A Beautiful Mind (film): Difference between revisions

→External links: cats |

Mfmoviefan (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 96: | Line 96: | ||

==Release== |

==Release== |

||

''A Beautiful Mind'' received a limited release on December 21, 2001, receiving positive reviews. It was later released in America on January 4, 2002. [[Rotten Tomatoes]] showed a 78% approval rating among critics with a movie consensus stating "The well-acted ''A Beautiful Mind'' is both a moving love story and a revealing look at mental illness."<ref name="RT">{{cite web | work=Rotten Tomatoes | title =A Beautiful Mind | url=http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/beautiful_mind/| accessdate=2007-08-14}}</ref> [[Roger Ebert]] gave the film four stars (his highest rating) in his Chicago Sun-Times review and, along with co-host [[Richard Roeper]] on the television show ''[[At the Movies with Ebert & Roeper|Ebert & Roeper]]'', gave the film a "thumbs up" rating. Roeper also stated "this is one of the very best films of the year".<ref>{{cite web | work=Ebert & Roeper | title=A Beautiful Mind|url=http://bventertainment.go.com/tv/buenavista/ebertandroeper/index2.html?sec=6&subsec=A+Beautiful+Mind| accessdate=2007-08-15}}</ref> Mike Clark of USA Today gave three and a half out of four stars and also praised Crowe's performance and referred to as a welcomed follow up to Howard's previous film ''[[The Grinch (film)|The Grinch]]'';<ref>{{cite news | work=USA Today |author=Clark, Mike | title=Crowe brings to 'Mind' a great performance|url=http://www.usatoday.com/life/movies/2001-12-21-beautiful-mind-review.htm| accessdate=2007-08-27 | date=2001-12-20}}</ref> however, Desson Thomson of the [[Washington Post]] found the film to be "one of those formulaically rendered Important Subject movies",<ref name="RT"/> and Charles Taylor of [[Salon Magazine]] gave the film a scathing review, calling Crowe's performance "the biggest load of hooey to stink up the screen this year".<ref>{{cite web | work=Salon Magazine |date=2001-12-21 | title=A Beautiful Mind|url=http://archive.salon.com/ent/movies/review/2001/12/21/beautiful_mind/index.html| accessdate=2007-08-27}}</ref> The mathematics in the film were well-praised by the mathematics community, including the real John Nash.<ref name="Swarthmore">{{cite web | work=Swarthmore College Bulletin |author=Dana Mackenzie | title=Beautiful Math|url=http://www.swarthmore.edu/bulletin/june02/bayer.html| accessdate=2007-09-01}}</ref> |

''A Beautiful Mind'' received a limited release on December 21, 2001, receiving positive reviews. It was later released in America on January 4, 2002. [[Rotten Tomatoes]] showed a 78% approval rating among critics with a movie consensus stating "The well-acted ''A Beautiful Mind'' is both a moving love story and a revealing look at mental illness."<ref name="RT">{{cite web | work=Rotten Tomatoes | title =A Beautiful Mind | url=http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/beautiful_mind/| accessdate=2007-08-14}}</ref> [[Roger Ebert]] gave the film four stars (his highest rating) in his Chicago Sun-Times review and, along with co-host [[Richard Roeper]] on the television show ''[[At the Movies with Ebert & Roeper|Ebert & Roeper]]'', gave the film a "thumbs up" rating. Roeper also stated "this is one of the very best films of the year".<ref>{{cite web | work=Ebert & Roeper | title=A Beautiful Mind|url=http://bventertainment.go.com/tv/buenavista/ebertandroeper/index2.html?sec=6&subsec=A+Beautiful+Mind| accessdate=2007-08-15}}</ref> ''[[Mark Sells]]'' of ''[[The Reel Deal]]'' gave the film 5 out of 5 stars, suggesting that the film should have a date with Oscar even though it "challenges us to decipher between what is real and what is artificial." <ref>{{cite web |last=Sells |first=Mark |work=The Reel Deal |title=A Beautiful Mind: Review |url=http://www.thereeldeal.co/reviews/abeautifulmind.html}}</ref> |

