Jamal al-Din al-Afghani: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 469543079 by 183.83.239.45 (talk) |

Fixed links to Encyclopædia Iranica articles & General fixes using AWB (7910) |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Sayyid Muḥammad ibn Ṣafdar Husaynī''' ({{lang-fa| سید محمد بن صفدر حسینی }}), better known as '''Sayyid Jamāl-ad-Dīn al-Afghānī'''<ref name="Britannica">{{cite web |url=http://www.britannica.com/ebc/article-9368411 |title=Jamāl ad-Dīn al-Afghānī |accessdate=2010-09-05 |work=Elie Kedourie |publisher=The Online [[Encyclopædia Britannica]] |date=}}</ref><ref name="Iranica">{{cite web |url=http://www. |

'''Sayyid Muḥammad ibn Ṣafdar Husaynī''' ({{lang-fa| سید محمد بن صفدر حسینی }}), better known as '''Sayyid Jamāl-ad-Dīn al-Afghānī'''<ref name="Britannica">{{cite web |url=http://www.britannica.com/ebc/article-9368411 |title=Jamāl ad-Dīn al-Afghānī |accessdate=2010-09-05 |work=Elie Kedourie |publisher=The Online [[Encyclopædia Britannica]] |date=}}</ref><ref name="Iranica">{{cite web |url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/afgani-jamal-al-din |title=Afghani, Jamal-ad-Din |accessdate=2010-09-05 |work=N.R. Keddie |publisher=[[Encyclopædia Iranica]] |date=December 15, 1983}}</ref><ref name="Oxford">{{cite web |url=http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/article/opr/t243/e8?_hi=5&_pos=1 |title=Afghani, Jamal ad-Din al- |accessdate=2010-09-05 |work=[[Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies]] |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |date=}}</ref><ref name="JVL"/> ({{lang-fa|سید جمالالدین افغانی}}) and '''Sayyid Jamal-ad-Din Asadabadi''' ({{lang-fa|سید جمالالدین اسدآبادی}}), (b. 1838, d. March 9, 1897), was a [[politics|political]] [[activism|activist]] and [[Islamic]] [[ideology|ideologist]] in the [[Muslim world]] during the late 19th century, particularly in the [[Middle East]], [[South Asia]] and [[Europe]]. One of the founders of Islamic modernism<ref name="JVL">{{cite web |url=https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/Afghani.html |title=Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani |accessdate=2010-09-05 |work= |publisher=[[Jewish Virtual Library]] |date=}}</ref><ref name="CIS">{{cite web |url=http://www.cis-ca.org/voices/a/afghni.htm |title=Sayyid Jamal ad-Din Muhammad b. Safdar al-Afghani (1838–1897) |accessdate=2010-09-05 |work=[[Saudi Aramco World]] |publisher=Center for Islam and Science |year=2002}}</ref> and an advocate of [[pan-Islamic]] unity,<ref>Ludwig W. Adamec, ''Historical Dictionary of Islam'' (Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 2001), p. 32</ref> he has been described as "less interested in theology than he was in organizing a [[Muslim]] response to [[Western world|Western]] pressure."<ref>[[Vali Nasr]], ''The Shia Revival: How Conflicts within Islam Will Shape the Future'' (New York: Norton, 2006), p. 103.</ref> |

||

== Early life and origin == |

== Early life and origin == |

||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Commons category|Jamal-ad-Din al-Afghani}} |

{{Commons category|Jamal-ad-Din al-Afghani}} |

||

*[http://www. |

*[http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/afgani-jamal-al-din Jamal-ad-Din Afghani], a comprehensive article in Encyclopædia Iranica. |

||

*[http://www.cis-ca.org/voices/a/afghni.htm Sayyid Jamal ad-Din Muhammad b. Safdar al-Afghani (1838–1897)], a complete biography. |

*[http://www.cis-ca.org/voices/a/afghni.htm Sayyid Jamal ad-Din Muhammad b. Safdar al-Afghani (1838–1897)], a complete biography. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Persondata <!-- Metadata: see [[Wikipedia:Persondata]]. --> |

