — SECRET KNOWN".<ref>Front page, ''Port Huron Times-Herald'' EXTRA edition, Port Huron, Michigan, 15 November 1913.</ref> Milton Smith, an assistant engineer who decided at the last moment not to join his crew on premonition of disaster, helped identify bodies from the wreck.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages= |

In the late afternoon of November 10, an unknown vessel was spotted floating upside-down in about {{convert|60|ft|m}} of water on the eastern coast of Michigan within sight of [[Huronia Beach]] and the mouth of the St. Clair River. Determining the identity of this "mystery ship" became a national interest, resulting in daily front-page newspaper articles. The ship eventually sank and was identified on November 15 as ''Charles S. Price''.{{sfn|Minnich|1989|page=218}} The front page of that day's ''Port Huron Times-Herald'' extra edition read: "BOAT IS PRICE —DIVER IS BAKER — SECRET KNOWN".<ref>Front page, ''Port Huron Times-Herald'' EXTRA edition, Port Huron, Michigan, 15 November 1913.</ref> Milton Smith, an assistant engineer who decided at the last moment not to join his crew on premonition of disaster, helped identify bodies from the wreck.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages=196–199}} Among the debris cast up by the storm was the wreckage of the fish tug ''Searchlight'', which was lost in April 1907.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.gendisasters.com/michigan/16028/harbor-beach-mi-lake-huron-fishing-tug-searchlight-lost-apr-1907 |title=Harbor Beach, MI (Lake Huron) Fishing Tug Searchlight Lost, Apr 1907 |newspaper=[[Daily Chronicle (Michigan)|Daily Chronicle]] |location=Marshall, Michigan |date=25 April 1907 |access-date=19 July 2019| via=Gendisasters.com}}</ref> |

||

The final tally of financial loss included [[United States dollar|US$]]2,332,000 for totally lost vessels, $830,900 for vessels that became constructive total losses, $620,000 for vessels stranded but returned to service, and approximately $1,000,000 in lost cargoes. This figure excludes financial losses in coastal cities.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages=245}} |

The final tally of financial loss included [[United States dollar|US$]]2,332,000 for totally lost vessels, $830,900 for vessels that became constructive total losses, $620,000 for vessels stranded but returned to service, and approximately $1,000,000 in lost cargoes. This figure excludes financial losses in coastal cities.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages=245}} |

||

While the storm was the main cause of damage on the lakes, human factors, including measures that could have reduced the storm's effects but were not taken, also contributed to it. Post-storm conversations mostly focused on placing blame but served to highlight weaknesses.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages= |

While the storm was the main cause of damage on the lakes, human factors, including measures that could have reduced the storm's effects but were not taken, also contributed to it. Post-storm conversations mostly focused on placing blame but served to highlight weaknesses.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages=205–226}} The U.S. Weather Bureau did not have enough data – including upper atmospheric data – communications and analysis capability, or understanding of atmospheric dynamics to predict the storm, including predicting wind directions to allow ships to avoid or cope with the effects of the storm. The bureau hesitated to admit its limitations because it wanted to secure higher budgets. Instead, it focused on the terminology and nature of warnings.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages=205–210}} Another factor was the underpowering of large ships that affected their ability to travel, maneuver, and hold steady in severe storms. For example, the {{Convert|504|foot|meter|abbr=out|adj=on}} ''Charles S. Price'' had a single 1,760 horsepower engine. Even with both anchors dropped and steaming full power into the wind, it was unable to avoid being carried backward. Three years after the storm, the same shipyard built a {{convert|587|ft|m|adj=mid|-long}} freighter with only 1,800 horsepower.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages=217–219}} |

||

The geometry of the lakes and locks combined with operational economics dictated the use of slimmer, shallower ships than comparable ocean-going vessels, reducing stability and structural strength.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages= |