||

Mike Clark of USA Today gave three and a half out of four stars and also praised Crowe's performance and referred to as a welcomed follow up to Howard's previous film ''[[The Grinch (film)|The Grinch]]'';<ref>{{cite news | work=USA Today |author=Clark, Mike | title=Crowe brings to 'Mind' a great performance|url=http://www.usatoday.com/life/movies/2001-12-21-beautiful-mind-review.htm| accessdate=2007-08-27 | date=2001-12-20}}</ref> however, Desson Thomson of the [[Washington Post]] found the film to be "one of those formulaically rendered Important Subject movies",<ref name="RT"/> and Charles Taylor of [[Salon Magazine]] gave the film a scathing review, calling Crowe's performance "the biggest load of hooey to stink up the screen this year".<ref>{{cite web | work=Salon Magazine |date=2001-12-21 | title=A Beautiful Mind|url=http://archive.salon.com/ent/movies/review/2001/12/21/beautiful_mind/index.html| accessdate=2007-08-27}}</ref> The mathematics in the film were well-praised by the mathematics community, including the real John Nash.<ref name="Swarthmore">{{cite web | work=Swarthmore College Bulletin |author=Dana Mackenzie | title=Beautiful Math|url=http://www.swarthmore.edu/bulletin/june02/bayer.html| accessdate=2007-09-01}}</ref> |

|||

During the five-day weekend of the limited release, ''A Beautiful Mind'' opened at the twelfth spot at the [[box office]],<ref>{{cite web | work=[[Box Office Mojo]] | title=Weekend Box Office Results for December 21–25, 2001|url=http://www.boxofficemojo.com/weekend/chart/?view=&yr=2001&wknd=51b&p=.htm| accessdate=2008-05-22}}</ref> peaking at the number two spot following the wide release.<ref>{{cite web | work=[[Box Office Mojo]] | title=Weekend Box Office Results for January 4–6, 2002|url=http://www.boxofficemojo.com/weekend/chart/?yr=2002&wknd=001&p=.htm| accessdate=2008-05-22}}</ref> The film went to gross $170,742,341 in North America and $313,542,341 worldwide.<ref>{{cite web | work=[[Box Office Mojo]] | title=A Beautiful Mind (2001)|url=http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=beautifulmind.htm| accessdate=2010-11-08}}</ref> |

During the five-day weekend of the limited release, ''A Beautiful Mind'' opened at the twelfth spot at the [[box office]],<ref>{{cite web | work=[[Box Office Mojo]] | title=Weekend Box Office Results for December 21–25, 2001|url=http://www.boxofficemojo.com/weekend/chart/?view=&yr=2001&wknd=51b&p=.htm| accessdate=2008-05-22}}</ref> peaking at the number two spot following the wide release.<ref>{{cite web | work=[[Box Office Mojo]] | title=Weekend Box Office Results for January 4–6, 2002|url=http://www.boxofficemojo.com/weekend/chart/?yr=2002&wknd=001&p=.htm| accessdate=2008-05-22}}</ref> The film went to gross $170,742,341 in North America and $313,542,341 worldwide.<ref>{{cite web | work=[[Box Office Mojo]] | title=A Beautiful Mind (2001)|url=http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=beautifulmind.htm| accessdate=2010-11-08}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 14:38, 18 March 2011

| A Beautiful Mind | |

|---|---|

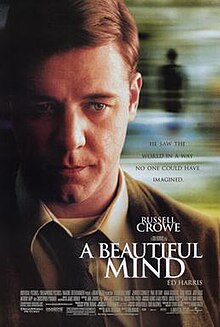

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ron Howard |

| Screenplay by | Akiva Goldsman |

| Produced by | Ron Howard Brian Grazer |

| Starring | Russell Crowe Jennifer Connelly Ed Harris Paul Bettany Christopher Plummer Josh Lucas Judd Hirsch |

| Cinematography | Roger Deakins |

| Edited by | Daniel P. Hanley Mike Hill |

| Music by | James Horner |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Studios (USA) DreamWorks (non-USA) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 135 minutes |

| Country | Template:Film US |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $60 million |

| Box office | $313,542,341 |

A Beautiful Mind is a 2001 American film based on the life of John Forbes Nash, Jr., a Nobel Laureate in Economics.[2] The film was directed by Ron Howard and written by Akiva Goldsman. It was inspired by a bestselling, Pulitzer Prize-nominated 1998 book of the same name by Sylvia Nasar. The film stars Russell Crowe, along with Jennifer Connelly, Ed Harris, Christopher Plummer and Paul Bettany.