{{Persondata <!-- Metadata: see [[Wikipedia:Persondata]]. --> |

||

| Line 80: | Line 82: | ||

| PLACE OF DEATH = [[Istanbul]], [[Ottoman Empire]] |

| PLACE OF DEATH = [[Istanbul]], [[Ottoman Empire]] |

||

}} |

}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Al-Afghani, Jamal ad-Din}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Al-Afghani, Jamal ad-Din}} |

||

[[Category:Al-Nahda]] |

[[Category:Al-Nahda]] |

||

Revision as of 22:23, 15 January 2012

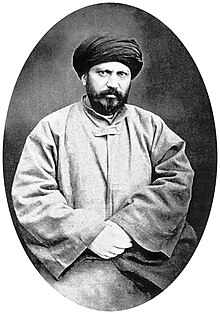

Jamal-ad-Din Asadabadi (al-Afghani) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal | |

| Born | 19 June 1838 |

| Died | September 1, 1897 (aged 59) |

| Religion | Islam, Shia |

Sayyid Muḥammad ibn Ṣafdar Husaynī (Persian: سید محمد بن صفدر حسینی), better known as Sayyid Jamāl-ad-Dīn al-Afghānī[1][2][3][4] (Persian: سید جمالالدین افغانی) and Sayyid Jamal-ad-Din Asadabadi (Persian: سید جمالالدین اسدآبادی), (b. 1838, d. March 9, 1897), was a political activist and Islamic ideologist in the Muslim world during the late 19th century, particularly in the Middle East, South Asia and Europe. One of the founders of Islamic modernism[4][5] and an advocate of pan-Islamic unity,[6] he has been described as "less interested in theology than he was in organizing a Muslim response to Western pressure."[7]

Early life and origin

He claimed to be of Afghan origin most of his life but evidence suggests that he was born in Iran.[3][8] Although some older sources claim that Asadabadi was born in a district of Kunar Province in Afghanistan which is also called Asadabad,[9][10] overwhelming documentation (especially a collection of papers left in Iran upon his expulsion in 1891) now proves that he was born in Iran, in the village of Asadābād, near the city of Hamadān into a family of Sayyids.[1][2][8] Records indicate that he spent his childhood in Iran and was brought up as a Shi'a Muslim.[1][2] According to evidence reviewed by Nikki Keddie, he was educated first at home then taken by his father for further education to Qazvin, to Tehran, and finally, while he was still a youth, to the Shi'a shrine cities in Iraq.[8] It is thought that followers of Shia revivalist Shaikh Ahmad Ahsa'i had an influence on him.[11] An ethnic Persian, al-Afghani claimed to be an Afghan in order to present himself as a Sunni Muslim[11][12] and escape oppression by the Iranian ruler Nāṣer ud-Dīn Shāh.[2] One of his main rivals, the sheikh Abū l-Hudā, called him Mutaʾafghin ("the one who claims to be Afghan") and tried to expose his Shi'a roots.[13] Other names adopted by al-Afghani were al-Kābulī ("[the one] from Kabul") and al-Istānbulī ("[the one] from Istanbul"). Especially in his writings published in Afghanistan, he also used the pseudonym ar-Rūmī ("the Roman" or "the Anatolian").[8]

Political activism

At the age of 17 or 18 in 1855–56, Asadabadi travelled to British India and spent a number of years there studying religions. In 1859, a British spy reported that Asadabadi was a possible Russian agent. The British representatives reported that he wore traditional cloths of Noghai Turks in Central Asia and spoke Persian, Arabic and Turkish language fluently.[14] After this first Indian tour, he decided to perform Hajj or pilgrimage at Mecca. His first documents are dated from Autumn of 1865, where he mentions leaving the "revered place" (makān-i musharraf) and arriving in Tehran around mid-December of the same year. In the spring of 1866 he left Iran for Afghanistan, passing through Mashad and Herat.

After the Indian stay, all sources have Afghānī next take a leisurely trip to Mecca, stopping at several points along the way. Both the standard biography and Lutfallāh's account take Afghānī's word that he entered Afghan government service before 1863, but since document from Afghanistan show that he arrived there only in 1866, we are left with several years unaccounted for. The most probably supposition seems to be that he may spent longer in India than he later said, and that after going to Mecca he travelled elsewhere in the Ottoman Empire. When he arrived in Afghanistan in 1866 he claimed to be from Istanbul, and he might not have made this claim if he had never even seen the city, and could be caught in ignorance of it.[15]

