Islam and democracy: Difference between revisions

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

=== Sunni viewpoint === |

=== Sunni viewpoint === |

||

Sunnis believe that after the Prophet Muhammad, no one has direct access to God’s will, and therefore no one person or group has the legitimacy or authority to claim a pope- or priesthood-like status in the Muslim community. Therefore the democratic ideal of a “government by the people” is compatible with the notion of an Islamic democracy. Muslims often refer to the system by which the first four ("Rightly Guided") [[caliph]]s were chosen, using a traditional Arab mechanism of consultation. While these deliberations were not democratic in |

Sunnis believe that after the Prophet Muhammad, no one has direct access to God’s will, and therefore no one person or group has the legitimacy or authority to claim a pope- or priesthood-like status in the Muslim community. Therefore the democratic ideal of a “government by the people” is compatible with the notion of an Islamic democracy. Muslims often refer to the system by which the first four ("Rightly Guided") [[caliph]]s were chosen, using a traditional Arab mechanism of consultation. While these deliberations were not democratic in the modern sense (rather, decision-making power lay with a council of notables or clan patriarchs), they show that some appeals to popular consent are permissible (though not necessarily required) within Islam.<ref>Sohaib N. Sultan, [http://www.islamonline.net/English/introducingislam/politics/Politics/article04.shtml Forming an Islamic Democracy]</ref> (See also: [[Shura]]). |

||

In the early Islamic [[Caliphate]], the head of state, the [[Caliph]], had a position based on the notion of a successor to [[Muhammad]]'s political authority, who, according to Sunnis, were ideally [[Election|elected]] by the people or their representatives.<ref>''Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World'' (2004), vol. 1, p. 116-123.</ref> |

|||

Much debate occurs on the subject of which Islamic traditions are fixed principles, and which are subject to democratic change, or other forms of modification in view of changing circumstances. Some Muslims allude to an "Islamic" style of democracy which would recognize such distinctions. <ref> http://www.muslimnews.co.uk/news/news.php?article=11311 </ref>. Another sensitive issue involves the status of monarchs and other leaders, the degree of loyalty which Muslims owe such people, and what to do in case of a conflicting loyalties (e.g., if a monarch disagrees with an imam). |

Much debate occurs on the subject of which Islamic traditions are fixed principles, and which are subject to democratic change, or other forms of modification in view of changing circumstances. Some Muslims allude to an "Islamic" style of democracy which would recognize such distinctions. <ref> http://www.muslimnews.co.uk/news/news.php?article=11311 </ref>. Another sensitive issue involves the status of monarchs and other leaders, the degree of loyalty which Muslims owe such people, and what to do in case of a conflicting loyalties (e.g., if a monarch disagrees with an imam). |

||

Revision as of 11:59, 28 November 2007

Known as Islamic democracy, two kinds of democratic states can be recognized in the Islamic countries. The basis of this distinction has to do with how comprehensively Islam is incorporated into the affairs of the state. [1]

- A democratic state which recognizes Islam as state religion, such as Iran, Algeria or Bangladesh. Some religious values are incorporated into public life, but Islam is not the only source of law.

- A democratic state which endeavours to institute Sharia. It is also called as Islamist democracy. [2] Islamist democracy offers more comprehensive inclusion of Islam into the affairs of the state. Islamist democracy is a highly controversial topic.

According to Feldman the mainstream Islamists are not calling for Islamist, but Islamic, democracy.

On democracies with religious law, see Religious democracy.

The compatibility of Islam and democracy

Most Islamic democracies fall under the first definition, leading many analysts to dismiss the compatibility of Islam with democracy. The arguments for this position include: Islam and secularism are opposite forces; theocracy is incompatible with democracy; and Muslim culture lacks the liberal social attitudes of democratic societies.

Sunni viewpoint

Sunnis believe that after the Prophet Muhammad, no one has direct access to God’s will, and therefore no one person or group has the legitimacy or authority to claim a pope- or priesthood-like status in the Muslim community. Therefore the democratic ideal of a “government by the people” is compatible with the notion of an Islamic democracy. Muslims often refer to the system by which the first four ("Rightly Guided") caliphs were chosen, using a traditional Arab mechanism of consultation. While these deliberations were not democratic in the modern sense (rather, decision-making power lay with a council of notables or clan patriarchs), they show that some appeals to popular consent are permissible (though not necessarily required) within Islam.[3] (See also: Shura).