The geometry of the lakes and locks combined with operational economics dictated the use of slimmer, shallower ships than comparable ocean-going vessels, reducing stability and structural strength.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages=221–222}} Also noted was the insufficient strength of the large hatches and their fastenings, and the shortness of the {{Convert|12|inch|cm|abbr=on}} hatch [[coaming]]s.{{sfn|Brown|2002|page=221}} The limited compartmentalization of cargo holds meant the flooding of one compartment was sufficient to sink the ship.{{sfn|Brown|2002|page=195}} The practice of not "[[Bulk carrier#Stability problems|trimming]]" or leveling the pyramid-shape piles of bulk solid cargo<ref name = trimming>https://www.google.com/books/edition/Cargo_Handling_and_Stowage/Q1ofCwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%27trimming+of+cargo%22&pg=PA120&printsec=frontcover ''Cargo handling and stowage'' by Peter Grunau retrieved 8/9/21 </ref> made them more prone to shifting and causing a capsize.{{sfn|Brown|2002|page=220}} Author David Brown noted concerns that the practice of shipping companies incentivizing or possibly even pressuring captains to sail during the dangerous November season or during dangerous weather were raised at the time and continued, including 62 years later after the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald.{{sfn|Brown|2002|page=215}} Few of these factors were acted upon.<ref name = schumacher> ''The Deadly Great Lakes Hurricane of 1913 Noverber's Fury'' by Michael Schumacher University of Minnesota Press 2013 ISBN 978-o-8166-8719-0 ISBN 978-o-8166-8720-6 oclc 862614685 </ref> One change was that the weather service clarified their previous ambiguity and said that they would post a higher-than-gale level warning for even more severe predicted storms.{{sfn|Brown|2002|pages=217–221}} |

||

== Ships foundered == |

== Ships foundered == |

||

Revision as of 00:13, 1 November 2021

Convergence of systems to form a typical November gale | |

| Type | Extratropical cyclone Winter storm Blizzard |

|---|---|

| Formed | November 6, 1913 |

| Dissipated | November 11, 1913 |

| Highest gust | 90 mph (150 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 968.5 mb (28.60 inHg) |

| Maximum snowfall or ice accretion | 24 in (61 cm) |

| Fatalities | over 250 |

| Damage |

|

| Areas affected | The Great Lakes Basin in the Midwestern United States and the Canadian province of Ontario |

The Great Lakes Storm of 1913, which was historically referred to as the "Big Blow",[1][A] the "Freshwater Fury", and the "White Hurricane", was a blizzard with hurricane-force winds that devastated the Great Lakes Basin in the Midwestern United States and Southwestern Ontario, Canada, from November 7 to 10, 1913. The storm was most powerful on November 9, battering and overturning ships on four of the five Great Lakes, particularly Lake Huron.

The storm was the deadliest, most destructive natural disaster in recorded history to hit the lakes. The Great Lakes Storm killed more than 250 people, destroyed 19 ships, and stranded 19 others. About $1 million of cargo—including coal, iron ore, and grain—weighing about 68,300 tons was lost. While shipping was the hardest hit in the storm, it impacted other cities including Duluth, Chicago, and Cleveland, the latter of which received feet of snow and was paralyzed for days.

The extratropical cyclone originated when two major storm fronts that were fueled by the lakes' relatively warm waters—a seasonal process called a "November gale"—converged. It produced wind gusts of 90 mph (140 km/h), waves over 35 feet (11 m) high, and whiteout snowsqualls. Rogue waves and clapotis are both known to occur on the Great Lakes and can result in the loss of ships. Winds exceeding hurricane force occurred over four of the Great Lakes for extended periods creating very large waves.

The U.S. Weather Bureau failed to predict the intensity of the storm, and the process of preparing and communicating predictions was slow. These factors contributed to the storm's destructiveness.[2] The contemporaneous weather forecasters did not have enough data, communications, analysis capability, and understanding of atmospheric dynamics to predict the storm. They could not predict wind directions, which is key to the ability of ships to avoid or cope with the effects of storms.