The story begins in the early years of a young schizophrenic prodigy named John Nash. Early in the film, Nash begins developing paranoid schizophrenia and endures delusional episodes while painfully watching the loss and burden his condition brings on his wife and friends.

The film opened in US cinemas on December 21, 2001. It was well-received by critics, grossed over $170 million worldwide, and went on to win four Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Supporting Actress. It was also nominated for Best Leading Actor, Best Editing, Best Makeup, and Best Score. The film has been criticized for its inaccurate portrayal of some aspects of Nash's life. The film fictionally portrayed his hallucinations as visual and auditory, when in fact they were exclusively auditory. Also, Nasar concluded that Nash's refusal to take drugs "may have been fortunate," since their side effects "would have made his gentle re-entry into the world of mathematics a near impossibility"; in the screenplay, however, just before he receives the Nobel Prize, Nash speaks of taking "newer medications."[3]

Plot

In 1947, John Nash (Russell Crowe) arrives at Princeton University as a new graduate student. He is a recipient of the prestigious Carnegie Prize for mathematics; although he was promised a single room, his roommate Charles Herman (Paul Bettany), a literature student, greets him as he moves in and soon becomes his best friend. Nash also meets a group of other promising math and science graduate students, Martin Hansen (Josh Lucas), Richard Sol (Adam Goldberg), Ainsley (Jason Gray-Stanford), and Bender (Anthony Rapp), with whom he strikes up an awkward friendship. Nash admits to Charles that he is better with numbers than he is with people.

The mathematics department chairman of Princeton informs Nash, who has missed many of his classes, that he cannot begin work until he finishes a thesis paper, prompting him to seek a truly original idea for the paper. A woman at the bar is what ultimately inspires his fruitful work in the concept of governing dynamics, a theory in mathematical economics. After the conclusion of Nash's studies as a student at Princeton, he accepts a prestigious appointment at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), along with his friends Sol and Bender.

In 1953, while teaching a class on calculus at MIT, he places a particularly interesting problem on the chalkboard that he dares his students to solve. He is not particularly interested in teaching and his delusions even cause him to miss the class. When a Salvadoran student, Alicia Larde (Jennifer Connelly), comes to his office to discuss why he did not show up, she also asks him to dinner and the two fall in love and eventually marry.

On a return visit to Princeton, Nash runs into his former roommate Charles and meets Charles' young niece Marcee (Vivien Cardone), whom he adores. Nash is invited to a secret Department of Defense facility in the Pentagon to crack a complex encryption of an enemy telecommunication. Nash is able to decipher the code mentally, to the astonishment of other codebreakers. Here, he encounters the mysterious William Parcher (Ed Harris), who belongs to the United States Department of Defense. Parcher observes Nash's performance from above, while partially concealed behind a screen. Parcher gives Nash a new assignment to look for patterns in magazines and newspapers, ostensibly to thwart a Soviet plot. He must write a report of his findings and place them in a specified mailbox. After being chased by Soviet agents and an exchange of gunfire, Nash becomes increasingly paranoid and begins to behave erratically.

After observing this erratic behavior, Alicia informs a psychiatric hospital. Later, while delivering a guest lecture at Harvard University, Nash realizes that he is being watched by a hostile group of people, and although he attempts to flee, he is forcibly sedated and sent to a psychiatric facility. Nash's internment seemingly confirms his belief that the Soviets are trying to extract information from him. He views the officials of the psychiatric facility as Soviet kidnappers. At one point, he gorily tries to dig out of his arm an implant he received at an unused warehouse on the MIT campus, which was supposedly used as a listening facility by the DoD.