In the early Islamic Caliphate, the head of state, the Caliph, had a position based on the notion of a successor to Muhammad's political authority, who, according to Sunnis, were ideally elected by the people or their representatives.[4]

Much debate occurs on the subject of which Islamic traditions are fixed principles, and which are subject to democratic change, or other forms of modification in view of changing circumstances. Some Muslims allude to an "Islamic" style of democracy which would recognize such distinctions. [5]. Another sensitive issue involves the status of monarchs and other leaders, the degree of loyalty which Muslims owe such people, and what to do in case of a conflicting loyalties (e.g., if a monarch disagrees with an imam).

Shi'i viewpoint

According to the Shi'i understanding, the Prophet Muhammad named as his successor (as leader, not as prophet--Muhammad being the final prophet), his son-in-law 'Ali. Therefore the first three of the four "Rightly Guided" Caliphs recognized by Sunnis ('Ali being the fourth), are considered usurpers, notwithstanding their having been "elected" through some sort of consilar deliberation. The largest Shi'a grouping--the Ithna Ashariya sect which rules Iran--recognizes a series of twelve imams, the last of which (the Hidden Imam) is still alive and the Shi'a are waiting for his reappearance. The second-largest Shi'i sect, the Ismailis, recognize a series of seven imams.

Since the revolution in Iran, Twelver Shi'i political thought has been dominated by the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Imam Khomeini argued that in the absence of the Hidden Imam and other divinely-appointed figures (in whom ultimate political authority rests), Muslims have not only the right, but also the obligation, to establish an "Islamic state." To that end they must turn to scholars of Islamic law (fiqh) who are qualified to interpret the Qur'an and the writings of the imams. Khomeini distinguishes between Conventional Fiqh and Dynamic Fiqh, which he believes to also be necessary.

Khomeini divides the Islamic commandments or Ahkam into three branches:

- the primary commandments (Persian: حكم اوليه)

- the secondary commandments (Persian: حكم ثانويه) and

- the state commandments (Persian: حكم حكومتي).

This last includes all commandments which relate to public affairs, such as constitutions, social security, insurance, bank, labour law, taxation, elections, congress etc. Some of these codes may not strictly or implicitly pointed out in the Quran and generally in the Sunnah.

Khomeini emphasized that the Islamic state has absolute right (Persian: ولايت مطلقه) to enact state commandments, even if it violates the primary or secondary commandments of Islam. For example an Islamic state can ratify (according to some constitution) mandatory insurance of employees to all employers being Muslim or not even if it violates mutual consent between them. This shows the compatibility of Islam with modern forms of social codes for present and future life [6], as various countries and nations may have different kinds of constitutions now and will may have new ones in future. [7]

Criticism

"Today, two groups prevent the genuine reform movement seeking religious democracy: One group consists of those who think the less freedom a society enjoys, the stronger religion will be. They oppose the democratic process. The second is the group including those who believe that religion should be put aside from the scene of life in order to establish democracy and freedom." [8]

Two major arguments against the possibility of a democratic Islamic state are as follow:

- The Secularist argument is that democracy requires that the people be sovereign and that religion and state be separated. Without this separation there can be no freedom from tyranny.

- The Legalist argument is that, democracy may be accepted in a Christian, Buddhist, Hindu, etc. society but it can never enjoy a general acceptance in an Islamic society, because non-Muslim societies do not have Sharia, the comprehensive system of life to which its adherents should be committed. In this view anything outside of the rigid, but pervasive, interpretation of the Sharia is rejected and the absolute sovereignty of God prevails such that there is no role for the sovereignty of people. Mohammed Omar and his followers never made any claims that the Islamic State of Afghanistan was any sort of democracy.

Islamic democratic systems have the same human rights issues as other democracies, but some matters which may cause friction include appeasing anti-democratic Islamists, non-Muslim religious minorities, the role of Islam in state education (especially with regard to Sunni and Shia traditions), women's rights (See: Islamic feminist movement). This is further complicated by the deriving of punishments from Fiqh, or Islamic jurisprudence, where, as in other legal systems, precedent assists the judiciary to come to a decision. Since the judiciary is not independent of a system of religious codes that are essentially the collective reasoning of often highly conservative scholars, the system is inherently conservative, and thus is less flexible and able to adapt to developing views of the subjects listed above.

In addition, while some Islamic democracies ban alcohol outright, as it is against the religion, other governments allow the individual to choose whether to transgress Islam themselves. In these instances, while the act will be considered wrong by strict Muslims, the penalty is seen to be a spiritual not a worldly one.