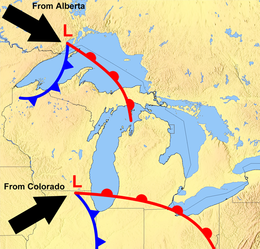

Background

The water in the five Great Lakes holds heat that allows them to remain relatively warm late into the year and postpones the Arctic spread in the region.[3] During the autumn, two major weather tracks converge over the area. Cold, dry air moves south and southeast from Alberta and northern Canada as an Alberta clipper while warm, moist air moves north and northeast from the Gulf of Mexico along the lee of the central Rocky Mountains as a Colorado low. The collision of these air masses forms large storm systems in the middle of the North American continent, including the Great Lakes.[3] When the cold air from these storms moves over the lakes, it is warmed by the waters below[4] and picks up a spin.[3] As the cyclonic system continues over the lakes, its power is intensified by the jet stream above and the warm waters below.[3][5]

The resulting storm, which is commonly called a "November gale" or "November witch", can maintain hurricane-force wind gusts, produce waves over 50 feet (15 m) high, and dump significant falls of rain or snow. Fueled by the warm lake water, these powerful storms may remain over the Great Lakes for days.[3] Intense winds affect the lakes and shorelines, causing erosion and flooding.[6][7][8]

November gales have caused several large storms over the Great Lakes, with at least 25 killer storms affecting the region since 1847.[3] During the Mataafa Storm in 1905, 27 wooden vessels were lost. During a November gale in 1975, the giant bulk carrier SS Edmund Fitzgerald sank suddenly without sending a distress signal and with all crew still on board.[4][9] Rogue waves and clapotis are both known to occur on the Great Lakes and can result in the loss of ships.[B]

Prelude

The storm was first noticed on Thursday November 6 on the western side of Lake Superior, moving rapidly toward northern Lake Michigan. The weather forecast in The Detroit News predicted "moderate to brisk" winds at the Great Lakes with occasional rain on Thursday night or Friday for the upper lakes (except southern Lake Huron) and fair-to-unsettled conditions for the lower lakes.[12] Around midnight on 6–7 November, the steamer Cornell, which was 50 miles (80 km) west of Whitefish Point in Lake Superior, ran into a sudden northerly gale and was severely damaged. This gale lasted until late November 10 and almost forced Cornell ashore.[13]

Storm

At the time the U.S. Weather Bureau did not have enough data, communications, analysis capability, and understanding of atmospheric dynamics to understand or predict the storm. Studies of the available information and data from the storm have been done in more modern times enabling a description of the weather mechanisms of the storm.[2] Those reveal that it was actually two storms. By November 7th a string of low pressure centers in Canada had consolidated into a low pressure center southwest of Lake Superior which became "Storm #1". At the same time warm air pushed into the central Great Lakes from the south.[14] By November 8th this storm was moving east through northern Lake Huron while strong northerly winds developed behind it over Lake Superior. By November 9th Storm #2 had formed over the Carolinas and Virginia. The northern portion of this storm began sweeping warm moist Atlantic air over colder air in the Ohio area producing heavy snows.[14] The northwest portion of this extremely powerful storm began creating strong winds from the North along the long axis of Lake Huron building large waves. By November 10th, 24 hours of such building had created immense waves which ships were subjected to along with the high winds. At this time the center of the storm crossed north/northwest over Lake Erie near Toronto.[14] Surface pressures in this storm went went as low as 968.5 millibars, the lowest of the 1913 storm.[14][15] Winds exceeding hurricane force occurred over four of the Great Lakes for extended periods.[5]

November 7

On Friday, the weather forecast in the Port Huron Times-Herald of Port Huron, Michigan, described the storm as "moderately severe".[16] The forecast predicted increased winds and falling temperatures over the next 24 hours.[16] At 10:00 a.m., Coast Guard stations and all 112 United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Weather Bureau signal stations on the Great Lakes received a directive to hoist a square, red, signal flag with a black center and a red, triangular, maritime pennant below it, indicating a storm with winds of 55 mph (89 km/h) that would blow from the southwest.[17] After dark, a red lantern over a white one was displayed to warn of storm winds from the west.[17] The winds on Lake Superior had already reached 60 mph (97 km/h) with gusts to 80 mph (130 km/h) and an accompanying blizzard was moving toward Lake Huron.[18] Sustained wind speeds reached 62 mph (100 km/h) and gusts to 68 mph (109 km/h) at Duluth, Minnesota.[19]