Alicia, desperate and obligated to help her husband, visits the mailbox and retrieves the never-opened "top secret" documents that Nash had delivered there. When confronted with this evidence, Nash is finally convinced that he has been hallucinating. The Department of Defense agent William Parcher and Nash's secret assignment to decode Soviet messages was in fact all a delusion. Even more surprisingly, Nash's "prodigal roommate" Charles and his niece Marcee are also products of his mind.

After a series of insulin shock therapy sessions, Nash is released on the condition that he agrees to take antipsychotic medication; however, the drugs create negative side-effects that affect his sexual and emotional relationship with his wife and, most dramatically, his intellectual capacity. Frustrated, Nash secretly stops taking his medication and hoards his pills, triggering a relapse of his psychosis.

In 1956, while bathing his infant son, Nash becomes distracted and wanders off. Alicia is hanging laundry in the backyard and observes that the back gate is open. She discovers that Nash has turned an abandoned shed in a nearby grove of trees into an office for his work for Parcher. Upon realizing what has happened, Alicia runs into the house to confront Nash and barely saves their child from drowning in the bathtub. When she confronts him, Nash claims that his friend Charles was watching their son. Alicia runs to the phone to call the psychiatric hospital for emergency assistance. Nash suddenly sees Parcher who urges him to kill his wife, but Nash angrily refuses to do such a thing. After Parcher points a gun at her, Nash lunges for him, accidentally knocking Alicia and the baby to the ground. Alicia flees the house in fear with their child, but Nash steps in front of her car to prevent her from leaving. After a moment, he tells Alicia, "She never gets old"--referring to Marcee, who, although years have passed since their first encounter, has remained exactly the same age and is still a little girl. Realizing the implications of this fact, he finally accepts that although all three people seem completely real, they are in fact part of his hallucinations.

Caught between the intellectual paralysis of the antipsychotic drugs and his delusions, Nash and Alicia decide to try to live with his abnormal condition. Nash consciously says goodbye to the three delusional characters forever in his attempts to ignore his hallucinations and not feed "his demons". He thanks Charles for being his best friend over the years, and says a tearful goodbye to Marcee, stroking her hair and calling her "baby girl", telling them both he would not speak to them anymore. They still continue to haunt him, with Charles mocking him for cutting off their friendship, but Nash learns to ignore them.

Nash grows older and approaches his old friend and intellectual rival, Martin Hansen, now head of the Princeton mathematics department, who grants him permission to work out of the library and audit classes. Even though Nash still suffers from hallucinations and mentions taking newer medications, he is ultimately able to live with and largely ignore his psychotic episodes. He takes his situation in stride and humorously checks to ensure that any new acquaintances are in fact real people, not hallucinations.

Nash eventually earns the privilege of teaching again. In 1994, Nash is honored by his fellow professors for his achievement in mathematics, and goes on to win the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics for his revolutionary work on game theory. Nash and Alicia are about to leave the auditorium in Stockholm, when Nash sees Charles, Marcee and Parcher standing and watching him with blank expressions on their faces. Alicia asks Nash, "What is it?" Nash replies, "Nothing. Nothing at all." With that, they both leave the auditorium.

Cast

- Russell Crowe as John Forbes Nash, Jr., A mathematical genius who is obsessed with finding an original idea to ensure his legacy. There was difficulty when casting Crowe, who was well-liked by the producers, when he went to film Gladiator in a different time-zone and was difficult to reach for an extended period of time to attach him to the project.[4]

- Jennifer Connelly as Alicia Nash, a later student of Nash who catches his interest. Connelly was cast after Ron Howard drew comparisons to her and Alicia Nash, both academically and in facial features.[4]

- Paul Bettany as Charles Herman, Nash's cheerful, supportive roommate and best friend throughout graduate school. The character of Charles was not written to be English; however, director Brian Helgeland provided a tape of Bettany from A Knight's Tale. The filmmakers agreed that the character could be British, based on Bettany's performance in the film.[5]

- Ed Harris as William Parcher, a highly dedicated and forceful government agent for the Department of Defense. He recruits Nash to help fight Soviet spies.