Islamic democracy in practice

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2007) |

Legal scholar L. Ali Khan, however, argues that Islam is fully compatible with democracy. In his book, A Theory of Universal Democracy, Khan provides a critique of liberal democracy and secularism. He presents the concept of "fusion state" in which religion and state are fused. There are no contradictions in God's Universe, says Khan. Contradictions represent the limited knowledge that human beings have. According to the Quran and the Suuna, Muslims are fully capable of preserving spirituality and self-rule. [9]

Furthermore, counter arguments to these points assert that this attitude presuppose democracy as a static system which only embraces a particular type of social and cultural system, namely that of the post-Christian West. See: constitutional theocracy.

Muslim democrats, including Ahmad Moussalli (professor of Political science at the American University of Beirut), argue that concepts in the Qur'an point towards some form of democracy, or at least away from despotism. These concepts include shura (consultation), ijma' (consensus), al-hurriyya (freedom), al-huqquq al-shar'iyya (legitimate rights). For example shura (Aal `Imran 3:159, Ash-Shura 42:38) may include electing leaders to represent and govern on the community’s behalf. Government by the people is not therefore necessarily incompatible with the rule of Islam, whilst it has also been argued that rule by a religious authority is not the same as rule by a representative of Allah. This viewpoint, however, is disputed by more traditional Muslims. Prof Moussalli argues that despotic Islamic governments have abused the Qur'anic concepts for their own ends: "For instance, shura, a doctrine that demands the participation of society in running the affairs of its government, became in reality a doctrine that was manipulated by political and religious elites to secure their economic, social and political interests at the expense of other segments of society," (In Progressive Muslims 2003).

A further argument against Islamic democracy in practice, is that some democratic governments in Islamic states are not homegrown, but imposed by the West, such as the one in Afghanistan and the nascent post-Baathist regime in Iraq. [10]

Pakistan

Pakistan started off as the first category but has moved increasingly with the 1973 constitution to the second category, though frequent military coups have halted its democratic evolution.

Ausuf Ali, a former professor of business at the University of Karachi, argues that in the case of Pakistan (where democratically elected governments have been regularly overthrown by the military) shows that: "Islam and the Sharia, or Islamic law, simply do not have the conceptual resources, flexibility, and dynamism to suffice for the governance of a modern state and operation of a rational economy and an expanding civil society." In that case Ali is was arguing that "Pakistani styled extremist Islam and democracy are not compatible". [11]

Middle East

See also: Democracy in the Middle East

Waltz writes that transformations to democracy seemed on the whole to pass the Islamic Middle East by at a time when such transformations were a central theme in other parts of the world, although she does note that, of late, the increasing number of elections being held in the region indicates some form of adoption of democratic traditions.[12] There are several ideas on the relationship between Islam in the Middle East and democracy. Writing on The Guardian website [1], Brian Whitaker, the paper's Middle East editor, argued that there were four major obstacles to democracy in the region: the Imperial legacy, oil wealth, the Arab-Israeli conflict and militant or "backward-looking" Islam.

The imperial legacy includes the borders of the modern states themselves and the existence of significant minorities within the states. Acknowledgement of these differences is frequently suppressed usually in the cause of "national unity" and sometimes to obscure the fact that minority elite is controlling the country. Brian Whitaker argues that this leads to the formation of political parties on ethnic, religious or regional divisions, rather than over policy differences. Voting therefore becomes an assertion of one's identity rather than a real choice.

The problem with oil and the wealth it generates is that the states' rulers have the wealth to remain in power, as they can pay off or repress most potential opponents. Brian Whitaker argues that as there is no need for taxation there is less pressure for representation. Furthermore, Western governments require a stable source of oil and are therefore more prone to maintain the status quo, rather than push for reforms which may lead to periods of instability (Also see: Saudi America on Khilafah.com). This can be linked into political economy explanations for the occurrence of authoritarian regimes and lack of democracy in the Middle East, particularly the prevalence of rentier states in the Middle East.[13] A consequence of the lack of taxation that Whitaker talks of in such rentier economies is an inactive civil society. As civil society is seen to be an integral part of democracy it raises doubts over the feasibility of democracy developing in the Middle East in such situations.[14]

Whitaker's third point is that the Arab-Israeli conflict serves as a unifying factor for the countries of the Arab League, and also serves as an excuse for repression by Middle Eastern governments. For example, in March 2004 Sheikh Mohammed Fadlallah, Lebanon's leading Shia cleric, is reported as saying "We have emergency laws, we have control by the security agencies, we have stagnation of opposition parties, we have the appropriation of political rights - all this in the name of the Arab-Israeli conflict". The West, especially the USA, is also seen as a supporter of Israel, and so it and its institutions, including democracy, are seen by many Muslims as suspect. Khaled abu el-Fadl, a lecturer in Islamic law at the University of California comments "modernity, despite its much scientific advancement, reached Muslims packaged in the ugliness of disempowerment and alienation."