November 8

By Saturday, the storm's status had been upgraded to "severe". At 10:00 a.m., Coast Guard stations and United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Weather Bureau offices at Lake Superior ports raised white pennants above square red flags with black centers, indicating a storm warning with northwesterly winds.[20] The storm was centered over eastern Lake Superior, covering the entire lake basin. The weather forecast of the Port Huron Times-Herald stated southerly winds had remained "moderate to brisk".[21] Northwesterly winds had reached gale strength on northern Lake Michigan and western Lake Superior.[22] Gale wind flags were raised at more than a hundred ports but many captains continued their journeys. Long ships traveled through the St. Marys River all that day, through the Straits of Mackinac all night, and up the Detroit and St. Clair rivers early the following morning.[23]

November 9

By noon on Sunday, weather conditions on lower Lake Huron were close to normal for a November gale. Barometric pressures in some areas began to rise, bringing hopes of an end to the storm. The low pressure area that had moved across Lake Superior was moving northeast, away from the lakes.[24] The U.S. Weather Bureau issued the first of its twice-daily reports at approximately 8:00 a.m.; it did not send another report to Washington, D.C. until 8:00 p.m. This proved to be a serious problem; the storm would have most of the day to build up hurricane-force winds before the Bureau headquarters in Washington, D.C., would have detailed information.[24][25]

Along southeastern Lake Erie near Erie, Pennsylvania, a southern low-pressure area was moving toward the lake. This low had formed overnight so was absent from Friday's weather map. It had been moving northward but turned northwestward after passing over Washington, D.C.[26] The low's intense, counterclockwise rotation was made apparent by the changing wind directions around its center. In Buffalo, New York, morning northwest winds had shifted to the northeast by noon and to the southeast by 5:00 p.m., with gusts of up to 80 mph (130 km/h) occurring between 1:00 p.m. and 2:00 p.m. In Cleveland, Ohio, 180 miles (290 km) to the southwest, winds remained northwest during the day, shifting to the west by 5:00 p.m., and maintaining speeds of more than 50 mph (80 km/h). The fastest gust in Cleveland, 79 mph (127 km/h), occurred at 4:40 p.m. At Buffalo, barometric pressure dropped from 29.52 inHg (999.7 hPa) at 8:00 a.m. to 28.77 inHg (974.3 hPa) at 8:00 p.m.[26]

The rotating low continued northward into the evening, bringing its counterclockwise winds in phase with the northwesterly winds already hitting Lakes Superior and Huron. This resulted in a dramatic increase in northerly wind speeds and swirling snow.[26] Ships on Lake Huron that were south of Alpena, Michigan—especially around Harbor Beach and Port Huron in Michigan, and Goderich and Sarnia in Ontario—experienced massive waves moving southward toward St. Clair River.[27] Some ships sought shelter along the Michigan shore or between Goderich and Point Edward. Three of the larger ships were found upside down, indicating extremely high winds and tall waves.[2] From 8:00 p.m. to midnight, the storm became a "weather bomb" with sustained hurricane-speed winds of more than 70 mph (110 km/h) on the four western lakes. The worst damage was done on Lake Huron as ships sought shelter along its southern end. Gusts of 90 mph (140 km/h) were reported off Harbor Beach, Michigan. The lake's shape allowed northerly winds to increase unimpeded because water has less surface friction than land and because the wind followed the lake's length.[28]

Weather forecasters of the time did not have enough data or understanding of atmospheric dynamics to predict or comprehend the events of Sunday November 9. Frontal mechanisms, which were then referred to as "squall lines", were not yet understood. Surface observations were only collected twice daily at stations around the country; by the time these data were collected and maps were hand-drawn, the information was no longer representative of the actual weather conditions.[29]