- Josh Lucas as Martin Hansen, Nash's friendly rival from his graduate school years at Princeton. In the end, Hansen tells Nash that nobody wins, and they are at that point to consider each other as equals.

- Adam Goldberg as Sol, a friend of Nash's from Princeton University who is chosen, along with Bender, to work with him at MIT.

- Anthony Rapp as Bender, a friend of Nash's from Princeton University who is chosen, along with Sol, to work with him at MIT.

- Vivien Cardone as Marcee, Charles' young niece.

- Christopher Plummer as Dr. Rosen, Nash's doctor at a psychiatric hospital.

- Judd Hirsch as Helinger, the head of the Princeton mathematics department.

- Jason Gray-Stanford as Ainsley Neilson, the symbol cryptography professor. Nash pays particular attention to his tie.

Production

Producer Brian Grazer first read an excerpt of Sylvia Nasar's book A Beautiful Mind in Vanity Fair. Grazer immediately purchased the rights to the film. He eventually brought the project to Ron Howard, who had scheduling conflicts and was forced to pass. Grazer later said that many A-list directors were calling with their point of view on the project. He eventually focused on a particular director, who coincidentally was only available at the same time Howard was available. Grazer was forced to make a decision and chose Howard.[6]

Grazer then met with a number of screenwriters, mostly consisting of "serious dramatists", but he chose Akiva Goldsman instead, because of his strong passion and desire for the project. Goldsman's creative take on the project was to not allow the viewers to understand that they are viewing an alternate reality until a specific point in the film. This was done to rob the viewers of their feelings in the same way that Nash himself was. Howard agreed to direct the film based only on the first draft. He then requested that Goldsman accentuate the love story aspect.[7]

Dave Bayer, a professor of Mathematics at Barnard College, Columbia University,[8] was consulted on the mathematical equations that appear in the film. Bayer later stated that he approached his consulting role as an actor when preparing equations, such as when Nash is forced to teach a calculus class, and arbitrarily places a complicated problem on the blackboard. Bayer focused on a character who did not want to teach ordinary details and was more concerned with what was interesting. Bayer received a cameo role in the film as a professor that lays his pen down for Nash in the pen ceremony near the end of the film.[9]

Greg Cannom was chosen to create the makeup effects for A Beautiful Mind, specifically the age progression of the characters. Russell Crowe had previously worked with Cannom on The Insider. Howard had also worked with Cannom on Cocoon. Each character's stages of makeup were broken down by the number of years that would pass between levels. Cannom stressed subtlety between the stages, but worked toward the ultimate stage of "Older Nash". It was originally decided that the makeup department would merely age Russell Crowe throughout the film; however, at Crowe's request, the makeup purposefully pulled Crowe's look towards the facial features of the real John Nash. Cannom developed a new silicone-type makeup that could simulate real skin and be used for overlapping applications, shortening the application time from eight hours to four hours. Crowe was also fitted with a number of dentures to give him a slight overbite throughout the film.[10]

Howard and Grazer chose frequent collaborator James Horner to score the film because of familiarity and his ability to communicate. Howard said, regarding Horner, "It's like having a conversation with a writer or an actor or another director." A running discussion between the director and the composer was the concept of high-level mathematics being less about numbers and solutions, and more akin to a kaleidoscope, in that the ideas evolve and change. After the first screening of the film, Horner told Howard: "I see changes occurring like fast-moving weather systems." He chose it as another theme to connect to Nash's ever-changing character. Horner chose Welsh singer Charlotte Church to sing the soprano vocals after deciding that he needed a balance between a child and adult singing voice. He wanted a "purity, clarity and brightness of an instrument" but also a vibrato to maintain the humanity of the voice.[11]

The film was shot 90% chronologically. Three separate trips were made to the Princeton University campus. During filming, Howard decided that Nash's delusions should always first be introduced audibly and then visually. This not only provides a visual clue, but establishes the delusions from Nash's point of view. The real John Nash's delusions were also only auditory. A technique was also developed to visualize Nash's epiphanies. After speaking to a number of mathematicians who described it as "the smoke clearing", "flashes of light" and "everything coming together", the filmmakers decided upon a flash of light appearing over an object or person to signify Nash's creativity at work.[5] Two night shots were done at Fairleigh Dickinson University's campus in Florham Park, NJ, in the Vanderbilt Mansion ballroom.[12]