This repression by Arab rulers has led to the growth of radical Islamic movements, as they believe that the institution of an Islamic theocracy will lead to a more just society. However, these groups tend to be very intolerant of alternative views, including the ideas of democracy. Many Muslims who argue that Islam and democracy are compatible live in the West, and are therefore seen as "contaminated" by non-Islamic ideas. [2]

Orientalist scholars offer another viewpoint on the relationship between Islam and democratisation in the Middle East. They argue that the compatibility is simply not there between secular democracy and Arab-Islamic culture in the Middle East which has a strong history of undemocratic beliefs and authoritarian power structures.[15] Kedourie, a well known Orientalist scholar, said for example: “to hold simultaneously ideas which are not easily reconcilable argues, then, a deep confusion in the Arab public mind, at least about the meaning of democracy. The confusion is, however, understandable since the idea of democracy is quite alien to the mind-set of Islam.”[16] A view similar to this that understands Islam and democracy to be incompatible because of seemingly irreconcilable differences between Shar’ia and democratic ideals is also held by some Islamists. However within Islam there are ideas held by some that believe Islam and democracy in some form are indeed compatible due to the existence of the concept of Shura (meaning consultation) in the Qur’an. Views such as this have been expressed by various thinkers and political activists in the Middle East.[17]

Iran

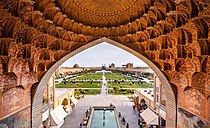

| Part of a series on |

| Islam in Iran |

|---|

|

| History of Islam in Iran |

| Scholars |

| Sects |

| Culture |

| Architecture |

| Organizations |

|

|

Theory

The idea and concept of Islamic democracy has been accepted by many Iranian scholars and intellectuals [18] [19] [20]. [21] [22]

There are also other Iranian scholars who oppose the concept of Islamic democracy and believe no major role for the people in the Islamic state. Among the most popular of them are Ayatollah Makarim al-Shirazi who have wrote: "If not referring to the people votes would result in accusations of tyranny then it is allowed to accept people vote as a secondary commandment" [23] Also Mohammad Taghi Mesbah Yazdi has more or less the same viewpoint.

On the other hand, clergies like Hassan Yousefi Eshkevari believe that: The obligatory religious commandments in public domain not necessarily imply recognition of religious state. These obligations can be interpreted as the power of Muslims' religious conscience and applying that through civil society [24]. These clergies strictly reject the concept of Islamic state regardless of being democratic or not. They also believe no relationship between Islam and democracy at all, opposing the interpretation of clergies like Ayatollah Makarim al-Shirazi from Islamic state. But they do not mention how legal laws as an example can not be implemented using civil societies and how to administer a country relying on conscience only.

Practice

Some Iranians, including Mohammad Khatami, categorize the Islamic republic of Iran as a kind of religious democracy. [25]

Other maintain that not only is the Islamic Republic of Iran undemocratic [3] but that Khomeini himself opposed the principle of democracy in his book Hokumat-e Islami: Wilayat al-Faqih, where he denied the need for any legislative body saying, "no one has the right to legislate ... except ... the Divine Legislator", [4] and during the Islamic Revolution, when he told Iranians, "Do not use this term, `democratic.` That is the Western style." [26] (Although it is in contrast with his commandment to Bazargan.[5]) It is a subject of lively debate among pro-Islamic Iranian intelligentsia. Also they maintain that Iran's sharia courts, the Islamic Revolutionary Court, blasphemy laws of the Islamic Republic of Iran, and the religious police violate the principles of democratic governance. [27]

The former Soviet Union

Many of the states of the former Soviet Union, including Russia have significant Muslim populations. They are mainly concentrated in the south of the region, to the east of the Black Sea. The democratic status of many of these states, such as Uzbekistan and others in Central Asia, is very controversial, and the Soviet Union itself was also officially an atheist state (although it made some concessions in Central Asia after the Basmachi rebellion). The resurgence of Islam, the break up of the Soviet Union and the attempts to introduce democracy all occurred within the same few years, and represented a huge, and not always peaceful, upheaval.

Russia's wars in majority Muslim Chechnya and Afghanistan have also strained relations in both Russia, and the other former Soviet states where there are significant Russian minorities. In some of the states, democracy has been seen as a western import, and has fallen to the same post-Soviet backlash as Communism has.

See also

- Religious democracy

- Institute on Religion and Democracy

- Dialogue Among Civilizations

- Clash of Civilizations

- Freedom deficit

References

- ^ http://hir.harvard.edu/articles/1128/

- ^ http://hir.harvard.edu/articles/1128/

- ^ Sohaib N. Sultan, Forming an Islamic Democracy

- ^ Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World (2004), vol. 1, p. 116-123.