November 10 and 11

On Monday November 10, morning, the storm had moved northeast of London, Ontario, with lake effect blizzards behind it. An additional 17 inches (43 cm) of snow fell on Cleveland, Ohio, that day, filling the streets with snowdrifts 6 feet (1.8 m) high. Streetcar operators stayed with their stranded, powerless vehicles for two nights, eating food provided by local residents. Travelers were forced to take shelter and wait for the storm to pass.[30]

By Tuesday, the storm was rapidly moving across eastern Canada. Without the warm lake waters, it quickly lost strength. the system carried less snowfall because of its speed and the lack of lake effect snow.[31] All shipping along the St. Lawrence River around Montreal, Quebec, was halted on Monday and part of Tuesday.[31]

Aftermath

The storm was the deadliest, most destructive natural disaster in recorded history to hit the lakes.[32] The Great Lakes Storm killed more than 250 people,[33][34] destroyed 19 ships and stranded 19 others. About $1 million of cargo—including coal, iron ore, and grain—weighing about 68,300 tons was lost.[35]

Surrounding shoreline

Along the shoreline, blizzards stopped traffic and communication, causing hundreds of thousands of dollars in damage. A 22-inch (56 cm) snowfall in Cleveland, Ohio, closed stores for two days. There were four-foot (120 cm) snowdrifts around Lake Huron. Electricity supply was cut for several days across Michigan and Ontario, cutting off telephone and telegraph communications. A recently completed US$100,000 breakwater at Chicago, which was intended to protect the Lincoln Park basin from storms, was swept away in a few hours.[36] The Milwaukee, Wisconsin, harbor lost its south breakwater and much of the surrounding South Park area that had been recently renovated.[37]

After the final blizzards hit Cleveland, the city was paralyzed under feet of ice and snow, and was without power for days. Telephone poles were broken and power cables lay in tangled masses. Nearly all rail traffic was halted for days. The November 11 Plain Dealer described the aftermath: "Cleveland lay in white and mighty solitude, mute and deaf to the outside world, a city of lonesome snowiness, storm-swept from end to end, when the violence of the two-day blizzard lessened late yesterday afternoon".[C]

William H. Alexander, Cleveland's chief weather forecaster, commented:

Take it all in all—the depth of the snowfall, the tremendous wind, the amount of damage done and the total unpreparedness of the people—I think it is safe to say that the present storm is the worst experienced in Cleveland during the whole forty-three years the U.S. Weather Bureau has been established in the city.[D]

Immediately following the blizzard in Cleveland, the city began a campaign to move all utility cables underground in tubes beneath major streets. The project took five years.[38]

On the lakes

The greatest damage was done on the lakes. Major shipwrecks occurred on all but Lake Ontario, with most happening on southern and western Lake Huron. Lake masters said waves reached at least 35 ft (11 m) in height.[39] These waves were shorter than waves usually formed by gales and occurred in rapid succession. Rocky shores prevalent on the Great Lakes reflect rather than absorb waves. Reflected waves can combine with incoming waves to create rogue waves of up to 50 ft (15 m). Captains said the phenomenon combines waves into trios of rogue waves called "Three Sisters"; Lake Superior is noted for having them.[40]

In the late afternoon of November 10, an unknown vessel was spotted floating upside-down in about 60 feet (18 m) of water on the eastern coast of Michigan within sight of Huronia Beach and the mouth of the St. Clair River. Determining the identity of this "mystery ship" became a national interest, resulting in daily front-page newspaper articles. The ship eventually sank and was identified on November 15 as Charles S. Price.[41] The front page of that day's Port Huron Times-Herald extra edition read: "BOAT IS PRICE —DIVER IS BAKER — SECRET KNOWN".[42] Milton Smith, an assistant engineer who decided at the last moment not to join his crew on premonition of disaster, helped identify bodies from the wreck.[43] Among the debris cast up by the storm was the wreckage of the fish tug Searchlight, which was lost in April 1907.[44]