— Nikki R. Keddie, 1983

He was spotted in Afghanistan in 1866 and spent time in Qandahar, Ghazni, and Kabul.[1] He became a counsellor to the King Dost Mohammad Khan and later to Mohammad Azam. At that time he encouraged the king to oppose the British but turn to the Russians. However, he did not encourage Mohammad Azam to any reformist ideologies that later were attributed to al-Afghani. Reports from the colonial British Indian and Afghan government stated that he was a stranger in Afghanistan, and spoke the Persian language with Iranian accent and followed European lifestyle more than that of Muslims, not observing Ramadan or other Muslim rites.[14] In 1868, the throne of Kabul was occupied by Sher Ali Khan, and Asadabadi was forced to leave the country.[2]

He travelled to Istanbul, passing through Cairo on his way there. He stayed in Cairo long enough to meet a young student who would become a devoted disciple of his, Muhammad 'Abduh.[16]

In 1871, al-Afghani moved to Egypt and began preaching his ideas of political reform. His ideas were considered radical, and he was exiled in 1879. He then travelled to different European and non-European cities: Istanbul, London, Paris, Moscow, St. Petersburg and Munich.

In 1884, he began publishing an Arabic newspaper in Paris entitled al-Urwah al-Wuthqa ("The Indissoluble Link"[1]) with Muhammad Abduh. The newspaper called for a return to the original principles and ideals of Islam, and for greater unity among Islamic peoples. He argued that this would allow the Islamic community to regain its former strength against European powers.[citation needed]

Asadabadi was invited by Shah Nasser ad-Din to come to Iran and advise on affairs of government, but fell from favour quite quickly and had to take sanctuary in a shrine near Tehran. After seven months of preaching to admirers from the shrine, he was arrested in 1891, transported to the border with Ottoman Mesopotamia, and evicted from Iran. Although Asadabadi quarrelled with most of his patrons, it is said he "reserved his strongest hatred for the Shah," whom he accused of weakening Islam by granting concessions to Europeans and squandering the money earned thereby. His agitation against the Shah is thought to have been one of the "fountain-heads" of the successful 1891 protest against the granting a tobacco monopoly to a British company, and the later 1905 Constitutional Revolution.[17]

Political and religious views

Asadabadi's ideology has been described as a welding of "traditional" religious antipathy toward non-Muslims "to a modern critique of Western imperialism and an appeal for the unity of Islam", urging the adoption of Western sciences and institutions that might strengthen Islam.[12]

Although called a liberal by the contemporary English admirer, Wilfrid Scawen Blunt,[18] Jamal ad-Din did not advocate constitutional government. In the volumes of the newspaper he published in Paris, "there is no word in the paper's theoretical articles favoring political democracy or parliamentarianism," according to his biographer. Jamal ad-Din simply envisioned "the overthrow of individual rulers who were lax or subservient to foreigners, and their replacement by strong and patriotic men."[19]

According to another source Asadabadi was greatly disappointed by the failure of the Indian Mutiny and came to three principal conclusions from it:

- that European imperialism, having conquered India, now threatened the Middle East

- that Asia, including the Middle East, could prevent the onslaught of Western powers only by immediately adopting the modern technology of the West

- and that Islam, despite its traditionalism, was an effective creed for mobilizing the public against the imperialists.[20]

He believed that Islam and its revealed law were compatible with rationality and, thus, Muslims could become politically unified while still maintaining their faith based on a religious social morality. These beliefs had a profound effect on Muhammad Abduh, who went on to expand on the notion of using rationality in the human relations aspect of Islam (mu'amalat) .[21]

In 1881 he published a collection of polemics titled Al-Radd 'ala al-Dahriyyi (Refutation of the Materialists), agitating for pan-Islamic unity against Western Imperialism. It included one of the earliest pieces of Islamic thought arguing against Darwin's then-recent On the Origin of Species; however, his arguments incorrectly caricatured evolution, provoking criticism that he had not read Darwin's writings.[22] In his later work Khatirat Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani (The Ideas of al-Afghani), he accepted the validity of evolution, asserting that the Islamic world had already known and used it. Although he accepted abiogenesis and the evolution of animals, he rejected the theory that the human species is the product of evolution, arguing that humans have souls.[23]

Among the reasons why Asadabadi thought to have had a less than deep religious faith[who?] was his lack of interest in finding theologically common ground between Shia and Sunni (despite the fact that he was very interested in political unity between the two groups),[24] and his failure to marry. He is said to have "picked up female companionship when he wanted it without any show of religious scruples.", probably practising the temporary marriage (nikah al-mut'a) that only Shia communities recognize as licit (halal).[25]

It is a surprising information that Hanna Abi Rashid, then chief of the masonic lodge in Beirut, wrote in the book "Da’irat al-ma’arif al-Masoniyya" that “Jamal ad-Din Afghani was the chief of the masonic lodge in Egypt, which had about three hundred members, mostly scholars and state officials." [26]

Death and legacy

Jamal ad-Din Asadabadi died on March 9, 1897 in Istanbul and was buried there. In late 1944, due to the request of the Afghan government, his remains were taken to Afghanistan and laid in Kabul inside the Kabul University, a mausoleum was erected for him there. In Tehran, the capital of Iran, there is a square named after him (Asad Abadi Square).