Many actors were considered for the role of John Nash, including Bruce Willis, Kevin Costner, John Travolta, Tom Cruise, John Cusack, Charlie Sheen, Robert Downey Jr., Nicolas Cage, Johnny Depp, Ralph Fiennes, Jared Leto, Brad Pitt, Alec Baldwin, Mel Gibson, Sean Penn, Guy Pearce, Matthew Broderick, Gary Oldman and Keanu Reeves. Cruise was lobbying for the part until Ron Howard ultimately cast Russell Crowe after he saw his performance in Gladiator.

The producers had not originally thought of Jennifer Connelly for the role of Alicia. She was starring in Requiem for a Dream with Jared Leto. When Leto went to screen test for John, Connelly read opposite him as Alicia. The producers fell in love with the idea of Connelly as Alicia but didn't cast Leto.

Portia de Rossi, Catherine McCormack, Meg Ryan, Rachel Griffiths and Amanda Peet were among the many actresses who lobbied for the role of Alicia. However, Ryan dropped out before production began.

Divergence from actual events

The narrative of the film differs considerably from the actual events of Nash's life. The film has been criticized for this, but the filmmakers had consistently said that the film was not meant to be a literal representation.[13] One difficulty was in portraying stress and mental illness within one person's mind.[14] Sylvia Nasar stated that the filmmakers "invented a narrative that, while far from a literal telling, is true to the spirit of Nash's story".[15] The film made his hallucinations visual and auditory when, in fact, they were exclusively auditory. Furthermore, while in real life Nash spent his years between Princeton and MIT as a consultant for the RAND Corporation in California, in the film he is portrayed to have worked for the Pentagon instead. It is true that his handlers, both from faculty and administration, had to introduce him to assistants and strangers.[5][16] The PBS documentary A Brilliant Madness attempts to portray his life more accurately.[17]

The differences were substantial. Few if any of the characters in the film, besides John and Alicia Nash, corresponded directly to actual people.[18] The discussion of the Nash equilibrium was criticized as over-simplified. In the film, schizophrenic hallucinations appeared while he was in graduate school, when in fact they did not show up until some years later. No mention is made of Nash's supposed homosexual experiences at RAND,[15][19] which Nash and his wife both denied.[20] Nash also fathered a son, John David Stier (born June 19, 1953), by Eleanor Agnes Stier (1921–2005), a nurse whom he abandoned when informed of her pregnancy.[21]

The movie also did not include Alicia's divorce of John in 1963. It was not until Nash won the Nobel Memorial Prize that they renewed their relationship, although she allowed him to live with her as a boarder beginning in 1970. They remarried in 2001.[19]

During graduate school, it appears in the movie that Nash was averse to game playing, when, in fact, according to Nasar's biography, he spent many hours playing games and even created a new game called "John" or "Nash" (Hex). Interestingly, the game was somewhat similar to Go, but the shape of the squares became hexagons. The game, somewhat in conflict with the movie's mathematical point, was not one in which "nobody wins," but was "a zero-sum two-person game with perfect information in which one player always has a winning strategy" (p. 77). Though this game was not shown in the film's theatrical cut, a deleted scene shows Nash inventing the game and showing it off to his friends at Princeton.