The final tally of financial loss included US$2,332,000 for totally lost vessels, $830,900 for vessels that became constructive total losses, $620,000 for vessels stranded but returned to service, and approximately $1,000,000 in lost cargoes. This figure excludes financial losses in coastal cities.[45]

While the storm was the main cause of damage on the lakes, human factors, including measures that could have reduced the storm's effects but were not taken, also contributed to it. Post-storm conversations mostly focused on placing blame but served to highlight weaknesses.[46] The U.S. Weather Bureau did not have enough data – including upper atmospheric data – communications and analysis capability, or understanding of atmospheric dynamics to predict the storm, including predicting wind directions to allow ships to avoid or cope with the effects of the storm. The bureau hesitated to admit its limitations because it wanted to secure higher budgets. Instead, it focused on the terminology and nature of warnings.[47] Another factor was the underpowering of large ships that affected their ability to travel, maneuver, and hold steady in severe storms. For example, the 504-foot (154 m) Charles S. Price had a single 1,760 horsepower engine. Even with both anchors dropped and steaming full power into the wind, it was unable to avoid being carried backward. Three years after the storm, the same shipyard built a 587-foot-long (179 m) freighter with only 1,800 horsepower.[48]

The geometry of the lakes and locks combined with operational economics dictated the use of slimmer, shallower ships than comparable ocean-going vessels, reducing stability and structural strength.[49] Also noted was the insufficient strength of the large hatches and their fastenings, and the shortness of the 12 in (30 cm) hatch coamings.[50] The limited compartmentalization of cargo holds meant the flooding of one compartment was sufficient to sink the ship.[51] The practice of not "trimming" or leveling the pyramid-shape piles of bulk solid cargo[52] made them more prone to shifting and causing a capsize.[53] Author David Brown noted concerns that the practice of shipping companies incentivizing or possibly even pressuring captains to sail during the dangerous November season or during dangerous weather were raised at the time and continued, including 62 years later after the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald.[54] Few of these factors were acted upon.[55] One change was that the weather service clarified their previous ambiguity and said that they would post a higher-than-gale level warning for even more severe predicted storms.[56]

Ships foundered

The following list includes ships (in order of number of victims) that sank during the storm, killing their entire crews. It does not include the three victims from the freighter William Nottingham, who volunteered to leave the ship on a lifeboat in search of assistance.[E] The following shipwreck casualties have been documented:[39]

| Name | Body of water | Number of victims | Year located | Coordinates | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isaac M. Scott | Lake Huron | 28[57] | 1976[58] | 45°03′55″N 83°02′21″W / 45.065333°N 83.039217°W |

|

| Charles S. Price | Lake Huron | 28[57] | 1913[58] | 43°09′10″N 82°21′10″W / 43.1529°N 82.3529°W |

|

| Argus | Lake Huron | 28[57] | 1972[58] | 44°26′00″N 82°48′00″W / 44.433333°N 82.8°W |

|

| Henry B. Smith | Lake Superior | 23[57] | 2013[59][58] | 46°54′50″N 87°19′59″W / 46.914°N 87.333°W |

|

| Hydrus | Lake Huron | 25[57] | 2015[60] | 43°17′00″N 82°26′00″W / 43.283333°N 82.433333°W |

|

| John A. McGean | Lake Huron | 28[57] | 1985[58] | 43°57′12″N 82°31′43″W / 43.953267°N 82.528617°W |

|

| James Carruthers | Lake Huron | 22[57] | Not located | _ |

|

| Regina | Lake Huron | 20[57] | 1986[61] | 43°20′14″N 82°26′46″W / 43.337333°N 82.446°W |

|

| Wexford | Lake Huron | 20[57] | 2000[58] | 43°25′00″N 81°55′00″W / 43.416667°N 81.916667°W |

|

| Leafield | Lake Superior | 18[57] | Not located | _ |

|

| Plymouth | Lake Michigan | 7[57] | Not located | _ |

|

| LV-82 Buffalo | Lake Erie | 6[62][57] | 1914[58] | Raised and later scrapped |

|

See also

- List of storms on the Great Lakes

- Shipwrecks of the 1913 Great Lakes storm

- List of lighthouses in Ontario

References

Notes

- ^ Another storm called the "Big Blow" was on October 15, 1880, which sank the SS Alpena