- ^ http://www.muslimnews.co.uk/news/news.php?article=11311

- ^ http://www.gazellebookservices.co.uk/ISBN/1904063187.htm

- ^ http://www.nezam.org/english/wilayah_jawadi.htm

- ^ http://www.wwrn.org/article.php?idd=6426&sec=59&con=33

- ^ http://www.law.wisc.edu/students/wilj/abstracts/161.htm See abstract

- ^ http://www.khilafah.com/home/category.php?DocumentID=11722&TagID=2

- ^ http://www.beliefnet.com/story/25/story_2550_1.html Beliefnet

- ^ Waltz, S.E., 1995, Human Rights & Reform: Changing the Face of North African Politics, London, University of California Press Ltd

- ^ Beblawi, H., 1990, The Rentier State in the Arab World, in Luciani, G., The Arab State, London, Routledge

- ^ Weiffen, B., 2004, The Cultural-Economic Syndrome: Impediments to Democracy in the Middle East, www.dur.ac.uk/john.ashworth/EPCS/Papers/Weiffen.pdf

- ^ Weiffen, B., 2004, The Cultural-Economic Syndrome: Impediments to Democracy in the Middle East, www.dur.ac.uk/john.ashworth/EPCS/Papers/Weiffen.pdf

- ^ Kedourie, E., 1994, Democracy and Arab Political Culture, London, Frank Cass & Co Ltd, page 1

- ^ Esposito, J. & Voll, J.,2001, Islam and Democracy, Humanities, Volume 22, Issue 6

- ^ http://www.khatami.ir/

- ^ http://www.wwrn.org/article.php?idd=6426&sec=59&con=33

- ^ http://www.drsoroush.com

- ^ http://www.leader.ir/langs/EN/index.php?p=news&id=3447

- ^ http://www.khamenei.ir/EN/News/detail.jsp?id=20031220A

- ^ انوار الفقاهه- كتاب البيع - ج 1 ص 516

- ^ http://www.ibtauris.com/ibtauris/display.asp?ISB=1845111346&TAG=&CID=

- ^ http://www2.irna.com/en/news/view/line-17/0702089736162511.htm

- ^ Bakhash, Shaul, The Reign of the Ayatollahs, p.73

- ^ http://www.memritv.org/Transcript.asp?P1=401 Khatami Clashes with Reformist Students at Tehran University

Bibliography

- Mahmoud Sadri and Ahmad Sadri (eds.) 2002 Reason, Freedom, and Democracy in Islam: Essential Writings of Abdolkarim Soroush, Oxford University Press

- Omid Safi (ed.) 2003 Progressive Muslims: On Justice, Gender and Pluralism, Oneworld

- Azzam S. Tamimi 2001 Rachid Ghannouchi: A Democrat within Islamism, Oxford University Press

- Khan L. Ali 2003 A Theory of Universal Democracy, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers

External links

- Islam and Democracy: Perceptions and Misperceptions by Dr. Mohammad Omar Farooq

- Democracy and the Muslim World ( series of articles on Islam and Democracy from Islamica Magazine)

- Islamic Democracies (article)

- Preview of the Seoul Conference on The Community of Democracies: Challenges and Threats to Democracy

- Marina Ottoway, et al., "Democratic Mirage in the Middle East," Carnegie Endowment for Ethics and International Peace, Policy Brief 20, (October 20, 2002). Internet, available online at: http://www.ceip.org/files/publications/HTMLBriefs-WP/20_October_2002_Policy_Brief/20009536v01.html

- Marina Ottoway and Thomas Carothers, "Think Again: Middle East Democracy,"Foreign Policy (Nov./Dec. 2004). Internet, available online at: http://www.foreignpolicy.com/story/cms.php?story_id=2705&print=1

- Chris Zambelis, "The Strategic Implications of Political Liberalization and Democratization in the Middle East," Parameters, (Autumn 2005). Internet, available online at: http://www.carlisle.army.mil/usawc/Parameters/05autumn/zambelis.htm

- The Muslim's world future is freedom Book review, with some controversial content.

- National Union for Democracy in Iran

- Democracy in the Middle East A series of articles in the Guardian on the problems of democracy in the region by Brian Whitaker.

- Expect the Unexpected: A Religious Democracy in Iran

- Iranian President Mohammad Khatami Vows to Establish Religious Democracy in Iran

- Recent Elections and the Future of Religious Democracy in Iran

- Minimal Islam Is the Answer for Iran

- Democracy Lacking in Muslim World

- Islamic Revolutionary Guard Official in Tehran University Lecture (Part I): Islam Has Nothing in Common with Democracy