Nash is shown to join Wheeler Laboratory at MIT, but there is no such lab. He was appointed as C.L.E. Moore Instructor at MIT.[22] The pen ceremony tradition at Princeton shown in the film is completely fictitious.[5][23] In 1947, the theory of a triple helix had not been proposed yet, yet Ainsley's tie appears to have triple helices on it; Triple-stranded DNA was hypothesized during the 1950s but was not formally proposed until 1952 by Linus Pauling in Nature. The film has Nash saying around the time of his Nobel prize in 1994: "I take the newer medications", when in fact Nash did not take any medication from 1970 onwards, something Nash's biography highlights. Howard later stated that they added the line of dialogue because it was felt as though the film was encouraging the notion that all schizophrenics can overcome their illness without medication.[5] Nash also never gave an acceptance speech for his Nobel prize because of fears the organisers had regarding his mental instability.[23] Around the time of the Oscar nominations, Nash was accused of being anti-semitic. Nash denied this and it was speculated that the accusation was designed to affect the votes inside the Academy Awards.[20]

Release

A Beautiful Mind received a limited release on December 21, 2001, receiving positive reviews. It was later released in America on January 4, 2002. Rotten Tomatoes showed a 78% approval rating among critics with a movie consensus stating "The well-acted A Beautiful Mind is both a moving love story and a revealing look at mental illness."[24] Roger Ebert gave the film four stars (his highest rating) in his Chicago Sun-Times review and, along with co-host Richard Roeper on the television show Ebert & Roeper, gave the film a "thumbs up" rating. Roeper also stated "this is one of the very best films of the year".[25] Mark Sells of The Reel Deal gave the film 5 out of 5 stars, suggesting that the film should have a date with Oscar even though it "challenges us to decipher between what is real and what is artificial." [26] Mike Clark of USA Today gave three and a half out of four stars and also praised Crowe's performance and referred to as a welcomed follow up to Howard's previous film The Grinch;[27] however, Desson Thomson of the Washington Post found the film to be "one of those formulaically rendered Important Subject movies",[24] and Charles Taylor of Salon Magazine gave the film a scathing review, calling Crowe's performance "the biggest load of hooey to stink up the screen this year".[28] The mathematics in the film were well-praised by the mathematics community, including the real John Nash.[9]

During the five-day weekend of the limited release, A Beautiful Mind opened at the twelfth spot at the box office,[29] peaking at the number two spot following the wide release.[30] The film went to gross $170,742,341 in North America and $313,542,341 worldwide.[31]

Awards

In 2002, the film was awarded four Academy Awards for Adapted Screenplay (Akiva Goldsman), Best Picture (Brian Grazer and Ron Howard), Directing (Ron Howard), and Supporting Actress (Jennifer Connelly). It also received four other nominations for Best Actor in a Leading Role (Russell Crowe), Film Editing (Mike Hill and Daniel P. Hanley), Best Makeup (Greg Cannom and Colleen Callaghan), and Original Music Score (James Horner).[32] The 2002 BAFTAs awarded the film Best Actor and Best Actress to Russell Crowe and Jennifer Connelly, respectively. It also nominated the film for Best Film, Best Screenplay, and the David Lean Award for Direction.[33] At the 2002 AFI Awards, Jennifer Connelly won for Best Featured Female Actor.[34] In 2006, it was named #93 in AFI's 100 Years... 100 Cheers. The film was also nominated for Movie of the Year, Actor of the Year (Russell Crowe), and Screenwriter of the Year.[35]

Home media

A Beautiful Mind was released on VHS and DVD in the United States on June 25, 2002 as a two-disc set.[36] The first disc featured two separate audio commentaries from director Ron Howard and Akiva Goldsman, deleted scenes with optional commentary from the director, and production notes. The second disc included documentaries such as "Inside A Beautiful Mind" a making-of documentary, "A Beautiful Partnership: Ron Howard and Brian Grazer" detailing the partnership between the director and the producer, "Development of the Screenplay" discussing Akiva Goldsman scripting of the film, "The Process of Age Progression" detailing the makeup effects, "Casting Russell Crowe and Jennifer Connelly", "Creation of the Special Effects", "Scoring the Film", as well as "Meeting John Nash" displaying the real John Nash. Footage of the real John Nash accepting the Nobel Prize for Economics is also included along with reactions from the winners of the Academy Awards, storyboard comparisons, the theatrical trailer and an advertisement for the soundtrack to the film.

See also

- List of American films of 2001

- A Beautiful Mind: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack

- Mental illness in films

- Apophenia

- John Forbes Nash, Jr.

References

- ^ "A Beautiful Mind". Variety. Retrieved 2009-07-17.