- ^ Due to the lower density of fresh water compared to salt-rich sea water,[10] waves on the Great Lakes can be taller and shorter, thus steeper – the height-to-length ratio of the wave – than ocean waves; a phenomenon called "haystacking".[11]

- ^ Reprinted in [38]

- ^ Reprinted in [31]

- ^ While the boat was being lowered into the water, a breaking wave smashed it into the side of the ship. The men disappeared into the near-freezing waters below.

Citations

- ^ Brown 2002, p. 201.

- ^ a b c Scott, Chris (November 10, 2014). "The White Hurricane: The worst storm in Great Lakes history". Weather Network News. The Weather Network. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

The Great Storm of 1913, known as the 'White Hurricane'

- ^ a b c d e f Heidorn, Keith C. (2001). "The Great Lakes: Storm Breeding Ground". Science of the Sky. Published online 16 Nov 2001, Suite101. Retrieved 5 February 2005.

- ^ a b Bentley, Mace. Horstmeyer, Steve. "The witch of November." Weatherwise Magazine. November/December, 1998. doi:10.1080/00431672.1998.9926174.

- ^ a b https://www.weather.gov/media/greatlakes/1913Retrospective.pdf The White Hurricane Storm of 1913 A Numerical Model Retrospective by Richard Wagenmaker NWS Detroit & Dr. Greg Mann NWS Detroit Retrieved 8/28/21

- ^ Hemming 1992.

- ^ Ratigan 1987.

- ^ Shipley & Addis 1992.

- ^ Brown 2002, p. 246.

- ^ 3.2 The density of fresh water and seawater Open Learning

- ^ Rogue Waves National Geographic

- ^ Weather forecast, The Detroit News, Detroit, Michigan, 5 Nov 1913.

- ^ "Steamer Cornell Detailed Account Of Captain Noble's Experiences In Storm On Lake Superior, November 7th, 8th & 9th, 1913". Maritime History of the Great Lakes. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c d https://www.weather.gov/media/apx/spotter/1913Storm.pdf Great Lakes Hurricane of 1913: A Meteorological Review 100 Years Later National Weather Service Gaylord MI Winter Talk Series 2013 Retrieved 10/29/21

- ^ https://www.weather.gov/dtx/strm_1913 Snowstorms National Weather Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Retrieved October 30, 2021

- ^ a b Front page,The Weather Port Huron Times-Herald, Port Huron, Michigan. 7 November 1913.

- ^ a b Brown 2002, p. 33-34.

- ^ Brown 2002, p. 40.

- ^ Brown 2002, p. 38.

- ^ Brown 2002, p. 56.

- ^ Front page, Port Huron Times-Herald, Port Huron, Michigan, 8 November 1913.

- ^ Brown 2002, p. 59.

- ^ Brown 2002, pp. 44–67.

- ^ a b Brown 2002, p. 80.

- ^ Brown 2002, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Brown 2002, pp. 99–101.

- ^ Brown 2002, pp. 68–103.

- ^ Brown 2002, p. 101.

- ^ Brown 2002, pp. 13, 19, 68.

- ^ Brown 2002, p. 127.

- ^ a b c Brown 2002, p. 163.

- ^ Brown 2002, pp. 208, 222.

- ^ Brown 2002, pp. xvii.

- ^ Annual Report of the Lake Carriers' Association. 1913.

- ^ Brown 2002, pp. 203, 225.

- ^ Brown 2002, pp. 94.

- ^ Barcus 1986, p. 6.

- ^ a b Brown 2002, p. 162.

- ^ a b Brown 2002, p. 223.

- ^ Brown 2002, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Minnich 1989, p. 218.

- ^ Front page, Port Huron Times-Herald EXTRA edition, Port Huron, Michigan, 15 November 1913.