References

- ^ a b c d e "Jamāl ad-Dīn al-Afghānī". Elie Kedourie. The Online Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ^ a b c d e "Afghani, Jamal-ad-Din". N.R. Keddie. Encyclopædia Iranica. December 15, 1983. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ^ a b "Afghani, Jamal ad-Din al-". Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ^ a b "Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ^ "Sayyid Jamal ad-Din Muhammad b. Safdar al-Afghani (1838–1897)". Saudi Aramco World. Center for Islam and Science. 2002. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ^ Ludwig W. Adamec, Historical Dictionary of Islam (Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 2001), p. 32

- ^ Vali Nasr, The Shia Revival: How Conflicts within Islam Will Shape the Future (New York: Norton, 2006), p. 103.

- ^ a b c d Keddie, Nikki R (1983). An Islamic response to imperialism: political and religious writings of Sayyid Jamāl ad-Dīn "al-Afghānī". United States: University of California Press. p. 4. ISBN 0520047745, 9780520047747. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ From Reform to Revolution, Louay Safi, Intellectual Discourse 1995, Vol. 3, No. 1 LINK

- ^ Historia, Le vent de la révolte souffle au Caire, Baudouin Eschapasse, LINK

- ^ a b Edward Mortimer, Faith and Power, Vintage, (1982)p.110

- ^ a b Arab awakening and Islamic revival By Martin S. Kramer

- ^ A. Hourani: Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age 1798–1939. London, Oxford University Press, p. 103–129 (108)

- ^ a b Molefi K. Asante, Culture and customs of Egypt, Published by Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, ISBN 0313317402, 9780313317408, Page 137

- ^ Keddie, Nikki R (1983). An Islamic response to imperialism: political and religious writings of Sayyid Jamāl ad-Dīn "al-Afghānī". United States: University of California Press. p. 212. ISBN 0520047745, 9780520047747. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Albert Hourani, Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age (Cambridge: Cambride UP, 1983), pp. 131–2

- ^ Roy Mottahedeh, The Mantle of the Prophet: Religion and Politics in Iran (Oxford: One World, 2000), pp. 183–4

- ^ Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, Secret History of the English Occupation of Egypt (London: Unwin, 1907), p. 100.

- ^ Nikki R. Keddie, Sayyid Jamal ad-Din “al-Afghani”: A Political Biography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972), pp. 225–26.

- ^ Ervand Abrahamian, Iran Between Two Revolutions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), pp. 62–3

- ^ Albert Hourani, Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age (Cambridge: Cambride UP, 1983), pp. 104–125

- ^ The Comparative Reception of Darwinism, edited by Thomas Glick, ISBN 0226299775

- ^ The Comparative Reception of Darwinism, edited by Thomas Glick, ISBN 0226299775

- ^ Nasr, The Shia Revival, p.103

- ^ Mottahedeh, The Mantle of the Prophet, p. 184

- ^ Abi Rashid, Hanna, Da’irat al-ma’arif al-Masoniyya (Beirut: 1961), p. 197.

In late 1944, due to the request of the Afghan government, his remains were taken to Afghanistan by Abdul Rahmon Popal and laid in Kabul inside the Kabul University

Further reading

- Bashiri, Iraj, Bashiri Working Papers on Central Asia and Iran, 2000.

- Black, Antony (2001). The History of Islamic Political Thought. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-93243-2.

- Cleveland, William (2004). A History of the Modern Middle East. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-4048-9.

- Keddie, Nikki Ragozin. Sayyid Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani: A Political biography. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972. ISBN 978-0520019867

- Watt, William Montgomery (1985). Islamic Philosophy and Theology. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-0749-8.

- Mehrdad Kia, Pan-Islamism in Late Nineteenth-Century Iran, Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 30–52 (1996).

External links

- Jamal-ad-Din Afghani, a comprehensive article in Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Sayyid Jamal ad-Din Muhammad b. Safdar al-Afghani (1838–1897), a complete biography.