- ^ http://www.princeton.edu/mudd/news/faq/topics/nash.shtml

- ^ USAToday.com

- ^ a b A Beautiful Mind DVD featurette Casting Russell Crowe and Jennifer Connelly, [2002]

- ^ a b c d e A Beautiful Mind DVD commentary featuring Ron Howard, [2002]

- ^ A Beautiful Mind DVD featurette A Beautiful Partnership: Ron Howard and Brian Grazer, [2002]

- ^ A Beautiful Mind DVD featurette Development of the Screenplay, [2002]

- ^ "DAVID ALLEN BAYER: Professor of Mathematics". Barnard College, Columbia University. 2008. Retrieved 2009-12-25.

- ^ a b Dana Mackenzie. "Beautiful Math". Swarthmore College Bulletin. Retrieved 2007-09-01. Cite error: The named reference "Swarthmore" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ A Beautiful Mind DVD featurette The Process of Age Progression, [2002]

- ^ A Beautiful Mind DVD featurette Scoring the Film, [2002]

- ^ "Fairleigh Dickinson University turned into a "different place"". CountingDown.com. 2001-04-30. Retrieved 2009-05-10.

- ^ About.com: Ron Howard Interview

- ^ "A Beautiful Mind". Mathematical Association of America. Retrieved 11 August 2007.

- ^ a b "A Real Number". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- ^ "A Brilliant Madness: Special Features". PBS. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- ^ "A Brilliant Madness". PBS. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- ^ Sylvia Nasar, A Beautiful Mind, Touchstone 1998

- ^ a b Nasar book

- ^ a b "Nash: Film No Whitewash". CBS News: 60 Minutes. 2002-03-14. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- ^ "Eleanor Stier, 84". The Boston Globe. 2005-04-10. Retrieved 5 December 2007.

- ^ "MIT facts meet fiction in 'A Beautiful Mind'". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- ^ a b "FAQ John Nash". Seeley G. Mudd Library at Princeton University. Retrieved 16 August 2007. Cite error: The named reference "inaccuracies" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b "A Beautiful Mind". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2007-08-14.

- ^ "A Beautiful Mind". Ebert & Roeper. Retrieved 2007-08-15.

- ^ Sells, Mark. "A Beautiful Mind: Review". The Reel Deal.

- ^ Clark, Mike (2001-12-20). "Crowe brings to 'Mind' a great performance". USA Today. Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ^ "A Beautiful Mind". Salon Magazine. 2001-12-21. Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for December 21–25, 2001". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2008-05-22.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for January 4–6, 2002". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2008-05-22.

- ^ "A Beautiful Mind (2001)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- ^ "74th Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on August 24, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ^ "A Beautiful Mind (2001) - Awards and Nominations". Yahoo! Movies. Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ^ "AFI Awards 2001". American Film Institute. Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ^ "AFI Awards 2001: Movies of the Year". American Film Institute. Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ^ "A Beautiful Mind (2001)". movies.com. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

^London Academy of Media Film & Tv,Russel Crowe

Additional reading

- Akiva Goldsman. A Beautiful Mind: Screenplay and Introduction. New York, New York: Newmarket Press, 2002. ISBN 1-55704-526-7

External links

- 2001 films

- 2000s drama films

- American biographical films

- American drama films

- Best Drama Picture Golden Globe winners

- Best Picture Academy Award winners

- English-language films

- Fictional portrayals of schizophrenia

- Films about psychiatry

- Films based on actual events

- Films based on biographies

- Films featuring a Best Drama Actor Golden Globe winning performance

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actress Academy Award winning performance

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actress Golden Globe winning performance

- Films shot in New Jersey

- Films set in New Jersey

- Films set in Massachusetts

- Films set in the 1940s

- Films set in the 1950s

- Films set in the 1960s

- Films set in the 1970s

- Films set in the 1990s

- Films whose director won the Best Director Academy Award

- Films whose writer won the Best Adapted Screenplay Academy Award

- Films about mathematics

- Films directed by Ron Howard

- Universal Pictures films

- DreamWorks films

- Imagine Entertainment films