- ^ Brown 2002, pp. 196–199.

- ^ "Harbor Beach, MI (Lake Huron) Fishing Tug Searchlight Lost, Apr 1907". Daily Chronicle. Marshall, Michigan. 25 April 1907. Retrieved 19 July 2019 – via Gendisasters.com.

- ^ Brown 2002, pp. 245.

- ^ Brown 2002, pp. 205–226.

- ^ Brown 2002, pp. 205–210.

- ^ Brown 2002, pp. 217–219.

- ^ Brown 2002, pp. 221–222.

- ^ Brown 2002, p. 221.

- ^ Brown 2002, p. 195.

- ^ https://www.google.com/books/edition/Cargo_Handling_and_Stowage/Q1ofCwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%27trimming+of+cargo%22&pg=PA120&printsec=frontcover Cargo handling and stowage by Peter Grunau retrieved 8/9/21

- ^ Brown 2002, p. 220.

- ^ Brown 2002, p. 215.

- ^ The Deadly Great Lakes Hurricane of 1913 Noverber's Fury by Michael Schumacher University of Minnesota Press 2013 ISBN 978-o-8166-8719-0 ISBN 978-o-8166-8720-6 oclc 862614685

- ^ Brown 2002, pp. 217–221.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Brown 2002, p. 203.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Shipwrecks of the 1913 storm". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ Krueger, Andrew (June 9, 2013). "100 years after ore boat disappeared in Lake Superior storm, searchers locate wreck". Duluth News Tribune. Archived from the original on June 10, 2013.

- ^ Schaefer, Jim (November 9, 2015). "Man discovers Lake Huron shipwreck missing since 1913". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved 2015-11-09.

- ^ "History & Salvage of the SS Regina". Shipwrecks.com. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ Vogel, Michael N.; Redding, Paul F. "Maritime Buffalo, Buffalo History, Lightship LV 82". Archived from the original on Mar 5, 2016.

References

- Barcus, Frank (1986). Freshwater Fury: Yarns and Reminiscences of the Greatest Storm in Inland Navigation. Wayne State University Press. p. 166. ISBN 0-8143-1828-2.

- Brown, David G. (2002). White Hurricane: A Great Lakes November Gale and America's Deadliest Maritime Disaster. International Marine/ McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-138037-X.

- Hemming, Robert J. (1992). Ships Gone Missing: The Great Lakes Storm of 1913. Chicago: Contemporary Books, Inc. ISBN 0-8092-3909-4.

- Minnich, Jerry (1989). The Wisconsin Almanac: being a loosely organized compendium of facts, history, lore, remembrances, puzzles, recipes, and both household and gardening advice with which to offer elucidation, assistance, and occasional amusement to the conscientious reader. Madison, Wisconsin: North Country Press. p. 218. ISBN 0-944133-06-1.

- Ratigan, William (1987). Great Lakes Shipwrecks and Survivals. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. ISBN 0-8028-7010-4.

- Shipley, Robert; Addis, Fred (1992). Wrecks and Disasters: Great Lakes Album Series. St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada: Vanwell Publishing Limited. ISBN 0-920277-77-2.

- Articles in The Port Huron Times-Herald. Port Huron, Michigan. (Nov. 10–15, 1913). various authors and pages. Transcripts of relevant articles are available online.

External links

- A first-person account of the storm, from a 1914 article in the Marine Review.

- The Wexford: Elusive Shipwreck of the 1913 Great Storm.

- List of victims of the 1913 Great Lakes storm @ rootsweb.com.

- Personal experiences of Captains of the Lake Fleet.

- Photos of various discovered shipwrecks.

- Tales of sea and riverside, Great Storm of 1913 (pictures of all the ships lost.)

- The Great Blizzard of 1978, details the cause of the November gale.

- "Isaac M. Scott". Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary and Underwater Preserve. Retrieved February 10, 2005.

- GenDisasters.com; Great Lake Locations: "Great Gale of 1913" (Nov 1913)